9 Negotiated Spaces for

Representation in Mumbai

9.1 INTRODUCTION

There is a well-established discussion on the movement from service provision on the part of governments to collaborative work with the private sector and citizen movements in developing countries (Pierre and Peters 2000; Kooiman 2003; World Bank 2003; Baud 2004). These governance processes provide potential arenas for nongovernment actors to work together with different levels of government. Local city governments see this trend as an opportunity to move policy implementation outwards by involving NGOs, the private sector and community-based organizations (CBOs). This movement includes not only public-private arrangements and public-community arrangements (PPPS/PCPS) but also interorganizational networks—urban platforms of various types that are said to provide better opportunities for citizen groups to promote their claims (Harris 2003). These new arenas, in which local governments request citizens to work with them in determining local needs and in providing basic services, have been termed “invited spaces” (Cornwall 2004). In the 1990s, the debate on governance showed a fairly neoliberal slant; the idea was that the private sector could provide basic urban services more efficiently and effectively than government (World Bank 2003). This view has been partially revised. It is now recognized that under certain circumstances, governments themselves can best provide services (natural monopolies, lack of market demand), and that arrangements should reflect different institutional contexts (World Bank 2003). However, interaction between government and citizens also requires wider issues to be raised—namely, who participates, what processes occur within the interface and what kinds of outcomes are produced.

A current debate, framed in terms of “deepening democracy”, asks whether institutionalizing invited spaces is sufficient to make them inclusive and substantive, allowing for the move to “more just and equitable societies”. In this chapter, we examine what happens within such networks in the context of Mumbai, where a variety of interfaces between local government and citizens exists, and what the potential is for such “invited spaces”.

The increase in invited spaces has taken place at a time when decentralization initiatives in many countries provide local urban governments with mandates for working directly with citizens. There are contrasting views about the value of this process. Some observers consider it to be a sign of increased democracy that the central state is reduced in favor of local arrangements; others feel that this process hollows out the state (Gaventa 2006). The primary question raised by decentralization regards the shifts in relationship between central and local government and the extent to which this provides effective channels for citizens to make their voices heard. Luckham et al. (2000) distinguish four types of “democratic deficits”:

- “Hollow” citizenship (or a lack of substance), where groups of citizens have varying rights and obligations (such as the different family laws that apply to Hindus and Muslims in India);

- a lack of vertical accountability, so citizens cannot hold their governments and ruling elites to account;

- weak horizontal accountability, particularly of local executive government;

- lack of international accountability, as multinational corporations and international organizations bypass national governments.

Our position is that decentralization accompanied by new forms of local representation can produce invited spaces that allow for more inclusive policies and practices and actual engagement with government. However, it remains to be seen whether these spaces offer the possibility to poor people of making their priorities known only as “consumers of services”, or whether they provide the chance to be recognized as citizens with rights.

India provides interesting examples of invited spaces, with decentralization and new forms of local representation through councilors, as well as strong civic engagement with local authorities. The 74th Constitutional Amendment in 1992, which provides for decentralization to urban areas, has been ratified and implemented to different degrees by state governments. In Maharashtra, whose capital is Mumbai, the state government provided for urban local bodies with a mandate for elected councilors and the establishment of ward committees, in which locally elected councilors and administrative ward officers would work together.

We begin this chapter in section 9.2 with contrasting the two major types of invited space at ward level in Mumbai city.1 Although Mumbai has always had an extensive NGO presence, the new initiatives are based on residence (neighborhood level) rather than on membership of social movements, and therefore extend the possibility of people's participation. The first is a programme called Advanced Locality Management (ALM), initiated by the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) in 1996 to improve solid-waste management, which has since grown into a larger movement of citizen-local government interface (Redkar 2004; Zarah 2006). The second involves the processes around local political representation at the ward level, established in the same period as a result of the 74th Constitutional Amendment.

We then proceed by answering the following three questions:2

- Who is “invited”?

- What is the substance and process of partnering?

- What are the perceived outcomes for both “invited” and excluded groups of citizens?

The first question, addressed in section 9.3, is whether Mumbai citizens are differentiated by local government in terms of who is invited to participate in public-community arrangements. In India, recognition of rights in urban areas is based mainly on tenure status. Squatters living in nonregularized slums have no rights to public services, either at household or neighborhood level (Risbud 2003). Earlier, state government policy was to regularize slums, gradually provide services or relocate people to rehabilitation schemes, providing housing and basic services (De Wit 1997; Van Eerd 2008). Currently, this type of policy is being contested through public-interest litigation (PIL) in local and state courts, whose judges have a very different view on squatters3 (Patel et al. 2002); they see them as trespassers on public land, with no rights to basic housing and services. They suggest that, rather than regularizing slums, squatters should be removed. Thus, different groups of urban citizens have different rights according to their tenure status and tenure security in practice, and consequently a different level of access to some forms of cooperation with local government (Ramanathan and Dupont 2005; Ramanathan 2006).

The second question addressed in subsequent sections 9.4 to 9.6 concerns the mandates that local government gives to citizen groups and representatives, along with citizens’ activities, the rights citizens claim and the interfaces citizens themselves prefer to have with local government. What degree of collective action do citizens’ groups have? And is there a significant degree of interface with government, compared to the mandates that elected representatives have?

