6

EXPLOIT EMERGING OPPORTUNITIES

UP TO THIS POINT, this book has dealt primarily with existing markets and industries having reasonably definable boundaries. In this chapter, we examine those rare instances in which significant changes have led to the creation of entirely new markets or industries. We shift from looking at customers, segments, and industries to looking at the dynamics that sometimes lead to major shifts in needs, which in turn can lead to major opportunities.

Chapter 5 looked at forces that affect all players in an industry— you and your competition together. The issues we explored there had to do with exploiting more or less regular trends and cycles at an industry level. In this chapter, we talk about opportunities that emerge when a confluence of shifting factors comes together to create an entirely different strategic landscape from the one you have been working with. If chapter 5 was about capitalizing on dynamics you see first, this one is about anticipating a phase change in the competitive environment.

The metaphor we like to use to describe these sorts of shifts is that of a tectonic plate shift. Tectonic plates lie under the earth’s continents and are constantly in motion. A tectonic plate shift occurs when numerous small things accumulate to reach a breaking point. What is interesting about tectonic plate shifts in economies is that their advent often can be anticipated. It’s also interesting that the rise of a new industry usually benefits new firms that form around the opportunities it represents, and not established firms, even though one might think that the latter have the competencies and skills to take advantage of them.1

Creating Customers: What Works?

First, let’s acknowledge that few established firms become successful quickly in brand-new markets and industries. The very practices that go together with long-term reliable success tend to be inimical to success in new environments.2 In a few cases, however, companies have pulled it off, and their stories represent the last class of marketbusters that we address in this book.

Some market creation is driven by the vision of a person at the top—often the CEO, although not always. Occasionally, the vision actually provokes the changes that lead to a major industry shift. Steve Jobs at Apple is justifiably famous for envisioning whole new market spaces—not just once, as with the personal computer, but repeatedly, both successfully and unsuccessfully. His wildly successful company Pixar, for example, was formed to capitalize on the development of digital media animation, whereas his NeXT computer (an early PDA) was a disappointment. Most recently, Jobs’s Apple Computer has developed devices to take advantage of the emergence of the “digital jukebox” for music. Unfortunately, individual genius is hard to reproduce with any reliability.

Behavior that requires a little less overwhelming insight, but that does require senior intervention, is to identify a tectonic shift and mobilize the company to go after it. A well-known example is Microsoft’s about-face on the importance of the Internet after the company initially dismissed its significance.

Another, albeit unreliable, vehicle for capitalizing on industry change is called slack search by academics.3 In this method, you create free resources at the operating level, resources that empower employees to explore interesting opportunities in a relatively undirected way. Unfortunately, this frequently used method is unpredictable and often unsuccessful. Often, such groups are not given sufficient time, cannot integrate with the parent organization, end up being eliminated during cost cutting, or otherwise become regarded as expensive deviants by their parent organizations. A variant of this strategy is to pursue new spaces through partnerships, such as strategic alliances or industry consortia. Similar risks pertain. Tools that we have sometimes seen such groups use to good effect are scenario planning, heavyweight internal champions, and various forms of exploratory sense-making.4

Another practice that can prove fruitful is to follow the entrepreneurs. Look at where start-ups are entering and use their activities as a cue to do likewise, or use corporate venture capital to provide a window on interesting developments. Or you can buy a partial stake in a smaller company. Similarly, you might consider building partnerships with universities and other centers of innovation.5

Sometimes an established firm causes a new market to emerge purely on the basis of its own clout. Perhaps the most famous historical example is the way in which IBM’s entry into the personal computer market created an alternative standard to the Apple II overnight and established a market that—although nascent with Apple’s innovation—grew rapidly only after IBM made a commitment to it. As of this writing, Intel is attempting a similar move in the world of wireless communication chips for laptop computers, IBM is seeking to create a market for “on demand” computing, and companies such as America Online are seeking to develop a market for “bring your own access” Internet experiences.

Why It Is Hard to Capitalize on New Markets

When envisioning new markets, companies often make a number of critical mistakes. First, because the shift that represents the emergence of an opportunity is often small, they may not see the trend as significant. Even Microsoft missed the early signs that the Internet would become significant. More frequently, existing players are wedded to an alternative solution that would be threatened by a major change. RCA, for example, failed to capitalize on transistors because it was dependent on vacuum tubes and didn’t try to take advantage of the emerging opportunity.6 Sometimes, the change is so threatening that established industries seek to fight it. Consider the music labels’ history of fighting every successive wave of new technology in that industry, from 33-rpm albums to the advent of downloadable music. Sometimes companies move too early. The personal digital assistant market, for example, saw dozens of hopeful firms enter and exit before the PDA finally became a mass-market product.

To see a tectonic plate shift coming, you must put together many bits of seemingly uncorrelated and sometimes seemingly unimportant information. When we are scanning and gathering intelligence to keep an existing business going, rarely do we fine-tune our activities to spot evidence that a new business may be emerging.

