2

TRANSFORM YOUR CUSTOMERS’ EXPERIENCE

MOST OF YOUR CUSTOMERS or clients really don’t care about what you sell. They spend little time even thinking about it. In fact, few of your customers or clients are likely to regard doing business with you as an exciting event. It certainly isn’t a highlight in their busy lives. In short, the business issues that seem all-consuming from where you sit often have very little resonance with your customers.

And yet the absolute core of organizational self-renewal is to develop deep insight into what customers do care about and why. In this chapter, we introduce a practical, proven approach to seeing customers the way they see themselves and intelligently tapping into their experiences in order to change their perspective in your favor.1

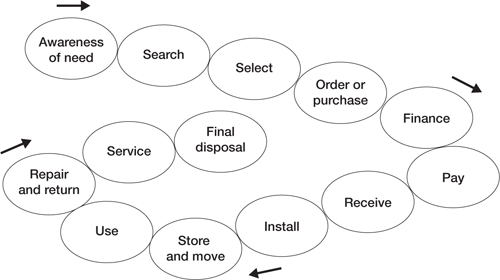

A customer consumption chain, as its name implies, represents the linked sets of activities customers engage in to meet their needs, incidentally doing something that might generate a need for consuming something you sell. Typically, a consumption chain begins with a customer’s awareness of some kind of need and continues through evaluating alternative choices, selecting a provider, arranging a contract, sorting out payment, using the offering, disposing of it, repurchasing or recontracting, generating word-of-mouth referrals, and the like. Figure 2-1 depicts a typical consumption chain for a manufactured product.

If your company is typical of many, you will have sliced and diced the consumption chain to reflect the specialization of your firm’s functional groups. Thus, sales and marketing folks understand the awareness, evaluation, and buying decision links; financial groups understand the payables, credit screening, and billing links; operations people understand what it takes to make the offering work on customers’ sites; and so on.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this specialization; after all, it’s efficient. The difficulty is that your customers evaluate their total experience with your company as a whole. If you mess up one significant part of the chain, the whole relationship can be in jeopardy, no matter how well the rest of the operation performs. Moreover, if you are working with a piecemeal concept of your customers and your competition has a more holistic view, you can find yourself unexpectedly at a major competitive disadvantage if your competitor figures out a way to dramatically improve the overall customer consumption experience.

FIGURE 2-1

A Consumption Chain for a Manufactured Product

Let’s look at a specific example. Here, a company attempts to revolutionize the way logistics and distribution services are sold and used.

Capitalizing on Insights into Your Customers’ Total Experience: Logistics.com

The global shipping and transportation industry accounts for about $3 trillion in expenditures each year.2 Services were traditionally provided by a fragmented collection of players, including freight forwarding companies, trucking companies, various kinds of brokers competing to fill loads of goods by ship, rail, and other means, and logistics operated in-house by producers. Each supplier focused on its own piece of the total shipping system, leaving customers the task of integrating separate offerings to achieve their goals.

The brainchild of MIT professor Yossi Sheffi, Logistics.com grew from a 1988 concept to achieve marketbuster results. The company created a compelling integrated shipping offering through the use of digital technology. Here’s how it works. Traditionally, shippers have sought open bids in an attempt to gain efficiencies (for example, by arranging for use of a single carrier on all three legs of a three-way shipment). A Logistics.com software product, OptiBid, allows shippers to see the impact of various hypothetical routing choices on their costs. In this way, the system encourages carriers to bid more aggressively, based on the prospect of having their costs covered across the complete route. The result is lower total contract prices for shippers and more efficient use of resources by carriers. OptiBid improves the consumption chain for both shippers and carriers rather than only a part of it, as previous approaches did.

Another product, OptiYield, offers decision support for transport providers by giving them real-time information to make cost-saving decisions. Consider a trucking company. To help customers schedule a truck moving across the United States, OptiYield draws on a database of real-time fuel prices, including contract prices for a particular carrier. The trucker might then be advised, for example, to refuel in states having favorable fuel taxes, to change routes based on proximity to cheaper fuel, or to partially fill the tank in anticipation of cheaper fuel availability. Such a decision support system can save trucking firms 6 to 7 percent on fuel costs, which make up about one-fourth of a trucker’s total costs. In this low-margin business, the impact on customers’ bottom lines is substantial.

