7

Shift Your Outlook

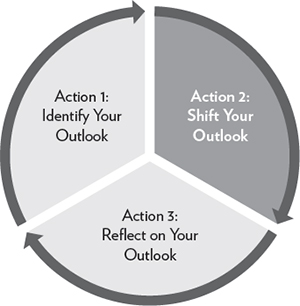

Shifting from suboptimal to optimal motivation—the second action in the skill of motivation, shown in figure 5—is inspiring!

Gratefully, people who have experienced shifting agreed to share their stories. Some agreed to let me represent them—and I sought feedback until they approved the accuracy of their experience. Others wrote their own stories, which are presented in their own words.

The shifting strategies revealed through the diversity of stories are designed to do one thing: illustrate the wealth of opportunities and resources and the variety of ways you can shift your motivational outlook on your own goal by creating choice, connection, and competence. I hope you’ll find important insights—and hopefully inspiration—in each example to help you shift your own motivation.

Notice how the questions to create choice, connection, and competence described in chapters three, four, and five have been used directly or adapted by people to help them shift their motivation and achieve their goals. As a reminder, these are the questions simplified to their essence:

1. Choice: What choices have I made and what choices can I still make?

2. Connection: How can I deepen connection through demonstrating genuine caring, aligning with my values and purpose, or contributing to the greater good?

3. Competence: How can I build competence by acknowledging my skills, developing expertise, and learning something new?

Figure 5 Action 2 in the skill of motivation—shift your outlook

As you follow the stories and examples for shifting, you might find it helpful to refer to the Spectrum of Motivation model in figure 4 (also shown on the inside cover of the book). The model is descriptive—it depicts the six motivational outlooks that reflect different types of suboptimal and optimal motivation. But it is also prescriptive—it shows how to shift between suboptimal and optimal outlooks according to the quality of your self-regulation.1

Shifting out of a Bad Habit

Roland was a lifelong smoker. He grew up in North Carolina and was the son of tobacco farmers. Smoking was a part of his life—he would have felt guilty if he didn’t smoke! Inevitably, his doctor gave him stern warnings to quit. He knew he should quit; the glaring warning on the cigarette package was a constant reminder. He tried, but since he was burdened with an imposed outlook, his efforts were futile. He chewed stop-smoking gum; he wore a stop-smoking patch. But he continued to smoke, got horrible nausea, spit out the gum, and pulled off the patch. He signed up for stop-smoking classes—and found himself grabbing a cigarette during the break. He quit (the class, not smoking). He heard about an acupuncture point on the ear that reduces cravings, so he had his ear pierced. Nothing worked.

One day, he was driving his car, smoking a cigarette, when his three-year-old daughter cried out from the backseat, “Daddy, please quit smoking. You’re killing me back here!” It took a moment for her outcry to sink in, but when it did, Roland experienced an immediate shift. He realized that smoking violated two of his primary values: his daughter’s health and being a good role model. He put out the cigarette and never smoked again.

Roland reports that to this day, he’s surprised how easy it was to stop smoking when he made a values choice that enabled him to shift from imposed motivation to aligned motivation. As he says, “I chose to love my daughter more than the cigarette.”

Roland created choice by realizing he had the power to smoke or not smoke. He created connection by recognizing that he loved his daughter more than anything else in the world—and being a good father was his most important role. He created competence by taking a step in being a good father, not to mention mastering a bad habit he’d tried to give up for years. When you create choice, connection, and competence, you also create courage—the courage to take action for the right reasons.

Roland’s story highlights a critical issue that surfaces if you want to shift from an imposed to an aligned motivational outlook. You cannot align to values if you don’t know what your values are—which raises the question, How do you know what you value?

What Do You Value?

To begin exploring your values, try this experiment:

1. Make a list of five to ten of your general life values. For example, family time, health and well-being, financial security, compassion for others.

2. Now, evaluate your stated values against two questions:

• How do you spend your money?

• How do you spend your time?

These two questions reveal the veracity of your stated values—they expose whether your values are fully functioning in your life or you talk a good game. For example:

![]() Your value statement is “I value work-life balance.” But the reality is, you spend sixty-five hours a week at work, often choosing business matters over family matters, and expect the same of your team members.

Your value statement is “I value work-life balance.” But the reality is, you spend sixty-five hours a week at work, often choosing business matters over family matters, and expect the same of your team members.

![]() Your value statement is “I value innovation.” But the reality is, you don’t spend time nurturing people’s creativity but rather applying pressure to drive results that shut down people’s creativity.

Your value statement is “I value innovation.” But the reality is, you don’t spend time nurturing people’s creativity but rather applying pressure to drive results that shut down people’s creativity.

![]() Your value statement is “I value compassion—I really care about people.” But the reality is, you donate less than 5 percent of your income to charitable causes, and you don’t donate time to help the less fortunate.