It is also hard to see the utility of a new solution before it has been experienced. Market research won’t tell you very much about a market that doesn’t yet exist. Until a certain amount of cumulative marketplace experimentation has built up, it’s hard to see what the real opportunities will be.7 The difficulty is that if you take on the burden of doing all that experimentation, there is no guarantee that your firm will reap the rewards; after you have demonstrated that an opportunity exists, others can easily follow your lead and capture the benefits.8

Further, new markets often start small and fall into market segments that are not considered mainstream.9 That makes them hard to spot, because again no amount of market research that reflects your current understanding of who is buying your offerings will help you understand customers that you don’t serve in markets that it never occurred to you to approach. Why did the Victor Talking Machine Company not dominate radio, and why did existing watch-makers miss the emergence of electronic watches? The reason is that the customers for those new products were a different group from those served by these companies, so they couldn’t use existing customers and needs as a guide to where best to innovate.

Foreseeing a New Market: The Tectonic Triggers Table

As with chapter 5, where we discussed the forces that can lead an industry to dramatically change, here we are concerned with those forces that can lead to the emergence of a new market.10 Economist Leon Walras long ago articulated the fundamental source of value in an economy as the combination of utility and scarcity.11 In considering whether a new industry might be emerging, we are looking for shifts in perceptions of utility (usefulness, desirability) among large groups of potential customers, and shifts in the scarcity (or uniqueness) of solutions.

If value is created because an offering addresses some need or want, a logical question is, what causes needs to change? To answer this question, you’ll need to look at longer-term trends and changes in the environment. Some companies have a formal process for doing this, such as the famous scenario planning group developed by Royal Dutch Shell, the use of macro-trend studies by DuPont, or the reports issued by the Institute for the Future for its consortium clients. Essentially, these techniques call for firms to look at sets of correlated possibilities to envision possible futures.

Firms such as these study situations in which a change in technology enables new solutions that formerly were not possible. New drugs, for example, create markets by allowing treatment for disease states that previously were not addressable. The Internet allows e-mail communication to operate asynchronously, speeding up written communication and in many cases replacing verbal communication.

As with the second-order effects of industry trends discussed in chapter 5, technological progress often leads to second-order problems. These are often counterintuitive, seeming to obey the law of unintended consequences. Thus, we see Xerox copiers that are so advanced that counterfeiters use them to copy currency. Making cars theftproof through radio-controlled keys increases the incidence of both carjacking and key-seeking burglary. The prevalence of cellular phones provokes countermeasures to render them unworkable in environments such as hospitals, restaurants, and theaters. It has also led to a shrinking market for conventional pay telephones. Legitimate antiterrorism measures create risks to privacy, which are sure to provoke still more innovations that seek to disable those same measures.

Other trends might include changes in social possibilities. The emergence of working women and widespread international travel have created a myriad of new opportunities, from franchised day care to frequent flier programs. The two world wars introduced massive shifts in social behavior and markets. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, have created vast changes in the way companies operate and in the technologies they deploy to maintain safe and secure facilities. Demographic changes are interesting, too (and are often predictable).12

Changes in nature also provoke new needs. Global warming, the advent of new diseases such as AIDS and SARS, and even shifts in weather patterns can create new types of demand. Another source of change concerns institutions, such as government regulations, trade barriers, tariffs, tax laws, and myriad rules of the game.

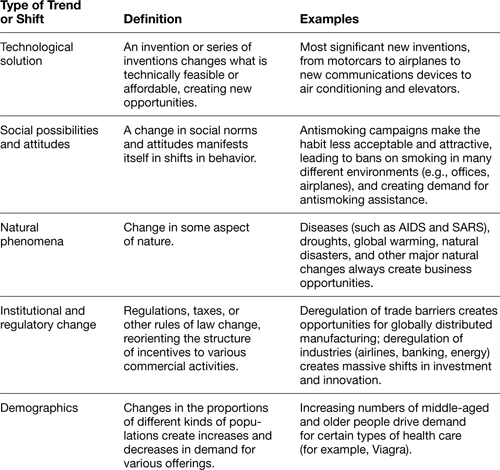

Table 6-1 summarizes these forms of triggers for a tectonic plate shift.

These major types of trends illustrate the ways in which markets can change quite fundamentally. We don’t purport to offer a primer on scenario or trend analysis.13 Still, we suggest you give some thought to these questions:

TABLE 6-1

Tectonic Triggers

- What is your process for developing a point of view about future trends?

- Do you pay enough attention to changes that might create substantial opportunities?

- Is your point of view about the future communicated to and integrated with the people leading your innovation process?

Three Ways of Organizing Trend Analysis for MarketBuster Prospecting

Assuming that you have a process in place for assessing trends that might be important, the next step is to determine whether some kind of significant opportunity might be emerging. To do this, we propose to focus on three simple ideas.

First, consider the need you might address. Needs can be either longstanding or the new result of a major tectonic shift, so we categorize them as either existing or new. Sometimes great opportunities emerge from new solutions to old problems, whereas at other times the need itself is new. Each of the two categories has its own strategic implications.

Second, what solution might address the need? Again, the solution might call on capabilities or competencies you have already developed (perhaps in solving some other need), or it could be new. In general, it is easier and less risky to create a solution based on at least some capabilities you already have.

Finally, you’ll need to consider the adequacy of existing alternative solutions. Ironically, the perceived adequacy of existing solutions to particular needs can often open an opportunity to develop a new need category, as Christensen has often pointed out. These opportunities can be remarkably fruitful for entrepreneurs, because they are not necessarily obvious to other potential new entrants.

