Chapter 1

Introducing Lean Six Sigma

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding what transformation means

Understanding what transformation means

![]() Breaking down the PDCA cycle

Breaking down the PDCA cycle

![]() Choosing between DMAIC or DMADV

Choosing between DMAIC or DMADV

As well as an overview of the broad content of this book, this chapter provides an introduction to what we mean by transforming an organisation and why your organisation may need it. We take a brief look at the DRIVE and Plan, Do, Check, Act models that provide the framework for deploying the strategy that leads to transformation. The chapter also provides a reminder of the key principles of Lean Six Sigma and the DMAIC and DMADV methods used to improve existing processes or design and create new ones.

Defining Transformation

The Oxford English Dictionary describes transformation as ‘a marked change in form, nature or appearance’. And in the context of business transformation that definition is a pretty accurate fit.

You may need to address organisational problems such as high error rates in dealing with customer orders, which in turn lead to increased complaints and ultimately loss of market share. But a burning platform situation may not exist at all. The organisation may be targeting growth in some way, perhaps through an entirely new market or product range, for example. It might even be seeking to change its identity and with it the perceptions of the marketplace.

One way or another, though, your organisation is seeking a marked change, be it in performance, appearance or both. And almost certainly, the change is likely to require a change of thinking and behaviour on the part of the people in the organisation, especially the leaders and managers.

Whatever the rationale that’s driving the need for transformation, a crystal clear link to the organisation’s strategy and its deployment is essential. The Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycle comes into play here in terms of the planning for and support of the transformation and the deployment of strategy.

A business transformation takes time to achieve and requires the organisation to utilise an effective implementation methodology – the DRIVE model (Define, Review, Improve, Verify and Establish) – and to create a capability maturity roadmap to support the changes. The capability maturity roadmap provides a phased approach to deploying Lean Six Sigma capability in the organisation. Chapter 3 covers the DRIVE model and the capability maturity roadmap in more detail.

This book focuses on Lean Six Sigma as the vehicle to support and drive the changes needed in thinking and behaviour, and that also provides a framework for the improvement projects that emerge through the journey ahead. We provide only a relatively brief summary of the ins and outs of Lean Six Sigma, however, as it is described in detail in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley).

Before we look at Lean Six Sigma in a little more detail, however, we need to take a look at the PDCA cycle.

Introducing the Plan–Do–Check–Act Cycle

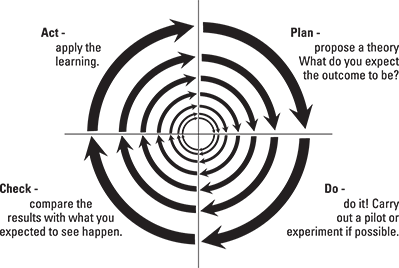

The Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycle, as illustrated in Figure 1-1, provides a foundation for strategy deployment.

Figure 1-1: The Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycle.

Although not overtly referred to in the Lean Six Sigma methodology, the PDCA cycle is very much at the heart of the DMAIC improvement method described in Chapter 2. The PDCA cycle breaks down as follows:

- Plan: This element refers to your theory or hypothesis. If you do this, you expect that to happen.

- Do: Here you put your theory to the test. Ideally, you undertake pilot activities or tests.

- Check: Here you look to see whether the outcomes of your actions in the Do phase are producing the results your Plan led you to expect. To do that properly, you need to ensure you gather the right data and also that you’re viewing things from the correct perspective, something you will have determined in the Plan phase. Lean Six Sigma helps you get the measures right, but you need to recognise the importance of going to see actual results in the workplace – the ‘gemba’, as the Japanese call it.

- Act: Depending on your findings in the Check phase, you may need to make adjustments to the theory you developed in the Plan phase and then run through another PDCA cycle. If things have gone according to plan, however, you can act to put your theory formally in place, or run a larger test depending on the scale of the pilot.

We return to the PDCA cycle throughout the book.

Showing the Way with Lean Six Sigma

To apply the Lean Six Sigma approach successfully, you need to recognise the need for different thinking. To paraphrase Albert Einstein:

‘The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them.’

You want to change outcomes but you also need to realise that they are themselves the outcomes from your systems. Not the computer systems, but the way in which people work together and interact. And these systems are the product of how people think and behave. So, if you want to transform and change the outcomes you have to change your systems, and to do that, you have to change your thinking.

