5 Portfolio management cycles

5.1 PURPOSE OF THIS CHAPTER

This chapter re-introduces the two portfolio management cycles and considers the main approaches to implementing portfolio management and how to sustain progress, including the role of organizational energy in ensuring success. The discussion then lays the foundation for more detailed consideration of the portfolio management practices in Chapters 6 and 7 by examining the purpose of the definition and delivery cycles, what happens when they are managed effectively and what happens when this is not the case.

5.2 THE PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT CYCLES

The portfolio management cycles were introduced in Chapter 2 and are illustrated in Figure 0.1.

Portfolio management does not have a mandated start point, middle or end – rather:

![]() The definition cycle contains a series of broadly sequential practices (i.e. ‘understand’ generally comes before ‘categorize’, which usually comes before ‘prioritize’ etc.), although in practice they will often overlap.

The definition cycle contains a series of broadly sequential practices (i.e. ‘understand’ generally comes before ‘categorize’, which usually comes before ‘prioritize’ etc.), although in practice they will often overlap.

![]() The delivery cycle is different in that the practices here are undertaken broadly simultaneously; but the cycle analogy is still applicable as the individual initiatives go through the programme or project lifecycle, and as portfolio delivery is linked to the strategic planning, financial and risk management cycles.

The delivery cycle is different in that the practices here are undertaken broadly simultaneously; but the cycle analogy is still applicable as the individual initiatives go through the programme or project lifecycle, and as portfolio delivery is linked to the strategic planning, financial and risk management cycles.

5.3 IF THERE IS NO DEFINED START, HOW SHOULD PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT BE IMPLEMENTED?

Different organizations have different reasons for implementing portfolio management, including: a major cut in budgets forcing questions about how to achieve deficit reduction without impacting adversely on service delivery; an external event such as a new competitor or regulatory change; a new chief executive officer; or the realization that the organization’s track record in delivery of change initiatives and benefits realization requires corrective action. Similarly, organizations have different starting points reflecting their existing PPM capability, organizational culture, governance structure, financial position and strategic objectives. The different drivers behind the adoption of portfolio management, and the differing conditions in which it is undertaken, will influence the way in which portfolio management is implemented. Three broad approaches can be identified as outlined in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Approaches to implementing portfolio management

|

Big bang |

Implementing portfolio management is viewed as a business change programme in its own right and is planned with:

Here a time-bound implementation phase is followed by live running encompassing all portfolio definition and delivery practices. |

|

Evolution |

Here a more evolutionary or incremental approach is taken, starting with areas of greatest need or those where rapid progress can be made. The organization’s approach to portfolio management then evolves to reflect its needs, opportunities and lessons learned. |

|

Ad hoc |

As with the evolutionary approach, there is no detailed master plan, but there is no expectation that the approach will develop and no commitment to capturing lessons learned to inform development. Instead, implementation is more opportunistic. |

It is important to emphasize that there is no one right way to implement portfolio management – it all depends on the circumstances.

The ‘big bang’ approach is most appropriate where top-down approaches to strategy formulation are applied, where the environment is relatively stable and where PPM is already relatively mature.

In other situations, a staged, incremental or evolutionary approach will be more appropriate – building on initial developments in one part of the organization and focusing on specific processes to demonstrate the value of a portfolio management approach. Indeed, the P3O guidance recommends that an incremental approach be taken to reduce the potential adverse impacts of a big bang implementation.

Guidance on where to start with portfolio management was included in Chapter 2. As the value is proved and support grows, so a more comprehensive, end-to-end approach can be developed. This approach can be very effective – for example, one organization that has been the subject of several case studies on its approach to portfolio management is Hewlett-Packard, where the development was ‘evolutionary not revolutionary’.21 Such evolutionary approaches are particularly relevant in less stable environments and where strategy is itself emergent (i.e. in complex environments where strategy evolves as the organization learns more about ‘what works’). In such circumstances the portfolio management approach needs to reflect this in a flexible approach to implementation. However, even where this is the case, it is important to implement portfolio management as a business change programme where the desired end state is kept in mind and regular reviews are undertaken to assess progress and determine the next steps.

In other circumstances a more ad hoc approach will be adopted – this can be the case where existing practices are less mature and where senior commitment to organization-wide, end-to-end portfolio management is less well embedded. In such circumstances, a less structured approach may be the only one feasible, although it should be recognized that planned approaches, whether big bang or evolutionary, do have several advantages:

![]() Planned approaches to the implementation of business change are supported by Best Management Practice guidance.

Planned approaches to the implementation of business change are supported by Best Management Practice guidance.

![]() Experience shows that the use of structured, systematic processes drastically improves the likelihood of success.

Experience shows that the use of structured, systematic processes drastically improves the likelihood of success.

![]() A planned approach, with confirmed senior management buy-in, will significantly reduce the risk of failure. Ideally, a board-level member should fill the role of SRO for the implementation of portfolio management.

A planned approach, with confirmed senior management buy-in, will significantly reduce the risk of failure. Ideally, a board-level member should fill the role of SRO for the implementation of portfolio management.

