7 Governance, Poverty and Social Justice

in the Coastal Fisheries of India

7.1 INTRODUCTION

Coastal fisheries in the South are often equated with material poverty (Thorpe et al. 2007; Daw et al. 2009; Béné et al. 2010). This particular category of primary livelihood activities, which provides direct employment to more than 30 million people (FAO 2009) and indirect employment to many tens of millions more, currently faces substantial ecological crises (Pauly et al. 1998; Worm et al. 2006). Ecological degradation is supposed to be one of the causes of poverty in the sector; an opposite vision suggests, however, that because of the open access nature of the resource, it is the already poor who seek out fishing for a hand-to-mouth existence (Jentoft and Eide 2011). Whatever one's views on this matter, many in the fisheries field agree with Béné (2003:968) that especially “small-scale fisheries should… be at the core of [poverty alleviation] research.”

However, material poverty is not all there is to fishing. Bavinck (2011) notes that a century of industrialization and globalization has created very substantial economic wealth in the fisheries of the South, with more potentially lying ahead (World Bank 2008). These riches are not, however, distributed equally. One of the most obvious dividing lines is between small-scale and large-scale fishers (Platteau 1989), with the former generally enjoying the lesser part of the deal. Not only do small-scale fishers catch less than large-scale fishers do; they often suffer badly from the latter's encroachments into what they perceive to be ‘their’ coastal waters. Rather than reflecting material want alone, poverty in fisheries can therefore be linked to problems of social justice (Bavinck and Johnson 2008).

This chapter is about the governance of medium-level conflicts between large-scale and small-scale fishers in India, in the context of skewed distributions of poverty and wealth. Governance in this context is defined as “administration of access to and provision of rights, services and goods” (Benda-Beckmann et al. 2009:2). In line with contemporary practice (Kooiman et al. 2005), governance is understood to take place at different scale levels, from local to international, and includes a variety of actors belonging to state, market and civil society. In many cases it is characterized by legal pluralism, or a condition in which “different legal mechanisms [are] applicable to identical situations” (Vanderlinden 1971:20). As large-scale and small-scale fishers often disagree fundamentally about what is fair and right fishing practice, state authorities are often called upon to mediate. This is in itself a tricky affair. But what happens when state authorities too are divided by administrative boundaries? The ongoing fishing war between large-scale and small-scale fishers in two adjoining states of southeast India provides a case in point. One party to the conflict consists of rural small-scale fishers, utilizing technology that is low-range, beach-based, and capital-extensive (Johnson 2006). Such fishers inhabit communities that frequently boast strong institutions for addressing a variety of internal and external problems. In the coastal fisheries of South India, caste councils, otherwise known as uur panchayats,1 are in charge of governance. These uur panchayats exert a claim to inshore sea territory and make rules to regulate fishing (Bavinck 2001). The rules decided upon are meant to preserve fish stocks for future use, and ensure fairness within communities but also with regard to outside fishers (Bavinck and Karunaharan 2006). The other party to the conflict consists of a new class of entrepreneurs that emerged from the Blue Revolution initiated in the post-WWII period for the purpose of increasing the productivity of fishing. Trawler fleets based in newly constructed fishing ports constitute its backbone. The businessmen who have taken up this new métier have often developed their own understandings of fisheries law and governance. In the fishing ports of India, trawler-owner associations have not only created distinct sets of rules but also run their own courts (Bavinck 2001).

With marine resources and fisheries being concentrated in inshore zones, many trawl fishers in India have come into conflict with small-scale fishers already working in these regions. Governments are the third party to fisheries governance. In many nations, fisheries law is frequently of recent origin, and relatively underdeveloped. As we shall also see in the case study presented in this chapter, government efforts frequently still focus on conflict management, rather than on resource conservation. Such action bears fruit if the conflict at hand takes place within the government's area of jurisdiction. But sometimes fisheries conflicts transcend administrative boundaries and are transferred to higher scale levels. This is the case in the low-intensity fishing war between fishers in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, which commenced in the early 1990s and continues until the present. The following section (7.2) sketches the contours of this fishing war in the context of the human geography of the Coromandel Coast. Section 7.3 describes the history of the Tamil Nadu-Andhra Pradesh fishing conflicts, after which section 7.4 zooms in on a detailed account of the hostilities in October 1995. Section 7.5 follows with an overview of the continuing hostilities from 1996 until 2008. Section 7.6 then applies a legal pluralism perspective to the analysis of the fishing conflict. This analysis is instructive in formulating the implications for governance at multiple levels of scale, as well as for poverty reduction and social justice in section 7.7. Finally, section 7.8 concludes. The chapter is rooted in two years of intensive field research (1994–1996), followed by yearly research visits continuing to date, on the topic of fisheries conflict, law and management in various locations in northern Tamil Nadu. The research combined qualitative and quantitative data, including daily records of five trawler unit activities, in-depth interviews with fishers, fisher leaders and government officials in Chennai and Tamil Nadu.

7.2 FISHERIES OF THE COROMANDEL COAST

Characteristics of the Region

In the British colonial era, the Madras Presidency subsumed most of what later became the states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. The stretch of coast between Point Calimere in the south and the mouth of the Krishna River in the north—a distance of about 700 kilometers—was generally known as the Coromandel Coast. The fisheries of this shoreline have struck observers because of their singular uniformity. Hornell (1927:60) was the first to note the similarity of fishing technology, which he explains by reference to the character of the natural environment. Over most of its length, the Coromandel Coast consists of surf-beaten beaches, uninterrupted by natural harbors or sudden changes of terrain. The fishers make use of a small and ideally suited craft called kattumaram to exploit available fish stocks.