When we last obtained independent information for the company, Logistics.com managed more than sixty thousand trucks daily and more than 2.7 million shipments annually. In addition, the company licensed its software to third parties. It achieved a growth rate of 80 percent in the first quarter of 2002, securing twenty-three new deals.

Little of this business represents activity that wasn’t being done before in the industry. Instead, Logistics.com has substantially improved its customers’ total experience, taking business away from players who focus on only a few links in the chain. In so doing, Logistics.com has discovered ways of capitalizing on cost savings and better service by touching its customers at many links.

Internet Capital Group, the parent company of Logistics.com, sold the assets of the firm to Manhattan Associates on December 31, 2002, for $21.2 million.

The Critical Problem of Mindless Segmentation

Before you can begin to understand the customer’s total experience, it’s important to consider how you think about sets of customers. We never cease to be amazed by how often companies fail to engage in insightful customer segmentation, relying instead on conventional demographic variables to size their markets and design their offerings. Thus, as table 2-1 shows, companies selling to consumers might develop marketing plans on the basis of customer age, gender, economic status, or geographic location, and business or industrial suppliers might segment their customers on the basis of size, geography, or installation type.

TABLE 2-1

What’s Wrong with These Ways of Segmenting Customers?

There are two problems with using these sorts of segmentation schemes. First, although the segments appear reassuringly quantifiable, demographics seldom accurately reflect customers’ idiosyncratic needs or behaviors. Indeed, there is often as much variation in behavior and preference within demographic segments as there is across segments. This means that the purpose for segmenting in the first place—to finely target an offering to customers’ specific needs—is not well served.

Second, if you can segment on the basis of demographics, so can everybody else. It’s hard to hang onto a competitive advantage if your approach to customers is not differentiated from your competition’s. The same market research firms that sell demographic segments to you can sell them to your competition.

We have no particular objection to starting with demographic segments to get a rough idea of how many target customers you might be considering. We encourage you, however, to go beyond this to capture genuine insights about customer behavior. Many companies have enjoyed good results by employing ethnographic, observational, or anthropological approaches to help them best choose how to serve specific customer groups. The goal is to develop insightful segments based on customer behavior rather than on demographic factors. Although you might think this is Marketing 101 (and indeed it is), we continue to observe plenty of companies that don’t seem to have taken that course!

Understanding a Customer Segment’s Total Experience

Analyzing your consumption chain will also help you to develop differentiated segmentation schemes as you observe that different customer sets behave differently. The goal of a consumption chain analysis is to identify the steps your customers take to satisfy the need they have become aware of (which you can think of as links in the chain), some of which involve their buying something from you.

Some chains are short or simple—for example, the immediate sequence of events that leads a customer to buy chicken nuggets at a fast-food restaurant. Others are long or complex—for example, the sequence of events that leads a steel manufacturer to commission a production facility. The point is that the consumption chain of each potential customer offers a starting point that will help you to gain insight into how you might create an offering with marketbusting potential.

FIGURE 2-2

A Consumption Chain for a Service Business

Earlier, figure 2-1 showed a typical consumption chain for a manufactured product. A different sequence of activities and links applies to a service offering, as shown in figure 2-2. Note that the “service encounter” link repeats, with each repetition representing an opportunity to either capture or lose favor with the customer.

Developing a Consumption Chain

When you construct a consumption chain, your goal is to capture the most important steps a customer goes through. The goal here is not to be compulsive but rather to get a really good feel for how customers are behaving as they try to get their needs met. It’s also important to understand alternative ways customers might behave, because these compete as a way for them to solve their problems.

