11 Participatory Assessment of

Development in Africa

Poverty in Africa is predominantly rural. More than 70 percent of the continent's poor people live in rural areas and depend on agriculture for food and livelihood, yet development assistance to agriculture is decreasing. In Sub-Saharan Africa, more than 218 million people live in extreme poverty. The incidence of poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa is increasing faster than the population. Overall, the pace of poverty reduction in most of Africa has slowed since the 1970s (IFAD 2007).

11.1 INTRODUCTION

IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development) is one of many agencies worried about Africa's development prospects, and its lack of progress to improve its performance on many development indicators. There are many causes for Africa lagging behind. IFAD points at the multiple policy and institutional restraints imposed on poor people, with roots in precolonial, colonial and postcolonial governance deficits. It points at the flaws in policy theories behind World Bank structural adjustment programmes(SAPs). As a result of SAP, existing systems of service provision have been dismantled, without replacing them with new ones. The expectation was that private sector would step in. However, this only happened in the most promising areas, not in the marginal rural areas. These types of areas can be characterized by continuing stagnation, low productivity, low incomes and high vulnerability. Many small-scale enterprises in these marginal rural areas lack access to markets, and suffer from poor organization. Fluctuations in natural, economic and political environments, without adequate safety nets, often cause once promising initiatives to fail and built-up assets to be destroyed or to disappear again.

There is a long history of development interventions in the rural areas of Africa, either as standalone interventions or as part of integrated rural development programmes Many of these initiatives have been sponsored by foreign donors. During the 1980s and 1990s particularly, the Netherlands government had been actively supporting rural development initiatives in marginal areas in Africa: e.g., the Integrated Rural Development Programme in Western Province in Zambia, the District Programmes in Tanzania, the Arid and Semi-arid Lands Programmes in Kenya, Resource management in Kaya, Burkina Faso, and support to the Office du Niger in Mali (Sterkenburg and Van der Wiel 1999), to name just a few. Also, Dutch nongovernmental organizations have taken many initiatives in these and other rural areas in Africa, and in some of these areas Dutch-sponsored NGOs became the leading development agencies, for instance, in Northern Ghana (Dietz et al. 2002).

In the course of time the approaches to development projects became more sophisticated, with the use of logical frameworks in project design, the implementation of a process approach, incremental learning procedures, and an increase in monitoring and evaluation attempts during project implementation. If done well, it means the combination of baseline surveys, annual reports with (measured) progress and longitudinal analysis. The development industry is probably one of the most evaluated professional fields.1 Evaluations primarily involve project and programme assessments, and are undertaken by a host of consultants.2 More comprehensive evaluations assess the impacts of development interventions on particular sectors such as education or water supply and sanitation within a country or region, or of development approaches such as micro-finance.3

However, within the aid industry there are very few examples of long-term commitment to longitudinal approaches. Moreover, evaluations are often disappointing tools to learn about the linkages between long-term changes and ad hoc interventions. There are major difficulties in the attribution of cause (intervention) and effect (development or change). Contextual change is often more important than the intervention itself, but interactions between different events do not often get adequate attention. Furthermore, the quality of assessment depends on the quality of lowest-level data collection, and often there is lacking quality assurance at that level (political ‘cooking’ of data; just filling in forms). Dishonesty or corruption in project implementation is covered by nontransparent reporting or no reporting at all. Often there is a naive neglect of existing power structures in intervention regions and of existing geographical and cultural-institutional barriers between areas of intervention and higher-order regions. In an editorial for The Broker magazine (Bieckmann 2008:3) about the recent IOB evaluation of the Dutch Africa policy between 1998 and 2006, Frans Bieckmann wrote:

A different kind of evaluation is needed, one that includes a much more integrated analysis of national and regional dynamics… Analytical tools for this have yet to be developed… The picture that emerges is of a doctor who treats the patient's broken arm one year, a bad back the next, and later maybe a head injury. Never the whole body. Nor the environment in which the patient became ill. It is even less likely that the doctor entertains the possibility that he himself might have been the cause of the patient's recurring physical problems… Maybe next time the ‘patients’ themselves should be allowed to judge their doctor's treatment?

Most development-oriented evaluations are programme, project and organization specific. Programme or project evaluations focus on the degree to which the intervention's outcomes have been achieved (effectiveness) or on the efficiency or sustainability of the intervention's implementation. The starting point usually lies with the policy discourse behind the interventions, rather than with the underlying development frustrations locally. The relevance of the interventions to the target group's needs or development priorities is hardly addressed during evaluations. Confronted with programme or project outcomes not being achieved leads evaluators to attribute this failure to weak capabilities of the implementing organization, unruly circumstances or to the characteristics of target groups (which may easily result in blaming the victim). Therefore, certain recommendations of evaluation studies are implicitly based on the assumption that reality in the field refuses to adapt to policy. A scrutinization of the policy discourse itself is usually not part of the endeavor.

With the recent emphasis on sector-wide approaches, at the expense of integrated rural development programmes, evaluations tend to become even more focused on top-down, single-issue approaches to development, driven by central-level ministries and supported by donors withdrawing from field-level hands-on experiences.4 The rather sudden dismissal of integrated rural development programmes by donors and recipient governments went at the expense of productive sectors, in particular rural/agricultural development, and at the expense of marginal areas. It coincided with the so-called alignment and harmonization process (the Paris agenda: policy coherence for development —see Dietz et al. 2008), resulting in sector support and budget support to central governments. This often meant a restriction to social sectors like health care and education and to physical infrastructure like roads, dams and drinking water. This restriction was also stimulated by the attention for the Millennium Development Goals, with their meager attention for production, employment and income generation. The neoliberal belief in the strength of the market and in the private sector to take over is generally seen now as an illusion, a painful mistake, and the international aid agencies are slowly rediscovering the importance of strong state leadership (and public-private partnerships) in agricultural and rural development in Africa (World Bank 2008).

Robert Chambers has led the way in increasing the attention given to the poor in development and evaluation approaches.5 Evaluations have gradually shifted away from purely technocratic and expert-oriented activities towards stakeholder-inclusive and more participatory assessments.6 By the 1990s, participatory approaches had become accepted practice, at least on paper.7 But some observers questioned the rigor of the approach and the lack of attention paid to power structures. Also, the concept of ‘participatory evaluation’ became blurred. The same happened with the overarching concept of ‘participation.’8 Participatory impact evaluations are becoming a paradigm, but with different perspectives and experiences (Chambers et al. 2009). We position ourselves in the current shift from livelihoods to well-being approaches (Vaitilingam 2008) and the growing interest in deep democracy (Bieckmann 2008), and what these could mean for evaluation practice. By following Bebbington (1999), Leach et al. (1999) and Kabeer(2001), we aim to give hand and feet to the idea that what can be achieved in life is influenced by institutions, social capital and the level of empowerment. Local democracy, as pointed out by Deepa Narayan in Chapter 3 of this volume, is imperative in enabling people to satisfy their goals.

