Chapter 17 Study Questions

What is the communication process?

How can collaboration be improved by better communication?

How can we deal positively with conflict?

How can we negotiate successful agreements?

"My Siamese cat Skimbleshanks is up a tree... At Wilco concert—Jeff Tweedy is so cool Home alone ... Flying to Ireland, wish me luck driving ... Just saw Todd with Stephanie!"

So who cares? Well it turns out that a lot of people care, just as Evan Williams and Biz Stone co-founders of Twitter, had anticipated. They are the guys who moved microblogging into the upper limits. And the quick, easy, and ever-present social networking offered through Twitter isn't just for friends and family—companies are using it, radio and television shows are using it, and, of course, celebrities are using it.

According to David Murray, director of social Web communications at Bivings Group, "Twitter is a digital handshake. It's one of the fastest ways you can reach out to people." The Twitter concept of sending 140 character or less "tweets" hit the mark with traffic rising quickly to the 40 million range. "I guess we have a lot of things we think we can prove," Stone says, "to provide the infrastructure for a new kind of communication, and then support the creativity that emerges." For his part, Williams points out: "we're totally focused on making the best user experience possible and building a defensible communications network."

Both Stone and Williams have been part of the Internet business community through many past ventures, including Blogger, which was purchased by Google. Williams is actually credited with coining the word "blog," and Stone has published two books on blogging. From something that Stone calls "the side project that took," the Twitter revolution has had a broad impact. But it's also challenging for the firm and its founders. Twitter is dealing with rapid growth in both users and employees, lack of business expertise on the staff, and the need to turn the Twitter user experience into revenue generation. Williams says: "If it weren't growing nearly as fast, we would be building a lot more things."

Are you part of the Twitter community, on Facebook, always juggling multiple windows on your PC, married to your mobile device ... and more? Technology hasn't just changed how we communicate; it has created a social media revolution that even managers are finding can be a performance asset. There's no doubt that the ability to achieve positive personal impact through communication and collaboration is a "must-have" management competency.

Speaking about personal development, how strong are your communication and networking skills? Recruiters give them high priority when screening candidates for college internships and first jobs. Who wants to hire someone that can't communicate well both orally and in writing, and network well with others for collaboration and work accomplishment? Those are the facts, but, if you're like many of us, there's work to be done to master the challenge

Compare your communication skills with these data. The American Management Association reports that workers rated their bosses only slightly above average on transforming ideas into words, being credible, listening and asking questions, and giving written and oral presentations. Over three-quarters of university professors in one survey rated incoming high school graduates as only "fair" or "poor" in writing clearly, and in spelling and use of grammar.[974] And when it comes to decorum, or just plain old "good manners," a BusinessWeek survey reports that 38% of women complain about "sexual innuendo, wisecracks and taunts" at work.[975]

When it comes to networking skills, don't forget that we often do well or poorly at work as a result of how well we use communication to link with other people. Social networking is in on the college campus and among young professionals, as everyone wants to be "linked in." The same skills have to transfer to the workplace. For some of us, networking is as natural as walking down the street, but for others it can be a challenge. A good networker is able to act as a hub–connected with others gatekeeper— moving information to and from others; and pulse-taker— staying abreast of what is happening.[976]

Can you convince a recruiter that you are ready to run effective meetings, write informative reports, deliver persuasive presentations, conduct job interviews, use e-mail and social media well, keep conflicts constructive and negotiations positive, and network well with peers and mentors? The list is long, but every item on it counts. Make use of the end-of-chapter Self-Assessment feature to further reflect on your communication and networking skills, as well as your use of Conflict Management Strategies.

Visual Chapter Overview

17 Communication and Collaboration

Study Question 1 | Study Question 2 | Study Question 3 | Study Question 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

The Communication Process | Improving Collaboration | Managing Conflict | Managing Negotiation |

|

|

|

|

Learning Check 1 | Learning Check 2 | Learning Check 3 | Learning Check 4 |

When recruiters are asked what attributes are most important for graduates of business schools, interpersonal skills often top the lists.[977] Whether you work at the top—building support for strategies and organizational goals, or at lower levels—interacting with others to support their work efforts and your own, your career tool kit must include abilities to achieve positive impact through communication and collaboration. They are foundations for something all managers need— social capital, the capacity to attract support and help from others in order to get things done.

• Social capital is a capacity to get things done with the support and help of others.

Whereas intellectual capital is basically what you know, social capital comes from the people you know and how well you relate to them. Pam Alexander, former CEO of Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide, says: "Relationships are the most powerful form of media. Ideas will only get you so far these days. Count on personal relationships to carry you further."[978]

Think back to the descriptions of managerial work by Henry Mintzberg and John Kotter as discussed in Chapter 1. For Mintzberg, managerial success involves performing well as an information "nerve center," gathering information from and disseminating information to internal and external sources.[979] For Kotter, it depends largely on one's ability to build and maintain a complex web of interpersonal networks with insiders and outsiders so as to implement work priorities and agendas.[980] And when it comes to such capacities for communication and collaboration, most of us probably get it right some of the time but also make our fair share of mistakes. Here are three examples of managers who took steps toward self-improvement by participating in workshops held at the Center for Creative Leadership, or CCL.[981]

Richard Herlich went to the CCL after being promoted to director of marketing for his firm. "I thought I had the perfect style," he said. But role-playing exercises showed that others perceived him as aloof and a poor communicator. Richard made it a point in his new job to meet with his marketing team, discuss his style, and become more involved in their work projects.

Lisa DiTrullio learned from her CCL experiences that "feedback reassures and reenergizes you around what you're doing well and helps you identify areas for development." She gained confidence and says the CCL experience gave her "momentum and energy" to take her to the "next level" of accomplishment. She went on to found her own consulting firm—Lisa DiTrullio & Associates.

Vance Tang learned at CCL that he had an introverted personality, one that might cause others to see him as "cold and distant" in his role as CEO of Kone, Inc. Now he explains his style so people will understand that he isn't slighting them, and he also tries to be more "outgoing" in his relationships.