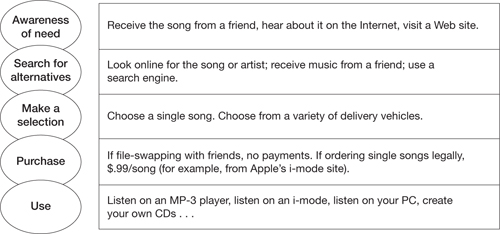

Before we get into the details of constructing your chain, a few words are in order for those who are in an industry facing fundamental changes. Be aware that industry transformations will show up pragmatically as changes in your customers’ experience. For example, consider the plight of companies in the business of producing digital content, such as music or movies. Making money on compact disc (CD) sales used to involve a customer consumption chain like the one in figure 2-3.

What happened to this chain when the potential for purchasing (and swapping) digital music files became a reality? Each link changed. As the links changed, so did the familiar profit model of the CD business. Customers can now easily buy a single song rather than an entire CD to get only the desired song. And, of course, the advent of peer-to-peer music sharing has meant that the “payment” link for some customer segments has disappeared. The chain has been transformed and now looks more like the one depicted in figure 2-4.

FIGURE 2-3

Changing Links in a Transforming Industry: Acquiring Music Analogically

FIGURE 2-4

New Links for Acquiring Music Digitally

As providers of copyrighted materials ourselves, we aren’t wildly enthusiastic about royalty-free content sharing. But when you get beyond the anguish of seeing a profitable business model change drastically, digitization means that some (importantly, not all) customers are clearly interested in a change in the consumption chain for music. Just as this change will make some music models less profitable, it will create tremendous opportunities for others. Several innovative companies—Apple among them—are making a lot of money on alternative ways of distributing music. We can’t say what the next dominant model for the music business will be, but we can say with some confidence that the potential for a marketbuster is lurking there somewhere.

There are many ways to construct a consumption chain. One we encourage you to try is to assemble a group of people from various functions within your organization. Be sure to include people who are in direct contact with customers: sales, marketing, servicing, credit, complaints, repairs, and technical assistance people. Ask them to draw a chain that reflects the experiences they think your customers have with your company.

When you have a chain identified (or in the case of multiple customer segments, multiple chains), engage representatives from all your major customer segments to help elaborate the chains you have designed. Get them to articulate the links that they experience: Becoming aware, searching, selecting, buying, paying, storing the offering until needed, using, repairing, replacing, upgrading, and disposing are all links that they might experience. Your goal is to determine whether there are marketbusting opportunities for you in changing some aspect of this chain.

For industrial customers, this may be the only way to determine where your offering adds value. Anderson and Narus, for instance, reported on an initiative taken by Alcoa Aerospace in which sales-people were asked to chart all the steps a customer took in acquiring, converting, and disposing of Alcoa offerings. To complete their tasks, the members of the sales force had to gain the cooperation of customer employees and, together, agree on the processes. The exercise proved extremely illuminating for both sides, because cost and benefit elements that had previously been hidden were made explicit. Other observers have found that looking downstream from a pure manufacturing position or extending the core business can yield valuable insights.3

How to Construct Your Consumption Chain

- Select a target segment—ideally a segment that you have identified because of its behavior rather than its demographics.

- Identify the people within your company who come into contact with members of that customer segment. (Do you even know who they are?)

- Put together a small task force or discussion group comprising the people in your company who come into contact with this segment.

- Ask them to describe your customers’ experience, from the point of initial awareness of need to the point at which a product is exhausted or a relationship ends (or moves to the next stage). Remember that some customers may have different experiences in different contexts. For example, a CEO acquaintance told us about trying to figure out the consumption chain for his high-end grocery stores. He discovered a strong temporal effect. Monday to Friday, his customers were all about efficiency and convenience. Come the weekend, however, and they turned into gourmet shoppers who wanted luxury, choice, and languor in their shopping experience. This prompted the CEO to reset several aisles in his high-end stores each weekend, catering to the specific consumption requirements of these time-pressed would-be gourmets.