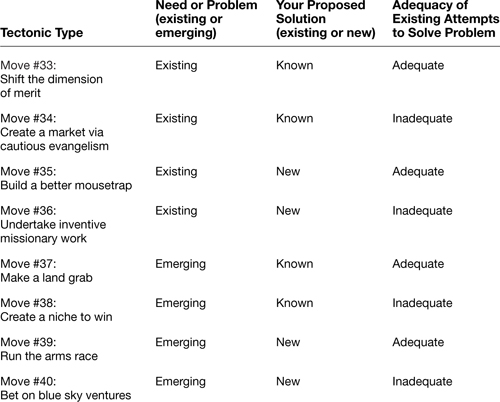

Assessing these constructs can give you an idea of whether you might have an opportunity in a rapidly growing market space. Putting together various combinations of the three constructs allows you to develop a typology of potential opportunity types and understand what it takes to be successful in each one. The result is eight potential marketbusting moves, as summarized in table 6-2 and listed here (continuing the numbering as before, to bring us to our complete set of forty moves).

Move #33: Shift the dimension of merit

Move #34: Create a market via cautious evangelism

Move #35: Build a better mousetrap

TABLE 6-2

Eight Marketbusting Moves to Exploit Emerging Opportunities

Move #36: Undertake inventive missionary work

Move #37: Make a land grab

Move #38: Create a niche to win

Move #39: Run the arms race

Move #40: Bet on Blue Sky Ventures

Before we go into these eight opportunities in more detail, we would like to set up the generic prospecting questions associated with tectonic shifts. Then we will take a close look at the challenges associated with each type of opportunity.

Addressing Tectonic Shifts

In a brainstorming session, gather evidence of key trends that might prove relevant to your position in your industry. You will want to pay particular attention to trends that are relevant to the types of tectonic pressures described in table 6-1. See whether these pressures are also beginning to create pressures in other industries. Specify your best guesses as to what changes will have to be made in the current industry offerings to cope with these pressures, and what kinds of skills and capabilities will be needed to deliver these changed offerings. Now categorize the suggested changes in terms of the typology in table 6-2.

After you identify the relevant pattern for your idea, examine the following discussion of the pattern and put together a strategy that addresses its challenges. For instance, in many industries, the confluence of aging populations, aging infrastructure, and internationalization will dramatically influence demand for such products as medical devices, elevators and escalators, and remote monitoring and communication equipment.

Move #33: Shift a Dimension of Merit

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An existing need

- Known solutions

- An adequate current solution

This category of opportunities represents situations in which a firm can prompt a tectonic shift by going beyond the solutions that have so far been offered for well-understood needs. The question is whether your proposed solution not only addresses the original needs that created the industry or market but also appeals to some new or different need that lies dormant in light of the existing solutions. The question is whether customer satisfaction along an old standard of comparison—or as the academics sometimes say, a dimension of merit—might lead customers to look for the next big thing.14

Example: Healthy, but Fast, Food. Subway is a chain of fast-food restaurants. In a departure from most of its industry peers, Subway focuses on exploiting the concept of healthy fast food. Although the problem of obesity has long been with us, in most of the developed world it has reached epidemic proportions. In the United States, for example, the past twenty years have seen a dramatic increase in obesity. Currently, more than half of all U.S. adults are considered overweight (defined as having a body mass index of 25 to 29.9) or obese (defined as having a body mass index of 30 or higher).15

In January 2000, Subway developed its best marketing pitch ever: college student Jared Fogel. Fogel once weighed 425 pounds. Determined to lose weight, he lived on a diet consisting of a Subway six-inch turkey sub for lunch and a twelve-inch Veggie Delite for dinner every day for almost a year. Subway built on Jared’s story to heavily promote its “7 Under 6” line of low-fat, low-calorie sandwiches (seven six-inch subs, none with much more than three hundred calories and each with fewer than six grams of fat).

The move to introduce low fat and health as new dimensions of merit in fast food paid off handsomely for Subway. In 2000, the year Subway introduced its “Jared” campaign, the company’s total sales growth was 47.5 percent, to $4.7 billion.16 Although traditional fast-food chains still surpass Subway in dollar sales (McDonald’s sales topped $40 billion worldwide in 2001, compared with Subway’s $5.17 billion), Subway recently surpassed McDonald’s in one key measure of success: As of December 2001, Subway reported that it had 13,247 shops in the United States, 148 more than McDonald’s. And according to the quick-serve restaurant trade magazine QSR, Subway’s per-store sales growth was about seven times the industry average for the year 2000. Subway’s recent success coincides with— and is credited by some for contributing to—a new consciousness of the hazards of traditional fast-food fare and a push for more nutritious choices.

Not surprisingly, given public pressure and Subway’s success, the other major fast-food chains have begun to offer health-conscious items of their own. Burger King recently introduced the 330-calorie Veggie Burger and has added reduced-fat mayonnaise to its menu. McDonald’s has also introduced a couple of lower-fat options, including a Salad Shaker (with low-calorie, nonfat dressing) and a Fruit and Yogurt Parfait. Additionally, Wendy’s offers healthful choices such as baked potatoes and chili and a new line of “Garden Sensations” salads.17 The dangers of conventional fast food have also been the subject of considerable press attention, such as the recent popular movie Supersize Me.

