3 Processes

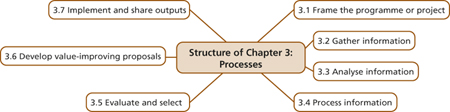

This chapter describes the MoV processes that may be applied throughout the lifecycle of a project (see Figure 3.1). It also describes how MoV may be applied across a programme of projects, in IT and in non-project environments such as the delivery of services.

Figure 3.1 Structure of Chapter 3

MoV activities change as a project evolves from inception, or start up, to use (business as usual) in line with the issues to be addressed, so that outputs at each stage support the project’s progress. Some processes will be used at many stages, others only in specific stages.

The most common techniques that are suggested for use in the MoV processes are described in Chapter 4. Other techniques that are not specific to MoV are outlined in Appendix B.

3.1 FRAME THE PROGRAMME OR PROJECT

This describes how MoV can assist management to validate or challenge the need for a programme or project and define what is needed.

3.1.1 Initial briefing meeting

As soon as a project has been identified for the application of MoV, the senior MoV practitioner, or study leader if identified, should meet with key project stakeholders to establish the requirements for the MoV project plan (see section 3.1.5).

3.1.2 Informing the business case

The main objective of an MoV study at the outset, or start up, of a programme or potential project is to strengthen existing information so that senior management can make an informed decision as to whether or not to authorize initiation. This enables efficient development of a robust business case. An MoV study at this stage may be used to inform an OGC Gateway 0 or 1 Review.

The content of a business case is normally as follows:

![]() A summary The reasons for the project: a statement of the existing situation, or combination of situations, giving rise to the need for change. MoV can be used to challenge this statement and to find ways either to justify it or to re-state it such that alternative solutions can be found.

A summary The reasons for the project: a statement of the existing situation, or combination of situations, giving rise to the need for change. MoV can be used to challenge this statement and to find ways either to justify it or to re-state it such that alternative solutions can be found.

![]() The expected benefits, dis-benefits, timescales and costs These should be included in the statement of project objectives and should be given clearly and explicitly, focusing on the outcome to be achieved rather than proposed solutions. MoV will use the techniques for identifying and prioritizing value drivers, detailed in Chapter 4, to ensure that the objectives selected are those that reflect the requirements of the programme (if the project is part of a programme) or business needs, and that they have the potential to add most value.

The expected benefits, dis-benefits, timescales and costs These should be included in the statement of project objectives and should be given clearly and explicitly, focusing on the outcome to be achieved rather than proposed solutions. MoV will use the techniques for identifying and prioritizing value drivers, detailed in Chapter 4, to ensure that the objectives selected are those that reflect the requirements of the programme (if the project is part of a programme) or business needs, and that they have the potential to add most value.

![]() The options The case should explore several options (one being to do nothing) and recommend one for implementation. Options should be set out with estimates of their costs and benefits to demonstrate the rationale for the recommendation. MoV’s emphasis on using value drivers as selection criteria will favour the option that adds most value in context, taking costs and benefits into account. At this stage the option not to undertake the project might be demonstrated to be the most advantageous.

The options The case should explore several options (one being to do nothing) and recommend one for implementation. Options should be set out with estimates of their costs and benefits to demonstrate the rationale for the recommendation. MoV’s emphasis on using value drivers as selection criteria will favour the option that adds most value in context, taking costs and benefits into account. At this stage the option not to undertake the project might be demonstrated to be the most advantageous.

![]() The risks The business case should include assessment of risks. By exploring alternatives and providing information to improve decision-making, MoV’s value-improving proposals reduce uncertainty and avoid the potential destruction of value.

The risks The business case should include assessment of risks. By exploring alternatives and providing information to improve decision-making, MoV’s value-improving proposals reduce uncertainty and avoid the potential destruction of value.

![]() The investment appraisal MoV can improve the viability of a project by maximizing the benefits whilst reducing the use of resources, including costs.

The investment appraisal MoV can improve the viability of a project by maximizing the benefits whilst reducing the use of resources, including costs.

![]() Procurement strategy The method of procuring a project can make a significant difference to its value. The business case should explore several options and recommend a reasoned procurement strategy. MoV can be used to inform the selection of the preferred strategy.

Procurement strategy The method of procuring a project can make a significant difference to its value. The business case should explore several options and recommend a reasoned procurement strategy. MoV can be used to inform the selection of the preferred strategy.

3.1.3 Stakeholder analysis

Stakeholder analysis is a complex subject. In MoV, stakeholder mapping is used to ensure that the appropriate stakeholders are consulted or involved in the MoV processes. Stakeholders are grouped according to their degree of influence (or power), the interest they have in the project and whether they support it or not. This provides a means of prioritizing the stakeholders who need to be consulted in an MoV study.

Whilst all stakeholders should be involved as far as possible, it is reasonable to focus on building an active relationship with those who have the power to block or facilitate delivery. Stakeholders with less power but great interest can form strong allies; they can help to influence those who are more powerful and encourage others who are less interested not to become detractors.

Example

A group of councillors was vigorously opposing the relocation of a school to new premises. Analysis of the root causes behind their objections uncovered the fact that they were not opposed to the re-siting of the school so much as the fact that they lived next to the existing school and feared that the redevelopment of the site would devalue their homes.

Once this was understood, the negotiations focused on reassuring the councillors that the redevelopment would not have the impact that they feared, resulting in them withdrawing their objections.

3.1.4 Use of a value profile to inform programme and project objectives

An essential part of the business case is the statement of project objectives. There is no point in starting a project unless there is agreement on its purpose. MoV helps to identify the primary value drivers and relate them to the project objectives using a weighted value tree.

This technique, known as value profiling, provides a useful method of testing that the requirements of project sponsors and end users are aligned, thus verifying that this is the right project for the business.

Example

A hospital pharmacy was exploring a project to make significant cash savings from its budget. MoV helped the department to recognize that the pharmacy’s function was not so much ‘dispensing drugs’ as ‘managing medication’. This was relevant to the whole hospital, not only the pharmacy. Whereas the pharmacy cost around £2 m per year to run, it influenced broader hospital costs of around £19 m.