According to Indian standards, the fishing grounds of the Coromandel Coast are relatively poor, with an exception for the areas around occasional river mouths. Most stocks, which include shrimp and a large number of fish species, are concentrated in the inshore belt, up to a depth of fifty meters. The small-scale fishing population of this region is both ancient and numerous. In its Tamil Nadu section alone, the Coromandel Coast hosts 296,116 people of fishing origin. These fisherfolk inhabit 237 marine fishing hamlets, one for an average of 1.7 kilometers of strand. The Andhra section of the Coromandel Coast contains 184 fishing hamlets, with a population of 127,553 (CMFRI 2005).2

The similarity of environmental circumstances and fishing technology is complemented by social homogeneity. In Tamil Nadu, the Pattinavar caste predominates among fishers. In Andhra, it is the Pattapu, who are recognized as being of Tamil origin and closely related to the Pattinavar. Thus, according to Vivekanandan et al. (1997:79), the Pattapu fishers of southern Andhra “continue to interact with their caste brotherhood on the other side of the border.” The description these authors provide of Pattapu political and social structure is reminiscent of the situation I found in Tamil Nadu. Economically speaking, Salagrama (2006) categorizes most rural fishers along the east coast of India as neither ‘very well off’ nor ‘destitute’. Bavinck (2001:86), who made an in-depth study of one particular fishing village south of Chennai, confirms that: “the majority of fishing households stand in between these two extremes [and…] have enough gear to maintain a reasonable standard of living.” However, approximately 15 percent of village households enjoy no more than a hand-to-mouth existence.

Governance Structure

The Madras Presidency fell apart in 1953 and linguistic divisions decided the borders of the new states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. These happened to separate the fishers of the larger Coromandel Coast into two. Henceforth, both populations oriented themselves to different sources of governmental law, policy and administration. India is a constitutional republic consisting of twenty-five states and seven so-called union territories. Each state maintains a substantial degree of control over its own affairs. The precise division of responsibilities between the union government and the various state governments is delineated in a schedule appended to the constitution. According to this schedule, state governments enjoy responsibility for fisheries within territorial waters, up to twelve nautical miles from shore. The union government, on the other hand, deals with fishing activities beyond this limit.

Matters dealt with by state governments in India frequently have repercussions on the affairs of neighboring states. The conflicts about river water in southern India are notorious, pitching the Tamil Nadu government against the governments of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Significantly, there is no ready-made platform for problems of this nature, which have to be addressed through arduous bilateral negotiations. Fisher conflicts are probably one of the smaller issues afflicting relations between Indian states. In principle, it must be noted, there is no official rule prohibiting Tamil Nadu fishers from fishing in Andhra Pradesh waters; in fact, the constitution provides for mobility of citizens from one state to another. A special difficulty in the case of fishing conflicts is that Andhra Pradesh—at least in the 1990s—lacked appropriate legislation. The Tamil Nadu government enacted a law to prohibit trawl fishing within a three-nautical-mile coastal zone in 1983. The government of Andhra Pradesh passed a similar piece of legislation in 1994, restricting trawl fishers to a zone beyond four nautical miles. As we shall see below, neither of these restrictions is enforced, however.

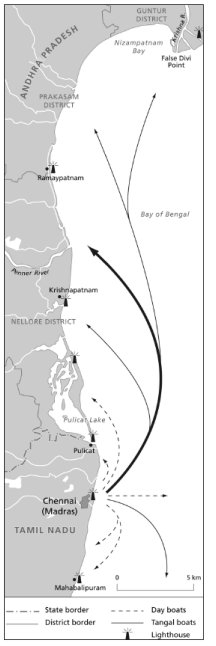

Map 7.1 Andrah Pradesh Fishing Grounds

Source: University of Amsterdam, Map Makers (2011).

Blue Revolution

The administrative reordering of South India coincided with the start of a comprehensive government fisheries programme, the results of which became known as the blue revolution. In the 1950s, the union government of India and many state governments adopted the advice of international agencies to radically modernize marine fisheries and increase production. Rather than building upon the accomplishments of small-scale fishing, the approach was to try to implant a totally new fishing sector. The introduction of relatively small motorized trawling vessels, locally known as mechanized boats, constituted the programme's core. Such vessels could no longer be beach-landed. To safeguard their investments and make optimal use of markets, trawl fishers therefore congregated around newly developed harbor facilities. The most important landing center along the old-time Coromandel Coast was Chennai (formerly known as Madras), the capital of the state of Tamil Nadu. Chennai is located only sixty kilometers from the border of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, and its fishing harbor berths approximately seven hundred vessels. In southern Andhra Pradesh, only one medium-size fishing port developed. Until the late 1980s the trawl fishers of Chennai generally stayed in Tamil Nadu waters, although seasonal migration to Andhra waters did take place. Technological features constituted the main barrier. With craft generally no longer than thirty-two feet, and preservation techniques practically unavailable, trawl fishers could go for day-fishing trips only. It was only with the increasing size of trawlers and the introduction of cold storage—both of which events took place around 1990—that longer trips became possible. From then on, most trawl fishers from Chennai started traveling north, to what they considered to be the richer fishing grounds of southern Andhra. Making fishing trips of one week to ten days, trawlers ventured right up to the mouth of the Krishna river, at about 350 kilometers distance. Most of them, however, proceeded no further than Ramaypatnam and the mouth of the Penner river (see Map 7.1). More recently, however, trawl fishers have also been exploring fishing grounds further north. The trawl fisheries of South India are far more stratified than the small-scale fisheries are. The production process centers on the trawler owner, who generally does not go to sea but manages operations from shore. A skipper is in charge of fishing activities. He is supported by a crew of five to six. Shore operations are taken care of by an irregular group of generally ill-paid workers.

Table 7.1 Interception of Chennai Trawlers in Andhra Waters 1993–1995

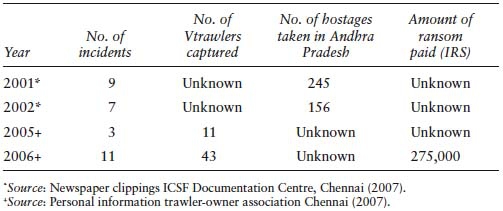

Table 7.2 Interception of Chennai Trawlers in Andhra Waters 2001–2006

7.3 THE HISTORY OF TAMIL NADU-ANDHRA PRADESH FISHING CONFLICTS

At the root of most fishing wars are disagreements about rights: Who has the right to fish where, when and how, and who is excluded from fishing? Serious conflicts between trawl fishers of Chennai and small-scale fishers in southern Andhra emerged when the former increased their radius of action. Concentrating their fishing operations in the inshore zone, the former regularly damage small-scale fishers’ gear and endanger lives. In addition, small-scale fishers hotly dispute the legitimacy of trawl fishers’ operations in inshore Andhra waters. The small-scale fishers of Andhra Pradesh respond to encroachments by capturing trawlers and holding crews for ransom. Trawl fishers sometimes retaliate in kind. Table 7.1 presents data on hostilities as they were recorded for the period 1993 to 1995.

