Chapter 3 Study Questions

What is ethical behavior?

How do ethical dilemmas complicate the workplace?

How can high ethical standards be maintained?

What is social responsibility and corporate governance?

"Business is the most powerful force in the world," says Gary Hirshberg. "I believe that virtually every problem in the world exists because business hasn't made finding a solution a priority."

Gary Hirshberg is the co-founder, president, and CEO of Stonyfield Farm, the world's largest producer of organic yogurt. He is also the author of Stirring It Up: How to Make Money and Save the World and was named one of "America's Most Promising Social Entrepreneurs" by BusinessWeek magazine. Hirshberg has always been at the forefront of movements for environmental and social transformation. He studied climate change at Hampshire College, built energy-producing windmills, and worked at a nonprofit research center that published studies on organic farming, aquaculture, and renewable energy sources.

The mission of Stoneyfield Farm is straightforward: "Offer a pure and healthy product that tastes good and earn a profit without harming the environment." Hirshberg says "We factor the planet into all our decisions."

Stonyfield Farm is committed to managing the triple bottom line of being economically, socially, and environmentally responsible. The company only uses dairy-farm suppliers who pledge not to use bovine growth hormone (BGH), installed solar panels on the factory roof, and built a water treatment plant. Under Hirshberg's leadership, it has recycled over 18 million pounds of material in the past 10 years and offset 100 percent of the greenhouse gases from its facility energy use. Hirshberg is also involved in programs to install healthy snack-food vending machines in schools.

"It's a simple strategy but a powerful one," says Hirshberg proudly. "Going green is not just the right thing to do, but a great way to build a successful business." Stonyfield Farm is now the number one maker of organic yogurt in the world.[118]

It is easy to appreciate Stonyfield's focus on the triple bottom line of profits, people, and planet. But can something like this only be done as a straight start-up, as in Hirshberg's case? Or, can an existing firm be refocused in this direction? What does it take to manage people and organizations in ways that create a work culture of ethics and social responsibility?

There is no doubt that Individual character is a foundation for all that we do. It establishes our personal integrity and provides an ethical anchor for how we behave at work and in life overall. Persons of high character are confident in the self-respect it provides, even in difficult situations. Those who lack it have lots of insecurity, act inconsistently, and suffer not only in self-esteem but also in the esteem of others.

You can think of individual character in terms of demonstrated honesty, civility, caring, and sense of fair play. And, indeed, the ethics and social responsibility issues facing organizations today put individual character to the test. We need to know ourselves well enough to make principled decisions that we can be proud of and that others will respect. After all, it's the character of the people making key decisions that determines whether our organizations act in socially responsible or irresponsible ways.

Research suggests that the behavior of some individuals changes greatly when they enter into the business arena. That is, the demands that the business world makes on individuals to be successful may cause them to act less ethically than otherwise. For instance, there is evidence that generosity, temperance, and sociability are reduced when one is operating in the business arena.[119]

One trait that can undermine individual character is hypercompetitiveness. Individuals who are hypercompetitive tend to think that winning—or getting ahead—is the only thing that matters. They hate to lose and tend to judge themselves more on the outcomes they achieve than on the methods used to get there. And, they may be quicker to put aside virtues in competitive situations like the business world.[120]

Although competitiveness is highly valued in many business situations, individuals who are too competitive may ignore ethical boundaries in their attempts to come out on top. They may even take actions that are unfair, damage society, or perhaps are even illegal.

Check yourself on the facets of hypercompetitiveness.[121] Identify three situations that presented you with some ethical test. Put yourself in the position of being your parent, a loved one, or a good friend. Using their vantage points, write a letter to yourself that critiques your handling of each incident and summarizes the implications in terms of your individual character. Also take advantage of the end-of-chapter Self-Assessment to further reflect on your terminal and instrumental values.

Visual Chapter Overview

3 Ethics and Social Responsibility

Study Question 1 | Study Question 2 | Study Question 3 | Study Question 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

What Is Ethical Behavior? | Ethics in the Workplace | Maintaining High Ethical Standards | Social Responsibility and Corporate Governance |

|

|

|

|

Learning Check 1 | Learning Check 2 | Learning Check 3 | Learning Check 4 |

The opening example of Stonyfield Farm should get you thinking about ethics, social responsibility, and principled leadership. Look around; there are many cases of people and organizations operating in admirable ways. Some are quite well known—Ben and Jerry's, Burt's Bees, Tom's of Maine, and Whole Foods Markets, for example. Surely there are others right in your local community. But as you think of the organizations, don't forget the people that run them—the ones whose behavior ultimately influences their organizations' performance. Consider also this reminder from Desmond Tutu, archbishop of Capetown, South Africa, and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

You are powerful people. You can make this world a better place where business decisions and methods take account of right and wrong as well as profitability.... You must take a stand on important issues: the environment and ecology, affirmative action, sexual harassment, racism and sexism, the arms race, poverty, the obligations of the affluent West to its less-well-off sisters and brothers elsewhere.[122]

For our purposes, ethics is defined as the moral code of principles that sets standards of good or bad, or right or wrong, in one's conduct.[123] A person's moral code is influenced by a variety of sources including family, friends, local culture, religion, educational institutions, and individual experiences.[124] Ethics guide and help people make moral choices among alternative courses of action. And in practice, ethical behavior is that which is accepted as "good" and "right" as opposed to "bad" or "wrong" in the context of the governing moral code.

• Ethics establish standards of good or bad, or right or wrong, in one's conduct.

• Ethical behavior is "right" or "good" in the context of a governing moral code.

Individuals often assume that anything that is legal should be considered ethical. Slavery was once legal in the United States, and laws once permitted only men to vote.[125] But that doesn't mean the practices were ethical. Sometimes legislation lags behind changes in moral positions within a society. The delay makes it possible for something to be legal during a time when most people think it should be illegal.[126]

By the same token, just because an action is not strictly illegal doesn't make it ethical.[127] Living up to the "letter of the law" is not sufficient to guarantee that one's actions will or should be considered ethical. Is it truly ethical, for example, for an employee to take longer than necessary to do a job? To call in sick so that you can take a day off work for leisure? To fail to report rule violations by a coworker? Although none of these acts is strictly illegal, many would consider them to be unethical.