The resulting value-improving proposals included shorter average patient stay, less potential litigation and savings in nursing time. The cost savings amounted to one year’s total cost of the pharmacy department for the hospital, far greater than had been expected from the original project proposal.

3.1.5 Developing the MoV project plan

The main purpose of the MoV project plan is to describe the purpose of a series of MoV studies to be undertaken throughout the project and how they will be implemented. It will identify suitable candidates to lead and participate in the studies, ensure sufficient training resource at the appropriate time and prepare specific management responses to value-improving proposals. With thorough preparation, the risk of delay in authorizing the implementation of these proposals should be minimized, thus ensuring that MoV is more sustainable within the organization.

The plan does not need to be a long document but should include:

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Outline of the issue to be studied

Outline of the issue to be studied

![]() Statement of business objectives (the intended outcome)

Statement of business objectives (the intended outcome)

![]() Roles and responsibilities

Roles and responsibilities

![]() Specification of suitable candidates for the study team

Specification of suitable candidates for the study team

![]() Training needs for qualifying candidates

Training needs for qualifying candidates

![]() Specific management responses to team proposals, e.g. who will make a particular decision and how long this should take (this should include authorization levels)

Specific management responses to team proposals, e.g. who will make a particular decision and how long this should take (this should include authorization levels)

![]() Process(es) to be followed, key decision points, deliverables and activities

Process(es) to be followed, key decision points, deliverables and activities

![]() Nature and timing of the studies

Nature and timing of the studies

![]() Tools and techniques to be used

Tools and techniques to be used

![]() Reporting

Reporting

![]() Quality reviews and controls

Quality reviews and controls

![]() Glossary of terms.

Glossary of terms.

The use of the plan ensures that all participants understand the need for each study and what improvement is sought. The project sponsor may have specific demands that will shape the way in which the study is run.

3.1.6 Responding to changes in the business case

If the business case changes, for example in response to changes in market conditions, the MoV project plan must also change in order to ensure that the value profile reflects the changed needs of the business. This will have an impact on the selection of options or the development of value-improving proposals. It may be necessary, therefore, to repeat processes that have already been undertaken to reflect the changes.

Agile project management demands that the business case be revisited in the light of what is learned with each release of a product.

3.1.7 Specialist applications

In some circumstances the OGC Gateway model of controlling projects may not be appropriate, for example in some IT projects or the application of MoV to service delivery. In these circumstances some of the guidelines given in this document may not apply.

It is in the nature of IT projects that what stakeholders think they need changes as soon as they have an opportunity to use a working version of the product. Most projects allow for this by testing early models or prototypes before the design is fixed, but in some cases it is possible to continue to adjust the design until close to delivery. Many software and new product development projects incorporate this feature, which requires an iterative lifecycle and modified MoV techniques to take full advantage of the opportunities to maximize value.

This more flexible approach does not obviate the need to define clearly what stakeholders are trying to achieve – their value drivers. It does, however, require a willingness to adjust initial hypotheses in the light of new information, and it makes it imperative that goals are expressed in terms of desired outcomes and not outputs.

Properly executed, this process will reduce risk (because value-added solutions are facilitated through trial and error) and expense because many unnecessary features can be eliminated before development costs mount up. Repeated value analysis is used to select and prioritize potential features for development and the output of each iteration is reviewed in operation with end users to test their response to the changes and elicit fresh understanding of their needs.

Whilst project MoV studies are usually very clear on expected outcomes and who is responsible for their delivery, this is not always the case with service delivery studies. Since improvements in value will often be greatest outside the department originating the study, a great deal of stakeholder influence is needed to ensure benefits are fairly shared. Therefore, it is not unusual to involve additional stakeholders partway through the study as it becomes clear that they will be affected by a proposed service improvement.

Operational reviews may be conducted at organizational or operational levels and can vary significantly in scale according to their objectives. A public-sector cross-cutting policy can affect hundreds of staff (and, in turn, many thousand service users or customers) and may require several months of effort. On the other hand, internal studies may be quite small, be of much shorter duration and affect fewer people.

3.2 GATHER INFORMATION

As a first step during any MoV study, information must be gathered to compile the MoV study handbook. This is a short document for the benefit of all contributors, describing the key attributes of the proposed study. Some of the key processes are outlined here.

The MoV study handbook should be proportionate to the size of the study and the familiarity of participants with MoV. For a simple study with informed participants, the handbook may comprise a few sheets summarizing the planned activities. For a more complex study, it may need to be much more detailed and cover all the aspects contained in this chapter.

3.2.1 Briefing meeting

At the outset of a proposed study, at programme or project level, the study leader should convene and chair a briefing meeting focused purely on study issues. This comprises a meeting with the key project stakeholders, including the project senior responsible owner (SRO) or project executive, the end users, the project manager and other key identified stakeholders, to establish study objectives, scope and other information needed to conduct the study. In some cases more than one meeting may be required to cover the complete agenda (see Appendix A) with all relevant parties and to select the MoV study team (see section 3.2.2).

The briefing meeting gives the study leader all that is necessary to gather and analyse the information required for development of an MoV study handbook, which acts as a briefing document for those in the study team. This should include roles and responsibilities for all contributors.

3.2.2 Team selection

Team members are generally selected for their skills, abilities and capacity for interacting successfully with other team members.

The MoV team members will be nominated by the project’s management team, with input from some key stakeholders. Ideally, a team should be drawn up on the basis of team members’ knowledge of the issues to be addressed and their characteristics and skills in providing a solution.

At the outset of introducing MoV in an organization, it may be difficult to choose the most suitable study leaders (several will be needed, depending on the number of concurrent MoV studies anticipated). Over time the better study leaders and contributors will be identified and a preferred pool accumulated. They should be appropriately recognized and rewarded.

Similar considerations apply when selecting teams for individual studies. Usually these are made up of those who are involved in the project, with little choice available. The study team should include key members from the project team to include all critical disciplines and, where appropriate, external advisers. It is good practice to consider involving experienced people who are not otherwise involved in the project to bring greater objectivity to the study proceedings. This could also be achieved by a peer review.

