Chapter 12

Achieving Everyday Operational Excellence

In This Chapter

![]() Recognising the importance of training

Recognising the importance of training

![]() Identifying areas for improvement

Identifying areas for improvement

![]() Staying the course and keeping focused

Staying the course and keeping focused

For everyday operational excellence to become a reality, managers and team leaders need to run their processes and activities effectively and efficiently. As Chapter 3 explains, these managers and leaders need to understand that their role is to work on their processes with the people in the processes to find ways of continuously improving performance. This chapter covers ensuring that people receive appropriate training, spotting improvement opportunities that benefit the organisation and give employees the chance to develop and master new skills, and keeping everyone on track for the long haul.

Deploying Lean Six Sigma Training

The people in the process need to feel that they’re able to challenge and improve the process and the way they work. To do so, they need to be engaged and empowered.

If people are to feel empowered, they need to feel that they’re being developed, and for that to happen the organisation must develop training plans. The primary focus in this chapter is on training people to develop Lean Six Sigma skills.

Hand in glove with the training and the training plan is the need to identify relevant projects. Such projects should be bite-sized and link to improvements to achieve strategy deployment. The projects need to tackle the right work and do the work in the right way. Not all improvement actions supporting strategy deployment will be DMAIC or DMADV projects (see Chapter 1). The operational areas, in particular, will need to adopt the Lean Six Sigma tools, techniques and principles in their day-to-day work too.

In many ways the key to creating a culture of continuous improvement hinges on how well managers understand the need to manage their processes and achieve everyday operational excellence. We look at the implications and requirements of that in the ‘Establishing How You Do Things’ section later in this chapter. For the moment, the focus is on training the belts.

Training the belts

The different levels of training in Lean Six Sigma are often referred to in terms of the coloured belts acquired in martial arts. Think about the qualities of martial arts Black Belts – highly trained, experienced, disciplined, decisive, controlled and responsive – and you can see how well this metaphor translates into the world of making change happen in organisations. Thankfully, you won’t be required to break bricks in half with your bare hands!

Yellow Belts

Some organisations develop a pool of Yellow Belts, who typically receive two days of practical training to a basic level on the most commonly used tools in Lean Six Sigma projects. The content is usually a sub-set of the Green Belt programme referred to below.

Yellow Belts work either as project team members or carry out mini-projects themselves in their local work environment, usually under the guidance of a Black Belt.

Green Belts

Green Belts are trained on the basic tools and lead fairly straightforward projects. The extent of training varies somewhat. In the US, for example, training typically takes from between five to ten days. In the UK some organisations break the training along the following lines: Foundation Green Belt level (four to six days’ training) covers Lean tools, process mapping techniques and measurement, as well as a firm grounding in the DMAIC methodology and the basic set of statistical tools. Advanced Green Belts (an additional six days’ training) receive further instruction on more analytical statistical tools and start to use statistical software. This approach ensures the training is delivered ‘just in time’ since early projects can be relatively simple, often involving an assessment of how the work gets done and enabling the identification and elimination of non-value-added steps, without the need for detailed statistical analysis.

Green Belts typically devote the equivalent of about a day a week (20 per cent of their time) to Lean Six Sigma projects, usually mentored by a Black Belt. Given that Green Belts already have 100 per cent of their time taken up with current work activities, organisations need to look closely at where the day a week is going to come from: there are only so many hours in a day! The long-term success of Lean Six Sigma initiatives can be compromised if people aren’t given the time and space to work on their improvement projects.

Black Belts

An expert Lean Six Sigma practitioner is trained to Black Belt level, which means attending several modules of training over a period of months. Most Black Belt courses involve around 20 days of full-time training as well as working on projects in practice, under the guidance of a Master Black Belt. The role of the Black Belt is to lead complex projects and provide expert guidance on using the Lean Six Sigma tools and techniques to the project teams. Black Belts are often from different operational functions across the company, coming into the Black Belt role from customer service, finance, marketing or HR, for example. The Black Belt role is usually full time, often for a term of two to three years, after which the individuals return to operations. In effect, Black Belts become internal consultants working on improving how the organisation works by changing its systems and processes for the better.

