2 Principles

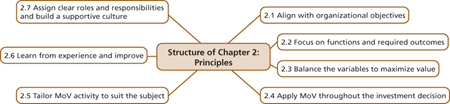

Figure 2.1 Structure of Chapter 2

This chapter explores the seven fundamental principles underpinning MoV:

![]() Align with organizational objectives

Align with organizational objectives

![]() Focus on functions and required outcomes

Focus on functions and required outcomes

![]() Balance the variables to maximize value

Balance the variables to maximize value

![]() Apply throughout the investment decision

Apply throughout the investment decision

![]() Tailor to suit the subject

Tailor to suit the subject

![]() Learn from experience and improve

Learn from experience and improve

![]() Assign clear roles and responsibilities and build a supportive culture.

Assign clear roles and responsibilities and build a supportive culture.

For MoV to be effective, it is essential to apply the principles introduced above and described in more detail below. If these principles are not followed, MoV is not being properly used. The principles have evolved over the past fifty years through successful practice across many sectors of industry and commerce.

They are intended to provide clear and concise guidance to senior management and users alike. They are not intended to be prescriptive but to provide a clear framework for individuals and organizations to evolve their own policies, processes and plans to suit their particular needs.

2.1 ALIGN WITH ORGANIZATIONAL OBJECTIVES

Principle

MoV activities must be aligned with the organization’s objectives or portfolio strategy to ensure a consistent and contributory approach across all programmes and projects.

The first principle of MoV is that organizational activities must all align with an organization’s objectives. In the same way that every project within a programme is designed to contribute to achieving the objective of the programme, so every activity to maximize value must be similarly linked. Without such coordination, there is a risk that maximizing value within one project in isolation could diminish value across the wider programme.

Programmes are put together in order to fulfil the organization’s objectives or portfolio strategy. Each project within the programme is designed to contribute directly or indirectly to achieving the programme outcomes. The objectives of each project should also be complementary to the other projects within the programme, ideally without overlap. Every product or element within each project should contribute to the project objectives. MoV activities must be aligned to maximizing value throughout this hierarchy.

Example

An organization was consolidating its activities from more than 50 sites, each with diverse operations and different standards of accommodation, to just five locations. One of the strategic objectives was to harmonize the way people worked across the whole business.

In a series of MoV activities covering the entire programme, a programme-level value profile was established. This allowed the team to align each project’s value profile with that at programme level from the outset.

Using these, it was possible to ensure that the five consolidated operational centres were consistent, despite pressures from individual operators for different standards. Success was measured by the fact that all units adopted the same working methods and enjoyed consistent standards of accommodation.

2.2 FOCUS ON FUNCTIONS AND REQUIRED OUTCOMES

Principle

MoV focuses on what things do to contribute to the required outcomes before seeking to improve them. This approach clarifies expectations and stimulates innovation.

MoV focuses on defining what programmes and projects must achieve before seeking ways in which value may be delivered or enhanced. This ensures that the right questions are asked before leaping to preconceived solutions. For example, many buildings have been commissioned to increase available space or production, when what was really needed was a rationalization of current practice to make better use of what was already there or an innovative approach to obviate the need for the facility at all.

Example

A local authority was proposing to lease a nearby building in order to accommodate additional staff and facilities. An analysis of the functions performed by the various departments allowed the operational activities to be streamlined, reducing the need for additional staff and enabling them to share some facilities. The resultant rationalization obviated the need for additional space.

2.2.1 Functions

Functions describe what things must do, rather than what they are. Looking at functions provides the key to understanding programmes and projects and how they might be improved.

Functions do not simply apply to physical products but also to abstract concepts. For example, the function of a door handle may be to open a door; the function of a work of art may be to stimulate the senses; the function of a piece of software may be to enable an operator to work efficiently. Functions are normally expressed using an active verb and a measurable noun, sometimes qualified by an adjective or other descriptor.

At a different level the function of a programme is to deliver one or more strands of portfolio strategy. The function of a project is to deliver one or more requirements of a programme (assuming it is part of a programme, which is not always the case).

Functions may be arranged in a hierarchy to express their relationship to the programme or project objectives. Those that relate directly to the programme or project objectives are termed primary functions, whilst those that relate to other functions are classified as secondary, tertiary and so on.