As the Subway example suggests, creating a marketbuster in this category does not require massive new investment in wildly innovative solutions. It does require the imagination to envision how an existing package of needs and solutions might be subtly shifted. It helps, in addition, if the need you are targeting represents a large or growing issue. It helps even more if competitors are deeply wedded to serving the original set of needs, a practice that will tend to make their response to your move sluggish.

Prospecting Questions for Shifting the Dimension of Merit

Have you uncovered a new dimension of competing that is different from the current standard modes of competing?

Will it appeal to a large or growing segment of the market that is unimpressed with the current competitive criteria?

Are competitors largely wedded to the current criteria?

Has the very success of an existing solution created new problems that you might address?

Move #34: Create a Market via Cautious Evangelism

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An existing need

- A known solution

- Inadequate current solutions

Opportunities in this category are intriguing in that although a need or problem may be widely recognized, attempts to address it have proven inadequate. Perhaps the solution is too expensive, too complex, or too difficult to use. In any case, a new mass market will not emerge unless the market, technological, or cost barriers are cracked. What is often frustrating about such opportunities is that although the potential is often clear, insufficient utility has been created for customers to perceive existing solutions as valuable.

Example: What to Do with All Those Differing Digital Devices?–The development of digital photography, PDAs, and speech recognition all fall into this category. The attraction of instant photos, electronic organizing, and devices that respond to voice rather than to keyboard input has long been recognized, but it took a long time for the relevant technologies to become cheap enough, usable enough, and good enough to attract a mass market following.

Example: A Failed Attempt—the CargoLifter. There are two ways not to tackle opportunities in this category: attempting to create the market entirely by yourself, or making a huge bet on your particular solution. The German company CargoLifter AG offers an example. Its founder, Carl von Gablenz, created the company in 1996 to pursue a concept of building blimps that could operate as “flying cranes.” The idea was to overcome the inadequacy of alternative heavy cargo transportation approaches, such as the use of cargo airplanes. The heavy cargo market has long existed, but in the mid-1990s, as speed became important to many companies’ competitive positions, firms began to seek ways of delivering heavy loads, such as military equipment, efficiently. Of particular interest were solutions for landlocked areas in which sea shipping was inadequate.

CargoLifter’s airships were designed to hover 328 feet above the ground. Special loading frames would then lift the heavy materials into the blimp’s cargo bay. To keep the airship from floating away when it was unloaded, special ballasts were designed that would be pumped full with 160 tons of water. CargoLifter’s key differentiator (and the unmet need, given existing solutions) was that it required no runway. CargoLifter was envisioned to compete against Russia-based Volga-Dnepr Airlines, which had nine Antonov AN-124 aircraft that could carry 120 tons at speeds of 500 miles per hour. Boeing had its version, the BC-17, which could carry up to 80 tons of materials. This plane had been used mainly for military purposes, with plans to convert it to commercial uses. Both the BC-17 and the AN-124 required less runway space than typical commercial airlines but still required runways.

CargoLifter also promoted the ecological friendliness of the airship because it required energy only for propulsion and not takeoff and landing. It reduced road traffic and also had lower emissions than traditional forms of air transportation. One large blimp, the company envisioned, could also perform humanitarian aid by transporting enough food for 25,750 people for fourteen days.

CargoLifter’s backers provided sufficient funds for the company to sink more than $250 million to develop an early version of the blimp. Unfortunately, the project was plagued by both technical and commercial problems. A trial run for an initial customer, Heavy Lift Canada, ended in disappointment when the blimp proved inadequate to the demands of a heavy storm. Other questions about its feasibility were raised, such as the willingness of customers to construct special sites for the blimp, the practicality of pumping so much water into an empty blimp (and emptying it again), and its slow speed and low-altitude flight. CargoLifter’s bold attempt to create a new market for blimp-based heavy cargo hauling has now ended, at considerable cost to shareholders and the German government as well as development partners.

Prospecting Questions for Creating a Market via Cautious Evangelism

Have you uncovered a potential offering that will significantly attend to a problem that is not adequately addressed for a large emergent segment of the market?

Can you present your revised solution in a way that lets you thoroughly test market reaction before you commit major resources?

Are you convinced that this offering will be insulated from rapid matching by entrenched or emergent players?

The CargoLifter story reflects how difficult it can be to try to create a new market through the introduction of innovative solutions alone. In this category, we recommend that firms employ risk-reduction strategies (hence the caution with which we named this move). For example, you might identify a niche market for which the solution you can provide works well enough, and then migrate to the mass market as market and technical uncertainties ease. Another strategy is to mitigate downside risk through the use of alliances or partnerships with key customers.

The principle is that you can’t tell whether something will work in reality when a need has not been adequately addressed before, so it makes sense to be somewhat cautious in your attempt to innovate.

Move #35: Build a Better Mousetrap

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An existing need

- A new solution

- An adequate current solution

This category of potential marketbusters has long caught the popular imagination. The idea here is that you think you can conceive of a better way of addressing a known marketplace need with a better offering, even though existing solutions are perceived as more or less adequate. The challenge you face is to make a sufficient difference to potential customers that they are willing to abandon previous solutions and switch to yours. A point to remember is that incremental, catch-up solutions are highly unlikely to provoke a switch.