The third question, addressed in section 9.7, is whether the provision of invited spaces leads to a better quality of urban life. We define quality of life as the extent to which basic needs and rights of local citizens are reflected in activities carried out within the interface between local government and citizens. This includes both their right as consumers to receive basic public services as well as their political right as citizens to codetermine and obtain rights to direct and indirect representation (Kabeer 2002; Fung and Wright 2003). Finally, the chapter conclusions are drawn in section 9.8.

9.2 THE CASE OF MUMBAI

Mumbai is the capital of Maharashtra, one of India's most developed states, and has a population of some 16.4 million (Greater Mumbai or Corporation Area)4. People from the state itself form only about 40 percent of the population; the remainder are migrants from other states, drawn by the growing economy to look for employment in both the top end of the formal labor market and in the lower-end informal activities. The city is a trading hub with strong links to international companies, ICT and creative industries, and (business) services. Currently, two types of economic activity dominate: first, capital-intensive service sectors such as finance and producer services, software development, mass media and residential and commercial real estate; and second, the labor-intensive production of electronics and consumer goods in small-scale workshops within informal settlements. Mumbai started as a manufacturing city with a strong cotton textile industry. Automation and strikes drastically reduced the number of jobs in the 1970s-1980s and formal employment lost in cotton mills was replaced by the expansion of “unregistered production units” to which manufacturing was contracted out (Van Wersch 1992). Displaced textile workers relocated to informal economic activities, within which employment increased from 49 percent of the total workforce in 1971 to 66 percent in 1991 (Pacione 2006).

In contrast, such tertiary sector activities as finance, insurance and real estate services expanded during the 1970s and 1980s, and employment in the sector grew by 43 percent. (Other tertiary sector activities include culture industries, tourism, offshore publishing, data processing for international companies, higher education facilities for the region and labor-intensive medical and nursing facilities.) The urban economy grew by 8 percent in 2004 and 2005. This new private sector is associated with the growth of the middle class and a concomitant consumer lifestyle. The expansion is reflected in growing middle-class housing and suburban sprawl, as well as in civil society groups demanding better services and accountability from the urban local bodies. The expansion of a middle-class lifestyle poses challenges for urban government in expanding housing, services and basic infrastructure to recognized urban citizens. Risbud estimates that 54 percent of Mumbai's population lives in slum areas (according to the 2001 census definitions) (Risbud 2003). The majority of the slums are in the inner-western suburbs, where 58 percent of the slum population is concentrated.5 Housing in squatter areas is treated as illegal, unless residents go through regularization processes.6 Until then, residents have no proof of residence or rights to basic services. This is increasingly an issue, as the middle class and elites are demanding that slums be removed through public-interest litigation because of their illegal status (Patel et al. 2002; Fernandes 2006; Harriss 2007).

Figure 9.1 Mumbai Corporation government: political and administrative wings.

Source: Nainan (2001).

9.3 PRODUCING “INVITED SPACES”

This section discusses the invited spaces that local government in Mumbai has produced to increase the participation of residents in the production of basic services, and in political representation at the electoral ward level.7 The spaces discussed here are the two most important types of invited spaces created in the last decade within local government. They belong, respectively, to the executive and the political wing of the MCGM. The political wing consists of the councilors and mayor, and the executive wing of commissioners and employees of the MCGM (see Figure 9.1). This is interesting, as it indicates the heterogeneity within government, with each wing creating its own patterns of invited spaces.8

Political representation by councilors elected at the ward level was mandated by the 74th Constitutional Amendment in 1992. It directed state governments to implement the legislation, providing a list of twenty-eight functions that could be mandated to local councilors. State governments have implemented the legislation to varying degrees, according to their willingness to shift power to local governments within their states. In Maharashtra, the willingness to localize responsibilities has remained limited, but municipal elections for councilors are held regularly; they form the city council together with the elected mayor.9 The 227 councilors directly elected by voters each represent an electoral ward, and each has an annual budget of Rs. 2 million (US$ 43,478) for development work in his or her constituency.10 They also work together in administrative ward committees, each combining between eight and twenty electoral wards. The administrative ward committee includes elected councilors with one or more ward officers. Three NGO/CBO members can also be nominated to the committee, but this process is tightly controlled by the councilors.11 Currently, NGO/CBO seats on the ward committees are largely occupied by political party nominees.

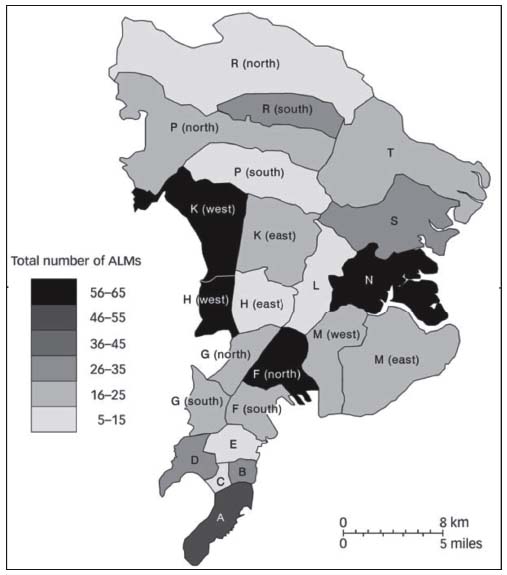

Figure 9.2 Advanced locality management by administrative ward in Mumbai.

Source: adapted from Karmayog Web site (April, 2006).