The epistemological and methodological implications of taking a participatory approach to impact assessment in this chapter are pointed out by means of two country case studies. The main research question underlying these two participatory impact assessments was to learn the nature and extent of the impact that development initiatives9 in the area under study have had on local people's livelihoods, in particular with regard to their poverty and well-being. Bebbington's (1999) typology of development capabilities was then used to operationalize this main question into digestible pieces of research. The research methodology thus evolving was a mixed-methods approach, combining both quantitative and qualitative research methods and techniques to bring out the experiences and perceptions of the local population in a critical-realist manner.

The first case study took place between 2000 and 2002 in the Pokot area in Kenya. The second case study is part of an ongoing research programme in northern Ghana and south Burkina Faso, and started in 2008;in this chapter we will highlight the results in an area called Sandema, in Upper East Region Ghana. Both the Kenyan and the Ghanaian case study regions experienced the presence of large, relatively long-lasting, multisector Dutch-sponsored development programmes: the Arid- and Semi-Arid Lands Development Programmes (ASAL 1981–1999)10 in Northwest Kenya and the rural development programmes of the Presbyterian Agricultural Stations in northeast Ghana, supported by ICCO, a large Dutch NGO with a Christian identity.11 In section 11.2, four well-integrated principles of participatory impact assessment are put forward as the guiding principles of the research methodology under construction. During the first stage of operationalizing the participatory approach, in Pokot, Kenya, the research methodology was field-tested with regard to the history of development initiatives, perceived changes in people's capabilities and attributed impact. The main findings and lessons learned are described in section 11.3. These were used to refine the methodology in the second phase of operationalization, in the Sandema area, in Ghana (and other areas in northern Ghana and south Burkina Faso), the results of which are discussed in section 11.4. In Section 11.5 a summary of key findings and insights in knowledge creation derived from the two case studies is provided. In the chapter conclusion, section 11.6, the relative weaknesses of participatory impact assessment are pointed out, as well as the current steps taken toward further strengthening this approach.

11.2 PARTICIPATORY ASSESSMENT PRINCIPLES AND OPERATIONALIZATION

A participatory approach to impact evaluation is best described in terms of four well-integrated principles. First, a participatory approach takes the poverty context as a point of departure. It focuses on people's own assessment, valuation and interpretation of life changes, and what is causal to those changes. Second, the approach is bottom-up, based on individual and group discussions among presumed beneficiaries of development interventions. Third, the approach takes a long-term perspective, spanning a few decades, as to incorporate the experiences and perceptions of different age groups within the population. Different development initiatives may be assigned different meaning and value according to people's life cycle and accumulated knowledge and experiences. Fourth, the perspective strives for holism, in a sense of keeping an open eye to all sorts of development initiatives, irrespective of sector and agency. However, given the first three principles, the boundaries of this ‘holistic’ perspective are inherently set by local people's perceptions of development initiatives in the area. Some initiatives may thus go unnoticed, if not perceived as a ‘development’ initiative by the local population. This warrants the participatory assessment to be sufficiently conceivable and detailed.

The specificities of operationalizing a participatory approach to impact assessment can vary across place and time, but should always adhere to the above four principles. The way in which we decided to operationalize and further improve the approach was in two subsequent (learning-by-doing) stages. The first stage was the case study in Pokot area, in Kenya. Further improvements on the basis of lessons learned were made in the second stage, among other things during the case study in Sandema area, in Ghana. In Pokot, Kenya, the most important research activity was the organization of three participatory impact evaluation workshops. The researchers facilitated a local-level assessment of two to three decades of change, outside interventions, and their perceived impact. Two workshops took place in 2001 (those in Chepareria and Kodich) and one in 2002 (the workshop in Kiwawa). Each workshop lasted three days. The participants consisted of between thirty and fifty local leaders; that is, elected councilors, appointed chiefs and assistant chiefs, local church leaders, women group leaders and teachers. Some civil servants also participated. They were assisted by the West Pokot Research team,12 which had carried out a thorough document analysis and which had long-standing experience in socioeconomic, geo-graphical and cultural research in the area.

The workshop programme consisted of the following activities. People were asked (and assisted) to write personal life histories, with special attention to what is locally regarded as the major disaster period (1979–81). There was a joint reconstruction of the history since 1979, focusing on the problem years, and also a joint reconstruction of all development projects in the area, by all relevant agencies, and in all sectors. This was followed by a major discussion on poverty and changes in capabilities between 1980 and 2002. The discussion on capabilities centered around six life domains: natural, physical, human, economic, cultural and sociopolitical capabilities, on the basis of an amended version of Bebbington's typology (1999). This culminated in an assessment of the impact of each of the projects and activities on each of the six groups of capabilities, and on their importance for poverty alleviation. In addition, the participants of subareas were asked to rank all projects per area and to select the ten ‘best’ and the ten ‘worst’ projects. In the workshop in the third research area this was done per subgroup of men and women. Finally, there was a concluding discussion of the development prospects of the area and this frequently turned into a debate on the virtues and vices of donor-supported development initiatives.

In the analysis of this wealth of data,13 all the development initiatives were listed according to four major types of actors/donors: (1) the government, (2) the ASAL programme, (3) churches and their development agencies, and finally (4) nonchurch NGOs. Although central and local government agencies were present in the area, they were included only if the workshop participants regarded these activities as development initiatives. Often, such activities had been funded by a foreign donor agency (e.g., SIDA, the World Bank). The ASAL programme was treated as a separate agency (even though it was formally part of the government) because of its sheer size, and people's perception of ASAL as more of an NGO than a government body. Before discussing the evaluation findings coming out of these workshops, we will first take a closer look at the areas under study and poverty and development problems observed.

11.3 HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVES IN POKOT, KENYA, 1979–2009

The (then) West Pokot District in northwest Kenya was considered a typical example of a marginal, vulnerable area during the last twenty years of the last century. Far away from the economic and political centers of gravity in Kenya, in an unruly border zone near Uganda, the Pokot people had to cope with occasional droughts, resulting in poor grazing, livestock losses, crop failure and hunger. Livestock diseases undermined livelihood security. Human disease epidemics resulted in deaths and high health costs. Raids by neighboring pastoralists, and counter-raids, resulted in the loss of both human life and livestock, the destruction of property and restrictions in movement(affecting grazing negatively). Army activities resulted in human deaths, livestock confiscation and slaughter and a general feeling of insecurity. Poverty in Pokot is perceived to be widespread, and this is expressed in terms of deteriorating livestock numbers per capita, and occasional famines due to livestock deaths, harvest failure and violence. Many Pokot also express feelings of despair as a result of being cut off from opportunities to continue their preferred way of life.