Most ethical problems in the workplace arise when people are asked to do, or find they are about to do, something that violates their personal beliefs. For some, if the act is legal, they proceed without worrying about it. For others, the ethical test goes beyond legality and into personal values —the underlying beliefs and attitudes that help determine individual behavior.

• Values are broad beliefs about what is appropriate behavior.

The psychologist Milton Rokeach makes a distinction between "terminal" and "instrumental" values.[128] Terminal values are preferences about desired ends, such as the goals one strives to achieve in life. Examples of terminal values considered important by managers include self-respect, family security, freedom, and happiness. Instrumental values are preferences regarding the means for accomplishing these ends. Among the instrumental values held important by managers are honesty, ambition, imagination, and self-discipline.

• Terminal values are preferences about desired end states.

• Instrumental values are preferences regarding the means to desired ends.

The value pattern for any one person is very enduring, but values vary from one person to the next. And to the extent that they do, we can expect different interpretations of what behavior is ethical or unethical in a given situation. When commenting on cheating tendencies, an ethics professor at Insead in France once told business school students: "The academic values of integrity and honesty in your work can seem to be less relevant than the instrumental goal of getting a good job."[129] And when at Duke about 10% of an MBA class was caught cheating on a take-home final exam, some said that we should expect such behavior from students who are taught to collaborate and work in teams and utilize the latest communication technologies. For others, the instrumental values driving such behavior are unacceptable—it was an individual exam, the students cheated, and they should be penalized.[130]

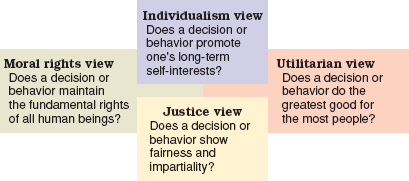

Figure 3.1 shows four views of ethical behavior—the utilitarian, individualism, moral rights, and justice views.[131] Depending on which perspective one adopts in a given situation, the resulting behaviors may be considered ethical or unethical.

The utilitarian view considers ethical behavior to be that which delivers the greatest good to the greatest number of people. Based on the work of 19th-century philosopher John Stuart Mill, this results-oriented point of view assesses the moral implications of actions in terms of their consequences. Business decision makers, for example, are inclined to use profits, efficiency, and other performance criteria to judge what is best for the most people. In a recession or when a firm is suffering through hard times, an executive may make a decision to cut 30% of the workforce in order to keep the company profitable and save the remaining jobs. She could justify this decision based on a utilitarian sense of business ethics.

• In the utilitarian view ethical behavior delivers the greatest good to the most people.

• In the individualism view ethical behavior advances longterm self-interests.

The individualism view of ethical behavior is based on the belief that one's primary commitment is to the long-term advancement of self-interests. The basic idea of this approach is that society will be best off if everyone acts in a way that maximizes his or her own utility or happiness. According to this viewpoint, people supposedly become self-regulating as they pursue long-term individual advantage. For example, lying and cheating for short-term gain should not be tolerated because if everyone behaves this way then no one's long-term interests will be served. The individualism view is supposed to promote honesty and integrity. But in business practice it may result in greed, a pecuniary ethic, described by one executive as the tendency to "push the law to its outer limits" and "run roughshod over other individuals to achieve one's objectives."[132]

Ethical behavior under a moral rights view is that which respects and protects the fundamental rights of people. From the teachings of John Locke and Thomas Jefferson, for example, the rights of all people to life, liberty, and fair treatment under the law are considered inviolate. In organizations, the moral rights concept extends to ensuring that employees are protected in rights to privacy, due process, free speech, free consent, health and safety, and freedom of conscience. The issue of human rights, a major ethical concern in the international business environment, is central to this perspective. The United Nations, as indicated in the accompanying box, stands by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights passed by the General Assembly in 1948.[133]

• In the moral rights view ethical behavior respects and protects fundamental rights.

Note

Selections from Universal Declaration of Human Rights

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude.

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law.

The justice view of moral behavior is based on the belief that ethical decisions treat people impartially and fairly, according to legal rules and standards. This approach evaluates the ethical aspects of any decision on the basis of whether it is "equitable" for everyone affected.[134] Justice issues in organizations are often addressed on four dimensions—procedural, distributive, interactional, and commutative.[135]

• In the justice view ethical behavior treats people impartially and fairly.

Procedural justice involves the degree to which policies and rules are fairly applied to all individuals. For example, does a sexual harassment charge levied against a senior executive receive the same full hearing as one made against a firstlevel supervisor? Does a woman with the same qualifications and experience as a man receive the same consideration for decisions regarding hiring or promotion? Distributive justice involves the degree to which outcomes are allocated fairly among people and without respect to individual characteristics based on ethnicity, race, gender, age, or other particularistic criteria. For example, are members of minority groups adequately or proportionately represented in senior management positions? Do universities allocate a proportionate share of athletic scholarships to males and females? Interactional justice involves the degree to which people treat one another with dignity and respect. For example, does a bank loan officer take the time to fully explain to an applicant why he or she was turned down for a loan?[136] Commutative justice focuses on the fairness of exchanges or transactions. According to this principle, the exchange is deemed to be fair if all parties enter into it freely, have access to relevant and available information, and obtain some type of benefit from the transaction.[137]

• Procedural justice is concerned that policies and rules are fairly applied.

• Distributive justice focuses on the degree to which outcomes are distributed fairly.

• Interactional justice is the degree to which others are treated with dignity and respect.

• Commutative justice is the degree to which an exchange or a transaction is fair to all parties.

Examining issues through all four viewpoints helps to provide a more complete picture of the ethicality of a decision than merely relying on a single point of view. However, each viewpoint has some drawbacks that should be recognized.