The functional approach is central to articulating essential requirements in unambiguous terms that all those who are involved in the programme or project can understand. It is also one of the keys to stimulating innovation.

2.2.2 Value drivers

‘Value driver’ is another term for a primary function and expresses how to create value for the organization in line with its objectives. Even abstract requirements like ‘proximity to public transport’ may be expressed as functions such as ‘enable easy access to public transport’. Value drivers are necessary since they are directly related to the programme or project objectives and, in aggregate, are sufficient to achieve the project’s objectives in full. Value drivers differentiate one organization’s or project’s priorities from another’s. They are used to judge the success of a project where they are delivered in full. They are one of the keys to measuring improvements in value.

Clarity in describing value drivers is crucial, since these will differentiate one project from another of a similar type.

Example

A budget hotel and a luxury hotel will have some common value drivers, but the descriptions of the primary and/or secondary value drivers will differentiate the quality and performance standards required. For example, some budget hotels will not serve meals, whilst luxury hotels invariably will.

2.2.3 Function diagrams

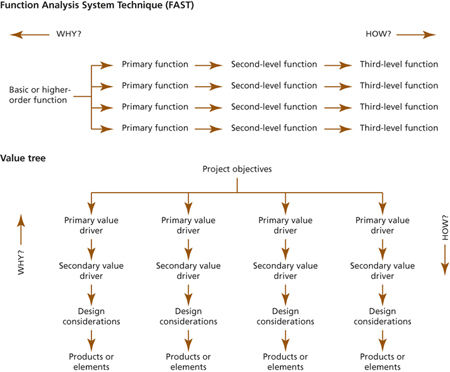

A function diagram provides a means of relating primary functions or value drivers to the overall programme or project objectives in a logical sequence by asking ‘How?’ and ‘Why?’ The diagram provides a simple method of defining essential programme or project requirements. There are two commonly used types of function diagram, the Functional Analysis Systems Technique (FAST) and the value tree, as indicated in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 The principles of function diagrams

Abstraction is a term that indicates how far a function is removed from the products or elements that make up the completed project. Primary functions or value drivers represent the highest levels of abstraction. The products or elements represent the lowest. Asking the question ‘Why?’ increases the level of abstraction, while asking the question ‘How?’ lowers the level of abstraction.

2.2.4 Value profile

Whilst all value drivers are important and must be delivered in full to yield a successful outcome, some will be more critical than others to achieving the organization’s success. This reflection of criticality is indicated by weighting the relative importance of each value driver. To provide a true reflection of the requirements for success, value drivers should be independent of each other. Assessment of weightings should also be tested for robustness against the risks of inaccuracies in estimation.

The weighted value tree is known as a value profile, since it articulates in clear terms the key functions that drive value and their relative importance.

The relative importance of different value drivers provides a good insight into priorities at organizational, programme and project levels.

Example

‘Ensure fastest delivery’ might be the critical value driver for one logistics operation, because the speed of service might be the critical factor that differentiates that firm from its competition or perhaps the goods deteriorate rapidly in transit. Another organization may place greater emphasis on reliability and identify ‘Ensure goods arrive in perfect condition’ as its critical value driver.

2.3 BALANCE THE VARIABLES TO MAXIMIZE VALUE

Principle

MoV balances the variables to maximize value, taking account of and reconciling the views of all key stakeholders, the use of resources and the overall ratio of benefits to expenditure.

There are three main areas where it is necessary to strike a balance in order to maximize value. These are:

![]() Reconciling the needs and views of different stakeholders to maximize overall benefits by brokering a consensus on their differing expectations to deliver what they need.

Reconciling the needs and views of different stakeholders to maximize overall benefits by brokering a consensus on their differing expectations to deliver what they need.

![]() Balancing the use of resources to reflect their availability and the organization’s priorities by redistributing across the different value drivers to reflect their relative importance.

Balancing the use of resources to reflect their availability and the organization’s priorities by redistributing across the different value drivers to reflect their relative importance.

![]() Balancing the overall benefits realized with the use of resources by optimizing the value for money ratio.

Balancing the overall benefits realized with the use of resources by optimizing the value for money ratio.

