CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 6

The Turnaround Challenge

“Get in there and stop the bleeding,” Debra Silverman was told. “Then you can figure out where we should take this business.” As the newly appointed general manager of InovaMed’s FemHealth business unit, Debra knew this was going to be a challenge. FemHealth had been launched three years earlier but had failed to gain much traction with its physician customers or to justify the substantial investments the parent company had made in the venture—and unacceptable losses were mounting. As a result, Debra’s predecessor, who had been the driving force behind the creation of FemHealth, had been let go. Now it was Debra’s job to clean up the mess.

Ohio-based InovaMed developed and manufactured medical devices and was organized into three divisions: cardiology, orthopedics, and surgical care. The latter group developed instruments and supplies for most common surgeries—sutures, scalpels, retractors, and the like. The surgical care division was the leader in its field, with strong market positions in most major product categories. Still, it was competing in relatively mature markets, and leaders in the division were aggressively scouting for potential areas of growth.

It was in this environment that Debra’s predecessor had presented a compelling idea for a new business unit, which would be part of surgical care, dedicated to supporting the office-based treatment of women’s health problems. The market was growing rapidly: there had been a worldwide rise in the population of women aged forty-five to fifty-five. And technological advancements had yielded minimally invasive approaches and procedures in health care that were eliminating the need for long hospital stays and costly inpatient care. In response to these trends, the number of health care facilities dedicated to outpatient care for women had risen, both in the United States and in some European countries.

As outlined in the business case drawn up by Debra’s predecessor, the FemHealth unit would supply surgical devices and other products needed for the office-based treatment of women’s health problems, focusing primarily on five categories of disease, including fertility, pelvic pain, and incontinence. Because these ailments were typically treated by obstetricians and gynecologists, FemHealth could then market a range of its products to these same customers, thereby achieving synergies through marketing, sales, and product servicing. The business plan had also called for the cross-pollination of products between the United States and the European Union. There was already a strong market in the United States, for instance, for the instruments used in less-invasive treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding, but not so much in Europe. Conversely, there was high demand for the instruments used to treat incontinence in Europe but less so in the United States. FemHealth planned to build on existing successes to create demand for technologies and products in other places.

The products and technologies involved in treating the target FemHealth conditions were not part of InovaMed’s core expertise. So the parent company entered into a series of acquisitions and licensing agreements to build FemHealth’s operations and R&D capabilities. The surgical care division was responsible for managing those functions, freeing up Debra’s predecessor to focus on marketing and sales. The senior team had also decided that most of FemHealth’s important support functions—including finance, HR, IT, and regulatory affairs—would be provided through shared-services agreements. As a result, the general manager of FemHealth had just five direct reports—two marketing directors, a sales director, an R&D liaison, and a person dedicated to setting up the ventures through which InovaMed marketed products outside the United States and the European Union.

Three years in, the business was in deep trouble. It had missed revenue targets for four straight quarters—partly because of poor forecasting but also because of unexpectedly intense competitive pressures in all five of the product/disease categories FemHealth had targeted. To counter this, many new-product-development initiatives had been launched, but most were behind schedule and over budget. FemHealth had also been buffeted by a product recall for an instrument to treat abnormal uterine bleeding, resulting in unfavorable scrutiny from regulators and the press. And it was struggling to make the cross-pollination strategy work; regulatory approvals of European products in the United States were proceeding much more slowly than anticipated. As a result of these setbacks, the staff was seriously demoralized.

Debra’s new boss, William Butler, had given Debra’s predecessor more time than was typical to fix the problems. He was used to dealing with larger, successful businesses, and he understood that it often took time for start-ups to reach critical mass. But when no obvious progress was being made, William had little choice but to fire the GM and hire someone who could turn things around.

William knew Debra well; she had a history of dealing effectively—some would say ruthlessly—with troubled businesses. Debra had started her career in R&D in surgical care’s wound care business, before switching to various managerial roles in sales and then marketing. After a successful stint as a marketing VP in InovaMed’s endoscopic instruments business, Debra had made the leap to country management—most recently leading a three-year turnaround of the company’s struggling business in Portugal. While the business challenges at FemHealth were broader in scope than in any of her previous assignments, the promotion greatly appealed to her: It was just the sort of “fixer-upper” she relished taking on.