Fourteen major incidents took place in 1993 and 1994 alone. A similar number occurred in 1995. Smaller incidents involving only one or two trawlers and a quick and quiet settlement are not included in this overview as they are frequently not reported. As it is, most trawler owners and workers in Chennai have been involved in some such events at some point in time. Some have had their trawlers seized several times in a row. Each time they lost not only the ransom amount, which averages Rs 15,000 to Rs 25,000 (then conversion rates US$ 375–625), but also equipment, fuel and the catches in their holds too. Table 7.2 presents information on larger incidents in the period 2001 to 2006, the main intention being to convince the reader that the fishing war continues. As is the case for the earlier period, smaller incidents are not included. Note that there is no information available for this period on the number of hostages taken in Tamil Nadu; instead, information on the ransom paid is included.

In section 7.5, we will highlight some changes in the way the fishing war is conducted and resolved, as triggered by the advent of new technology and management approaches. For the time being, however, it is worth emphasizing that, both for outside observers as for participants, the incidents occurring in Andhra waters over a twenty-year period share similar characteristics. First of all, incidents all focus on marine resources and/or the damages caused to fisher lives or implements. A second common feature is that they pit large- against small-scale fishers. Third, all of the incidents entail a substantial measure of coercion and physical violence. And finally, incidents may be analyzed as possessing a similar structure or phasing. The similarity of features makes it worthwhile to consider one particular incident in more depth: the serious clash which took place in October 1995.

7.4 THE HOSTILITIES OF OCTOBER 1995

There are differences between observers with regard to figures and the precise sequence of events in October 1995, which we were never completely able to iron out. The basic story, however, is as follows. On October 17, 1995, the Tamil daily Katiravan, which is published in Chennai, included this brief report.3

Andhra Fishers Attack

[Trawl] fishers from Kasimedu, Chennai, were trawling in the surroundings of Kadappaanam in Andhra Pradesh. At one point the nets set by Andhra fishers were caught in the [propellers of] the boats and torn. Because of this, the Andhra fishers—who were heavily frustrated, saying “They come to our waters to catch fish, and now are damaging our nets”—appear to have attacked. When trawl fishers retaliated, two people were severely wounded. The Andhra fishers captured two trawlers and 102 Kasimedu fishers. Some trawl fishers escaped to Chennai, bringing 17 Andhra fishers with them. Policemen, having been informed of the incident, took the Andhra fishers to the North Beach police station. Three persons were taken to Stanley Hospital for treatment. The trawler owners’ association [of Chennai] sent a message to the Minister of Fisheries, D. Jeyakumar, to inform him of the incident. On behalf of the Minister, a delegation of fishers, headed by the fisher leader of Chennai-Chingleput District, P.Kuppan, went to meet the collector of Nellore District [in Andhra Pradesh], in order to obtain the release of the Kasimedu fishers.

According to this newspaper account, the hostilities on this particular day had three distinct moments. The first phase consisted of a scuffle between groups of trawler fishers and small-scale fishers at sea, following the supposed damage of fishing gear. The dispute went into a second phase when the two parties returned to their respective bases in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, taking along hostages and fishing gear. The last phase consisted of an extension to various state departments and even ministers. We will consider these three phases in detail below, taking along the occasional comments of participants and eyewitnesses.

Phase 1: Conflict at Sea

According to a skipper named Subramaniam, who was directly involved, the battle commenced in the night of 13 and 14 October off the coast of a fishing hamlet called Bangarapalayam in Nellore District. Subramaniam had been trawling at seventy fathoms depth when another trawler suddenly drew near. Subramaniam realized that this trawler had been hijacked and put on speed, but a group of irate small-scale fishers managed to jump aboard and tie up his crew of five. In the course of the attack, however, one of the assailants hurt his leg very badly, and his associates were eager to get him to the hospital quickly. When the engine of the other boat stalled, the assailants, believing that this had been done on purpose, tied a noose around one of the trawl fisher's neck and pulled him up and down. At that very moment Subramanian decided to take his chances, and set sail for Chennai and its fishing port, locally known as Kasimedu.

Subramaniam's story bears no clue to the reason for small-scale fishers’ fury. Informants from the trawl sector ventured various opinions, some saying that a trawler had indeed damaged some nets of local fishers, whereas others argued that there had been no provocation at all. According to latter voices, the small-scale fishers were mainly trying to collect money in order to meet the costs of the oncoming Diwali4 celebrations.

It seems that the small-scale fishers involved in this incident all derived from one particular fishing village, close to Kavaali in Nellore District. From descriptions, and from knowledge about the usual course of such attacks, it is likely that they used motorized small-scale craft to capture a single trawler—perhaps the offender, or another trawler which was easier to detain. This first trawler would then have been used to capture other boats, one after the other. In these circumstances, being in the vicinity is enough to risk detention. This could have been the case with Subramaniam, who argued emphatically that he was fishing at quite some miles from shore.

The brawl at sea was decided by a battle of force. The band of small-scale fishers had armed themselves with sticks and knives, and some trawl crews may also have brought along some items of weaponry. Even if this were not the case, crew members have no lack of implements which can be utilized for defense. The severity of the clash at sea is brought out in Subramaniam's account of the incident, the most bloodcurdling aspect of which is the trawl worker who was hung from a noose (the man did survive). According to the newspaper article quoted above, two persons were seriously wounded in the scuffle. This proved to be inaccurate. One Andhra fisher died, and several fishers from both sides needed hospital treatment.

