3

TRANSFORM YOUR OFFERINGS AND THEIR ATTRIBUTES

IN CHAPTER 2, we encouraged you to try to get into your customers’ point of view in order to understand the experiential context in which they consume your products or services. In this chapter, you’ll look through a different lens to discover what your offerings really mean to your customers.

The critical question is how the attributes (features or characteristics) of your offerings are positioned relative to your customers’ view of other offerings and to your customers’ expectations. It’s as if you’re charting your position on a map, because essentially you are trying to develop insight about your relative position.

The tool we use to get at this insight is what we call an attribute map. Attribute mapping simplifies the complexity of your proposition to your customers and your position with respect to competitors. In this way, attribute mapping lets you clearly see how a move might have an impact and also gives you objective information about the likely consequences of a move.1

Let’s begin with the bad news. There will always be things about your offering that some customer segments dislike. Further, a lot of what you take time and effort to deliver is either not visible to the customer or not a factor that differentiates your product or service from the competition. Finally, the whole process of creating value for customers is dynamic: Yesterday’s major differentiators become tomorrow’s taken-for-granted attributes. Not fair. Not nice. But that’s how it goes in open, competitive markets.

The good news is that by developing a fine-grained view of how specific segments react to specific attributes, you can develop offerings that maximize the value customers perceive, while optimizing your investment. The idea is not to offer attributes that cost you money to create but which customers don’t value; you do want to seek those rare attributes that can make a huge competitive difference, even if they aren’t that expensive. An attribute map, shown in table 3-1, gives you a tool that helps you understand and respond to your customers’ real needs and desires.

An attribute map describes your offering in terms of what it does to please, or displease, key customer segments. Along the rows are the reactions of a target customer segment to the features in your product or service. The top row shows those features and attributes that customers regard positively; these attributes might prompt them to purchase and stay loyal to your products and services. The features in the second row are the negatives; these are things that customers dislike and would prefer to do without. In the third row are attributes about which customers are neutral. They don’t care, or don’t know, about these features.

Table 3-1

The Attribute Map

The labels of the columns try to capture how your offering stacks up relative to other ways customers might meet their needs. If customers judge that a feature is basic, it means that they take it for granted that all competing products have that feature. The middle column lists discriminating features—those attributes that cause customers to judge one offering to be superior or inferior to another. The third column shows energizing features. These are attributes that, as far as customers are concerned, dominate the decision to buy and use the product or to contract for the service. They typically evoke a powerful emotional response that can overwhelm everything else you do.

Positive Features

A positive feature that is regarded as basic is one that the target segment expects to receive. We call these nonnegotiables. You need to be realistic about nonnegotiables; although you may spend enormous amounts of time and energy on them, as far as the customer is concerned they are taken for granted. Not having this basic characteristic means that this segment will simply not buy from you. Having this feature does not mean that people buy any more, pay any more, or value what you do any more. The frustrating thing about the nonnegotiable category is that it tends to be where companies spend the bulk of their time, investment, and infrastructure, but sadly, most of that effort is taken completely for granted by their target segments.

In the middle category of the top row in table 3-1 are differentiators. These are attributes that distinguish your offering from competitors’ in a positive way and give you a favorable competitive position. (Similarly, your competitors’ differentiators are what attract their customer segments to their offerings and not to yours.) Having differentiating features is great, and it can form the basis for competitively differentiated pricing and positioning.

Even more powerful are a class of attributes we call exciter features. Exciters are so overwhelmingly attractive to a particular customer segment that they not only distinguish you from competitors but also so delight the customer that they can constitute the basis for buying and using your offering. Exciter features plant the seeds of considerable competitive advantage.

Fascinating misconceptions abound regarding exciter features. Managers tend to believe that there is a correlation between the expense and difficulty of including a feature and the resulting excitement on the part of customers. Often this is simply not so. Exciters can be, and often are, technically simple changes that add to the convenience or ease of using the product. Hewlett-Packard, for example, is currently receiving rave reviews for designing ink-jet printers that not only produce high-quality printed photographs (a nonnegotiable) but also use photo memory cards from many manufacturers directly as inputs, thereby eliminating the need to use a computer and greatly enhancing the ease of use of the printers.

Incorporating exciter features can help you overcome drawbacks in your offering. The original success of the PalmPilot handheld device has often been attributed to its ability to overcome the weight and size limitations that plagued previous personal digital assistant (PDA) devices, although admittedly its display was not very attractive and having to learn its Graffiti writing method was awkward for many customer segments.

Negative Attributes

All products have negative attributes, so it’s important to be explicit about them. First come tolerables. These are attributes that customers put up with to get the positives you offer. As with nonnegotiables, customers assume that tolerables come with the product and that buying from a competitor will not eliminate them.

When you think about it, most industries have many tolerables. Airlines require you to suffer security searches. Credit card companies charge interest on revolving debt. American movie theaters have sticky floors and smell like popcorn. At a minimum, all companies want you to pay for what they provide when—let’s face it— we’d all rather get what is being offered for free.

The key issue here is that if a competitor can figure out how to eliminate tolerables when you still force them on customers, you can suddenly find yourself at a competitive disadvantage. A great many entrepreneurs have enjoyed big wins by recognizing attributes that customers simply tolerate because no one has yet invented a better way to remove the problem attribute at an acceptable cost. If you invent a way around tolerables, the whole product value equation can change.

When customers believe that a negative attribute of your offering could be avoided by buying a competitive offering, it becomes a dissatisfier. Dissatisfier features differentiate you from competitors, but in the wrong direction. Thus, cars that are perceived to require excessive service, fees perceived to be too high, technical departments thought of as unresponsive, and the like can all drive your customers away.

Even more deadly to your competitive position is a class of attributes that are energizing but negative. We call these enragers, although they may inspire many negative emotions, ranging from anger to fear to disgust. Obviously these features are never the result of a conscious decision; rather, they emerge as the result of misjudgment or even outright misfortune. When Monsanto attempted to launch genetically modified agricultural products in Europe, the company seriously underestimated the negative emotions such products would engender. As it turns out, Europeans are far more aware than their American counterparts of issues surrounding genetic modification, and a vocal, emotional constituency mobilized almost instantly to oppose the launch. Interestingly, it turns out that American consumers, whom Monsanto executives assumed accepted genetically modified foods, are spectacularly unaware of how many of these products they actually consume.

