CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 3

The Corporate Diplomacy Challenge

After just four months in her new job at Van Lear Foods, Irina Petrenko was deeply frustrated by the bureaucratic maneuvering going on at the corporate-headquarters level. “Where’s the support?” she wondered. An accomplished sales and marketing professional, Irina had risen through the country-management ranks of Van Lear, a leading international food company, to become the firm’s managing director (also known as “country manager”) in her native Ukraine. She was a hard-driving, results-oriented executive who had overseen dramatic growth in her territory.

Based on this success, Irina was promoted to managing director and assigned to turn around the company’s struggling operations in the Balkans. She thrived in this complex multinational environment, bringing in new talent, adjusting the product mix, changing the packaging to better match customers’ preferences and budgets, streamlining operations, and executing a targeted acquisition. Two and a half years later, the Balkans business was on track to achieving sustained double-digit growth.

Senior leadership at Van Lear recognized the potential executive talent they had in Irina and decided she needed some regional experience to round out her portfolio of accomplishments. So they appointed her regional vice president of marketing. In this new role, Irina would oversee marketing strategy, branding, and new product development for Van Lear’s country operations in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (the EMEA region). Her new home base was Van Lear’s EMEA headquarters, located near Geneva, Switzerland. Irina would report directly to Marjorie Aaron, the senior vice president of corporate marketing, who was based at the company’s U.S. headquarters. Irina also had a dotted-line reporting relationship with her former boss, Harald Emberger, the international vice president for EMEA operations, to whom all the country managers (all managing directors) reported.

Irina dug into her new role with her usual conviction and enthusiasm. She conducted a thorough review of current affairs, including a series of one-on-one conversations with managing directors across the EMEA region and with her former boss. She also traveled to the United States expressly to meet with her new boss and other important staff in Van Lear’s marketing and R&D groups.

Drawing upon those discussions, plus her own experiences in the field, Irina concluded that Van Lear’s most pressing problems—and opportunities—in the EMEA region lay in managing the tension between centralizing and decentralizing certain processes and decisions involved with new-product development. Specifically, to what degree should the company insist on consistent product formulation and packaging across the region and to what degree should it allow some flexibility for local variations? For example, what scope should a managing director in the Middle East have to adjust the recipe for one of Van Lear’s leading biscuit brands to appeal to local tastes?

Irina wasted no time putting together a presentation outlining the results of her initial assessment along with recommendations for improvements. Her suggestions included increasing centralization in some areas (for example, decisions concerning overall brand identity and positioning) and giving the managing directors more flexibility in others (such as the ability to make limited adjustments to recipes). Then she scheduled individual meetings with Marjorie and Harald, who both listened attentively and saw the merits of her approach. The next step, they advised, would be to brief the stakeholders who would be most affected by this organizational change—Van Lear’s corporate R&D and marketing executives in the United States and its country managers in the EMEA region.

Irina had been heartened by her bosses’ positive responses. Six weeks and several confounding meetings later, however, she felt like she was caught in quicksand. Following up on Marjorie’s mandate, she had scheduled a meeting with David Wallace, the corporate senior vice president of R&D, his staff, and important members of Van Lear’s corporate marketing team. She then flew to the United States to present to a group of more than thirty people, drawn from the main areas of R&D and marketing. Virtually every one of them had suggestions to offer, most of which would result in more centralization, not less. It also became clear to Irina during the course of the meeting—watching the body language and listening to the pointed comments—that there were significant tensions between corporate R&D and marketing. “I’ve walked into a political minefield,” she thought. Irina came away from the meeting with a greater appreciation for her predecessor, with whom she’d had frequent clashes when she was a country managing director. Clearly, he’d been grappling with a lot more at the headquarters level than she’d realized.

To her surprise, the conference call with the EMEA country managers—her old colleagues—didn’t go much better. They were, of course, more than happy to accept any ideas Irina had for creating additional flexibility. But when there was any mention of limits to their autonomy, the group rapidly closed ranks. One respected managing director, Rolf Eiklid, expressed concern that even if they did agree to some forms of centralization, the flexibility they received in return wouldn’t be enough to compensate for what they would be giving up. Because country managers had P&L responsibility for their territories and significant latitude to allocate local resources, Irina knew all too well that they could not be forced to fall in line.