In constructing the MoV study team, all key disciplines included in the project delivery team should also be represented. This ensures that when the MoV study team refines designs and project execution plans, all views have been taken into account. The stakeholders, who may or may not be involved in the MoV study, also need to have confidence that their views will be adequately represented in the delivery process as well as being included in the development of the MoV study handbook. They should therefore be consulted as discussed at sections 3.1.3 and 3.2.3.

There is a substantial weight of literature on team dynamics and personality profiling, which can be useful for building high-performance teams, to which the reader is referred in Appendix B.

Operational or service delivery studies may involve large numbers of stakeholders. In these circumstances, because it can be impractical to gather all stakeholders together, MoV studies may comprise many consultations with small groups in preference to larger workshops.

MoV works best when all participants work collaboratively together. If the participants have not worked together before, it may be necessary to conduct team-building exercises. A team can be defined as ‘a group working together to achieve a common goal’. Team-building, therefore, is aimed at helping these individuals do this more effectively. Team-building is the subject of many management books and articles, some of which are referred to in Appendix B.

Example

In a wide-ranging review of a local authority’s children’s services it became clear that traditional methods were not engaging the right people in the change process. By analysing the service functions from a customer perspective it became clear that the various service agencies could cooperate in a cross-cutting partnership to make significant improvements in children’s services. The MoV processes brought together the elected councillors and a wide range of other stakeholders and ensured a shorter and sharper review process.

3.2.3 Consulting with stakeholders

Although the stakeholders in a project may sometimes be obvious, this is not always the case. Steps should therefore be taken to ensure that all the key stakeholders have been identified; techniques for doing this are described in MSP.

The study leader should consider engaging with the following groups, to a greater or lesser extent, in any MoV study:

![]() The sponsors/owners of the project

The sponsors/owners of the project

![]() Representatives of key customers or customer groups

Representatives of key customers or customer groups

![]() The organization(s) providing funds for the project

The organization(s) providing funds for the project

![]() The project team, including project manager, commercial managers, design disciplines and, if appropriate, contractors

The project team, including project manager, commercial managers, design disciplines and, if appropriate, contractors

![]() Specialist advisers and/or objective ‘off-project’ experts

Specialist advisers and/or objective ‘off-project’ experts

![]() Staff and/or potential end users or typical representatives

Staff and/or potential end users or typical representatives

![]() Representatives of the external community who may be affected by the project.

Representatives of the external community who may be affected by the project.

Not all aspects of a project will be of interest to all stakeholders. For example, the cost of a project or the way in which the completed project will be operated may be of little interest to the community where it is located. However, people in the area may well take a great interest in how it impacts on their day-to-day lives. If their views are not considered as the details of the project evolve, they may be in a position to disrupt its execution or operation. If their money has been used to fund the project (e.g. through taxes), they may perceive it as poor value unless their views are reflected.

All major stakeholders for the project need to be identified and engaged. They should be provided with timely, specific and clear information regarding proposals and their impacts throughout the development process. Regular feedback on progress is necessary to manage their expectations so that unrealistic objectives are avoided.

In the early stages of a project, it is vital to gain the support of senior management and influential external stakeholders to arrive at the optimal project brief and select the most appropriate options. Capturing, discussing, aligning and agreeing the main objectives are essential actions. Failure to identify and involve all major stakeholders during the identification of objectives stage may lead to overall project weakness or an outright failure to deliver.

Throughout, it will be necessary to understand and communicate effectively with external stakeholders who may be in a position to exert influence over the project. Techniques for engaging with stakeholders are available through many sources including MSP and PRINCE2 – for example, stakeholder profiles and stakeholder mapping. In particular, MSP has copious detail on stakeholder management, and MoV would use these processes in preference to creating its own. Every effort should be made to ensure that each MoV study includes the stakeholders that matter.

Example

The generation of the development strategy for a multi-billion-dollar new town development in the Middle East involved a large number of stakeholders from different organizations. The MoV study leaders interviewed people in small groups or individually to minimize the disruption to their daily work. After analysing their findings, they presented their proposals to a small group of key decision makers for agreement before finalizing their recommendations.

3.2.4 Research and precedent

It is good practice to start a project by examining how the same or similar issues have been treated previously. The information for such precedents will be captured in MoV reports and be entered into the lessons-learned database. Initially, before an organization has built up its own database, study leaders and participants will need to access published data and material on appropriate websites. Analysing how others have managed similar issues can save a lot of time. Benchmarking against similar projects can provide useful data for establishing the performance levels of the project under study, informing the setting of objectives and targets and focusing studies on areas of apparent underperformance.

3.2.5 Scoping

At the briefing meeting, it is important to establish whether the study is to address the whole project or only part of it. If only part, then which part or parts? The distinction between constraints (which may be challenged and are therefore within the scope of the MoV study) and givens (which are excluded from discussion) should also be identified clearly.

3.3 ANALYSE INFORMATION

3.3.1 Function analysis

Function analysis is a key component of MoV, one which differentiates it from other management methods, including PRINCE2 which focuses on product-based planning. Function analysis seeks to gain clarity of what a thing does, rather than what it is.

All products have one or more basic functions. For example, a hotel must accommodate residents; it must also receive visitors and enable guests to check out; it may feed residents, although some hotels do not provide dining facilities; it may facilitate exercise through gym facilities and encourage leisure activities such as golf. These latter functions are supporting functions that differentiate one hotel from another.

Function analysis opens the door to three fundamental changes in mindset:

![]() Until the purpose of something is defined, it is not possible to assign a value to it. For example, a brick has little or no value until it is put to use. As a door stop, its value is very low; as a part of a decorative façade, it may have considerable value.

Until the purpose of something is defined, it is not possible to assign a value to it. For example, a brick has little or no value until it is put to use. As a door stop, its value is very low; as a part of a decorative façade, it may have considerable value.

![]() Understanding what things do provides greater insight into the overall purpose and required performance of elements within a project, leading to a better understanding of the project itself.

Understanding what things do provides greater insight into the overall purpose and required performance of elements within a project, leading to a better understanding of the project itself.

