CLOTHESLINE RACES

This high-flying contest tests robotic prowess, creativity, and sense of humor.

Last November, a group of makers took their robots to Minneapolis’ Hack Factory hackerspace. These robots didn’t roll around on the floor following a line, fighting, or picking things up. Instead, they did one thing: move along an ⅛”, 100’ length of woven steel aircraft cable and, upon reaching the end, return to the starting point — as fast as possible. It was a Clothesline Race, a contest invented by the hackerspace’s founding president, Mike Hord.

Hord’s fascination with this sort of race goes back more than 20 years. As a child, he was obsessed with a Cub Scout event called Space Derby, in which toy spaceships run along cords, powered by rubber bands and propellers. Space Derby isn’t nearly as popular as the Scouts’ Pinewood Derby, in which Scouts build and race wooden cars, a fact that Hord attributes to the Space Derby’s greater complexity. “To keep the playing field level,” he says, “you need to provide a more complete kit and allow less leeway, because the task is harder and there are so many more ways to solve it.”

But Hord came to realize that what was a liability for a kids’ event made for a fascinating challenge as an adult. When he helped found the Hack Factory, he saw his opportunity to organize his own Space Derby — upgraded for more sophisticated, adult makers.

In a Clothesline Race, the track is a length of rope or cable, stretched taut and level, with a metal plate at either end. Unlike the Cub Scouts’ Space Derby, there is no kit. Your racer can use virtually any technology, so long as it’s safe. Depending on the specific race’s rules, racers can be propelled by anything from Lego Mindstorms servos to model airplane props to Estes rocket engines.

Some of Hord’s ideas have included a can-and-pipe Stirling engine (see MAKE Volume 07, page 90) and a wi-fi-enabled crawler. “I’ve also had ideas for a brachiating racer built into a stuffed monkey, a gyro-stabilized racer that balances on the wire, and a propeller that somehow uses the wire as its hub,” Hord says. “Or at the other end of the spectrum, designs that are as simple as possible: a bristlebot-like microracer, a couple of balloons with a straw, and something based on a rat trap.”

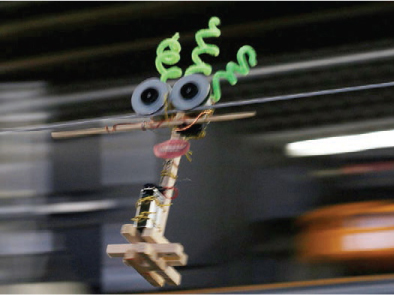

John Scherer

A. Plush “Fanby” ferret.

B. Battery packs, 9V powering the propellers and 4x AA for everything else.

C. Propellers mounted on DC motors (shown unwired).

D. Banner QS18VN6CV45 photoelectric proximity sensor.

E. Tamiya gearbox.

F. Coroplast wings, cosmetic.

G. Arduino Duemilanove with Adafruit Motor Shield.

H. Coroplast tail, cosmetic.

I. Rear support, Tamiya girder.

J. Integrated circuit storage tube.

BUILDING A RACER

Hord’s latest racer looks like a ferret suspended underneath an airplane, an ode to a couple of early xkcd comics. It consists of an Arduino, an Adafruit Motor Shield, a Tamiya gearbox, a few motors, and a Banner proximity sensor. Hord salvaged most of the parts. “The propellers came from hardware store balsa gliders and their motors from some of my daughter’s outgrown baby seats,” he says. The spine is an IC storage tube, and the wings are pieces of Coroplast boxes salvaged from Hord’s office dumpster, where he also found the sensor.

Each clothesline racer consists of three basic components: a motivator, a direction-reversing mechanism, and something that couples the first two components to the wire. The simplest design is a motorized wheel with a switch that reverses current to the motor when the racer hits the end plate. But if the racer is traveling too fast, it’ll smash to pieces when it hits. Some participants program their racers to slow briefly before they reach the plate. Others add springs or bumpers to reduce the impact damage.

Clothesline races are so experimental that they often turn into impromptu improvement-and-repair sessions, with participants hunching over soldering irons and glue guns between heats, trying desperately to fix bugs and eke out more speed. If you participate, make sure to take your tools to the race.