A large number of agencies promoting ‘development’ (and Christianization) have been active in the Pokot area since about 1979. A lot of projects started as disaster aid, during and after a devastating crisis period in the area between 1979 and 1981. At the time, the Kenyan Provincial Administration governed the area, but it was rather weak, government departments generally suffering from a lack of development funds and their civil servants (most of whom originated from elsewhere in the country) coping with meager salaries and rapidly decreasing purchasing power, which negatively affected their performance. Soon, a lot of multilateral and nongovernmental agencies operated in the area. These included the Red Cross, the World Food Programme, UNICEF, the Netherlands Development Organization SNV, two Dutch-sponsored so-called Harambee Foundations (one focusing on health and one on water), Christian Children's Fund, World Vision and more than ten churches of various dominations, supported by a large variety of foreign well-wishers. The biggest development programme in the area was the ASAL Programme (the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Programme) for the District of West Pokot as a whole. Although almost all the funds came from the Netherlands, it was presented as ‘development collaboration between the governments of Kenya and the Netherlands’. Initially most of its activities were related to agriculture, livestock/veterinary health, forestry and environment, education, water, social services and public works/roads. It operated mostly through the District Development Committee (DDC), an amalgamation of civil servants (most of them not from the district) and church/NGO representatives, although it was not linked to the Local Council. Hence, most of the people involved in the DDC were nonelected non-Pokot (whereas the majority of the Local Council consisted of elected Pokot councilors who nevertheless had very limited powers). As a consequence, ‘government’ was regarded as a ‘foreign body’, and some Pokot even regarded the civil service as part of ‘the enemy’. Pokot often balance mistrust (“they just want to exploit or humiliate us” and “ they are just there to fill their pockets”) with high expectations (”after all those years of neglect we deserve progress” and” the government should at last give us a, b, c”).

The year 1979 was taken as an obvious starting point by the participants in the study workshops: it was the beginning of a period of disasters, which seriously undermined the economic independence of the mainly pastoral Pokot in the research area. Before 1979 the area was a remote backwater of Kenya, for a long time even a ‘closed district’, and partly administered by Uganda, which utterly neglected it; 1979 was also widely regarded as a turning point because suddenly a lot of outside agencies came to the area, mostly to provide disaster mitigation support.

11.4 PARTICIPATORY IMPACT ASSESSMENT IN POKOT, KENYA

During the workshops a detailed chronology of events between 1979 and2002 was drawn up. The events recorded included cattle raids, epidemic human and cattle diseases, the activities of various government, church and NGO agencies, military action, political events, famine, food relief, droughts and floods, death of a leader, etc. Next, the perceptions of positive and negative changes in the living conditions in the area during the last twenty years were recorded.

Pokot, Kenya: Local Perceptions of Changing Capabilities

The answers were arranged according to the six capability domains. Positive as well as negative perceptions were noted for each of these domains. For instance, the example of the findings in two of the six capability domains in the Kiwawa workshop (Dietz and Zaanen 2009; all quotes are from this publication) shows the tensions of change as perceived by the Pokot respondents in this area. In the economic/financial domain the perceived positive changes were formulated as being:

More businesses. Some income through the sale of miraa and the mining of gold and ruby. Interaction with other communities outside the area. More organisations and donors have come to assist the people. Money is now accepted. People feel superior when they have it. It improves one's living standard, and it can raise one's status. More (exchanges of) commodities improved the development of the area.

While the negative assessment was

Low employment and lack of job opportunities. Poor production of both livestock and crops. Inflation of prices of commodities. No credit facilities for businessmen and women available. Money can easily be stolen. Money creates poverty and envy. Civil servants who are employed far from home can easily divorce. Spread of diseases and use of drugs by youth. Loans may lead to stress.

Table 11.1 Categories of Project Assessment in the Pokot Area

| Category of assessment | % of all projects |

| (1) project never really started, or project was negligible | 13 |

| (2) project existed, but had no lasting impact, ‘nothing to be seen on the ground’ | 10 |

| (3) project is still ongoing, no impact to be assessed yet | 33 |

| (4) project was finished and had an impact perceived as positive | 40 |

| (5) project was finished and had an impact perceived as negative | 4 |

Source: Dietz and Zaanen (2009:152).

In the social and political domain people had a positive assessment of the following aspects:

This community counts on the multi-party system for positive changes. More Pokot became national leaders. More local people are now in local leadership positions. More organisations are active in the area (women groups, youth groups).

But the downside of this was thought to be:

Little has been done by the elected leaders and the government. The community feels neglected by their elected leaders because of their greed and corruption. The government has also been corrupt. The elected leaders live far away from the people. Nepotism and tribalism are prevalent.

The picture above reveals a strong ambiguity in perceptions. On the one hand the participants speak the language of development, in which some changes are perceived to be the fruits of ‘modernity’, like a monetary economy, more democracy and more civil society freedom. However, the perceived positive change remains wishful thinking to some extent, where as the economic and social consequences of modernity are perceived to be quite negative as well: money, but little wage-labor opportunities, rising prices, stress and lack of credit facilities; democracy, but greed, corruption, nepotism and tribalism…

Table 11.2 Assessment per Type of Donor, Pokot Area, Kenya

Pokot, Kenya: Attributed Impact

During the workshop, people discussed the roles of the various external agencies, which were contributing to change. It became clear that a lot of participants had a grudge against ‘the Government’. This was mainly due to military operations when the Pokot were disarmed by force (1984–86). The government was also negatively associated with the way a hydro electricity project was being realized without compensation for those who had lost land. People were much more positive about non governmental and church agencies involved in development projects.

Table 11.3 Impact on Capability Domains in the Pokot Area: Most Pronounced Differences between Donor Agencies

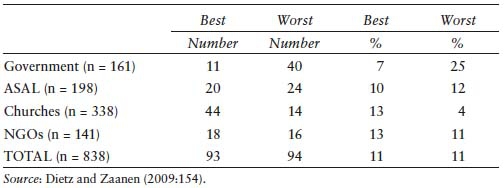

Table 11.4 ‘Best’ and ‘Worst’ Projects for Four Types of Donors in the Pokot Area

The various judgments by the workshop participants concern a total of 838 different projects in ten geographical research areas during the last twenty years. These have been identified by the participants and arranged per type of donor. Church organizations have been responsible for most projects (338), followed by the ASAL programme (198), the government(161) and nonchurch NGOs (141). Table 11.1 gives the people's summarized assessment of all these different projects.

Where measured separately, men and women often expressed a different opinion. Other differences in opinion were expressed in the ten areas represented during the workshops. The outcomes can be summarized as follows.

Projects by the government had a higher score than average on ‘negligible’ projects (”just words; nothing really happened”), a lower than average score on ‘positive impact’, and a remarkably high score on ‘negative impact’. Projects, which were part of the ASAL programme, had a relatively high score on ‘positive impact’, but also a relatively high score on ‘unsustainable impact’. Projects, which had been implemented by the many churches present in the area, had a relatively high score on positive impact, but also a slightly higher score than average on ‘negligible’ projects. Nonchurch NGOs had a remarkably high score on ‘negligible projects’, but are markably low score with regard to ‘negative impact’. These results are shown in Table 11.2.

The impact of all projects combined was considered highest in the domain of human capability (people's skills, knowledge level, health). The perceived impact was less on changes in the natural capability (pastures, agriculture, water supply) and on cultural capabilities (religion, tradition, moral questions). All four kinds of donors were active in all domains, and they had a perceived impact on all capabilities, although there were a number of interesting differences, also between the more remote and the more central areas. A summary of these results can be found in Table 11.3.