The usually sure-footed Irina was thrown off her stride by this recent turn of events. She was used to operating with more authority and more urgency to get things done. The political maneuvering she had encountered at headquarters was dispiriting; so was the lack of support from her former colleagues. She was left wondering whether she had the patience and finesse to navigate the politics of her new regional role.

The Corporate Diplomacy Challenge

Irina Petrenko’s dilemma is a fairly common one for line leaders who move into positions where getting things done suddenly depends more on influence (your ability to build coalitions of support) rather than authority (your place in the hierarchy). The essential challenge is the same whether your new role involves navigating within a “matrix” organization (as was the case for Irina); negotiating with powerful external parties, such as government agencies; or leading a critical support function, such as HR or IT, but having other functions control critical budgets. If you want to achieve your objectives, you need to learn how to practice corporate diplomacy—effectively leveraging organizational alliances, networks, and other business relationships in order to get things done.

Failure to master this critical skill can lead to trouble: it’s easy for leaders who are used to wielding authority (and making decisions with their place in the hierarchy in mind) to get frustrated and attempt to impel people to do what they want. Instead of overcoming resistance, these leaders end up catalyzing reactive coalition building; they prompt potential opponents to build alliances—and reflexively close the ranks, as Irina’s former colleagues did. Indeed, the new leader can get caught in a deeply debilitating cycle in which her overreliance on authority yields increasing opposition, which then prompts even more inflexibility from the leader, and so on. Left unchecked, the result can be a series of increasingly polarizing conflicts between the new leader and important players in the organization. The new leader is particularly vulnerable in these battles; she still doesn’t understand how the organization works and hasn’t yet established alliances of her own, so these are fights she is unlikely to win.

Becoming an Effective Diplomat

What does it mean to be an effective corporate diplomat? Great diplomats proceed from the assumption that supportive alliances must be built in order to get anything serious done in organizations. They understand that opposition to change is likely, so they anticipate and develop strategies for surmounting it. They don’t expect to win over everyone; instead they focus on creating a critical mass of support. Most important, they devote as much energy to figuring out how to do things as they do to understanding what should be done. The starting point is to understand the importance of laying the foundation for alliances and defining key influence objectives.

Laying the Foundations for Alliances

Early on, transitioning leaders put a lot of effort into cultivating relationships in their new organizations, believing that these connections will pay off when it comes time to get things done—which is true. It’s wise for new leaders to build new relationships in anticipation of future needs. After all, you’d never want to be meeting your neighbors for the first time in the middle of the night while your house is burning down. But this operating philosophy underemphasizes an important point about organizational politics—namely, that there is a difference between building relationships and building alliances.

In a nutshell, alliances are explicit or implicit agreements between two or more parties to jointly pursue specific agendas. By contrast, relationships comprise a broader class of social interactions, including personal friendships, which may or may not involve agreements to pursue specific goals.

If relationships don’t necessarily imply alliances, the reverse also is true: effective corporate diplomats often build alliances with people with whom they have no significant ongoing relationships. Some alliances are founded on long-term shared interests that provide the basis for ongoing, supportive interactions; others are short-term arrangements that push specific agendas and then disband. Indeed, you may find yourself cooperating with people you usually disagree with—except, perhaps, when it comes to achieving a narrow goal involving a tiny slice of the business.