RUNNING A CLOTHESLINE RACE

To hold a race, all you need is a long, taut wire (racers can get trapped if it sags too much). With a lot of beginners participating, skip the requirement that racers travel back to the starting point. Conversely, with advanced makers, you can add complexity: hang the wire at a slant, or require the robots to drop things or pick them up.

Peter Tirsek

To save time, make the wire available for participants to test out their racers in advance. Even a relatively modest race with a half-dozen contestants can take several hours. Each heat takes only a minute, but a racer won’t necessarily be ready to roll when its turn comes up. Race-day tinkering and spur-of-the-moment creativity are part of the fun.

Safety is paramount. You don’t want anything that could explode, start a fire, or spin off the wire into the spectators. “On our last race day, we had one racer that covered the course in a bit more than five seconds, pushing 25mph,” Hord recalls. “That racer had two model aircraft propellers on it, and when it hit the plate it exploded into quite a few big chunks, two of which were essentially spinning plastic knives. Nobody was injured, but we learned a lesson in caution regarding having people too near the end of the course.”

![]() ON THE LINE Scott Hill built his clothesline racer using a Lego Mindstorms microcontroller brick. servos, and sensors.

ON THE LINE Scott Hill built his clothesline racer using a Lego Mindstorms microcontroller brick. servos, and sensors.

RULES AND PRIZES

Under Hack Factory rules, each racer:

![]() Must be self-contained in terms of power and control. The exception is that the racer may be manually activated at the beginning of the run.

Must be self-contained in terms of power and control. The exception is that the racer may be manually activated at the beginning of the run.

![]() Must weigh less than 3lbs, fully fueled. This is based on the strength of the line. A very strong cable solidly anchored at either end might not need a weight limitation.

Must weigh less than 3lbs, fully fueled. This is based on the strength of the line. A very strong cable solidly anchored at either end might not need a weight limitation.

![]() Must not exceed 12"×12"×12". This prevents cheats like telescoping extenders that would enable the racer to reach the end plate faster than it ought.

Must not exceed 12"×12"×12". This prevents cheats like telescoping extenders that would enable the racer to reach the end plate faster than it ought.

![]() Must complete the circuit. Racers begin the race in contact with the initial stop, make contact with the far stop, then return to contact the first stop.

Must complete the circuit. Racers begin the race in contact with the initial stop, make contact with the far stop, then return to contact the first stop.

![]() Must be able to be placed quickly and easily on the wire.

Must be able to be placed quickly and easily on the wire.

![]() May not damage or adulterate the wire or stops. No residue, soot, char, rubber, goop, or anything else left behind, and no cutting or abrading.

May not damage or adulterate the wire or stops. No residue, soot, char, rubber, goop, or anything else left behind, and no cutting or abrading.

![]() Must finish the race with all parts (except fuel) intact and still within the cubic volume.

Must finish the race with all parts (except fuel) intact and still within the cubic volume.

![]() Must be safe for other racers and spectators alike. No racer may use liquid-fueled rockets; jet engines; high-pressure air, water, or steam mechanisms; or other elements deemed dangerous. Solid rocket motors must be store-bought, not larger than ¼A rating in size, and limited to two per racer.

Must be safe for other racers and spectators alike. No racer may use liquid-fueled rockets; jet engines; high-pressure air, water, or steam mechanisms; or other elements deemed dangerous. Solid rocket motors must be store-bought, not larger than ¼A rating in size, and limited to two per racer.

![]() SPEED RACER Hack Factory member Brandon Paplow inspects his racer. Adding a little whimsy to your racer can only help you win points.

SPEED RACER Hack Factory member Brandon Paplow inspects his racer. Adding a little whimsy to your racer can only help you win points.

Bob Poate (right)

Each racer gets up to three starts and must complete two runs, its best time being its score. Failure to complete the course after three attempts disqualifies the racer, and judges may rule that a racer is failing to make headway if it does not move for 30 seconds.

Prizes for the event are awarded for Speed, Creative Appearance, Creative Locomotion (method of propulsion), Loudest, Size (smallest and lightest), and Epic Failure. Note that the last of these must be judged an honest, unintentional failure.

John Baichtal is a contributor to MAKE and the GeekDad blog on wired.com.