If you are unfortunate enough that an attribute becomes an enrager, a terrifier, or a disguster, it is critical to eliminate it before it busts your market. The reputation of once-dominant Perrier, for example, was so sullied by a highly publicized case of contamination that Perrier has never recovered its former market share. If you cannot eliminate an enrager, you may have to exit the enraged target market.

Negatives are a rich source of marketbusting opportunities, particularly because many firms tend to focus all their attention on working the positive line. Adding value, creating more features, and bulking up the product with enhancements all seem to be popular, but they overlook opportunities created by negatives. Apple Computer’s “switch” campaign, for example, is targeted at customer segments who are enraged by the unreliable performance and lack of usability of their “Wintel” computers. Apple is betting that there is a large group of customers who might be willing to pay more and endure the negative of a conversion hassle to own a computer that doesn’t crash, boots up quickly, and handles routine chores with aplomb. The devices look good, too.

If you want to gain great insights into negatives as your customers see them, the best source is to talk to the people who come into direct contact with customers or distributors. Sales, service, complaint handling, returns processing, call center, and accounts receivable staff are all likely to be exposed to customers who experience your offering, often in its worst possible light.

Neutral Attributes

Target customer segments are indifferent to neutral attributes, so in general they are not sources of marketbusting ideas. However, products can have features that are neutral from the perspective of one customer set but are basic or differentiating for a different customer set. Because neutral attributes add cost without enhancing value, one major marketbusting opportunity is to ruthlessly eliminate the culprits and thereby drive down cost and hence price. Be careful, though; for some customers, things you might think are neutral are actually nonnegotiable. For example, replacing a live person with a voice-mail system may be perfectly fine under some circumstances and deeply upsetting to customers in others.

Parallel Differentiators

Parallel differentiators are the features mapped in table 3-1 as neutral. These features have nothing to do with the functionality of the product or service as such but are offered in parallel with your offering and actually induce the purchase. For years, McDonald’s has differentiated its fast-food offerings for families by offering a children’s meal. Called a Happy Meal, it comes in a special box—often imprinted with entertaining games—and includes a toy. Children’s meals give families a reason to choose McDonald’s over other potential providers of quick food, although when you think about it they aren’t really a necessary part of the food consumption experience. McDonald’s has recently added grown-up happy meals to their product offerings—extending the insights gained through serving families with children. We like to include such parallel features in a strategic analysis because often they are overlooked.

Applying Attribute Maps

An even better way to systematically identify opportunities for differentiation for your different customer segments is to conduct attribute mapping of the most important consumption chain links. Make sure that you are aware of which attributes fall into which categories for key customer segments at each link in the chain, because you can then begin to ask questions such as these:

How can you deliver the positive attributes faster, better, and more cheaply and more conveniently than you do now?

How might you reduce or remove negative and neutral attributes?

How can you meet new needs that customers may be developing?

What might customers find attractive if you alone could give it to them?

The answers to each of these questions will give you a sense of the opportunities you have to move from the attribute maps created today to the marketbusting offerings that can drive profitability tomorrow.

Possibly the most important way to use an attribute map is to anticipate the dynamics of change in what customers will value and what competitors will respond to. Yesterday’s exciters? Tomorrow’s nonnegotiables. Yesterday’s tolerables? Tomorrow’s enragers. Yesterday’s so-whats can easily be tomorrow’s tolerables, particularly if they add cost or complexity for the customer and yet add little value. When an exciter becomes a nonnegotiable, you really want to be in a low-cost position. Many people forget this, in the joy of discovering something customers really value and will pay for. Remember, competitors won’t let you keep your exciter features to yourself if they can possibly find a way to match you. Why? Because for the period when you have sole control over an exciter feature, you are creating an ever-more-powerful ability to compete, a major disadvantage for them.

Missing the Obvious

It is easy for companies to offer innovations that are not sufficiently meaningful to induce customers to change their purchasing behavior. For example, dozens of credit card companies fill the mailboxes of the affluent on a daily basis, offering low-interest or no-interest cards and the opportunity to combine balances. For this group of consumers, who typically don’t run balances and don’t care about the interest rate, the offered change in consumption experience creates no value. In contrast, when credit cards were first made available to students without requiring parental cosignature, it created a substantially different customer experience, with the result that student uptake was enormous. In the case of student cards, competitors of firms such as Citibank initially were not inclined to match the offer because they didn’t understand how to accurately price the risk of offering cards to students.

A second mistake is to forget to design a profit capture mechanism before you introduce an innovative move. This was perhaps the largest problem facing many dot-com companies. Their management teams failed to recognize that creating value from information goods is entirely different from being paid for value created. Management in a host of failed dot-coms, such as the ill-fated Value America.com, thought simply that offering a new channel would alter customers’ experiences and take share from existing players, but the model that would generate huge profits never fell into place.

A third common error is to fail to focus the segmentation effort finely enough that offerings can be fine-tuned for those groups who value them the most. Consumption chains are different for different segments, and therefore changing them will have different value for different segments. Often, companies try to alter the consumption chain for everyone they might conceivably do business with, without thinking through which segments will really be excited by the offer. Time Warner’s failed “full service network” venture, for example, was based on the assumption that interactive television would be of interest to its entire customer base, most of whom (the company thought) would leap at the chance to order movies and shop interactively through their television cable systems. The company eventually lost more than $5 billion on the venture.2

A further mistake many companies unfortunately make is to fail to anticipate competitive responses to their moves, thus creating no vehicle for protecting their profits from competition. Competitors can learn from you about how to improve the consumption experience for their customers, often destroying your advantage. The history of discount stores, for example, shows a consistent pattern of progress in which pioneers’ innovations were superceded by later entrants. Innovations pioneered by Woolworth were improved upon by operations such as Kmart, Best, Inc., and Caldor. Eventually the whole sector came to be dominated by Wal-Mart (whose premise is “everyday low prices”), leading to large-scale closures among previously successful competitors. Without some way of isolating your profits from competitors or competing in a way they find difficult to match, you can guarantee they will come after your profits.