You need to adopt thinking that focuses on improving value for the customer by improving and smoothing the process flow and eliminating waste. Since the establishment of Henry Ford’s first production line, lean thinking has evolved over many years and in the hands of many people and organisations, but much of the development has been led by Toyota through the creation of the Toyota Production System. Toyota was able to build on Ford’s production ideas to move from ‘high volume, low variety’ to ‘high variety, low volume’.

Six Sigma thinking complements the lean approach through a systematic and robust approach to improvement that is based on management by fact. In particular, it looks to get the right data, in order to understand and reduce the variation in performance being experienced in the organisation’s products, services and processes.

Identifying the key principles of Lean Six Sigma

Lean is not about cutting things to the bone. Rather, it’s about providing value for your customers. Taiichi Ohno, the architect of the Toyota Production System, sums up the approach in a nutshell:

‘All we are doing is looking at a time line from the moment the customer gives us an order to the point when we collect the cash. And we are reducing that time line by removing the non-value-added wastes.’

And value is what customers are looking for. They want the right products and services, at the right place, at the right time and at the right quality. Value is what the customer is willing to pay for.

Explaining Lean thinking

We’re sure you’re aware of the half-full, half-empty glass analogy applied to whether someone looks on the positive or negative side. A Lean practitioner might well respond by saying ‘it’s the wrong sized glass!’ Either way, you first need to understand the customer and their perception of value. You have to know how the value stream operates and enable it to flow, perhaps by removing waste and non-value-added activities.

Lean thinking also means looking for ways of smoothing and levelling the way the work flows through the process and, where possible, working at the customer’s pace – in other words, it’s a pull rather than a push process. And, of course, in the pursuit of perfection, you’re always looking to improve things through the concept of continuous improvement.

Linking up with Six Sigma thinking

Six Sigma thinking is very similar to Lean thinking. Six Sigma also focuses on the customer. A key principle of Six Sigma is understanding customer requirements and trying to meet them. If you don’t understand those requirements, how can you expect to provide the customer with value?

Again, as with Lean thinking, to understand your processes you need to understand how the work gets done. Data comes into play more so with Six Sigma thinking than with Lean thinking. If you’re to manage by fact, you need to have the right measures in place and the data presented in the most appropriate way.

An appreciation and understanding of the variation in your process results enables you to more effectively interpret your data and helps you know when, and when not, to take action.

Six Sigma thinking also means equipping the people in the process so that they’re fully involved and engaged in the drive for improvement.

Accessing the best of both worlds

Similarity and synergy exist between Lean thinking and Six Sigma and combining the two approaches creates a ‘magnificent seven’ of Lean Six Sigma key principles:

- Focus on the customer.

- Identify and understand how the work gets done – the value stream.

- Manage, improve and smooth the process flow.

- Remove non-value-adding steps and waste.

- Manage by fact and reduce variation.

- Involve and equip the people in the process.

- Undertake improvement activity in a systematic way.

In Lean Six Sigma the key focus is on the customer. You need to understand their perception of value and their critical-to-quality customer requirements – the CTQs. The CTQs provide the basis for your measurement set; you can measure how well you’re performing in relation to them. Focusing on the customer, and the concept of value-adding, is especially important because, in our experience, when we start work with new clients, typically only 10 to 15 per cent of process steps add value and often represent only 1 per cent of total process time. Naturally, many organisations have discovered that their continuous improvement efforts have significantly improved process performance; unfortunately, plenty still exist that have yet to realise the benefits of Lean Six Sigma.

Lean Six Sigma provides a set of criteria to help you determine whether or not a process step is value-adding:

- The customer has to care about or be interested in the step. If they knew you were conducting this step, would they be prepared to pay for it?

- The step must either change the product or service in some way or be an essential prerequisite.

- The step must be actioned ‘right first time’.

A value-adding step meets all three criteria. Non-value-adding steps must be removed. Obviously, some steps may not meet these criteria but are nonetheless essential for regulatory, fiscal or health and safety reasons, for example. By identifying and understanding how the work gets done – the value stream – you highlight the non-value-adding steps and waste. In doing so, you ensure that the process is focused on meeting the CTQs and adding value. Understanding, managing and improving the value stream is key to eliminating non-value-adding steps as it sets out all of the actions, both value creating and non-value creating, that bring a product or service concept to launch or process a customer order.

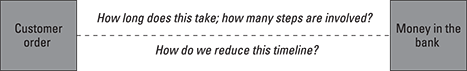

Ensuring the senior team’s understanding of the organisation’s high level value streams provides a foundation for the prioritisation of value-adding steps in the various processes. ‘Order to Cash’ is a good example and is illustrated in Figure 1-2. Can you identify process steps that can be removed or reduced in some way? How can you close the gap, speed up the process and smooth the flow?