![]() Planned approaches can be quicker, so the potential benefits are realized earlier.

Planned approaches can be quicker, so the potential benefits are realized earlier.

5.4 HOW IS PROGRESS SUSTAINED?

After an encouraging start, many implementations of portfolio management rapidly run into difficulties. Notwithstanding investments in staff, training and new software, the whole process can become bogged down in internal politics, silo-based interests and inertia. The lessons learned from those who have avoided or overcome these issues are that continued progress is assisted by incorporating the following factors:

![]() A senior-level sponsor to maintain focus at the highest level and to continually promote a portfolio-level view.

A senior-level sponsor to maintain focus at the highest level and to continually promote a portfolio-level view.

![]() An incremental or staged approach, starting with areas of greatest need to demonstrate the value of portfolio management with some ‘quick wins’.

An incremental or staged approach, starting with areas of greatest need to demonstrate the value of portfolio management with some ‘quick wins’.

![]() Building on existing organizational processes and not reinventing wheels or changing things that do not need changing.

Building on existing organizational processes and not reinventing wheels or changing things that do not need changing.

![]() Being clear about the success criteria.

Being clear about the success criteria.

![]() Regular assessment of progress – not just in terms of meeting milestones, but more significantly in relation to the benefits realized and progress against the agreed success criteria. See Appendix F.

Regular assessment of progress – not just in terms of meeting milestones, but more significantly in relation to the benefits realized and progress against the agreed success criteria. See Appendix F.

![]() Effective and ongoing stakeholder engagement and communications.

Effective and ongoing stakeholder engagement and communications.

![]() Aligning the reward and recognition processes with the appropriate behaviours (i.e. taking a corporate rather than departmental or functional perspective) – and enforcing them through objective-setting and personal reviews. This is especially important for senior management, programme managers and budget holders.

Aligning the reward and recognition processes with the appropriate behaviours (i.e. taking a corporate rather than departmental or functional perspective) – and enforcing them through objective-setting and personal reviews. This is especially important for senior management, programme managers and budget holders.

![]() Adopting a champion–challenger model where processes are open to challenge and improvement – but until successfully challenged, all agree to adhere to the current process. This helps to ensure that stakeholders are actively involved in the portfolio practices rather than perceiving them as something that is done to them.

Adopting a champion–challenger model where processes are open to challenge and improvement – but until successfully challenged, all agree to adhere to the current process. This helps to ensure that stakeholders are actively involved in the portfolio practices rather than perceiving them as something that is done to them.

![]() A commitment to continuous improvement, including identifying improvements to the portfolio management practices via membership of appropriate professional groups, capturing lessons learned from robust post-implementation reviews, submissions under the champion–challenger model and periodic portfolio effectiveness reviews (including those using a relevant maturity framework such as P3M3).

A commitment to continuous improvement, including identifying improvements to the portfolio management practices via membership of appropriate professional groups, capturing lessons learned from robust post-implementation reviews, submissions under the champion–challenger model and periodic portfolio effectiveness reviews (including those using a relevant maturity framework such as P3M3).

![]() Appropriate use of software tools tailored to support organizational needs. It was noted in Chapter 2 that software solutions are not a prerequisite for effective portfolio management although, that said, the appropriate use of tools which are tailored to the organizational requirements can help embed the new ways of working as BAU.

Appropriate use of software tools tailored to support organizational needs. It was noted in Chapter 2 that software solutions are not a prerequisite for effective portfolio management although, that said, the appropriate use of tools which are tailored to the organizational requirements can help embed the new ways of working as BAU.

Sustaining progress is also dependent on the commitment of key stakeholders (most crucially, senior management) and the existence of sufficient organizational energy.

5.5 WHY DOES ORGANIZATIONAL ENERGY LINK THE PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT CYCLES?

The concept of organizational energy, which was introduced in the last chapter, is a significant consideration in many organizations, particularly those that recognize that human capital is the most precious of all assets and those where the scale of change is increasing. The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement22 has defined organizational energy as ‘the extent to which an organization has mobilized the full available effort of its people in pursuit of its goals’. This definition is based on research in the Organizational Energy Programme at the University of St Gallen, Switzerland, and by Henley Business School, who similarly define organizational energy as ‘the extent to which an organization (or division or team) has mobilized its emotional, cognitive and behavioural potential to pursue its goals.’23

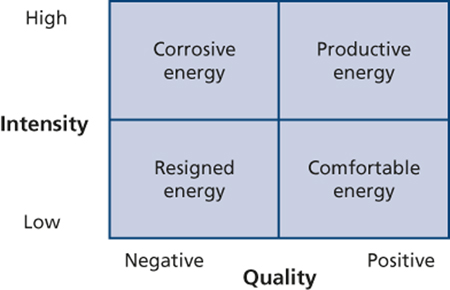

Bruch and Vogel24 identify four energy states:

![]() Productive energy People with high emotional involvement are on the lookout for new opportunities and take decisive action to solve problems because they really care about the success of the organization.