The administrative wing of the MCGM is responsible for a wide range of services. These include solid-waste management, water supply, drainage and sewerage systems and public roads. It runs hospitals, health centers, primary schools and a local bus service. City planning also resides with the MCGM; it implements development plans and sanctions building proposals (as per development control rules). The planning function is jointly undertaken with the Mumbai Metropolitan Regional Development Authority (MMRDA) and the Maharashtra State Government Department of Housing (MHADA). The former has jurisdiction over the agglomeration area and the latter over citywide infrastructure when foreign funding is obtained.12

The administrative wing has around 160,000 employees. MCGM departments decentralize their activities in the city through ward offices, which bundle the activities for that administrative ward. The largest department in terms of employment is the conservancy department (dealing with solid-waste management), whose staff are also strongly unionized. This situation resembles that in other large cities in India, with similar patterns of staffing and organization.13 Adding employees to this department is often undertaken reluctantly, as it strengthens an outspoken trade union. For this reason, and to cut down on expenditure and reduce deficits, a restrictive staffing policy has been in place since 1995; this has led to a shortage of staff and reduced services. The solid-waste management department developed an alternative strategy to expand services, working directly with residents’ groups in neighborhoods across the city. These are called Advanced Locality Management (ALM) groups. This is the second invited space. Most ALMs were formed between 2002 and 2005 and are unevenly spread across the city (Figure 9.2). Coverage is much stronger in some administrative wards than in others—generally, there are more ALMs in higher-income wards (e.g., K-west and H-west).14 No clear information exists on the number of existing and active ALMs. Discussions with the MCGM indicated that many were formed but subsequently became inactive because leaders stepped down and could not be replaced, or else they consisted of businesses or administrators (not local residents). This explains the difference between the 700 ALMs listed officially and the lesser number found through field studies.

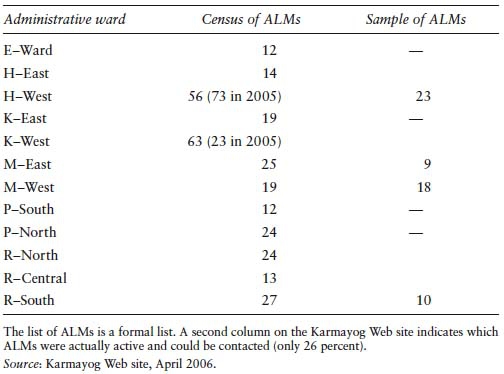

Table 9.1 Census and Sample of ALMs in Selected Administrative Wards in Mumbai*

ALMs have been formed by housing cooperative societies and street-based residents’ welfare organizations.15 They are found extensively in housing colonies (Parsi colony, Tata power colony) or in Christian communities in Bandra (H-West) and Andheri (K-West), building on existing church-related organizations.16 They vary in membership, size and composition (Table 9.1). Most ALMs that are composed mainly of residents have between 100 and 300 members (13 ALMs have between 100 and 200; 14 ALMs between 200 and 300). Eight ALMs are much larger (more than 500 residential members each). Members usually reside in housing society complexes (high-rise buildings), which have mandatory organizations as a platform for undertaking collective measures. ALMs have contrasting views on including political party adherents—some think it creates a good channel for party support for their issues; others want to avoid party politics because it undermines their capacity to push through their own agenda. Therefore, the number of political party members is limited, and only eight out of sixty ALMs have politicians as members. In contrast, two-thirds of the surveyed ALMs have commercial members; 34 percent have up to ten commercial establishments as members; and 20 percent have more than ten. ALM members indicated that they find the private sector provides necessary support in their initiatives.

9.4 MANDATES GIVEN BY GOVERNMENT

The sources of the mandates given by government to the people participating in invited spaces differ. The ward committee mandate is based on the list of activities laid down nationally in the 74th Constitutional Amendment (12th Schedule), from which state governments are free to select specific activities to delegate to ward committees for implementation. The mandate assigned by the Maharashtra government to the ward level consists of the following:

- Redress common grievances of citizens concerning local municipal services;

- make recommendations on existing proposals for expenditures in the ward before they are forwarded to the commissioner;

- grant administrative approval and financial sanction to existing plans for municipal works within the ward committee area up to a limit of Rs. 500,000 (US$ 11,500);

- move on any other powers the corporation may delegate to a ward committee.

This list indicates that ward committees are limited in their tasks to being a platform responding to civic grievances and budgetary recommendations, along with having a small budget to undertake projects.

The mandate of the ALMs was provided by the executive wing of the MCGM, and dealt with solid-waste management.17 Due to the ban on new staff recruitment within the MCGM, the executive wing sought to expand solid-waste management coverage by outsourcing activities. One strategy was to involve housing cooperative societies and their associations in solid-waste management by creating ALMs.18 In practice, ALMs address issues such as garbage clearance, composting, drainage, water supply, beautification, encroachments, road excavation, pothole filling, roads and pavement leveling, surfacing and the management of stray animals.19 Many residents have taken on responsibility for segregating garbage at source, recycling and composting, an activity in which street waste pickers are also involved later. The MCGM supports the initiative by addressing speedily the grievances of residents.

There is overlap between the ward committees and the ALMs in the focus of their mandate as both address issues of solid-waste management. However, ALMs are organized user groups, whereas ward committee members are elected representatives voicing the concerns of all citizens living in the ward. The role of each is distinct, as ALMs are engaged in maintenance and operation services, whereas the ward committees have a small planning and decision-making role.