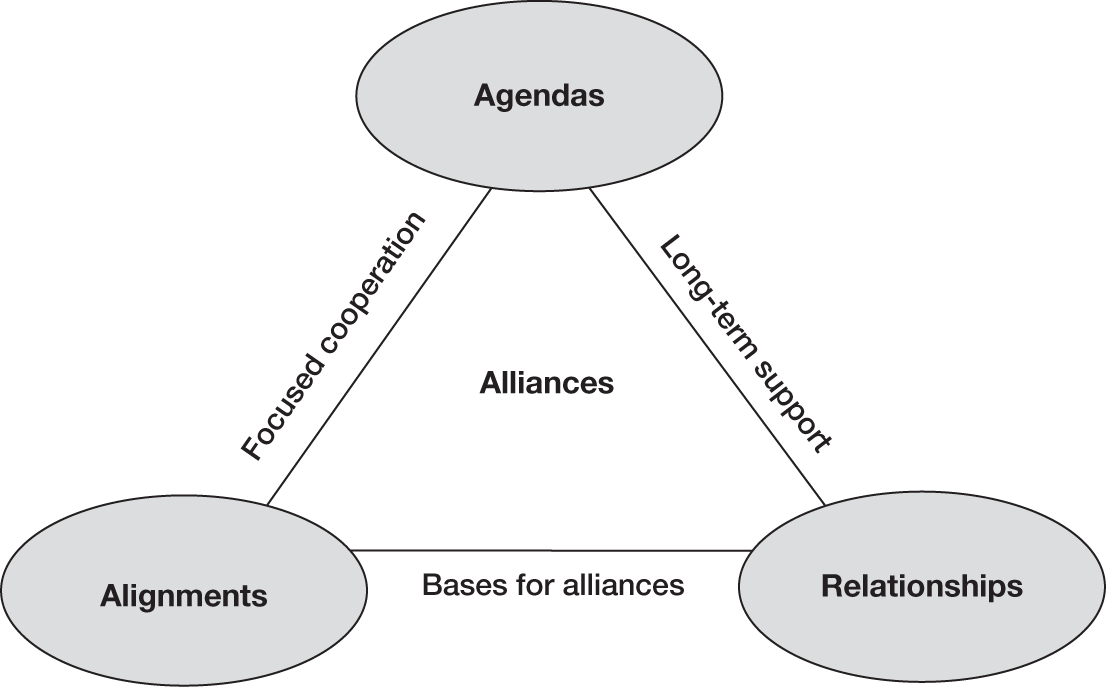

Leaders who, like Irina, are transitioning into positions where influence matters more than authority therefore need to focus as much on understanding others’ agendas and identifying potential alignments as they do on diagnosing business situations and defining solutions. As someone who was used to managing operations over which she had a lot of control, Irina naturally focused on the “technical” side of learning. She sought to understand the business, identify key issues, and propose solutions. Her experience, and perhaps her temperament, didn’t prepare her to focus on political learning. Your insights about how others’ agendas do (and do not) align with your own can be an essential point of departure for effective corporate diplomacy. (Figure 3-1 provides a graphic summary of these alliances.)

FIGURE 3-1

Agendas, alliances, and relationships

This diagram of alliances points out the foundation for creating strong ones: understanding the differences between business alliances and business relationships. A critical factor is the presence (or absence) of shared long- or short-term agendas.

Defining Your Influence Objectives

When viewed through the lens of corporate diplomacy, Irina’s challenge is a lot like that facing diplomats charged with negotiating a major treaty between, say, the United States and the European Union: the current status quo reflects a long-standing compromise between the two sides. It may be a flawed pact, but it’s more or less stable—until something or someone comes along seeking to create a new and different equilibrium.

So besides knowing how and why to build alliances and relationships—and understanding the difference between the two—it’s also essential for new leaders to be clear about their influence objectives: what do they hope to achieve?

Irina’s goal should be to try to fashion a grand bargain between her new (direct) and old (indirect) bosses and their respective organizations over how important product formulation and packaging decisions will be made. The corporate marketing and R&D organizations will naturally favor more centralization. The managing directors in the EMEA region will jump at opportunities for more decentralization. An agreement, if it can be found at all, will consist of a package of trades that both sides can support.

To secure such an agreement, Irina will have to orchestrate and facilitate a complex set of synchronized negotiations—both between and within the two opposing sides. It’s unlikely she’ll be able to achieve complete unanimity because some people will have far too much invested in the status quo. So she should focus instead on winning a critical mass of support for agreement on both sides.