Master Black Belts

The Master Black Belt, another full-time role, receives the highest level of training and becomes a full-time professional Lean Six Sigma expert. The Master Black Belt will have extensive project management experience and should be fully familiar with the importance of the soft skills needed to manage change. An experienced Master Black Belt is likely to want to take on this role as a long-term career path, becoming a trainer, coach or deployment advisor, and working with senior executives to ensure the overall Lean Six Sigma programme is aligned to the strategic direction of the business. Master Black Belts tend to move around from one major business to another after typically three or four years in one organisation. They’re likely to have been a Black Belt for at least two years before moving into this role.

Assessing the skills

Selecting the right candidates for training is clearly essential. In fact, some organisations undertake assessment centres to identify suitable people. But in many ways, assessing the skills of the newly-trained belts is more important. Certification (see the ‘Setting up certification’ section later in this chapter) is obviously one way of establishing an individual’s skill level. To some extent, you can also do so by using the framework created by Donald Kirkpatrick, a professor at the University of Wisconsin, and in particular, by reference to his levels two and three. Kirkpatrick’s approach to evaluating the effectiveness of training has become the benchmark within the training industry. He identified four levels:

- Reaction: The immediate response to the training event.

- Learning: The increase in knowledge as a result of the event.

- Behaviour: Changes in behaviour in the normal daily work environment as a result of the newly acquired knowledge.

- Results: The benefit to the business as a result of the reaction, learning and behaviour.

Examples of how these levels are applied are shown below:

- Level 1: The trainers ask delegates to assess the course, perhaps using net promoter score (NPS) forms (Chapter 13 explains NPS in full) at the end of each training programme or workshop. NPS is a world-class best practice method of obtaining customer feedback. The results can form part of an organisation’s balanced scorecard.

- Level 2: Delegates routinely sit (certification) exams after completing their training; in-company clients also often ask for the inclusion of specific tests and exams when delegates don’t proceed towards external certification.

- Level 3: Here, clients target specific changes in behaviour resulting from the training – some very formally, some informally. Observed changes in behaviour can be as simple as trained managers using the new Lean Six Sigma tools more routinely, avoiding jumping to solutions, undertaking post-project reviews, and so on. In cases where learning and development specialists look for and assess very specific behavioural changes, some organisations use psychometric profiling as a way of measuring them.

- Level 4: At this level, organisations explicitly measure the outcome of their improvement projects (and in aggregate at programme level).

Setting up certification

Many organisations utilise certification processes to ensure that a set standard is reached through exams and project assessments. Certification processes are established in many countries by bodies such as the British Quality Foundation (BQF) and the American Society of Quality (ASQ). Many large corporate businesses set up their own internal certification processes, with recognition given at high-profile company events to newly graduated belts.

Essentially, certification tends to be a three-part process. Complete the training, pass an exam (usually multi-choice for Yellow and Green Belt), and provide evidence of applying the tools in some way. This is often through the presentation of a project storyboard that walks through and explains the project from start to finish. The ASQ doesn’t offer Yellow Belt certification.

You can find full details of both the certification and body of knowledge requirements of the BQF and ASQ on their respective websites: www.bqf.org.uk and asq.org.

A new term has recently been used to describe people who have merely received an introduction to the topic – White Belt. No certification process is involved and these programmes vary in length from an hour or two through to a full day.

Prioritising and Selecting Improvement Opportunities

Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley) covers the selection of Lean Six Sigma projects and introduces a number of selection and prioritisation tools for practitioners to use. These include:

- The XY grid

- N/3

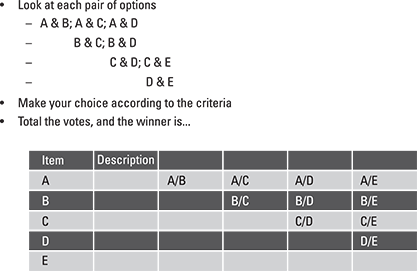

- Paired comparisons

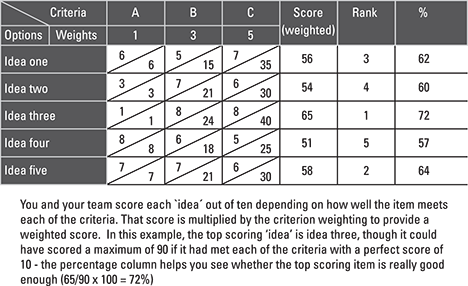

- Criteria- or priority-based matrix

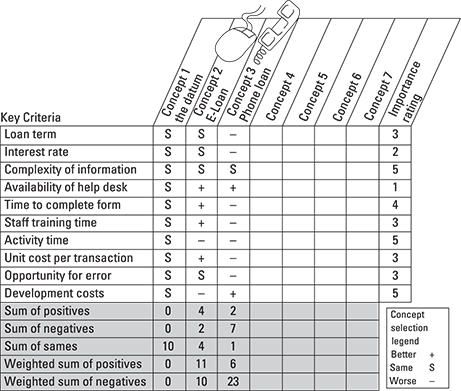

- Pugh matrix

You can find descriptions of each of these selection tools in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley), but the following diagrams provide at least an indication of how they can be used.