9.5 CLAIMING “SPACE”

The two types of groups also claim additional space for themselves beyond the mandate provided by government. Councilors have expanded their mandate formally and informally in several ways. Formal claims were established when the councilors persuaded the state and local governments to implement the ward committee legislation; this gives them a say in decisions on maintaining streetlights and footpaths. Informally, the majority of the councilors in north Mumbai responded to individual slum citizens’ demands for provision of basic amenities and housing and protection against harassment by police and goundas (gangs). For women, they provide counseling and assistance on issues such as domestic violence as well as harassment, which are not part of their mandate. All women and most men councilors interviewed in Vogel's study provided such counseling (14 councilors in all). They negotiate regularly on behalf of their constituents; their success is mixed, but their authority is generally acknowledged (Vogel 2007:36). However, Vogel (2007) indicates that councilors do not wish to make such interventions on their part official policy. Councilors were also constrained by having to comply with demands made by leaders higher up in their political party and by real estate developers in their areas with close political connections, so their autonomy was limited (Nainan 2006).

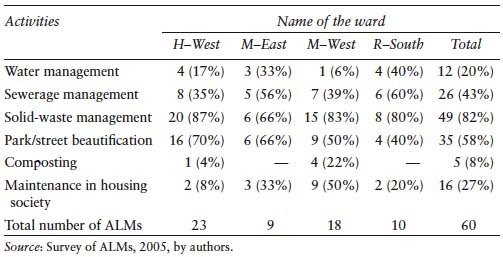

Table 9.2 ALM Activities by Ward (Number and Percent Share of Total Number

The original ALM mandate consisted of monitoring and improving a very visible basic service at neighborhood level—solid-waste management. The MCGM supported this by clearing construction waste from roads and collecting waste more effectively. Most ALMs carry out some activity in this sector. They segregate dry and wet waste and collect waste from house to house. Eighty percent of ALMs are involved in one of these activities, with 10 percent working in collection activities (mainly in M-West) and 90 percent involved in segregation.

However, ALMs have also branched out into other activities, mainly monitoring basic services in their neighborhoods and addressing other issues that members consider important. Table 9.2 shows that the second most widespread activity is “street beautification”, or greening. Many streets still have open concrete drains along the road. The importance of sewerage management is also shown by the fact that more than 40 percent of ALMs have cleaned and closed street drains. ALMs close them by constructing and filling planters over them, and planting bushes and trees along the roads. Almost 60 percent of ALMs have beautified the streets in their own neighborhood. Almost 30 percent of ALMs are also active in maintaining the area around the housing complexes, as a spin-off of greater group interaction and commitment to collective activities. Finally, some 20 percent of ALMs have taken up water management.20 ALMs are concerned with specific issues in their own areas. They exert continuous pressure over a short period of time. Once their objective is achieved, some ALMs become much less active. Others show a “civic” type of mobilization, positioning themselves with broader interests (e.g., participation in local newsletters, involvement in beautification schemes).

Both the invited spaces created by local and state government, councilors and ALMs have gone beyond their original mandates and are actively taking up issues that concern their constituency—be it councilors focusing on low-income residents who feel powerless, or ALMs representing middle-class residents who feel more powerful in their own neighborhoods. Although the ALMs started out with a focus on improving the rights of citizens as “consumers of services”, they gradually realized that they needed a role in “setting the political agenda”. This was reflected in the 2007 municipal elections, where a group of ALMs successfully put forward their own political candidate.

9.6 INTERFACE WITH THE GOVERNMENT— POLITICAL AND BUREAUCRATIC SIDES

Interface with government at the administrative ward level is embedded in the setup of the ward committee, where ward officers and councilors work together. The situation since the 74th Constitutional Amendment has changed fairly radically. Before the formation of the ward committees, councilors visited ward officers to get projects sanctioned and implemented, sharing with them a portion of the money involved. Now, ward officers have to be present at the monthly ward committee meetings and get administrative sanction from the councilors for implementation.21

Relations between councilors and ward officers are usually tense. Elected representatives feel ward officers block effective service to their clients, whereas officers perceive elected representatives as lacking the necessary education to make engineering decisions. Discussions with four councilors in two wards indicated that most councilors felt establishing ward committees had given them more powers.22 Individual councilors listed the following positive changes:

- Clearer budgetary provisions for their wards, with financial monitoring;

- better monitoring of project implementation, with officers reporting on progress;

- coming up with proposals for wards, keeping in touch with the constituency's needs and grievances;

- speedier provision of services;

- rise in status as public official.

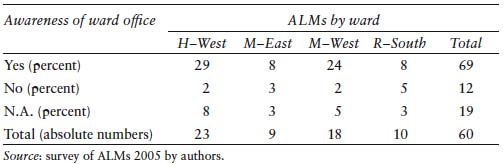

Table 9.3 Per cent Awareness of Ward Office among ALMs

Table 9.4 Percent of ALMs Working with Ward Officers and Councilors in Main

Although the newly acquired powers are limited, some ward committee members are searching for means to expand them. Because budget allocations to the wards are now published, transparency between administrative and elected representatives has increased. The question is whether they will be willing to share it further. Information on ward budgets has not percolated down to either community members or to NGOs that were interviewed, none of whom had any information about 2001 ward budgets.

Councilors also have regular interface with the political wing of government through their citywide council and its standing committees (Figure 9.1). This interface has not been systematically analyzed yet; personal communications suggested that councilor-party boss (citywide) relations are influential in determining allocations of councilors to committees, and are dominated by the party in power.