Figure 1-2: Looking at ‘Order to Cash’: Lean Six Sigma thinking in a nutshell.

Managing, improving, and smoothing the process flow provides another example of different thinking. If possible, use single piece flows, moving away from batches or at least reducing batch sizes. Either way, identify the non-value-adding steps in processes and try to remove them; at the very least, look to ensure that they don’t delay value-adding steps. The concept of pull, not push, links to understanding the process and improving flow.

Pushing not pulling can be an essential element in avoiding bottlenecks. Overproduction, or pushing things through too early, is a waste. One way to improve flow and performance is to identify, remove and prevent waste or, as the Japanese call it, ‘muda’.

Managing by fact, using accurate data, helps you avoid jumping to conclusions and solutions. You need the facts! And that means measuring the right things in the right way. Data collection is a process and needs to be managed accordingly. Using control charts enables you to interpret the data correctly and understand the process variation. You’ll then know when, and when not, to take action and will be able to accurately describe the state of your process. You can find out more about control charts in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley) and also in SPC in the Office by Mal Owen and John Morgan (Greenfield Publishing).

Involving and equipping the people in the process is vital. The ‘soft stuff’ mustn’t be overlooked. In simple terms, the soft stuff refers to how you work with the people involved in the process, and the key stakeholders who can so easily make or break the improvements you plan. A key stakeholder is anyone who controls critical resources, who can block the change initiative by direct or indirect means, who must approve certain aspects of the change strategy, who shapes the thinking of other critical parties, or who owns a key work process impacted by the change initiative. And it’s about their acceptance of what you’re trying to do. You may well have developed an ideal solution, but its effectiveness is dependent on how well you’ve gained acceptance from the people in the organisation. Chapters 2 and 3 cover the soft stuff in more detail.

Lean Six Sigma provides two frameworks for improvement. The action you take in improving or designing your processes needs to be undertaken in a systematic way. DMAIC provides the framework to improve existing processes and DMADV covers the design of new products, services and processes.

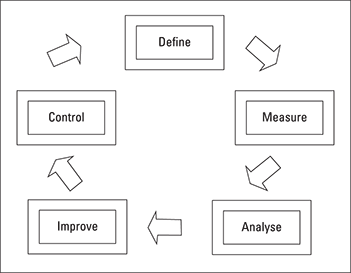

Improving Existing Processes with DMAIC

The DMAIC cycle is a systematic approach to solving problems and improving existing processes. DMAIC stands for Define, Measure, Analyse, Improve and Control, and these phases are illustrated in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3: The DMAIC cycle.

Isolating the problem

When you start any new improvement project, an essential ingredient for success is ensuring that you and your team have a clear understanding of why the project is being undertaken and what it’s trying to achieve. With a DMAIC project, you start with a problem that needs to be solved.

Before you can solve a problem, however, you need to clearly define it, which isn’t always as straightforward as it might sound. You might not have all the information you need to write a clear problem statement, for example. The Measure phase helps you understand things more clearly and, where necessary, you can update the problem statement and the improvement charter in the light of your new-found knowledge. See Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley) for more about problem statements and improvement charters.

Working out what’s happening

In simple terms, the Measure phase is about understanding how the work gets done and how well it gets done. To understand the current situation, you need to know what the process looks like and how it’s performing. You need to understand what’s meant to happen, and why. You also need to recognise how your process links to your customer.

Naturally, being aware of current performance is essential – this becomes your baseline – but it will also be helpful to know what’s happened in the past.

Understanding why it’s happening

In the Measure phase you discovered what’s really happening in your process. Now, in the Analyse phase, you need to identify why it’s happening, and determine the root cause. You need to manage by fact, though, so you must verify and validate your ideas about possible suspects. Jumping to conclusions is all too easy. The usual suspects may well be innocent bystanders.

You can find the root cause using one of two approaches: either through an assessment of the process and how it flows or through analysis of the data. Often, you need to use both. Clearly, the extent of analysis required will vary depending on the scope and nature of the problem you’re tackling and, indeed, what your Measure activities have identified.

Coming up with an idea

The Improve phase breaks into three distinct parts. You need to come up with your possible solutions, select the most appropriate and make sure that they’ll work. This phase of DMAIC is where most people want to start!

