2 Well-Being in Theory and Practice

2.1 INTRODUCTION

International development institutions have long since adopted approaches that facilitate development beyond a poverty-reduction agenda. The United Nation's ‘Declaration on the Right to Development’ (1986) and the UNDP stress that all peoples should be able to live under conditions that allow them to pursue their well-being. Whereas poverty reduction is part of that equation, so are the social and institutional processes that promote agency, formal and informal education, capabilities, intuitive dignities, innovation and cultural expression. The well-being perspective runs counter to a focus on poverty defined in terms of ‘lack of income’ and points to the interlocking effects of institutions on quality of life and satisfactions, and vice versa. In the early 1990s the UN, under the guidance of Mahbub ul Haq and his team of colleagues, including among others Amartya Sen,1 designed the Human Development Index (HDI)—a composite index of national averages of education, life expectation and income level. The HDI in turn was inspired by the basic needs index of Peter Townsend (1979), as well as the capabilities approach by Amartya Sen (1985). The HDI did not cover all dimensions of well-being but was considered the best possible construct at the time, particularly because the type and quality of data were not sufficient, especially in developing countries.

The capabilities approach was Sen's original development model as an enhancement of following an individual-utility-based economics approach (1985, 1988). Poverty, according to Sen, should be defined as a deprivation of capabilities. Capabilities are defined as the set of alternative combinations of functionings an individual can achieve and consists of two communicating parts: functionings and freedom of opportunity (Sen 1985). The capabilities approach drew attention to the multidimensions of poverty, the importance of freedoms, inequalities in individual capability endowments and opportunities to advance in life. In later works by Sen (1993 onwards), he acknowledged that the concept of welfare—or, ‘how someone is faring economically’—was a rather limited and individualistic conception of human development. In subsequent works we find that Sen expanded the capabilities approach to the broader notion of well-being (Sen 1993, 2000). The capabilities approach as it is connected to the idea of well-being was elaborated upon in respect to people's freedoms, quality of life including psychological well-being and the role of institutions. This movement was initiated by important political philosophy and development thinkers such as Martha Nussbaum (1993, together with Sen), Sudhir Anand (2000, also together with Sen), and David Clark (2002). More recently, Allister McGregor (McGregor 2004; Gough and McGregor 2007) is trying to promote a well-being centered approach to development research and interventions.

This chapter will introduce the contributions of a well-being approach in the research process. In addressing theory in section 2.2, we will address the question of how the well-being approach expands upon poverty approaches. Sen (2000), Chambers (1983), and Putnam (2000) (among others in humanities) are moving beyond a theoretical conception of inequality as a lack of capital assets. The well-being approach takes these theoretical approaches and adapts methodological practices that address the complexities of the development process. In section 2.3, we will therefore critically discuss the research methodology implied by a well-being approach in development research. What are the current challenges of operationalizing the approach in a consistent manner? Some principal outcomes of studies applying a well-being approach in practice will be reviewed in section 2.4. The empirical research coming out is particularly useful in pointing out areas in which (community) development is ‘frustrated’, by means of comparing people's priorities in life with achieved satisfactions. Finally, in section 2.5 we will zoom in on the cultural imperatives underlying the well-being approach and what this means at the epistemological level of research on development, before concluding in the final section.

2.2 THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE WELL-BEING APPROACH

Well-being is necessarily a normative concept, encompassing both objective and subjective ideas of what it means to live ‘well’ and ‘develop’. As defined by the WeD2 working group at the University of Bath, ‘Well-being is a state of being with others, where human needs are met, where one can act meaningfully to pursue one's goals, and where one enjoys a satisfactory quality of life’. This hybrid definition accepts well-being as a state that is objectively and subjectively generated through intra-and interpersonal relationships. A conception of well-being must take into account the material, relational, and cognitive capabilities forming the needs and goals of an individual or group of individuals.