Your value statement is “I value compassion—I really care about people.” But the reality is, you donate less than 5 percent of your income to charitable causes, and you don’t donate time to help the less fortunate.

![]() Your value statement is “I value health.” But the reality is, you bought a gym membership and don’t use it.

Your value statement is “I value health.” But the reality is, you bought a gym membership and don’t use it.

Your answers disclose discrepancies between your espoused values (what you say you value) and your developed values (what you act on). Shifting from suboptimal to optimal motivation is nearly impossible if you are fooling yourself about what you value. How will you stick to a diet if you say you value health but really don’t? How will you donate to a worthy cause if you say you care about people less fortunate but really don’t?

Ironically, other people probably know more about your values than you do. People judge your values through your behavior and deeds. They notice how you spend your time and money. Research shows that people use their judgment of your values to conclude whether you are worthy of friendship, if you are a servant leader or a self-serving leader, and whether you can be trusted to act on what you say.2 If they see you as self-serving and untrustworthy, you are also seen as less effective—as a leader or an employee, a friend or partner.

My friend Deborah had a novel idea for evaluating a potential online dating candidate. She said, “I wish I could just ask him for his credit rating, the type of car he drives, and his BMI [body mass index].”

For Deborah, the young man’s credit rating could provide insight into his values concerning responsibility or financial security. The car he drives might point to values such as status or environmental concerns. His BMI could reveal values regarding health.

Even though Deborah was joking, she tapped into a powerful idea. Research shows that more than race, gender, or generation, the most important criterion for forging meaningful relationships is a match in values.3

But values hold the key to more than relationships. When you align your work-related goals to values, you attribute meaning to your work. When you align personal activities to values, you gain fulfillment in even the most mundane moments.

Comparing your espoused values with how you spend your money and time provides potent insight into your values. I encourage you to expand on the basic exercise to develop values for yourself. But you may also need to consider where your values come from in the first place.

If you are about to eat a bunch of french fries, you might think twice if you ask yourself what you value more than french fries—such as your health and well-being. If you are about to send a nasty email because you think someone made a boneheaded decision, you might hesitate if you ask yourself what you value more than being right—such as building the relationship rather than destroying it. If you are about to work overtime again, you might reconsider your priorities if you ask what you value more than the money or power you are working for—such as having dinner with your family or tucking your kids into bed.

Aligning with values to shift your motivation requires distinguishing between your espoused values—and your developed values. If you haven’t deeply thought about which of your values are espoused or developed, if you aren’t sure where your values come from, maybe it’s time to investigate.

Where Do Values Come From?

A developed value is an enduring belief that a particular end (your desired outcome) or means (your desired way of achieving your outcome) is more socially or individually preferable than another end or means. Notice a key word in the definition of a value: belief.

All your values come from underlying beliefs. So to understand where your values come from, begin with your beliefs. For example, when your beliefs are tied to an expert or authority—whether it’s a religious leader, the New York Times, or your parents—your beliefs are only as solid as that authority. When doubt is cast on the source of your beliefs, your derived beliefs are cast in doubt. Fallen role models and discredited authority figures often cause a values crisis—or should!

Challenging your beliefs—and especially the sources of your beliefs—has never been as important as it is in today’s world of fake news. The veracity of what we see and hear needs to be challenged, especially on social media. But on any newsstand in the world, you can see magazines and newspapers announcing bogus weddings, events that never happened, and conspiracy theories. We need to be vigilant about the sources of information that underlie the beliefs we form. Those beliefs, based on truth or not, result in the values that shape how we live, who we vote for, and decisions we make in every facet of our life.

To examine where the beliefs that shape your values come from, ask the following questions:

1. What are my values?

2. What beliefs underlie these values?

• When, where, and how did these beliefs arise?

• Are they based on my experience?

• Did they come from my parents? Family members? Friends? Social or religious groups? The military?

• Did they come from another source or authority?

• Have my beliefs been validated by others?

• Have I ever challenged my beliefs?

3. What might I believe if I let go of this belief and adopted another?

4. Would my values shift if I considered a different belief? If yes, then how?

You owe it to yourself to validate your values by first exploring the beliefs that spawned them.

The good news? Values are personal choices. Begin to explore the beliefs and values you currently hold. Proactively develop values you act on and cherish by making conscious choices about how you want to live your life. Then keep those values in mind as you shift your motivation to give up a bad habit or embrace a new habit for something—or someone—more important. Aligning goals with values is a powerful way to generate positive energy and experience optimal motivation.

A business associate I greatly admire tends to live her life making values-based decisions—such as moving to a different country to pursue meaningful work. Yet Judith discovered that as well-intentioned as we might be, sometimes our personalities or desires can make it a challenge to live according to our values with an aligned outlook.