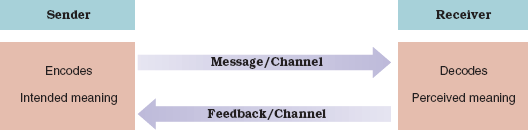

Although we can't all attend special training programs like those just described, we can learn from experience and strive to improve how we work with and relate to others. A solid first step is to understand our skills with communication, described in Figure 17.1 as an interpersonal process of sending and receiving symbols with messages attached to them. This process can be understood as a series of questions: "Who?" (sender) "says what?" (message) "in what ways?" (channel) "to whom?" (receiver) "with what result?" (interpreted meaning).

• Communication is the process of sending and receiving symbols with meanings attached.

The ability to communicate well both orally and in writing is a critical managerial skill and one of the foundation competencies for successful leadership. Through communication people exchange and share information with one another, and influence one another's attitudes, behaviors, and understandings. Managers, for example, use communication to establish and maintain interpersonal relationships, listen to others, deal with conflicts, negotiate, and otherwise gain the information needed to create a high-performance workplace.

One problem often encountered in communication is that we take our abilities for granted and end up being disappointed when the process breaks down. Another problem occurs when we are too busy, or too lazy, to invest enough time in making sure that the process really works. These problems raise questions of "effectiveness" and "efficiency" in the communication process. Effective communication occurs when the sender's message is fully understood by the receiver. Efficient communication occurs at minimum cost in terms of resources expended.

• In effective communication the intended meaning is fully understood by the receiver.

• Efficient communication occurs at minimum cost.

It's nice for our communications to be effective and efficient. But, as we all know, this isn't always achieved. For one thing, efficiency is sometimes traded for effectiveness. Picture your instructor taking the time to communicate individually with each student about this chapter. It would be virtually impossible. Even if it were possible, it would be costly. This is why managers often leave voice-mail messages and interact by e-mail, rather than visit people personally. These alternatives are more efficient than one-on-one and face-to-face communications, but they may not always be effective. Although an e-mail note to a distribution list may save time, not everyone might get the same meaning from the message.

By the same token, an effective communication may not always be efficient. If a team leader visits each team member individually to explain a new change in procedures, this may guarantee that everyone truly understands the change. But it may also take a lot of the leader's time. In these and other ways, potential trade-offs between effectiveness and efficiency must be recognized in communication.

Communication is not only about sharing information or being "heard." It often includes the intent of one party to influence or motivate the other in a desired way. Persuasive communication results in a recipient agreeing with or supporting the message being presented.[982] Managers get things done by working with and persuading others who are their peers, teammates, coworkers, and bosses. They often get things done more by convincing than by giving orders.

• Persuasive communication presents a message in a manner that causes the other person to support it.

Scholar and consultant Jay Conger says that many managers "confuse persuasion with taking bold stands and aggressive arguing."[983] He points out that this often leads to "counterpersuasion" responses and may even raise questions about credibility, something managers can't afford to lose. Credible communication earns trust, respect, and integrity in the eyes of others. And without credibility, Conger sees little chance that persuasion can be successful. Conger's advice is to build credibility for persuasive communication through expertise and relationships.

• Credible communication earns trust, respect, and integrity in the eyes of others.

To build credibility through expertise, you must be knowledgeable about the issue in question or have a successful track record in dealing with similar issues in the past. In a hiring situation where you are trying to persuade team members to select candidate A rather than B, for example, you must be able to defend your reasons. And it will always be better if your past recommendations turned out to be good ones. To build credibility through relationships, you must have a good working relationship with the person to be persuaded. And it is always easier to get someone to do what you want if that person likes you. In a hiring situation where you want to persuade your boss to provide a special bonus package to attract top job candidates, for example, having a good relationship with your boss can add credibility to your request.

When Yoshihiro Wada was president of Mazda Corporation, he once met with representatives of the firm's American joint venture partner, Ford. But he had to use an interpreter. He estimated that 20% of his intended meaning was lost in the exchange between himself and the interpreter, while another 20% was lost between the interpreter and the Americans.[984] When Stephen Martin was head of a firm in England, he once "went underground" for two weeks and posed under an assumed name as an office worker. He says: "They (workers) said things to me that they never have told their managers" ... "Our key messages were just not getting through to people" ... "We were asking the impossible of some of them." And when he shared these concerns with his firm's managers, they replied: "They never told us that!"[985]

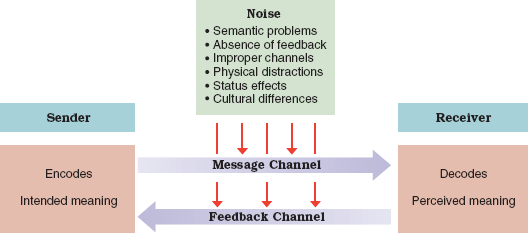

These examples show the downsides of noise, shown in Figure 17.2 as anything that interferes with the effectiveness of the communication process. The potential for noise is quite evident in foreign language situations like Wada's, but perhaps less evident in boss-worker communications like Martin's. And, do you recognize it in everyday conversations and even text messaging, as shown in the boxed exchange between a high-tech millennial and a low-tech baby boomer manager? Common sources of noise that often create communication barriers include information filtering, poor choice of channels, poor written or oral expression, failures to recognize nonverbal signals, and physical distractions.

• noise is anything that interferes with the effectiveness of communication.

Note

Millennial text to baby boomer

Omg sorry abt mtg nbd 4 now b rdy nxt time g2g ttl

Baby boomer text to millennial

Missed you at meeting. It was important. Don't forget next one. Stop by office.

"Criticize my boss? I don't have the right to." "I'd get fired." "It's her company not mine." The risk of ineffective communication may be highest when those at lower and higher levels in organizations are trying to communicate with each other. Consider the "corporate cover-up" once discovered at an electronics company. Product shipments were being predated and papers falsified as salespersons struggled to meet unrealistic sales targets set by the president. At least 20 persons in the organization cooperated in the deception, and it was months before the president found out. What happened in this case was information filtering–the intentional distortion of information to make it appear favorable to the recipient.

• Information filtering is the intentional distortion of information to make it appear most favorable to the recipient.