The utilitarian view relies on the assessment of future outcomes that are often difficult to predict and that are tough to measure accurately. What is the economic value of a human life when deciding how rigid safety regulations need to be, especially when it is unclear exactly how many individuals might be affected? The individualism view presumes that individuals are self-regulating; however, not everyone has the same capacity or desire to control their behaviors. Even if only a few individuals take advantage of the freedom allowed under this perspective, such instances can disrupt the degree of trust that exists within a business community and make it difficult to predict how others will act.

The moral rights view provides for individual rights, but does not ensure that the outcomes associated with protecting those rights are beneficial to the majority of society. What happens when someone's right to privacy makes the workplace less safe for everyone? Finally, the justice view places an emphasis on fairness and equity, but this viewpoint raises the question of which type of justice is paramount. Is it more important to ensure that everyone is treated exactly the same way (procedural justice) or to ensure that those from different backgrounds are adequately represented in terms of the final outcome (distributive justice)?

Picture the situation: a 12-year-old boy is working in a garment factory in Bangladesh. He is the sole income earner for his family. He often works 12-hour days and was once burned quite badly by a hot iron. One day he is fired. His employer had been given an ultimatum by a major American customer: "no child workers if you want to keep our contracts." The boy says: "I don't understand. I could do my job very well. I need the money."

Should the boy be allowed to work? This difficult and perplexing situation is one example of the many ethics challenges faced in international business. Former Levi Strauss CEO Robert Haas once said that an ethical problem "becomes even more difficult when you overlay the complexities of different cultures and values systems that exist throughout the world."[138]

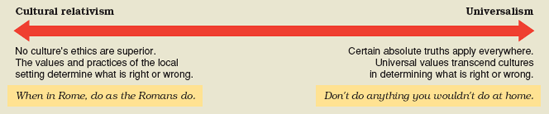

Those who believe that behavior in foreign settings should be guided by the classic rule of "when in Rome, do as the Romans do" reflect an ethical position known as cultural relativism.[139] This is the belief that there is no one right way to behave and that ethical behavior is always determined by its cultural context. An American international business executive guided by rules of cultural relativism, for example, would argue that the use of child labor is acceptable in another country as long as it is consistent with local laws and customs.

• Cultural relativism suggests there is no one right way to behave; ethical behavior is determined by its cultural context.

• Universalism suggests ethical standards apply absolutely across all cultures.

Figure 3.2 contrasts cultural relativism with universalism. Universalism is an absolutist ethical position suggesting that if a behavior or practice is not okay in one's home environment, it is not an acceptable practice anywhere else. In other words, ethical standards are universal and should apply absolutely across cultures and national boundaries. In the former example, the American executive would not do business in a setting where child labor was used, since it is unacceptable at home. Critics of such a universal approach claim that it is a form of ethical imperialism, an attempt to impose one's ethical standards on others.

Source: Developed from Thomas Donaldson, "Values in Tension: Ethics Away from Home," Harvard Business Review, vol. 74 (September–October 1996), pp. 48–62.

• Ethical imperialism is an attempt to impose one's ethical standards on other cultures.

Business ethicist Thomas Donaldson finds fault with both cultural relativism and ethical imperialism. He argues instead that certain fundamental rights and ethical standards can be preserved at the same time that values and traditions of a given culture are respected.[140] The core values or "hyper-norms" that should transcend cultural boundaries focus on human dignity, basic rights, and good citizenship. Donaldson believes international business behaviors can be tailored to local and regional cultural contexts while still upholding these core values. In the case of child labor, the American executive might take steps so that any children working in a factory under contract to his or her business would be provided daily scheduled schooling as well as employment.[141]

Note

✓Learning Check

Study Question 1

What is ethical behavior?

Be sure you can ✓ define ethics ✓ explain why obeying the law is not always the same as behaving ethically ✓explain the difference between terminal and instrumental values ✓identify the four alternative views of ethics ✓ contrast cultural relativism with universalism

A college student gets a job offer and accepts it, only to get a better offer two weeks later. Is it right for her to renege on the first job to accept the second? A student knows that in a certain course his roommate submitted a term paper purchased on the Internet. Is it right for him not to tell the instructor? One student tells another that a faculty member promised her a high final grade in return for sexual favors. Is it right for him to inform the instructor's department head?

The real test of ethics occurs when individuals encounter a situation that challenges their personal values and standards. Often ambiguous and unexpected, these ethical challenges are inevitable. Everyone has to be prepared to deal with them, even students.

• An ethical dilemma is a situation that offers potential benefit or gain and that may also be considered unethical.

An ethical dilemma is a situation that requires a choice regarding a possible course of action that, although offering the potential for personal or organizational benefit, or both, may be considered unethical. It is often a situation in which action must be taken but for which there is no clear consensus on what is "right" and "wrong." An engineering manager speaking from experience sums it up this way: "I define an unethical situation as one in which I have to do something I don't feel good about."[142] Some examples of ethical dilemmas that managers face include:[143]

Discrimination —Your boss suggests that it would be a mistake to hire a job candidate due to the individual's race, religion, gender, or age because your traditional customers might be uncomfortable with the individual.

Sexual harassment —A female subordinate asks you to discipline a coworker that she claims is making inappropriate sexual remarks that make her feel uncomfortable. The coworker, your friend, says that he was just kidding around and asks you not to take any action that would go on his permanent record.

Conflicts of interest —You are working in a foreign country and are offered an expensive gift in return for making a decision favorable to the gift giver. You know that such exchanges are common practice in this particular culture and that several of your colleagues have accepted similar gifts in the past.

Product safety —Your company is struggling financially and can make one of its major products more cheaply by purchasing lower-quality materials, although doing so would marginally increase the risk of consumer injury.

Use of organizational resources —Your company provides you with a laptop computer so that you can do work at home after hours. Your wife likes that computer better than hers, and asks if she can use it for her online business during the evening and on weekends.