Box 9.1 Councilor's Perceptions of Relations with ALMs

The councilors complained that they were the elected representatives, and best suited to tackle civic problems. According to them, citizens’ groups can-not think beyond their lanes and are unwilling to listen to reason. They insist on certain priorities, leading to a clash of interests. In the words of one BJP councilor:”Elected representatives are better suited to tackle problems like lack of funds and labor, for example. We understand them but these citizens’ groups are unwilling to listen to reason and insist on a particular work being done immediately” (Times of India, 17 February 2005). According to one NCP councilor:”Citizens create the impression that councilors are incompetent and that NGOs are doing all the work. NGOs are already represented in the ward committees along with the councilors. So the LACCs* are really not required” (Times of India, 17 February 2005). A Congress councilor: “Gang war. That's the only word to describe their working” (Indian Express, 1 July 2005). A Congress party woman councilor: “Icannot do any work because of the ALMs. Please get this harassment stopped” (Indian Express, 1 July 2005).

* Authors’ note: LACCs (Local Area Citizens’ Committees) are an alternative form of ALM since 2004—on a much larger scale (see Karmayog Web site).

The ALM programme also provides regular contact with local government. The interface includes a variety of possible contacts, with different departments that provide services at the city level as well as with area-based ward offices, which carry out activities in one administrative ward only. The survey questioned ALM representatives about the interface with departments, with the ward office in their area, with state government organizations and with NGOs/private companies. Finally, ALM relations with local councilors and party politicians were considered.

Two-thirds of ALMs were aware of the ward office in their area, with no significant difference among the wards covered (Table 9.3). More than half the ALM representatives had visited ward offices for various reasons: to raise grievances and complaints (72 percent); to seek help (63 percent); and to obtain expert advice (62 percent). They also held ALM meetings with ward officers and councilors at the ward office. According to the mandate, these should be held once a month. However, practice varies according to the interest the ward officer takes in ALMs.

ALMs also prefer to work with the executive side of government. They work almost twice as often with the ward officer as with the ward councilor in their main activities of solid waste management, sewerage and water issues (Table 9.4).

ALMs also work with specific departments (bureaucrats) of the MCGM at the city level. Almost half the ALMs had contacts with the sewerage department, 70 percent worked with the solid-waste department, 34 percent with the garden department, and 10 percent with the water department. ALM leaders indicated that trust had gradually built up with the corporation officers, improving the responses they received from officers about complaints. The ALMs also indicated that their experiences with higher officers at the corporation level were more cooperative than at the ward level. Although awareness of ward committees among ALMs is high, it does not translate into working with ward committees or councilors to address issues (Table 9.4). Two-thirds of ALM leaders contacted councilors; however, only half of them visited the councilor occasionally on issues in which the councilors have some role. The ALMs’ experience with politicians at large is not one of cooperation; only 20 percent work with councilors.

Reasons given by the ALM representatives include the fact that they feel politicians are not interested in them and do not know enough about ALMs; some also feel that politicians see ALMs as competitors. Newspaper accounts certainly suggest that some councilors feel threatened by ALMs.

The ALMs were also asked about possible requests for bribes received from government or elected officials. This turned out to be low: 7 percent experienced requests for bribes from politicians at various levels and 8 percent from corporation officers at various levels. In contrast, when asked to identify problems faced by the MCGM, 52 percent of those interviewed felt the problem lay in corrupt practices of the corporation.

The majority of ALM representatives was very positive about current changes in the MCGM and optimistic about its future. Sixty-two percent identified the main problem of the MCGM as being its coordination with different agencies; 57 percent of those interviewed believed it was due to the quality of municipal staff; and half the respondents stated it was to do with MCGM politics.

The discussions above indicate that slum citizens tend to approach elected councilors to make demands, whereas within the ALMs there is a preference for working with the executive wing and its various departments. As ALMs more generally represent higher-income areas and groups, this suggests a difference in constituencies between the two invited spaces.

9.7 EXPANDING SPACES, EXCLUDING OTHERS?

The third question concerns changes in the exercise of citizenship through invited spaces in neighborhoods where ward committees and ALMs are active. Ward committees generally see NGOs and CBOs as representatives of residents with complaints and protests, so relations are confrontational. They cooperate with a few CBO organizations using service delivery strategies, which partner with local government in sectors such as education, health and solid-waste management.23

Box 9.2 AGNI's Actions against Municipal Workers’ Union

On the eve of Diwali, in October 2000, 140,000 workers from the MCGM went on a two-day strike called by the largest union of municipal workers* after the mayor of Mumbai refused union demands for higher bonuses and ex-gratia payments. This strike hampered city functioning, as taps dried up, garbage piled up and municipal hospital staff joined the strike (Indian Express, 26 October 2000). To control the growing city disruption, nearly 200 councilors decided to support the strikers’ demands by passing a unanimous resolution to pay 65 percent of the bonus to municipal employees. However, AGNI's vice-chairman, a member of the Indian Administrative Service and a former municipal commissioner and chief secretary of the Maharashtra government, approached the High Court of Bombay asking for urgent interim relief on his petition, admitted in 1997, that challenged high salaries and bonuses to civic employees.** The Bombay High Court restrained the MCGM administration from giving in to worker demands and struck down the councilors’ resolution. The municipal workers union leader was reported to have challenged the “…citizen groups and non-governmental organizations to lift garbage from the roads … no one will be available as nobody has the stamina to do the kind of work that BMC workers do” (rediff.com/news, 2000). Under similar conditions the following year, AGNI and member ALMs pressured state government to end the municipal workers’ threat to strike again, based on essential services maintenance(Times of India, 20 July 2001). The union did not strike and since then has only issued threats or undertaken one-day strikes, keeping essential services untouched.