Projecting Your Profit from a Move

In textbooks, there is no shortage of analytical techniques for assessing how likely you are to benefit from an investment in improving some aspect of your offering. In reality, we find that managers often either won’t or can’t take advantage of the advice in textbooks because they are not forced to take a candid, hard-nosed look at how their offerings stack up in reality.

We often see a tendency to gloss over who the competitors are to begin with. It is common to sit in on strategy debates and observe that the discussion never goes beyond the traditional competitors or sticks to such a generic view of competing offerings that it can’t be a focus for action. The offerings of possible competitors are dismissed because they are assumed to be inferior in customers’ eyes on some dimension such as quality or comprehensiveness. But before you feel secure, it’s a good idea to check whether customers really want all that quality and comprehensiveness.

Second, companies often underestimate how rapidly competitors might respond to a move. One insurance company we worked with was furious that competitors responded to a proposed new product with the launch (soon after) of a look-alike product, which evidently was a straight copy of the original. Worse, because the copycat company didn’t have to invest in market research and development, it was offering the product at more favorable rates than the innovators.

Third, it is important to remember that not all people running companies are trained as entrepreneurs or business strategists. They can sometimes overlook business basics, such as remembering to ask how a particular advantage will be sustained.

And finally, there is a widespread misconception that customers’ response to a change in an offering will somehow be proportionate either to their overall levels of satisfaction with the change or to the effort and expense the company went through to offer it. Instead, marketing research suggests that customer responses to whatever a company does tend to be curvilinear: Some moves evoke a powerful, behavior-changing response, whereas others create a far more muted reaction.

A Sample Attribute Map: Home Internet Access

We thought it might be fun to illustrate attribute mapping by selecting a product category that is currently driving one of us completely crazy—namely, access to the Internet at home. As of this writing, there are not a great many alternatives in the United States for home access to the Internet. Offerings fall basically into three categories: (1) access through telephone lines; (2) access through high-speed channels, such as cable, ISDN, or DSL lines often hooked to a local area network; and (3) access through wireless devices on a mobile data network.

To start this example, we need to consider segments. In the case of your authors, Rita uses her Internet connection for research— locating examples, teaching materials, and references from various online databases. For these applications, speed and reliability are key attributes. Slow connection speed has a dramatic and immediate effect on productivity. Excite@Home, the local cable company that served Rita’s home area, advertised “blazing fast speed” and actually delivered on this promise when she hooked up to the service. But when Comcast cable took over after Excite’s spectacular bankruptcy, the speed of Rita’s Internet connection fell off dramatically, creating frustration on her part (and on the part of everyone in her family who listened to all the complaining!).

Interestingly, Rita falls into a different segment for Comcast’s purposes than someone who is converting to cable from a dial-up connection. For a former dial-up-only customer, the speed is probably an improvement. For someone used to the fast access speed of the previous system, however, the speed provided was frustratingly slow.

What would this example look like in an attribute map? Let’s try mapping a few of the following features for Rita that are featured in Comcast’s advertising:

- Always-on access, no dial-up

- “Comcast at home” sign-on screens

- Speed of service (transmission, download, and upload speed)

- Personalized log-on screens

- Access to proprietary content

- Comcast e-mail address, Web pages, and “my file locker” feature

- Price: $49 per month

These attributes are shown in the attribute map in table 3-2.

For Rita, who has an e-mail address provided by Columbia Business School, together with a Web site and other file storage features, the e-mail and file features of Comcast are neutrals—she simply doesn’t care. But for other Comcast segments, these features are probably extremely important. Connection speed, however, is so important to segments such as Rita’s that if Comcast were faced with any real competition, Rita would have been highly likely to switch providers.

TABLE 3-2

Attribute Map for Rita’s Broadband Features

Further, because Rita’s segment uses the service for work purposes, price is less important than is speed. Other characteristics of the service—such as pop-up ads that request that users download software they neither need nor understand—can add to the dissatisfiers in the map. For example, this morning Rita had to deal with an irritating pop-up inviting her to download some sort of video playing software. Her reaction? “What is that? Why do I want it?”

If one were strategizing for Comcast, maps such as this one suggest issues that deserve attention. The monopolistic nature of cable service offers the company some breathing room. However, dissatisfaction with the service might easily lead Comcast to lose customer segments such as Rita’s when an alternative becomes available— even at a higher price. The company could flag other alternatives, such as differentiating on price (perhaps having speed-conscious segments pay more). Each segment would be uniquely influenced by Comcast’s choices. Finally, Comcast would need to be extremely careful in the event that enough customers become enraged to push for a challenge to its monopoly position.

It is only fair to say that after about six months of what appeared to be teething problems in digesting the Excite@Home acquisition, Comcast’s service is once again back to acceptable levels and has been quite reliable, and Rita is once more a loyal customer. Now, if it could just do something about all that spam and adware. . .

MarketBuster Prospecting

The point of attribute mapping is to create a framework for thinking about changes you might make to your offerings for a targeted set of customers. Being conscientious about such mapping also leads you to confront competition and clearly define various segments. It can also give you early warnings about competitors’ moves and motivations.

Searching for potential marketbusting moves can be a simple matter of picking up a few key attributes for certain key segments. It can also, if needed, involve a fair amount of detailed work to help you understand what is driving the consumption experiences of your customers and how your offering fits into those experiences. At the extreme, you would go back to the consumption chain you developed for your offering and, for each key segment, construct an attribute map for each link in the chain. But seldom is this amount of detailed work necessary. Instead, you can begin by mapping two or three of the most important links, such as the usage link, the purchase link, and the selection link. It is also important to recall that your specific offering may have peculiarities that require special handling. For example, if your main business is repairing elevators, your customers really don’t want to see you in their buildings during rush hour.

Here are seven moves companies have used to shift the attribute maps for their offerings and create marketbusters (we’ll continue the numbering from chapter 2 to make it easier for you to find a move that interests you):

Move #6: Dramatically improve positives

Move #7: Eliminate tolerables or emerging dissatisfiers

Move #8: Break up existing segments

Move #9: Infuse the offering with empathy

Move #10: Add a compelling parallel offering

Move #11: Eliminate complexity

Move #12: Capture the value you deliver

One of the beauties of attribute map moves is that often you can combine them to make an offering even more compelling. For example, if you can improve positive attributes and add a parallel offering, the move has even more potential to be a winner. In several of the examples we describe, you’ll notice that companies changed their customers’ attribute maps along several dimensions, not just one.