Before moving on to the events in Phase 2, it is worthwhile taking a moment to consider why Subramaniam retreated from the brawl, leaving one of his workers behind. Asked this question, he said that he had weighed the risks. As an experienced skipper, Subramaniam was aware of the fact that hijacked trawlers are frequently stripped bare. Equipment, engine parts, content of the hold—everything is taken. The trawler he was responsible for was actually one of the finest in Chennai, and he himself had the reputation of being an exceptionally good skipper. It was also the only boat to have been fitted with an echo sounder—a very expensive piece of equipment which had been imported specially from Singapore. Besides his concern about losing this equipment, Subramaniam also expressed fear for his crew, who might again be captured. He also said that by staying around he also would have risked losing the seven Andhra fishers whom he himself had been able to take hostage.

Phase 2: Hostages and Appropriated Equipment

After the battle was fought, both parties returned to their bases, taking as many hostages and as large a quantity of fishing equipment with them as possible. Thus the small-scale fishers of Bangarapalayam returned home with fourteen trawlers and 102 trawl-fisher hostages. The latter were immediately confined in the village school and put under guard. Two trawlers, including the one skippered by Subramaniam, had managed to escape from the battleground. They took with them a total of seventeen assailants, who were to serve as hostages on the Chennai side. When the trawlers entered Kasimedu harbor on October 15 evening, a crowd jeered and threw stones and bottles at the prisoners, injuring some of them very badly. One of the trawler owners then apparently informed the police, who transferred the hostages to the police station. The wounded were taken to a local hospital for treatment. Why the hostages and the equipment? Aside from the things which assailants would immediately remove from the boats—notably the catch—and which would count as immediate profit, the main goal on both sides was to amass sufficient goods for the financial negotiations which all parties knew would follow.

Phase 3: Negotiation and the Exchange of Hostages

When frictions between Chennai and Andhra fishers started to exacerbate in the early 1990s, the governments of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh took steps to facilitate the resolution process. In 1993 they announced a framework, which consisted of peacekeeping committees, one at the district level and the other at the state level. According to this setup, interstate fishing conflicts would initially be negotiated by a district-level peacekeeping committee (with senior civil servants from the districts of Nellore and Chennai-Chingleput). More serious conflicts would be dealt with by a state-level committee.

Although this peacekeeping system had been installed by government order only two years earlier, fisheries department officers of Tamil Nadu admitted in 1995 that it was not functioning as it should. An assistant director of fisheries explained:

The point is that trawler owners are in a hurry. They are extremely anxious about their property, more than about the lives of the crew members who have been taken hostage. They also happen to have a good connection with the Minister of Fisheries. So, once they receive word of an incident, what happens is that they immediately phone the Minister who instructs the Department to depute someone to Andhra as soon as possible [bypassing the district peacekeeping committee]. (Interview Jeyaraj, November 5, 1

This is indeed what took place. Hearing that their boats had been captured, the fourteen trawler owners quickly called upon Kuppan, the leader of the trawler-owner association in Chennai. Kuppan immediately rang up the minister of fisheries, who made sure that a senior civil servant, a retired assistant director by the name of Vijayakumar, would accompany him to Andhra at once. The delegation, which left the same night, consisted of Kuppan, Vijayakumar and a number of affected owners. They proceeded to the capital of Nellore District, in which Bangarapalayam is situated, and met the district collector and the head of police. The latter acted as interlocutor with the fishers of Bangarapalayam.

The Tamil Nadu delegation phoned the fisheries department in Chennai on October 16 to let the home front know that no agreement had yet been achieved. The delegation had not even been allowed to enter Bangarapalayam yet. In the meantime, no trawl fishers dared set sail for Andhra waters and the Chennai fishing harbor was crowded with vessels.

On October 21, the Tamil newspaper Dinamalar reported that groups of Chennai fishers had staged a roadblock to demand more effective government action. On October 22, the same paper noted that the commissioner of fisheries, the highest civil servant in the Tamil Nadu Fisheries Department, had joined negotiations, along with a subcommissioner of police. Later that day, news of a settlement reached Chennai, the details of which gradually emerged. The Chennai delegation had negotiated a ransom amount of Rs 250,000 (then US$ 6,250) for the boats and hostages. According to my informants, the amount was made up a follows: Rs 100,000 for the family of the Andhra fisher who had died, Rs 50,000 for a fisher whose leg had to be amputated, and Rs 100,000 as compensations for damaged fishing gear. The whole amount was to be handed over to the collector of Nellore District, who would remit it to the uur panchayat leaders. The hostages were to be exchanged some days later at the Andhra Pradesh-Tamil Nadu border.

Eight days after the incident, the official ritual of exchange occurred at a place called Tadaa, close to the border town Gumudipundi. The ransom amount had already been transferred. In the presence of high officials of the Tamil Nadu Fisheries Department and the Nellore District Revenue Department, the two groups of hostages crossed the border in opposite directions, to return home. For most people, the case was now closed. Trawl fishing in Andhra waters recommenced, and officials soon returned to their normal duties.

The incident did have a sequel, however. Thus the trawler-owner association of Chennai tried to recover at least part of the ransom amount from the two trawler owners whose crews had taken Andhra Pradesh fishers hostage. After all, it was in the preceding fights that an Andhra fisherman had been killed and another seriously injured. If this had not transpired, the association leaders reasoned, the ransom would have been less. Subramaniam's boss, however, who belonged to a rival trawler-owner faction, refused to pay. This triggered a long-drawn-out game of cat and mouse between him and the association.

Secondly, rumors reached Chennai that the officials on Andhra side had pocketed a large percentage of the money, and that a fight had taken place between small-scale fishers in Bangarapalayam about the division of proceeds. One man had reputedly been killed. Rumors about financial misappropriations by leaders of the trawler-owner association also continued to circulate.

7.5 HOSTILITIES IN THE PERIOD 1996–2008

The latest evidence of hostilities between trawler fishers from Tamil Nadu and small-scale fishers in southern Andhra dates back to 2008. In February 2007 I was able to interview a skipper in Chennai who had just been hijacked, as well as a few representatives of the trawler-owner association and the fisheries department about this and other incidents. These discussions emphasized what we have noted already above, namely the persistence of conflict over the years. Trawler owners and crew members in Chennai were as perturbed about the situation as they had been twelve years earlier. It was clear from the viewpoint of trawl fishers that the problem remained as urgent as it had been before.