![]() Asking the question ‘How else could we perform the function of this part of the project?’ stimulates the generation of innovative alternatives that may perform better at less cost, rather than simply seeking different versions of the same part.

Asking the question ‘How else could we perform the function of this part of the project?’ stimulates the generation of innovative alternatives that may perform better at less cost, rather than simply seeking different versions of the same part.

Function analysis is described in more detail in Chapter 4.

3.3.2 Resource analysis

To maximize value, it is essential that the MoV team has a good understanding of the resources used in delivering the benefits.

3.3.2.1 Cost estimation

There are many methods for estimating capital and whole-life costs, different methods being used in different sectors.

The construction industry uses methods such as the Building Cost Information Service (BCIS) under which total installed costs of an element are estimated against precedent and market trends. The estimates include allowances for waste, poor performance and risk. Care should therefore be taken to avoid ‘double counting’. The estimates are usually market-tested to refine the expected out-turn costs of a project.

Engineering works often calculate costs of equipment and installation separately to arrive at total installed costs.

Operating and running costs are built up from known labour costs, estimated labour requirements and data from similar operations. Obtaining these costs can involve significant research. Estimating future cash flows relies on forecasting trends, which can be a very inexact science. The accuracy of cash flows using these estimates will have a significant impact on calculating whole-life costs or net present values and should always be treated with caution.

Commonly, an initial model is tabled and successively refined as more data becomes available. This applies particularly when calculating costs on IT and change projects, as these also suffer from uncertainties of scope. It is recommended that the study team agrees during the selection process what level of confidence is adequate to support a decision, so that the project can move on quickly.

There are several techniques for presenting the information that has been gathered in ways which will aid understanding of the key drivers of cost, time and use of materials.

3.3.2.2 Cost modelling

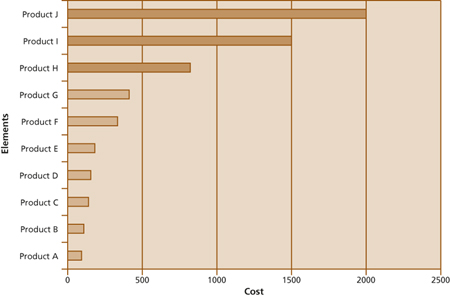

Presenting costs in graphical format (see Figure 3.2) can make it much easier for the non-expert to understand the causes of the major costs and their magnitude. There are a great many cost-modelling techniques, for which signposts may be found in Appendix B.

Figure 3.2 Example of a cost distribution histogram

3.3.2.3 Time analysis

Most projects should have a logic-linked, end-to-end schedule (see Figure 3.3), typically prepared using computer software. This can be used to prepare simple graphical formats that clearly indicate the key maturity models and decision points in a project. Sometimes a simple schedule of key dates is sufficient to enable team understanding.

Figure 3.3 Example of an end-to-end project schedule

3.3.2.4 Material analysis

Where a project involves the use of materials, the use of graphical images, such as material usage histograms, can provide insights into the potential pinch points in a schedule; similarly, statistics on waste can stimulate proposals for its reduction. The same technique may be used for avoiding overloading human resources.

Example

The main objective of an MoV study into a complex scientific research building was to determine the most effective building sequence to minimize the impact of construction traffic on surrounding roads. The MoV team used resource-linked schedules to prepare traffic histograms to help determine the optimum schedule.

Pareto’s law (the 80:20 rule) can help teams to focus on the areas of the project in which there is the greatest potential to enhance value. If, for example, cost reduction is one of the study objectives, there is a greater likelihood that 80% savings will be found in areas of high cost (the top 20% of expenditure) than where costs are low.

3.3.3 Function cost analysis

The ability to estimate the costs of value drivers (or functions), in conjunction with their relative importance, enables the MoV team to assess whether a particular value driver or function represents good value for money. Whilst delivering value drivers or primary functions is essential to achieving the project objectives, this should not be done at any cost.

This process also enables the team to redistribute the use of resources (generally represented by costs) from one area of a project, which might represent poor value, to another where similar expenditure will deliver greater benefit, thus enhancing value overall.

Example

A proposed new food production facility was running over budget and did not incorporate several features required by its owners. The MoV team drew up a detailed function diagram, prioritized the value drivers and analysed the costs for delivering each function. By identifying opportunities for making significant cost reductions in the areas of low priority, enough money was saved to fund the incorporation of the missing features as well as bring the designs back within budget.

Generally, costs that are presented in activity-based cost format are easier to convert to function-based costs than those that relate to products.

3.3.4 Benchmark analysis

Comparing the analysis of information for one project against other similar projects can be very revealing and highlight areas where value improvements could be made. This process is known as benchmarking and can cover all aspects of performance and resource.

Whilst any external comparison will be very informative, benchmarking exclusively with same-type organizations can mask opportunities for innovation. Benchmarking against a wider pool of other industries whose only common feature lies in the type of process being compared can furnish some startling results.

Example

A public-transport firm benchmarked many aspects of its operation with other similar organizations to refine its operational efficiency and safety procedures. An MoV study proposed that it should compare certain aspects of its operation with different types of business, including a theme park and an aviation company. This novel approach led to some significant process changes, enabling headcount reduction whilst at the same time improving safety standards.

When conducting an MoV study to improve operational efficiency or service delivery, it is essential to understand existing performance levels to use as a baseline for measuring proposed improvements.

3.4 PROCESS INFORMATION

At the heart of an MoV study is the need to process the information that has been gathered and analysed, using the processes described above, to develop value-improving proposals. Invariably, the study leader will work closely with the MoV team members to do this.

The most common, efficient and effective way to process the information is by means of one or more structured workshops, facilitated by the study leader and attended by all the MoV team members.

Sometimes, convening a workshop is neither desirable nor practical. In such cases the study leader will consult with the MoV team members individually or in small groups to achieve results. In these cases it will be necessary to build consensus between the different parties to avoid disagreements later in the project.

Whichever method is used, controlling the activity requires all the skills described in selecting suitable study leaders, together with the knowledge acquired from this guide and elsewhere. This section provides guidance for exercising good control over the process.