*The municipal Mazdoor union, led by Sharad Rao with George Fernandes as its leader, who had by then joined the BJP-led coalition government and was defense minister in 1998. BJP has an alliance with the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra.

**All higher-level government cadres are only drawn from a group of individuals who have undergone a specialized training and exams of the Indian Administrative Services. These bureaucrats are called IAS officers.

Source: Authors’ case study.

Generally, NGOs do not work with the political (deliberative) wing of the MCGM at city level, and NGO relations with ward councilors are full of conflict and confrontation. NGOs perceive councilors as opportunists, corrupt and sometimes criminal. NGOs recognize that they are a threat to the councilors’ power base and are perceived by them as competitors.

NGOs do work with the executive arm of the MCGM at city level. Most NGOs associate with specific departments for services at ward level. Organizations that have good relations with central departments of the MCGM may have less close or even conflictive relations at the ward level. This means that councilors and ward officers prefer not to expand the space for middle-class citizens organized in NGOs or ALMs. Councilors consider low-income residents their main constituency. These residents need their political clout to gain access to housing and basic services. However, the councilors want to keep them dependent and be the “brokers” through whom resources are channeled—e.g., the Slum Adoption Programme (Desai 2006).

The main interface ALMs have with NGOs is with the Action for Good Governance Network India (AGNI), an NGO established in 1999 that functions as an advocacy group on local governance issues in Mumbai. Among its key leaders are ex-bureaucrats and media people. AGNI was assigned an informal role in facilitating the formation, networking and capacity building of ALMs and ALM networks. Thus, right from the beginning, ALMs came into contact with AGNI and often joined the network, which was further strengthened as AGNI started representing the political voice of middle-class citizens at city and state level. Among its campaigns, AGNI's efforts to scuttle an MCGM workers’ strike brought it into the limelight (see Box 9.2).

In dealing with the government, ALMs prefer not to deal with the political wing but, rather, strongly prefer the executive wing at either city or administrative ward level. The ALM survey showed that 70 percent of the respondents perceived positive results in their quality of life, in terms of cleaner roads, regular garbage pickup, more green spaces and organized groups. This suggests that they are able to claim more rights to “good service space” as user groups.

However, exclusionary processes are also taking place. In wards where ALMs are active, people from slum areas are usually not included, despite the original intent of the corporation's solid-waste-management department that they would work together in improving solid-waste management. However, slum representatives (youth who were interested in taking up cleaning activities) were said to feel intimidated at ALM meetings, because they are conducted in English and require reading and writing proposals. ALMs are also based on voluntary labor and time, something that slum dwellers usually do not have in abundance.24 ALMs in other wards have lobbied to exclude groups from their neighborhoods, particularly street hawkers.

In the ALM survey, examples were found of exclusion as well as efforts to include marginalized groups—hawkers were excluded from the beachfront but efforts were made to find them jobs in maintaining the local stadium. The general use of public-interest litigation in India at this time, exerted by middle-class groups in various cities in order to “clear up” public spaces, suggests that it will be important to analyze the relative strength of both the increasing inclusion of middle-class citizens in interfaces with the executive side of government and the exclusion of vulnerable groups who are not well represented (see also Ramanathan 2006; Fernandes 2006).

9.8 EFFECTS ON SERVICE DELIVERY AND POLITICAL RIGHTS

This section deals with the question of what the outcomes of invited spaces have been for service quality and for the political rights of different groups of residents. In the middle-class (and elite) areas where the majority of ALMs were formed, ALM respondents have indicated that service delivery has improved (70 percent of respondents). In particular, the responsiveness of local MCGM employees is greater than before. If we look at citizenship rights, there is a clear expansion of spaces—beyond the mandate and interface provided in the initial invited spaces. Through collective action in ALMs, middle-class citizens are opening up further “negotiated spaces” in two ways. They are claiming more and better services on a priority basis, and are organizing to exclude groups from their neighborhoods they feel are “unwanted” (slums, hawkers, unorganized economic activities). Second, they are moving from “user” to “chooser” groups as citizens, claiming a larger political space, although this is heavily contested. In fact, one group of ALMs successfully put forward their own candidate for local elections in early 2007.

The ward committees have expanded the space for residents in all electoral wards to approach elected representatives locally, and many have done so, particularly those with personal problems and those facing deprivations in their habitat. Although the current mandate of the ward committees in providing and monitoring service delivery remains limited in terms of the areas where they have a say (footpaths, road lighting) and the size of the projects over which they have a say, it has clear potential for building up participatory forms of local governance closer to residents in such a large city.

9.9 CONCLUSION

Coming back to the main question of this chapter—namely, whether invited spaces provide effective channels for citizens to make their voices heard—we draw the following conclusions. There are contrasting invited spaces in Mumbai, which provide effective channels for particular social constituencies. ALMs provide channels for middle-class residents to deal directly with the executive wing of local government; the ward committees provide effective channels for vulnerable groups to individually address local government to improve their quality of life. The opportunity for collective action of the ALMs does not exist for councilors and ward committees. The political parties at the city level limit councilor autonomy in certain areas and keep them, as well as their constituencies, dependent on higher political authorities.

The widening space of the ALMs is reflected in the negotiating process in the interface between the ALMs and the executive wings of local government. The mandate provided is being expanded and widened to include other political spaces at higher scale levels. Its effectiveness can be deduced from the backlash of political representatives, who fear a diminishing of their power.