Move #6: Dramatically Improve Positives

An obvious place to look for a new potential marketbuster is to consider how you might dramatically enhance your offerings by adding powerful new differentiators or, particularly, by adding exciters. Most managers we work with enjoy thinking of ways they can better serve, please, and appeal to customers. Most ideas, however, represent opportunities that competitors will find difficult to follow quickly or be reluctant to adopt quickly. A quickly copied addition does nothing more than raise the cost of doing business.

Example: Procter & Gamble Makes Electric Toothbrushes Massively More Affordable. An interesting example of a dramatically changed offering is Procter & Gamble’s latest twist on the common toothbrush—the SpinBrush. Powered by a tiny battery, the SpinBrush is an inexpensive electric toothbrush with a rotating head. Invented by three entrepreneurs and sold to Procter & Gamble, the SpinBrush put an attribute—a moving brush head—into the market at a price point that is competitive with high-end manual brushes.3 The result was a product that dramatically changed the world of brushing, or at least of toothbrush marketing. As of this writing, it is sold in 35 countries, has contributed $200 million in global sales, and has forced competitors into an uncomfortable reactive position involving discounts on their previously higher-priced products. In the first quarter of 2003, the sales of the Crest franchise—led by new products Whitestrips and Spin-Brush—rose 30 percent and were expected to grow healthily throughout 2003.

Example: Enterprise Rent-A-Car Leases Cars to Businesses First, Consumers Second. As its name suggests, Enterprise Rent-A-Car started in the primarily business-to-business (B2B) target segment. It delivered an attribute to replace one that was temporarily unavailable: specializing in car leases to firms, such as insurance companies, that needed replacement cars while owners waited for their damaged cars to be repaired. From these beginnings the firm has grown from car rental to fleet rental to one of the largest vehicle leasing and car rental companies in North America, with revenues of $6.9 billion.

Example: Intel Expands the Mobility Attributes of Personal Computers. The introduction of Intel’s Centrino mobile technology delivers new notebook computer capabilities designed specifically for the mobile world. Now it is possible to work, connect, and play without wires, as well as to choose from a new generation of thin, light notebook computers designed to enable extended battery life. Although the apparent target may be the individual customer, the bulk of Centrino sales are to firms whose high-value, highly mobile employees need to be connected as seamlessly as possible to their professional environments. The Intel Centrino brand also ensures that you don’t need to study a technical manual or use special equipment to connect. That’s because Intel worked with hardware and software developers and wireless service providers with the goal of delivering an integrated wireless mobile computing experience. Laptop computers equipped with the technology come with wireless connectivity and extended battery life—a compelling differentiator for professional people on the move.

Example: Ricoh Manages Total Printing Output for Customers. In Japan, Ricoh has aggressively added major positive attributes to its offering over the past twenty years. Starting as a provider of sensitized paper, Ricoh moved early into digitization and progressed from printing equipment to printing solutions—that is, total management of printing output. Now Ricoh has added a new set of positive attributes: document solutions. This offering lets users completely digitize and store documents, photos, images, data, and other types of input. For document-driven businesses, document solutions allow for flexibility of output production, including conversion of black and white to color. This strategy maximizes the propensity of customers to use Ricoh consumables such as quality papers and colored inks and gels (which have many user-friendly properties that ink lacks).

Prospecting Questions for Improving Positives

Differentiators

To determine your offering’s positive differentiators, have your customers from the key segment answer the following questions:

Why do they buy from you and not the competition?

What do you offer that they not only like but also are prepared to pay a premium for?

What does your offering do better than anyone else’s?

How close is the competition to matching you on these features? Are you progressively reducing the cost of providing these features?

Exciters

Have your customers from the key segment complete the following sentences:

I would buy (or pay) more if, when I use it, I could. . .

I would buy (or pay) more if, when I buy it, I could. . .

I would buy (or pay) more if, when I select it, I could. . .

Move #7: Eliminate Tolerables or Emerging Dissatisfiers

Often, rather than add new positives, it’s more powerful to find a way to eliminate tolerables or dissatisfiers. This move creates a positive for you while simultaneously creating a possible dissatisfier for your competition.

Example: The “Run Flat” PAX Tire. An interesting example is the Pax “run-flat” tire introduced by France’s Michelin Group. The run-flat tire contains technology (invented in part by DuPont) that permits a driver to travel fifty or more miles after a tire sustains damage. This tire technology eliminates several drawbacks, in particular the need for drivers to stop and either change the tire or wait for roadside assistance when a puncture occurs. An additional benefit is that the tire is so reliable that it eliminates the need to transport a heavy spare tire, with a concomitant saving of fuel cost, weight, and space. Among the negatives of this offering are that it requires redesign of the car chassis and some other elements. It remains to be seen whether the “run flat” concept is powerful enough to overcome these negatives.

Example: Sweeter Smelling Stables. At the more entrepreneurial end of the spectrum is a move made by a relatively small operation, a hunter/jumper equestrian center known as Canterbury Tails in the Princeton, New Jersey, area. The business was begun by horse enthusiasts Elissa and Larry DiPano, who decided to enter the market for boarding and training show horses, which in the United States alone involves some 5.5 million horses at prices in the hundreds of dollars per month. In 1996, the pair started working on their dream by focusing on the negative attributes of existing offerings. One negative they identified was smell. Most stables, they found, were constructed with ventilation flowing up and down a center isle, meaning that when any inhabitant urinated, the air in the whole stable was perfumed. To eliminate this negative, the entrepreneurs built a facility with cross-ventilating windows in the stalls. They also addressed other major negatives in competitive offerings. The business opened its doors in 1998 and now is in the black, offering boarding and lessons in a uniquely customer-friendly environment for the horsey set. Moreover, some see the stable as a leading provider with potentially marketbusting consequences at a national level. Witness the following observation, reprinted from a local newspaper:

John Reiley, supervisor of operations, has his own prediction. Between heaving bales of hay into the stalls, he puffs, “I’ve worked ’em all—Belmont, Monmouth, Hialeah, and scores of private stables. And I tell you one thing—this is the best run outfit I’ve ever seen. They’ve made it a goldmine. Ten years from now? Hell, they’ll have to beat customers away with a stick.”4

Example: An Appeal to Security in Flying. Discount air carrier JetBlue has made an effort to add to the emotional content of its marketing message. After the terrorist attacks of 2001, reassurance of safety became an increasingly significant customer requirement. JetBlue was the first national carrier to install bulletproof, deadbolted cockpit doors on all its aircraft. Although this safety measure may well be required by the Federal Aviation Administration in the near future, JetBlue is trying to act in advance to show that its main focus is on safety and meeting its customers’ needs and wants. At the time of this writing, JetBlue is also the only airline that has implemented a full bag-matching policy (matching all checked bags to passengers on board its domestic flights) to further increase security. These processes serve to reassure customers who are deeply fearful of plane security.

