U.S. Federal Government Risk Management Initiatives

The U.S. federal government has taken many steps to help companies manage IT risks. The initiatives covered in this section are:

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

- Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

- National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC)

- United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT)

- MITRE Corporation and the CVE list

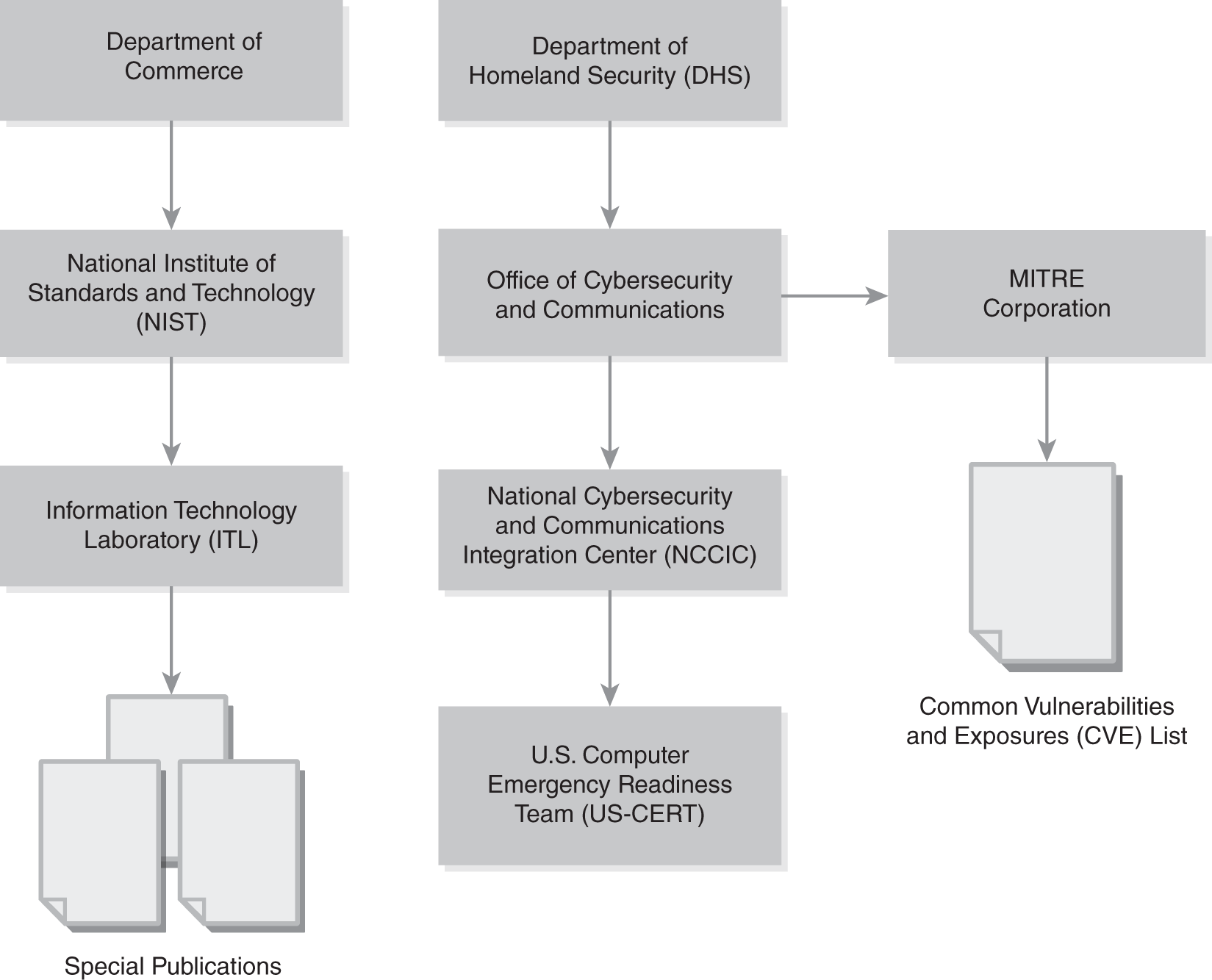

FIGURE 2-3 shows the relationships among many of these organizations. There are two primary paths, under the U.S. Department of Commerce or the DHS.

FIGURE 2-3 Relationships among organizations involved in the U.S. federal government risk management initiatives.

NIST is directly under the Department of Commerce. The Information Technology Laboratory (ITL), which is part of NIST, issues special publications. The DHS includes the Office of Cybersecurity and Communications.

Within the Office of Cybersecurity and Communications is the NCCIC. The Office of Cybersecurity and Communications provides funding for the civilian MITRE Corporation. MITRE maintains the CVE list. The US-CERT is located within the NCCIC.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is a division of the U.S. Department of Commerce. NIST’s mission is to promote U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness. It does this by advancing measurement science, standards, and technology.

NIST includes the ITL, which develops standards and guidelines. The goal is improved security and privacy of information on computer systems.