Some remarkable changes have occurred in the interval, however, in the manner by which conflicts are acted out. A first set of changes follows from the telecom revolution in India; the second is a consequence what could be called innovations in human resource management. All trawl vessels plying the inshore waters of India are now equipped with mobile phones, which allow the crew to communicate with the shore. The same is true of previously remote villages along the Coromandel Coast of Andhra Pradesh, which are suddenly within calling distance of Chennai. The availability of communication facilities has impacted the conflict between trawl fishers and small-scale fishers in various ways. First of all, it allows for individual members of either party to alert their colleagues about an impending attack. Trawl fishers often also have the additional advantage of GPS, which allows them to transmit their geographical positions exactly. For the attacking party, speed and alacrity have therefore become more important: the quicker a boat is captured, the less chance there is that the crew has made a call.

Secondly, cell phones make it easier for the trawl crew, and the attacking party, to contact the owner. Whereas in 1995 trawler owners were often unaware of the capture of their trawler many days after the event had taken place (and consequently worried a great deal about the possibility), ten years later they could be alerted immediately. Although the vessels were generally still taken to shore and the crew members held hostage until ransom had been paid, the entire process (Phases 1 to 3) became much abbreviated. For owners, who believe that time is money, this is of advantage, also because there is an increased chance of the boat being released without additional damages.

Finally cell phones finally have made it possible to involve governmental authorities more rapidly in the negotiation process. Whether this has resulted in increasing levels of governmental participation is questionable, however. The telecom revolution actually seems to have had more of an opposite effect: trawler owners negotiating quickly and efficiently with the hijackers to achieve a release, and government agencies left out of negotiations altogether.

Trawl fishers have also been inventive in their management strategies. In the mid-1990s, trawler crews were entirely made up of Tamil speakers. This proved to be a severe disadvantage in the case of hijacking. Although Tamil and Telugu are related languages, they are sufficiently dissimilar to impede communications. By employing one or two Telugu speakers on board their vessels, trawler owners have now gained the ability to talk to their attackers. This shift appears to correlate with a change in the way hijackings are countered: rather than equipping their crews with weapons, as occurred in 1995, trawler owners now aim at smoothening the path for a quick release.

There are more indications that trawl fishers have become more resigned to the incidence of conflict. Trawler owners, for example, now regularly appear to provide their skippers with a substantial sum of cash, with which they are able to pay off hijackers immediately. Moreover, at least one of the trawler owner associations in Chennai now runs a mutual insurance scheme, by which its members can reduce the costs of potential hijackings.

7.6 ANALYSIS FROM A LEGAL PLURALISM PERSPECTIVE

Scale is a core issue in this type of research. Why do localized disputes between fishers of two states develop into violent clashes, mobilizing senior officials and politicians on both sides and culminating in an exchange of hostages at the state border?

The Dynamics of Fisheries from a Legal Pluralist Perspective

One of the fishing war's core features is that it involves two occupational categories—small-scale and trawler fishers. Disputes between them have occurred all along the Coromandel Coast ever since trawlers were first introduced in the 1960s, and it is worthwhile to consider their dynamics in more detail. My analysis of Tamil Nadu fisheries (Bavinck 2001) suggests that small-scale and trawl fishing are based on contradictory principles. The rule system of small-scale fishers is predicated on the recognition of preferential fishing territories. These territories are bounded on two sides by a seaward extension of each village's self-determined land borders. On the side of the open ocean, boundaries are fluid and generally related to the area in which fishing is conducted. Village regulations pertain especially to fishing gear. Thus, uur panchayats sometimes ban the usage of deleterious gear types, or regulate their applications.

The principles of trawl fishing are quite different. Other than small-scale fishers who carry out most of their fishing operations in the proximity of their landing centers, trawl fishers have a large geographical range. Utilizing active fishing gear, they seek out target species where they are to be found, and move from one place to the next. As noted above, however, the largest densities of biomass are found in the inshore belt, which is claimed by small-scale fishers. Rather than asserting rights to an own fishing territory, trawl fishers have therefore been more interested in denying the preferential rights of small-scale fishers. There is evidence that in the early period of trawl fishing, uur panchayats throughout Tamil Nadu tried to ban trawling in their waters. However, these attempts failed for two reasons. First, trawl fishers denied uur panchayats’ authority over their operations. Second, the trawl fishers possessed the technical means to ignore uur panchayats’ directives. The difference between these two statements is significant. For small-scale fishers aboard sail- or hand-powered craft, engine-powered trawlers can hardly be apprehended. It was only with the advent of outboard motors in the 1990s that their punitive capacities increased significantly (cf. Bavinck 1997).

Secondly, trawl fishers received powerful support from state governments. The government of Tamil Nadu—which had introduced trawlers in the first place—has tended to back up the trawler industry. Only after the small-scale fishers’ movement built up momentum and conflicts reached a peak did the state government finally take action to restrict trawling. The Tamil Nadu Marine Fishing Regulation Act of 1983 is hardly implemented, however, and relations between small-scale and trawl fishers remain uneasy.

Most contemporary disputes in Tamil Nadu appear to arise because a trawler has damaged small-scale fishing gear. Reactions vary. Some trawler crews are courteous, immediately reimbursing the small-scale fishers in cash or in kind. In many other cases, however, incidents develop characteristics of what I have elsewhere termed ‘forum-wresting’ (Bavinck 2001).5 The culprit crew tries to escape unseen, whereas the small-scale fishers are intent on arrest. If the small-scale fishers manage to apprehend the boat in question, it is conveyed to shore, where a trial is conducted by the uur panchayat. In this case, small-scale fishers hold the advantage—the trawler owner in question, fearing loss of income and damage to his property, is inclined to meet their financial demands. If, on the other hand, the trawler crew manages to escape, small-scale fishers will have to apply to the trawler-owner court in Chennai. There, trawler fishers possess the advantage. The small-scale fishers will have to provide clear proof in court of the culprit and the damaged incurred, and reimbursements—if provided at all— are always lower than what would be obtained in the village trial.

