CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 7

The Realignment Challenge

If Stefan Eisenberg knew anything, it was how to manage in times of crisis. After all, he’d overseen a relatively quick and successful turnaround of European manufacturing operations at Careco Devices, a multinational medical devices company. He was less sure, however, that this sort of approach would be effective in his new role at the firm.

Before joining Careco, Stefan, a hard-driving, no-nonsense executive, had spent fourteen years moving up the ranks in manufacturing at a leading automaker headquartered in southern Germany—starting as a productivity analyst and ending up as the general manager of the firm’s largest assembly plant. Senior-level slots at the car company were in short supply, and Stefan didn’t want to work for a competitor, so he decided to take his worldclass operations management expertise to a new company in a new industry.

After a series of interviews and a period of negotiation, Stefan joined Careco Devices as a senior vice president of manufacturing operations. The company was based in the United States but had operations in more than fifty countries and a long history in Europe. It boasted a regional structure, with distinct organizations in North America; South America; Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMEA); and the Asia-Pacific region. This was primarily because the company often needed to gain market-specific approvals for new products and certification of manufacturing processes. Stefan and his family relocated from southern Germany to Zurich, Switzerland, headquarters for Careco’s EMEA organization.

Stefan had originally been brought into Careco with a mandate: turn around manufacturing operations in Europe. He had moved decisively to restructure an organization that was broken because of the company’s overemphasis on growth through acquisition and its focus on country-level operations to the exclusion of other opportunities. Within a year, Stefan had centralized the most important manufacturing support functions, closed four of the least-efficient plants, shifted a big chunk of production to Eastern Europe, and reduced overall head count by almost 15 percent. These changes, painful though they were, began to bear fruit by the end of eighteen months, and operational efficiency continued to improve: three years after the changes had been rolled out, the company’s facilities were in the top 20 percent of benchmarked plants in Europe.

But no good deed goes unpunished: Stefan’s success in Europe led to his appointment as executive vice president of supply chain for Careco’s core North American operations, headquartered in New Jersey. The job was much bigger, combining manufacturing with strategic sourcing, outbound logistics, and customer service. With his appointment, the previously separate divisions were united in a single, end-to-end supply chain.

In contrast to the situation in Europe, Careco’s North American operations were not in immediate crisis—which Stefan began to realize was the essence of the problem. The long-successful organization had only recently shown signs of slipping. The previous year, industry benchmarks had placed the company’s manufacturing performance slightly below average in terms of overall efficiency and in the lower third in the crucial area of customer satisfaction with on-time delivery. Mediocre scores, to be sure, but nothing that screamed “turnaround.” In addition, the sorts of structural problems that had given Stefan low-hanging fruit to pick in Europe weren’t present in North American operations. For instance, there was already an appropriate balance of centralized and decentralized manufacturing support functions in the plants.

Stefan’s own assessment of the group, however, indicated that serious trouble was brewing. First, a close look at operations revealed a disturbing pattern of minor failures all along the supply chain—in planning, supplier integration, forecasting, and plant reliability. Initiatives had fallen between the silos, and when mistakes were made, there was more finger-pointing than troubleshooting going on—telltale signs of tension, even hostility, among units that had previously been stand-alone operations. Stefan believed there were better ways to integrate the four major pieces of the supply chain for which he was responsible.

Second, he noted the U.S. managers’ penchant for reveling in their ability to respond to full-blown crises rather than avoid problems in the first place. Problems would come up, but the so-called solutions the executives came up with merely addressed surface symptoms rather than root causes—which of course ensured that similar problems would reemerge in the future. The leaders who were most respected in this “culture of heroism” were those who vaulted into action, swords in hand, ready to charge into the breach. It had become clear to all that the organization highly valued individuals’ crisis-mode capabilities. As a result, people had learned to perpetuate and thrive on chaos.

Third, Stefan also felt that the executives relied too much on intuition, rather than impartial information, when making critical decisions, and that the North American organization’s information systems provided too little of the right kind of objective data. These shortcomings contributed, in Stefan’s view, to widespread and largely unfounded optimism about the organization’s future. This, in turn, fueled more firefighting: because executives reflexively viewed the glass as half full, they consistently failed to respond to early signs of trouble. They acted only when problems became large and undeniable.