It is almost too easy to confront ethical dilemmas from the safety of a textbook or a classroom discussion. In real life it's often a lot harder to consistently choose ethical courses of action. We end up facing ethical dilemmas at unexpected and inconvenient times, the events and facts can be ambiguous, and other performance pressures can be unforgiving and intense. Is it any surprise, then, that 56% of U.S. workers in one survey reported feeling pressured to act unethically in their jobs? Or that 48% said they had committed questionable acts within the past year?[144]

Management Smarts 3.1 presents a sevenstep checklist for dealing with an ethical dilemma. It is a way to double-check the ethics of decisions before taking action. Step 6 highlights a key test: the risk of public disclosure. Asking and answering the recommended spotlight questions is a powerful way to test whether a decision is consistent with your personal ethical standards. They're worth repeating: "How will I feel if my family finds out about my decision, or if it's reported in the local newspaper or posted on the Internet?"

Increased awareness of the typical influences on ethical decision making can help you better deal with ethical pressures and dilemmas. These influences come from personal factors, the situational context, organizational culture, and the external environment.

Standing up for what you believe in isn't always easy, especially in a social context full of contradictory or just plain bad advice. Consider these words from a commencement address delivered some years ago at a well-known school of business administration. "Greed is all right," the speaker said. "Greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself." The students, it is reported, greeted these remarks with laughter and applause. The speaker was Ivan Boesky, once considered the "king of the arbitragers."[145] It wasn't long after his commencement speech, however, that Boesky was arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced to prison for trading on inside information.

Values, family, religion, and personal needs all help determine a person's ethics. Managers who lack a strong and clear set of personal ethics will find that their decisions vary from situation to situation. Those with solid ethical frameworks, ones that provide personal rules or strategies for ethical decision making, will act more consistently and confidently. The foundations for these frameworks rest with individual character and personal values that give priority to such virtues as honesty, fairness, integrity, and self-respect. These moral anchors can help us make ethical decisions even when circumstances are ambiguous and situational pressures are difficult.

• An ethical framework is a personal rule or strategy for making ethical decisions.

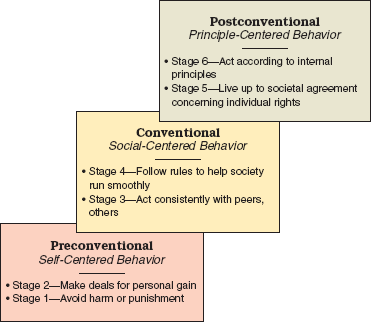

Lawrence Kohlberg describes the three levels of moral development shown in Figure 3.3—preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.[146] There are two stages in each level, and Kohlberg believes that we move step by step through them as we grow in maturity and education. Most people operate either from a preconventional or conventional level of moral development; very few consistently operate at the postconventional level. And because individuals make decisions from different levels of moral development, they may approach the same ethical dilemma very differently.

In Kohlberg's preconventional level of moral development the individual is selfcentered. Moral thinking is largely limited to issues of punishment, obedience, and personal interest. Decisions made in the preconventional stages of moral development are likely to be directed toward achieving personal gain or avoiding punishment and are based on obedience to rules.

In the conventional level of moral development, the individual is more social-centered. Decisions made in these stages are likely to be based on following social norms, meeting the expectations of others, and living up to agreed upon obligations.

At the postconventional level of moral development, the individual is strongly principle-centered. This is where a strong ethics framework is evident and the individual is willing to break with norms and conventions, even laws, to make decisions consistent with personal principles. Kohlberg believes that only a small percentage of people progress to the postconventional stages. An example might be the student who passes on an opportunity to cheat on a take-home examination because he or she believes it is wrong, even though the individual knows that most of the other students will cheat, that there is almost no chance of getting caught, and that the consequence of not cheating will be getting a lower grade on the test. Another example might be someone who refuses to use pirated computer software easily available through the Internet and social networks, preferring to purchase them and respect others' intellectual property rights.

Ethical dilemmas often appear unexpectedly or in ambiguous conditions; we're caught off guard and struggle to respond. Other times, we might even fail to see that an issue or a situation has an ethics component. This may happen, for example, when students find cheating so commonplace on campus that it becomes an accepted standard of behavior. Scholars use the concept of ethics intensity or issue intensity to describe the extent to which a situation is perceived to pose important ethics challenges.[147]

• Ethics intensity or issue intensity indicates the degree to which an issue or a situation is recognized to pose important ethical challenges.

The conditions that raise the ethics intensity of a situation include the magnitude, probability, and immediacy of any potential harm, the proximity and concentration of the effects, and social consensus. A decision situation will elicit greater ethical attention when the potential harm is perceived as great, likely, and imminent, the potential victims are visible and close by, and there is more social agreement on what is good or bad about what is taking place. For example, how does the issue of pirated music downloads stack up on each of these ethics intensity factors? Can we say that low ethics intensity contributes to the likelihood of music pirating? In general, the greater the ethical intensity of the situation, the more aware the decision maker is about ethics issues and the more likely that his or her behavior will be ethical.

The culture and values of an organization are important influences on ethics in the workplace. How a supervisor acts, what he or she requests, and what is rewarded or punished can certainly affect how others behave. The expectations of peers and group norms are likely to have a similar impact. In some cases, members will not be fully accepted as part of the team if they do not participate in actions that outsiders might consider unethical—for example, slacking off or abusing phone privileges. In other cases, the ethics culture sets high standards and may even push people to behave more ethically than they otherwise would.

Some organizations try to set the ethics culture by issuing formal policy statements and guidelines. Consider the story behind The Body Shop, quite well known for its entrepreneurial beginnings and socially responsible business model. Right from her first store in Brighton, England, the late founder Dame Anita Roddick built an organizational culture around the value of "profits with principles." She created an 11-point charter to guide the company's employees. It included this statement: "Honesty, integrity and caring form the foundations of the company and should flow through everything we do—we will demonstrate our care for the world in which we live by respecting fellow human beings, by not harming animals, by preserving our forests."[148] Now owned by L'Oreal, The Body Shop's charter still communicates corporate expectations to employees in more than 2,100 shops in 55 countries.[149]

Wherever they operate, domestically or internationally, organizations are influenced by government laws and regulations as well as social norms and expectations. Laws interpret social values to define appropriate behaviors for organizations and their members; regulations help governments monitor these behaviors and keep them within acceptable standards. For example, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 makes it easier for U.S. corporate executives to be tried and sentenced to jail for financial misconduct. It also created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board and set a new standard for auditors to verify reporting processes in the companies they audit.