As is the case in Andhra Pradesh waters, small-scale fishers in Tamil Nadu occasionally do apprehend whole groups of trawlers. Nowadays, however, this tends to happen only after serious incidents, such as with a loss of life. When this takes place, leaders of the trawler-owner association and government officers rush in to facilitate a settlement.

Government officers and trawl fishers in Tamil Nadu do not consider the mere act of fishing in village waters or damage to small-scale fishing gear sufficient reason for massive apprehensions. Small-scale fishers in the state also know that a onetime apprehension of a single boat, for reasons such as the damage of fishing gear, bears little risk of escalation. If this act is repeated a little too often, however, the trawler population may organize a violent retaliation.

Larger incidents also bear the risk of government involvement. During the mid-1990s, the trawler-owner association in Chennai was known to enjoy powerful political patronage.6 Trawler owners, moreover, also enjoyed what is locally known as ‘money-power’. Patronage and money-power are assets which small-scale fishers know are influential in moving government machinery. Their experience with the Tamil Nadu police force, which has a brutal reputation, is particularly bad. The official system of justice too is not much appreciated. Like poor and powerless people everywhere, small-scale fishers therefore prefer to keep the government at a distance. They consciously avoid actions, such as large-scale apprehensions of trawlers, which bear any risk of government involvement. In the course of their history, the conflicts between small-scale and trawl fishers along the northern coastline of Tamil Nadu have therefore abated.

The Andhra Pradesh-Tamil Nadu Fishing War Revisited

Having briefly considered the nature of the fishing industry, we can now return to the 1995 incident presented above. A few inferences can be made. The first is that fishers were the main parties to the conflict, and that the two state governments were drawn in only in a later stage. When they did come in, however, they appeared to be singularly ill-prepared. Not only did governmental agencies lack appropriate legislation; the mediatory structure, which they had put in place earlier, proved to be largely ineffective.

There is evidence that the parties to the 1995 incident actively sought to involve administrators in the conflict. Almost the first thing the trawl fishers of Chennai did after they heard of the clash was to inform the minister of fisheries and obtain his support. Thus civil servants came to play an important role in the negotiation process on the Tamil side. The roadblock carried out in Chennai later only increased pressure on the Tamil Nadu administration.

On the side of Andhra Pradesh, official action soon followed. After all, the Tamil delegation was making a beeline for district authorities in Andhra Pradesh, who were requested to play a mediating role. No evidence was found that the small-scale fishing party in Andhra solicited authorities’ assistance from the beginning. From the fact that the Andhra Pradesh government had regularly participated in the resolution of earlier fisheries crises, it is likely, however, that its involvement was not unexpected. Rather, it was probably part of the small-scale fishers’ expected scenario.

The 1995 conflict obviously revolved around the same issues which plague relations between the two fishing parties within states as well. There is evidence that small-scale fishers in southern Andhra Pradesh intensely dislike the Chennai fishers operating on their fishing grounds, particularly when such operations result in the destruction of fishing gear or the loss of life. Like their compeers on the other side of the border, uur panchayats in Andhra Pradesh like to maintain control over fishing in their sea territories, and regularly take matters into their hands. Boat capture is a prime method vis-à-vis the trawl fishers of Chennai.

The presence of an administrative divide, however, has an unusual effect as it cushions small-scale fishers from their antagonists. As noted above, small-scale fishers in Tamil Nadu frequently find state administrators allying with the trawl sector. This limits their reactions to perceived injustice. In an interstate conflict, however, administrators are much more on their side. This follows from patriotic fervor, as well as from administrative rationale. State-level politicians use administrative resources to maintain their vote banks (de Wit 1996), and it makes political sense for administrators involved in the resolution of a conflict to act on behalf of ‘their’ fisher voters. Additionally, administrators on both sides are said to skim off a part of the financial proceeds of any settlement. Senior officials in the Tamil Nadu Fisheries Department who had been involved in Andhra Pradesh-Tamil Nadu conflicts confirmed the inclination to support the own fishing population, in right and in wrong. Assistant director Jeyaraj: “If I accompany boat owners to Andhra, I act as their advocate, even if I know that they have made mistakes. I defend them and speak on their behalf” (interview November 5, 1995). The official who pointed this out also made clear that he thought an alliance with the own fishers was somewhat absurd. And, of course, he also identified professionally with colleagues on the other side of the border. The pressure to take sides, however, was severe.

How does the existence of an administrative buffer affect the course of a dispute? Further fieldwork on the strategy of uur panchayats in Andhra Pradesh is, however, necessary before making at a final judgment. It is reasonable to assume that small-scale fishers in Andhra Pradesh enjoy more freedom in determining their strategy than those of Tamil Nadu. Rather than settling for the capture of a single vessel—which is generally what fishers in Tamil Nadu do—they can increase the scale of retaliatory action. Moreover, they need to worry less about motives. The rumor amongst Chennai fishers that small-scale fishers in Andhra were capturing boats only to meet the costs of oncoming religious celebrations may therefore well bear at least a grain of truth.

7.7 IMPLICATIONS FOR MULTILEVEL GOVERNANCE

What implications does this somewhat unusual case study have for legal pluralist thought? First of all, it reconfirms that the state cannot be assumed to always be the dominant party in a societal configuration (Merry 1988; Bavinck 2001). Conflicts which take place in the fisheries sector of India are generally fought out by the fishers themselves, in terms of fisher law. The state is often no more than a marginal player in these confrontations. Fishers and their organizations, however, find certain kinds of disputes more difficult to handle than others. Such is the case with conflicts between small-scale and trawl fishers. Disputes of this kind regularly emerge into the public arena, where state officials are called into adjudicate (Bavinck 1998).

The case study then draws our attention to the functions of administrative divides. A boundary, such as the one between Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, has special consequences for parties to a dispute. After all, borders demarcate the existence of administrative and political realms, and a fissure between them. Such interstices create difficulties as well as opportunities for all parties and individuals concerned. The inconveniences are clear. There is no common administrative and political unit to appeal to when problems—such as a dispute about fishing rights—run out of hand. This troubles fishers on both sides of the border. But it also causes headaches to the administrators and politicians concerned. Peacemaking procedures have to be improvised, tempers flare, and outcomes are highly uncertain.