Had Irina understood this from the start, she might have focused her initial efforts differently—not just on diagnosing problems and proposing rational solutions but also on understanding how her agenda fit into the broader political landscape on both sides of the Atlantic. She would not have just assumed that the strength of her case would carry the day; nor would she have felt compelled to win over every single stakeholder. A better way to begin would have been for her to identify the specific alliances she needed to build and how she could leverage existing networks of influencers in the organization. This process of mapping the influence landscape also might have helped her identify any potential restraining forces: What or who might stand in the way of people moving in her direction? How could she get those in opposition to finally say yes?

Mapping the Influence Landscape

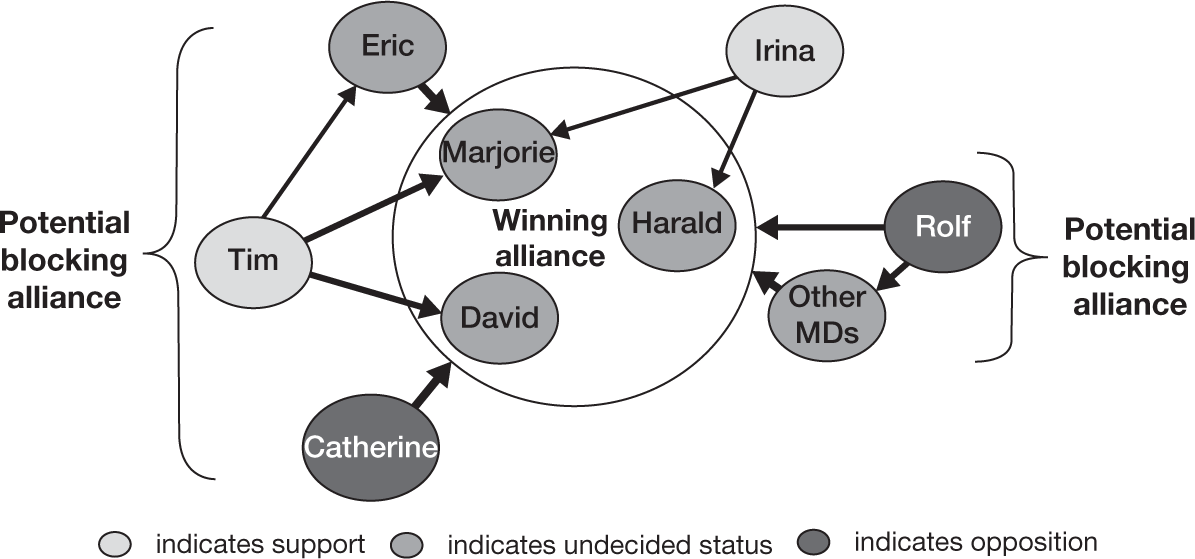

Armed with a deeper understanding of how alliances and relationships really work and the kinds of changes you’d eventually like to implement in the organization, you’re ready for the next step: finding the chief influencers and determining what you need them to do and when you need them to do it. Figure 3-2 provides a simple tool for capturing this information. Additionally, it’s often useful to summarize the results of such an analysis visually in an influence map, illustrated for Irina’s situation in figure 3-3.

FIGURE 3-2

Identifying influential players

Start to map your influence landscape by identifying influential players, what you need them to do, and when you need them to do it.

FIGURE 3-3

Irina’s influence map

This diagram summarizes relationships among key players in Irina’s situation. She is effectively a mediator between the corporate and EMEA organizations.

Winning and Blocking Alliances

A critical question to ask yourself is which players on either side of the situation are essential for building a winning alliance—a set of players who collectively have the influence necessary to shift the status quo.1 Irina Petrenko, for instance, needs to secure agreement for her proposals from Marjorie Aaron and David Wallace on the corporate side and from Harald Emberger on the EMEA side. But it is likely that they will be influenced to a significant degree by the opinions of others in their respective organizations. To achieve her objective, Irina will have to build winning alliances within the corporate R&D and marketing groups as well as in the EMEA organization.