Example: Providing Supplies to Individual Small Medical Practices. PSS World Medical (originally Physician Sales and Services) provides supplies to medical practices, focusing its attention on private practices; the idea is that the doctor, dentist, or other provider needs and is willing to pay handsomely for personalized attention, updated product information, and similar service needs. Among other features of the service are no shipping costs; even though orders are small, they have a high margin. With revenues of more than $1 billion, PSS serves more than one hundred thousand practices.

Prospecting Questions for Eliminating Tolerables and Dissatisfiers

Tolerables

What are the features that your most important segments would list if you asked them to complete the following sentence: “If only you could eliminate _______ from your offering, I would buy (or pay) a lot more”?

Can you get rid of the tolerables in ways that competitors can’t? How?

Are you experiencing increasing complaints about a feature or characteristic?

To what extent are your target customers beginning to compare you to your competition unfavorably with respect to this attribute?

Dissatisfiers

Which attribute do people who interact with customers hear the most grumbling about? Is it something all providers do? Is it something only you do?

Is this attribute increasingly cited as a key reason for customers returning the product or discontinuing the service?

Are any competitors claiming that they are superior with respect to this attribute?

Move #8: Break Up Existing Segments

In a disruptive resegmentation move, your goal is to break apart existing segmentation schemes by changing the attributes offered to customers. Perhaps a particular segment is underserved, or perhaps you have identified a new or emergent need that is not addressed by current offerings.

Example: Local Delivery of Office Supplies in Tokyo. Japanese office supplies firm ASKUL has focused on a much underserved B2B segment: the small office. Small to medium-sized offices in Japan have been largely ignored by major stationery stores. Before ASKUL, someone had to be dispatched to the local small stationery store, where urgently required items often were not in inventory. ASKUL developed a sophisticated distribution network organizing these local stationery stores to deliver office supplies the next day (ASKUL means “comes tomorrow”). Now if you call, fax, or e-mail in the morning, the items will be delivered the same afternoon. This saves our colleague Ichiro Suzuki at T. Ohe & Associates, for example, a good sum of money because he no longer has to pay someone an hourly wage plus transportation costs to get urgent office supplies. Even larger regional offices are starting to use this service because it saves the several days it typically takes to get an order delivered.

Example: Leapfrog the Establishment. A powerful form of resegmentation involves leveraging insights into buyer behavior or changing buyer behavior to create a favorable segment. This approach was taken by upstart Econet Wireless International, a private firm founded by Zimbabwean entrepreneur Strive Masiyiwa. Econet’s goal was to become a major force in Pan-African telecommunications, in direct competition with the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications, which runs the state-owned Posts and Telecommunications Company (PTC). Originally, the PTC denied Strive Masiyiwa a cellular license. Masiyiwa hired a team of lawyers and, after five years, won the right to compete for cellular customers on December 31, 1997. Ironically, the very inefficiency of the PTC created a receptive market for a more efficient service based on the GSM global standard, even for those customers with a landline installed. Econet’s strategy focused on eliminating the negatives with respect to government offerings and creating positives, such as affordable and reliable cell phone service that could be obtained quickly.

Masiyiwa focused his marketing efforts directly on the deficiencies of the state-run system. He sought to change the behavior of existing PTC customers and, more importantly, to offer an alternative to those who were not yet telecommunications users. Econet’s initial target customers were opinion leaders and academics who would create a sense of legitimacy for Zimbabwe’s first private telecommunications offering. Against a background of notoriously inefficient government operations, Econet presented itself as a company that was standing up to a corrupt government system. The entrenched ZANU PF party had been losing the support of the urban population because of its failure to halt the rapid decline of the Zimbabwean economy. State-run enterprises were notorious for corruption. For many customers, using the Econet service was viewed as making a political statement against corruption and supporting the success of an enterprising fellow Zimbabwean.

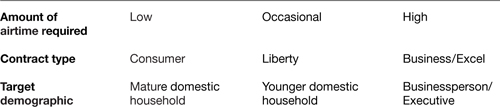

Political philosophy aside, Econet still faced the problem that many potential users were resource-constrained and would be leery of agreeing to use potentially expensive cellular phones. The company therefore developed a wide range of options tailored to the needs of customers having differing capabilities to afford services. The flagship offering is a service called “Buddie Pay as You Go,” a prepaid cellular plan with airtime bought by the user in advance. The main marketing message is that this is a way to control one’s budget, an important feature in a volatile economic climate (2001 inflation, for example, is estimated to be 300 percent). The company has also tailored packages to cater to various behavioral patterns of cell phone use, by offering the three contract packages shown in table 3-3.

In addition, Econet pioneered value-added services (for an additional fee). These include EcoFax (a fax message forwarding service), Ecomail (a personal answering service), Executive Briefing (a news access service), News on Demand (news content broadcast through the cellular phone), Eco-Note (a short message service), Roaming (for travelers), and a Crisis Center offering that makes rapid linkages to emergency service providers.

From its founding on September 10, 1998, Econet’s market share has expanded to 48 percent of Zimbabwe’s mobile operator market (one hundred thirty thousand subscribers). Econet is now moving rapidly into Kenya, Nigeria, Malta, Lesotho, and Botswana, with the objective of becoming a Pan-African telecom operator. It currently is the third largest.