Tom Peters, management author and consultant, has called information distortion "Management Enemy Number 1." He even goes so far as to say that "once you become a boss you will never hear the unadulterated truth again."[986] The problem most often involves someone "telling the boss what he or she wants to hear."

Whether the reason behind this is a fear of retribution for bringing bad news, an unwillingness to identify personal mistakes, or just a general desire to please, the end result is the same. The higher-level person receiving filtered communications from below can end up making poor decisions because of a biased and inaccurate information base.

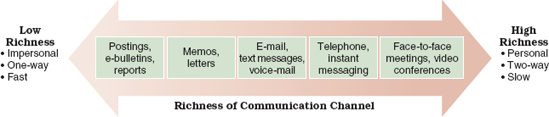

A communication channel is the pathway or medium through which a message is conveyed from sender to receiver. Good managers choose the right communication channel, or combination of channels, to accomplish their intended purpose.[987]

• A communication channel is the pathway through which a message moves from sender to receiver.

In general, written channels—paper or electronic memos, letters, and messages— are acceptable for simple messages that are easy to convey and for those that require extensive dissemination quickly. They are also important as documentation when formal policies or directives are being conveyed. Spoken channels such as meetings—virtual or face to face—work best for messages that are complex and difficult to convey and where immediate feedback to the sender is valuable. They are also more personal and can create a supportive, even inspirational, climate.

Communication will be effective only to the extent that the sender expresses a message in a way that can be clearly understood by the receiver. This means that words must be well chosen and properly used to express the sender's intentions. Consider the following "bafflegab" found among some executive communications.

A business report said: "Consumer elements are continuing to stress the fundamental necessity of a stabilization of the price structure at a lower level than exists at the present time." Translation: Consumers keep saying that prices must go down and stay down.

A manager said: "Substantial economies were affected in this division by increasing the time interval between distributions of data-eliciting forms to business entities." Translation: The division saved money by sending out fewer questionnaires.

A survey of 120 companies by the National Commission on Writing found that over one-third of their employees were considered deficient in writing skills and that employers were spending over $3 billion each year on remedial training.[988] Such training typically covers both written and oral expression. Management Smarts 17.1 offers guidelines on an important communication situation—the executive briefing or formal presentation.[989]

• Nonverbal communication takes place through gestures and body language.

Nonverbal communication takes place through such things as hand movements, facial expressions, body posture, eye contact, and the use of interpersonal space. It can be a powerful means of transmitting messages, with research showing that up to 55% of a message's impact may come through nonverbal communication.[990] In fact, a potential problem in the growing use of voice mail, text messaging, computer networking, and other electronic communications is that the loss of gestures and other nonverbal signals may lower communication effectiveness.

Think of how nonverbal signals play out in your own communications. The astute observer notes the "body language" expressed by other persons. Gestures, for example, can make a difference in whether someone's speech is positive or negative, excited or bored, or even engaged with or disengaged from you.[991] We can't forget that sometimes our body may be "talking" for us, even as we otherwise maintain silence. And when we do speak, our body may sometimes "say" different things than our words convey.

A mixed message occurs when a person's words communicate one message while his or her actions, body language, appearance, or use of interpersonal space communicate something else. Watch how people behave in a meeting. A person who feels under attack may move back in a chair or lean away from the presumed antagonist, even while expressing verbal agreement. All of this may be done quite unconsciously, but it sends a message that will be picked up by those who are on the alert.

• A mixed message results when words communicate one message while actions, body language, or appearance communicate something else.

Any number of physical distractions can interfere with communication effectiveness. Some of these distractions, such as telephone interruptions, drop-in visitors, and lack of privacy, are evident in the following conversation between an employee, George, and his manager.[992]

Okay, George, let's hear your problem [phone rings, boss picks it up, promises to deliver a report "just as soon as I can get it done"]. Uh, now, where were we—oh, you're having a problem with your technician. She's... [manager's assistant brings in some papers that need his immediate signature; assistant leaves] you say she's overstressed lately, wants to leave. I tell you what, George, why don't you [phone rings again, lunch partner drops by] uh, take a stab at handling it yourself. I've got to go now.

Besides what may have been poor intentions in the first place, the manager in this example did not do a good job of communicating with George. This problem could be easily corrected; many communication distractions can be avoided or at least minimized through proper planning. If George has something important to say, the manager should set aside adequate time for the meeting. Additional interruptions such as telephone calls and drop-in visitors could easily be eliminated by good planning.

After taking over as the CEO of the Dutch publisher Wolters Kluwer, Nancy McKinstry initiated major changes in strategy and operations—cutting staff, restructuring divisions, and investing in new business areas. As the first American to head the firm, she first described the new strategy as "aggressive" when speaking with her management team. But after learning the word wasn't well received by Europeans, she switched to "decisive." She says: "I was coming across as too harsh, too much of a results-driven American to the people I needed to get on board."[993]

When the sender and receiver are from different cultures, communicating is a significant challenge, one well recognized by international travelers and executives. To begin, it's hard to communicate when you don't speak each other's languages. Messages even get lost in translation, as classic advertising miscues such as these demonstrate. A Pepsi ad in Taiwan that intended to say "The Pepsi Generation" came out as "Pepsi will bring your ancestors back from the dead"; a KFC ad in China that intended to convey "finger lickin' good" came out as "eat your fingers off."[994] Cultural differences are also common in nonverbal communication, including everything from the use of gestures to interpersonal space.[995] The American "thumbs-up" sign is an insult in Ghana and Australia; signaling "OK" with thumb and forefinger circled together is not okay in parts of Europe; whereas we wave "hello" with an open palm, in West Africa it's an insult, suggesting the other person has five fathers.[996]

One of the major enemies of effective cross-cultural communication is ethnocentrism–the tendency to consider one's culture superior to any and all others. Ethnocentrism can hurt communication in at least three major ways. First, it may cause someone to not listen well to what others have to say. Second, it may cause someone to address or speak with others in ways that alienate them. And third, it may lead to the use of inappropriate stereotypes when dealing with persons from other cultures.[997]

• Ethnocentrism is the tendency to consider one's culture superior to any and all others.