This balancing process is discussed in section 3.6.3 and is illustrated in the modified value ratio diagram in Figure 3.4.

Value is subjective and different stakeholders will have different expectations and priorities. These differences need to be reconciled to achieve a balanced outcome that achieves willing consensus between the different stakeholders. The value profile provides a means of achieving such consensus.

MoV is all about maximizing value in line with the programme and project objectives and the key stakeholder requirements. It is not simply about minimizing costs. Nor is it about delivering or even maximizing the benefits (at any cost). It is a question of balancing the variables to maximize value. Value may sometimes be maximized by eliminating a service or cancelling a project.

The formal processes and techniques that should be used are described in Chapters 3 and 4. These should be conducted rigorously, regardless of project size, whilst the level of effort should be scaled as appropriate to the size and complexity of the challenge.

2.3.1 Engagement of stakeholders

Achieving the optimum balance described above requires that the views of all key stakeholders, both internally and externally, are taken into account and reconciled.

Stakeholders are those that can affect or be affected by (or perceive themselves to be affected by) the project or programme. They may be internal or external to the organization that is applying MoV or to the project to which MoV is being applied. Typically they may be end users or customers, the local community, relevant third-sector organizations, other government entities – anyone impacted by the study. The extent to which different stakeholders’ views will be taken into account will depend upon their influence on achieving the required beneficial outcome of the project.

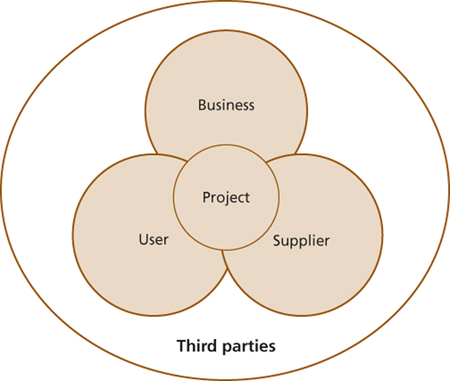

PRINCE2 groups stakeholders in a project under three main headings: business, user and suppliers. These include external stakeholders. Mindful of the environment within which a project is being undertaken, MoV emphasizes the need to encompass third parties who have an interest in the project (and those who may have influence over it). To achieve the optimum balances described in the previous section, it will be necessary to engage with all four groups of stakeholders and reconcile their different views on the variables (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Programme or project stakeholders

2.3.2 Reducing subjectivity

Value is subjective in that different people will place a higher value on some benefits than others. This particularly applies to those benefits that cannot be translated into cash terms, for example aesthetics or the ease with which management can take decisions. This subjectivity is particularly apparent when considering non-financial issues but is also present in issues with financial implications.

Example

A railway company wanted to undertake a feasibility study for the re-invigoration of a substantial part of its network. MoV was used to test the appropriateness of the brief.

The end users were interested in performance issues such as reliability, maintainability and adaptability, whereas internal stakeholders were predominantly focused on the financial aspects of the business case.

The outcome of the study was a significant re-drafting of the feasibility study brief to include the end users’ views. Success was demonstrated by the buy-in to the revised feasibility remit and the resolution by the company to conduct similar consultation exercises on all future major projects.

2.3.3 Balancing the use of resources

The value profile provides the key to trading off the use of different resources to optimize value. This includes all resources used in the delivery of the benefits, not only costs, and should include such items as time, people, materials and energy. Elapsed time in delivering a project is a resource. However, time can also be a value driver; for example, time to market may be a dominant value driver. In such cases, increased expenditure on materials and people may reduce the time to market. Articulating such trade-offs and achieving the optimum balance are critical to maximizing value.

Examples

Time to market is critical in many fields.

For example, in the oil industry the sooner production can be brought on stream, the sooner revenue will start to flow. The additional revenue from early production is likely to far outweigh the additional costs of accelerating the installation of the production facility. Similarly, launching a new toy in time for Christmas is critical to its success.

2.3.4 Balancing benefits realized against use of resources

The greater the benefits delivered and the fewer resources that are used in doing so, the higher the value ratio. Whether benefits are increased or decreased, or whether the use of resources is increased or decreased, the challenge lies in achieving the optimum balance in the prevailing circumstances, i.e. the balance which leads to the highest value ratio. The ideal situation, of course, is where it is possible to increase benefits delivered and reduce resources used. By contrast, it is possible to increase value using increased resources, provided the increase in value is greater than the increase in resources.