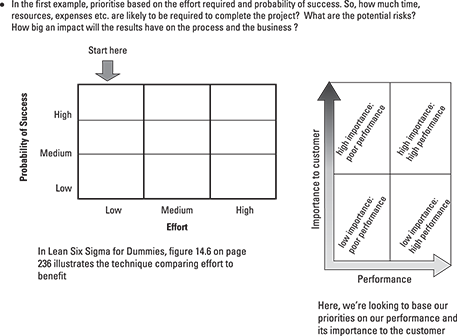

Figure 12-1 shows the XY grid, which is a simple format for making an initial assessment of priorities.

The N/3, shown in Figure 12-2, is a simple technique for making selections. We recommend using it to help reduce a lot of options to a more manageable number and then using paired comparisons to make a more objective selection.

Figure 12-1: Assessing priorities with the XY grid.

Figure 12-2: Voting using the N/3 process.

The paired comparisons technique (Figure 12-3) is often used to provide weightings to selection criteria and links neatly to the criteria- or priority-based matrix (Figure 12-4).

The criteria- or priority-based matrix can be used for a wide variety of selection issues, including suppliers following an invitation to tender, staff recruitment, or promotion, and even the next school you’d like to send your children to!

Figure 12-3: Forcing selection through paired comparisons.

Figure 12-4: Weighing things up with the criteria- or priority-based matrix.

The Pugh matrix, shown in Figure 12-5, is often used to compare competing concept designs. One design is chosen as the ‘datum concept’ that will provide a standard reference point. The other concepts are then compared with it to determine whether they’re better/easier, worse/harder or the same.

One additional selection tool that can be especially helpful in Kaizen rapid improvement workshops is the nominal group technique (NGT), which involves silent brainstorming and decision-making. NGT is a structured variation of small group discussion methods, and is ideal in rapid improvement events.

The process prevents the domination of discussion by a single person, encourages the more passive group members to participate, and results in a set of prioritised solutions or recommendations. NGT can thus be seen as an opportunity to secure buy-in and engagement.

Figure 12-5: Making a datum with the Pugh matrix.

NGT involves the following steps:

- Divide the people present into small groups of five or six, preferably seated around a table.

- Ask an open-ended question, for example: ‘What could we do to help reduce the set-up time for this process?’ or ‘How could we improve the on-time delivery of customer orders?’

- Instruct each member of the team to spend several minutes in silence individually brainstorming possible ideas.

- Ask each group to write their ideas on sticky notes and to put them on a flipchart.

- Work through the ideas, without judgement or criticism. Do encourage clarification in response to questions.

- Ask members to individually rank the solutions as first, second, third, fourth and so on. Add up the rankings each solution receives: the solution with the best total ranking is selected as the final decision.

In a way, some similarity exists between NGT and the simpler N/3 technique (refer to Figure 12-2) in that voting is involved in the process, but this time individuals are sequencing options in terms of their perceived priority.

Whichever selection techniques you use, the process must support strategy deployment. Clearly prioritised criteria always help to maintain appropriate focus.

Sometimes the improvement solution really is clear. Having described a problem in the Define phase of DMAIC, it may well be that by clarifying how the work gets done – perhaps by using process stapling – one or more non-value-adding steps can be seen. Making sure that no unintended consequences may result, these steps could then simply be removed. Process stapling is described in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley). It’s one way to really understand a process and its related chain of events. Very simply, process stapling means taking a customer order, for example, and literally walking it through the entire process, step-by-step, as though you were the order.

No matter where the order goes, you go too. By following the order you start to see what really happens, who does what and why, and how, where and when they do it. Process stapling is an ideal first step in mapping out a process.

Rapid improvement events

Kaizen (pronounced Kai Zen) means change for the better. It’s often associated with short, rapid, incremental improvement and forms a natural part of an organisation’s approach to continuous improvement.