Finally, Stefan recognized early on that he was saddled with various constraints to improving operational efficiency. For instance, the CEO of Careco Devices had publicly stated that the company would refrain from exporting U.S. jobs—either directly through plant construction or indirectly through outsourcing—to lowerwage nations for the next three years. As a result, none of the existing plants was an obvious candidate for closure; and while there were a few obvious opportunities for streamlining supply chain operations and reducing headcount, the resulting efficiency gains would be very modest.

Factoring in all this early information, Stefan concluded that North America’s performance problems had more to do with its culture than its strategy, structure, or systems. There was a strong commitment to teamwork and a lot of pride in what the organization had accomplished. But, particularly in manufacturing, there was just too much firefighting going on. Given what he’d accomplished in Europe, Stefan knew that people were expecting him to come into North American operations wielding a very big knife. But the transitioning executive wasn’t sure he wanted—or needed—to play according to that script.

The Realignment Challenge

Stefan’s story illustrates a common dilemma facing leaders who make inter- or intracompany moves: the importance of assessing and understanding the type of business situation they are inheriting. Specific to Stefan’s move to North American operations, is he facing a turnaround similar to the one he managed in Europe or a realignment scenario? Indeed, it will be nearly impossible for him to come up with an effective strategy for creating and supporting organizational change, and succeed in his new role, if he can’t recognize the important underlying differences between these two business situations—which can look remarkably similar on the surface.

The central difference is “sense of urgency.” As I noted in chapter 6, a turnaround situation is a lot like the car whose engine is on fire—the problem is obvious, and the driver’s response must be immediate and dramatic. That was the situation Stefan faced in Europe; urgent needs required urgent actions from him and his team. By contrast, a realignment situation is like the vehicle whose tires are slowly but inexorably losing air—the problem easily goes unnoticed over time, and the driver usually responds only after one or several wheels have gone flat. This is the scenario Stefan is facing in North America: the business problems are emerging slowly—so gradually, in fact, that they aren’t setting off many (or any) alarms.

Each transition scenario obviously demands very different change strategies from the new leader. In turnaround situations, for instance, the first priority for the transitioning executive is stabilization: restore some sense of equilibrium to the organization, its people, and its operations. Once that’s been achieved, the next steps are to preserve the remaining “defendable core” of the business—taking radical actions if necessary—and to identify opportunities for growth. But in realignments, the first order of business is education: the new leader must create a sense of urgency among people, many of whom won’t even recognize there is a problem. (See figure 7-1.)

As I discussed in chapter 6, the typical approach to change in turnarounds involves retooling the organization’s architecture, focusing first on strategy and structure and then on processes and skills; then creating a new, high-performance culture; and, finally, shifting employees’ attitudes from despair to hope. This is essentially what Stefan did in Europe. He closed plants, shifted production, and cut the workforce dramatically (a strategy shift). He also rapidly centralized important manufacturing functions in order to reduce fragmentation and cut costs (a structural shift).

Unfortunately, if Stefan tries to adopt a similar change strategy in Careco’s North American manufacturing operations, he could easily trigger the firm’s organizational immune system, prompting his boss, peers, and direct reports to summarily reject him and his ideas. (For more on organizational immunology, see chapter 4, “The Onboarding Challenge.”)

Particularly in an environment in which many people are in denial about the need for change, premature efforts to alter the organization’s strategy or tinker with its structure may be viewed as superficial or unnecessary—and will have a hard time gaining support. Consider that North American manufacturing operations aren’t experiencing any major capacity or productivity problems, so plant closures aren’t necessary (no need to change strategy). Critical manufacturing functions are already centralized and strong (no need to change structure). The real problems are in the quality of the company’s information systems and its somewhat pyromaniac culture—dynamics typical in many realignment situations. Indeed, organizational performance in North America may be showing signs of decline in part because previous leaders were prone to changing strategies and structures before dealing with other issues first.