Well-being has been pursued as a concept since at least the time of Aristotle, but has been neglected in development theory and institutional practices due to its plurality and normativity. The factors that contribute to well-being are dependent upon multiple pathways, institutions and embedded cultural reactions particular to time and place. A development framework based on a well-being approach must take into account the structural processes that continuously interact with capital flows. Adherence to the poverty approach precludes the work of development from taking into account the exploitative processes that lead to durable and categorical inequality (Tilly 1998); accepting that a lack of material assets is the only causal mechanism of poverty ignores the social and institutional processes that promote agency, formal and informal education, capabilities, intuitive dignities, innovation and cultural expression.

Theoretical Developments

Theoretical implications of how well-being impacts development have been constructed in recent decades. The definition provided above was formulated by the Well-being in Developing Countries (WeD) working group at the University of Bath, established by Ian Gough and Allister McGregor. The well-being approach used in the group's research is based on some basic assumptions about the way people(s) pursue their needs, goals, and overall happiness. The first is that people have preferences; bargaining occurs within and between individuals, communities and institutions to build adaptive and innovative preferences, perceived needs and goals (McGregor 2007a). This factor relates to Nussbaum and Sen's (1993) work on quality of life and how intuitive dignities and interpersonal norms create pathways for individuals and communities to achieve well-being. Integrating preferences and interpersonal bargaining into a well-being in development model looks beyond a poverty approach because a utility-based conceptual framework disregards freedoms, emotions, affiliations and agency.

Second, a well-being approach assumes that the needs of an individual transcend material capitals and include ‘health, autonomy, security, competence and relatedness, the satisfaction of which at a basic level enhances objective well-being everywhere’ (WeD 2007). The acquisition of nonmaterial assets, such as favors, social bonds, trust and motivation, increases the perception of well-being on an individual and community level. Again, this factor evolves from the capabilities approach (Nussbaum and Sen 1993) and includes evidence from social capital research on the relational aspect of well-being. The norms and networks that enable people to act collectively are built on relationships of reciprocity and bargaining between nonmaterial assets (Putnam 2000; Woolcock and Narayan 2000). From a governance perspective, these nonmaterial assets are important to understand for building open relationships and targeted, integrative goals between agencies, institutions and recipients of development assistance.

Third, we can understand well-being as a state and a dynamic process that is incumbent on a local place but also based on aspirations and capabilities toward living well beyond a specific context. Thus, generalizability between the local and universal in a research context requires an exploration of global relationships, historically embedded processes and the politics and power involved in establishing and maintaining well-being (Gough and McGregor 2007).

Another important consideration of well-being is that it is necessarily a political concept. Tilly (1998) and Sen (1982) discuss durable inequality as an institutional mechanism born out of economic disadvantages but not necessarily a lack of assets. Tilly concludes that persistent poverty is caused by systematic exploitation and the diversion of resources; resource hoarding and price control are politically motivated forms of suppression that offer the illusion of a society with a lack of material wealth (Tilly 1998). In reality, noted Sen, the problem is not the amount of resources but the way systems and institutions appropriate them for consumption (1982). Governance priorities must reflect an understanding of the incumbent system producing durable inequality if its members intend to implement a well-being approach.

These theoretical implications have been developed over three decades but have fallen short in terms of methodological implementation. The plurality of the concept should not preclude a systematic methodology or organized base of generalizable data. The following section will outline a six-pronged methodological approach to facilitate the transition from theory to practice.

2.3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY3

The well-being approach was originally developed with the objective of explaining persistent poverty and to provide input into debates of how it can be reduced (McGregor 2007a). In general terms, well-being research seeks to answer the following questions:

- Are people's needs being met?

- Are people able to enjoy good and meaningful relationships in society?

- Are people able to act meaningfully in accordance with their goals and beliefs?

- Are people satisfied with their quality of life?