TABLE 3-3

Econet Contract Packages

Example: Leveraging Interest in Music into Retail. Retailer Hot Topic has resegmented a portion of the market for apparel, accessories, and clothing by focusing entirely on young men and women aged twelve to twenty-two who have a passion for music-licensed and music-influenced clothing and other items. Demand for Hot Topic merchandise has been fueled by the popularity of music videos on television channels such as MTV and the ubiquitous marketing efforts of popular artists. The company opened its first store in 1989 in California and operated 274 stores as of February 3, 2001, in forty-five states across the United States. Its slogan “Everything about the music” suggests a differentiated position that the company has been able to maintain, even in the face of intense, mall-based competition seeking to serve the teenage segment. We guess that most readers of this book will not be up on the latest in such products as navel rings styled to resemble those of the wearer’s favorite singer, but you heard it from us: The segment is large and is willing to spend money. In 2003, Hot Topic stores attracted enough shoppers to turn in $443 million in sales.

Hot Topic offers an amazing variety of goods—some ten thousand stockkeeping units’ (SKUs) worth, all with a music-oriented theme. For a retail company, Hot Topic’s financial track record has been extremely strong. The company first sold stock to the public in 1996 and today has a market value approaching $400 million.

Prospecting Questions for Breaking Up Existing Segments

Underserved Segments

Is there any current or emerging segment that is being underserved by the current attribute maps for major links in the consumption chain?

Are there trends that might give you the opportunity to break apart an existing segment?

Behavioral Segmentation

Have you looked at how various people behave at various links in the chain?

Can you segment by creating a set of attributes that will appeal to the need that customers are seeking to address at the moment that behavior becomes important?

Have you considered common behaviors that cut across demographic segments—for instance, when some customers simply want to be taken care of with little fuss while others prefer a more personal touch?

Move # 9: Infuse the Offering with Empathy

We work with a fair number of companies that are heavily populated by engineers, scientists, and trained analysts. It never fails to intrigue us how often our superrational colleagues are surprised by the success of an offering that doesn’t perform better or cost less but is kinder, funnier, or more meaningful than competitive offerings. One powerful place to start looking for a marketbusting chance is therefore to consider ways that you can enhance a customer’s experience. You can either add attributes that make your offerings nicer and kinder or remove those that make it hostile and unfriendly.

Example: Eco-friendly Reusable Packaging. Japan-based Starway Inc. developed environmentally friendly reusable packaging for office equipment such as computers and printers and further streamlined the process of transporting the equipment by offering pickup and delivery services. Seiko Epson used Starway’s service and cut package costs and pickup and delivery fees by 50 percent. Companies such as Epson Direct use this service in their repair operations. Customers call Seiko Epson for repair services, and Seiko Epson in turn calls Starway to pick up the printer and package it for transportation. The truck operator quickly puts the printer into Star-way’s reusable package and brings it to Seiko Epson’s repair office. After the repair is completed, the truck is again dispatched to pick up the repaired printer and deliver it to the customer in the reusable package. At the customer site, the driver opens the package and installs the repaired printer. The driver then returns the reusable package to Starway. Seiko Epson pays for using Starway’s system and still saves 50 percent over the cost of the previous approach, which involved single-use packaging and a variety of logistics providers. The customer benefits because there is no need to dispose of the package. Seiko Epson (and other electronics manufacturers) wins, Starway wins, the customer wins, and the environment wins.

Example: Adding a Touch of Humor to a Serious Subject. Another of our favorites is the legal service company behind the Web site www.expertlaw.com. In addition to referrals to private investigators and expert witnesses, this firm provides a catalog of lawyer jokes under a heading called “legal humor.” Here’s an example:

Q: What’s wrong with lawyer jokes?

A: Lawyers don’t think they’re funny, and other people don’t think they’re jokes!

What we found interesting about this example is that if you search on the Web for the phrase “legal humor,” you fairly quickly unearth www.expertlaw.com, providing the firm an inexpensive bit of potential awareness building and a point of differentiation from many other Web sites that offer the same services.

Example: Videos for the Smarter Baby. Looking for opportunities to make your offerings more empathic is a good time to start watching for those experiences that customers find frustrating, alienating, or even frightening, or to take note of those they find cool, interesting, or useful. One entrepreneurial idea we found appealing along these lines is a company called Baby Einstein, which produces videos for babies. The company founder, new mother Julie Clark, invented the concept when looking for a way to introduce her children to music and art at a very young age. Together with her husband, multiple-venture entrepreneur Bill Clark, she founded the business—which five years later was sold to the Disney organization for a reputed $25 million—with an initial working capital of $5,000.

The videos themselves are very basic, with black and white backgrounds, full-screen images, and simple, short material—for instance, variations on classical music played one note at a time or cartoonlike images of famous paintings. The Clarks’ understanding of what would appeal to babies also appealed to parents, who greatly enjoyed watching their offspring quietly absorbing the videos rather than squirming or crying. The great success of this business depended entirely on empathy, particularly the warm feeling parents get from a combination of gaining a few uninterrupted minutes and the potential advantages of their newborns’ exposure to art and culture. Even the name of the company suggests upper-middle-class striving!

Example: Trendy Clothes for the Larger Teen. Hot Topic, mentioned earlier, plans to attempt a new marketbuster by introducing a retail concept called Torrid to attend to the clothing needs of young obese women. Torrid will offer a selection of apparel, lingerie, shoes, and accessories for plus-size women between the ages of fifteen and thirty. This concept came to the attention of company management because members of the target segment persistently requested clothing in larger sizes than Hot Topic’s normal range but tailored to the same sensibility that has driven Hot Topic’s growth. Women in this segment felt largely ignored by existing providers, creating a resegmentation opportunity. Although there is an increasing concern with obesity as a health risk, this segment does appear to be substantial.

Example: You’re a Star! EasyJet, a U.K.–based discount carrier, enjoys an unusual brand of empathic connection. In January 1999, a series titled Airline was transmitted on Britain’s ITV, giving a “warts and all” account of life for passengers and staff at easyJet. (Airline was one of the very first reality shows.) By June 2000, more than 40 percent of the viewing public was tuning in to the show, which had more loyal viewers than the new version of Friends. Equally empathic, the easyJet Web site allows guests to select their preferred language and provides access to a variety of travel options, including access to cobranded services provided by easyCar and easyInternetcafe.