The Turnaround Challenge

It’s essential that new leaders figure out the organizational-change challenge they’re facing (using the STARS model) and then tailor their personal approaches for making the necessary changes happen. In this chapter and the next two, I will explore what this means in depth, focusing on turnarounds in this chapter, realignments in chapter 7, and diverse collections of STARS situations in chapter 8.

Debra Silverman is clearly facing a turnaround situation at FemHealth. The organization is in crisis, and there is indisputable evidence (in the form of ongoing losses) that recent attempts to improve things just aren’t working. The staff is demoralized and has lost confidence in existing leadership. There’s a definite sense of urgency: no thoughtful person is going to argue that Debra should proceed incrementally. The faster she can figure out what’s going on, the quicker she can initiate corrective actions.

When it comes to turnarounds, speed is of the essence. That’s because a turnaround is a lot like the car whose engine is on fire: you immediately pull over and extinguish the flames. Then you take the car to the repair shop, rip out the motor, and replace it with a new one. In the business context, your initial actions as the new leader of a turnaround should be just as urgent: you immediately try to stabilize the business, preserving the “defendable core” so it will survive. Then you can shift your attention toward reworking the business, laying the foundation for growth.

Business Systems Analysis

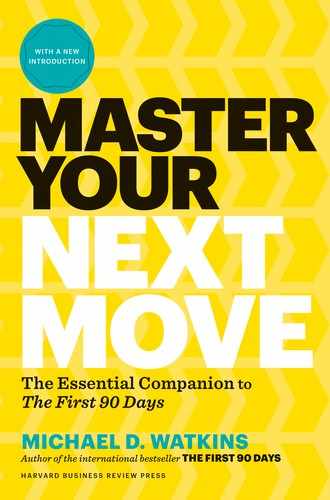

First stabilize, then transform—that should be your mantra as the leader of a turnaround situation. You’ll need to quickly diagnose the situation and then define the central organizational-change challenges. To accelerate the diagnostic process, it helps to have a view of the business as a dynamic system comprising interdependent elements that can also be analyzed individually. (See figure 6-1.) Specifically, you’ll need to focus your attention on these four important components of your organization’s business system:1

- External environment: The competitive and political challenges the business faces, as well as the expectations of important outside stakeholders.

- Internal environment: The organization’s climate and work culture.

- Business strategy: The mission, vision, goals, metrics, and incentives that provide overall direction for the business.

- Business architecture: The leadership team, skill sets, and core processes that are needed to realize the strategy.

FIGURE 6-1

The Business System Model

This graphic represents the key elements of a typical business unit. It highlights the discrete components that can be analyzed as well as the linkages among these elements. In general it is not possible to change one element of a business system without having an impact on others.

The first two can help you define the threats and opportunities your business faces; the second pair are the critical levers you can use to influence organizational performance. But these are interdependent elements, after all, so the business strategy helps to connect shareholders and other external parties to the organization. And the business architecture—aside from supporting the strategy—strongly influences the organization’s climate and work culture. Let’s take a closer look at each component—and at how Debra Silverman might tackle her turnaround challenge at FemHealth using the Business Systems Analysis framework.

The External Environment

At the time Debra took over FemHealth, the business was subject to intense pressures from competitors in each of the five major product/disease categories the company was targeting. It was also confronting strong political headwinds with its attempts to gain regulatory approvals for the launch and reimbursement of FemHealth products in the United States and Europe. Moreover, Debra’s room to maneuver was shaped by the expectations of outside stakeholders, including her boss and the senior team at InovaMed. A detailed overview of the FemHealth scenario, based on Debra’s initial diagnosis, is summarized in the box “Assessing the External Environment.”

The Internal Environment

As defined earlier, the internal environment encompasses climate and work culture. The organizational climate refers to how people feel about the business and their relationship to it. The work culture refers to the ways that people in an organization communicate, think, and act—patterns mostly grounded in their shared assumptions, values, and experiences. When these patterns are functional, they can result in high-level performance: people hit their targets, and then some. When these patterns are dysfunctional, they can sink morale and employee engagement. At FemHealth, for instance, some managers complained about the lack of accountability at the organization, as well as prevailing issues with conflict management—both significant areas of cultural concern for Debra. A detailed overview of the FemHealth scenario, based on Debra’s initial diagnosis, is summarized in the box “Assessing the Internal Environment.”

The Business Strategy

If, like Debra, you are charged with turning around a business, the right place to start is usually with a cold, hard look at the business strategy: the very fact that a complete corporate makeover is required is prima facie evidence that the existing strategy is inadequate. However, few aspects of business are more fraught with complexity than strategy creation and execution.