Kai Sigma is developed from the Kaizen approach and adapts the framework of the DMAIC phases in a series of facilitated workshops. The facilitator doesn’t need to use the language of Lean or Six Sigma. Kai Sigma aims to involve the people in the process in making improvements to that process, and the approach makes use of team knowledge rather than detailed analysis. The solution may be known by the team, but historically they’ve not been listened to! Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley) provides more detail about Kai Sigma workshops and the importance of pre-event preparation.

DMAIC projects

Typically, Green Belt DMAIC projects are likely to run for three to four months, assuming the Green Belts are generally spending only 20 per cent of their time working on the problem. Black Belt projects may well take longer, even though the Black Belts are usually working full time in this role.

Yellow Belts tend to be members of improvement teams, but are perfectly able to pick up their own, albeit very focused, projects. These are typically tackling local operational issues, for example helping their team establish more effective visual management or taking part in process stapling, described earlier in this chapter.

Check out Chapter 1 for more on DMAIC projects.

Applying manufacturing process improvements to services

One of the most interesting observations we’ve made in comparatively recent years is the realisation on the part of manufacturing organisations that Lean Six Sigma can be applied to their back office and transactional processes.

On the shop floor, many manufacturers have already seen the success that can result from the deployment of Lean Six Sigma. But they’ve never considered whether the process could work outside of manufacturing. It’s probably fair to say that many of our clients are service and public sector organisations.

Recognising that the tools of Lean Six Sigma have as much relevance in service as in manufacturing has always seemed harder for organisations to accept. The difficulty, perhaps, is that service products and office applications may not appear either so physical or so visual. Because manufacturing always involves tangible products, waste/scrap is so much easier to spot, especially when it’s in a skip in the back yard.

In terms of training, there tends to be more awareness of the need for statistical analysis in a manufacturing environment, especially where precise engineering specifications are involved. That said, techniques such as statistical process control (SPC), are hugely relevant in the service arena, where measurement systems are generally not as refined as in manufacturing. Raising awareness of the need for more statistical analysis in the service sector is likely to take some considerable time. Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley) provides more detail about statistical control and SPC in the Office by Mal Owen and John Morgan (Greenfield Publishing) contains a wide range of service applications using control charts.

When we work with manufacturing clients, Yellow Belt training typically takes three days rather than the two needed in a service company. Also, the manufacturing organisation is more likely to train its Black Belts in DMADV, though, again, this may be down to historical misunderstandings about the potential of the design and innovation method in service organisations. Arguably, since errors in many service processes occur in front of the customer, a greater need for the analysis and prevention of defects exists in the service/government/healthcare sectors, and with it the need for better-designed processes.

The organisation’s executive team realised that the company needed to differentiate itself in the eyes of its customers, the Independent Financial Advisers (IFAs) who sell and, to some degree, service policies for the end customer. The company wanted to establish itself as the natural choice for IFAs or, at least, a targeted segment of them. Superior service and the ability to demonstrate value were key elements of the strategy. Current performance indicated that it was some way from this ideal situation, with considerable variation in the processing of new business applications, especially those requiring medical evidence from a GP or specialist.

The time taken to issue policies ranged from between a couple of days to a couple of months, and approximately 10 per cent of all policy applications had to be reworked, either due to errors or missing information. Without significant improvement, little prospect existed of their strategy being achieved.

The leadership team believed that its business could benefit from Lean Six Sigma. It needed to show how, with each step in the new business process, value is added to the work in progress, just as a car on the production line gets doors or parts added to it as it flows down the assembly line.

A number of Lean Six Sigma tools were applied to enable the work to flow – none involved rocket science, simply a little time and the involvement of people:

- The current state picture for the end-to end-process was developed starting with a high level view of the process and followed by process stapling and process mapping. The exercise involved a mix of people from the process together with a Green Belt, and the outcomes were discussed by the team with management. The exercise highlighted many improvement opportunities.

- Linked processes in the end-to-end process were placed near to one another. Work had been organised by function in separate departments and teams, which created a silo effect and delays in transferring applications to other areas that performed different functions. Delays were compounded as the work was also processed in batches. The functional silos were eliminated, helping facilitate a move from batches to single piece flow.

- Processes and procedures were standardised, and techniques such as visual management and daily team meetings were used to support the overall aims. As a simple example, prior to the application of Lean concepts, people had been allowed to choose their own system for storing files. This meant that new or temporary staff had difficulty finding files that had been stored in various different ways, such as by policy number, by date received, or alphabetically. The new system required files to be stored alphabetically and in the same clearly labeled cabinet at each work area.