Example: Attacking TV Guide with a Lookalike Offering. Giving insufficient thought to just how good or how different a new offering needs to be to get customers to change their behavior has often led to business failures. TV–Cable Week is a good example. The $55 million initiative was undertaken to launch a new television guide to listings, in direct competition to then-dominant TV Guide. Although a huge effort went into conceiving, designing, and writing the new magazine, it simply didn’t provide enough value to persuade customers to switch. The initiative ended up being declared a significant flop for parent Time Life, Inc.

Example: Creation of a New Category: The Machine-Room-Free Elevator. In contrast, when the Kone Corporation of Finland introduced the first machine-room-free elevator in 1996, the key difference to building operators and contractors was immediately obvious. As its name suggests, elevators based on the Kone design can be constructed with the space and architectural constraints of a machine room to contain the equipment that makes the elevator run. This eliminates a significant source of cost as well as makes new building designs feasible. The Kone MonoSpace required less room, offered far greater design flexibility, and was also more ecologically friendly than its competitors. Launching the MonoSpace gave Kone a substantial advantage, in effect creating an entire market for machine-room-free elevators, which are growing in share of the new elevator construction business. It took competitors several years to catch up, by which time Kone had built a formidable position in the mid-range elevator market in Europe, for which the MonoSpace is particularly well suited.

Prospecting Questions for Building a Better Mousetrap

Have you identified an offering that is demonstrably superior on a dimension that is demonstrably attractive to an emergent segment of the market?

If the offering is not demonstrably attractive, can you deliver it at a lower price and still make good money?

Success in this category of tectonic move is likely to go to the firm that offers a significantly better solution that also costs less. Growth comes from expansion of the established market as it converts from a previous solution, but more importantly from new markets for which previous solutions were too expensive or inaccessible. If you believe that the solution you’ve developed really does create an order-of-magnitude difference, then by all means launch aggressively to build first-mover position on solving an intractable problem in a new way.

Move #36: Undertake Inventive Missionary Work

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An existing need

- A new solution

- An inadequate current solution

The advantage of this category of opportunity is that you are not competing with something that has already been identified in the minds of possible customers as an adequate solution to the problem. The disadvantage is that you must undertake the simultaneous creation of a complete solution and the education of a market, a task that increases uncertainty as well as the execution challenges that you are likely to face. This means that growth in this category is likely to be fairly slow. Dramatic growth won’t happen until a major breakthrough in utility is recognized by a large market, and this doesn’t usually occur until considerable experimentation has taken place in many smaller markets.

Example: The Turgid Pace of Voice Recognition Technology Adoption. The commercialization of voice recognition technology is an example of an innovation in this category. Although existing markets for this application can be readily identified, the technology itself is not yet good enough to offer a viable alternative to other solutions, such as data entry by keyboard. Nonetheless, voice applications are popping up in more and more places as the technology crosses the utility threshold for successive niche offerings. Voice commands are now found as replacements for telephone operators, in the Federal Express package pickup request system, and even in applications in mobile phones and in cars.

Example: Innovations in Health Care. There are many fascinating examples in health care in which new solutions have created considerable growth. Medical device manufacturer C. R. Bard, for instance, created a massive advantage for itself by introducing an innovative line of hernia repair products and ancillary services. By dramatically reducing the time and difficulty of having hernias repaired, Bard essentially created a new category of therapies in which it captured a dominant position. Considering that hernia repair is one of the most frequently performed surgeries, this marketbuster has allowed Bard to tap into a large and growing market (details are listed at http://www.crbard.com/news/viewNews.cfm?NewsID=222).

With opportunities in this category, it makes sense to keep downside investments low and to preserve the option to discontinue investment if trials are unpromising.18 Considerable experimentation is likely to be involved, so it doesn’t make sense to promise the boss or your shareholders that innovations here will provide dramatic new growth soon.

Prospecting Questions for Undertaking Inventive Missionary Work

Can you identify places in which large target segments are persistently unhappy with existing solutions? Have you got a potential solution that might work?

Will you be able to build a technically successful offering at limited cost and incrementally introduce it to clearly identified beta-friendly customers?

Can the process of market education and product development be unfolded without major initial resource commitments?

That being said, if this represents a market that you think will be highly significant for your future, you will want to develop early-warning indicators for market takeoff and prepare to move fast in the event that things seem to be coalescing around a particular solution.

Move #37: Make a Land Grab

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An emerging need

- A known solution

- An adequate current solution

Opportunities in this category make wonderful targets for established firms, because what is new is the need or problem to be addressed, but invention does not lie on the critical path to rapid market adoption. Typically, such opportunities arise because resources are made available that did not exist before or because long-term trends have allowed the emergence of a market segment that previously was either too small or too poor to be of much interest. Winning strategies often involve extending established competencies and capabilities to new opportunity spaces.