McGregor (2007a) rejects single-method measures in finding answers to these questions, as the WeD working definition of well-being demands a suite of different measurements. This section outlines a six-component methodology that can be grouped into three pairs dealing with outcomes, structures and processes:

- Objective and subjective explorations of outcomes;

- Meaningful collectivities and relational frameworks within communities and the nation state;

- Situated time and aggregated qualitative and quantitative data.

Building a mixed methodological approach to well-being does not exclude poverty approaches, but rather seeks to build a systematic framework for developing nations to use for evaluation and implementation purposes. Incorporating mixed methodology allows for multiple levels of governance to disaggregate useful data and build locally relevant and meaningful responses. The six interrelated components of the proposed research methodology include: (i) community profiles; (ii) a resources and needs questionnaire (RANQ); (iii) an income and expenditure survey; (iv) quality of life; (v) process research; and (vi) structures and regimes.

Community profiles are detailed accounts of the social, political, economic and cultural characteristics of the immediate context in which people and processes are studied. Instead of livelihood ‘capitals’, the broader concept of ‘resources’ is used to understand people's access, use and prioritization of resources within a particular context and the extent to which needs are satisfied by them. It is thus vital to understand the broader (community) context in which households and individuals have access and control over resources.

The information on resources is collected through the household resources and needs questionnaire (RANQ). Together with the community profiles, the RANQ contributes to the conceptual understanding of well-being in a specific place and time, both at the individual/household and community level. The community profiles serve the practical purpose of a ‘sounding board’ throughout the research process in regards to its angle, approach and reflection on results. The RANQ has been applied in empirical studies in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Peru and Thailand, typically to an average of 1,000 households (in urban and rural locations). The questionnaire usually consists of the following six sections: household organization; general assessment of subjective well-being; human resources; material resources; social resources; and cultural resources.

The income and expenditure survey collects both individual and households level data on (seasonal) income and expenditure patterns. This is where the methodology comes closest to the large-scale household surveys underlying much of the poverty research based on an income or consumption expenditure approach. However, given that individual data are collected, here intrahousehold analysis is an option and possible entry point into the further analysis of intrahousehold power differences and decision-making processes (e.g., according to gender, age or membership status). Subjective data on happiness and life domain satisfactions are also collected through this survey. The quality of life interview tool aims at self-evaluation by the respondent about his or her self-perceptions and achieved satisfactions of quality of life as a whole. The quality of life is then broadly defined as: “The outcome of the gap between people's goals and perceived resources, in the context of their environment, culture, values, and experiences” (Camfield et al. 2007).

The final two components, process research and structures and regimes, are both qualitative investigations with the objective of learning how different people interact with social, economic and political microprocesses, macrostructures, and regimes in their quest for well-being. The assumptions underlying the kind of mixed-methods approach pursued in well-being research does not follow from one paradigm or the other. O'Leary (2004) therefore proposes to adopt alternative quality criteria of good research that do not originate from either a positivist or postpositivist paradigm but are formulated by researchers themselves in accordance to their research objectives and underlying ontological and epistemological point of view (2004:57). The objective of most research in the field of international development studies, including well-being research, is instrumental (Sumner and Tribe 2008:69); providing more/better knowledge to policymakers and planners to solve real-world development problems is of critical usage to all nation-states. The challenge to well-being research, then, is to provide a coherent reconciliation between objective and subjective knowledge. In the following section, we will scrutinize to what extent empirical well-being research can come to a concrete assessment (or measurement) of well-being in a particular cultural context, and to what extent comparative research across locations is possible.

2.4 CURRENT AND ONGOING STUDIES

Exploring well-being in the development context is challenging because limited views of well-being will produce insufficient policies toward growth. Not only is a strong theoretical and methodological approach necessary, but so is the expressed goal and foundation of a researcher or team. WeD has tackled this issue by focusing their work in four key developing areas (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Peru and Thailand) and working through methodological approaches to build a framework in each situation. This has not only added multifaceted insights into the development issues facing these nation-states, but has given outside researchers a conceptual scheme for producing similar bodies of work in other areas or for targeting alternative components of a society's well-being.