- Some processes involved returning work to a previous step for further processing. This system caused confusion, disrupted flow and resulted in waiting time in some steps. The process was changed to avoid the need for such to-ing and fro-ing.

- The work flow was further smoothed by applying the concept of takt time. Takt time tells you how quickly you need to action things in relation to customer demand, given the number of available hours in the working day or shift. Takt time is explained in more detail in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley). The business established a takt time of five minutes per application or 12 applications per hour, encouraging and empowering employees to make process improvements to reduce the cycle time needed in order to meet the takt time required. Continuous improvement meant the ‘one best way’ was updated regularly.

- Workloads were balanced where possible, ensuring the work was evenly and sequentially distributed. The previous approach, whereby new applications were allocated alphabetically, was replaced by a ‘date received’ allocation so that every team received the same number of applications. This approach reduced unnecessary delays in the system and meant customers were being dealt with in an appropriate time sequence.

- Tasks were separated into categories based on their level of difficulty and the processing skills needed. For example, two categories were developed for applications, whereby one handled cases needing medical evidence and the other handled less time-consuming cases that didn’t require GP reports.

- Visual management came into play in the form of performance data displayed on white boards for everyone to see. Where practical, the information was updated by the team members. The boards became the locations for the daily team meetings where work levels and improvement ideas were discussed.

These actions led to enhanced performance and increased employee and customer satisfaction. Turnaround times for policies issued were reduced by 65 per cent for medical cases and 80 per cent for non-medical applications. Rework fell from 10 per cent to just over 1 per cent.

Ongoing, the organisation made further changes by segmenting its IFA customers into different categories and creating customer-facing teams dealing with new business through to claims. This ‘cradle to grave’ set-up helped to make further improvements in both employee and customer satisfaction, leading to increased market share, and though its creation involved a significant investment in training time, process costs were similarly reduced.

Establishing How You Do Things

Everyday operational excellence is all about doing things well each and every day and creating a culture of continuous improvement. And it begins by understanding how the work gets done and how well – just like in the example in the previous section. Essentially, the tools and techniques used in the Measure phase of a DMAIC project can help you understand the current situation.

Understanding the value stream

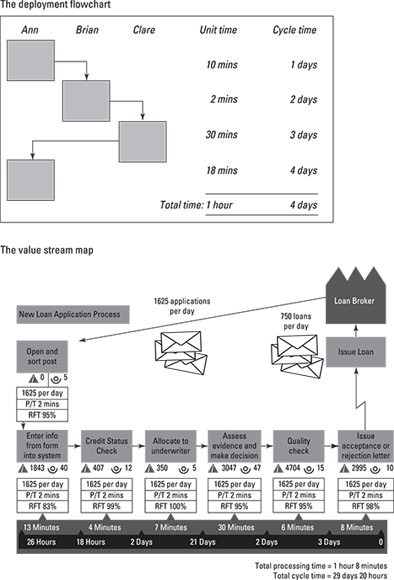

Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley) looks at developing either a deployment flowchart or value stream map. Both provide effective pictures of how the work gets done.

Figure 12-6: Developing a picture of how the work gets done.

In both these examples, you can see how the addition of data has highlighted opportunities for improvement. So, not only do the pictures show how the work gets done, they also provide a framework for measures to help understand how well it gets done.

As you come to understand the current situation and spot the opportunities for improvement, you need to decide whether these are ‘just do it’ activities, Kaizen/Kai Sigma rapid improvement workshops, or more formal DMAIC or DMADV projects. Often these are decisions that can be made at the daily team meeting, or referred from there through the organisation’s governance system.

Using Kaizen effectively

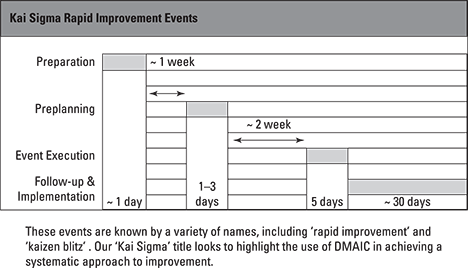

A typical outline Kaizen event plan is presented in Figure 12-7.

Figure 12-7: Preparation and planning are essential ingredients for successful events.