3.4.1 Preparation

3.4.1.1 MoV study handbook

This document should be prepared by the study leader, based on information gained in the briefing meeting. It should be distributed to the MoV team before the workshop or consultation commences. It collates all the information gathered, with such analyses as have already been conducted, so that the study team can work from an informed base.

3.4.1.2 Invitation

To ensure that all participants know in advance the venue, timing, purpose and agenda for the workshop or consultation, the study leader should distribute an invitation to each participant in good time beforehand. A suitable outline is provided in Appendix A.

3.4.2 Facilitation

Effective leadership of an MoV study requires comprehensive and specific knowledge of MoV (contained in this guide) and facilitation skills. In common with many activities, particularly those requiring people skills, practice makes perfect. Novice facilitators should be provided with as many opportunities as possible to develop these skills. This may be accomplished by encouraging them to act as assistant study leaders initially to build up their confidence and to hone their sharpness.

As a facilitator, the study leader is someone with the skills to orchestrate a workshop or other meeting such that full contribution can be made by every member. The facilitator’s focus is on the process, rather than the contributions themselves. Facilitation skills may be acquired through training and will include the following:

![]() Presentational skills and the ability to command a group of experienced and often senior professionals.

Presentational skills and the ability to command a group of experienced and often senior professionals.

![]() The ability to conduct group processes, including being able to decide when it is best to use a group and when best to work individually.

The ability to conduct group processes, including being able to decide when it is best to use a group and when best to work individually.

![]() The ability to know the difference between a group and a team and to motivate a group to work as a team. Some time will need to be allocated to introductions and forming relationships where teams have not worked together before.

The ability to know the difference between a group and a team and to motivate a group to work as a team. Some time will need to be allocated to introductions and forming relationships where teams have not worked together before.

![]() A sound understanding of workshop dynamics, allowing team members to focus on their contributions. The study leader will state the purpose of the workshop, set the ground rules and keep the workshop on track. This may mean dealing with difficult people and conflict. Study leaders need to develop intuition for events that require their intervention.

A sound understanding of workshop dynamics, allowing team members to focus on their contributions. The study leader will state the purpose of the workshop, set the ground rules and keep the workshop on track. This may mean dealing with difficult people and conflict. Study leaders need to develop intuition for events that require their intervention.

![]() Capturing information generated during a study. The study leader also needs to record the proceedings and gather information during the study. It is often helpful in workshops for the study leader to engage a scribe, so that all data can be recorded and managed in plain sight of the team. Alternatively, they can be assisted by a data recorder or a co-facilitator where the circumstances support it.

Capturing information generated during a study. The study leader also needs to record the proceedings and gather information during the study. It is often helpful in workshops for the study leader to engage a scribe, so that all data can be recorded and managed in plain sight of the team. Alternatively, they can be assisted by a data recorder or a co-facilitator where the circumstances support it.

![]() Handling conflict. Conflict is not necessarily bad – indeed, it can be very constructive, as long as it is resolved effectively. Selecting team members from diverse backgrounds and disciplines heightens the chances of a high-quality solution, but inevitably it also increases the chances of disagreement. Conflict can often reveal problems of which the study leader and even the team were not aware. Turned to good effect, this can lead to a solution and enhance everyone’s understanding of the issues. However, conflict handled badly can destroy teamwork and lead to disengagement.

Handling conflict. Conflict is not necessarily bad – indeed, it can be very constructive, as long as it is resolved effectively. Selecting team members from diverse backgrounds and disciplines heightens the chances of a high-quality solution, but inevitably it also increases the chances of disagreement. Conflict can often reveal problems of which the study leader and even the team were not aware. Turned to good effect, this can lead to a solution and enhance everyone’s understanding of the issues. However, conflict handled badly can destroy teamwork and lead to disengagement.

![]() Understanding the causes of conflict. Conflicts may arise from scepticism about the process, the presence of difficult individuals, or hidden or competing agendas. The study leader needs to acknowledge that an issue exists and move the focus off those presenting it, so that it can be discussed impartially. Therefore:

Understanding the causes of conflict. Conflicts may arise from scepticism about the process, the presence of difficult individuals, or hidden or competing agendas. The study leader needs to acknowledge that an issue exists and move the focus off those presenting it, so that it can be discussed impartially. Therefore:

![]() Let individuals express their feelings, as this will make it easier to manage their emotions separately.

Let individuals express their feelings, as this will make it easier to manage their emotions separately.

![]() Define the problem and its impacts and then determine the underlying need. It isn’t a question of determining who is right or wrong but of trying to reach a solution that works.

Define the problem and its impacts and then determine the underlying need. It isn’t a question of determining who is right or wrong but of trying to reach a solution that works.

![]() Focus on why people have such strong feelings and the points they have in common, no matter how small. This might be a way to bring two sides together.

Focus on why people have such strong feelings and the points they have in common, no matter how small. This might be a way to bring two sides together.

![]() As much as possible, encourage objectivity.

As much as possible, encourage objectivity.

![]() It may be necessary to consider what will happen if the conflict cannot be resolved. There are several models of conflict styles and how to manage them, which are signposted in Appendix B.

It may be necessary to consider what will happen if the conflict cannot be resolved. There are several models of conflict styles and how to manage them, which are signposted in Appendix B.

![]() Generating team ownership and buy-in. It is vital that all MoV team members are kept fully involved in the workshop and consultation so that they feel that they have had every opportunity to contribute and participate in the selection and development of proposals. This involvement should continue throughout the study, including the opportunity to present proposals to senior management. Personal ownership in the proposals will greatly enhance the chances of their acceptance and implementation.

Generating team ownership and buy-in. It is vital that all MoV team members are kept fully involved in the workshop and consultation so that they feel that they have had every opportunity to contribute and participate in the selection and development of proposals. This involvement should continue throughout the study, including the opportunity to present proposals to senior management. Personal ownership in the proposals will greatly enhance the chances of their acceptance and implementation.

3.4.2.1 Dealing with difficult people

The presence of difficult people can be a cause of conflict. It certainly undermines efficiency. Some points to consider are:

![]() Behaviours are sometimes driven by a desire to get the job done. This isn’t necessarily bad, though the way it is expressed may need management.