At the same time, administrative boundaries also generate special opportunities. Thus small-scale fishers in Andhra Pradesh do not face a powerful alliance of trawl fishers and civil servants. As a consequence, it was argued that the conflict is allowed to escalate to warlike proportions. The negotiations which follow have more positive results than would be the case in an intrastate conflict. Here again, the fact that state governments support ‘their’ fishers against others plays a decisive role.

For trawl fishers in Tamil Nadu operating across the border, the state boundary has mixed effects. On the one hand, it helps to shield their fishing activities in the adjacent inshore zone. After all, small-scale fishers from Andhra Pradesh have no political leverage in Tamil Nadu, and cannot exert control over trawl fishing. For the trawl fishers who are captured at sea, however, the boundary has enormous disadvantages as their assailants are sheltered and can do as they please. Financial risks increase disproportionately.

7.8 CONCLUSION

This chapter started with an allusion to the equation between coastal fisheries and poverty. Having extensively discussed the war that has been taking place between fishers of two neighboring states for two decades now, it is therefore worthwhile reflecting on the role poverty plays. A few points emerge. A first observation is that poverty is available not among one but among both parties. In fact, as Salagrama (2006) points out, there is significant and perhaps more extreme poverty in the urban fisheries of India than in fishing villages where social safety nets are still commonplace (Kurien 1995). Although crew members aboard trawlers are not among the poorest of the urban working class, their livelihood positions are much weaker than that of trawler owners. Moreover, these crew members depend on owners for crucial operational decisions such as sending vessels to the inshore zone of Andhra. Although owners certainly run the risk of losing money, crew members face substantial physical danger too. Vulnerability being an important dimension of poverty (cf. Pouw and Baud, this volume), these workers are ‘poor’ in more ways than one. This is true for small-scale rural fishers as well. Catching less, and having less access to profitable markets, such fishers and their families generally belong to lower income categories, with a segment being categorized as ‘very poor’. Small-scale fishers' capital is generally tied up in fishing equipment, which runs risk of damage from the activities of trawlers plying the inshore zone. Like the crew members on trawlers, these men suffer significant physical dangers at sea. But their poverty is also of a comparative kind: aware of the catches made by trawl vessels and the riches they represent, small-scale fishers together feel unfairly poor.

Crucial to the discussion on ways forward is the level at which governance activity should be undertaken. In the case of the Andhra-Tamil Nadu fishing wars, which involve moving resources and fishers from a wide geographical area converging in different spatial locations, governance first of all needs to be flexible and adaptive (Armitage et al. 2007). It also needs to be responsive: an incident between fishers at sea requires immediate attention for it not to develop into a full-fledged battle.

Secondly, governance needs to be nested at various administrative scale levels (Ostrom 2007). Although local agencies (state and nonstate) are frequently incapable, by the scale of the problem at hand, to resolve a conflict on their own, their contribution is nonetheless of importance. After all, local fisher agencies on both sides take active roles in ‘organizing’ a skirmish if it takes place, and also play a part in its prevention. But such governance activities need to be embedded in regional and national governance. The latter is relevant because of the tendency of fishing wars to coincide with administrative divides, such as between Indian states. Although nesting is an important aspect, one must beware of always involving multiple governance levels. The principle of subsidiarity is in this context a useful one. Carozza (2005:38, note 1) provides a working definition: “Subsidiarity is the principle that each social and political group should help smaller or more local ones accomplish their respective ends without, however, arrogating those tasks to itself.” According to this principle, one would leave whatever problems fisher organizations, and other local governance institutions, can handle for them to resolve. It is only when problems exceed their capacities that higher-level institutions become involved.

This brings us to a third conclusion, which insists that governance requires pairing governmental and fisher agencies in a system termed ‘co-management’ (Wilson et al. 2003). Co-management refers generally to the sharing of rights and responsibilities by government and civil society (Armitage et al. 2007). Under conditions of legal pluralism, however, co-management is not an easy matter as it also implies the bridging of legal, cultural and social barriers between different groups. Therefore, as Jentoft et al. (2009:36) point out, under such conditions “co-management is a process that evolves over time and through an interactive process that requires participation of stakeholder groups and organizations and a proactive state.”

Finally, the resolution of regional fishing wars requires that governors go beyond the expressions of conflict to address their roots. Bavinck and Johnson (2008) have noted that “social justice and distribution issues have not been at the forefront in planning discussions with regard to capture fisheries in India, as they have been in agriculture.” These authors argue that, alongside the problem of ecological degradation which is occurring in fisheries, governments need to take urgent interest in problems of social justice, if only because fishing wars, like the series of conflicts occurring between fishers from Andhra and Tamil Nadu, are rooted in varying notions hereof. In the absence of such more fundamental action, regional fishing wars stand the chance of infinite prolongation.

NOTES

1. Other than the lowest tier of local government in India, which is called Gram Panchayat,uur panchayats have no relationship whatsoever with governmental administration, deriving their status from precolonial social structure (Mandelbaum 1970).

2. These figures have been calculated on the basis of district-level data. The Coromandel Coast of Tamil Nadu roughly coincides with the districts of Thiruvallur, Chennai, Kanchipuram, Villupuram, Cuddalore and Nagapattinam. In Andhra Pradesh, it corresponds with the districts of Nellore, Prakasam and Guntur.

3. Translation by the author.

4. Diwali is a major religious festival in South India.

5. ‘Forum-wresting’ bears analogies to the phenomenon Keebet von BendaBeckmann (1981) calls ‘forum-shopping’. The latter refers to the behavior of individual clients seeking out the legal forum which they believe will be most sympathetic to their cause. Forum-wresting is a characteristic of groups rather than of individuals using force to ensure that a certain ‘case’ will be tried in one particular forum and not in another.

6. In the period 1991 to 1996 the minister of fisheries of Tamil Nadu originated in the trawl-boat fishing area of Chennai. This was his political constituency.