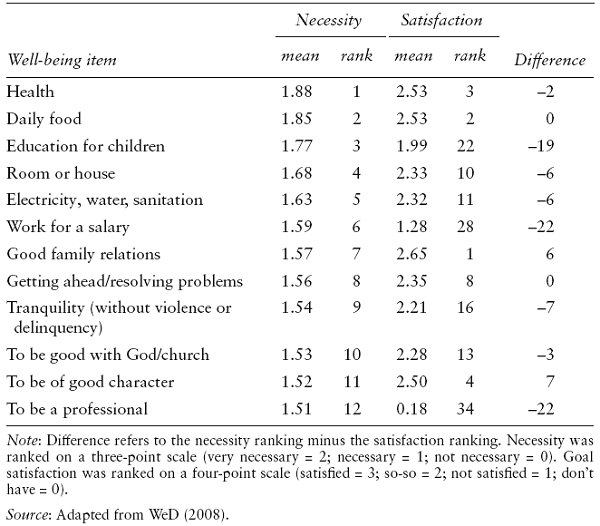

The first example shows that well-being can be ‘measured’ as a context-specific emergent concept that evolves out of a combination of sociocultural, political and economic processes and structures. In this example, we zoom in on a case study carried out in 2008 among 550 households in seven relatively poor rural and urban locations in Central Peru (WeD 2008). The case is exemplary of other well-being studies conducted in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Thailand. The households were asked to indicate their perceived levels of necessity and satisfaction with regard to thirty-four well-being items. Table 2.1 summarizes these findings. Respondents were found to be more satisfied with well-being items considered necessary. This may be a result of either/both adapted behaviors (more input and effort are given to fulfill necessities in life) or adapted goals (lower goals when more difficult to achieve) (WeD 2008:2). The minus scores in the last column of Table 2.1 signal so-called ‘development frustrations’, i.e., those areas in which negative differences occur between level of necessity and satisfaction. The largest development frustrations occur for education of children, to work for a salary and to be a professional.

Table 2.1 Well-Being and Quality of Life in a Rural Community in Peru (n = 550)

This exercise can be used for cross-locational comparison as long as identical lists of well-being items and underlying scales are being used. Cross comparisons based on different listings or underlying scales are only possible at the aggregate level. We propose to use a relative measure of aggregated well-being difference that could be of the following functional form:4

Whereby, AggDWB is the aggregate difference in well-being, N. is the necessity ranking of well-being item i; Si is the satisfaction ranking of well-being item i; and n is the total number of well-being items covered. Increases or decreases in this measure would indicate (aggregated) changes in well-being across a range of different items, and could be used as a useful development monitoring and policy impact assessment tool. Likewise, one could think of using a more differentiated measure by grouping the range of well-being items into a smaller number of targeted categories. One could use the three dimensions of well-being as category labels: ‘material’, ‘social-relational’ and ‘psychological’ well-being. The advantage of such a measure would be to reveal advances or deteriorations in different dimensions as a result of policies or structural change. Based on this threefold categorization, equation E2.1 can then be reformulated as:

Also, any other categorization that would still facilitate cross-locational comparison and bears relevance for well-being monitoring and policy analysis will do.

The second example of applied well-being research illustrates that comparative analysis across locations is possible, provided that a similar framework is used. For example, two WeD-based research publications (as chapters in the book Female Well-Being: Towards a Global Theory of Social Change, 2005) focused on women's political, social and economic equality in Bangladesh and Thailand. Following the same conceptual and methodological framework, the two research groups developed case studies investigating political structures, demographics, economic participation, literacy and education, civic leadership and aspirations for gender equality. Whereas the research context differed, a clear foundation in the well-being approach allowed these two case studies to be examined comparatively. Furthermore, interstices between how these two societies experienced female well-being, and in which dimensions changes had taken place in terms of female inclusion and gender equality, could be analyzed.