Example: Teaching America to Eat in Front of the TV. A fascinating example of a major success in this category of opportunity is the Swanson TV dinner. According to company lore, the dinner was created in the early 1950s, when inventor Gerald Thomas was attempting to come up with something to do with 520,000 pounds of leftover Thanksgiving turkey. The meat had not sold, and it was traversing the nation in refrigerated box cars because there was insufficient warehouse space for it.19 Meanwhile, on an international plane flight, Thomas observed the flight crew testing metal trays for serving dinner to international passengers. He pioneered the concept of using a divided metal tray to separate various parts of the meal, solving one of the major objections to prepared pre-cooked meals: that everything ended up as mush.

The TV dinner was introduced to the marketplace in 1954. For 98 cents, a customer got a full meal that included turkey, corn bread, gravy, buttered peas, and sweet potatoes. Along with the trend involving rapid commercialization of television, the Swanson dinners capitalized on the desire for convenience for two-earner families and on Americans’ newfound fascination with home appliances. Nineteen million U.S. women took jobs outside the home during World War II and continued to work after the war ended, creating a new demand for food that required little time to prepare. In 1954, the first year of sales, Swanson sold more than 10 million dinners. Today, Americans consume 3 million Swanson dinners each week.

The TV dinner also influenced a number of secondary industries, including home freezers and microwave ovens. The name “TV dinner” was retired in 1962 to appeal to a broader audience. Today, one of the fastest-growing food segments worldwide consists of prepared, ready-to-eat, or nearly ready-to-eat foods.

Example: Selling to Sporting Women. Changing regulations often trigger the emergence of new needs. In the world of sports, Title IX legislation in the United States, which mandated equal access to funds for men’s and women’s sports, created many new markets for women’s sports equipment and supplies.

Example: Changing Laws. Similarly, regulations can drive the emergence of new markets. Energy-efficiency requirements for automobiles, for example, have been a major driver for efforts by auto manufacturers to produce lighter cars that require less fuel— creating, among other things, the demand for substitute materials. Aluminum, for example, might be used in place of heavier steel. Recent bans of so-called white waste (disposable) products in China have created enormous demand for alternatives made from different materials.

Example: Helping People Quit Smoking. Another factor that can prompt the formation of a new market is a change in prevailing attitudes. For example, aggressive antismoking public relations campaigns and greater awareness of the health risks of smoking (not to mention bans on smoking in many public places) have created a new need for smoking cessation offerings. GlaxoSmithKline has capitalized on that new market with a product designed to help smokers quit. Nicorette gum is an alternative method of nicotine delivery, without the harmful tars that are prevalent in cigarettes. Nicorette is designed to slowly wean smokers from their addiction to nicotine, so that one day they will be dependent on neither cigarettes nor the nicotine delivered by the gum. Given the numbers that GlaxoSmithKline uses—46 million American smokers, 90 percent of whom want to quit and 70 percent of whom won’t see their doctors—the market potential for an over-the-counter aid to quit smoking is enormous.20

Nicorette gum is sold in more than fifty countries and has gained scientific support. Several studies show that by using Nicorette, smokers are twice as likely to succeed compared with using willpower alone.21 Since Nicorette became available as a nonprescription treatment, the number of adults attempting to quit smoking has significantly increased, to nearly 40 percent, according to a study of U.S. Census data presented on February 22, 2002, at the Eighth Annual Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. This statistic adds to scientific evidence that providing over-the-counter treatment options for smokers increases quit attempts.22

Prospecting Questions for Making a Land Grab

As you evaluate the trends in your markets, are new needs emerging that you might have a solution to address?

Are there growing areas of persistent unhappiness or unease among your target segments?

Have segments become newly aware of social or other issues that might prompt a change in their behavior (such as certain industry categories falling out of favor, new health concerns, social changes with respect to acceptable behavior, and so on)?

Are you sure that your solution works for the target segment? Has it been validated by the market?

Do you know how to advertise, promote, distribute, and service the market? Do you need to do it yourself, or can you use existing infrastructure?

Although there are no exact numbers available on the size of the stop-smoking market, the change in consumers’ attitudes toward smoking indicates a huge potential for growth. In prescriptions, the market is valued at approximately $263 million. In 1998, sales of over-the-counter nicotine-replacement products exceeded $568 million, according to Information Resources, a Chicago-based marketing research firm. That’s nearly double total sales in 1996, when these products first became available over the counter.23 Nicorette is the sector’s top global brand and is growing by 25 percent per year.24

Firms that win in this category genuinely have capabilities that address the emerging need, possess essential complementary capabilities (such as distribution), and are prepared to move aggressively.

Move #38: Create a Niche to Win

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An emerging need

- A known solution

- An inadequate current solution

Opportunities in this category can be highly profitable early attempts to address a whole new category of problems using existing capabilities. To the extent that your offering is better than alternatives (particularly better than nothing), you can create a substantial business as the market emerges and develops. The real risk of this kind of market is that better solutions are likely to emerge, because the problem that drives market growth has not yet been solved.

Example: Growing Through Increased Demand for At-Home Health Care. The growth of home health care product distributor Osim International was built on this form of tectonic customer shift. Osim’s story began in 1980, when its chairman and chief executive officer, Ron Sim Chye Hock, set up a sole proprietorship in Singapore that sold kitchen appliances and household goods. Dr. Sim eventually diversified beyond household products to retail handheld massagers and blood pressure monitors. In expanding his product line to home health care products in the 1980s, Dr. Sim took advantage of an emerging set of customer needs focused loosely on taking care of oneself rather than going to a doctor or spending time in a spa to get a massage.