Essentially, you need to identify what it is you’re going to tackle, for example the key wastes in the current state that need to be removed in order to achieve the future state of how you would like the process to operate. These might already have been highlighted on a process or value stream map. For example, the wastes may relate to:

- Steps with high correction rates

- Steps with long processing times

- Excessive delays between steps

- Excessive checking

- Steps with high inventory or work in progress

To ensure that the event is a success, some planning and pre-work is needed. Where appropriate, look to see if data is available or whether you need to collect some in advance of the event. You may well find yourself being asked to facilitate workshop sessions or specific activities, so it’s worth considering the need for facilitation skills.

The role of the facilitator is to ensure that Kaizen/Kai Sigma rapid improvement events, meetings, and interactions between people are effective and productive. Making best use of the skills and contributions from everyone involved is vital. The facilitator needs to make sure that all aspects of the event are orchestrated to ensure success and to consider it in three phases: preparation, the event process itself, and the event and meeting follow up.

Preparation

Some of the key things that need to be considered in preparation for the event include:

- Purpose and agenda: Does the event have a clear purpose? Is everyone who is attending the event clear about that purpose? Has an agenda been drawn up, which is structured to ensure that the purpose is achieved? In terms of authority, is everyone clear about what they can and cannot do?

- Attendees: Based on the purpose and agenda, are you clear about who needs to attend? If critical inputs need to be made, who is going to make them? Do you need people at the event because they may have relevant background knowledge that will add to the quality of the discussion? Everyone attending should be there for a reason, and they should be clear about expectations for their contribution.

- Event dynamics: Knowing the purpose, agenda and attendees, you can probably predict in advance potential areas of difficulty. Are people attending who have very strong views and may be in conflict? Must difficult issues be discussed? Are people attending the event who just don’t get along? Either way, stakeholder analysis can be very useful here (see Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley) for details). It may well lead you to identify key influencers that need some pre-positioning beforehand to make sure that they come to the session in the right frame of mind. If you can identify these potential difficulties up front you can structure the agenda and the event process to help address these issues and minimise any negative impact on the proceedings.

- Event structure: With an outline agenda, knowledge of how much time you have available and awareness of the likely event dynamics, you need to consider how to allocate time across the different agenda items; where to place emphasis; and how much time to allocate to inputs, discussion, and decision-making. In setting the event structure you also need to take account of the need for breaks at various points (coffee, lunch, tea), and to be aware of how these breaks will impact the flow of the discussion. For long events, you also need to think about how to keep people engaged throughout the day, for example structuring the event so that people have something interesting to do after lunch.

- Event roles: Typically, the event will have a champion or sponsor who helps establish the purpose of and objective for the event. They’ll also clarify the authority the team has been given.

The role of the facilitator is clearly different. As part of the preparation, the champion/sponsor and facilitator need to agree their different roles and the overall purpose and plan for the event. Someone within the team should be appointed timekeeper during the event to keep an eye on the clock and the progress being made. Another team member should be given responsibility for taking notes, capturing information and the decisions made.

- Event venue: A key part of a successful event is the venue. Consider what sort of environment you want to create for the outcome you want to achieve. People’s behaviour during the event is likely to reflect the surroundings and environment they’re in, so you might want to make sure everything is clean and tidy beforehand. Decide whether the event will be on- or off-site. If the former, think about how you can avoid attendees being distracted by operational demands that might cause them to leave the event.

Consider room layout in terms of its size and formality (or otherwise). You may need break-out rooms to work on specific issues. Equipment is another important issue. You’ll need a number of things in the room. The toolkit is likely to include a flipchart and stand, paper and spare flipchart pads, pens, brown paper, sticky putty and sticky notes. You might also need tape measures, stop watches, a digital camera and possibly a video camera, batteries (just in case), a laptop and a projector. Much will depend on the purpose of the event and whether during the day you intend to be monitoring and measuring the process activity as it happens.

The event process

The role of the facilitator is to ensure that the overall process is orchestrated and runs to time. With good preparation you’ll be clear about the outline process you want to take people through. Of course, you’ll need to be flexible and respond appropriately as the dynamics dictate, but your pre-work gives you a good framework.

Event and meeting follow up

At the end of the event, or shortly afterwards, the facilitator and the champion review the event to note what went well, what could have been improved, whether objectives were met, and the follow up required. This review will help in preparing for the next session. Where appropriate, the facilitator needs to make sure that actions and next steps from the event are circulated as quickly as possible.