The climate of competition in an industry also sets a standard of behavior for those who hope to prosper within it. Sometimes the pressures of competition contribute to the ethical dilemmas of managers. Former American Airlines president Robert Crandall once telephoned Howard Putnam, then president of the now-defunct Braniff Airlines. Both companies were suffering from money-losing competition on routes from their home base of Dallas. A portion of their conversation follows.[150] Putnam: Do you have a suggestion for me? Crandall: Yes ... Raise your fares 20 percent. I'll raise mine the next morning. Putnam: Robert, we— Crandall: You'll make more money and I will, too. Putnam: We can't talk about pricing. Crandall: Oh, Howard. We can talk about anything we want to talk about. In fact, the U.S. Justice Department strongly disagreed with Crandall. It alleged that his suggestion of a 20% fare increase amounted to an illegal attempt to monopolize airline routes. The suit was later settled when Crandall agreed to curtail future discussions with competitors about fares.

Consider the possibility of being asked to place a bid for a business contract using insider information, paying bribes to obtain foreign business, or falsifying expense account bills. "How," you should be asking, "do people explain doing things like this?" In fact, there are at least four common rationalizations that may be used to justify misconduct in situations that pose ethical dilemmas.[151]

Convincing yourself that a behavior is not really illegal.

Convincing yourself that a behavior is in everyone's best interests.

Convincing yourself that nobody will ever find out what you've done.

Convincing yourself that the organization will "protect" you.

After doing something that might be considered unethical, a rationalizer says: "It's not really illegal." This expresses a mistaken belief that one's behavior is acceptable, especially in ambiguous situations. When dealing with shady or borderline situations in which you are having a hard time precisely determining right from wrong, the advice is quite simple: When in doubt about a decision to be made or an action to be taken, don't do it.

Another common statement by a rationalizer is "It's in everyone's best interests." This response involves the mistaken belief that because someone can be found to benefit from the behavior, the behavior is also in the individual's or the organization's best interests. Overcoming this rationalization depends in part on the ability to look beyond short-run results to address longer-term implications, and to look beyond results in general to the ways in which they are obtained. In response to the question "How far can I push matters to obtain this performance goal?" the best answer may be, "Don't try to find out."

Sometimes rationalizers tell themselves that "no one will ever know about it." They mistakenly believe that a questionable behavior is really "safe" and will never be found out or made public. Unless it is discovered, the argument implies, no crime was really committed. Lack of accountability, unrealistic pressures to perform, and a boss who prefers "not to know" can all reinforce such thinking. In this case, the best deterrent is to make sure that everyone knows that wrongdoing will be punished whenever it is discovered.

Finally, rationalizers may proceed with a questionable action because of a mistaken belief that "the organization will stand behind me." This is misperceived loyalty. The individual believes that the organization's best interests stand above all others. In return, the individual believes that top managers will condone the behavior and protect the individual from harm. But loyalty to the organization is not an acceptable excuse for misconduct; it should not stand above the law and social morality.

Note

✓Learning Check

Study Question 2

How do ethical dilemmas complicate the workplace?

Be sure you can ✓ define ethical dilemma and give workplace ✓ examples ✓ identify Kohlberg's stages of moral development explain how ethics intensity influences ethical decision making explain how ethics decisions are influenced by an organization's culture and the external environment ✓ list four common rationalizations for unethical behavior

Item: Bernard Madoff masterminded the largest fraud in history by swindling billions of dollars from thousands of investors. Item: Company admits overcharging consumers and insurers more than $13 million for repairs to damaged rental cars. Item: Former Tyco CEO Dennis Kozlowski convicted on 22 counts of grand larceny, fraud, conspiracy, and falsifying business records. Item: U.S. lawmakers charge that BP was negligent in inspecting oil pipelines, and that workers complained of excessive cost-cutting and pressures to falsify maintenance records. Item: Alcoa charged with paying illegal "kickbacks" to an official in Bahrain.[152]

We all know that news from the corporate world is not always positive when it comes to ethics. But as quick as we are to recognize the bad, we shouldn't forget that there is a lot of good news, too. There are many organizations, like Stonyfield Farm as featured in the chapter opener, whose leaders and members set high ethics standards for themselves and others.

Ethics training takes the form of structured programs to help participants understand the ethical aspects of decision making. It is designed to help people incorporate high ethical standards into their daily behaviors. The Lockheed Martin Company, an aerospace, defense, security, and technology firm based in Maryland, requires all its employees to complete ethics awareness training on an annual basis. The company also produces short videos called the "Integrity Minute" as a complement to the training. The videos highlight key ethics topics such as harassment, conflicts of interest, gifts, and business courtesies. The company also shows its commitment to ethics and ethics training by appointing a vice president of ethics and business conduct as well as local ethics officers.[153]

• Ethics training seeks to help people understand the ethical aspects of decision making and to incorporate high ethical standards into their daily behavior.

There are lots of options in ethics training. College curricula include course work on ethics, and seminars on the topic are popular in the corporate world. But regardless of where or how the ethics training is conducted, it is important to keep things in perspective. Training is an ethics development aid; it isn't a guarantee of ethical behavior. A banking executive once summed things up this way: "We aren't teaching people right from wrong—we assume they know that. We aren't giving people moral courage to do what is right—they should be able to do that anyhow. We focus on dilemmas."[154]

Ethics training often includes the communication of a code of ethics, a formal statement of an organization's values and ethical principles. Such codes are important anchor points in professions such as engineering, medicine, law, and public accounting. In organizations, they identify expected behaviors in such areas as general citizenship, the avoidance of illegal or improper acts in one's work, and good relationships with customers. Specific guidelines are often set for bribes and kickbacks, political contributions, honesty of books or records, customer–supplier relationships, coworker relationships, and confidentiality of corporate information.

• A code of ethics is a formal statement of values and ethical standards.