Busy lifestyles meant that time-pressed consumers were actively looking for alternatives to conventional approaches. Furthermore, people also showed that they were willing to do things themselves, thus eliminating waiting time and inconvenience. (Note that this trend also supports the success of other products and services, such as home test kits for diseases and developing family pictures.) Shifts in customer demographics and customer attitudes have also helped Osim’s growth. Over the years, Osim’s customer base has grown and changed. In the early 1980s, most of Osim’s customers were in their late forties and early fifties, with many suffering from back or joint aches. Today, the bulk of Osim’s clients are baby boomers aged thirty-five to fifty-five, for whom buying a blood pressure monitor or home sauna is a lifestyle rather than health decision.

Prospecting Questions for Creating a Niche to Win

Can you identify small markets with new needs that are wealthy enough to afford to have the need met?

Have you developed something new in terms of products or services that might prove compelling to a customer group you have not served before?

Is the initial market large enough to minimize cash burn, or will you be able to capitalize on a large long-term market? If so, can you gain rapid dominance of the emerging market and lock out competitors?

Can you protect the long-term market well enough that you can build it without losing your profits to competitors?

Today, according to market research firms The Gallup Organization and ACNielsen, Osim International is one of the top brands of electronic health care products in Singapore and Hong Kong. Dr. Sim hopes to increase the number of outlets worldwide from 203 to 1,000 by 2008. In July 2000, Osim International launched its initial public offering and was listed on the main board of the Singapore Exchange. Since 1989, Osim has enjoyed strong growth every year. In FY 1999, turnover rose 48 percent (to $103.1 million) and net profits tripled, from $2.3 million in 1998 to $7.7 million. In Q1 2002, Osim International posted 23 percent growth in profits (to $3.2 million) on a 22 percent higher turnover of $42 million. The company reported growth in all five of its key markets: Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, China, and Malaysia.

In short, opportunities in this area can be considered a niche, at least at first. The key challenge is to gain penetration in the niche and then grow as the market grows.25 Be aware, however, that as long as the solutions remain inadequate to the market’s emerging needs, you will be vulnerable to someone else coming along with something even better than you can offer.

Move #39: Run the Arms Race

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An emerging need

- A new solution

- An adequate current solution

Opportunities in this category are among the most likely to inflict significant damage on those firms that pursue them. That’s because many players are likely to perceive as attractive a substantial new need having a satisfactory solution, creating significant competitive entry and a likely eventual shakeout. In some cases, however, the solution you can provide is actually different from that offered by others and is protected by entry barriers, in which case this becomes a most attractive opportunity.

Example: Capitalizing on Rapid Growth in Demand for Wireless Internet Connections. This pattern is playing out in the market for gear that facilitates wireless networking in the home and workplace. An early winner has been Linksys, a company founded in 1988 and premised on the concept that cheap, usable networking (an emerging need) would offer significant opportunities. The Linksys offerings, targeted at home and small-business users, have been so successful that they dominate about 39 percent of the market for networking solutions by these users and have led to the acquisition of the company. Linksys has made Inc. magazine’s list of fast-growing companies for five consecutive years, showing the power of addressing early needs with compelling solutions. Linksys was recently acquired for a healthy premium.

Example: The Rise (and Fall) of Discount Brokering in Germany. Far more common than Linksys’s happy (at least so far) story are tales of firms entering attractive-looking markets, only to find that they are facing far stiffer competition than expected. Discount brokerages in European countries offer a cautionary example. As regulations began to permit discount brokers to operate, entrepreneurial firms such as Germany’s ConSors entered with enthusiasm. Initial assumptions were that Germans, and other Europeans, would begin to trade with the same enthusiasm that Americans had, that the rising stock market would continue to provide incentives to trade, and (implicitly) that non-European firms were unlikely to enter with brokerage products. Initially, ConSors enjoyed dramatic growth, and its experience was widely reported in the media as a genuine Internet success story.

Unfortunately, as the new market proved to be attractive, others noticed, prompting massive numbers of new entries. In 1999 alone, sixty new players entered the market in Europe, and E*Trade, DLJDirect, Citi, and Schwab all announced intentions to expand in that region. Worse, the dramatic market reversals of 2000 depressed the appetite for trading, decreasing revenue from margin buying. ConSors ended up being acquired, and its parent company, Schmidtbank, found itself in bankruptcy (not entirely due to Con-Sors’s fate).

So markets such as these are indeed wonderful opportunities, but the watchword is caution; you need to know how you will be insulated from competition, and you must be mindful of the many other players that are likely to be just as hungry as you are for the growth opportunities.

Prospecting Questions for Running the Arms Race

Are you confident that you can get a reliable solution in place quickly and profitably?

Are you being encouraged by the target segment to attend to this problem?

Are these customers willing to place advance orders—at good prices? Do you have a win-win?

Are they willing to take on beta models and learn with you?

Will you be able to protect your long-term position?

Move #40: Bet on Blue Sky Ventures

As shown in table 6-2, this move has the following pattern:

- An emerging need

- A new solution

- An inadequate current solution

Stop. Take a deep breath. Before moving any further with this category of opportunity, ask yourself the following questions:

- Are you prepared to wait three to five years or longer for this market to drive substantial growth?