Now you’ve identified the root cause of the problem, you can begin to generate improvement ideas to help solve it. Your ideas will need to be reviewed and prioritised and perhaps even tested on a small scale before selecting the most appropriate. Sometimes, the improvement solution is very straightforward – or at least it might seem to be. Your value-adding analysis may have identified several steps that can be removed from the process, for example.

The chosen solution may need to be developed in more detail, but will almost certainly need to be properly piloted – the PDCA cycle comes into play here (see the ‘Introducing the Plan–Do–Check–Act Cycle’ section earlier in this chapter).

Making sure it’s really sorted

After all your hard work, you need to implement the solution in a way that ensures that you make the gain you expected and maintain it! If you’re to continue your efforts in reducing variation and cutting out waste, the changes being made to the process need to be consistently deployed and followed.

A control plan is vital and is another stage in really getting to grips with working on the process. Getting the right measures in place is an essential element of control and you need to be satisfied that the data collection plan has been effectively deployed. The Control phase helps the organisation move towards a situation where processes are genuinely managed. Data collection and the development of a data collection plan are covered in See more about data collection and control plans in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley).

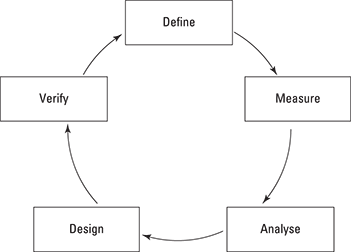

Designing New Processes with DMADV

DMADV stands for Define, Measure, Analyse, Design and Verify, and is a framework for designing new products, services or processes (see Figure 1-4). You can also use DMADV when an existing process is so badly broken that it’s beyond repair.

Figure 1-4: The DMADV cycle.

As with DMAIC, you may well find yourself moving back and forth through the phases – it’s not necessarily linear.

The DMADV framework is focused on the customer and their CTQs. Where possible, you have to listen to and understand the voice of the customer, but you may also need to look beyond the voice of the customer in developing your designs.

As with DMAIC, managing by fact and not speculation ensures that new designs reflect customer CTQs and provide real value to customers in line with the principles of Lean Six Sigma. However be aware that sometimes customers may not realise what’s possible, or what they want, as Steve Jobs recognised:

‘A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.’

DMADV projects are often concerned with introducing radical change or transformation within an organisation.

Defining the design

The Define phase is concerned with scoping, organising and planning the journey for your design project. Understanding the purpose, rationale and business case is important, as well as knowing who you might need to help you, and how you’ll go about managing things. Thus, understanding the boundaries of the project, including the processes, market(s), customers and stakeholders involved, is vital.

An essential ingredient for success is ensuring that you and your team have a clear understanding of why the project is being undertaken, and what it’s trying to achieve. How does it link to your strategy, for example?

The Define phase is all about making sure that such understanding happens. You need to bring together the right people at the start, making sure that the relevant departments and functions are represented. All too often, this isn’t the case and the definition and scope of the project suffers.

Getting the measure of the design

The Measure phase is vital as it provides the framework around which your design can be built, and the basis for the design decisions needed in further phases. This phase focuses on defining and understanding customer needs, and understanding the different customer segments is essential. Design for Six Sigma (DfSS) projects using DMADV typically seek to optimise the design of products, services or processes across multiple customer requirements, so a detailed understanding of such requirements is essential.

The next step is to translate customer needs into measurable characteristics (CTQs), which become the overall requirements for the product, service or process. Your aim is to fully understand customer requirements, define the measures and set targets and specification limits for CTQs. If you’re designing new products or services, you need to make sure that the design can be produced with existing processes; if not, you’ll need to create new processes to accommodate the new design. Considering process capability at this phase, rather than after the design is complete, is a hallmark of DfSS. Six Sigma performance is dependent on the quality of the processes you maintain or create.

Conducting analysis

The Analyse phase involves developing the functional specification and high level designs. Analyse begins the process of moving from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’ – from what the customer needs to how you might achieve it. You begin by mapping the CTQs onto the internal functions and then look at alternative design concepts; as vacuum cleaner revolutionary James Dyson stated:

‘Design means how something works, not how it looks – the design should evolve from the function.’

For a service, analysis means identifying the key functions; for a more tangible product, it means identifying its key part characteristics. Typically, the sub-system characteristics are developed next, followed by the components (parts) of the sub-system.