Behaviours are sometimes driven by a desire to get the job done. This isn’t necessarily bad, though the way it is expressed may need management.

![]() Understand the effects of this behaviour, good and bad, and the personalities that manifest as a result.

Understand the effects of this behaviour, good and bad, and the personalities that manifest as a result.

![]() Sometimes, the behaviour of another is what triggers adverse behaviour. Consider the effect your own actions may have.

Sometimes, the behaviour of another is what triggers adverse behaviour. Consider the effect your own actions may have.

![]() Whilst most people invited to participate in meetings or workshops are collaborative and constructive, there are those who can be difficult to control. The following are some of the more common examples encountered, together with suggested means of handling them:

Whilst most people invited to participate in meetings or workshops are collaborative and constructive, there are those who can be difficult to control. The following are some of the more common examples encountered, together with suggested means of handling them:

![]() Those who will not contribute even when you know they have plenty to offer – invite them to participate, without threatening them; play to their egos by flattering them.

Those who will not contribute even when you know they have plenty to offer – invite them to participate, without threatening them; play to their egos by flattering them.

![]() Those who like to dominate the proceedings – limit time for discussions or deliberately invite others into the discussion.

Those who like to dominate the proceedings – limit time for discussions or deliberately invite others into the discussion.

![]() The expert who uses jargon which no one else understands, or who gives too much detail – don’t be afraid to ask what a particular piece of jargon means. Often others in the meeting won’t know either or will have a different interpretation. Ask for a short summary of what was just said so that you can record it.

The expert who uses jargon which no one else understands, or who gives too much detail – don’t be afraid to ask what a particular piece of jargon means. Often others in the meeting won’t know either or will have a different interpretation. Ask for a short summary of what was just said so that you can record it.

![]() Those who insist that theirs is the only solution that will work – getting others to contribute credible alternatives and solutions that have been successful elsewhere in similar circumstances, or working out a way to allow this person to leave with dignity are two ways to avoid stifling the innovation of others.

Those who insist that theirs is the only solution that will work – getting others to contribute credible alternatives and solutions that have been successful elsewhere in similar circumstances, or working out a way to allow this person to leave with dignity are two ways to avoid stifling the innovation of others.

![]() When a new process is introduced in an organization it will take time for people to understand and become proficient in its use. MoV is no exception, and this may be the reason for some initial resistance to its use. The problem may be resolved by being patient or providing some additional training or mentoring to those involved.

When a new process is introduced in an organization it will take time for people to understand and become proficient in its use. MoV is no exception, and this may be the reason for some initial resistance to its use. The problem may be resolved by being patient or providing some additional training or mentoring to those involved.

3.4.3 Creativity and innovation

Function analysis provides an opportunity to assess which functions offer the most scope for value-adding change, leading to great creativity.

Two key questions that may be asked at this stage are:

![]() Why are we doing it and what are the alternatives?

Why are we doing it and what are the alternatives?

![]() How can it be done differently and/or better?

How can it be done differently and/or better?

The former question may reveal that the function is unnecessary, leading to the elimination of a product or part of a process.

Consideration of alternative ways to perform a function provides greater scope for innovation than considering alternatives for a product. Frequently it can lead to the elimination of an element altogether.

Example

One of the primary functions of a door is to enable access. Access may also be enabled by providing a zig-zag entrance comprising two overlapping walls. This eliminates the need for a door, facilitates better access and reduces initial and maintenance costs.

There are many methods of generating ideas for solutions, and a selection is offered in Appendix B. These include brainstorming, which is probably the most commonly used technique for generating a large number of creative ideas. The study leader should visibly record every idea, regardless of its merits, for future consideration (see section 4.4.2.1).

In order to generate the largest number of creative ideas, the study leader should firmly disallow any attempt to discuss the merits or demerits of each idea during the creative session. Such discussion will inhibit the generation of ideas and waste time. A good session may generate several hundred ideas and the greater the number of ideas, the greater the number of acceptable innovations.

In IT projects, development methods also need innovative approaches, particularly where iteration is desirable. Other methods, such as agile approaches, which can support completion of time-boxed iterative processes, have been developed in response to this requirement.

3.5 EVALUATE AND SELECT

Having generated a large number of ideas and suppressed their evaluation during the creative session above, it is necessary to allow people to exercise their judgement to select suggestions that have greatest potential to enhance value. There may also be a number of ways to progress the project that need assessment on their merits in order to select the most advantageous.

Under MoV, evaluation of proposed solutions is generally undertaken by assessing their performance against the value drivers. This ensures that selection is based on grounds that add most value to the project.

3.5.1 Idea selection

There are several techniques for selecting the most promising ideas from a large number generated during a creative session. Each involves the MoV team, not the study leader, in applying their judgement based on their technical and project knowledge.

Essentially, the ideas are assessed for how well they satisfy the functions as well as the study objectives. Assessment against the study objectives may be made using several relevant criteria, for example:

![]() Reduces capital cost

Reduces capital cost

![]() Speeds up delivery

Speeds up delivery

![]() Enhances productivity.

Enhances productivity.

Alternatively, the team may prefer to use criteria that are related to the implementation of the ideas, such as:

![]() Acceptability

Acceptability

![]() Relative ease of achievement

Relative ease of achievement

![]() Cost of delivery

Cost of delivery

![]() Scale of the improvement.

Scale of the improvement.

All assessments are recorded, as some might be useful to other projects, even if not for the one under study. The best ideas are assigned to an owner, called a proposal owner, for further development later during the workshop or by an agreed date. Where time is short, it is common for owners to develop ideas into value-improving proposals outside the workshop; this allows them to work individually or with colleagues (who may not have been present during the workshop) to refine their proposals.

If time permits, or when it would be difficult to reconvene the team, developing the value-improving proposals in the presence of the whole team can be very effective, as an energetic atmosphere develops, enhancing productivity. If the proposals are complex, it may still be necessary to validate the proposals developed during the workshop before they are submitted for consideration by senior project management.

Where the value-improving proposals are developed or validated outside the workshop, the group of specialists charged with developing the proposals will need a clear brief and timetable to report their findings.