With regards to Bangladesh, Sultana and Karim (2005) showed stark gender inequalities to the disadvantage of women's health, education, social and economic networks and political status and participation. Equality in front of the law did not immediately translate into more equal social practices in this male-dominated patrilineal society. Despite female presidencies, political representation of women at the national level is lagging behind (slow) advancements for women and girls in other well-being dimensions (e.g., schooling, health, income generation). At the local government level, since 1997 the government had made it possible for women to participate by reserving one-third of the Union parishad (council) seats for women.5 However, this did not guarantee women's equal involvement in political discussion and decision making, as yet. Nevertheless, Sultana and Karim (2005) see future development potential of rural gender equality through increased political involvement by women in local governance systems.

Mee-Udon and Itarat (2005) assessed women's equality in Thailand and noted that improvements to the education sector have increased women's literacy rates and impact on the national economy. Modernization to the service, sales and professional industries since the 1950s has demanded a higher female labor force, and now 80 percent of positions are held by females in those industries. Another vast improvement of women's well-being is due to improvements in the health sector and access to contraception and family planning services; (maternal and child) mortality and fertility have both dropped significantly. Still, family planning remains a female burden, as men are not expected to prioritize sexual education and safety. Even though such measurable advancements have been made to the gendered sociocultural context in Thailand, Mee-Udon and Itarat emphasize the struggles still pertinent to women's equality. First, prostitution is still viewed by many young women as a way to gain economic agency and support their family, whereas it is actually a dangerous industry in which workers do not make a high standard of living. Second, although local political representation of women has increased, the overall and national representation of women in politics is stagnant. Even so, pointed out the authors, increased political representation of women will not necessarily improve gender equality; the need is great for active gender-sensitive peoples of both sexes to be politically motivated for progress. The move of the Thai government from a derogatory view of women to one of inclusion and promotion has been a significant change in the past century. The national plan for well-being focuses on the definition of ‘live well, be happy’, and emphasizes the central priority of Thai people to live healthily. The authors point out room for improvement in the spheres of education, political and religious representation, family health and sociocultural awareness as a way to move forward into an era of gender equality.

It should be noted that these case studies did not venture into the collection of primary data of people's perceptions on well-being and achieved satisfactions. This type of data may be more difficult to compare between countries (as opposed to within) given that perceptions and experiences of well-being are influenced by relative inequalities within countries more than between countries (Wilkinson and Picket 2009). Nevertheless, we can conclude that the ability to coordinate such research provides governments and institutions with local data, relational tools and comparative analysis to foster discussion and more inclusive growth trajectories. The plurality of the research contexts engenders a scope for further research into each local context, or for similar case studies to be carried out in other research areas.

2.5 MAKING ROOM FOR CULTURE

The (non)study of culture among development practitioners is seemingly a vestige of the development community's reluctance to integrate subjective notions of well-being into theory and practice. Reluctance to make room for culture in the study and practice of poverty alleviation is largely based on a lack of structural processes that can be measured or accounted for within conceptions of culture. But the belief that culture is a multifarious phenomenon that should only be analyzed through its parts only disengages from its influence over agency and the process of development.

According to McGregor, culture is a ‘complex system(s) of norms, values, and rules developed by particular communities which shape behavior and which are founded in their relationship to a particular natural environment or physical location’ (2004). It is important here to recognize similarities between the nature of culture and theoretical conceptions of well-being. Culture is based on preferences but also capabilities and non-material assets, and is utilized in the maintenance of social relationships and in accessing intuitive freedoms. Like well-being, culture cannot be considered residual to economics; it plays a pivotal role in the motivations, preferences and attitudes people form about their capabilities, livelihoods, and relational satisfaction. Culture is symbolic and structural, and is pluralistic in that it exists as a state but is dynamic, historically embedded and can be examined longitudinally. It is also a ‘location for contestation’, and is described by Scott (1985) as being a primary tool of resistance for underdeveloped societies.