Ethics codes are common in the complicated world of international business. For example, global manufacturing at Gap, Inc., is governed by a Code of Vendor Conduct.[155] The document addresses discrimination—"Factories shall employ workers on the basis of their ability to do the job, not on the basis of their personal characteristics or beliefs"; forced labor—"Factories shall not use any prison, indentured or forced labor"; working conditions—"Factories must treat all workers with respect and dignity and provide them with a safe and healthy environment"; and freedom of association—"Factories must not interfere with workers who wish to lawfully and peacefully associate, organize or bargain collectively."

But even though they have ethics codes in place, it is hard for even the most ethically committed global firms to police practices when they have many, even hundreds, of suppliers from different parts of the world. You might remember the recall of some 25 million toys, the large majority of which were made in China. Toy sellers like Wal-Mart have ethics codes and the U.S. government has toy safety regulations. Yet, the tainted toys got through to customers. Wal-Mart responded to the crisis by tightening its code and requiring suppliers to meet safety standards that are even higher than U.S. government requirements.[156]

Although ethics training and codes of ethical conduct are helpful, they cannot guarantee ethical behavior in organizations. Ultimately, the issue boils down to individual character; there is no replacement for effective management practices that staff organizations with honest people. And, there is no replacement for having ethical leaders that set positive examples and always act as ethical role models.

Management scholar Archie Carroll makes a distinction between immoral, amoral, and moral managers.[157] The immoral manager chooses to behave unethically. He or she does something purely for personal gain and knowingly disregards the ethics of the action or situation. The amoral manager also disregards the ethics of an act or a decision, but does so unintentionally or unknowingly. This manager simply fails to consider the ethical consequences of his or her actions, and typically uses the law as a guideline for behavior. The moral manager considers ethical behavior as a personal goal. He or she makes decisions and acts in full consideration of ethical issues. In Kohlberg's terms, this manager is likely to be operating at the postconventional or principled level of moral development.[158]

• An immoral manager chooses to behave unethically.

• An amoral manager fails to consider the ethics of her or his behavior.

• A moral manager makes ethical behavior a personal goal.

Think about these three types of managers and how common they are in the real world of work. Although it may seem surprising, Carroll suggests that most managers act amorally. Though well intentioned, they remain mostly uninformed or undisciplined in considering the ethical aspects of our behavior. The moral manager, like Gary Hirshberg in the chapter opener, by contrast, is an ethics leader who always serves as a positive role model.

Agnes Connolly pressed her employer to report two toxic chemical accidents.

Dave Jones reported that his company was using unqualified suppliers in the construction of a nuclear power plant.

Margaret Newsham revealed that her firm was allowing workers to do personal business while on government contracts.

Herman Cohen charged that the ASPCA in New York was mistreating animals.

Barry Adams complained that his hospital followed unsafe practices.[159]

These persons from different work settings and linked to different issues share two important things in common. First, each was a whistleblower that exposed misdeeds in their organizations in order to preserve ethical standards and protect against further wasteful, harmful, or illegal acts.[160] Second, each was fired from their job.

• A whistleblower exposes the misdeeds of others in organizations.

At the same time that we can admire whistleblowers for their ethical stances, there is no doubt that they face risks of impaired career progress and other forms of organizational retaliation, up to and including termination. Although laws such as the Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989 offer some defense against "retaliatory discharge," legal protections for whistleblowers are continually being tested in court and many consider them inadequate.[161] Laws vary from state to state, and federal laws mainly protect government workers.

Research by the Ethics Resource Center has found that some 44% of workers in the United States fail to report the wrongdoings they observe at work. The top reasons are "(1) the belief that no corrective action would be taken and (2) the fear that reports would not be kept confidential."[162] Within an organization, furthermore, typical barriers to whistleblowing include a strict chain of command that makes it hard to bypass the boss; strong work group identities that encourage loyalty and self-censorship; and ambiguous priorities that make it hard to distinguish right from wrong.[163]

Note

✓Learning Check

Study Question 3

How can high ethical standards be maintained?

Be sure you can ✓ compare and contrast ethics training and codes of ethical conduct as methods for encouraging ethical behavior in organizations ✓ differentiate between amoral, immoral, and moral management ✓ define whistleblower ✓ identify common barriers to whistleblowing and the factors to consider when determining whether whistleblowing is appropriate

Sustainability is an important word in management these days, and Procter & Gamble defines it as acting in ways that help ensure "a better quality of life for everyone now and for generations to come."[164] Think sustainability opportunities when you hear terms like alternative energy, recycling, and waste avoidance; think sustainability problems when you ponder the aftermath of the enormous Gulf of Mexico oil spill or read about hazardous chemicals in our medicines and food sources. We'll talk more about such issues in the next chapter on environment, sustainability, and innovation. But for now, they are all part and parcel of an important management concept known as corporate social responsibility. Also called CSR for short, it describes the obligation of an organization to act in ways that serve both its own interests and the interests of society at large.

• Sustainability in management means acting in ways that support a high quality of life for present and future generations.

• Corporate social responsibility is the obligation of an organization to serve the interests of society in addition to its own interests.

It is common for managers to make decisions while paying attention to what accountants call the "bottom line"—that is, considering how the decision will affect the profitability of the firm. But as introduced in the chapter opening example of Stonyfield Farm, more and more today we talk about the triple bottom line —a concept that focuses on a firm's economic, social, and environmental performance.[165] Some call this triple bottom line the concern for the "3 P's"—profit, people, and planet.[166] You might think of it more generally as acting with a sense of corporate social responsibility. And, by the way, that's most likely how you'd like your future employers to behave. "Students nowadays want to work for companies that help enhance the quality of life in their surrounding community," says one observer.[167] And in one survey 70% of students report that "a company's reputation and ethics" was "very important" when deciding whether or not to accept a job offer; in another survey 79% of 13–25 year olds say they "want to work for a company that cares about how it affects or contributes to society."[168] Here are some examples that seem to meet this test.[169]

• The triple bottom line evaluates organizational performance on economic, social, and environmental criteria.

Trish Karter, who co-founded the Dancing Deer Bakery in Boston, found a winning recipe for social entrepreneurship. She hires people who lack skills, trains them, and provides them with a financial stake in the company. She also donates 35% of company proceeds to fund action programs to end family homelessness.