- Create a hypothetical consumption chain by taking various “scenes” from a customer’s experience as the links, noting what transpires to move a customer from one scene to the next (what we call trigger events). Remember: Each business and each segment is likely to have its own way in which the whole chain fits together. Experienced customers, for example, probably become aware they need your offering when something happens to interrupt their experience (such as obsolescence of the existing product or the expiration of a contract or subscription) rather than through advertising.

- Make a critical assessment of how well you are doing at improving that customer’s consumption experience. Are there links the customer would prefer to do without? Are there ways you could serve that segment better? Are there things you are offering that the customer doesn’t value?

- Consider the provocative questions in the section that follows. What can you do to create a better overall customer experience?

MarketBuster Prospecting

You should now have a good understanding of what your customers are going through. The next step is to use the consumption chain to go prospecting for marketbusters. How can you build on the insights of your analysis to dramatically change something about the way the chain currently works to your advantage? Marketbuster prospecting involves asking patterns of provocative questions about how to change the current consumption chain to one that rewrites the rules of the game.

We have identified five marketbusting moves that involve changing the consumption chain.

Move #1: Reconstruct the consumption chain, replacing the existing one with an alternative chain

Move #2: Digitize to combine or replace links in an existing chain

Move #3: Make some links in the consumption chain smarter

Move #4: Eliminate time delays in the links of the chain

Move #5: Monopolize a trigger event

Now let’s look at each of these moves in detail.

Move #1: Reconstruct the Consumption Chain

Here you are looking for opportunities to replace an existing consumption chain with a new one that offers a dramatically different experience for the customer. Amazon.com, for example, made headlines by significantly changing almost every link in the book-buying experience, capitalizing on its ability to influence multiple links. For example, it uses customer referrals to enhance the awareness link, adds a new link by offering a “send this book to a friend” feature, makes payment easier via the “one click” payment system, and even makes money by providing a way for you to resell your used volumes.

Example: Found Money from Loose Change. In the early 1990s, the entrepreneurs behind upstart Coinstar, Inc. (founded in 1991), saw an opportunity in the consumption chain having to do with loose change. For many people, the loose change that accumulates on nightstands and kitchen tables is a nuisance. And it’s a big problem: Analysts estimate that on average $7.7 billion in pocket change circulates in the United States every year.

Traditionally, to turn that change into more manageable paper bills required a tedious process of sorting the coins, rolling them in paper tubes, and taking them to the bank (during normal banking hours, of course). Some products attempted to address a portion of the problem. Automatic coin sorting machines, for example, allowed users to toss assorted change into a hopper, where a battery-operated device sorted the coins and plopped them into preformed tubes.

Although this solution helped by eliminating the sorting link, it didn’t eliminate the hassle of the rest of the links. The coin-sorting machines addressed only a part of the problem.

Coinstar pioneered a new approach that has revolutionized the world of loose change processing: It developed equipment designed to convert loose change to paper cash easily. Coinstar machines, conveniently installed in supermarkets, sort and count the change and issue a coupon that can be used to buy groceries or redeemed for cash at the checkout counter. Think of the impact on the consumption chain: The sorting, rolling, transportation, and refunding links are all eliminated.

Naturally, this service is not free. For a major enhancement in convenience, Coinstar’s customers pay a fee of slightly less than 9 percent of the money converted. Isn’t that astonishing, when you think about it—that customers would be comfortable paying a substantial fee simply to change the form of the cash they have on hand? And yet, developing a comprehensive solution has created a marketbuster for Coinstar. The company’s revenue growth has exceeded 30 percent per year since 2001. In that year alone, Coinstar converted $1.4 billion in coins in more than 9,300 machines. Its revenues for 2003 were $176 million, with projected revenue for 2004 in the range of $178 million to $188 million. Interestingly, Coinstar has also solved a problem for banks, for whom the whole process of dealing piecemeal with consumers’ change problems added cost and produced no revenues.

In 2003, Coinstar began offering other payment-related services, such as replenishing prepaid wireless accounts, activating and reloading Truth prepaid MasterCard cards, and enabling employees of participating companies to obtain wage statements, balance inquiries, and other payroll services.