Conversely, it also pays to think hard about potential blocking alliances—those who seek to preserve the status quo and have the influence to do it. (After all, any significant change is likely to create winners and losers.) Which influencers might band together to try to block progress, and why? Are there particular influential individuals on each side who are likely to be opposed? How might they organize and seek to impede the process? If you have a good sense of where opposing groups might spring up, you can blunt their strategies—or even prevent them from coalescing in the first place.

Mapping Influence Networks

To gain insight into potential winning and blocking alliances, it helps to look for patterns of influence (both formal and informal) across an organization—specifically, who defers to whom on a given set of issues, particularly on the issues of concern to you. These influence networks can play a huge role in determining whether change ultimately happens or not. They exist because formal authority is by no means the only source of power in organizations, and because people tend to defer to others’ opinions when it comes to important issues and decisions. Marjorie Aaron, for example, may defer to people in her organization with specific expertise on the impact of packaging changes on brand identity. The result is a set of channels for communication and persuasion that operate in parallel with the formal ones. Sometimes these informal channels support what the formal organization is trying to do; sometimes they subvert it.

There are several techniques new leaders can use to quickly gain more insight into these political dynamics. The first approach is to make some reasonable guesses about who the important players will be given the business issues you’re confronting; arrange some meetings; and then listen—actively and attentively. Ask lots of questions, phrased in ways that won’t trigger defensiveness. If you aren’t satisfied with an answer, ask the question two or three different ways during the discussion. Propose what-if scenarios as a way to elicit thoughtful advice from the people with whom you’re speaking.

The second strategy is to constantly scan for subtle signs of status and influence during meetings, hallway chats, and other interactions. Who speaks to whom about what? Who sits and stands where? Who defers to whom when certain topics are being discussed? When an issue is raised, where do people’s eyes track?

Over time, the patterns of influence will become clearer, and you’ll be able to identify those vital individuals who exert disproportionate influence because of their informal authority, expertise, or sheer force of personality. If you can convince these opinion leaders that your priorities and goals have merit, broader acceptance of your ideas is likely to follow. Additionally, you may be able to discern existing alliances—those groups of people who explicitly or implicitly band together to pursue specific goals or protect certain privileges. If these alliances support your agenda, you will gain leverage. If they oppose you, you may have no choice but to break them up or establish new ones.

Identifying Supporters, Opponents, and “Persuadables”

The work you’ve done to map influence networks in your organization can also help you to pinpoint potential supporters, opponents, and persuadables. Supporters could include anyone in the organization who shares your vision for the future, staffers who’ve been working for changes of their own, or other new leaders who haven’t yet become part of the status quo.

Opponents are those who are most likely to resist what you hope to accomplish. They may disagree with you for any number of reasons: They disagree with your business case for change. They’re comfortable with the status quo—perhaps too comfortable. They’re afraid the changes you’re proposing will deprive them of power. They’re afraid your agenda will negatively affect the people, processes, and cultural attributes they care about (the organization’s traditional definitions of value, for instance). And finally, they’re afraid of seeming or feeling incompetent if they have trouble adapting to the changes you’re proposing. If you understand your opponents’ reasons for railing against your initiatives, you’ll be better equipped to counter their arguments—and perhaps even turn them into supporters.

And speaking of conversions, don’t forget about the persuadables—those people in the organization who are indifferent to or undecided about your plans but who might be persuaded to throw their support your way if you can figure out where your mutual interests intersect.

An influence network diagram can help to summarize what you learn about these influential constituencies. Irina’s assessment of the patterns of influence at Van Lear Foods is summarized in figure 3-4.

FIGURE 3-4

Influence networks at Van Lear Foods

This diagram illustrates the key influence relationships that will shape decision making on the issues Irina Petrenko is trying to address in her organization.

