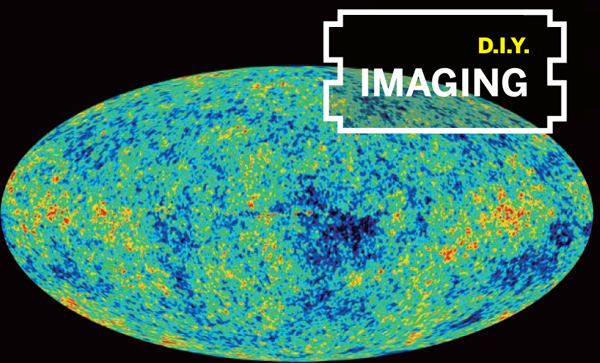

PRINT THE UNIVERSE

This thermograph of the universe as it appeared 13 billion years ago makes a great poster.

Photograph by NASA/WMAP Science Team

Make gigantic posters with a free web service.

The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observatory is a 1,850 pound, 15-foot-diameter satellite that orbits the Earth at a distance four times farther than the moon. It detects 13-billion-year-old temperature fluctuations from the early universe by recording microwave radiation from 379,000 years after the Big Bang. These fluctuations are the seeds from which galaxies eventually formed.

I’ve always wanted to print out some of the amazing WMAP images (map.gsfc.nasa.gov/m_or.html) but I couldn’t find a way to print them large enough to do them justice. Then I discovered the Rasterbator (homokaasu.org/rasterbator/).

This web (and PC standalone) PDF-creating application can take just about any image and make it as large as you want, even completely covering an entire wall. To use it, make sure your image is under the 1-megabyte limit, and then upload it. I used Macromedia Fireworks to compress my file enough to squeak it in under the limit. After it uploads, you can crop and size the image. For my wall I used U.S. Letter (8½"x11"), horizontal, 6 by 4 sheets (24 sheets) for a total poster size of 66"x34".

In the final options, you can choose outlines for the poster to make trimming easier, dot size, and color (black and white, monochromatic, multicolor). I chose the smallest dots, multicolor, and didn’t need outlines. Once you finish, you’ll get a PDF to print out.

Phil Torrone ([email protected]) is associate editor of MAKE. Read his blog at makezine.com.

You can ask friends and even strangers in far-off locales to do the filming.

Photograph of Michael W. Dean by Newtron Photo

MAILBOX MOVIE

Make a movie that’s shot in many locations around the world without leaving your house.

By using the internet and postal mail, you can create a “Mailbox Movie.” Getting other people to shoot your movie for you, and having them send you the tapes when they’re finished, lifts a burden from your shoulders so you can concentrate on writing and editing.

This process works especially well for documentaries, but could conceivably be done with a drama or comedy.

It works well for documentaries because there is less “directing” involved.

A well-shot interview is a well-shot interview. Most of the “directing” in documentaries is really done in the writing and editing. (Well, also in the choice of interviewees, and in the questions you ask them.)

Making It Happen

In 2002, I made a movie called D.I.Y. or DIE: How To Survive as an Independent Artist (diyordie.org). This documentary is an exploration of the D.I.Y. ethic in art. The movie not only covered this concept, it utilized it throughout the production.

I didn’t have the money to fly a crew to all the other shooting locations involved. So I asked friends (and strangers) in these locales to do the filming, to my specifications, and mail me the mini-DV tapes. I shot the local interviews myself, gathered all the music, still photos, and archive footage (I did a lot of this over the internet and through the mail also). I wrote the outline for the film and the copy for the narration. Then I narrated the film in a friend’s studio. My editor, Miles Montalbano, and I made the tapes and all the other stuff into a kick-ass, great-looking movie.

Open Source Camera People

There are over 10 million mini-DV cameras in the world. Most people who have them have no idea what to really do with them and would love a little direction.

Most of the shooters on our project were kids who had read my filmmaking book, $30 Film School (30DollarFilmSchool.com), and had sent me unsolicited DVDs of the projects they’d made as a result.