Your decisions about which fundamental elements of the organization to tackle first, and which approach to use, are just the beginning, of course. In a realignment versus turnaround scenario, you’ll also have to define and secure early wins differently—the most important one being raising people’s awareness of the need for change—and you’ll need to handle personnel issues quite differently. For instance, to expeditiously turn around the European business, Stefan had to clean house at the top of the organization and bring in new senior talent from outside the organization. In North America, however, the leadership team he has inherited is reasonably strong—perhaps offering the transitioning leader a good case for promoting from within.

The Right Change Strategy for the Situation

Once you’re clear about the type of business situation you’ve inherited—turnaround or realignment—you can define the strategies you’ll employ to create the necessary changes in the organization. In realignment scenarios, it will be critical for you to mount a nuanced transformation effort—much more patient and subtle than the direct, dramatic actions that Stefan took in Europe and that were required in the turnaround situation described in chapter 6. The focus here has to be on, first, progressively raising awareness of problems; and, second, changing the attitudes and behaviors of a critical mass of people in the organization.

Raising Awareness

You’ll need to pierce through the denial and get everyone in the organization focused on preventing emerging problems from becoming much more serious. The following principles can help you alter the collective consciousness.

Emphasize facts over opinions. You can change the shade of your company’s culture from rose-colored to black and white simply by putting more emphasis on fact-based management and root-cause analysis. For instance, in Stefan’s early operational review meetings in North America, he and his team drilled down into issues where opinions were not backed up by facts. In those sessions, Stefan didn’t punish people for not having all the answers to his questions; instead, he firmly required that they go out and do some research to support or disprove their statements. His mantra was not “bring me answers, not problems”—a dangerous philosophy that can give team members a handy excuse for not raising tough issues. Rather, Stefan preached informed intervention: “Bring up issues early, and come prepared to talk about how you’ll diagnose root causes and begin to deal with them.”

Shift the focus outward. In realignments, it’s common for organizations to have become inwardly focused—relying solely on internal process performance benchmarks. To counter this, you’ll want to start bringing the outside world in, as much as possible. That might mean engaging in explicit benchmarking within your industry or even across industries. Stefan introduced explicit external benchmarking into the conversation at Careco’s North American manufacturing operations. He commissioned studies comparing the company’s manufacturing numbers and customer satisfaction scores with those across the industry. The studies revealed his organization was in the bottom quartile, which provided a big wake-up call.

Recruit others to help educate your people. As a new leader, you obviously need to force the people in the company or unit you’re joining to confront reality, but it’s always dangerous to be the sole source of pain in a group—you run the risk of becoming the main target for an attack from the organization’s immune system. One way to avoid this is to bring in outside voices—customers, suppliers, or even respected leaders from other parts of the business—to help say the things some people might not want to hear. Stefan greatly enhanced his efforts to raise organizational awareness about slack performance by bringing in impartial assessments from respected business consultants, drawing on expert voices from outside the company to help make his case.

Elevate the champions. More so than firms in need of a turnaround, companies requiring some sort of realignment typically still have a fairly strong pool of executive talent. So a powerful way to send a message to employees about the need for change is to elevate those people who exemplify the type of thinking you believe is necessary to lead the organization into the future. For instance, Stefan knew he’d have to make a few high-payoff changes within his team. Specifically, a few of the central positions in manufacturing required leaders with strong technical skills to support the systems changes he planned to make. Instead of looking outside for that expertise, however, Stefan promoted from within. People came to see that he wasn’t just focusing on the weaknesses of the business; he was also appreciative of its strengths.

Remove the blockers. Sometimes there is no substitute for the ritual sacrifice of an implacable opponent. In Stefan’s case, there was an influential manager in the North American supply chain operations who, despite Stefan’s best efforts, didn’t grasp the need for change; in fact, the manager’s inaction threatened to undermine Stefan’s plans and attempts to establish his leadership. That person’s departure sent a very important message to the rest of the organization.