Judith’s story not only demonstrates how to apply the skill of motivation but also reinforces how mastering your motivation takes you beyond achieving your goals. We have all fallen victim to social pressures that compromise our values and disconnect us from a more noble purpose. When you are mindful of being de-energized or energized by cruelty, unfair treatment of others, or other actions that run counter to your stated values and sense of purpose, you can identify your motivational outlook and take corrective action to shift your outlook by creating choice, connection, and competence.

What Does It Mean to Self-Actualize?

Mastering your motivation promotes living an authentic life with integrity. Mindfully creating choice, connection, and competence has proven to support the synthesis or integration of the desired behavior with other aspects of yourself—making you more wholly you. As a result, you are also more likely to find yourself not only creating choice, connection, and competence but living a life with a greater sense of well-being, vitality, and self-actualization.4

Speaking of self-actualization, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs comes up almost every time I teach or speak on motivation. Maslow posed the idea that people are motivated by satisfying lower-level needs such as food, water, shelter, and security before they can move on to being motivated by higher-level needs such as self-actualization.5 But the reality is, you can experience high-level motivation anytime and anywhere. Unlike Maslow’s needs, choice, connection, and competence are not hierarchical or sequential but foundational to all human beings and our capacity to thrive.6

The exciting message for you is that you can experience optimal motivation anytime and anywhere you choose by creating choice, connection, and competence. Self-actualization is a lofty aspiration, but it’s not a place you arrive, like the top of a mountain. Being self-actualized isn’t a one-time goal to be accomplished. Rather, self-actualization is a process of maximizing your abilities and resources to mindfully greet and find meaning in everyday challenges and opportunities. Self-actualization is a process for becoming—it’s never static. Mastering your motivation is the skill required for this process.

Phil has a zest for life that is unmatched. He is a minister, teacher, and entrepreneur who also has a passion for practicing the skill of motivation. He acknowledges that we all have issues that might keep us from being who we want to be—such as anger, impatience, jealousy, pessimism, indifference, resentment, and pride, just to name a few. Phil realized he had to shift his motivational outlook day to day to satisfy his need for choice, connection, and competence.

Phil’s credo defines Phil in a nutshell. I am pleased, but not surprised, to report that after living in the 95 percent during multiple operations and rigorous rehab, Phil is back to 100 percent as a life coach and flying across the country teaching workshops on topics he knows from firsthand experience, such as self leadership and trust.

Craft Your Own Credo

You might want to follow Phil’s lead by writing your own credo. The word credo is Latin for “I believe.” A personal credo is a statement of your core beliefs, or guiding principles, and your intentions for integrating them into your everyday life.

To create an optimally motivating credo to help you shift when you feel overwhelmed by a situation, external distractions, or pressure, include actions that will help create choice, connection, and competence. For example, consider statements such as these:

![]() I create choice:

I create choice:

• I choose how I wake up and live my life every day.

• My choices reflect my values and who I truly am.

![]() I create connection:

I create connection:

• What I do to others, I do to myself.

• My work is meaningful and contributes to a greater good.

![]() I create competence:

I create competence:

• I consciously improve my skills because doing what I do well is one of the ways I contribute to others.

• By learning something new each day, I spark wisdom, progress, and change.

You are never too young to consider your life credo. Ivan is working full-time to put himself through college. I think his story is a perfect example of how by creating choice, connection, and competence every day, optimal motivation becomes a conscious and deliberate act.

As well as anyone I know, Ivan reflects on his experience, learns lessons, and internalizes the lessons into a life stance. Talking to Ivan, I always come away from the conversation knowing more about him and myself, because his hunger for insight is contagious! His stories paint a picture of a young man creating a credo of proactively making choices, connecting choices to meaningful values, and building competence through experience. Perhaps developing your own credo can help you master your motivation and generate the positive energy to achieve your goals and live your dreams.

The Magical Combination

The psychological needs, choice, connection, and competence, can be measured individually, but they are deeply intertwined. For example, if your manager unfairly micromanages you and you don’t deal with it, choice is eroded because you’re being told what to do, how to do it, and when. Your connection to your boss is eroded because he appears oblivious to your needs. Your competence is eroded because your manager obviously doesn’t think you can handle your work without his intervention—and creating competence when you doubt your ability to do your job is nearly impossible.

Over her career, Brenda’s capacity to master the demands of her job had propelled her into a major leadership role in a prestigious company. Brenda’s story demonstrates when one of your needs is out of whack, the others are diminished, and so is your optimal motivation. But when choice, connection, and competence are combined, they work like magic.

Brenda discovered that shift can happen when you create choice, connection, and competence. But if shifting strategies haven’t worked in your case, don’t despair. Hold the hope of optimal motivation by taking the third action: reflect on your outlook.

Learn more about shifting your outlook by visiting the Master Your Motivation page at www.susanfowler.com.