3.5.2 Option selection

MoV studies may be used to select options at two levels:

![]() At project start up or project initiation, the business case requires presentation of several options as referred to in section 3.1.2 above.

At project start up or project initiation, the business case requires presentation of several options as referred to in section 3.1.2 above.

![]() During the delivery stages (which include design), various options regarding how to deliver certain aspects of the project may be identified.

During the delivery stages (which include design), various options regarding how to deliver certain aspects of the project may be identified.

Techniques for selecting options in each of these cases are presented in Chapter 4.

Example

An engineering firm was bidding to develop an offshore oil and gas facility. The brief from the owner of the field was simple: ‘Maximize the value of the recoverable assets.’ The engineers had identified ten potential options for developing the field.

A subsequent MoV study tested the options against eight value drivers and concluded that option number seven would best fulfil the objective described in the brief. The team then went on to identify ways of improving the selected option in terms of reliability and performance, reduced installation costs and time, and innovative thinking in order to differentiate themselves from the average bidder.

3.5.3 Cost benefit analysis

In the same way as costs of delivering benefits may be estimated by analysing the use of resources, it is necessary to estimate the value of benefits that are delivered.

Whilst many benefits have direct financial impacts, many do not. MoV provides unique techniques for assessing the non-monetary benefits, such as value-profiling and assessing the value for money ratio. These are presented in Chapter 4.

These techniques complement conventional cost benefit analysis.

3.6 DEVELOP VALUE-IMPROVING PROPOSALS

A key output from an MoV study is the acceptance of value-improving proposals for implementation into the project under study.

The proposal owner (see section 3.5.1 above) works up a detailed proposal, with costs and gains tested for sensitivity. A proposal summary document outline is offered in Appendix A. The study leader will need to liaise with project management to ensure that sufficient resource is available and allocated to the task.

Where two or more proposals compete, it will be necessary to develop scenarios combining different options to identify the package that adds most value (see section 3.6.8). The proposal owners must also take note of other proposals being worked up that might lead to conflicting recommendations being presented to senior management.

The study leader should convene and chair a decision-building meeting at which proposal or scenario owners present their ideas to a panel of senior managers. The purpose of this meeting is to discuss the findings of each proposal and agree whether or not it should be implemented in whole or in part.

The decisions are recorded and form the basis of a proposal implementation plan. This plan provides the project managers with details of proposals, how and when they will be implemented and the expected value improvements (or benefits). This allows them to monitor and manage the implementation process.

3.6.1 Proposal development formats

It is good practice to have all proposals summarized in a standard form for consistency (rather than as random forms of presentation, which may be difficult to compare).

The checklist offered in Appendix A provides a useful summary that can be used when presenting proposals to the decision-making panel, since it contains a summary of all the key information that panel members need to make a decision.

3.6.2 Peer review

This can be an excellent method of gaining feedback on strengths and weaknesses of the subject under study, allowing for constructive challenge and recommended solutions to be made.

3.6.3 Balancing the benefits and use of resources

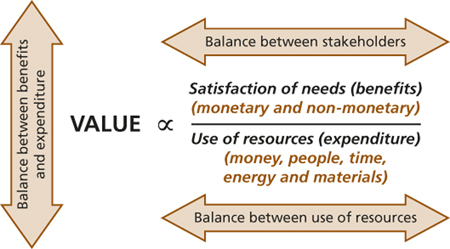

One of the principles of MoV, introduced in section 2.3, is the need to ‘balance the variables to maximize value’ (see Figure 3.4). This should be done whilst developing value-improving proposals and so is described in a little more detail here.

There are three main areas where it is necessary to strike a balance:

![]() Balancing the benefits and expenditure on resources used

Balancing the benefits and expenditure on resources used

![]() Balancing the benefits between stakeholders

Balancing the benefits between stakeholders

![]() Balancing the use of resources.

Balancing the use of resources.

Figure 3.4 Balancing the variables to maximize value

3.6.3.1 Satisfaction of needs (benefits) vs use of resources (expenditure)

The first of these is the balance between satisfaction of needs (benefits) and resources used (expenditure), as illustrated by the value ratio in Figure 3.4. The greater the benefits delivered and the fewer resources that are used in doing so, the higher the value ratio. Whether benefits are increased or decreased, or whether the expenditure is increased or decreased, provides a challenge to achieve the optimum balance in the prevailing circumstances, i.e. that which leads to the highest value ratio. For example if, by spending more on training, patients are cured quicker and need to spend less time in hospital, the benefit of improved capacity to treat patients may well outweigh the additional cost. There is also the additional benefit that patients will appreciate speedier recovery. The ideal situation, of course, is where it is possible to increase benefits delivered and reduce expenditure.

3.6.3.2 Satisfaction of needs

Second, value is subjective in that different people will place a higher value on some benefits than others. This particularly applies to those benefits that cannot be translated into cash terms, for example aesthetics. Many construction projects are likely to include a value driver such as ‘communicate the brand’ (referring to how the building will look). Tastes vary between individuals – one group of stakeholders may prefer one image whilst another will prefer something quite different. If both groups have an active interest in the project outputs, their views must be reconciled in the selected design to maximize value overall.

3.6.3.3 Use of resources

The third area of balance concerns the use of resources. The value profile provides the key to trading off the use of different resources to optimize value. These include all resources used in the delivery of the benefits, not only costs, and include such items as time. One organization or group of stakeholders, for example, may wish to spend more in order to reduce the time taken to deliver the benefits. Another may wish to reduce spending to a minimum since speed of delivery is not critical. Articulating such trade-offs and achieving the optimum balance are critical to maximizing value.

3.6.4 Value metrics

The value profile together with the use of scenarios provides a method of assessing improvements in value to the project overall, based upon monetary and non-monetary benefits. Quantifying value using value metrics is discussed in detail in section 4.1.2.5.

3.6.5 Cost estimation

When selecting value-improving proposals for implementation, it is not normally necessary to have completely accurate cost estimates for either the benefits or implementation costs to make a decision as to whether or not to implement. It is more important to achieve consensus between the study team members on the approximate costs for these items.