Ori Sivan started a Chicago company called Greenmaker Building Supply. It supplies builders with a variety of green products—including kitchen tiles from coal combustion residue, countertops from recycled paper, and insulation made from old blue jeans.

Carol Tienken worked 18 years for Polaroid Corporation before joining the nonprofit Greater Boston Food Bank. It serves 83,000 people each week. Tienken says: "At Polaroid, it was cameras and film. Nobody was going to die or go hungry. This business does make a difference."

Deborah Sardone owns a housekeeping service in Texas. Noticing that clients with cancer really struggled with chores, she started Cleaning for a Reason. The nonprofit organization networks with cleaning firms around the country to provide free home cleaning to cancer patients.

• Stakeholders are the persons, groups, and other organizations that are directly affected by the behavior of the organization and that hold a stake in its performance.

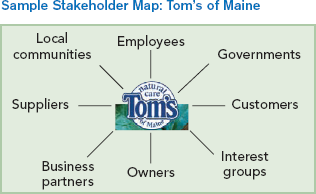

Any discussion of social responsibility needs to recognize that organizations exist in a network of stakeholders. These are the persons, groups, and other organizations that are directly affected by the behavior of the organization and that hold a stake in its performance.[170] Typical organizations have many stakeholders such as owners or shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, business partners, government representatives and regulators, and community members. It can be helpful to identify them on a stakeholder map, such as the one in the Tom's of Maine example.

A key difficulty in stakeholder management is dealing with multiple stakeholders who make conflicting demands on the organization. For example, customers may demand lowcost products, while environmental activists may pressure the company to utilize manufacturing processes that make products more expensive. Or, shareholders may push the company to cut employment costs in order to improve the organization's financial performance, while employees may demand higher levels of healthcare benefits or protection against layoffs.

One way that managers can deal with conflicting stakeholder demands is to evaluate those demands along three criteria—the power of the stakeholder, the legitimacy of the demand, and the urgency of the issue.[171] Stakeholder power refers to the capacity of the stakeholder to positively or negatively affect the operations of the organization. Demand legitimacy, which reflects the extent to which the stakeholder's demand is perceived as valid and the extent to which the demand comes from a party with a legitimate stake in the organization. Issue urgency deals with the extent to which the issues require immediate attention or action.

• Stakeholder power refers to the capacity of the stakeholder to positively or negatively affect the operations of the organization.

• Demand legitimacy indicates the validity and legitimacy of a stakeholder's interest in the organization.

• Issue urgency indicates the extent to which a stakeholder's concerns need immediate attention.

Corporate social responsibility gets lots of stakeholder attention. Consumers, activist groups, nonprofit organizations, employees, and governments are often vocal and influential in pushing organizations toward socially responsible practices. In today's information age, business activities are increasingly transparent. Irresponsible practices are difficult to hide for long, no matter where in the world they take place. Not only do news organizations find and disseminate information on bad practices, activist organizations do the same. They also lobby, campaign, and actively pressure organizations to respect and protect everything from human rights to the natural environment.[172]

It may seem that corporate social responsibility is one of those concepts that most everyone agrees upon. But stakeholders can hold differing views on the ethicality of an organization's actions.[173] When the pros and cons of CSR are debated in academic and public-policy circles, those holding to a classical view take a stand against making corporate social responsibility a business priority while those holding to a socioeconomic view advocate for it.[174]

The classical view of CSR holds that management's only responsibility in running a business is to maximize profits. In other words, "the business of business is business," and the principal obligation of management should always be to owners and shareholders. This classical view takes a very narrow stakeholder perspective and puts the focus on the single bottom line of financial performance. It is supported by Milton Friedman, a respected economist and Nobel Laureate. He says: "Few trends could so thoroughly undermine the very foundations of our free society as the acceptance by corporate officials of social responsibility other than to make as much money for their stockholders as possible."[175]

• The classical view of CSR is that business should focus on profits.

The arguments against corporate social responsibility include fears that its pursuit will reduce business profits, raise business costs (reducing competitiveness with foreign firms), dilute business purpose, and/or give business too much social power without any specific accountability to the public. Although not against corporate social responsibility in its own right, Friedman and other proponents of the classical view believe that society's interests are best served in the long run by executives who focus on maximizing their firm's profits.

The socioeconomic view of CSR holds that managers must be concerned with the organization's effect on the broader social welfare and not just with corporate profits. This view takes a broad stakeholder perspective and puts the focus on an expanded (triple) bottom line that includes not just financial performance but also social and environmental performance. It is supported by Paul Samuelson, another distinguished economist and Nobel Laureate. He says: "A large corporation these days not only may engage in social responsibility, it had damn well better try to do so."[176]

• The socioeconomic view of CSR is that business should focus on broader social welfare as well as profits.

Among the arguments in favor of corporate social responsibility are that it will enhance long-run profits, improve the public image of the business, make the organization a more attractive place to work, and help avoid government regulation. Furthermore, because society has provided the infrastructure that allows businesses to operate, businesses need to take actions that are in alignment with society's best interests. Thus, business executives have ethical obligations to ensure that their firms act responsibly and in the interests of society at large.

There is little doubt today that the public at large wants businesses and other organizations to act with genuine social responsibility. Also, a growing body of research links social responsibility and financial performance. One report showed that S&P 500 firms with strong commitments to corporate philanthropy outperform in respect to operating earnings.[177] More generally, research indicates that social responsibility is often associated with strong financial performance; at worst, corporate social responsibility appears to have no adverse financial impact.[178] Thus, the argument that acting with a commitment to social responsibility will negatively affect the "bottom line" is hard to defend. Instead, evidence points toward a virtuous circle in which corporate social responsibility leads to improved financial performance for the firm, and this in turn leads to more socially responsible actions in the future.[179]

• The virtuous circle occurs when CSR improves financial performance, which leads to more CSR.