Experienced leaders intuitively understand the need to craft powerful, coherent road maps for their organizations—but surprisingly few can articulate what strategy is and what differentiates a good one from a bad one. Moreover, as leadership teams struggle to assess existing strategies and develop new ones, it’s all too easy for them to get mired in semantics: Are we talking about mission, or vision? Are we really debating strategic options, or just talking tactics? Should we devise a strategy for the business as a whole, or for specific functions such as marketing or R&D?

When it comes to defining good strategies, certain things are clear: They create value for customers and capture value for investors over the long term. They are powerful simplifications that, when communicated effectively, provide clarity, focus, and alignment across the organization. They leverage and enhance the organization’s core competencies. They respond to challenges and create opportunities in the external environment. And they are robust and adaptive, not brittle.

When the discussion turns to crafting good strategies, however, things get a little fuzzy. Is crafting a strategy the same as designing a business model? Should the strategy help determine how leaders achieve support for change and alignment throughout the organization? Does a good strategy also focus attention on how the business will learn and adapt to changing conditions? The answer to all three questions is yes. But leaders are seldom clear about which of these strategic conversations they’re actually having.

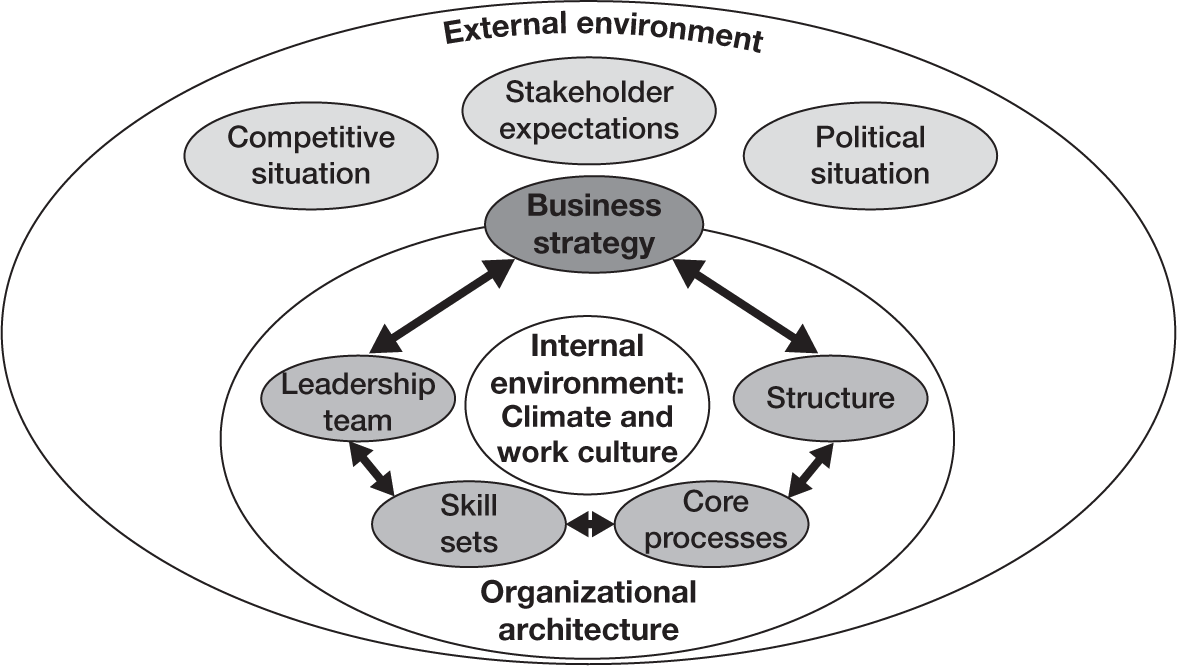

To succeed in your turnaround efforts, you’ll need to understand all three of the discrete dimensions involved with crafting a good business strategy. The central elements of this 3-D Business Strategy model, illustrated in figure 6-2, are as follows:2

- Designing (or redesigning) a business model that profitably exploits specific opportunities in the external environment and that can withstand related threats.

- Driving organizational alignment to ensure that employees at all levels of the organization are motivated to make decisions that are consistent with the business model and that will help the company achieve its goals.

- Dynamically adapting to changes in the external environment as well as proactively “shaping the game” through innovation and creative efforts to influence the political/regulatory environment.