Changing Attitudes and Behaviors

Research on human motivation has shown that the relationship between people’s attitudes and their behaviors is complex and bidirectional.1 Changes in attitudes do lead to persistent changes in behavior—but the reverse also is true, and often the effect is greater. That is, if you can get people to act differently, it will lead them to think differently. Research suggests that people are uncomfortable when there’s a mismatch between their actions and their beliefs, so they inevitably correct for it, aligning what they think with what they do. Therefore, it’s critical for new leaders in realignment situations to focus initially on altering behaviors, understanding that attitudes will change over time. The following principles can help.

Engage people in shared diagnosis. If you gather people to work on a problem, they go in with certain assumptions—namely, that there is a problem. If you gather people to generally explore or diagnose a business situation, they don’t feel forced to reach conclusions about possible solutions, or about the depth of transformation needed, until they are prepared to so do. I call this an “entanglement strategy.”2 You move people from point A to point B in a set of digestible steps rather than in a single leap. Stefan did this by setting up teams to focus on specific elements of performance across the supply chain rather than discrete “problem” areas. To lead the teams, he appointed people from each of the four operations segments whom he knew to be influential but who didn’t necessarily agree with him. As a result attention was focused on key handoffs between silos.

Change the metrics. People evaluate their performance according to a company’s or unit’s established metrics—for instance, number of products sold, amount of revenues earned, or number of satisfied customers. If you change those measures, you’ll inevitably change people’s behaviors (hence influencing their attitudes). The important point to note here, however, is that any change in metrics must be viewed by the team as necessary and legitimate. For instance, Stefan created a new, compact set of core metrics at Careco, shifting the emphasis from lagging indicators to leading ones. In this way, he was able to focus his team’s attention on overall supply-chain performance, rather than discrete, functional outcomes. And by shifting the group’s attention toward predictors of future problems, he ultimately affected how team members allocated their time.

Align incentives. If you reward people (through recognition, status, and advancement) for fighting fires, you shouldn’t be surprised if you end up with an organization of pyromaniacs. To get people more interested in preventing predictable surprises, Stefan had to get them moving in the same direction—providing positive incentives for avoiding fires and less-positive incentives for fighting them. This basic principle also extends to dealing with conflicts between units in your organization. You could easily attribute these tensions to mutual mistrust between groups or differences in personality. Most of these conflicts, however, are the result of differing incentives. To increase the peace among the supply chain units, and to reduce finger-pointing among team members, Stefan established “team incentives” directly linked to the new set of supply-chain metrics he had introduced. Initially, team members complained about being held accountable for others’ mistakes. Over time, however, they started helping one another. As their behaviors changed, so did their attitudes about the new setup of the supply-chain organization.

Build bridges from the past to the future. In realignment situations, where things haven’t completely broken down yet, it makes sense to build on the organization’s strengths in order to fix its weaknesses. This means building bridges (from where people are to where they need to be) rather than just jettisoning people and ideas. To kick-start the transformation process, for example, Stefan convened Careco’s top 150 supply chain managers in a series of sessions in which they collectively examined the company’s core systems, skills, and culture. They were challenged to identify strengths that could be leveraged and weaknesses that should be addressed. Among the cultural strengths the participants identified were deeply held values around both teamwork and responsiveness. The corresponding cultural weaknesses were tendencies to ignore problems until they became very serious and to engage in too much firefighting. Armed with this insight, Stefan and the managers were able to have progressive discussions about how to preserve the productive elements of the culture while uprooting the dysfunctional ones.

Secure and celebrate early wins. When you’re trying to change behaviors and attitudes in a realignment situation, it’s critical to achieve momentum—generating movement in promising directions and leveraging small gains to accomplish still more. So the instant you achieve some significant, measurable progress, you should declare (interim) victory and celebrate. This provides both visible acknowledgment that early efforts are beginning to bear fruit and an opportunity to recognize specific individual and team efforts that exemplify “right thinking.”