Prospecting Questions for Reconstructing the Consumption Chain

Can links in the existing chain be eliminated or combined with other links?

Can you completely replace this set of links with some other set? Can you accomplish the same outcome with a different chain? Can you reshuffle the links to improve your customer’s experience? If parts of the chain are a hassle, can you solve the problem in a different way?

Can you create a complete solution to replace a piecemeal solution?

Move #2: Digitize to Combine or Replace Links in an Existing Chain

An obvious way to change a consumption chain is to use digital technology to alter the way you do business. Although the enthusiasm surrounding this idea during the Internet bubble has been dampened, we believe that many companies have turned away from the real advances in digital technology, most of which are materializing only now that we have a decade of experience with the Internet. And there are plenty of Internet experiments to learn from.

Example: Leverage the Internet to Capture Car Buyers’ Attention.–CarsDirect.com was founded in 1999 by Scott Painter and Bill Gross (founder of e-commerce incubator idealab!) after Gross’s frustrating effort to buy a car online through the referral sites that were the only alternative then available. CarsDirect.com was designed to help the knowledgeable buyer complete the entire purchase transaction—including researching, price negotiation, financing, and delivery—online. Through a network of cooperating dealers, CarsDirect.com can consummate such deals without maintaining inventory or the overhead of physical display spaces. In addition, the company has introduced unprecedented transparency in car pricing with an innovative program that uses statistical models to analyze nationwide price distributions. It sets its price within the lowest 10 percent range of the model being bought.

CarsDirect.com experienced extremely fast growth during its first two years. It reported $15.2 million in sales during 1999 and $491 million during 2000, with annual employee growth of 14.5 percent. In February 2001, CarsDirect.com experienced record levels of traffic, reaching 1.7 million unique visitors and becoming the tenth most visited automotive-related site in July 2001.

CarsDirect.com went on to add new channels to its car-selling business model. Launched in 2001, the CarsDirect Connect referral channel gives shoppers the option of being matched with a member of the CarsDirect.com authorized dealer network. This valuable service connects the customer with a knowledgeable Internet representative at a local dealer, who can provide expert advice and guide the buyer through the car purchase process. In 2002, the company launched its comprehensive UsedCar channel, providing the nation’s 30 million used-car buyers with a wealth of free, in-depth research, fast comparison and pricing tools, expert purchase advice, and instant access to more than four hundred thousand late-model cars—all in one convenient online marketplace.

To enhance the original concept of buying new cars online, in September 2002 CarsDirect.com started posting a monthly Best Bargains list. The company’s pricing experts select top new vehicle values from among 170,000-plus price configurations available in the marketplace. The CarsDirect.com Best Bargains list is designed to help consumers cut through the clutter of constantly changing manufacturer rebate and incentive offers by presenting a periodic snapshot of exceptional new-vehicle buying opportunities. Rebate and incentive changes are posted to CarsDirect.com’s Rebates and Incentives Center as they are published by each automaker. CarsDirect.com is the only multibrand car-buying Web site offering this level of real-world price precision.

Of course, the jury is still out on this attempted marketbuster. For one thing, the competition has begun to emulate the same simplification of the consumption chain by enabling the total purchase rather than a referral. Some early competitors, such as CarOrder. com, have already folded. CarsDirect.com has made further efforts to differentiate the customer experience through development of a research facility and alliances with important complementors such as Bank One for financing. It remains to be seen whether this business model, which calls for a small markup of $50 to $200 on each car sold, will hold in the face of competition and increasing consumer nonchalance about the Internet channel.

What is clear is that CarsDirect.com and its competitors have dramatically changed customer expectations for some important segments by digitizing the experience. The proportion of people buying their cars entirely on the Internet has grown from 2.7 percent in 1999 to 4.7 percent in 2000. International Data Corporation forecast that 7 to 8 percent of sales will be completed online in 2004. An even more interesting change has been the use of online sources for research. Roughly 40 percent of prospective car buyers used the Internet for such purposes in 1999, 54 percent in 2000, and an estimated 60 percent this year.