Culture(s) creates symbolic attachments between form and meaning that are generated through complex histories and path dependencies. Culture moves beyond factors like religion and place of origin to a deeply rooted but shifting relationship between individuals and their political legitimacy. These attachments must be taken into account when analyzing the interaction with and adaptation to the effects of a culture's relation to other systems (McGregor 2004:3). This is particularly important for governance structures; understanding the politicization of well-being through the exchange of cultural variation and expressions can mediate the development of social norms between structures. A lack of material assets forms cultural attitudes and preferences in relation to institutional and governance demands, but so do ongoing relationships between individuals and communities within those institutions. Culture cannot be dissected and analyzed through its parts because it is the integration of its parts that help agents to form opinions, make decisions and create subjective impressions of what it means to live well and how to achieve that goal. Political culture cannot be studied as a disaggregate of culture as a whole, but rather should be acknowledged by governance structures to inform a relational approach to holistic well-being.

The (WeD) working group aims to implement an understanding of culture into its theoretical and methodological approach to well-being. One of the starting points of the WeD was to develop an understanding of culture in terms of structure and process, because there were few guidelines in previous literature that could assist in proceeding with culture as an analytical concept. The WeD contends that culture is a facet of structure in societies, and should be developed within the parameters of ‘a structural conception of culture’ as outlined by Thompson (McGregor 2004:4). Culture, therefore, can be analyzed as a whole and related to other structures. Culture is symbolic in its interactions, however, and the structures of any society are given meaning and shape by the culture that legitimizes it (McGregor 2004).

The work of the WeD begins with the understanding that all individuals have distinct cultural constructions, and even though there are mutual points of connection between peoples, there is no dominant thread or chain of connections within one set of people. As individuals move throughout the various structures they identify with, these threads intersect with the constraints and mobility allowed by their own material wealth as well as the relative wealth of the people around them. Material assets confront the threads of meaning incumbent to cultural construction every time a person performs a decision towards her well-being. These decisions connect a person to a personal identity, various structures and also connect her to other people in a way that is adaptive and relational (McGregor 2004). Therefore, the idea, promoted by Lewis (1998), that there exists a ‘subculture’ within societies is rejected because there is no dominant culture for anyone to be a ‘sub’ of (McGregor 2004). This notion also rejects a perspective that cultural hegemony can be asserted, maintained or usurped by individuals or structures by exclusive means of capital accumulation. Because culture as an aspect of well-being is integrated with material processes, the other factors involved in the construction of well-being can-not be viewed as inferior or illegitimate to capital. If cultural hegemony is dismissed, development practitioners need to understand what factors do indeed cause hegemonic structures to form and create ‘sub’ factions within society; this is key to understanding the sociopolitical foundations of poverty and durable inequality in the well-being approach.

Research Design and the Cultural Imperative

Accepting culture into the well-being framework demands that researchers explore how culture is embedded in our methodological process, as well as our ontological and epistemological foundation. Researchers build impressions and meaningful connections regarding the context of a research population not only based on the data collected, but also based on their own cultural interpretations. This infers important methodological considerations beyond the themes discussed in section 3, as researchers must adopt reflexivity in data analysis and awareness of personal identity issues during the research design and application of the research plan. If culture is a function of the well-being process, the ability to interpret data will be contingent on our ability to evaluate cultural distinctions and present them relative to our empirical evaluations. Here, consistency between our onto-logical/epistemological viewpoints and our methods is essential and implies plurality and hybridity between concepts (O'Leary 2004).

One technique employed by the WeD to ensure epistemological cohesiveness is to evaluate cultural variations and expressions in conjunction with ideological manifestations. Using Thompson's definition of ideology as “a coherent system of meaning, which provides a basis for purposive action”, the WeD aims to operationalize culture as being meta-ideological; culture transcends single ideologies but is always founded upon them (McGregor 2004). Approached in this way, culture must be understood as an operating force within structures that is accessed by individuals as a means of understanding what they experience. If a researcher approaches a cultural distinction with an alternative ideological representation to that of the researched population, data analysis would then be dependent on the structural consistencies of the researchers’ position. Therefore, a reflexive approach must be adopted at the epistemological level and used to evaluate competing ideologies between researcher and the researched population regarding ‘poverty’ and ‘development’. The reason that this leads to plurality is because rarely do the myriad cultural distinctions of an individual seamlessly fit an expressed or inherent ideological position; overlapping cultural cues and norms compete with ideological beliefs, for a research population as well as within the interpretations and perceptions of the researcher.