The Right Leadership Style for the Situation

The state your organization is in influences not just how you lead change efforts but also how you manage yourself—specifically, how you adapt your personal leadership style to the situation and build a team of people who complement your strengths and compensate for your weaknesses in the new context. This is particularly true when it comes to figuring out whether you are reflexively a “hero” or a “steward.”3

Heroes and Stewards

In organizational turnarounds, leaders are often dealing with people who are hungry for hope, vision, and direction—which necessitates a heroic style of leadership, charging against the enemy, sword in hand. People line up behind the hero in times of trouble and take direction. Clearly, this was the case for Stefan in Europe. A heroic leader by nature, he immediately took charge, set a course, and made some very painful calls. Because the outlook was bleak, people in the business were willing to act on his directives without offering much resistance.

Organizational realignments, by contrast, demand something from leaders more akin to stewardship—a more diplomatic and less ego-driven approach that entails building consensus around the need for change. Stewards are more patient and systematic than heroes in deciding which people, processes, and other resources to preserve and which to discard.

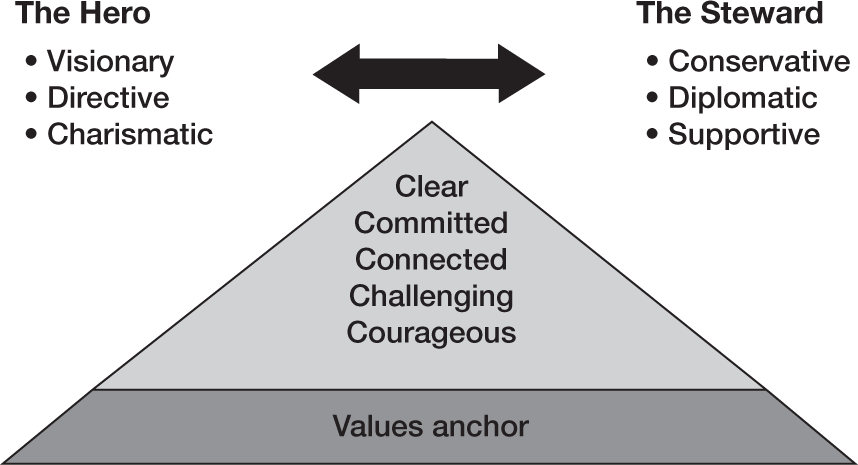

Accomplished heroes and stewards share many important attributes: they are typically grounded in basic values that people admire, such as a strong work ethic and a sense of fair play. Both types of leaders are perceived as committed to solving their organizations’ problems. They challenge others (and themselves) to achieve the highest possible performance. They clearly communicate what needs to be done, forge connections with the people who work with them, and courageously pursue needed change. (See the graphic summary in figure 7-2.)

FIGURE 7-2

Heroes and stewards

This graphic illustrates both the common elements of effective leadership and key elements that differ depending on the situation.

But, depending on context, heroes and stewards also need to exhibit fundamental differences in their approaches to leading change. What if Stefan approached his new role in North America as “Stefan the Knife,” and tried to set a new direction and make painful changes using the same heroic strategies that made him successful in Europe? Chances are great that his ideas (and even the man himself) would be rebuffed, particularly because he’s coming from the outside: a foreign organism that triggers a powerful reaction from the organization’s immune system. The result could be disabling, or even fatal, to his ambitions. So the natural hero must, when confronted with a realignment situation, tap into his inner steward. In his North American appointment, for instance, Stefan needed to make careful assessments of the situation, move more deliberately toward change, and lay the foundations for sustainable success.

Conversely, leaders who are more naturally stewards can struggle in turnaround situations. People in crisis are hungry for hope and direction, not necessarily for involvement and consensus. The situation usually calls for quick action, not systematic deliberations and discussions about shared visions and support. So the natural steward must, when confronted with a turnaround situation, tap into her inner hero—critically, while still preserving the basic management skills and approaches that have made her so effective as a leader.

Building Complementary Teams

While you’ll need to adapt elements of your leadership style to the business situation you face in your role, you obviously can’t be something you’re not. There are, after all, limits to leadership alchemy; and whether you are a hero or a steward, you won’t easily be able to tear down and then rebuild the foundations of your personal leadership style.