REFERENCES

Armitage, Derek, Fikret Berkes and Nancy Doubleday, eds. 2007. Adaptive Co-Management—Collaboration, Learning, and Multi-Level Governance. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Bavinck, Maarten. 1997. “Changing Balance of Power at Sea, Motorization of Small-Scale Fishing Craft.” Economic and Political Weekly 32 (5): 198–200.

Bavinck, Maarten. 1998. “‘A Matter of Maintaining the Peace’—State Accommodation to Subordinate Legal Systems: The Case of Fisheries along the Coromandel Coast of Tamil Nadu, India.” Journal of Legal Pluralism 40: 151–170.

Bavinck, Maarten. 2001. Marine Resource Management: Conflict and Regulation in the Fisheries of the Coromandel Coast. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Bavinck, Maarten. 2011. “The Mega-Engineering of Ocean Fisheries: A Century of Expansion and Rapidly Closing Frontiers.” In Engineering Earth: The Impacts of Mega-Engineering Projects, edited by Stanley D. Brunn, 257–273. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer.

Bavinck, Maarten, and Derek Johnson. 2008. “Handling the Legacy of the Blue Revolution in India—Social Justice and Small-Scale Fisheries in a Negative Growth Scenario.” American Fisheries Society Symposium 49: 585–599.

Bavinck, Maarten, and K. Karunaharan. 2006. “A History of Nets and Bans: Restrictions on Technical Innovation along the Coromandel Coast of India.” Maritime Studies—MAST 5 (1): 45–59.

Benda-Beckmann, Keeba von. 1981. “Forum Shopping and Shopping Forums: Dispute Processing in a Minangkabau Village in West Sumatra.” Journal of Legal Pluralism 19: 117–159.

Benda-Beckmann, Franz von, Keeba von Benda-Beckmann and Julia Eckert, eds. 2009. Rules of Law and Laws of Ruling. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Béné, Christopher. 2003. “When Fishery Rhymes with Poverty: A First Step beyond the Old Paradigm on Poverty in Small-Scale Fisheries.” World Development 31 (6): 949–975.

Béné, Christopher, Bjørn Hersoug and Edward H. Allison. 2010. “Not by Rent Alone: Analysing the Pro-Poor Functions of Small-Scale Fisheries in Developing Countries.” Development Policy Review 28 (3): 325–358.

Carozza, P. G. 2005. “Subsidiarity as a Structural Principle of International Human Rights Law.” The American Journal of International Law 97 (1): 38–79.

CMFRI. 2005. “Marine Fisheries Census 2005.” Cochin, India: Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute.

Daw, Tim, Neil Adger and Katrina Brown. 2009. “Climate Change and Capture Fisheries: Potential Impacts, Adaptation and Mitigation.” In Climate Change Implications for Fisheries and Aquaculture, Overview of Current Scientific Knowledge, edited by Kevern Cochrane, Cassandre De Young, Doris Soto and Tarûb Bahri, 107–150. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 530. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

FAO. 2009. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2008. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

Hornell, James. 1927. The Fishing Methods of the Chennai Presidency. Chennai Fisheries Bulletin 18: 59–109.

Jentoft, S., M. Barinck, D.S. Johnson and K. T. Thomson. 2009. “Fisheries Comanagement and legal pluralism: how an analytial problem becomes an institutional one.” Human Organization 68: 27–38.

Jentoft, Svein, and Arne Eide, eds. 2011. Poverty Mosaics: Realities and Prospects in Small-Scale Fisheries. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Verlag.

Johnson, Derek. 2006. “Category, Narrative, and Value in the Governance of small-scale Fisheries.” Marine Policy 30: 747–756.

Kooiman, Jan, Maarten Bavinck, Svein Jentoft and Roger Pullin, eds. 2005. Fish for Life—Interactive Governance for Fisheries. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Kurien, John. 1995. “Income Spreading Mechanisms in Common Property Resource—Karanila System in Kerala's Fishery.” Economic and Political Weekly July 15: 1780–1785.

Mandelbaum, David G. 1970. Society in India. 2 volumes. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Merry, Sally E. 1988. “Legal Pluralism.” Law & Society Review 22 (5): 869–896.

Ostrom, Elinor. 2007. “A Diagnostic Approach for Going Beyond Panaceas.” PNAS 104 (39): 15181–15187.

Pauly, D., V. Christensen, J. Dalsgaard, R. Frasce, F, Jr. Torres. 1998. “Fishing Down Marine Food Webs.” Science 279: 860–863.

Platteau, Jean Phillipe. 1989. “The Dynamics of Fisheries Development in Developing Countries: A General Overview.” Development and Change 20 (4): 565–599.

Salagrama, Venkatesh. 2006. “Trends in Poverty and Livelihoods in coastal fishing Communities of Orissa State, India.” Fisheries Technical Paper 490. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

Thorpe, Andy, Neil L. Andrew and Edward H. Allison. 2007. “Fisheries and Poverty Reduction.” CAB Review: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources 2 (85): 12.

Vanderlinden, Jacques. 1971. “Le Pluralism Juridique: Essai de Synthèse.” In Le Pluralisme Juridique, edited by John Gilissen, 19–56. Brussels: L'Université Bruxelles.

Vivekanandan, V., C. M. Muralidharan and M. Subba Rao. 1997 (revised 2002). “A Study of the Marine Fisheries of Andhra Pradesh.” Unpublished report. The Hague: Bilance.

Wilson, Doug, Jesper Nielsen and Poul Degnbol, eds. 2003. The Fisheries Co-Management Experience: Accomplishments, Challenges and Prospects. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wit, Joop de. 1996. Poverty, Policy and Politics in Chennai Slums: Dynamics of Survival, Gender and Leadership. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

World Bank. 2008. “The Sunken Billions—the Economic Justification for Fisheries Reform.” Joint World Bank and FAO publication. Washington, DC: The World Bank and Food and Agriculture Organization.

Worm, Boris, Edward Barbier, Nicola Beaumont and J. Emmet Duffy. 2006. “Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services.” Science 314: 787–790.