Workshop members were asked to choose ten projects which they regarded as the best for their area (with the greatest positive impact) and ten projects which they regarded as the worst for their area (with the greatest negative impact, or the largest difference between expectations and outcome). In total, the workshop participants for ten areas selected ninetythree ‘best’ projects and ninety-four ‘worst’ projects. The ‘best’ and ‘worst' scores are presented in Table 11.4.

A broad picture emerges of the way the population favored development initiatives from outside. This picture also sheds light on the factors influencing commitment, ownership and empowerment by those for whom the initiatives are meant, concepts which have figured so prominently in the ideologies of development cooperation. In the Pokot area, in general churches are considered to be the best development agency and the government the worst. ‘Impact’, in the perception of the participants, not only means reaching the targeted results of a project or programme, but also the way the activities have been initiated and implemented (the process).

Bottom-up managed projects, with a long-term commitment, were valued most positively. The same applies for projects treating the population ‘with respect’. Building and maintaining mutual trust and long-term commitment were considered the most valuable quality of aid-providing agencies. In the area under consideration, peace building and providing basic security against violence, including the violence of government agencies, also became important issues. With long-term commitment and trust so central to positive judgments, one wonders about the wisdom of (some) donors to have limited field presences and then only for restricted periods (with or without an exit strategy). Donors that were on the point of leaving generally were regarded as bad, and this clarifies a great deal about the not so positive ex-post attitude towards the ASAL programme, which had just ended. One of the lessons learned is that, in the initial phases of development programmes, considerable energy should be spent on understanding people's behavior and its cultural roots rather than on concentrating on the functioning of the government machinery. Consequently, one of the major challenges in development cooperation and in development research is to reconcile the development focus with a cultural focus—see also Pouw and Gilmore in Chapter 2 of this volume.

11.5 PARTICIPATORY ASSESSMENT OF DEVELOPMENT IN SANDEMA, UPPER EAST GHANA

In the project in Ghana (and Burkina Faso) we further built upon the lessons learned in the Kenya case study. In Ghana we selected various areas for workshops in the north. Northern Ghana is generally regarded as Ghana's backwater, with far higher levels of poverty compared to the south. Some parts have a high population density, and experience rather massive (seasonal and permanent) out-migration. One of those areas is Sandema, in the western part of Upper East Region, not far from the border of Burkina Faso.14 As in Kenya, a ‘PADEV workshop’ takes place over three days at a location where meals and if needed accommodation are provided so that the participants do not have to return home in the evening. During the first day the participants presented and discussed their own development stories, in separate groups of relatively old and relatively young women, and of relatively old and relatively young men. Local officials took part in these discussions, but in a separate group.

Sandema, Ghana: Local Perceptions of Changing Capabilities

For each of the six capabilities domains, the participants in Sandema compared their current situation with that of their fathers or mothers when they were the same age. Thus the groups articulated the changes that have taken place over the past twenty-five to thirty years. They assessed the changes as ‘positive’ or ‘negative’, and then qualified these assessments by adding negative aspects of the changes they considered to be positive, and vice versa. Once they had concluded these assessments, the groups listed the most important events that have occurred over the last three decades.

The groups continued to discuss their perceptions of wealth and the attributes in the research area that determine whether someone is considered to be very rich, rich, average, poor or very poor. In addition, the participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire with questions about themselves, their parents, siblings and children. Their responses can be used as additional material that can be compared with those of their next of kin. The participants completed these questionnaires over the three days of the workshop. Those who couldn't do it alone were helped by those who could, and one facilitator checked all forms and did the analysis.

Sandema, Ghana: Attributed Impact

On the second day, the participants worked in separate groups. The local officials formed one group so that they could express their views without influencing the villagers. The other participants were split up into subgroups per area. The day began with stocktaking of all development initiatives that have been launched in the research area over the past thirty years. The participants listed the name of the initiative, the sector in which it took place, the initiating agency or agencies, the financial donor(s), the period during which the initiative was active and other relevant details. In practice, it was established that the initiating agencies can be divided into five main groups: government agencies, faith-based NGOs (including the development branches of churches and mosques), non-faith-based NGOs, private-sector agencies (such as private banks or telecom companies) and local private initiators.

After this stocktaking, the groups were split into male and female subgroups that then assigned values to each initiative in their respective areas. First they ranked the projects on the basis of their usefulness and actual impact they have had on people's lives. Subsequently, each initiative was assigned to one of the following five categories:

# relatively new and still too early to say anything certain about their impact;

-- — very much disliked and should never have been launched;

- looked good on paper but produced very few outputs, or had an egligible impact;

+ some visible or tangible outputs, but not sustainable;

++ lasting positive impact ('successful initiatives, also in the medium and long term’).

Figure 11.1 Participatory assessment of impact of initiatives of different types of development agencies on five wealth classes in Sandema, Ghana.

Source: Dietz et al. (2009:31).

The groups could further differentiate the initiatives with a lasting positive impact into those that reached many people, and those that affected the lives of only a few.

On the third day, the subgroups formed at the start of the second day selected the five ‘best’ and five ‘worst’ initiatives from the long list they compiled the previous day. For each of the five best initiatives they decided which wealth class benefited the most and which the least. They did this for each of the projects by distributing ten stones among the five wealth classes distinguished on day one15.

The assessment of perceived changes in Sandema revealed a rich diversity of opinions and attitudes. This reflected a multitude of subjective views of the changes that have occurred as mixtures of ‘good’ and ‘bad’. However, underlying this diverse spectrum of opinions some clear general features could be identified. Differences in opinion are apparent between men and women, between old and young and across village communities. Assigning values to the impacts of change involves a process of negotiation among many people who occupy different positions in society. For individuals as well as for groups, this often results in ‘yes, but…’ responses in the case of changes that are valued as mostly positive, and ‘no, although…’ responses in the (few) case of changes that are judged as mostly negative. There is a strong cultural component in assigning values, and a historical path-dependency related to personal life-cycle in judgments. People tend to judge certain changes in the context of their own views and experiences, or those of their ancestors. It is not always clear what is fact, fiction or myth. By including people of different age groups, gender and social status, we build in a tool to compare and contrast certain viewpoints and valuations in a critical reflexive manner

In Sandema, the workshop participants assessed the success or failure of a total of 341 development initiatives. Figure 11.1 illustrates the combined results of the values attached to the ‘best’ initiatives (55 of them)and their impacts on the five wealth classes. It shows how a basically qualitative approach can yield rather informative quantitative results.16The results probably come close to intuitive assessments of those who are familiar with the area, but the differences between the ‘types of development agency’ are subtle in degree, and should discourage us from making simplistic judgments. It seems that many Ghanaians, whether literate or not, are experts in the subtleties of complexity thinking (Fowler 2008).