Example: Cracking the Upgrade Treadmill. Small businesses are constantly faced with the paralyzing decision of whether to upgrade their computer systems and face “upgrading obsolescence” by having next-generation systems released shortly afterward, or to hang in and run the risk of falling behind in IT technology. Direct Leasing has found an empathic solution by absorbing the obsolescence risk for firms that lease computers from it. If your current leased equipment is obsolete, Direct Leasing will help you manage the transition to the new system.

Prospecting Questions for Infusing Empathy

Adding Empathy

Can you redesign the offering at any link to make the customer experience more enjoyable?

Can you make the customer feel more satisfied, safer, more confident, less frustrated, more secure, or more amused?

Behavioral Attuning

Are the attributes you offer a good fit for the target segment’s behavior?

Have you taken these customers’ financial, social, and attitudinal perspectives into account when designing the offering?

Move #10: Add a Compelling Parallel Offering

Just as they often overlook changes that can make products and services nicer or friendlier, companies often overlook opportunities to differentiate their products by offering something in parallel with them. The additional offering may not do anything to the features or functions of the original offering, but it can greatly influence your customers’ experience.

Example: Classical Music with a Difference. If we were to ask you to guess the name on the label that appears on five of the fourteen million-selling classical music compact discs, would you guess that the name is Victoria’s Secret? Part of The Limited organization, Victoria’s Secret is a purveyor of ladies’ racy lingerie. Think about it: As consumers shop, the music plays, and then right there at the checkout is the CD. If one is shopping for a special occasion, why not pick up the music that would. . . uh. . . enhance the experience? Further, unlike a classical music expert, who might venture unafraid into a music megastore, lingerie shoppers can buy albums already put together by experts, with an assurance that the music will be appropriate. Interestingly, the trend toward music compilations that fit a retailer’s theme has now spread to many other stores and store environments, creating a new category for music consumption: music designed to be enjoyed in parallel with other activities. Thus, Starbucks provides music for the caffeinated, Pottery Barn offers tunes appropriate for “Dinner at Eight,” and Gap offers music to go with its cool clothes.

Sometimes you can differentiate even the most commoditized of products by adding a compelling parallel offering. The parallel has nothing to do with the product per se but can create the incentive to buy or to stay loyal. Airlines, hotels, bookstores, credit card companies, and even pizza stores are using a variety of twists on the frequent buyer theme to offer parallel offerings to their best customers in the hope of keeping them loyal. For airlines, a frequent flyer program can outweigh other choice criteria, such as the time and location of a flight. It’s even better if the miles are going toward a family vacation, because the parallel effect multiplies as beloved partners encourage their loved ones to stay true to one provider in order to earn that last free ticket.

Example: A Purchase from Us Is a Vote Against Corruption. Econet, the Zimbabwean telecommunications company we discussed earlier, believed that a powerful parallel offering to its cellular phone service consisted of its stand against corruption. Using an Econet phone became something of a symbol of resistance and provided an interesting first-mover positioning advantage relative to the entrants now flooding into deregulated African telecom markets.

Example: Enhancing Commodities with Services. In any firm selling commodities, such as fertilizer, industrial gases, metal components, paper, and textiles, the essence of avoiding price-cutting death spirals lies in assembling parallel services, such as assistance with inventory planning, production planning, and process planning, or provision of financing services to reduce the cash pressure of a purchase. In fact, over time, the parallel offerings may become valuable in themselves, and you may then need to take the unpopular step of charging for them, as you will see in the next section. There are two challenges here. The first is to anticipate shifts in the needs of the customer’s consumption chain and position yourself to enhance the commodity you are offering. The second lies in being able to anticipate and astutely prune any parallel offerings that are no longer needed, thereby minimizing the cost of the expanded offering.

Prospecting Questions for Adding a Compelling Parallel Offering

Direct Customer Benefits

Is there anything that you can offer in parallel with your offering that will give you the edge in attracting customers?

Is there anything you can do to make your customers’ experience better, even if it doesn’t seem to relate to what you produce or do?

Indirect Customer Benefits

Is there any way your company or your offering can be associated with something the customer values?

Move # 11: Eliminate Complexity

Have you ever bought multiple generations of a product, only to find that over time so many features have been added that you are actually less satisfied with the later models than the earlier ones? If you have, you have lived through the opportunity for what we call radical surgery, a move to dramatically eliminate complexity. Radical surgery is made possible, ironically, by the very efforts of companies to be responsive and to invest in improving their offerings. Often, firms offer more and more options, functionality, and features to the point that the complexity of the offering becomes a dissatisfier. A potential marketbuster can consist of rediscovering exactly what customers want and will pay for and then ruthlessly eliminating everything that doesn’t meet those two criteria. When the time is ripe for someone in the industry to do radical surgery of the offering, you act as the surgeon.

Example: Simplify, Simplify, Simplify. The proliferation of functions and features that comes with technological complexity can create a fiasco:

Last Christmas Eve, just as Lynne Bowman was preheating her oven to roast a turkey for 15 guests, her daughter accidentally brushed against one of the new oven’s many digital controls. “We heard this ‘beep beep beep,’” recalled Ms. Bowman, a 56-year-old freelance creative director who lives in Pescadero, Calif., “and no more oven. After that, we couldn’t get it to work.” Ms. Bowman’s husband, an engineer, was unable to fix the problem. Nor were any of the assembled guests, half of whom were also engineers. Desperate, Ms. Bowman resorted to the small, simple 1970s-vintage Tappan electric oven in the guest house, which worked like a charm.5

Ironically, the digital intelligence that is supposed to make life simpler often has the opposite effect. Video recording devices have more buttons than one can count, tuning a car radio is an ordeal, televisions now require complex manipulation of remote controls, and even changing the clocks for daylight saving time twice a year can be challenging. Attributes intended to be useful, such as timer settings or environmentally sensitive automatic adjustments, can be enormously frustrating if their use is not intuitive. And some products, such as the software we are using to write this book, do things to your work without your asking it to, often provoking a time-consuming search for a way to undo the changes that were made!