Example

By spending more on training staff and improving the environment in a hospital, patients may recover more quickly and need to spend less time as inpatients. The benefits of improved capacity to treat patients may outweigh the additional cost of training and improving the environment.

There is also the additional benefit that patients will appreciate the speedier recovery and release.

2.4 APPLY MOV THROUGHOUT THE INVESTMENT DECISION

Principle

MoV should be planned and applied throughout all stages of a programme or project to reflect the evolving requirements in order to maximize value.

Throughout the lifecycle of an investment decision, the focus of effort under MoV evolves to reflect requirements of the stage reached. Those engaged in MoV activities should be selected because they have the skills and experience that are relevant at the current stage in the evolution of the project, thus enabling them to contribute effectively to MoV activities. In all programmes and projects, formal MoV studies should be undertaken at all key decision points to inform the decision-making process. The scale of the study should be matched to the issues to be addressed.

At project start up, information on which to base decisions is generally limited to that contained in the project brief and the outline business case. If the project is part of a wider programme, much of the information will derive from the programme vision and blueprint. When starting up a project, MoV clarifies the information that is available to assist in the development of a more comprehensive business case.

At later stages, MoV builds on the information generated to assist in making decisions; for example, the selection of options, based on value, informs the project and design briefs and provides a mechanism to enhance the benefits whilst reducing or making better use of resources.

MoV contributes to achieving positive reviews under the OGC Gateway Review process, for example by demonstrating that the project definition has been tested by the project team and clearly articulated at OGC Gateway 3, where the investment decision is taken.

Example

A critical constitutional project was allocated a red status at the OGC Gateway 2 Review. Application of MoV enabled the team to achieve a green status at a second review by addressing the weaknesses identified during the OGC Gateway Review. It also clarified the design brief. Subsequent MoV studies contributed to the project being delivered on time and to budget.

Once a project is completed, MoV can be used to improve operational performance.

Some programmes or projects, once completed, may lead to opportunities to improve operational performance. In other circumstances the programme or project itself may be about improving operations. In either case MoV may be used to increase operational efficiency, as well as its economy and effectiveness.

2.5 TAILOR MOV ACTIVITY TO SUIT THE SUBJECT

Principle

The scope and scale of MoV activity should be tailored to reflect the size, complexity and strategic importance of the programme or project.

From its inception in the 1940s to current practice, MoV has evolved from narrow, product-based applications to those informing the vision and objectives of programmes and projects in all sectors. In the same way, organizations should adapt and amend their MoV policies and practices to learn from experience and enhance effectiveness.

To avoid wasting resources, MoV should be adjusted to suit the scale and complexity of the subject project. Different projects will require different levels of MoV activity. At programme or project start up, it is advisable for the programme or project management to categorize projects in terms of their size, novelty, complexity and strategic importance. There is no point in taking a sledgehammer to crack a nut when a lighter touch will suffice. Likewise it is essential that care is taken to ensure the tools and techniques selected are appropriate for the circumstances.

A large and complex project may require that MoV is applied to different parts of the project throughout all project stages. A small and simple project will not require the same level of effort, and one or two formal studies throughout its life may suffice. Formal studies should be considered at all key decision points.

Where there are many small projects that are repeated time and time again, for example in the upgrading of a chain of shops, it may be worth spending more effort to maximize value on one project, since the benefits will be magnified by the number of projects.

Example

A retail company was embarking on a programme of refurbishment to refresh its brand. Several MoV studies were conducted on typical outlets to optimize the design. Although the effort expended would have been hard to justify against the small number of stores that were studied, the benefits of scale across hundreds of similar stores repaid the effort many times over, due to reduced implementation time and costs and enhanced sales.

Regardless of the scale of MoV activity, care must be taken to ensure the MoV principles are applied.

The level of MoV effort that is appropriate for the project and how it will be integrated with other project management activities should be ascertained by the project executive/manager and the MoV study leader at the outset, and a project MoV plan established. This should be incorporated within the overall end-to-end project schedule so that the whole project team knows when formal or informal MoV studies will take place and what their objectives will be.