11.6 SUMMARY OF PARTICIPATORY ASSESSMENT FINDINGS

In the Pokot area, in Kenya, an avalanche of church-based and nonchurch-based NGOs became responsible for a lot of development initiatives, quite separate from government and Dutch-sponsored ASAL programme initiatives. The local people judged these agencies in more positive terms, and this was particularly the case for churches with along-term presence in the area.

In the Sandema area a more restricted number of NGOs has been active, and their activities have generally been evaluated positively as well. Where initiatives were valued more critically, these were often the ones where rather daring agricultural initiatives had disappointing results. But in those cases the agencies were not evaluated negatively, as their experimental attitude—alongside trustworthy support to basic rural services— was seen as an asset, not as a problem. In northern Ghana many government initiatives have also been valued quite positively, for the same reasons, and the general attitude to ‘government’ is far more positive than in the Kenyan Pokot area.

- It appears that the appreciation of initiatives by local stakeholdersis often not in the first place based on these initiatives reaching their purpose (effectiveness) or on their cost effect relationship (efficiency) but on the way the initiative (‘the project’) was started and executed(its process). This emphasis on the style of initiative also includes the measure of respect paid to the target groups, the measure of flexibility in dealing with changing circumstances, the long-term commitment of the intervention agencies, and the susceptibility for local inputs in the decision-making process. In spite of a rather good stakeholder appreciation of the big Dutch-funded programmes in the Pokot area, in case the latter adopted the desired style, and in spite of the recognition of their efforts, these programmes have not been able to achieve their goal of alleviating poverty. No appreciable changes have occurred in the economic lives of the majority of the population, although other capitals and capabilities have often improved considerably— for instance, the improvement of education and the provision of drinking water. The income-oriented and employment-oriented initiatives have either been too limited in scope, or too short, or too superficial to have any lasting impact. Often, they have remained restricted to fighting symptoms and have not really focused on the processes which really cause poverty. And during the 1990s, government (and ASAL) attempts to improve production, marketing and income generation were gradually pushed aside, as no longer fitting the ideology of the time. Investments in services (water, health, education, women group formation) did have major impacts on mainly human and social-political capabilities of the population (the social side of poverty), but in such one-sided ways that major problems can be expected in the future. In remote areas like Pokot, the policy theory behind withdrawing from the productive sector, and leaving that to the private sector, is flawed. There is hardly any private sector to count on.

What is important is that people's opinions and behaviors are based on these mixtures of what they regard as relevant truths, even if these are obviously wrong or distorted. Evaluations often conclude that x percent of development projects have failed, or y percent have been successful, judgments that often are picked up and magnified by the media, public-opinion makers and political entrepreneurs. However, the truth cannot be captured in one-dimensional conclusions. Villagers and local officials in areas such as northwest Kenya or northern Ghana will brand them as mere catchphrases that represent a distortion of the truth as they see it.

In northern Ghana, the persistent attitude among the major rural development agency in the Sandema area (PAS, the ICCO-supported NGO for agricultural and rural development) to continue supporting farmers with their agricultural experimentation, and supporting farmers to find and reach markets, is part of the explanation why this area does not have such a one-sided development profile. Development investments in services as well as in the productive sphere have taken place, leading to better agricultural prospects (expanded agricultural land use, new crops and varieties, better marketing/higher cash income, higher productivity) and a steady out migration of locally educated youth, feeding a steady stream of remittances from ‘down South’. Many migrants from Sandema go to central Ghana to start farms there, or work as laborers on farms, and they move to the big cities like Accra. These remittances are then partly being used to finance further agricultural and marketing experiments, and to support a growing local (cooperative) banking system to back up agricultural enterprise investment and growth.

However, the appreciated bottom-up principles in the programme approaches were often overruled by policy decisions at higher levels. In Pokot and in Sandema, development programmes had to put more emphasis on the environment and on services and less on productive activities as a result of changing donor (and government) mores. Changing orientations (each with their proper sectors, priorities, criteria and conditions) were often imposed on the programmes in a top-down way, and one after the other. The major donor assumption in the 1990s was that in a liberalized economy the private sector would automatically take over the role of the government on the market. In remote districts in Africa this (killer) assumption has appeared to be wishful thinking. For the reasons mentioned above, in the Pokot area the programmes have appeared significantly irrelevant when it comes to responding to poverty problems in the areas concerned, and its one-sided attention for services. A lack of attention for employment and income generation creates a ticking time bomb in the form of young people who are disillusioned, undereducated and poor. Moreover, by continually making new demands on economy and governance, the safety valves inherent in the old systems (preferential prices, social securities, checks and balances in the local village administration) were negatively affected, and these are presently replaced by foreign regulations (‘codes of conduct, ‘contracts’, ‘tender procedures’) in the name of good governance. These regulations have been instituted to enforce integrity. However, neither integrity nor transparency can be guaranteed with these new regulations, and both the local population and donors became increasingly irritated by corruption. In the Sandema area a strong NGO sector has resisted some of the donor ideologies of the recent decade, and has continued to support farmers in their productive and income-generating activities. A strong orientation on Christian values has limited the extent to which initiatives were sidetracked or donor money stolen. Of course a different overall context mattered as well, with Kenya going through a major identity and economic crisis, and Ghana being in a more positive mood.

Toppling the evaluation perspective, and making both the poverty question and the stakeholder impact assessment of all initiatives the points of departure (the stakeholders’ reality, language and logic) revealed fundamental problems in the setup and in the approach to poverty alleviation in marginal rural areas in Africa. The basic problems in poverty alleviation seem to concern the role of the government, its strategy and procedures— and also the role of donors, or the effect of donor-steered aid. It so happens that, given the introduction of more centralized forms of development cooperation (sector wide approach, budget support, basket funding, etc.), the assumption is that the government that benefits from this kind of aid is capable of dispensing this aid from central to decentralized levels according to broad sector policies or even broader poverty-reduction strategies. Another assumption is that the population has been heard and agrees with these programmes (cf. ‘The Voices of the Poor’; inputs in PRSPs), acknowledges their importance and will therefore ‘participate’ in them. There is a lot of wishful thinking behind these assumptions.17

People's ideas about vulnerability, security and even survival are not only related to basic commodities like food, shelter and protection from violence, but also to issues of identity. The perception of poverty is thus rooted in culture as well. In a society in which pastoralism is perceived as the preferred way of life (even if only a small minority of the people can still afford to live that way, as in the Pokot area in Kenya), any project initiative that supports the rebuilding of herds and flocks, and that improves animal health, access to water and (improved) pasture, tends to be seen as ‘good’. However, if donors do not live up to promises in these areas, people are quick to judge these initiatives as ‘useless’, ‘negligible’ or ‘unsustainable’. However, people have also realized that they need additional support mechanisms for survival as a community, and many initiatives to improve their health, education and skills levels have been highly appreciated. People realize, though, that education without the prospects of (local) employment is a major threat to social cohesion. A large group of educated poor people is already present in the district and they form a basis for a lot of social (and political and cultural) instability. It is a ticking time bomb, which is neglected by most of the development agents.