The Special Publication 800 (SP 800) series includes several reports that document ITL’s work. It includes research, guidance, and outreach efforts in computer security and is intended to be a collaborative effort combining the work of industry, government, and academic organizations. Many of the publications in the SP 800 series are available on the Internet. NIST has revised many of these documents, so the number might not reflect the relative date of the current version.

NOTE

NOTE

ITL and ITIL are two different programs. The Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) was developed by the United Kingdom (UK). It is managed by the UK Office of Government Commerce (OGC). ITIL is a collection of books that provide guidance and best practices for the successful operation of IT. The ITL, managed by NIST, is a U.S. program.

The following list includes some of these publications:

- SP 800-183, Networks of ‘Things’

- SP 800-154, Guide to Data-Centric System Threat Modeling

- SP 800-153, Guidelines for Securing Wireless Local Area Networks (WLANs)

- SP 800-150, Guide to Cyber Threat Information Sharing

- SP 800-124 Rev. 1, Guidelines for Managing the Security of Mobile Devices in the Enterprise

- SP 800-123, Guide to General Server Security

- SP 800-122, Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII)

- SP 800-121 Rev. 2, Guide to Bluetooth Security

- SP 800-119, Guidelines for the Secure Deployment of IPv6

- SP 800-115, Technical Guide to Information Security Testing and Assessment

- SP 800-100, Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers

- SP 800-94, Guide to Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (IDPS)

- SP 800-84, Guide to Test, Training, and Exercise Programs for IT Plans and Capabilities

- SP 800-83 Rev. 1, Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling for Desktops and Laptops

- SP 800-63-3, Digital Identity Guidelines (suite of documents)

- SP 800-61 Rev. 2, Computer Security Incident Handling Guide

- SP 800-55 Rev. 1, Performance Measurement Guide for Information Security

- SP 800-53 Rev. 4, Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations

- SP 800-51 Rev. 1, Guide to Using Vulnerability Naming Schemes

- SP 800-50, Building an Information Technology Security Awareness and Training Program

- SP 800-40 Rev. 3, Guide to Enterprise Patch Management Technologies

- SP 800-34 Rev. 1, Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems

- SP 800-37 Rev. 2, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy

- SP 800-30 Rev. 1, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments

- SP 800-12 Rev. 1, An Introduction to Information Security

NOTE

NOTE

The full list of Special Publications can be accessed, including links to all of them, from the NIST website at https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/sp800.

Department of Homeland Security

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is responsible for protecting the United States from threats and emergencies, including terrorist attacks. DHS is also responsible for responding to natural disasters, such as hurricanes and earthquakes.

Congress passed the Homeland Security Act of 2002 in November 2002, in which the DHS was established. Both the Homeland Security Act of 2002 and the DHS were created in response to the terrorist bombings of September 11, 2001.

The DHS includes many agencies. Some of them are:

- U.S. Secret Service

- U.S. Coast Guard

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

- Federal Emergency Management Agency

National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center

The National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC) operates within the DHS. It works together with private, public, and international parties to secure cyberspace and America’s cyberassets.

Previously, cybersecurity was scattered in different departments. Today, the NCCIC serves as the central point of contact. The NCCIC oversees several programs:

- National Cyber Awareness System—This is an email alert system that allows a person to subscribe to various emails.

- United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) Operations—This division is tasked with analyzing and reducing cyberthreats and vulnerabilities. As issues become known, US-CERT disseminates information and coordinates incident response activities. See the following section for more information about US-CERT.

- Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT)—This group works to reduce risks to critical infrastructure sectors. Such infrastructures include roads, water, communications, energy, and more.

NOTE

NOTE

One of the great benefits of the National Cyber Awareness System is that its emails don’t include advertisements. Also, because they are from the U.S. government, the information is not slanted to sell or promote specific products.

U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team

The United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) is a part of the NCCIC. US-CERT’s primary mission is to provide response support and defense against cyberattacks. Its focus is on providing support for the federal civil executive branch of government, which includes all sites with a .gov domain name. However, US-CERT also collaborates and shares information with several other entities, including:

- State and local governments

- International partners

- Other federal agencies

- Other public and private sectors

NOTE

NOTE

Cyber generally refers to any computer assets but usually refers to assets on the Internet. The global network of computers on the Internet is commonly referred to as cyberspace. Cyberwarfare, or cyberwar, refers to the attacks and counterattacks carried out against countries or companies by other countries or companies.

Information gathered by US-CERT is shared with the public through the National Cyber Awareness System. This system includes a website, mailing lists, and Really Simple Syndication (RSS) channels.

A person can sign up to receive emails and alerts from US-CERT from this link: http://www.us-cert.gov/mailing-lists-and-feeds/. A person can also sign up for the following feeds:

- Alerts—These alerts include timely information about current security issues, vulnerabilities, and exploits and are released as needed. They are written for system administrators and experienced users. Past alerts can be viewed at http://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/alerts.

- Bulletins—These bulletins provide weekly summaries of security issues and vulnerabilities from the previous week. They are written for system administrators and experienced users. Past bulletins can be viewed at http://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/bulletins.

- Current activity—These emails provide information about high-impact types of security activity. Depending on current threats, they can be sent several times a day or several times a week. Past updates can be viewed at http://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/current-activity/.