Productive energy People with high emotional involvement are on the lookout for new opportunities and take decisive action to solve problems because they really care about the success of the organization.

![]() Comfortable energy There is a relaxed atmosphere and people prefer the status quo.

Comfortable energy There is a relaxed atmosphere and people prefer the status quo.

![]() Resigned energy People are mentally withdrawn and do nothing more than is required of them.

Resigned energy People are mentally withdrawn and do nothing more than is required of them.

![]() Corrosive energy People experience high levels of anger, fight each other, and actively hinder change and innovation.

Corrosive energy People experience high levels of anger, fight each other, and actively hinder change and innovation.

When these types of energy are mapped on a matrix using the axes of ‘intensity’ and ‘quality’ as in Figure 5.1, a picture can emerge that will enable organizations to plan a route from where they are to where they want to be – with the ideal being within the ‘productive energy’ quadrant. Movement to this quadrant requires the development of a shared vision to which the portfolio contributes, clear leadership and a range of initiatives that engage staff and ignite the sources of organizational energy. These sources of energy have been identified as:25

![]() Connection – how people link themselves, their values and their work to the purpose of the organization.

Connection – how people link themselves, their values and their work to the purpose of the organization.

![]() Content – work stimulates and provides a sense of achievement.

Content – work stimulates and provides a sense of achievement.

![]() Context – working practices support and enable people to do a good job.

Context – working practices support and enable people to do a good job.

![]() Climate – how the organization helps people to grow, achieve their potential and do their best.

Climate – how the organization helps people to grow, achieve their potential and do their best.

It is critical to appreciate that whilst portfolio management will enable informed decision-making, without the collective, coordinated effort of all those involved (and management of that effort) the delivery of the portfolio and contribution to strategic objectives will be at risk. Staff engagement is considered in section 7.6.

Figure 5.1 Organizational energy matrix

5.6 PORTFOLIO DEFINITION CYCLE

5.6.1 What is the purpose?

The purpose of the portfolio definition cycle is to collate key information that will provide clarity to senior management on the collection of change initiatives which will deliver the greatest contribution to the strategic objectives, subject to consideration of risk/achievability, resource constraints and cost/affordability. The key output of the portfolio definition cycle is an understanding of what the portfolio is going to deliver – encapsulated in a portfolio strategy (the long-term view of the portfolio and its contribution to strategic objectives) and a portfolio delivery plan which focuses on the forthcoming planning period. Together, these documents will reflect the decisions taken by the management board (or sub-boards when portfolio functions are delegated) regarding the scope, contents, key milestones, costs, risks and the results anticipated from delivering the portfolio successfully.

5.6.2 What happens if this is done well?

The overriding benefit of the portfolio definition cycle is its focus on providing clarity on the high-level scope, schedule, dependencies, risks, costs (and affordability) and benefits of the potential change initiatives – which in turn enables the portfolio governance body to make informed decisions on the composition of the portfolio to optimize strategic contribution.

Defining the portfolio does not mean that everything in the portfolio must be planned in detail. Indeed, it would be wrong to attempt to do this because that is the role of programme and project management. However, a clear line of sight on the high-level milestones, estimated cost and resource requirements, risks, dependencies and benefits provides a basis for a shared understanding of the portfolio and managing progress. It also ensures that the organization matches the planned changes with its capacity to deliver without over-committing or, alternatively, having excess idle resources.

5.6.3 What if this is not done well?

If the portfolio definition cycle is not managed well, there is a high risk that the portfolio will not represent the best use of available resources in the context of the organization’s strategic objectives and aggregate risk; pet projects will consume resources at the expense of higher-priority initiatives; activities will be started without considering their fit with the current portfolio; and delivery will be impacted with too many or poorly scheduled initiatives with conflicting resource requirements and unbalanced impacts on BAU.

5.7 PORTFOLIO DELIVERY CYCLE

5.7.1 What is the purpose?

The purpose of the portfolio delivery cycle is to ensure the successful implementation of the planned change initiatives as agreed in the portfolio strategy and delivery plan, whilst also ensuring that the portfolio adapts to changes in the strategic objectives, project and programme delivery and lessons learned.

5.7.2 What happens if this is done well?

Resources, risks and dependencies will be efficiently and effectively managed, and senior management will gain greater control over the change portfolio. This in turn will enable improved delivery on time and to budget, whilst facilitating benefits realization and helping to ensure that the portfolio remains strategically aligned by enabling resource reallocation when required.

5.7.3 What if this is not done well?

Portfolio delivery is aligned to the organizational strategy, which means it will be managed over a number of years (usually three or four years, although some large organizations plan strategically for five or ten years). During that time, organizational and environmental change will occur. If the portfolio delivery cycle is not managed effectively in the context of these changes, many initiatives will not be delivered on time and to budget; demand and supply for resources will not be matched, resulting in shortages and idle capacity; inadequate action will be taken to address poor performance and slippage; initiative scheduling will result in unnecessary operational disruption; the portfolio will not adjust to shifts in business priorities and consequently money will be spent unwisely; and the contribution to strategic objectives will not be optimized.