Example: Making Things Simpler by Eliminating Administrative Hassles.–Instead of replacing or eliminating links in the chain, digital technologies can also be used to make the customer experience faster, better, cheaper, or more convenient. In the employee supplemental benefits area, a series of providers, with names such as Eyefinity and BenefitMall.com, have developed services to simplify the administration of employee benefits.

A good example is Colonial Life & Accident Insurance Company, a subsidiary of UnumProvident Corporation. Colonial has focused on the problems employers have in administering supplemental insurance plans. Supplemental plans can be a headache for plan administrators because each employee has unique fund allocations and types of expenditures. Colonial created a special Web site targeted directly at addressing the work of plan administrators with its ColonialConnect for Plan Administrators. More than a thousand employers are now taking advantage of the site’s services.

Among the more popular services is EZ Billing, which reconciles corporate benefit bills online at no charge. The plan administrator e-mails Colonial an electronic file showing what payments (based on company records) have been made against the money employees have set aside to cover benefit expenses (usually pretax). Colonial then compares the deduction information to its records and informs the plan administrator of any discrepancies, eliminating a series of reconciliation tasks.

This process greatly reduces the time and hassle of manually reconciling paper invoices or (as had become common among customers) manually entering data to reconcile two incompatible computer systems. A side benefit of this innovation is that the electronic process also reduces errors when compared with manual billing.

Example: Help Customers Deal with Their Logistical Hassles.–Other companies have discovered the benefits of using digital technologies to make life easier for their customers. A powerful way to use digital technology, particularly for industrial customers, is to minimize the costs, risks, and time consumed by logistics. This has proved crucial in capital-intensive industries.

Occidental Petroleum has relied on digitization to help it compete with the far larger companies that dominate its businesses: oil and gas exploration and production, and chemicals. Its OxyChem subsidiary, for example, was the first in its industry to embrace the use of electronic technology to create a logistical advantage. It pioneered supply chain connectivity through the Envera network, in which networked trading partners can exchange key transaction data, including purchase orders, order acknowledgment, shipment notification, receipt notification, invoicing, and change orders. The network lowers demand uncertainty, reduces inventory on hand, improves product flow, and minimizes cost.

Prospecting Questions for Digitizing the Chain

Inspect each link in the chain. Can you find ways to deploy Internet, telecommunications, or information technology (IT) and thereby dramatically enhance your offering by

Replacing or combining links?

Improving links by making the customer experience better, cheaper, or more convenient?

Capturing and mining data about the market or about your service delivery?

Better managing your logistics?

Adding new links that customers will be willing to pay for? Creating new offerings from the information you now collect anyway?

Move #3: Make Some Links in the Consumption Chain Smarter

This technique of hunting for marketbusters involves looking at the links in a consumption chain and asking whether you can add value by making that link smarter. By “smarter,” we mean adding intelligent attributes such as recognition, responsiveness, interactivity, or situation-specific calculations to the link. The idea is that value comes from information that you convey to the customer at that link.

You can use any number of electronic technologies to make a link smarter, but smarter does not have to be synonymous with electronics. Gillette’s Duracell battery division, for example, figured out how to create a smarter battery by embedding technology that allows a customer to test the battery’s charge.

Example: Making Payments Easier Through RFID Technology.–Texas Instruments pioneered the use of electronic intelligence when it began commercialization of radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology. TI’s RFID tags can be found in such offerings as the ExxonMobil Speedpass, which allows consumers to pay for gas and other sundries without having to swipe a credit card or pay cash. The electronic tags, which can be hooked to a keychain or placed on a credit-card-like plastic card, are linked to a payment system customers have set up in advance, which charges a credit card or other account for the purchase. Mobil (before the merger with Exxon) reported that within the first year of operation, Speedpass-enabled gas stations captured up to 6 percent more market share compared with ordinary gas stations.

Prospecting Questions for Making Links Smarter

Inspect each major link in your consumption chain. Can you find ways of deploying digital intelligence at that link to make your offering

- More responsive?

- Less of a hassle?

- More informative?

- More fine-tuned?