Finally, we find two models of what we prefer to call “negotiated spaces”. For low-income vulnerable and poor groups of citizens, the “political space” remains one through which they are able—to some extent—to negotiate rights. For middle-class citizens, an “executive space” is opening up, which increases their direct negotiating power with local government and provides a basis for collective organization, expanding their rights at the city level. To what extent do we find a “democratic deficit” in these contrasting models? It is clear that different groups of citizens have different rights and are dependent on the political will of representatives working for them. Vertical and horizontal accountability has increased for the middle class, as citizens can now hold their government to account to some extent.

NOTES

1. We are focusing particularly on initiatives linked to localities (wards, neighborhoods) within the city rather than on city-level initiatives, because the latter tend to be dominated by large NGOs linked to their specific networks (churches, social movements, political parties), whereas the former are based on the residential status of the participants.

2. These questions are answered on the basis of original field research in Mumbai in the period 2004–2007. The research methodology underlying this research combines surveys with in-depth interviews with governance and nongovernance actors and slum dwellers, and has been extensively described in Baud and Nainan (2008).

3. Public-interest litigation (PIL) is being used by middle-class citizens to end government's condoning of squatter settlements. In Mumbai, government has ruled that squatters living in the city prior to 1995 (and later 2000) can be regularized in order to increase their tenure security. Residents who have squatter settlements in their neighborhoods are pursuing the government to actually adhere to its own rules and to remove any squatters who are there illegally (See Patel et al. 2002).

4. The Mumbai metropolitan region has a population of almost 24 million people (Sivaramakrishnan et al. 2005).

5. Pavement dwellers andchawls—i.e. premises for rent constructed originally by factory owners—are included in slums. Slums are not a homogenous category, ranging from areas where pavement dwellers live, to chawls and zapadpattis (See Risbud 2003).

6. This has to be done under the auspices of the state Slum Development Authority.

7. Electoral wards are the smallest unit of government, represented by councilors brought together in the city council (in Mumbai there are 227 wards). Administrative wards in Mumbai refer to the next largest unit in the city (24 wards), and are utilized as areas for the implementation of public services. Several administrative wards have been grouped together to form 16 ward committees.

8. The heterogeneity within local government is the result of the constant jockeying for power and resources between the two arms of the MCGM. Their conflict is rooted in the relationship between the state and local government. Although the 74th Constitutional Amendment aimed at strengthening local government, power within the MCGM is with senior executive officers appointed by the state government. See Pinto (2008). Competition is stronger when different parties rule the city and the state and, largely, this has been the case since 1985. Shiv Sena has ruled the MCGM, whereas the state is ruled by Congress. Thus control of local government by state-appointed officers is resented by locally elected representatives.

9. The state has designated less than half the possible activities to urban local bodies, and has held three municipal elections since 1992.

10. Each councilor is paid a sitting allowance for attending MCGM meetings (Rs. 2,700 per month). They also get a free bus pass to travel on the MCGM-owned public transport utility, BEST, within the city during their term of office.

11. Some wards have merged their ward committees, making a total of 16 rather than the full number of administrative wards. See Vogel (2005) and also Nainan (2001).

12. The MCGM has a yearly budget of Rs. 12,000 crores (about US$ 300 million) and more than 150,000 regular employees. It is considered the largest municipal corporation in India. Its revenues come from patent and property taxes in almost equal proportion, and it is one of the few corporations that generate the major part of their revenues internally. See Rath (2006).

13. Ward offices include only the administrative side, whereas ward committees include both councilors and ward officers; these have been grouped together to form 16 ward committees. See Baud et al. (2004).

14. Insiders indicate that this has to do with the willingness of private citizens or private-sector enterprises to take up their leadership, and the general income levels in the area. ALMs tend to die out when they depend only on a single leader, or when local problems have been solved to their satisfaction.

15. An ALM covers a neighborhood or street with about 1,000 citizens, and is registered by the ward office.

16. ALMs were also promoted by organizations such as Action Good Governance Network India (AGNI), an advocacy NGO with close ties to Bombay First, a lobby of the new commercial sector.

17. Solid-waste management is one of the major activities of local governments, and absorbs a major part of their staff and finances.

18. An alternative model was developed for low-income areas, called the Slum Adoption Programme, which was directed towards more effective solid-waste management. See Desai (2006).

19. See the AGNI Web page on ALM activities at www.agnimumbai.org.

20. This included various activities such as dealing with leaking water pipes and with water shortages, and an awareness campaign around water issues.

21. The sharing of money for getting projects cleared or from cuts from contractors still remains part of the process.

22. Four councilors were interviewed for this study, two from each ward. Three were from different political parties, the fourth was an independent, and one of the four was a woman. In one ward, the majority of the councilors were Shiv Sena, whereas in the other ward, the representation was across the board.

23. Two of the three sectors where NGOs partner with the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) (or Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM))—health and solid-waste management—are programmes with international funding, containing national guidelines prescribing NGO participation. Even with the executive wing of the BMC, NGO participation is easier said than done. NGOs are included at the implementation level only under severe prescriptive conditions.

24. Such slum areas now fall under the Slum Adoption Programme (SAP) established in 1998 as part of a cleanliness drive by the MCGM. Within SAP,CBOs are treated as commercial entities, supported by municipal financing for carrying out solid waste management collection and segregation activities (Seema Redkar, personal communication, May 2006).