New filmmakers are always interested in getting experience in higher-profile films. It’s a winwin situation. I got the interviews shot quickly, for free, and the camera people got a credit in a cool film that got bigger distribution than they would be likely to get by themselves at first.

You can easily find help. Post on craigslist.org (you can post on the specific board for the city you want to film in). Also try res.com or my own web board at kittyfeet.com/phpBB2 (and yes, that’s case sensitive). And shootingpeople.org has a daily email list with call boards for both New York City and the U.K. You can also post on boards (both web boards and old-school cork-and-thumbtack boards) at film schools around the country. Try contacting film schoolteachers. Even community colleges usually have a television production or media department.

Logistics and Such

When making a mailbox movie, you should send emails to the people doing the interviews for you with all the info they’ll need. Give them the phone number and address of the people they’ll be interviewing, what time they should get there to set up, and how long they’ll have. And you should phone the interviewees yourself the day before the interview to reconfirm. This is your job, not the job of the person working for you for free. Don’t leave anything to chance. This may seem like a lot of work, but it beats having to fly there and do it yourself.

Giving Instructions

Give your shooters a short description of how you like to frame and light people. Email them some stills. Better yet, if you have time, send them a film you’ve shot. Make sure you tell them what aspect ratio you’re shooting in, and make sure they know how to get good sound. I usually recommend they bring headphones to check the audio, and recommend the Audio-Technica Omnidirectional Lavalier Microphone, model ATR-35S. There are tons of them new on eBay for about 30 bucks a pop. And they get great sound, better than some $300 mikes.

I had a cut-and-paste document for telling people all this. I also emailed the shooters release forms for themselves, and for the interviewees, and for any helpers. (You can download the ones I used at the bottom of 30DollarFilmSchool.com.) And don’t forget to send them the list of the questions you want them to ask.

A week or so later, you should get a package in the mail from each interviewer with a tape of the interview and also all the signed releases.

Covering Your Ass

I also asked the shooters to make digital copies of the tapes as a safety measure before mailing them to me. This was very useful, as one of the 30 tapes got damaged in the mail, and the guy was able to overnight me a replacement. Without this forethought, we would have been screwed.

Also, you should put in your cameraman release form that they are not allowed to use the footage for any of their projects. It would be very embarrassing if this happened, would probably anger the interviewees, and possibly hurt your name as far as filming cool people later. The exception might be where people have already shot the footage, and you’re using it as archive. This is negotiated on a case-by-case basis. But if you’re getting them to let you use that stuff exclusively, you’d better have some kind of quid pro quo for them. It doesn’t have to be money, but you’ll have to offer them something they want.

The first rule of no-budget negotiation is to be able to figure out what people want. Everybody wants something. Maybe you have it. Or can get it. Hint: It’s not always material.

Michael W. Dean lives in East Los Angeles. He is the author of a no-budget digital filmmaking book, $30 Film School. Michael’s new film is called Hubert Selby, Jr.: It/ll Be Better Tomorrow. View the trailer at CubbyMovie.com.

CHEAP SHOT

Turn a $10 single-use camera into a $20 reusable digital camera.

After you take 25 pictures with Dakota’s single-use digital camera ($11), you’re expected to take the camera back to the place you bought it and get the images developed. The camera is not returned to you. I bought one, and after opening the package, I noticed a blue sticker on the camera that said, “Camera does not connect to home computers.” Whenever someone says that something cannot be done, that always gets me in the mood to prove them wrong.

The interface (hidden under the sticker) looked fairly simple, and I went online to see if there were any electronic schematics that would define it more clearly. Much to my surprise, I found a website (cexx.org/dakota/) that said it was as simple as cutting a USB cable in half and soldering the four wires onto the interface. The necessary software had already been created as well!

With the cost of this camera being so low, it’s perfect for places I wouldn’t dream of taking a more expensive camera. I intend to use it for kite aerial photography (see MAKE Volume 01, page 52) this spring, and in the summer I plan to use it for timed photos from the front of a kayak.