Note

✓ Learning Check

Study Question 1

What is the communication process?

Be sure you can ✓ describe the communication process and identify its key components ✓ differentiate between effective and efficient communication ✓ explain the role of credibility in persuasive communication ✓ list the common sources of noise that inhibit effective communication ✓ explain how mixed messages and filtering interfere with communication ✓ explain how ethnocentrism affects cross-cultural communication

Effective communication is an essential foundation for collaboration as people work together in organizations. And the better the communication, the greater the likelihood of successful collaboration. A number of things can be done to improve the communication process by reducing noise, overcoming barriers, and improving interpersonal connections. They include transparency, interactive management, use of electronic media, active listening, constructive feedback, and space design.

At HCL Industries, a large technology outsourcing firm, CEO Vineet Nayar believes that one of his most important tasks for a CEO is to create a "culture of trust" in the firm. To do that, he says, you have to create transparency. At HCL, transparency means that the firm's financial information is fully posted on the internal Web. As Nayar puts it, "We put all the dirty linen on the table." Transparency also means that the results of 360° feedback reviews for HCL's 3,800 managers are posted on the internal Web, including Nayar's own reviews. And when managers present plans to the top management team, Nayar insists that they too get posted on the internal Web so that others can read and comment on them. By the time a plan is approved it's likely to be a good one, Nayar says, because of the "massive collaborative learning that took place."[998]

• Communication transparency involves openly sharing honest and complete information about the organization and workplace affairs.

As just illustrated, communication transparency involves being honest and openly sharing accurate and complete information about the organization and workplace affairs. A lack of communication transparency is evident when managers try to hide such information and restrict the access of organizational members to it. The expected result of being transparent and open in communication is a positive impact on employee engagement and greater feelings of trust between them and their managers.

Open communication was one of the hallmarks of how Nucor CEO Daniel R. DiMicco handled the impact of recession on his firm and its employees. Instead of hunkering down behind closed doors talking about the crisis with other executives, DiMicco doubled the time he spent out in the firm's plants talking with employees. He and his managers kept everyone informed about the status of orders for the firm's products. The open communication is well appreciated. One employee sent a card to top management saying, "Thank you for caring about me and my family"[999]

This emphasis on communication transparency is sometimes associated with the notion of open book management, in which managers like Vineet Nayar and Daniel DiMicco provide employees with essential financial information about their companies. At Bailard, Inc., a private investment firm, this openness extends to salaries; if you want to know what others are making at the firm, all you need to do is ask the chief financial officer. The firm's co-founder and CEO Thomas Bailard believes this is a good way to defeat office politics. "As a manager," he says, "if you know that your compensation decisions are essentially going to be public, you have to have pretty strong conviction about any decision you make."[1000]

• Open book management is where managers provide employees with essential financial information about their companies.

One of the ways to pursue transparency is by adopting interactive management practices that keep communication channels open between organizational levels. A popular choice is management by wandering around (MBWA)–dealing directly with subordinates or team members by regularly spending time walking around and talking with them. It is basically communicating face to face to find out what is going on. Another interactive management practice involves open office hours whereby busy executives set aside time in their calendars to welcome walk-in visits during certain hours. A rotating schedule of "shirtsleeve" meetings can also bring top managers into face-to-face contact with mixed employee groups throughout an organization. And some organizations form groups such as elected employee advisory councils whose members meet with management on a regular schedule to share information and discuss issues.

• In management by wandering around (MBWA), managers spend time outside their offices to meet and talk with workers at all levels.

Today, interactive management also takes many electronic forms creating what might be called virtual MBWA. Things like online discussion forums, always-on instant messaging, electronic office hours, executive blogs, and video conferences allow managers to overcome time and distance limitations that might otherwise make communication more difficult and less regular.

Today's array of electronic media has lots to offer in management, but its limits also need to be understood.[1001] Good, old-fashioned face-to-face communication hasn't gone away and can often be the better choice. Consider, for example, the issue of channel richness–the capacity of a communication channel to carry information in an effective manner.[1002] Figure 17.3 shows that face-to-face communication is very high in richness because it allows for two-way interaction and real-time feedback. Written reports, memos, and e-mail are lower in richness because they are more one-way and offer limited opportunity for feedback.

• Channel richness is the capacity of a communication channel to effectively carry information.

In everyday interactions and at work we are often advised to err on the side of "over communicating," staying in touch, sending information, and expressing gratitude even a bit more than necessary. And electronic media make this pretty easy. But they can be misused as well. Sending a message like "Thnx for the IView! I Wud Luv to Work 4 U!!;)" isn't the follow-up message most employers like to receive from job candidates. When Tory Johnson, president of Women for Hire, Inc., received a thank-you note by e-mail from an intern candidate, it included "hiya," "thanx," three exclamation points, and two emoticons. She says: "That e-mail just ruined it for me."[1003] Even though textspeak and emoticons are the norm in social networks, most staffing professionals consider their use "not professional."

Privacy is also a big issue in the electronic workplace.[1004] And when Facebook's CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, says privacy is "no longer a social norm," it's time to take the issue seriously. While employees are concerned that employers are eavesdropping on their computer usage, employers are concerned that too much work time gets spent in personal Web browsing and social networking. They're also concerned about the purpose driving some of that use. Consider this tweet that became an Internet sensation: "Cisco just offered me a job! Now I have to weigh the utility of a fatty paycheck against the daily commute to San Jose and hating the work"[1005] What would you do if you were the recruiter who had just made this job offer? When it comes to Web browsing and using electronic media at work, the best advice comes down to this: Find out the employer's policy and follow it. And don't ever assume that you have electronic privacy; chances are the employer is checking or can easily check on you.[1006]

• Electronic grapevines use electronic media to pass messages and information among members of social networks.