- More user-friendly?

- More convenient?

and thereby dramatically enhance the quality or convenience of the links in your chain?

Can you use digital intelligence to create greater awareness of the benefits you offer at that link?

Can you use digital intelligence to tell you when a customer is at the trigger point for that link?

Move #4: Eliminate Time Delays in the Links of the Chain

Many customers are willing to trade off time for money. This source of marketbusting opportunities requires you to understand how much customer time you’re wasting and to develop offerings that eliminate this waste. Alternatively, you might find good ideas by changing the sequencing of events in a consumption chain to create more value.

Example: A Better Beer Experience. Consider an activity as prosaic as buying a beer in a sports stadium. In America, this involves walking to a vendor’s location, waiting in a long line, placing your order with one of the waitstaff, finally getting your beer (usually in an extremely annoying and insecure plastic cup with a flimsy lid), and finding your way back to your seat (“excuse me, sorry, excuse me, let me just pass, sorry”), hopefully before you missed anything exciting. Some stadium owners began to try to improve the experience by adding seat-based order takers, but these people added to expenses and didn’t really change the majority customer experience because, for the most part, they were stretched too thin to cover all potential customers.

Executives at Ameranth Wireless, a privately held company founded in 1996, saw an opportunity to help stadium customers make better use of their time. The company created a handheld digital device connected to a local network. With such devices in place, information can be shared within the network at extremely low cost. The initial application involved saving time by allowing patrons to order food right from their handheld devices in the stadium and have it delivered to their seats.

Ameranth has since expanded aggressively into numerous arenas in which remote connectivity changes the time spent at one or more links in a customer’s consumption experience. Primary client groups include restaurants, hotels, and hospitals, which use the devices to shorten the time between the customer’s request and its fulfillment. Restaurants, for example, can use the software to preorder drinks and appetizers for patrons even before they have been seated. Hotels can use the technology to provide room service and speed the delivery of valet-parked cars. Hospitals can process food and medicine orders for patients faster and more precisely.

Ameranth’s main product, 21st Century Restaurant software, is poised to become the industry standard for mobile wireless ordering and payment processing in restaurants. In some cases, saving time for diners also results in increased sales. Busy restaurants find that they can increase turnover by providing faster service, thus increasing the revenue they can earn per table.4

Example: Automating Nutritional Analysis to Save Time in Clinical Trials. Sometimes, saving time can translate into substantial cost savings. Tiny Princeton Multimedia Technologies Corporation develops software that helps nutritionists rapidly analyze patients’ diets and develop better ones. The company’s ProNutra software calculates and manages metabolic diet studies to eliminate paperwork and provide rapid turnaround of information. ProNutra is being used by thirty research and medical centers, including the general clinical research centers of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and USDA human nutrition research centers. Other clients include Stanford, Yale, Harvard, Rockefeller University, and the University of Chicago.

Whereas many clients are using the software as part of weight management services for their customers, substantial financial returns are expected from its widespread deployment in pharmaceutical clinical trials. Because an important control variable for a clinical trial consists of monitoring patients’ nutrition intake, delays in this process can end up delaying an entire trial. According to founder Rick Weiss, “When you save a day of clinical trials, you are saving the company $1 million a day.”5

Prospecting Questions for Eliminating Time Delays

Inspect each major link in your consumption chain.

In some links, are there delays between the time demand occurs and the time delivery is completed?

Are these delays expensive, dangerous, or frustrating for customers? Are there ways to eliminate or shorten these delays? Are there ways to compensate for them?

Are there ways you can help your customers reduce delays for their customers?

Move #5: Monopolize a Trigger Event

A final opportunity for prospecting is to identify triggers in the chain and then find a way either to monopolize them or to be the first to notice when they occur. Have your team look for mechanisms to ensure that you are appropriately positioned to influence key decision makers at trigger points.

Example: Remote Monitoring of Elevators to Prevent Problems Before They Develop. For years, early identification of potential problems has been the core of the competition in the global business of maintaining building elevators. Then companies such as Otis (in the United States) and Kone (in Europe) invested heavily in technologies to provide early warnings of events that might trigger a maintenance call. Now these companies can either prevent the problem or arrive on-site to eradicate it.