A company that has capitalized on radical surgery is Teac, a Japanese consumer electronics company. It has developed a Nostalgia line of stereo systems that use no digital interface mechanisms at all. Instead, the retro radios feature looks from the past and have simple knobs for analog tuning. You can even hear the static between radio stations! In automobiles, cars such as the PT Cruiser elicit feelings of a less complex era. Similarly, trendy consumer retailer Hammacher Schlemmer is capitalizing on a longing for simplicity by offering record players (yes, the 33-rpm kind) that can be carried around and folded into their own cases.

Example: A Stripped-Down Hotel Experience. The quest for simplicity can also be useful in B2B services. One rapidly growing category in the hotel industry, for example, consists of hotels that provide accommodations for long-term corporate visitors, such as contract employees, people whose homes are being renovated, corporate employees, and consultants on extended assignments. An exemplary company offering services to this segment is Extended Stay America, which operates three hotel brands. The typical menu of hotel services is stripped down; there is no bar, no lounge, no central gathering area. Housekeeping is done weekly, and guests typically handle their own laundry rather than send it to a service. In exchange, guests receive “homelike” amenities such as kitchenettes with microwave ovens and refrigerators, coffeemakers, and a dining table, as well as lower prices than the full-service alternative.

Extended Stay America has enjoyed explosive growth since its founding in 1995, becoming publicly listed in 1997. It is the fastest-growing owned and operated hotel company in U.S. history, and for three years in a row it was named one of the Fortune magazine’s one hundred fastest-growing firms. However, it has also shown competitors the way. According to the American Hotel & Motel Association (AHMA), some seventeen new extended-stay brands have entered the market in the past five years, suggesting that Extended Stay America will be under pressure and that later entrants are likely to face a much more challenging competitive market. Even more intriguing, however, will be to watch the impact on conventional hotels as the stripped-down versions eat away at their markets.

Prospecting Questions for Eliminating Complexity

Are there attributes you could eliminate and thus reduce your cost and potentially the price to the customer?

Are customers complaining about the complexity of your products or services?

Can you readily identify features that many of your target segments don’t care about?

Move #12: Capture the Value You Deliver

We often hear this complaint at seminars: “My business is a commodity! It costs me more and more to stay in business, but the pressures on prices and margins aren’t giving me the payback I need. What should I do?” When we get to the bottom of what is going on, often the issue is that the company is giving away attributes that customers value, hoping to extract higher prices for traditional services. As you saw in the case of parallel offerings, many materials-or components-based suppliers give away knowledge and processes as parallels to sell materials or components, unaware that their knowledge has become the more valuable part of the equation. Similarly, some companies create enormous value for customers simply by participating in a market and thus introducing competition, and yet they fail to reap the rewards.

This brings us to the last opportunity for marketbuster prospecting we’ll deal with here: moves that help you extract a price for providing attributes that you might have given away for free.

Example: If It’s Valuable, You Can Charge for It. A classic example of this strategy in the business services sector was carried out years ago by an acquaintance of MacMillan’s who was put in charge of Standard & Poor’s (S&P) rating service. Our acquaintance realized that the bond ratings S&P was publishing for free were of enormous value to the firms being rated. Because of the S&P rating, these firms found it easier to raise capital and gain legitimacy, in some cases garnering huge advantages compared with unrated firms. The manager decided that henceforth any firm that was rated by S&P should pay an annual fee for the service.

Naturally, firms that had been receiving the rating service for free were initially outraged. Our acquaintance, however, took the position that if they didn’t find value in the rating they were free not to pay the fee—and to forgo being rated. The disadvantages of not being rated far outweighed the fee being charged. This simple decision continues to create a huge profit stream for the company (and similar rating organizations) from a service that was treated as a giveaway for years.

Example: Food-Safe Carbon Dioxide. Another interesting example involves The BOC Group, a global supplier of industrial gases that is involved in a good many commodity markets. One such market is selling the kind of carbon dioxide that beverage companies use to put the fizz into soda and other carbonated beverages. With a little help from a purity scare involving a competitor’s product in Belgium, customers became concerned about the sourcing and mechanics of their CO2. BOC turned this into a competitive advantage, charging for source guarantees and purity assurance services that previously it had largely embedded in its gases offerings. In this case, customers were happy to pay the extra charges to ensure the quality of their supply.

Example: Profit from Customization in a Commodity Industry. Worthington Industries has earned the right to much higher margins in an industry traditionally plagued by thin margins—steel processing—by focusing on orders of any size, deliveries with short notice, and a willingness to customize orders. Worthington has become a $2.2 billion global player, with sixty-one facilities in ten countries on five continents. It was named one of the most admired companies in Fortune in 2002 and 2004.

Prospecting Questions for Capturing Value

Customer Takes Offering for Granted

Are you providing an important service or benefit to the customer but not getting paid for it?

Would the customer not buy if you started to charge?

Customer Benefits from Attributes

Can you generate revenues differently—perhaps by menu pricing?

Can you create an annuity stream? In other words, is there a way to charge a per-use fee or monthly fee?

Wrapping Up

This chapter suggests that a useful way to think about your company is as a translation device between what the customer needs and what you can do. Your task is to get that translation just right so that the price you charge represents fair compensation for the value you create.

Action Steps for Transforming Your Offerings and Their Attributes

Step 1: Put together a working group of people who come into contact with your three or four most important existing or desired customer segments. Describe these segments.

Step 2: Using the group to brainstorm, develop a preliminary attribute map for the most important customer segments. If you have created the consumption chains described in chapter 2, use them as input into the maps. At first, try to get a sense of what the map looks like today, and categorize the relevant attributes.

Step 3: Validate the assumptions in your attribute map by reality-checking them with representatives of customers or customers’ companies (and distributors, if appropriate). Revise the maps.

Step 4: Assemble a marketbusting team containing representatives from the most important links, and begin prospecting for marketbusting moves. Build on the discussion in this chapter to look for opportunities.

Step 5. Categorize the ideas into a table, as shown in table 3-4.

Step 6: Create a plan to tackle priority 1 ideas first and priority 2 ideas next. Evaluate the “hard to implement’” options against the other opportunities you are assessing. Remember to assess the opportunities using the DRAT table, which will be described in chapter 7.

TABLE 3-4

Prioritizing Ideas