Culture and Ideology as Internal and Social Structures

People use cultural cues to resolve inconsistencies between competing ideologies both internally and externally. Internally, these cues lead to individual bargaining and the emergence of preferences, habits and the formation of perceived capabilities and entitlements. Externally, these cues lead to public discourse, exclusion, capital developments and social progress. The goal of many hegemonic structures is to create a single, monolithic culture to mediate ideological ambiguities and resolve dissent based on personal perception or emotional responses. This ideal is mythical. However, such structures insist on maintaining this mythical narrative of a cohesive structure in order to maintain an existing order or convince a population of necessary change (McGregor 2004).

Instead of the existence of a single cultural narrative, hegemonic structures create monolithic ideological structures and use cultural tools to maintain power over people. Culture becomes the ‘arena of contestation in which symbols, discourses, and identities are drawn to secure allocation of resources’ (Thompson, in McGregor 2004). In this case, resources not only refer to material assets but capitals and capabilities. With this in mind, we can understand the imperative of distinguishing between cultural and ideological structures within a research population; how individuals access well-being is relational to competing affiliations and livelihood needs. If we are willing to integrate culture into a well-being approach, there is a risk of homogenizing culture as a structure to the point of forming metacultural conceptualizations that verge on the ideological. To dismiss the idea of hegemonic culture(s) means doing so in our analysis, as well. This maintains that inconsistencies and pluralistic meanings must be resolved through a mixed-method pursuit of approximate truth in our research design.

2.6 CONCLUSION

Poverty approaches in recent decades have moved away from a narrow definition of poverty as being a lack of material assets toward an integrated and pluralistic view of developing societies. The well-being approach redefines the goals of development practitioners who recognize that the basic needs of individuals include health, security, autonomy, competence, and relational capabilities. Building off of Sen's (1993 onwards) capabilities approach and work within themes of social capital (Putnam 2000) Gough and McGregor (2007) have been working with a reflexive, intuitive model for how to achieve the measurement and promotion of well-being. This model takes into account the relational nature of people's agency, the sociopolitical structures that form local and timely norms, and how this web of factors interacts with the market and personal economy. This model also works within a conception of culture as a complex and dynamic process that forms the intuitive behaviors of individuals and communities. By accepting culture as a pervasive structure in the formation of people's well-being, one must recognize the potential for assessing and building upon well-being as a comprehensive lens into the capabilities, entitlements and agency impacting people's development.

Theoretical advancements must be accompanied by a clear methodological process, which was provided in section 3 as a six-component suite of tools for researchers to build flexible and adaptive frameworks. We showed that well-being can be measured through a mixed-method approach including community profiling, an income and expenditure survey and the resources and needs questionnaire; these methods allow researchers to combine locally relevant knowledge and tools developed from the Human Development Index to triangulate proper assessments of people's perceived and actual needs and well-being. The work of the WeD has been essential to paving the way for future well-being researchers by building a solid conceptual scheme and a body of contextual data that promotes this type of mixed-method research. Evidence from WeD studies, discussed in section 4, demonstrated the merits of the well-being approach for longitudinal assessments of development and for its ability to focus on the sociopolitical, economic and cultural constraints to well-being. Studies between nation-states can be compared not to evaluate which society is more or less developed but to discover the mechanisms relevant for achieving overall well-being, and the context-specific triggers that enable or diminish a society's ability to achieve perceived and actual satisfaction.