11.7 CONCLUSION

In the social sciences and humanities, the positivist assumption of objectivity in the process of knowledge creation is gradually being abandoned. Researchersno longer claim to have the monopoly on what is ‘true’ and what is ‘false’. The attention that is given to indigenous knowledge is growing, and a range of new methodologies that borrow elements from a variety of evaluation approaches is now being developed to formulate hypotheses and test assumptions. Philosopher Karl Popper's theory of ‘three worlds of knowledge’ is gradually being replaced by more complex combinations of knowledge systems. What is true for systems thinking in general is certainly true for knowledge systems (see Williams 2008). Making sense of current and recent history is a subjective, value-driven activity, both for laypeople and for scientists. Back in 1928, the sociologist William Thomas formulated a theorem which states that ‘if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences’ (see Merton 1995). His proposition has become popular among critical realist and postmodern movements within the social sciences and humanities. Judging what is true or false, good or bad, useful or useless, beautiful or ugly, is a cultural process, bound by but full of specific pathways through time and space. Development is a broad and highly contested concept, and ‘evaluating development’ has become an exercise in judging norms and values. It is therefore useful to examine how subjectivity entered the debate on evaluating development, and how it has gained in popularity among researchers. In Evaluation Evolution, Otto Hospes (Hospes 2008) attempted to classify three evaluation approaches to development, one of which was ‘complexity evaluation’ (see also Fowler 2008). In our approach we go one step further, and look at the promise of involving recipients in the assessment of the effects and impacts of the development assistance they have received. Local people's perceptions, grounded in real-life experiences, are taken as the differentiated representations of reality.

One of the basic problems in participatory assessment exercises as we have done is the composition of the teams, which are supposed to assess development and development initiatives. It is important to include local leaders and people who are locally being regarded as the best informed ones. However, this introduces a major risk of reproducing the local power structures and of silencing locally marginal, or different, voices. Both in the Pokot and in the Sandema areas we have tried to solve this problem by making the workshop big enough (50 people) to include others than the most obvious ones, and by organizing separate sessions for the local leaders and the common villagers. For the same reason, we have organized separate sessions (and stimulated independent valuations) for old and young women and for old and young men. In the recruitment of participants we have explicitly asked for diversity, in terms of gender, age, religion, ethnic identity, level of education and ancient versus immigrant inhabitants. In Ghana we have even repeated the exercise among schoolchildren (with surprisingly rich results; see Kazimierczuk 2009).

A second problem is part of the renowned critique to participatory evaluation in general, namely the subjectivity of the approach that is bound to generate positive assessments of those initiatives that are, one way or the other, associated with the evaluators. Thus far, the chronology of the workshops was such that we always started with the history of development initiatives and worked our way through via perceived changes in capabilities to the attributed impacts made by actor/donor. In order to build in more checks and balances for critical reflection, we organize the chronology of inquiry in such a way that the assessment of the most important changes in capabilities comes prior to the question what have been major drivers of these changes. This question will be asked before attributing impact.

Although the answers thus generated will still be subjective in nature at one level of analysis, they allow the researcher/evaluator to move to a more objectivated analysis of comparing and contrasting subjective experiences and perceptions at another level.

A third and final problem that we have come across so far is almost impossible to solve. The people who are locally regarded as the (ultra)poor often exclude themselves from participatory exercises like these. They either shy away from social gatherings or simply are too busy surviving, with very limited capacity and time to spend on networking and social activities. Being utterly isolated (if not despised) in their local social context is often part of the reason why they are so poor and why they remain so poor. This problem could not be resolved within the workshops organized; it requires a different approach and field-research methods. In the remaining part of our research activities for the current project in Ghana and Burkina Faso, we will try to solve this problem of (self)exclusion of the (ultra)poor by first doing a complete poverty assessment and then organize specific research activities among these groups, which are at the same time income-generating activities. These activities should not, however, attract people who are better-off.

A final remark should be made in regard to the evaluation agendas of NGOs and other development stakeholders. It is interesting to see that, at present, development NGOs are trying to develop alternatives to top-down donor-driven approaches to evaluation. Although this is happening on the sideline of enforced monitoring and evaluation protocols, which—in the Netherlands—now go together with the new government-assisted co-financing programmes of Dutch NGOs working in Africa, Asia and the Americas, it is also interesting to see that there is more room for experimentation and more south-north and university-NGO collaboration with a view to taking participatory evaluation seriously. At a higher level of scale, experiences gained by Oxfam-NOVIB are also insightful (e.g., see Wilson-Grau and Nunez 2007). At an international level, Robert Chambers still inspires many colleagues to apply creative solutions to a continuing challenge in development studies (e.g., Brisolara 1998, and other contributions to the journal New Directions for Evaluation) and in studies of societal change in general, including in ‘developed’ contexts (e.g., Hayward et al. 2000).

NOTES

1. For an overview of a recent debate in the Netherlands about the ins and outs of Measuring Results for Development, please visit www.dprn.nl. In a ‘Letter to Parliament’, the Netherlands minister for development cooperation, Bert Koenders, wrote that ‘Development cooperation is among the most researched and evaluated policy domains in the Netherlands’; 11 May 2009).

2. Classic texts, which were the basis of a lot of ‘evaluating development’ exercises with a rather technocratic and expert-driven approach, include Casley and Kumar (1992).

3. See, for example, Hulme (2000). For interesting examples in many fields, see www.iaia.org of the International Association for Impact Assessment (based in North Dakota, US). They define ‘impact assessment’ basically as an exante activity (”Impact assessment, simply defined, is the process of identifying the future consequences of a current or proposed action”), but there are many ex-post lessons as well. We use the word ‘assessment’ in an ex-post way: people assess the past development trajectory, and the initiatives of theagencies involved. An interesting example of a combination of ex-ante and ex-post impact approaches, based on the experiences of GTZ, is given by Douthwaite et al. (2003).

4. These ideas have been developed in a joint article, together with Sjoerd Zaanen, in which he reflected on his experiences in Mbulu, Tanzania, and I on my experiences in Pokot, Kenya; see Dietz and Zaanen 2009.

5. Robert Chambers has written many influential publications in this field (e.g., 1983, 1994, 1995, 1997). Together with others he was involved in the famous World Bank-funded exercise ‘Voices of the Poor’ (see Narayan et. al. 2000). There is a host of related methods, with names like ‘sondeo’, ‘rapid rural appraisal’, ‘participatory appraisal’, ‘inclusive assessment’, and so on. One of the first texts was Hildebrand (1981). This has inspired us to do ‘sondeos’, when we started our research programme to support the Arid and Arid Lands Development Programme in Kenya in 1982 (see Dietz and Van Haastrecht 1983). Perhaps the most useful summary of these approaches is Schönhuth and Kievelitz (1994). Recently, Chambers has further shifted the approach to what he calls PLA: Participatory Learning and Action (e.g., 2002 and 2007).