REFERENCES

Baud, Isa. 2004. “Learning from the South; Placing Governance in International Development Studies.” Inaugural Lecture. University of Amsterdam, June, 35 pages.

Baud, Isa, Johan Post and Christine Furedy. 2004. Solid Waste Management and Recycling: Actors, Partnerships and Policies in Hyderabad, India and Nairobi, Kenya. Dordrecht, London, New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Baud, Isa, and Navtej Nainan. 2008. “Negotiated Spaces for Representation in Mumbai: Ward Committees, Advanced Locality Management and the Politics of Middle-Class Activism.” Environment and Urbanization 20 (2): 483–499.

Cornwall, Andrea. 2004. “Introduction: New Democratic Spaces? The Politics and Dynamics of Institutionalized Participation.” IDS Bulletin 35 (2): 1–10.

Desai, Padma. 2006. “Slum Adoption Programme.” IDPAD Project Paper. Mumbai: New Forms of Urban Governance.

Fernandes, Leela. 2006. India's New Middle Class: Democratic Politics in an Era of Economic Reform. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Fung, Archon, and Erik Wright. 2003. Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovation in Empowered Participatory Governance. London: Verso.

Gaventa, John. 2006. “Triumph, Deficit of Contestation? Deepening the ‘Deepening Democracy’ Debate.” IDS Working Paper 264. Brighton, Sussex: University of Sussex.

Harris, Nigel. 2003. “Globalization and Management of Cities.” Economic and Political Weekly 48 (25): 2535–2543.

Harriss, John. 2007. “Antinomies of Empowerment, Observations on Civil Society, Politics and Urban Governance in India.” Economic and Political Weekly 57 (26): 2716–2724.

Kabeer, Naila. 2002. “Citizenship, Affiliation and Exclusion: Perspectives from the South.” IDS Bulletin 33 (2): 12–23. Brighton, Sussex: Institute of Development Studies.

Karmayog. 2006. “Mumbai Information.” Accessed in April 2006, http://www.Karmayog.com.

Kooiman, Jan. 2003. Governing as Governance. Palo Alto, CA: Sage.

Luckham, Robin, Anne-Marie Goetz and Mary Kaldor. 2000. “Democratic Institutions and Politics in Contexts of Inequality, Poverty and Conflict: A Conceptual Framework.” IDS Working Paper 104. Brighton, Sussex: Institute of Development Studies.

Nainan, Navtej. 2001. “Negotiating for Participation by NGOs in the City of Mumbai.” MSc Thesis. Rotterdam: Institute of Housing and Urban Development Studies.

Nainan, Navtej. 2006. “Parallel Universes: Quasi-Legal Networks in Mumbai Governance.” Paper presented at the seminar on Urban Governance in an International Perspective, January 7, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Pacione, Michael. 2006. “Mumbai.” Cities 23 (3): 229–238.

Patel, Sheela, Celine d'Cruz and Sunder Burra. 2002. “Beyond Evictions in a Global City: People-Managed Resettlement in Mumbai.” Environment and Urbanization 14 (1): 159–172.

Pierre, Jon, and Guy Peters. 2000. Governance, Politics and the State. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Pinto, Marina. 2008. “Urban Governance in India—Spotlight on Mumbai.” In New Forms of Urban Governance in India: Shifts, Models, Networks and Contestations, edited by Isa Baud and Joop de Wit. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Ramanathan, Usha. 2006. “Illegality and the Urban Poor.” Economic and Political Weekly 51 (22): 3193–3197.

Ramanathan, Usha, and Véronique Dupont. 2005. “The Courts and the Squatter Settlements in Delhi—or the Interventions of the Judiciary in Urban Governance.” Paper presented at the IDPAD seminar on Initiating New Forms of Urban Governance, 10–11 January, New Delhi.

Rath, Anita. 2006. “Fiscal Federalism and Megacity Finances: The Greater Mumbai Case.” Paper presented at the conference on New Forms of Urban Governance in Indian Megacities, June 20–21, New Delhi.

Redkar, Seema. 2004. “New Management Tools for the Solid Waste of Mumbai: Some Concerns.” Paper presented at the IDPAD seminar on Initiating New Forms of Urban Governance, January 10–11, New Delhi.

Risbud, Neela. 2003. “The Case of Mumbai.” Report for Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements 2003. Delhi: School of Planning and Architecture.

Sivaramakrishnan, K. C., Amitabh Kundu and B. N. Singh. 2005. Urbanization in India. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Van Eerd, Maartje. 2008. Local Initiatives in Relocation: The State and NGOs as Partners? New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Van Wersch, H. 1992. The Bombay Textile Strike, 1982–83. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Vogel, Tara. 2005. “Post-74th Constitutional Amendment Governance in Mumbai: How and to What Extent Does This Brand of Decentralization and Affirmative Action Benefit the Intended?” MSc thesis, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Vogel, Tara. 2007. “Reservation in India and Substantive Gender Equality: A Mumbai Case Study.” International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities and Nations 7 (5): 27–42.

Wit, Joop de. 1997. Poverty, Policy, and Politics in Madras Slums: Dynamics of Survival, Gender and Leadership. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

World Bank. 2003. World Development Report 2 003. Delivering Services Effectively for the Poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zerah, Marie-Helène. 2006. “Assessing Surfacing Collective Action in Mumbai—a Case Study of Solid Waste Management.” Paper presented at workshop on Actors, Policies and Urban Governance in Mumbai, February 23, Mumbai.