As the center circle of the exhibit suggests, the critical decision makers at Van Lear—at least as it pertains to the issues Irina cares about—are two major players from the corporate arena, Marjorie Aaron and David Wallace, and the head of EMEA operations, Harald Emberger. Irina needs all three to agree with her change initiatives, so they jointly constitute a winning alliance.

But, as the arrows in the diagram indicate, these principal decision makers will also be influenced by people within their own organizations. (Wider arrows denote a greater degree of influence.) Marjorie Aaron will be strongly influenced by Eric McNulty, her vice president of marketing strategy, and Tim Marshall, a vice president in the corporate strategy group. David Wallace will be influenced by Catherine Clark, his vice president of new-product-development planning, and Tim Marshall. Harald Emberger will be influenced by the collective opinions of the country managers who report to him. But Rolf Eiklid, the longtime managing director of the Nordic countries, will be influential both in shaping Harald’s views and in influencing the other managing directors. The diagram also shows that Irina herself has significant influence on Harald and some on Marjorie.

The players’ support or opposition is indicated in the diagram—the darkest screen means opposition, light gray means support, and medium gray means undecided. According to the chart, Catherine is opposed to Irina’s proposals to shift the balance in centralization and decentralization of key decisions, Tim is in favor of changes, and Eric is undecided. Given that David is heavily influenced by Catherine, and Marjorie is moderately influenced by Eric, Catherine and Eric form a potential blocking alliance on the corporate side. Moreover, if the country managers side with Rolf, who is also opposed to Irina’s proposed changes, they could form a blocking alliance on the EMEA side. Note that, once again, she has to win a critical mass of support on both sides for overall agreement to occur.

Developing an Influence Strategy

Now that you’ve conducted a thorough analysis of the influence patterns in your organization, identified crucial players and alliances, and mapped out potential scenarios, it’s time to devise a strategy for leading through influence rather than authority—a critical factor of succeeding in your new role and creating the momentum for change.

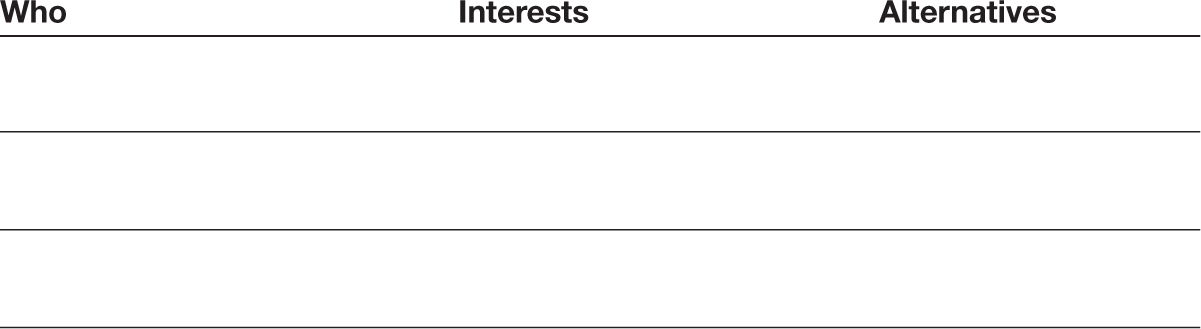

The first step is to understand how key players perceive their interests. Interests are what they care about. Key here is to understand what potential opponents like Rolf and Catherine are opposed to and why. Are there specific losses that could be avoided? Is there something they can be given—a valuable trade—that might help compensate? Now do the same analysis for potential supporters. What might they find attractive about what you are proposing? What concerns might they have that you could address up front?

Understanding people’s perceptions of their interests is only half the story, however. The other half is to understand how they perceive their alternatives. What are the options from which people believe they can choose? Critical here is to assess whether opponents like Catherine believe that resistance—overt or covert—can succeed in preserving the status quo. If so, then you have to find ways to reshape perceptions of alternatives so that sustaining the status quo is no longer a viable option. Once people perceive that some change is going to happen, the game shifts from outright opposition to a competition to influence what sort of change will occur. The implication for Irina is that she must convince the key decision makers—Marjorie, David, and Harald—that the current situation is not acceptable, that some change must take place. Figure 3-5 provides a simple tool for capturing this information.