The electronic grapevine is now a fact of life as electronic messages fly around our world with great speed as they carry both accurate and inaccurate information. Not too long ago, for example, a law professor told his class that Chief Justice John Roberts was resigning from the U.S. Supreme Court—it was a lesson on checking facts of stories. By the time students realized what he was doing, the false story had been spread by instant messaging and e-mails to the point of almost making the national news.[1007]

This power of the electronic grapevine has its upside and downside. On the upside, General Electric started a "Tweet Squad" to advise the rest of the organization how social networking could be used to improve internal collaboration.[1008] Domino's Pizza executives felt the downside when a YouTube video showed two Domino's employees doing all sorts of nasty things to sandwiches. It was soon viewed over a million times and by the time the video was pulled (by one of its authors who apologized for "faking"), negative chat created a crisis in customer confidence. Domino's management finally created a Twitter account and posted a YouTube video message from the CEO to present its own view of the story.[1009]

Whether trying to communicate electronically or face to face, managers must be very good at listening. When people "talk," they are trying to communicate something. That "something" may or may not be what they are saying.

Active listening is the process of taking action to help someone say exactly what he or she really means.[1010] It involves being sincere and trying to find out the full meaning of what is being said. It also involves being disciplined in controlling emotions and withholding premature evaluations or interpretations. Different responses to the following two questions contrast how a "passive" listener and an "active" listener might act in real workplace conversations.

• Active listening helps the source of a message say what he or she really means.

Question 1: "Don't you think employees should be promoted on the basis of seniority?" Passive listener's response: "No, I don't!" Active listener's response: "It seems to you that they should, I take it?"

Question 2: "What does the supervisor expect us to do about these out-of-date computers?" Passive listener's response: "Do the best you can, I guess." Active listener's response: "You're pretty frustrated with those machines, aren't you?"

These examples help show how active listening can facilitate rather than discourage communication in difficult circumstances. As you think further about what you can do to get better at active listening, keep these rules in mind.[1011]

Listen for message content: Try to hear exactly what content is being conveyed in the message.

Listen for feelings: Try to identify how the source feels about the content in the message.

Respond to feelings: Let the source know that her or his feelings are being recognized.

Note all cues: Be sensitive to nonverbal and verbal messages; be alert for mixed messages.

Paraphrase and restate: State back to the source what you think you are hearing.

The process of telling other people how you feel about something they did or said, or about the situation in general, is called feedback. Consider these examples of the types of feedback people receive and deliver to one another.[1012]

• Feedback is the process of telling someone else how you feel about something that person did or said.

Evaluative feedback: "You are unreliable and always late for everything."

Interpretive feedback: "You're coming late to meetings; you might be spreading yourself too thin and have trouble meeting your obligations."

Descriptive feedback: "You were 30 minutes late for today's meeting and missed a lot of the context for our discussion."

The art of giving feedback is an indispensable skill, particularly for managers who must regularly give feedback to other people. When poorly done, feedback can be threatening to the recipient and cause resentment. When properly done, feedback—even performance criticism—can be listened to, accepted, and used to good advantage by the receiver.[1013] When Lydia Whitefield, a marketing vice president at Avaya, asked one of her managers for feedback, she was surprised. He said: "You're angry a lot." Whitfield learned from the experience, saying: "What he and other employees saw as my anger, I saw as my passion."[1014]

There are ways to make sure that feedback is useful and constructive rather than harmful. To begin, the feedback should offer real benefit to the receiver and not just satisfy some personal need of the sender. A supervisor who berates a computer programmer for errors, for example, may actually be angry about failing to give clear instructions in the first place. The sender should also follow those guidelines to make sure that feedback is always understandable, acceptable, plausible, and "constructive."[1015]

Give feedback directly and with real feeling, based on trust between you and the receiver.

Make sure that feedback is specific rather than general; use good, clear, and preferably recent examples to make your points.

Give feedback at a time when the receiver seems most willing or able to accept it.

Make sure the feedback is valid; limit it to things the receiver can be expected to do something about.

Give feedback in small doses; never give more than the receiver can handle at any particular time.

Other important lessons about communication can be found in proxemics, the study of how we use space.[1016] Simply put, space and how we use it is a form of communication. The distance between people conveys varying intentions in terms of intimacy, openness, and status in interpersonal communications. And the physical layout of an office or room is a form of nonverbal communication. Think about it.

Offices with chairs available for side-by-side seating convey different messages than offices where the manager's chair sits behind the desk and those for visitors sit facing it in front. An extreme example of space design and communication confronted Tim Armstrong when he became CEO of AOL. One of his first decisions was to remove the doors separating executive offices from other workers. Previously the only way to open them had been with a company key card.[1017]

Architects and consultants specializing in organizational ecology are helping executives build offices conducive to the intense communication needed in today's work environments. When Sun Microsystems built its San Jose, California, facility public spaces were designed to encourage communication among persons from different departments. Many meeting areas had no walls, and most walls were glass. As manager of planning and research, Ann Bamesberger said: "We were creating a way to get these people to communicate with each other more."[1018] At Google headquarters, or "googleplex," telecommuters work in specially designed office "tents." These are made of acrylics to allow both a sense of private, personal space and transparency.[1019] And at b&a advertising in Dublin, Ohio, "open space" supports the small ad agency's emphasis on creativity—after all, its Web address is www.babrain.com. There are no offices or cubicles, and all office equipment is portable. Desks have wheels so that informal meetings can take place by people repositioning themselves for spontaneous collaboration. Even the formal meetings are held "standing up" in the company kitchen. Face-to-face communication is the rule; internal e-mail among b&a employees is banned.[1020]

Note

✓ Learning Check

Study Question 2

How can we improve our communications?

Be sure you can ✓ explain how transparency and openness improves communication ✓ explain how interactive management and practices like MBWA can improve upward communication ✓ discuss possible uses of electronic media by managers ✓ define active listening and list active listening rules ✓ illustrate the guidelines for constructive feedback ✓ explain how space design influences communication

Among your communication and collaboration skills, the ability to deal with conflicts is critical. Conflict is a disagreement between people on substantive or emotional issues.[1021] Managers and team leaders spend a lot of time dealing with conflicts of both types. Substantive conflicts involve disagreements over such things as goals and tasks, allocation of resources, distribution of rewards, policies and procedures, and job assignments. Emotional conflicts result from feelings of anger, distrust, dislike, fear, and resentment, as well as from personality clashes and relationship problems. Both forms of conflict can cause difficulties. But when managed well, they can also be helpful in promoting creativity and high performance.