FIGURE 6-2

3-D Business Strategy

This diagram illustrates the key elements of business strategy.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these critical dimensions of strategy.

Dimension 1: Designing (or Redesigning) the Business Model

The business model defines the core logic of the business—the rationale under which it will generate revenues, manage costs, and achieve profitable, long-term growth. Critical elements of the business model include:

- A definition of the mission. What is the overarching focus of the business? What will the business do (and not do) in terms of target customers, product and service offerings, and value propositions?

- A true understanding of the business’s sustainable sources of bargaining power. How will the organization develop and sustain its ability to capture value in its dealings with customers and suppliers? How will it go about protecting its interests in interactions with policy makers, regulators, NGOs, and other nonbusiness actors?

- A comprehensive inventory of core capabilities. In what areas must the business excel in order to support the chosen mission and sustain key sources of bargaining power? Which tasks or processes does the business handle well internally, and which should it purchase or outsource?

These elements of the business model generally reinforce one another: a clear mission definition translates into accurate decisions about which investments to make in which core capabilities—all of which supports the central focus of the organization. Likewise, making the right investments in core capabilities can help the business to develop robust sources of bargaining power—for example, economies of scale, strong brands, and protectable intellectual property.

Indeed, as part of business-model redevelopment, it’s imperative for transitioning leaders to start off by clarifying the mission—understanding that it’s a stepping-stone toward refocusing the organization in the long term. This can be an important early win for new leaders: clarity about the mission begets clarity about the sources of bargaining power and core capabilities. This, in turn, facilitates the development of the second and third dimensions of business strategy: driving organizational alignment and dynamically adopting to environmental shifts.

To clarify the mission and redesign the business model, you and your senior team should ask yourselves a series of guiding questions: Which customers will we serve (and not serve)? Which products and services will we offer (and not offer)? With whom will we compete (and not compete)? What value propositions will we offer (and not offer)? And, finally, what kind of trade-offs will we need to make, and what are the implications of making those compromises? These questions impose a sort of discipline on the group and can immunize the business against “mission creep,” or trying to be all things to all people. If there’s a lack of strategic focus within the business, the negative effects will almost inevitably spill over to other components of the business system—as a result, the business may be hobbled in the external environment which, unsurprisingly, can contribute to a poor climate and work culture inside the organization.

To successfully turn things around at FemHealth, Debra must start by asking some hard questions about the mission and the business model. Since the company’s inception, everything has been a priority—which means nothing has been. In particular, the business has been focused on too many disease categories to get sufficient focus. Without a central focus, FemHealth’s leadership team hasn’t been able to make the hard resource-allocation decisions necessary to establish a center of gravity for the venture. And because there is a lack of synergies among the organization’s product/disease categories—that is, they don’t involve selling to the same customers or leveraging the same technologies—FemHealth hasn’t been able to leverage its portfolio of surgical instruments and devices to build up bargaining power with customers and suppliers. Put simply, there hasn’t been a clearly articulated rationale for why the various parts of the business belong together.

Debra needs to refocus the business on two or three product/disease categories, selecting a mix that both generates cash and demonstrates significant growth potential. This product mix should also reflect real, not imagined or hoped-for, synergies—common customers, marketing channels, technology platforms, and the like. The rest of the product probably should be divested. If FemHealth lacks critical mass in its chosen product/disease categories, then Debra might want to consider additional targeted acquisitions or licensing deals.

The business model provides the basis for articulating the strategic goals, or A-list priorities, for the business. This involves being realistic about the state of the business and asking yourself: Among all the key performance indicators—revenues, costs, cash flow, and so on—which are the most critical targets to hit? And which metrics will we use to gauge our progress in achieving these top objectives?

For each critical process or quality indicator, you’ll then want to establish your means of tracking performance. Structured methodologies such as the Kaplan/Norton Balanced Scorecard can be a great resource in this regard.3 Indeed, it often helps to create a graphical representation of performance—for instance, a dashboard using conventional green-yellow-red color codes to highlight process or performance improvements, stagnation, or failures. These compact visual aids can make it easy to both communicate the A-list priorities to the organization and monitor the team’s march toward achieving these goals.

Moreover, cascading high-level goals in this way inevitably triggers additional thinking from employees about focus and priorities: Given the overall revenue goal, what should the contribution of each product be? Given the overall cost-reduction goal, which areas should we target for cutting? And so on.