FIGURE 3-5

Analyzing interests and alternatives

Use this table to assess how influential players are likely to perceive their interests (what they care about) and their alternatives (what choices they believe they have).

Armed with your assessment of interests and alternatives, you can think about how you will frame your argument. This means thinking through the rationale and data in support of your goals. It’s well worth the time to get the framing right. Indeed, if Irina can’t develop and communicate a compelling business case in support of her proposed changes, nothing else she does will have much impact. Your messages should take an appropriate tone, resonate with the interests of influential players, and, critically, shape how they see their options. Irina should, for example, explore what it would take to move Rolf from being opposed to at least being neutral and, ideally, supportive. Does he have specific concerns that she can address? Is there a set of trades that he would find attractive if implementation could be guaranteed? Are there ways of helping him advance other agendas he cares about in exchange for his support of Irina’s ideas?

Once you have thought through the framing, consider using the following techniques for creating the momentum for change: incrementalism, sequencing, and shuttle and summit diplomacy. All three work by shifting how key players perceive their alternatives.

Incrementalism. This approach involves moving people in desired directions in small steps and turning minor commitments into major ones over time. It is highly effective because each small step taken creates a new psychological reference point for deciding whether to take the next one. For instance, Irina could invite people to meet—initially just to explore the centralization-versus-flexibility “problem.” Over time, however, the group could analyze each of the issues involved. And finally, after they have deliberately walked through all major concerns, the participants could discuss some basic principles for what a good solution might look like.

Sequencing. This technique involves intentionally structuring the order and the way in which you approach various influencers in the organization.2 If you approach the right people first, you can set in motion a virtuous cycle of alliance building. Once you gain one respected ally, you will find it easier to recruit others—and your resource base will increase exponentially. With broader support, the likelihood increases that your agenda will succeed, making it easier still to recruit more supporters. Based on her assessment of patterns of influence at Van Lear, Irina should definitely meet first with corporate strategy VP Tim Marshall to solidify his support and arm him with additional information for persuading the likes of Marjorie, David, and Eric on the corporate side. Irina should meet with Eric second—after Tim has had a chance to bend the undecided executive’s ear.

Shuttle and summit diplomacy. This strategy involves convening combinations of one-on-one and group meetings to create the momentum for change. The critical point here is getting the mix right. One-on-one meetings are effective for getting the lay of the land—for instance, hearing people’s positions, shaping their views by providing new or extra information, or potentially negotiating side deals. But the participants in a serious negotiation often won’t be willing to make their final concessions and commitments unless they are sitting face-to-face with others—which is when summit meetings are particularly effective. A note of caution, however: if the process isn’t ripe—that is, if people haven’t had enough time to understand that they need to make concessions—such summit meetings can pave the way for blocking alliances to form or prompt players with veto power to withdraw from the room.

Ultimately Irina was unsuccessful in achieving the desired shifts in decision making. By the time she shifted her focus away from problem solving and toward political management, too much polarization had occurred. Seeing that the gap between the EMEA and headquarters had become unbridgeable, she wisely retreated and focused on working effectively within the existing framework. While disappointing, this was not fatal, and she learned a host of valuable lessons that made her much more effective in dealing with other cross-organizational challenges.

Corporate Diplomacy Checklist

- What are the critical alliances you need to build—both within your organization and externally—to advance your agenda?

- What agendas are other key players in the organization pursuing? Where might they align with yours and where might they come into conflict?

- What relationships could form the basis for long-term, broad-based alliances? Where might you be able to leverage shorter-term agreements to pursue specific objectives?

- How does influence operate in the organization? Who defers to whom on key issues of concern?

- Who is likely to support your agenda? Who is likely to oppose you? Who is persuadable? What are their interests and alternatives?

- What are the elements of an effective influence strategy? How should you frame your arguments? Might dynamic influence tools such as incrementalism and sequencing help?