• Conflict is a disagreement over issues of substance and/or an emotional antagonism.

• Substantive conflict involves disagreements over goals, resources, rewards, policies, procedures, and job assignments.

• Emotional conflict results from feelings of anger, distrust, dislike, fear, and resentment, as well as from personality clashes.

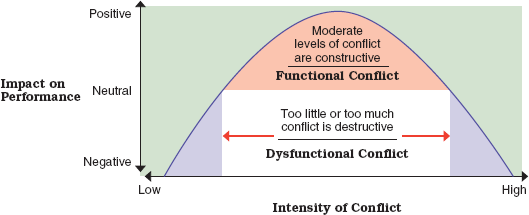

The inverted "U" curve depicted in Figure 17.4 shows that conflict of moderate intensity can be good for performance. This functional conflict, or constructive conflict, stimulates people toward greater work efforts, cooperation, and creativity. It helps teams achieve their goals and avoid groupthink, described in the last chapter as a tendency for highly cohesive groups to make bad decisions because members are unwilling to engage in conflict.

• Functional conflict is constructive and helps task performance.

At very low or very high intensities, dysfunctional conflict, or destructive conflict, occurs. Too much conflict is distracting and interferes with other more task-relevant activities. Too little conflict promotes groupthink, complacency, and the loss of a high-performance edge.

• Dysfunctional conflict is destructive and hurts task performance.

When it comes to managing conflict, it helps to understand the antecedent conditions that make the emergence of conflict more likely. Role ambiguities set the stage for conflict. Unclear job expectations and other task uncertainties increase the probability that some people will be working at cross-purposes, at least some of the time. Resource scarcities cause conflict. Having to share resources with others or compete directly with them for resource allocations creates a potential conflict situation, especially when resources are scarce. Task interdependencies cause conflict. When individuals or groups must depend on what others do to perform well themselves, conflicts often occur.

Competing objectives are also opportunities for conflict. When goals are poorly set or reward systems are poorly designed, individuals and groups may come into conflict by working to one another's disadvantage. Structural differentiation breeds conflict. Differences in organization structures and in the characteristics of the people staffing them may foster conflict because of incompatible approaches toward work. And unresolved prior conflicts tend to erupt in later conflicts. Unless a conflict is fully resolved, it may remain latent only to emerge again in the future.

When conflicts do occur, they can either be "resolved," in the sense that the causes are corrected, or "suppressed," in that the causes remain but the conflict behaviors are controlled. Suppressed conflicts tend to fester and recur at a later time. True conflict resolution eliminates the underlying causes of conflict and reduces the potential for similar conflicts in the future.

• Conflict resolution is the removal of the substantial and emotional reasons for a conflict.

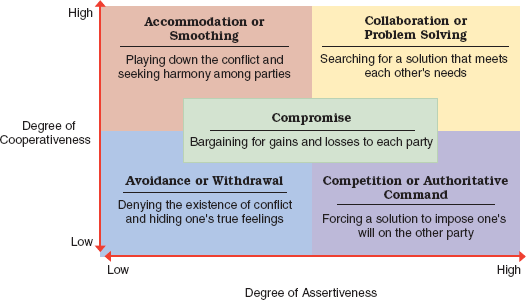

People respond to interpersonal conflict through different combinations of cooperative and assertive behaviors.[1022] Cooperativeness is the desire to satisfy another party's needs and concerns; assertiveness is the desire to satisfy one's own needs and concerns. Figure 17.5 shows five interpersonal styles of conflict management that result from various combinations of these two tendencies.[1023]

Avoidance or withdrawal–being uncooperative and unassertive, downplaying disagreement, withdrawing from the situation, and/or staying neutral at all costs.

Accommodation or smoothing–being cooperative but unassertive, letting the wishes of others rule, smoothing over or overlooking differences to maintain harmony.

Competition or authoritative command–being uncooperative but assertive, working against the wishes of the other party, engaging in win-lose competition, and/or forcing through the exercise of authority.

Compromise–being moderately cooperative and assertive, bargaining for "acceptable" solutions in which each party wins a bit and loses a bit.

Collaboration or problem solving–being cooperative and assertive, trying to fully satisfy everyone's concerns by working through differences, finding and solving problems so that everyone gains.[1024]

• Avoidance, or withdrawal, pretends that a conflict doesn't really exist.

• Accommodation, or smoothing, plays down differences and highlights similarities to reduce conflict.

• Competition, or authoritative command, uses force, superior skill, or domination to "win" a conflict.

• Compromise occurs when each party to the conflict gives up something of value to the other.

• Collaboration, or problem solving, involves working through conflict differences and solving problems so everyone wins.

Avoiding or accommodating often creates lose-lose conflict. No one achieves her or his true desires, and the underlying reasons for conflict remain unaffected. Although the conflict appears settled or may even disappear for a while, it tends to recur in the future. Avoidance is an extreme form of nonattention. Everyone withdraws and pretends that conflict doesn't really exist, hoping that it will simply go away. Accommodation plays down differences and highlights similarities and areas of agreement. Peaceful coexistence is the goal, but the real essence of a conflict may be ignored.

• In lose-lose conflict no one achieves his or her true desires, and the underlying reasons for conflict remain unaffected.

• In win-lose conflict one party achieves its desires, and the other party does not.

Competing and compromising tend to create win-lose conflict where each party strives to gain at the other's expense. In extreme cases, one party achieves its desires to the complete exclusion of the other party's desires. Because win-lose methods fail to address the root causes of conflict, future conflicts of the same or a similar nature are likely to occur. In competition, one party wins because superior skill or outright domination allows his or her desires to be forced on the other. An example is authoritative command where a supervisor simply dictates a solution to subordinates. Compromise occurs when trade-offs are made such that each party to the conflict gives up and gains something. But because each party loses something, antecedents for future conflicts are established.

Collaborating or true problem solving is a form of win-win conflict. It is often the most effective conflict management style because issues are resolved to the mutual benefit of all conflicting parties. This is typically achieved by confronting the issues and by everyone being willing to recognize that something is wrong and needs attention. Win-win outcomes eliminate the underlying causes of the conflict; all relevant issues are raised and discussed openly.