What you can adjust, at least to some degree, are particular aspects of your basic leadership approach. For instance, how do you learn in new situations? In the European turnaround situation, Stefan needed to rapidly assess the organization’s technical dimensions—its strategy, competitors, products, markets, and technologies—much as a consultant would. In the North American realignment situation, however, Stefan’s learning challenge was markedly different. Technical comprehension was still important, obviously, but cultural and political learning mattered more. Internal dynamics are usually one of the root causes when successful organizations begin to drift toward trouble—and getting people to acknowledge the need for change is much more a political challenge than a technical one. Particularly for a newcomer to the organization, as Stefan was, a deep understanding of the culture and politics is a prerequisite for leadership success—and even survival.

Moreover, you should seek out team members whose skills and styles complement your own. If you are reflexively a hero but the situation you are in demands more stewardship, you should identify those people in the organization for whom stewardship is more of a natural role. Indeed, at the core of all great leadership teams are two or three executives who exhibit the right mix of heroism and stewardship—taking the pressure off any one to play multiple roles. The steward helps to curb the worst impulses of the hero: impulsivity, micromanagement, and, in the extreme, narcissism. Meanwhile, the hero can counteract the steward’s tendencies toward risk aversion and perhaps too much consultation and consensus building.

The roles each leader will play are likely to be obvious, based on individuals’ tendencies, but the mix of styles necessary will change as the business situation does. In the crisis management phase of a turnaround, for instance, there is obviously a need for directive, heroic leadership. But once things have stabilized, the senior team will want to quickly cast its focus forward, toward tasks such as building leadership capacity in the organization—the work of stewards. Likewise, once the deliberations have been held and diagnoses discussed, every realignment scenario will have initiatives and programs that will demand bold and decisive action—work that calls out for a hero (or two).

Leveraging the STARS Framework

The STARS (start-up, turnaround, accelerated growth, realignment, and sustaining success) framework discussed in the introduction should be a standard component in any company’s change-management portfolio. By distinguishing among types of business situations, STARS helps leaders identify the kinds of change that are required and figure out how best to initiate the transformation process as they transition into new roles. Given the dynamism of the business environment, companies are experiencing more or less continuous change—some realignments, some turnarounds, some other flavors of transition. It behooves companies to equip new leaders with change processes and tools tailored to the different STARS situations.

The STARS model should also play a big role in how companies approach leadership assessment and team development. Simply put, firms should have a model for effective teamwork that is rooted in several realities. First, businesses are typically run by a core group of two or three people with complementary strengths. And second, the right mix of executives depends on the business situation. An important supporting plank for this is an assessment tool that gives insight into the team role preferences of leaders.

The STARS framework also can provide important insight into recruiting and onboarding challenges. External hires brought in to turn around a deeply troubled organization face quite different risks from those charged with realigning a business that is on the path to serious problems. Care must be taken, for example, not to set new hires up for failure by placing them in realignment situations and expecting them to create a sense of urgency unaided.

Finally, companies can incorporate the STARS framework into their talent management and succession-planning processes. Well-rounded business leaders have to be able to manage the range of STARS situations. It wouldn’t pay to produce, say, only turnaround specialists or realignment leaders. Most businesses display a mix of change situations; some elements are in turnaround, some in realignment (and some in accelerated growth and sustaining success). So it can be powerful to assess high-potential leaders in terms of their experience dealing with diverse STARS situations, and to use this information to identify critical talent gaps and opportunities to fill them.

Realignment Checklist

- Why has the organization begun to slip from sustaining success to realignment? Are key people in denial about the gathering storm? If so, why is this happening?

- Are the root causes of the problem about inadequate strategy or structure or, more likely, are they about the systems, skill sets, and culture of the organization?

- What aspects of the work culture support high performance and which undermine it? How have the negative aspects taken root and why have they been permitted to persist?

- What can you do to raise awareness of the need for change? Is there key data that can help make the case? Would a shift in metrics help? Are there influential voices outside the organization, such as customers, to whom people might listen? Would some shared diagnosis help?

- What kind of leader are you reflexively? A hero or a steward? What does the situation demand, more heroism or more stewardship?

- Given the needed mix of heroism and stewardship, how might you build a complementary team that will help you realign the organization?