- Tips—These tips are targeted to home, corporate, and new users. They are published every two weeks and provide information on many security topics. Past security tips can be viewed at http://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/tips.

The MITRE Corporation and the CVE List

The MITRE Corporation manages four Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs). The FFRDCs conduct research for several major departments of the U.S. government.

The MITRE Corporation maintains the CVE list. MITRE is the editor of the list and is responsible for assigning numbers. The DHS sponsors the CVE.

The CVE is an extensive list of known vulnerabilities and exposures. As new discoveries are made, they are submitted as candidates for the list. The primary benefit of the list is standardized naming and descriptions.

Before the CVE existed, one company may have addressed a problem as Exploit234a. The same problem could have been addressed by another company as X42A. Both companies may have published papers regarding the same problem, but determining whether one problem was different from the other was difficult.

The CVE provides one name for any single vulnerability or exposure. The format is CVE-yyyy-nnnnnn, where yyyy is the year the vulnerability was added to the list and nnnnnn is a unique number for the year. Effective January 1, 2014, the number was expanded to six digits. Previously, only four digits were allowed, limiting the number of vulnerabilities to 9,999 CVE IDs. With six digits, MITRE can assign up to 99,999 CVE IDs. The entries include a brief description of the vulnerability and one or more references users can access for more information about the vulnerability. The following example shows a CVE entry from 2018:

- Name—CVE-2018-1999046

- Description—An exposure of sensitive information vulnerability exists in Jenkins 2.137 and earlier, 2.121.2, and earlier in Computer.java that allows attackers with Overall/Read permission to access the connection log for any agent.

- References—URL: https://www.cvedetails.com/cve/CVE-2018-1999046/

NOTE

NOTE

MITRE is an acronym, but the initials are not relevant. Many of the original employees came from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). These employees work on research and engineering (RE). However, MITRE is not a part of MIT.

NIST uses the CVE names and descriptions in the National Vulnerability Database (NVD). The NVD listings include the same information as in the CVE, but impact and severity scores are added. The page at http://cve.mitre.org/cve/ includes links to search for the entry on MITRE’s CVE list or on NIST’s NVD list.

The CVE is considered the standard for information security vulnerability names. MITRE launched the CVE in 1999, and it was quickly embraced. Some of the relevant milestones are:

- Year 2000—Over 40 products were declared compatible with CVE. CVE is used by 29 organizations.

- Year 2001—Over 300 products and services were declared compatible. CVE is used by more than 150 companies.

- Year 2002—NIST recommends the use of CVE by U.S. agencies. NIST SP 800-51, Use of the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) Vulnerability Naming Scheme, is released. SP 800-51 was updated and renamed in 2011. The current name is Guide to Using Vulnerability Naming Schemes.

- Year 2003—The CVE Compatibility process is started. This process allows products and services to achieve official compatibility status.

- Year 2004—The U.S. Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) requires use of products that use CVE identifiers.

- Year 2007—NVD implemented several upgrades to the CVE-based database. These upgrades increased usability and improved the scoring system. Many other entities have since adopted the NVD, which has increased the use of the CVE as a standard.

- Year 2008—CVE provides major updates to multiple cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities. CVE was mentioned in a December 29, 2008, article entitled “Microsoft Denies Vulnerability in Windows Media Player” on SCMagazine.com.

- Year 2009—The database is updated to include major security vulnerabilities across several media and search engines. CVE celebrates 10 years with more than 38,000 vulnerabilities catalogued.

- Year 2010—CVE expands reach and recognition. CVE was mentioned in an article entitled “Securing Voice Over Internet Protocol (VoIP)” in the June 2010 issue of Hacking.

- Year 2011—CVE is mentioned in the December 12, 2011, release of the DHS’s “Blueprint for a Secure Cyber Future: The Cybersecurity Strategy for the Homeland Security Enterprise” on the DHS website.

- Year 2012—CVE gains new recognition. CVE, Common Weakness Enumeration, and the CWE/SANS Top 25 Most Dangerous Software Errors are mentioned in an article entitled “Supply Chain Risk Management” in the March/April 2012 issue of CrossTalk: The Journal of Defense Software Engineering.

- Year 2013—CVE revamped its numbering format for identified vulnerabilities. The MITRE Corporation announced that the CVE list will start to publish data using the Common Vulnerability Reporting Framework (CVRF). The CVE list is a dictionary of common names for publicly known information security vulnerabilities in software.

- Year 2014—CVE is cited in numerous major advisories, posts, and news media references related to the recent Network Time Protocol vulnerability affecting Apple and Linux operating systems.

- Year 2015—CVE is included in a September 2015 technical report entitled “Security in Telecommunications and Information Technology 2015” on the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) website.

- Year 2017—CVE celebrates providing common identifiers for publicly known cybersecurity vulnerabilities, including everything from relatively minor flaws, such as missing HttpOnly flags, all the way to headline-hitting exploits, such as EternalBlue.

- Year 2018—CVE list passes 100,000 entries.

- Year 2019—CVE is now 20 years running.

The FBI/SANS Top 20 List of the Most Critical Internet Security Vulnerabilities also references the CVE list.