The packaging indicates that this camera can be purchased at Wolf Camera, Kits Camera, Ritz Camera, The Camera Shop, and Inkleys Camera. This camera comes in a couple of different models, but I chose the older style because of the lower cost and because I didn’t need an LCD screen.

Most of my supplies came from RadioShack. I used a 25-watt electric soldering iron, with standard rosin core solder (0.39 dia) for this project.

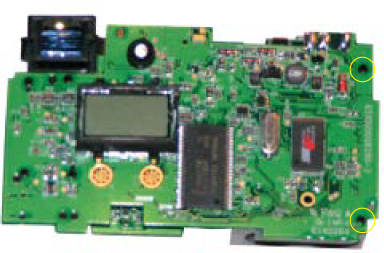

Fig. 1 Converting the Dakota single-use digital camera into a reusable digital camera involves attaching a USB cable to the camera’s interface. Don’t be fooled by the sticker that reads “Camera does not connect to home computers” — it’s not true, and the sticker covers a screw you need to remove to open the camera. Once you solder on the USB cable, you’ll need to download some free software that lets you extract the photos stored on the camera.

Photography by Charles C. Hoffmeyer

The wire strippers should be able to handle a 22-gauge wire or smaller. For the USB cable, I purchased a car charger on clearance from RadioShack ($2.99), which had a USB cable in the packaging. Avoid high-cost USB cables to keep this project as wallet-friendly as possible.

Procedure

Open package and remove front housing. The purpose of taking the camera apart is to get access to the interface so you can solder the USB wires to it. Start by removing the batteries from the battery compartment. On the bottom of the camera, you will notice two screws (Fig. 2).

TOOLS:

Dakota single-use digital camera

Soldering iron with solder

Small Phillips screwdrivers

Wire strippers

A USB cable

Electrical tape

Hot-glue gun (optional)

Hot glue (optional)

Remove these screws. Now look at the right side of the camera. Remove the sticker saying, “This sticker should only be removed by a Big Print Central Sales Associate” and remove the screw. Pull the camera apart; it will split into two pieces.

Fig. 2

Remove rear housing. Fig. 1 (top photo) identifies six locations where the screws should be removed (yellow circles). Remove those screws, and pull the rear housing off the circuitry.

Remove battery compartment. Fig. 3 identifies two screws that need to be removed. Fig. 4 identifies two more screws to remove. The wire holding the shutter switch is very thin, so be careful not to let it wobble around too much, or you will make more work for yourself re-soldering the wire back in place. Gently pull the two pieces apart (Fig. 5). The interface will be clearly visible on the left-hand side of the lower assembly.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Strip wires on USB Cable. I used the cutting tool on my wire strippers to do this. Regular scissors would work as well. Gently strip back the outer rubber cover and shielding. Leave yourself about an inch to work with the four wires within the USB cable. Strip the four wires so that between half to three-quarters of an inch of color is visible.

Solder the wires to the circuit board.

Fig. 6 shows how the wires should be connected to the board. Because of the thinness of the wire, I found that it was easier to solder the wires by using the soldering iron to put solder on the wire directly and letting it cool. Then set the soldered wire directly on the circuit board and touch the iron to the wire. Make sure the wires do not wiggle and touch. I covered them with electrical tape on top and bottom and then also wrapped the remaining exposed cable with electrical tape (Fig. 7).

Reassemble the camera. Perform the disassembly steps in reverse to put the camera back together.

Use hot glue to fill in empty space. I used hot glue to fill in the remaining empty space around the interface connection after reassembly because I accidentally pulled on the cable too hard at first, and the wires I soldered in place broke off. After the glue dried, I finished wrapping the cable with electrical tape to ensure stability.

Install software on computer. Visit cexx.org/dakota/ and download the software for your camera. With the Windows software, be sure to read the “readme” notes included with the software. There is a specific process for configuration before connecting the camera to the computer.

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Connect camera to computer. If you did everything right, the camera will power up and the rear text LCD will show “PC” to indicate that the computer is connected. Congratulations! You now have a multiple-use digital camera for under $20!

Charles Hoffmeyer ([email protected]) is a programmer/analyst for the Michigan Department of Information Technology.