- Do you have sufficient slack resources to sustain your efforts with respect to this market?

- Do you have management processes in place to appropriately recruit, compensate, reward, and respect people who are working on projects that are likely to be regarded by the rest of your firm as cash sinkholes?

- Are you prepared to tolerate many disappointments to learn what the business really is?

If you answered no to any of these questions, this type of opportunity may be very unattractive for you, at least in the near term. Don’t say you weren’t warned!

We have termed these kinds of opportunities blue sky ventures because they represent new-to-the-world problems, with new solutions that no one has yet figured out. In effect, you are dealing with problems people aren’t sure they have, solutions that no one has yet experienced, in ways that may not even be technically feasible.

We’re not saying that these kinds of opportunities aren’t important. They are, because they can actually change the world and make a huge difference to your organization. We are saying that profiting from such opportunities is highly uncertain, and it will require considerable patience and adroitness from you as a manager. For these reasons, history suggests that success often goes to firms that are not incumbents in the affected industries.

Example: Pharmaceuticals, “Smart” Devices, and Clean Energy. A market that has the flavor of a blue sky venture includes new treatments for previously untreatable diseases, particularly those that stem from genetic problems affecting a subpopulation. Developing medications that are tailored to a specific genetic profile might be an example. Various forms of intelligent personal communication devices—such as “smart” clothing—probably also fall into this category. A host of innovations in the areas of clean, green energy, hydrogen-based batteries, and renewable fuels also fit this category.

Succeeding in ventures of this nature deserves far more comprehensive treatment than we can offer here. Fortunately, several excellent resources will point you in the right direction if you believe that you have an irresistible opportunity for the long term. To get started, see Block and MacMillan’s Corporate Venturing: Creating New Businesses within the Firm and Leifer et al., Radical Innovation: How Mature Companies Can Outsmart Upstarts. Our previous book, The Entrepreneurial Mindset, also offers some useful tools for thinking about new-to-the-world types of businesses.26

Prospecting Questions for Betting on Blue Sky Ventures

Has no other approach recommended in this book shown you a less risky alternative, or are you so convinced of the enormous upside that you simply must go for this particular brass ring?

What evidence do you have of a huge upside, a controllable downside, and the sustainability of future profits?

The reality is that such businesses are apt to take a long period of sorting and experimenting to become genuine growth businesses. By imposing upon them the kinds of constraints and expectations that are appropriate for mature businesses, large organizations perennially mismanage these new ventures. They do, however, represent the most substantial risks for established organizations, which tend to dismiss or deny their potentially disruptive effects. Finding a new solution to a problem that was previously ignored is also a huge opportunity for entrepreneurs—pay no attention at your peril!

Action Steps for Exploiting Emerging Opportunities

Step 1: Audit your firm’s orientation to the future by asking the following questions:

- Do you have a process for systematically pulling together information about the key trends and shifts that are likely to characterize your markets?

- Do you engage in future thinking, contingency analysis, scenario planning, or other ways of anticipating the future?

- Do you collect data that will help you see a trend in progress?

- Does your senior team spend enough time thinking about your own customer tectonics? Do people in your main functional areas also consider this topic?

- Are you alert to emerging needs and emerging sources of dissatisfaction in your key customer segments?

If the answers to these questions are no, it makes sense to begin to develop a better sense of the future. As a way to get started, we suggest something simple—perhaps allocating some time, say half a day each quarter, to think about future trends and get some input.

Step 2: Identify those trends that you believe may have an important influence on the needs of the customers you are already serving. What new needs might be emerging? What new solutions to existing needs might be emerging?

Step 3: Identify those trends that you believe may have an important influence on needs of customers you are not currently serving but that might prove important in the future, because they exist in markets that are adjacent to yours or because they may represent important growth opportunities.

Step 4: Speculate on how you might capitalize on the trends that you articulated in steps 2 and 3. What would make it worthwhile or crucial to take some action at this point? Do any of the trends represent a long-term risk to your business that suggests the need for immediate attention?

Step 5: Categorize the opportunity in terms of the moves shown in table 6-2. What does this tell you about your major challenges?

Step 6: Create a screening approach to determine which opportunities are worth further investigation. Then sort them into those you wish to pursue and those that you will leave for later.

Step 7: Establish a small working group or task force with the responsibility to flesh out the concept. (Be prepared to allocate resources to the members, and make sure that at least one of them is devoted full-time to exploring the possibilities.)

Step 8: For those markets that you consider to be most promising for your firm, begin to flesh out the resistance analysis table described in chapter 7.

Step 9: Decide how you might develop a project to pursue those opportunities you consider to be most important. Which of the following will you select?

- An innovation project driven from the senior level (as with the Apple Macintosh).

- A separate group with isolated resources dedicated entirely to the opportunity (the classic “skunkworks”).

- A project folded into the ongoing work of a significant operating division. (Caution: This is likely to be successful only if the leadership of the division sees the market-creating activity as consistent with the current drivers of success for this group.)

Step 10: Initiate the project, bearing in mind the need for clarity of purpose (what defines success) and frequent stock-taking and testing of assumptions. Be prepared to stop or redirect the project should it appear to be heading off course.