Finally, the scorecards and dashboards can also help generate explicit discussions about any fundamental trade-offs that need to be made in the business—for instance, “If we do X, we’ll have to do Y, and we should acknowledge that up front.” These discussions should obviously be informed by and consistent with the decisions the team made about the business model: what the customer value proposition is and which core capabilities the company needs to excel in. These conversations should also be baked into the organization’s operating goals, as I discuss in the next section.

Dimension 2: Driving Organizational Alignment

You’ve redesigned the business model and defined goals and scorecards. The second step in the strategy-development process is to ensure that people throughout the organization behave in ways that are consistent with and support the model and the goals. As shown in the 3-D Business Strategy model, there are three primary levers for creating such alignment: a comprehensive operating framework, a well-considered incentive system, and a strong vision.

How do people throughout the business know how to make the right decisions? The operating framework provides detailed guidance for what employees should do in order to support the business model and the achievement of critical goals. It establishes the “wiring” by defining who gets to make which decisions and provides guiding principles for how those decisions should be made. It encompasses your business’s standard operating procedures, key business rhythms, project management protocols, and crisis management routines. It also includes associated disciplines such as your organization’s planning and budgeting systems. Whether it is explicitly written down or just a set of tacit understandings, the operating framework is the shared “playbook” that provides people with guidance on how to coordinate their actions.

Given that they know how to make the right decisions, why should they do so? The incentive system provides a core rationale for why people should want to act in productive ways. It obviously should include an appropriate mix of fixed and performance-based bonuses, individual and group rewards, and monetary and nonmonetary perks. Critically, however, the chosen mix should be directly correlated to the business’s defined goals and metrics and the behaviors necessary for hitting those targets.

Finally, it’s no accident that, within the 3-D Business Strategy model, vision and mission sit at opposite ends: they truly are the beginning and end of a business strategy. The two are often confused, but it’s actually quite easy to distinguish them. Mission is about overarching goals and what will be achieved. When leaders proclaim, “We will take that hill,” it’s a mission statement. By contrast, a vision gives people a reason to go the extra mile. It is a compelling picture of a desirable future that people are inspired to realize—as when leaders declare that, “by taking that hill, we will make the world safer for your children and grandchildren.” Indeed, the presence (or absence) of “inspirational” language can provide a convenient acid test for distinguishing between mission and vision.

Dimension 3: Dynamically Adapting

The third and final dimension of the 3-D Business Strategy framework is dynamically adapting to shifts in the external environment. As the old saw puts it, “plans never survive first contact with the enemy.” This does not mean that planning isn’t important; it’s critical. What it does mean is that a good business strategy must be robust in the face of shifts in the environment. Critically, it means that a sound strategy must enable the organization to rapidly identify and respond to environmental shifts.