6. See Scriven (1980), Greene (1988), Guba and Lincoln (1989), Garaway (1995), Keough (1998), Jackson and Kassam (1998), Themessl-Huber and Grutsch (2003), Holte-McKenzie, Forde and Theobald (2006), Forss, Kruse, Taut and Tenden (2006). In his recent MSc thesis in international development studies at the University of Amsterdam, Jerim Obure gives a summary; see Obure (2008). An interesting recent Dutch PhD study about participatory monitoring experiences is Guijt (2008).

7. A good overview can be found in Estrella (2000). Also see Roche (1999).

8. A classical text is Oakley (1991). Recent critiques include Cleaver (1999), Kapoor (2002), Platteau and Abraham (2002), Cornwall (2003) and Williams (2004). A special branch is PTD, participatory technology development. For an evaluative overview, see Joss (2002). A recent textbook with a lot of useful insights about doing ‘participatory research’ is Laws et al. (2003).

9. We prefer the word ‘initiatives’ as the word ‘project’ or ‘development programme’ sometimes excludes local-level innovations.

10. They formed part of one of the key components of Dutch development assistance to Africa during that period, the integrated rural development programs (see Sterkenburg and Van der Wiel 1999), which stopped rather suddenly after 2000 (see IOB 2008, Chapter 9, about rural development, pp. 257–292—in Dutch).

11. The research programme on ‘Participatory Assessment of Development’ started in 2008 and will last until 2012. Research sponsorship comes from ICCO, Woord and Daad and Prisma (three Dutch NGOs with a Christian identity), and it is a collaborative activity by the University of Amsterdam / AISSR, the University for Development Studies in Tamale, Ghana, and EDS (Expertise pour le Développement du Sahel) in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. The results of the study an be found on www.padev.nl; preliminary lessons learned can be found in Chapter 2 of Dietz (2011).

12. Led by Rachel Andiema and Albino Kotomei, and also consisting of Simon Lopeyok Lokomorian, Jacinta Chebet, Helen Nasamba, Moses Kamomai and Galdino Losya.

13. Basic data in Andiema et al. 2002. For Kiwawa, a first analysis (with many more details) has been presented in Andiema et al. 2003.

14. The organization of the Sandema workshop was in the capable hands of Dr. Francis Obeng of Tamale University for Development Studies. Other facilitators were Professor David Millar, Professor Saa Dittoh and Dr. Richard Yeboah, Kees van der Geest, Dr. Fred Zaal, Wouter Rijneveld, Dieneke de Groot, Martha Lahai, Agnieszka Kazimierczuk, Mamudu (Mamoud) Akudugu, Frederick Bebelleh, Margaret Akuribah, Adama Belemviré, Ziba, and Emmanuel Akiskame.

15. In September 2008 there were three workshops, of which the Sandema workshop was one; in 2009 an additional three workshops have been organized; and in 2010 three more. In these workshops, the participants also tried to attach values to the distribution of benefits immediately after a project had ended. By repeating the exercise in the future, it should be possible to compare any shift in opinion about a successful initiative over time.

16. For a recent discussion about quantitative and/versus qualitative methods of impact evaluation (by Sabine Garbarino and Jeremy Holland, March 2009, for DFID and the GSDRC) see: www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/EIRS4.pdf .

17. Again, these ideas come from the paper jointly written with Sjoerd Zaanen (Dietz and Zaanen 2009).

REFERENCES

Andiema, Rachel, Ton Dietz, and Albino Kotomei. 2002. “Workshop Proceedings of the Participatory Impact Evaluation of Development Interventions on People's Capabilities in (I) Chepareria Division, (II) Kacheliba and Kongelai Divisions, and (III) Alale and Kasei Divisions, West Pokot District, Kenya.” Amsterdam/Kapenguria: West Pokot Research Team.

Andiema, Rachel, Ton Dietz, and Albino Kotomei. 2003. “Participatory Evaluation of Development Interventions for Poverty Alleviation among (Former) Pastoralists in West Pokot Kenya.” In Faces of Poverty. Capabilities, Mobilization and Institutional Transformation. Proceedings of the International CERES summer school 2003, edited by Isa Baud, 193–209. Amsterdam: CERES.

Bebbington, Anthony. 1999. “Capitals and Capabilities: A Framework for Analyzing Peasant Viability, Rural Livelihoods and Poverty.” World Development 27 (12): 2021–2024.

Bieckmann, Frans. 2008. “Editorial: First Aid, Second Opinion.” The Broker 6: 3. Accessed March 14, 2011. http://www.thebrokeronline.eu/en/Special-Reports/Special-report-Deep-democracy.

Bieckmann, Frans. 2008. “Special Report: Deep Democracy.” The Broker 10: 9–16. Accessed March 14, 2011. http://www.thebrokeronline.eu/en/SpecialReports/Special-report-Deep-democracy.

Brisolara, Sharon. 1998. “The History of Participatory Evaluation and Current Debates in the Field.” New Directions for Evaluation 1998 (80): 25–41.

Casley, Denis, and Krishna Kumar. 1992. “The Collection, Analysis, and Use of Monitoring and Evaluation Data.” Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Chambers, Robert. 1983. Rural Development: Putting the Last First. London: Longman.

Chambers, Robert. 1994. “The Origins and Practices of Participatory Rural Appraisal.” World Development 22 (7): 953–969.

Chambers, Robert. 1995. “Poverty and Livelihoods: Whose Reality Counts?” Environment and Urbanization 7 (1): 173–204.

Chambers, Robert. 1997. Whose Reality Counts: Putting the Last First. London: IT.

Chambers, Robert. 2002. Participatory Workshops: A Sourcebook of 21 Sets of Ideas and Activities. London: Earthscan.

Chambers, Robert. 2007. “From PRA to PLA and Pluralism: Practice and Theory.” In The Sage Handbook of Action Research: Participatory Inquiry, edited by Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury, 297–318. London: Sage.

Chambers, Robert, Dean Karlan, Martin Ravallion and Patricia Rogers. 2009.. ”Designing Impact Evaluations: Different Perspectives.” Working Paper 4, International Institute for Impact Evaluations.

Cleaver, Frances. 1999. “Paradoxes of Participation: Questioning Participatory Approaches to Development.” Journal of International Development 11 (4): 597–612.

Cornwall, Andrea. 2003. “Whose Voices? Whose Choices? Reflections on Gender and Participatory Development.” World Development 31: 1325–1342.

Dietz, Ton. 2011. “Silver Lining Africa. From Images of Doom and Gloom to Glimmers of Hope. From Places to Avoid to Places to Enjoy.” Inaugural Address. Leiden: Leiden University.

Dietz, Ton, and Annemieke van Haastrecht. 1983. “Rapid Rural Appraisal in Kenya's Wild West: Economic Change and Market Integration in Alale Location, West Pokot District.” Working Paper 396, Nairobi: Institute for Development Studies.

Dietz, Ton, with Koen Kusters, Alpha Barry, Sylvia Borren, Paul Hoebink, Tineke Lambooy and Herman Mulder. 2008. “Statement on Policy Coherence for Development: Aid, Trade, Investment, and Other Issues.” Annex to Inspiring a Global Mindset—an Overview of 2007. Amsterdam: Worldconnectors/NCDO (see www.worldconnectors.nl).

