To make use of any Linux system, you need to be comfortable with

Linux files and directories (a.k.a. folders). In

a “windows and icons” system, the files and directories are obvious on

screen. With a command-line system like the Linux shell, the same files

and directories are still present but are not constantly visible, so at

times you must remember which directory you are “in” and how it relates

to other directories. You’ll use shell commands like cd and pwd

to “move” between directories and keep track of where you are.

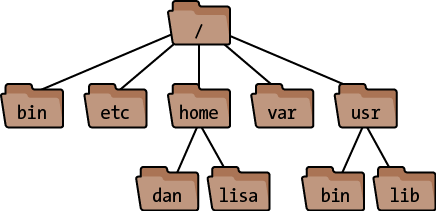

Let’s cover some terminology. As we’ve said, Linux files are collected into directories. The directories form a hierarchy, or tree, as in Figure 1-3: one directory may contain other directories, called subdirectories, which may themselves contain other files and subdirectories, and so on, into infinity. The topmost directory is called the root directory and is denoted by a slash (/).[3]

Figure 1-3. A Linux filesystem (partial). The root folder is at the top. The “dan” folder’s full path is /home/dan.

We refer to files and directories using a “names and slashes” syntax called a path. For instance, this path:

/one/two/three/fourrefers to the root directory /, which contains a directory called one, which contains a directory two, which contains a directory three, which contains a final file or directory, four. If a path begins with the root directory, it’s called an absolute path, and if not, it’s a relative path. More on this in a moment.

Whenever you are running a shell, that shell is working “in” some directory (in an abstract sense). More technically, your shell has a current working directory, and when you run commands in that shell, they operate relative (there’s that word again) to the directory. More specifically, if you refer to a relative file path in that shell, it is relative to your current working directory. For example, if your shell is “in” the directory /one/two/three, and you run a command that refers to a file myfile, then the file is really /one/two/three/myfile. Likewise, a relative path a/b/c would imply the true path /one/two/three/a/b/c.

Two special directories are denoted . (a single period) and .. (two periods in a row). The former means your current directory, and the latter means your parent directory, one level above. So if your current directory is /one/two/three, then . refers to this directory and .. refers to /one/two.

You “move” your shell from one directory to another using the

cd command:

$ cd /one/two/three

More technically, this command changes your shell’s current working directory to be /one/two/three. This is an absolute change (since the directory begins with “/”); of course you can make relative moves as well:

$ cd d Enter subdirectoryd$ cd ../mydir Go up to my parent, then into directorymydir

File and directory names may contain most characters you expect: capital and lowercase letters,[4] numbers, periods, dashes, underscores, and most symbols (but not “/”, which is reserved for separating directories). For practical use, however, avoid spaces, asterisks, parentheses, and other characters that have special meaning to the shell. Otherwise, you’ll need to quote or escape these characters all the time. (See Quoting.)