Once the improvement solution has been implemented, an effective handover must take place and a control plan agreed.

Achieving results

Improvements naturally flow from the use of the Lean Six Sigma tools and approach, and the evolving culture of continuous improvement. Holding the gains is often the more difficult task.

The control plan is an essential ingredient of everyday operational excellence, and is described in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley). As part of the control plan, you need to deploy a ‘one best way’ of doing things, a ‘standard work’ approach, but you also have to recognise that, in an evolving culture of continuous improvement, the one best way will change with further improvement activity. All of this standardisation should be coupled with effective visual management to help ensure not only that everyone knows what’s happening, but also to create a safer working environment and make it easier to find things.

Keeping the focus

No matter how good the initial improvement results are, it’s crucial that everyone recognises that Lean Six Sigma thinking isn’t simply a case of applying some tools and techniques to solving a problem. You need to adopt the concepts, and the thinking and behaviours that accompany them, to hold the gains and create new ones in an environment that really is pursuing perfection en route to your True North.

Organisations tend to get what they measure, so it’s vital to ensure that the right things are being measured and the right behaviours encouraged and recognised.

Giving Power to the People

Everyone involved in a transformation process will find it challenging at some point. You need to ensure that people receive appropriate training, are able to express doubts and concerns and, most importantly, feel that everyone’s in it together and knows where they’re going. They also need the proper resources and infrastructure to support the change process.

Recognising the challenge management faces

Chapter 3 identifies the need for managers to work on their processes with the people in the processes to find ways of continuously improving the performance of those processes. For many managers, that in itself is a significant challenge.

The majority of managers will probably need training in everyday operational excellence. Our three-day everyday operational excellence training programme covers a sub-set of the Lean Six Sigma tools taught at Yellow and Foundation Green Belt levels. But these are the tools that need to be applied to daily activities and not just improvement projects. Used in this way, these tools enable processes to be owned as well as effectively and efficiently managed, leading to stable processes, whereby:

- A clear customer-focused objective exists, together with prioritised customer requirements. In other words, measureable CTQs have been identified.

- Appropriate process maps are in place. These will involve at least a SIPOC (Suppliers, Inputs, Process, Outputs, Customers) diagram and a deployment flowchart or value stream map; perhaps both.

- A balance of input, in-process and output measures exists. That is, an effective data collection process is in place. The vital few Xs and Ys are being measured and the correlation between these variables is understood and managed.

- The process is stable and in statistical control. Control charts are part of visual management, helping to ensure that variation is understood. Where special causes are present, improvement activity is underway and is picked up at the daily team meeting, if not before.

- The process meets the CTQs. Performance in meeting CTQs is monitored and understood and improvement activity is underway where the CTQs are not being met. Progress is picked up as part of the daily team meeting.

- The process has been error-proofed. Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) has been carried out, prevention has been built in where possible and the identification of new error-proofing opportunities forms part of the daily team meeting.

Refer to Chapter 2, or see Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley), for more on FMEA.

- A control plan is in place that clearly identifies what to do if things go wrong. An example is a situation in which ongoing data indicates a warning in some way.

The training and ongoing application of the learning also serves to begin the process of introducing a common language of Lean Six Sigma tools, techniques and principles. In turn, this supports the ongoing identification of improvement opportunities that can be actioned either by managers and their teams or through more formal DMAIC or DMADV projects. Each DMAIC or DMADV project should have a champion.

Managers and leaders have their own set of challenges to deal with. In fact, generating a list of the challenges facing champions and their teams is easy. The ‘top ten’ list below reflects many of the common problems experienced in organisations:

- Ineffective improvement charters that are too vague or too large.

- Team members not sharing a unified direction or vision.

- Teams with the wrong mix of skills or functional representation.

- Champions, team members or leaders not spending enough time on the projects.

- Pressure for immediate financial impact leading to inappropriate shortcuts that frustrate team members and discredit the systematic approach being promoted.

- Other key stakeholders not being fully supportive of the project or the team’s approach.

- Inadequate budget to complete the project or implement recommended solutions.

- Competing or conflicting project objectives among different improvement teams, leading to confusion.

- The project scope keeps getting bigger.

- Poorly managed handovers fail to integrate the improvements throughout the organisation.