Dietz, Ton, and Wiegert de Leeuw. 1999. “The Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Programme in Kenya.” In Experiences with Netherlands Aid in Africa, edited by Jan Sterkenburg and Arie van der Wiel, 37–57. The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Dietz, Ton, David Millar and Francis Obeng. 2002. “By the Grace of God, the Day Will Come When Poverty Will Receive the Final Blow. The Impact of NGOs Supported by Dutch Co-Financing Agencies on Poverty Reduction and Regional Development in the Sahel. Northern Ghana Report.” Working document to the Steering Committee for the Evaluation of the Co-financing Programme, Amsterdam/Bolgatanga: University of Amsterdam/University for Development Studies Tamale.

Dietz, Ton and Sjoerd Zaanen. 2009. “Assessing Interventions and Change among Presumed Beneficiaries of ‘Development’: A Toppled Perspective on Impact Evaluation.” In The Netherlands Yearbook on International Collaboration, edited by Paul Hoebink, 145–164. Assen, Netherlands: Van Gorcum.

Douthwaite, Boru, Thomas Kuby, Elske van de Fliert and Stefan Schulz. 2003. ”Impact Pathway Evaluation: An Approach for Achieving and Attributing Impact in Complex Systems.” Agricultural Systems 78 (2): 243–265.

Estrella, Marisol, ed. 2000. Learning from Change: Issues and Experiences in Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation. London: ITDG Publishing.

Forss, Kim, Stein-Erik Kruse, Sandy Taut and Edle Tenden. 2006. “Chasing a Ghost? An essay on participatory evaluation and capacity development.” Evaluation 12: 128–144.

Fowler, Alan. 2008. “Connecting the Dots.” The Broker 7: 10–15.

Garaway, Gila. 1995. “Participatory Evaluation.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 21 (1): 85–102.

Greene, Jennifer. 1988. “Stakeholder Participation and Utilization in Program Evaluation.” Evaluation Review 12 (2): 91–116.

Guba, Eggon, and Yvonna Lincoln. 1989. Fourth Generation Evaluation. London: Sage.

Guijt, Irene. 2008. “Seeking Surprise. Rethinking Monitoring for Collective Learning in Rural Resource Management.” PhD dissertation, Wageningen University, Netherlands.

Hayward, Chris, Lyn Simpson and Leanne Wood. 2000. “Still Left Out in the Cold: Problematising Participatory Research and Development.” Sociologica Ruralis 44 (1): 95–108.

Hildebrand, Peter. 1981. “Combining Disciplines in Rapid Appraisal: The Sondeo Approach.” Agricultural Administration 9 (6): 423–432.

Holte-McKenzie, Merydt, Sarah Forde and Sally Theobald. 2006. “Development of a Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation Strategy.” Evaluation and Program Planning 29 (4): 365–376.

Hospes, Otto. 2008. “Evaluation Evolution?” The Broker 8: 24–26.

Hulme, David. 2000. “Impact Assessment for Microfinance: Theory, Experience and Better Practice.” World Development 28 (1): 79–98.

IFAD. 2007. Rural Poverty Portal. Accessed on 10 March, 2011 (citation of 2007), http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/web/guest/home .

IOB. 2008. “Het Nederlandse Afrika beleid 1998–2006. Evaluatie van de bilaterale samenwerking.” IOB Report 308, The Hague: Inspection development cooperation and policy evaluation.

Jackson, Edward, and Yusuf Kassam. 1998. Knowledge Shared: Participatory Evaluation in Development Cooperation. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press.

Joss, Simon. 2002. “Towards the Public Sphere: Reflections on the Development of Participatory Technology Assessment.” Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 22 (3): 220–231.

Kabeer, Naila. 2001. “Conflicts over Credit: Re-evaluating the Empowerment Potential of Loans to Women in Rural Bangladesh.” World Development 29: 63–84.

Kapoor, Ilan. 2002. “The Devil's in the Theory: A Critical Assessment of Robert Chambers’ Work in Participatory Development.” Third World Quarterly 23 (1): 101–117.

Kazimierczuk, Agnieszka. 2009. “Participatory Poverty Assessment and Participatory Evaluation of the Impact of Development Projects on Wealth Categories in Northern Ghana.” Master thesis (unpublished), Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, International Development Studies Programme.

Keough, Noel. 1998. “Participatory Development Principles and Practice: Reflections of a Western Development Worker.” Community Development Journal 33 (3): 187–196.

Laws, Sophie, with Caroline Harper and Rachel Marcus. 2003. Research for Development. A Practical Guide. London: Sage.

Leach, Melissa, Robin Mearns and Jan Scoones. 1999. “Environmental Entitlements: Dynamics and Institutions in Community-based Natural Resource Management.” Wolrd Development 27: 225–247.

Merton, Robert. 1995. “The Thomas Theorem and the Matthew Effect.” Social Forces 72 (2): 379–424.

Narayan, Deepa, Robert Chambers, M. H. Shah and Patty Petesh. 2000. Voices of the Poor: Crying Out for Change. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Obure, Jerim. 2008. “Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation: A Meta-Analysis of Anti-Poverty Interventions in Northern Ghana.” Master thesis (unpublished), University of Amsterdam, International Development Studies Programme.

Oakley, Peter. 1991. Projects with People. The Practice of Participation in Rural Development . Geneva: ILO/WEP.

Platteau, Jean-Phillipe, and Anita Abraham. 2002. “Participatory Development in the Presence of Endogenous Community Imperfections.” Journal of Development Studies 9 (2): 104–136.

Roche, Chris. 1999. Impact Assessment for Development Agencies. Learning to Value Change. Oxford: Oxfam.

Schönhuth, Michael, and Uwe Kievelitz. 1994. “Participatory Learning Approaches, Rapid Rural Appraisal, Participatory Appraisal: An Introductory Guide.” GTZ Report 248, Roßdorf: TZ Verlagsgesellschaft.

Scriven, Michael. 1980. The Logic of Evaluation. Inverness, UK: Edge Press

Sterkenburg, Jan, and Arie van der Wiel. 1999. Integrated Area Development: Experiences with Netherlands Aid in Africa. Focus on Development Series 10. The Hague: Neda.

Themessl-Huber, Markus, and Markus Grutsch. 2003. “The Shifting Focus of Control in Participatory Evaluations.” Evaluations 9 (1): 92–111.

Vaitilingam, Romesh. 2008. “Be Well… Well-Being: A New Development Concept.” The Broker 12: 4–8.

Williams, Bob. 2008. “Bucking the System.” The Broker 11: 16–19.

Williams, Glyn. 2004. “Evaluating Participatory Development: Tyranny, Power and (Re)politicization.” Third World Quarterly 25 (3): 557–578.

Wilson-Grau, Ricardo, and Martha Nunez. 2007. “Evaluating International SocialChange Networks: A Conceptual Framework for a Participatory Approach.” Development in Practice 7 (2): 258–271.

World Bank. 2008. World Development Report 2008. Agriculture for Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.