LIST OF ACRONYMS

RANQ—Resources and Needs Questionnaire

UN—United Nations

UNDP—United Nations Development Program

WeD—Well-Being in Developing Countries

NOTES

1. This team included Amartya Sen, Frances Stewart, Paul Streeten, Gustav Ranis, Keith Griffin, Sudhir Anand and Meghnad Desai.

2. Well-being in Developing Countries: http://www.welldev.org.uk/.

3. This section is largely based on McGregor (2007a) and WeD Toolbox (2008).

4. This formula is based on Pouw (2011).

5. The Union parishad (council) is the second tier of the four-tier local governance system. Each parishad covers some 10 to 15 villages (Sultana and Karim 2005:88).

REFERENCES

Anand, Sudhir, and Amartya Sen. 2000. “The Income Component of the Human Development Approach.” Journal of human Development 1: 83–106.

Camfield, Laura, Allister McGregor and Jorge Yamamoto. 2007. “Quality of Life and Well-being.” WeD Working Paper. Bath, UK: University of Bath.

Chambers, Robert. 1983. Rural Development: Putting the Last First. New York: John Wiley.

Clark, David A. 2002. Visions of Development: A Study of Human Values. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Gough, Ian, and Allister McGregor. 2007. Well-being in Developing Countries: From Theory to Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, Oscar. 1998. “The Culture of Poverty.” Society 35: 7–9.

McGregor, Allister. 2004. “Cultures and the Construction of Well-being.” Paper presented at the Anthropological Perspectives on Well-Being conference at the University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, September 2–5, 2004.

McGregor, Allister. 2007a. “Well-being in Developing Countries.” Presentation at the University of Amsterdam Annual IDS lecture series Priorities of the Poor, Amsterdam, September 6, 2007.

Mee-Udon, Farung and Ranee Itarat. 20050 “Women in Thailand: Changing the Paradigm of Female Well-being.” In Female Well-being: Toward a Global Theory of Social Change, edited by Janet Mancini Billson and Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, page #s. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Nussbaum, Martha. 1993. “Non-Relative Virtues: An Aristotelian Approach.” In The Quality of Life, edited by Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen, 242–269. New York: Oxford Clarendon Press.

Nussbaum, Martha, and Amartya Sen, eds. 1993. The Quality of Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

O'Leary, Zina. 2004. The Essential Guide to Doing Research. London: Sage Publications.

Pouw, Nicky. 2011. “Toward more Inclusive Economics.” Paper presented at the EEA Conference, New York, February 24–27, 2011.

Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Scott, James C. 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 1985. Commodities and Capabilities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 1988. “The Concept of Development.” In Handbooks of Development Economics Vol. 1, edited by J. Behram and T. N. Srinivasan, 2–23. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Sen, Amartya. 1993. “Capability and Well-Being.” In The Quality of Life, edited by Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen, 30–53. New York: Oxford Clarendon Press.

Sen, Amartya. 2000. Development as Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 2003. “Development as Capability Expansion.” In Readings in Human Development, edited by Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Shiva Kumar, 3–16. New York: Oxford University Press. Originally published in Journal of Development Planning 19: 41–58.

Sultana, Nasrin, and Alema Karim. 2005. “Women in Bangladesh: A Journey in Stages.” In Female Well-Being: Toward a Global Theory of Societal Change, edited by Janet Mancini Billson and Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, 67–93. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Sumner, Andrew, and Michael Tribe. 2008. International Development Studies. Theories and Methods in Research and Practice. London: Sage Publications.

Tilly, Charles. 1998. Durable Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Townsend, Peter. 1979. Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living. London: Penguin Books and Allan Lane.

WeD. 2008. “Well-being Indicators. Measuring What Matters Most.” ESRC Briefing Paper 2/08. Bath. UK: University of Bath.

Wilkinson, Richard and Kate Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Penguin Books.

Woolcock, Michael, and Deepa Narayan. 2000. “Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory, Research, and Policy.” World Bank Research Observer 15: 225–249.