Example: Getting the Right Advisor for Golf Cleats. A manufacturer of specialized golf cleats wrestled with the problem of determining the event that triggers customers’ awareness. The company’s cleats were designed to improve the golfer’s grip while minimizing any harm to the grass on the golf course, a distinct advantage over the metal cleats that were then standard.

The company could have approached large sporting goods retail stores, such as Sports Authority or Dick’s Sporting Goods. Or it could have approached specialty stores, online providers, or catalogs. The company decided, however, to think carefully about the trigger events that might lead a golfer to switch cleats. It concluded that among likely events would be the golfer’s first visit or two to a course that did not permit use of the metal cleats.

The next question was, who would be in a position to influence the prospective customer? The company decided to approach two sets of potential influencers. The first seemed obvious: golf pros at such courses. The second was far less obvious: the people who maintained the changing facilities and organized the caddies. The folks in place in a changing room or at the clubhouse have a lot of influence. The company found that these individuals had far more influence than was commonly recognized on all kinds of purchases in the multibillion golf equipment business. Access to the people who have access to the customer at a critical trigger point in the cleat-consumption experience proved essential to the launch of that business.

Example: Jiffy Lube Creates Self-awareness of Damaging Driving Behavior. Some companies are proactive in creating triggering events that might stand in their favor. The Jiffy Lube subsidiary of Pennzoil–Quaker State, for example, used research data to create a potential triggering event.

Jiffy Lube’s main business is providing convenient car maintenance services, such as oil changes. Working with Harris Interactive, Jiffy Lube discovered that most consumers were unaware of how tough many of them were on their cars. Some 86 percent of the 3,345 people surveyed initially rated themselves as normal drivers, even though they readily agreed that they drove their cars in the following ways: taking short trips, starting and driving without warm-up time, commuting in stop-and-go traffic, hauling heavy loads, pulling a trailer, driving in extreme heat or cold, and traveling in salty, coastal areas. More than 55 percent were surprised to discover that automakers would classify these behaviors as severely damaging. Jiffy Lube’s management publicized these findings during National Car Care Month, encouraging drivers to adopt more frequent maintenance procedures and thereby creating a trigger for the awareness link in the chain and hopefully increasing demand for the company’s maintenance services.

Prospecting Questions for Monopolizing a Trigger Event

Inspect each major trigger in your consumption chain.

How can you position your offering to monopolize a trigger? Can you be the first to know that a trigger event has occurred? Can your firm be the first in line or first in the customer’s mind when the triggering event occurs?

Can you create triggers that favor your firm or your offering?

Action Steps for Transforming the Customer’s Experience

The action steps that follow are meant to get you started on the concepts and processes discussed in this chapter. Feel free to elaborate or adapt them in a way that works best for your company.

Step 1: Identify your most critical customer segments. For each one, sketch out the primary links in its consumption chain. Get the information by interviewing as many people in your firm as possible who are directly in contact with customers. Ideally, also work directly with a sample of customers in each segment so that you get a visceral understanding of their needs.

Step 2: Identify the trigger events that precipitate customer movement from link to link (awareness, search, selection, and so on). Articulate how your organization identifies (or could identify) when a trigger event occurs.

Step 3: Consider the procedures you would need to alert you when the trigger is activated, and develop action plans to respond.

Step 4: Assemble a multifunctional team comprising all functions in your firm that interact with the customer in any way, and take the team members through the consumption chain. Try to identify any “quick hits” that would improve the chain for your customers and improve profits for you. Remember, if you make your customer’s experience at each link only a little better than that of the competition, it can be hard for customers to spot what you’re doing.

Step 5: Create a group to assess the potential for making a marketbusting move using the prospecting questions and the examples in this chapter. Make a rough assessment of the gains this move might provide you and how long the advantage would last.

Step 6: Consider the most promising of the ideas as you develop your strategy for the next round of competition.