• In win-win conflict the conflict is resolved to everyone's benefit.

Most managers will tell you that not all conflict management in groups and organizations can be resolved at the interpersonal level. Think about it. Aren't there likely to be times when personalities and emotions prove irreconcilable? In such cases a structural approach to conflict management can often help.

When conflict traces back to a resource issue, the structural solution is to make more resources available to everyone. Although costly and not always possible, this is a straightforward way to resolve resource-driven conflicts. When people are stuck in conflict and just can't seem to appreciate one another's points of view, appealing to higher-level goals can sometimes focus their attention on one mutually desirable outcome. In a student team where members are arguing over content choices for a PowerPoint presentation, for example, it might help to remind everyone that the goal is to impress the instructor and get an "A" for the presentation. An appeal to higher goals offers a common frame of reference for analyzing differences and reconciling disagreements.

When appeals to higher goals don't work, it may be that changing the people is necessary. There are times when a manager may need to replace or transfer one or more of the conflicting parties to eliminate the conflict. When the people can't be changed, they may have to be separated by altering the physical environment. Sometimes it is possible to rearrange facilities, work space, or workflows to physically separate conflicting parties and decrease opportunities for contact with one another. Organizations also use a variety of integrating devices to help manage conflicts between groups. These approaches include assigning people to formal liaison roles, convening special task forces, setting up cross-functional teams, and even switching to the matrix form of organization.

Providing training in interpersonal skills can also help prepare people to communicate and work more effectively in situations where conflict is likely. When corporate recruiters list criteria for recruiting new college graduates, such "soft" or "people" skills are often right at the top. In today's horizontal and team-oriented organizations, you can't succeed if you can't work well with other people even when disagreements are inevitable. Finally, by changing reward systems it is sometimes possible to reduce conflicts that arise when people feel they have to compete with one another for attention, pay, and other rewards. An example is shifting pay bonuses or even student project grades to the group level so that individuals benefit in direct proportion to how well the team performs as a whole. This is a way of reinforcing teamwork and reducing the tendencies of team members to compete with one another.

Note

Structural ways to manage conflict

Make resources available

Appeal to higher goals

Change the people

Change the environment

Use integrating devices

Provide training

Change reward systems

Note

✓ Learning Check

Study Question 3

How can we deal positively with conflict?

Be sure you can ✓ differentiate substantive and emotional conflict ✓ differentiate functional and dysfunctional conflict ✓ explain the common causes of conflict ✓ define conflict resolution ✓ explain the conflict management styles of avoidance, accommodation, competition, compromise, and collaboration ✓ discuss lose-lose, win-lose, and win-win conflicts ✓ list the structural approaches to conflict management

Situation: Your employer offers you a promotion, but the pay raise being offered is disappointing.

Situation: You have enough money to order one new computer for your department, but two of your subordinates really need one.

Situation: Your team members are having a "cook-out" on Saturday afternoon and want you to attend; your husband wants you to go with him to a neighboring town to visit his mother in the hospital.

Situation: Someone on your sales team has to fly to Texas to visit an important client; you've made the last two trips out of town and don't want to go; another member of the team hasn't been out of town in a long time and "owes" you a favor.

These are examples of the many work situations that lead to negotiation–the ocess of making joint decisions when the parties involved have different preferences. Stated a bit differently negotiation is a way of reaching agreement. People negotiate over performance evaluations, job assignments, work schedules, work locations, and many other things. And, as pointed out in Management Smarts 17.2, they negotiate over salaries.[1025] Any and all such negotiations are susceptible to conflict and negative aftermath, and test the communication and collaboration skills of those involved.[1026]

• Negotiation is the process of making joint decisions when the parties involved have different preferences.

• Substance goals in negotiation are concerned with outcomes.

• Relationship goals in negotiation are concerned with the ways people work together.

• Effective negotiation resolves issues of substance while maintaining a positive process.

Two important goals should be considered in any negotiation. Substance goals in negotiation are concerned with outcomes and are tied to content issues. Relationship goals in negotiation are concerned with processes. They are tied to the way people work together while negotiating and how they (and any constituencies they represent) will be able to work together again in the future.

Effective negotiation occurs when issues of substance are resolved and working relationships among the negotiating parties are maintained, or even improved, in the process. The three criteria of effective negotiation are:

quality–negotiating a "wise" agreement that is truly satisfactory to all sides;

cost–negotiating efficiently, using a minimum of resources and time; and

harmony–negotiating in a way that fosters, rather than inhibits, interpersonal relationships.[1027]

The way each party approaches a negotiation can have a major impact on its effectiveness.[1028] Distributive negotiation focuses on "claims" made by each party for certain preferred outcomes. This emphasis on substance can take a self-centered and competitive form in which one party can gain only if the other loses. In such win-lose conditions, relationships are often sacrificed as the negotiating parties focus only on their respective self-interests.

• Distributive negotiation focuses on win-lose claims made by each party for certain preferred outcomes.

Principled negotiation, often called integrative negotiation, is based on a win-win orientation. The focus on substance is still important, but the interests of all parties are considered. The goal is to base the final outcome on the merits of individual claims and to try to find a way for all claims to be satisfied, if at all possible. No one should lose in a principled negotiation, and positive relationships should be maintained in the process.

• Principled negotiation or integrative negotiation uses a "win-win" orientation to reach solutions acceptable to each party.

When asked by an interviewer to illustrate how the integrative approach to negotiation differs from a distributive one, scholor and consultant William Ury gave this example.[1029] A union worker presents a manager with a list of requests. The manager says: "That's your solution, now what's the problem?" The union worker responds with a list of problems. The manager says: "Well, I can't give you that solution, but I think we can solve your problem this way."

Can you see the manager's attempt to be "integrative" in the last example?[1030] In their book Getting to Yes, Roger Fisher and William Ury point out that truly integrative agreements are obtained by following four negotiation rules.[1031]

Separate the people from the problem.

Focus on interests, not on positions.

Generate many alternatives before deciding what to do.