If we are to get serious about social responsibility, we need to get rigorous about measuring corporate social performance and holding business leaders accountable for the results. A social responsibility audit can be used at regular intervals to report on and systematically assess an organization's performance in various areas of corporate social responsibility.

• A social responsibility audit assesses an organization's accomplishments in areas of social responsibility.

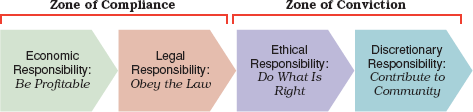

The social performance of business firms ranges from compliance —acting to avoid adverse consequences—to conviction —acting to create positive impact.[180] As shown in Figure 3.4, this performance can be evaluated on four criteria for evaluating socially responsible practices: economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary.[181]

Economic responsibility—Is the organization profitable?

Legal responsibility—Is the organization obeying the law?

Ethical responsibility—Is the organization doing what is "right"?

Discretionary responsibility—Is the organization contributing to the broader community?

An organization is meeting its economic responsibility when it earns a profit through the provision of goods and services desired by customers. While it might seem unusual to focus on economic performance, this is the foundation on which all the other types of responsibility rest. If a firm is not financially viable, it will not be able to take care of its owners or employees or engage in any of the other aspects of CSR. Legal responsibility is fulfilled when an organization operates within the law and according to the requirements of various external regulations. An organization meets its ethical responsibility when its actions voluntarily conform not only to legal expectations but also to the broader values and moral expectations of society. The highest level of social performance comes through the satisfaction of discretionary responsibility. At this level, the organization moves beyond basic economic, legal, and ethical expectations to provide leadership in advancing the well-being of individuals, communities, and society as a whole.

The decisions of people working at all levels in organizations ultimately determine whether or not practices are socially responsible. At the executive level these are "strategic" decisions designed to move the organization forward in its environment according to a long-term plan.[182] Figure 3.5 describes four corporate social responsibility strategies, with the commitment to social performance increasing as the strategy shifts from "obstructionist" at the lowest end to "proactive" at the highest.[183]

The obstructionist strategy ("Fight social demands") focuses mainly on economic priorities in respect to social responsibility. Social demands lying outside the organization's perceived self-interests are resisted. If the organization is criticized for wrongdoing, it can be expected to deny the claims. For example, cigarette manufacturers in the United States tried to minimize the negative health effects of smoking for decades until indisputable evidence became available.

• An obstructionist strategy avoids social responsibility and reflects mainly economic priorities.

A defensive strategy ("Do the minimum legally required") seeks to protect the organization by doing the minimum legally necessary to satisfy expectations. Corporate behavior at this level conforms only to legal requirements, competitive market pressure, and perhaps activist voices. If criticized, wrongdoing on social responsibility matters is likely to be denied. For example, car dealers are required to provide certain information to customers concerning loans they may be receiving. Some car dealers make sure their customers fully understand the information while other dealers gloss over the detailed information in hopes the customer will not realize the negative aspects of the car loan.

• A defensive strategy seeks protection by doing the minimum legally required.

Organizations pursuing an accommodative strategy ("Do the minimum ethically required") accept their social responsibilities. They try to satisfy economic, legal, and ethical criteria. Corporate behavior at this level is consistent with society's prevailing norms, values, and expectations, often reflecting the demands of outside pressures. An oil firm, for example, may be willing to "accommodate" with appropriate cleanup activities when a spill occurs; yet it may remain quite slow in taking actions to prevent spills in the first place.

• An accommodative strategy accepts social responsibility and tries to satisfy economic, legal, and ethical criteria.

The proactive strategy ("Take leadership in social initiatives") is designed to meet all prior criteria of social performance, and it also requires engaging in discretionary actions related to CSR. Corporate behavior at this level takes preventive action to avoid adverse social impacts from company activities, and it takes the lead in identifying and responding to emerging social issues. Interface's effort to proactively restructure its production processes in order to avoid having a negative effect on the environment is an example of this type of strategy.

• A proactive strategy meets all the criteria of social responsibility, including discretionary performance.

When you read and hear about business ethics failures and poor corporate social responsibility, issues relating to corporate governance are often raised. The term refers to the active oversight of management decisions and company actions by boards of directors.[184] Businesses are required by law to have boards of directors that are elected by stockholders to represent their interests. The governance exercised by these boards most typically involves hiring, firing, and compensating the CEO; assessing strategy; and verifying financial records. The expectation is that board members will hold management accountable for ethical and socially responsible leadership.[185]

• Corporate governance is the oversight of top management by a board of directors.

It is tempting to think that corporate governance is a clear-cut way to ensure that organizations exhibit social responsibility and that their members always act ethically. But the recent financial crisis and related banking scandals show once again that corporate governance can be inadequate and in some cases ineffectual. Where, you might ask, were the boards when such situations were first developing?

When corporate failures and controversies occur, weak governance often gets blamed. And when it does, you will sometimes see government stepping in to try to correct things for the future. In addition to holding hearings, as in the case of "bail-out" loans to U.S. automakers and banks, governments also pass laws and establish regulating agencies in attempts to better control and direct business behavior. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, mentioned earlier, was passed by Congress in response to public outcries over major ethics and business scandals. Its goal is to ensure that top managers properly oversee and are held accountable for the financial conduct of their organizations.

Even as one talks about corporate governance reform and the accountability of top management, it is important to remember that all managers must accept personal responsibility for doing the "right" things.[186] Figure 3.6 highlights what might be called the need for ethics self-governance in day-to-day work behavior. It is not enough to fulfill one's performance accountabilities; they must be fulfilled in an ethical and socially responsible manner. The full weight of this responsibility holds in every organizational setting, from small to large and from private to nonprofit, and at every managerial level from top to bottom. There is no escaping the ultimate reality—being a manager at any level is a very socially responsible job!

Note

✓Learning check

Study Question 4

What are corporate social responsibility and governance?

Be sure you can ✓ discuss stakeholder management and identify key organizational stakeholders ✓ define corporate social responsibility ✓ summarize arguments for and against corporate social responsibility ✓ identify four criteria for measuring corporate social performance ✓ explain four possible social responsibility strategies ✓ define corporate governance and discuss its importance