3.6.6 Assessing time impact

It can be difficult to estimate how long it will take to implement a proposal. A professional scheduler will have experience in estimating the duration and resource requirements of all the activities needed to implement a proposal and will be able to superimpose these, together with how they are linked and their dependencies, into the overall project schedule. Even if implementing a proposal takes some time, if it is not on the critical path it may not delay the project. Conversely, saving time on one proposal may not reduce the overall schedule because it may not be on the critical path. The schedule should include time for project management, for other discipline processes, for human elements such as holidays and sickness, as well as an approximation of the potential costs of any delay, whether incurred through interest, opportunity cost or value forgone. These extra factors may significantly increase the original estimate.

3.6.7 Assessing performance impact

Performance may be assessed by many methods, including monitoring benefits realized, throughput or outputs per employee, achievement of key performance indicators or financial results. Technical subjects may require assessments of improved reliability, operational costs and impact on the natural environment. Performance improvements may also be assessed using the MoV techniques of value profiling and value metrics referred to earlier in this section.

3.6.8 Scenario building

Several value-improving proposals may be gathered into one or more scenarios, allowing the team to present a comprehensive package of activities that will provide the greatest improvement in value.

3.6.9 Specialist applications

In evolutionary iterative IT projects, MoV continues during development and becomes an integral part of each cycle. The prioritization and selection process begins when the products of each iteration are tested on customers and stakeholders so that progress towards targets can be evaluated and priorities adjusted.

3.7 IMPLEMENT AND SHARE OUTPUTS

The agreed proposal implementation plan should be filed together with the MoV study report for later comparison with results delivered. The plan will provide useful information in the lessons-learned database.

3.7.1 Developing the proposal implementation plan

A single MoV study is capable of generating a number of robust proposals. As part of the presentation of the proposals to the decision makers, an implementation plan should be drawn up.

A proposal implementation plan can be short – simply a statement of which measures are to be monitored and the scale of the benefit expected over a defined period of time. In many cases it will be an extension of the summary of all the proposals being put forward for discussion.

The plan should include:

![]() A list of the recommended value-improving proposals and the proposal owners for each

A list of the recommended value-improving proposals and the proposal owners for each

![]() A short description of how they will be included into the project

A short description of how they will be included into the project

![]() The timescale for their inclusion, giving the scale of benefits expected over time

The timescale for their inclusion, giving the scale of benefits expected over time

![]() Dates and method for monitoring and reporting progress

Dates and method for monitoring and reporting progress

![]() A mechanism for review should progress fall below expectations.

A mechanism for review should progress fall below expectations.

Once authority to proceed with implementing all or some of the proposals has been achieved, the plan should be amended to reflect any agreed changes.

Winning commitment to change from those affected will be critical, especially if the proposal involves potentially controversial changes such as a reduction in budget or head count.

3.7.2 Incentivizing delivery of value

Unless there is a desire amongst those involved in MoV to improve value, it is unlikely to deliver its full potential. Staff may be motivated by MoV making the value they have added visible to them and/or linking this to rewards. Rewards need not be monetary but can be related to building pride in success.

Example

On an affordable housing project in Scotland, an innovation that was introduced following an MoV study was the ‘save a tenner scheme’. Under this scheme workers were encouraged to identify ways to save £10 in costs per week by rewarding them with £10 per week for between 1 and 4 weeks. They could take the reward in any way they chose – the most cost-effective for them being to leave work early on a Friday, having completed their tasks, and be paid in full. The scheme proved very popular and resulted in significant savings for the employer as well as an incentivized and happy workforce.

3.7.3 Monitoring progress

The expected benefits resulting from the implementation of a proposal will be stated in the implementation plan.

Wherever possible, the measures for adding value should be the same as those that are already being used in the project.

Some projects may employ a process known as benefits management. This is described in detail in the MSP guide and provides a rigorous process for identifying, modelling, mapping and monitoring the delivery of the benefits expected from a programme or project. It does not, however, provide a ready means of maximizing benefits.

If such a process is being effectively employed, it may be appropriate to feed the value-improving proposals arising from MoV studies into the process.

The benefits map under the above process relates ‘strategic objectives’ and ‘project outputs’ in a similar way to the value profile. There may, therefore, be a way to integrate the two processes using the value profile.

If such a process is not being actively used, the realization of the additional benefits identified under the MoV process should be monitored either by the study leaders involved or by the project management team. The normal way to do this is to include an MoV progress report in the regular project reports, setting out the current status of the benefits realized.

3.7.3.1 Earned value analysis

Earned value analysis (EVA) is a project control tool that can be useful in monitoring progress. Essentially, it provides a method of monitoring costs incurred against progress and comparing these with what was planned. If costs incurred exceed those that were predicted at the time of review, it indicates that the budget may be exceeded.

3.7.4 Reporting

The study leader must prepare a report after every study to provide a record of the study and set out the proposal implementation plan.

3.7.4.1 Study output reports

Each MoV study will conclude with a separate report, describing the context and purpose of the study, the selected processes, the outputs and/or recommendations. Suitable document checklists are given in Appendix A. It is good practice to divide reports into two sections. The first provides a summary of the outputs, for the benefit of senior management. The second contains all the details needed for the project team to implement the proposals. The detailed reports will be made to the project director/manager and a summary sent to the senior MoV practitioner and/or sponsor.

It is common practice to issue reports in draft initially and finalize them after receipt of comments from the MoV team and the project manager. The finalized reports, including the implementation plans, should be disseminated to the project team to enable implementation of the recommendations.

3.7.4.2 MoV progress reports

Summary progress reports showing implementation progress should be included in the regular project management reports, so that the delivery of the benefits may be monitored and, if necessary, action taken to overcome any difficulties.

A summary of these progress reports should be made by the senior MoV practitioner to the sponsor and possibly to other senior management to inform them of progress in implementing MoV on programmes and projects. These reports may contain recommendations based on the outputs from the activities described above for refining MoV in the organization and are key to getting continued buy-in to the MoV programme.

MoV progress reports at project or programme level form a key input to embedding MoV in the organization.