2.6 LEARN FROM EXPERIENCE AND IMPROVE

Principle

MoV performance should be continually improved by learning from previous experience.

When embarking on introducing and embedding MoV into an organization, or using MoV on a standalone programme or project, it will take time to build up proficiency. However, benefits can still be achieved even with limited experience. Undertaking MoV studies will help organizations to focus their scarce resources better on what matters to their customers, but will not necessarily improve proficiency in MoV across the organization.

It is one of the principles of MoV, in common with most management activities, that an organization should put in place a process for continuous learning from experience, using this to improve performance. Programme or project start up provides a critical time to take up lessons learned from previous experience, to avoid repetition of past mistakes and to build on things that delivered success.

Continuous learning should address three areas:

![]() Individual performance where individuals improve their ability to undertake MoV studies. This will come about through learning from their own experience, training, learning from other people’s experience and increasing familiarity and confidence in applying the processes in different circumstances.

Individual performance where individuals improve their ability to undertake MoV studies. This will come about through learning from their own experience, training, learning from other people’s experience and increasing familiarity and confidence in applying the processes in different circumstances.

![]() Improvement in the quality of delivery of MoV processes. These should evolve by refining the MoV processes to match the requirements of the organization and the type of applications within it.

Improvement in the quality of delivery of MoV processes. These should evolve by refining the MoV processes to match the requirements of the organization and the type of applications within it.

![]() Improving the organization’s overall maturity in MoV.

Improving the organization’s overall maturity in MoV.

Continuous improvement will be greatly assisted through the development and use of a lessons-learned database, allowing access to all involved in MoV.

2.6.1 Individual improvement

Improvement of individuals’ MoV competence will be achieved through three main activities:

![]() Building upon their initial MoV training received to increase their knowledge of MoV processes and case studies.

Building upon their initial MoV training received to increase their knowledge of MoV processes and case studies.

![]() Gaining experience in undertaking their MoV roles and responsibilities (whether by managing MoV activities or process delivery).

Gaining experience in undertaking their MoV roles and responsibilities (whether by managing MoV activities or process delivery).

![]() Seeking to improve their professional competence as indicated in Appendix D.

Seeking to improve their professional competence as indicated in Appendix D.

As individuals become more proficient, so they will be able to contribute directly to improving the evolution and application of MoV processes to the specific needs of the organization.

2.6.2 Process improvement

The MoV processes and techniques, described in Chapters 3 and 4, should be regarded as the starting point in customizing practice in an organization. Every organization has its own distinctive culture and way of doing things. The challenges faced by each organization and the applications of MoV will vary depending upon the organization’s business.

2.6.3 Organizational maturity improvement

A realistic plan should be prepared to elevate the organization’s MoV practices to the next level in the maturity model, if appropriate. Prior to implementing this plan, the benefits accruing from reaching the next level of maturity should be compared with the costs to be incurred by doing so. If progression is then recommended within a robust business case, it should be managed as a project in its own right, with clear objectives, resources and timeframe. The concept of improving maturity is explained in Appendix D.

2.7 ASSIGN CLEAR ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES AND BUILD A SUPPORTIVE CULTURE

Principle

MoV should be actively supported by senior management, clear roles and responsibilities, and a supportive culture throughout the organization.

Organizations that have sufficient demand for MoV to warrant building up their own internal delivery capability should ensure that there is adequate governance in place to support and deliver it. The process of introducing MoV to an organization and embedding it to the point that it becomes part of the way the organization does business is described in Chapter 7. It will be noted that it is not proposed that MoV requires a separate tier of management, rather that the roles and responsibilities of existing individuals relating to portfolio, programme and project management should be extended to include responsibilities for MoV.

Part of the role of the senior MoV practitioner, the person responsible for managing the MoV effort, will be to undertake activities and publish material to build a culture within the organization that understands and supports the concept of maximizing value both for the organization and the project stakeholders.

When applying MoV within the portfolio of programmes or projects, it is essential that individual roles and responsibilities are clearly defined to enable good communications with the teams involved at all levels.

Even if an organization is applying MoV on a project-by-project basis, it should ensure that MoV activity is actively supported and managed if the full benefits are to be realized.