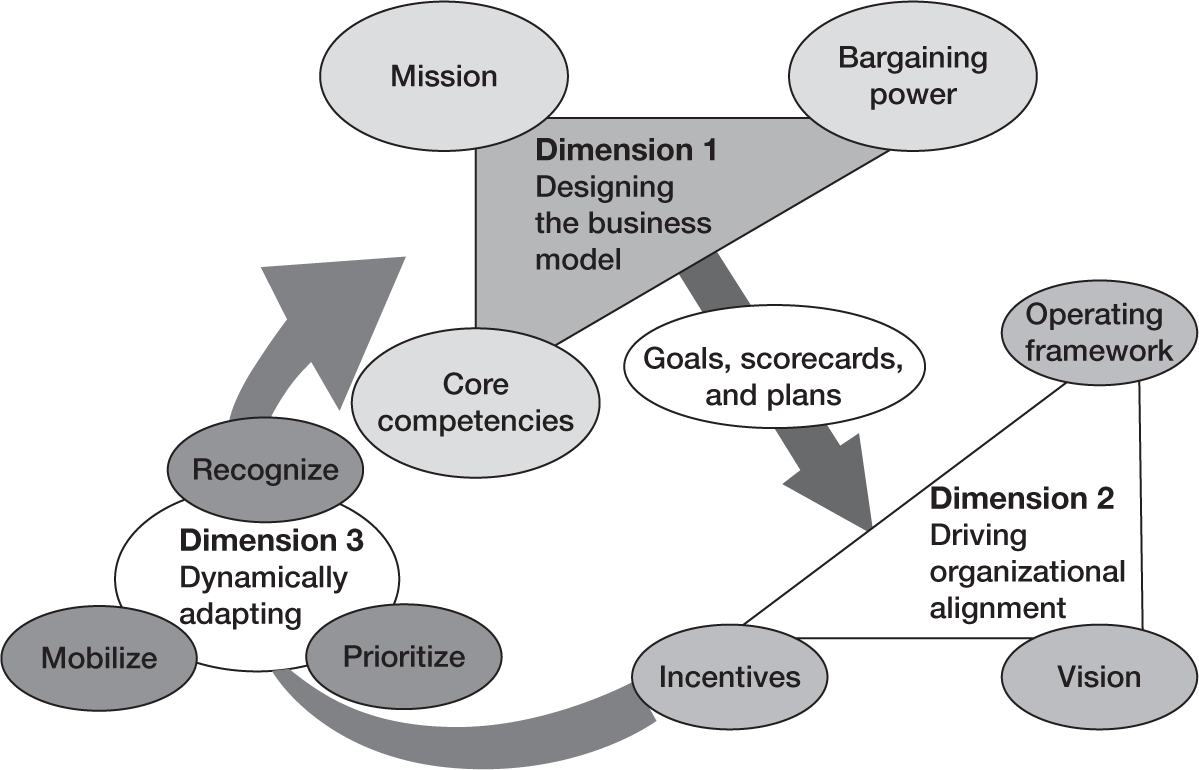

The point of departure for doing this is identifying emerging threats and opportunities, establishing priorities for responding to those threats and opportunities, and mobilizing to respond. Collectively these make up the business’s RPM (recognize-prioritize-mobilize) process, illustrated in figure 6-3. Related questions leaders like Debra should ask concern how (and how fast in comparison to competition) the business identifies shifts in the environment. Is the business being predictably surprised? What mix of centralized and distributed intelligence-gathering mechanisms are in place? How are the information process and priorities established? And what happens once a decision is made to respond?

FIGURE 6-3

The RPM Process

This diagram illustrates the cyclical process that businesses must put in place to recognize emerging threats and opportunities, establish priorities, and mobilize to respond.

The Organizational Architecture

Suppose, like Debra, you’re at the helm of a turnaround, you’ve labored to assess the external and internal environments, and you’ve survived the Herculean task of picking apart and redefining a failing strategy. To realize your plans for organizational change, however, you’ll need to focus on another piece of the business system: the organizational architecture, or the right foundation of resources, organized in productive ways. It comprises the following four elements:

- The business’s leadership team: Your direct and indirect reports, who collectively are responsible for setting direction, embodying important values and behaviors, executing plans, and getting results.

- The business’s skill sets: The types of skills and abilities, below the senior level, required to do the work of the organization and create desired results.

- The business’s organizational structure: The way employees are divided into units and functions, with associated decision-making rights, and the mechanisms for achieving integration across those silos (for example, project teams and liaison roles).

- The business’s core processes: The way information and materials flow through the organization to convert inputs to desired outputs.