Functions are what the product, service or process has to do in order to meet the CTQs identified and specified in the design process. In a service environment, functions are best thought of as key high level processes to be considered. So, for example, the product or service being designed could be a telephone ordering service, with a design goal of an order placement within five minutes. The functions involved could include ‘answer the call’, ‘check requirements’, ‘check stock’ and ‘place order’.

The second part of the Analyse phase involves analysing and selecting the best design concept and beginning to add more details to it. Each element of the design should be considered in turn, and high level design requirements specified for each.

You also need to consider how the different components fit together and interact with each other. This process usually involves creating several high level designs, assessing the suitability of each, and then selecting the best fit.

Developing the design

The Design phase is also in two parts. It begins by developing the ‘how’ thinking in more detail. The objective is to add increasing detail to the various elements of the high level design. The emphasis is on developing designs that will satisfy the CTQ requirements of the process outputs.

The design process is iterative – the high level design was established in the Analyse phase; now the design is specified at a detailed enough level to develop a pilot and test it. The detailed design activities are similar to those in the high level design phase but with a significantly lower level of granularity.

This step integrates all of the design elements into one overall design. Finally, the lowest-level specification limits, control points and measures are determined. These will form the basis of the control plan that needs to be in place following implementation.

Before implementation, however, you need to pilot the design. Enough detail should now be available to test and evaluate the capability of the design by preparing a pilot in the second part of the Design phase. The pilot must be effective and realistic.

Making sure the design will work

The design is piloted and assessed in the Verify phase and, subject to any adjustments that follow the pilot, implementation and deployment follow. As with DMAIC, the final step in the cycle is to assess the achievements made and lessons learned. The results are verified in relation to the original CTQs, specifications and targets. The project is closed only when the solution has been standardised and transitioned to operations and process management.

You need to ensure that no black holes exist in the handover to the process owner or operational manager. You must work closely with your team to achieve a well-planned and well-documented transition.

Recognising DMAIC and DMADV Transition Points

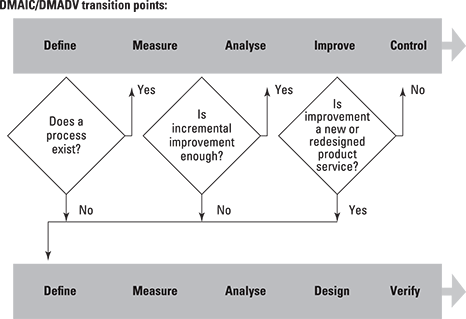

It’s possible to start a project using the DMAIC method only to find yourself changing to DMADV at some point. Figure 1-5 illustrates the likely decision points in transitioning from one method to the other.

Figure 1-5: Choosing the right method.

Figure 1-5 highlights several decision points at which you might consider transitioning from DMAIC to DMADV. The decision is clear if you have no existing process – you have to design one and thus DMADV is the route to take. But you might find yourself starting a DMAIC project in the firm belief that you’ll be able to remedy the problem you’re tackling by improving a current process. As you gather information in the Measure phase, however, you may find yourself having second thoughts, and as you move into the Analyse phase you realise that incremental improvement really won’t be sufficient.

You may also encounter occasions on which your conclusions in the Improve phase lead you to the recognition that the solution needs to be something new rather than an enhancement of the existing processes. Asking some searching questions might help you decide:

- Is a process already in place? Here we refer to a real process, not a series of cobbled together steps that try to get something done. If no process exists, switch to DMADV to create one.

- Is the process beyond repair? A process may be in place but it isn’t really working, and trying to improve it resembles Mission Impossible. If so, start again using DMADV.

- Finally, is it a problem? Remember that DMAIC projects begin with a process problem. But, even if a problem does exist, it may still need to be solved using DMADV.

Bringing It All Together

This chapter has provided an overview of the Lean Six Sigma concepts, principles and methods, for both improvement and design projects. These projects are component parts of the transformation change that will not only enhance performance but also drive, and demand, a change in thinking and behaviour across your organisation.

Strategy deployment links your business strategy to a programme of projects to deliver that transformation and is covered in Chapter 8.

The value stream and the process are one and the same; they’re simply different terms. Essentially, you’re talking about ‘how the work gets done’.

The value stream and the process are one and the same; they’re simply different terms. Essentially, you’re talking about ‘how the work gets done’. Ensure that you measure what’s important to the customer, and remember to measure what the customer sees. Gathering this information helps focus your improvement efforts and prevents you going off in the wrong direction.

Ensure that you measure what’s important to the customer, and remember to measure what the customer sees. Gathering this information helps focus your improvement efforts and prevents you going off in the wrong direction.