Insist that results be based on some objective standard.

Proper attitudes and good information are necessary foundations for integrative agreements. The attitudinal foundations involve the willingness of each negotiating party to trust, share information with, and ask reasonable questions of the other party. The information foundations involve both parties knowing what is really important to them and also finding out what is really important to the other party.

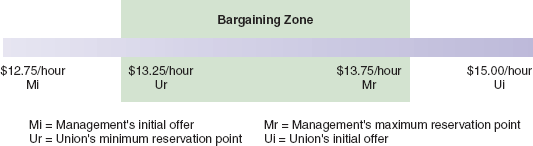

Both attitudes and information will come into play during a classic two-party labor-management negotiation over a new contract and salary increase.[1032] Look at Figure 17.6 and consider the situation from the labor union's perspective. The union negotiator has told her management counterpart that the union wants a new wage of $15.00 per hour. This expressed preference is the union's initial offer.

However, she also has in mind a minimum reservation point of $13.25 per hour. This is the lowest that she is willing to accept for the union. Now look at it from the perspective of the management negotiator. His initial offer is $12.75 per hour. And his maximum reservation point, the highest wage he is prepared to eventually offer the union, is $13.75 per hour.

• A bargaining zone is the space between one party's minimum reservation point and the other party's maximum reservation point.

In such a two-party negotiation, the bargaining zone is defined as the space between one party's minimum reservation point and the other party's maximum reservation point. The bargaining zone in this case lies between $13.25 per hour and $13.75 per hour. It is a "positive" zone since the reservation points of the two parties overlap. If the union's minimum reservation point was greater than management's maximum reservation point, no room would exist for bargaining. A key task for any negotiator is to discover the other party's reservation point. Until this is known and each party realizes that a positive bargaining zone exists, it is difficult to negotiate effectively.

The negotiation process is admittedly complex, and negotiators must guard against common pitfalls. The first is falling prey to the myth of the "fixed pie." This involves acting on the distributive and win-lose assumption that in order for you to gain in the negotiation, the other person must give something up. This approach to negotiating fails to recognize the integrative assumption that the "pie" can sometimes be expanded or utilized to everyone's advantage. A second negotiation error is non-rational escalation of conflict. The negotiator in this case becomes committed to previously stated "demands" and allows personal needs for "ego" and "saving face" to increase the perceived importance of satisfying them.

A third negotiating error is overconfidence and ignoring the other's needs. The negotiator becomes overconfident, believes his or her position is the only correct one, and fails to consider the needs of the other party or appreciate the merits of its position. The fourth error is too much "telling" and too little "hearing." The "telling" error occurs when parties to a negotiation don't really make themselves understood to each other. The "hearing" error occurs when they fail to listen well enough to understand what each other is saying.[1033]

Another potential negotiation pitfall, and one that is increasingly important in our age of globalization, is premature cultural comfort. This occurs when a negotiator is too quick to assume that he or she understands the intentions, positions, and meanings being communicated by a negotiator from a different culture. Scholar Jeanne Brett says, for example, that negotiators from low-context cultures can run into difficulties when dealing with negotiators from high-context cultures. The low-context negotiator is used to getting information through direct questions and answers; the high-context negotiator is likely to communicate indirectly, using nondeclarative language and nonverbal signals, and avoiding explicitly stated positions.[1034]

It is also important to avoid the trap of ethical misconduct. The motivation to negotiate unethically sometimes arises from an undue emphasis on the profit motive. This may be experienced as a desire to "get just a bit more" or to "get as much as you can" from a negotiation. The motivation to behave unethically may also result from a sense of competition. This is a desire to "win" a negotiation just for the sake of winning it, or because of the misguided belief that someone else must "lose" in order for you to gain. And let's not forget, ethical misconduct can be driven by all-consuming greed and the quest for profits in negotiation situations where financial considerations are at issue.

Note

Beware of negotiation pitfalls

Myth of fixed pie

Escalation of conflict

Overconfidence

Too much telling

Too little listening

Cultural miscues

Unethical behavior

When unethical behavior occurs in negotiation, the persons involved may try to explain it away with inappropriate rationalizing: "It was really unavoidable." "Oh, it's harmless." "The results justify the means." "It's really quite fair and appropriate."[1035] Of course these excuses for questionable behavior are morally unacceptable. They can also be challenged by the possibility that any short-run gains will be offset by long-run losses. Unethical negotiators will incur lasting legacies of distrust, disrespect, and dislike, and they can be targeted for "revenge" in later negotiations.

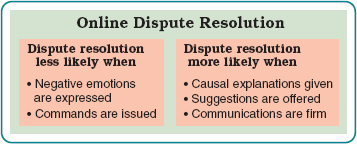

Even with the best of intentions, it may not always be possible to achieve integrative agreements. When disputes reach the point of impasse, third-party assistance with dispute resolution can be useful. Mediation involves a neutral third party who tries to improve communication between negotiating parties and keep them focused on relevant issues. The mediator does not issue a ruling or make a decision, but can take an active role in discussions. This may include making suggestions in an attempt to move the parties toward agreement.

• In mediation a neutral party tries to help conflicting parties improve communication to resolve their dispute.

Arbitration, such as salary arbitration in professional sports, is a stronger form of dispute resolution. It involves a neutral third party, the arbitrator, who acts as a "judge" and issues a binding decision. This usually includes a formal hearing in which the arbitrator listens to both sides and reviews all facets of the case before making a ruling.

• In arbitration a neutral third party issues a binding decision to resolve a dispute.

Some organizations formally provide for a process called alternative dispute resolution. This approach utilizes mediation or arbitration, but does so only after direct attempts to negotiate agreements between the conflicting parties have failed. Often an ombudsperson, a designated neutral third party who listens to complaints and disputes, plays a key role in the process.

Note

✓ Learning Check

Study Question 4

How can we negotiate successful agreements?

Be sure you can ✓ differentiate between distributive and principled negotiation ✓ list four rules of principled negotiation ✓ define bargaining zone and use this term to illustrate a labor-management wage negotiation ✓ describe the potential pitfalls in negotiation ✓ differentiate between mediation and arbitration