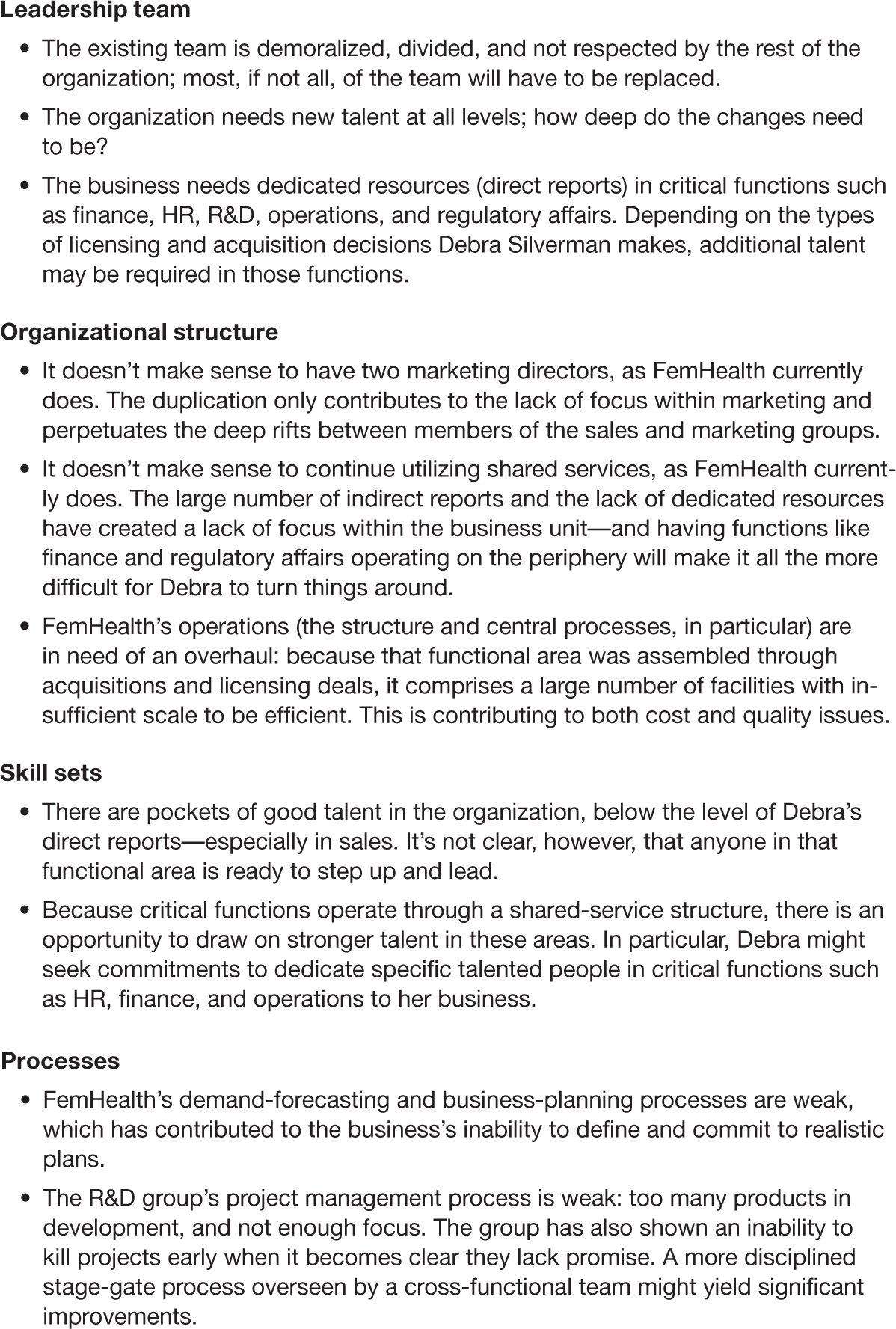

FemHealth had issues in all of these architectural areas, including problems with the quality of the leadership team, concerns about the structure of the sales and marketing organization, and weaknesses in the new-product-development process. A detailed overview of the FemHealth organizational architecture, based on Debra’s initial diagnosis, is summarized in figure 6-4.

FIGURE 6-4

Assessing the organizational architecture at FemHealth

While each of these elements of the organizational architecture can be analyzed independently, they must all fit within a coherent system: to execute the business strategy, the company needs the right leadership team, the right levels of talent placed in the right work groups, and efficient processes that produce the right outputs.

Therefore, an important piece of diagnostic work turnaround leaders like Debra Silverman must do early on is to assess whether misalignments among elements of the architecture are hobbling the business. Is FemHealth failing because the strategy is inadequate, or because the organization lacks the talent to implement the strategy properly? (As the details in the figure suggest, FemHealth’s existing strategy is deeply flawed.) Does the way FemHealth has organized people into work teams makes sense given the company’s goals? (The short answer is no—the shared-service structure ends up diffusing FemHealth’s overall focus and hinders its ability to leverage strong talents within and outside the company.)

Turnaround Checklist

- What are the key challenges in the external environment? What issues with customers and competitors have become particularly damaging to the business? Do the business’s problems flow in part from regulatory, political, or social issues?

- What is the existing business strategy? Why has it failed? Is it because the business model was inadequate? Because alignment was not driven down through the organization? Because the business was unable to adapt as quickly as its best competitors to shifts in the environment?

- How might the business be better focused? What should it do and not do? What are the sustainable sources of bargaining power? At what must the business excel?

- Is the operating framework adequate to align actions and decisions? Are incentives aligned with the business model and key goals? Is there a compelling vision of a desirable future?

- How effective is the business at recognizing emerging threats and opportunities? At establishing priorities for responding? At mobilizing rapidly? How might the RPM process be accelerated?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the existing architecture? What changes need to be made in the leadership team? In key skill sets? In the structure? In core processes?