Empowering teams

In owning and working on the process, you need to ensure it’s ‘managed’ – that you really are working on the process with the people in the process. You need to involve the relevant employees so that they feel able to challenge and help improve how the work gets done. They must feel engaged and their active involvement in the daily team brief is an essential element in securing that engagement. Agreeing ownership of different activities is one way to help increase people’s sense of participation.

You also need to make absolutely sure that the training and accreditation skills charts are up to date and that the scheduling of training and coaching is at an appropriate pace (see the skills and accreditation matrix for assessing employees’ skills in Figure 3-10 and the training plan in Figure 3-11 in Chapter 3).

Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of Panasonic, contrasted his organisation’s approach with that of typical Western organisations:

‘For us, the core of management is the art of mobilising and putting together the intellectual resources of all the employees in the service of the firm. Only by drawing on the combined brainpower of its employees can a firm face up to the turbulence and constraints of today’s environment.’

Overall, balance is the key to successful empowerment. Transformation needs to be a whole-brain concept. Using a left-brain only approach, one that’s all rules and structure, means everything grinds to a halt, ossifies and crumbles. But in a right-brain only approach, where there’s total creative and emotional freedom and no rules or structure, things break down and anarchy rules. A whole-brain approach is needed: appropriate rules and structure together with creativity and freedom.

The following leadership and management practices must be established:

- Developing people

- Coach and train people during new assignments

- Help people develop their skills

- Building trust

- Promote an atmosphere of co-operation

- Trust people to do an effective job

- Promoting autonomy

- Encourage people to take the initiative

- Provide appropriate coaching and support when needed

- Encouraging openness

- Forgive mistakes made by others

- Admit to mistakes

- Recognising accomplishments

- Celebrate successes

- Reward people for innovations

- Shaping direction

- Provide a vision of the future

- Take on controversial activities

- Demonstrating objectivity

- Use facts in decision-making

- Respond to facts rather than unsubstantiated data

Maintaining focus on the overall transformation

The main thing must always be the main thing if the transformation journey is to stay on track. From time to time you need to take stock and review just where your time is being spent – you should be crystal clear on what and what isn’t important.

Becoming sidetracked and tempted down some interesting improvement diversions is all too easy. Before darting off, ask yourself whether these opportunities will be helping you progress to True North. Take special care to avoid scope creep, whereby the project keeps growing. Spend time up front to get the scope right and avoid wasting time later on.

Naturally, a vision of the future that captures the energy and commitment of the people in the organisation is essential. But where the journey is likely to take some time, do remember to take the occasional pit stop to recharge everyone’s batteries and recognise the progress made so far.

DMAIC projects always start with a problem statement. In the context of business transformation, the project should be related to progressing strategy deployment.

DMAIC projects always start with a problem statement. In the context of business transformation, the project should be related to progressing strategy deployment. The example below highlights how Lean Six Sigma works in a service process. It describes an insurance company’s new business team as it processes new policy applications. The measurable customer requirements, the CTQs (critical to quality requirements), indicated that policies must be issued within five working days and the documentation must be error free.

The example below highlights how Lean Six Sigma works in a service process. It describes an insurance company’s new business team as it processes new policy applications. The measurable customer requirements, the CTQs (critical to quality requirements), indicated that policies must be issued within five working days and the documentation must be error free. If you want to reach True North, personal objectives must reflect that. If the executives’ bonus structure rewards travelling south, the strategy will clearly fail!

If you want to reach True North, personal objectives must reflect that. If the executives’ bonus structure rewards travelling south, the strategy will clearly fail! Jack Welsh, former CEO of General Electric, sent a very clear message to his managers when he told them no one would be promoted until they’d led or championed an improvement project. Guess what happened?

Jack Welsh, former CEO of General Electric, sent a very clear message to his managers when he told them no one would be promoted until they’d led or championed an improvement project. Guess what happened? Generate your own list of challenges using negative brainstorming. This technique turns brainstorming on its head. So, for example, rather than brainstorming ‘What reasons may account for project failure?’ you can instead brainstorm ‘How can we ensure projects fail?’ This activity is good fun, albeit somewhat disturbing when you consider the output and then realise you’re actually doing some of these things.

Generate your own list of challenges using negative brainstorming. This technique turns brainstorming on its head. So, for example, rather than brainstorming ‘What reasons may account for project failure?’ you can instead brainstorm ‘How can we ensure projects fail?’ This activity is good fun, albeit somewhat disturbing when you consider the output and then realise you’re actually doing some of these things.