CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Designing Companywide Transition-Acceleration Systems

Throughout the book I have explored the diverse tough transitions that leaders face, focusing on how to match strategy to the demands of specific situations. I also have offered some advice about what companies can do to accelerate the various types of transitions.

To conclude, however, it is essential to take a step back from the diversity of transitions and return to an exploration of their underlying unity. While each of the transition types has distinct features and demands, they all confront new leaders with the same fundamental imperatives: to diagnose the situation rapidly and well, to crystallize the organizational-change and personal adaptive challenges, to craft a plan that creates momentum, and to manage them for personal excellence.

What are the implications for how companies should accelerate key transitions? First, companies should recognize that effectiveness in transition acceleration is an essential element of enterprise risk management and a potential source of competitive advantage. Success in reducing the rate of personal leadership failure in transitions reduces the risk of organizational failure or damaging underperformance. Also, if you can help all the leaders in your organization make faster, better transitions, it will help you to be more nimble and responsive than your competitors.

Given this, a second implication is that companies should manage leadership-transition acceleration as they would any critical business process. Managing transition risk means putting in place the right structures and systems to accelerate everyone. It also means having the right metrics and incentives in place to assess transition risk and rigorously evaluate the impact of transition-acceleration systems in managing it.

A third and final implication is that it doesn’t make sense to design different systems to accelerate different types of transitions. When I see companies designing dedicated approaches to onboarding or promotion or international moves, I believe it to be a waste. Why? Because there is an underlying unity among the many distinct types of transitions. So it is both feasible and desirable for companies to design unified systems to accelerate everyone. Such systems consist of (1) a shared framework, (2) a set of tools and techniques that help leaders apply the framework appropriately given the type(s) of transitions they are experiencing, and (3) the right network of people playing key roles in support of the process.

By doing so, companies are able to institutionalize a common “language” for transition acceleration that everyone speaks. Leaders who learn it in one transition can apply it (with appropriate modification) in all the subsequent ones they experience. They also can appropriately support the many transitions that go on around them, as direct reports, peers, and bosses take new roles. The ultimate goal is to embed transition-acceleration thinking deep in the culture of the company.

Given this, how should companies approach designing comprehensive transition-acceleration “solutions”? In a decade of work with leading companies, I’ve developed a robust set of “design principles” that can be applied to build the right solution for your company.

1. Deliver transition support just-in-time

Transitions evolve through a series of predictable stages. New leaders begin their transitions with intensive diagnostic work. As they learn more and gain increasing clarity about the situation, they shift to defining strategic direction (mission, goals, strategy, and vision) for their organizations. As the intended direction becomes clearer, they are better able to make decisions about key organizational issues—structure, processes, talent, and team. In tandem with this, they can identify opportunities to secure early wins and begin to drive the process of change in their organizations.

The type of support that new leaders need therefore shifts in predictable ways as the transition process unfolds. Early on, support for diagnosis is key. Later, the focus of support should shift to defining strategic direction, laying the foundation for success, securing early wins, and so on. Critically, new leaders need to be offered transition support in digestible blocks. Once they are in their new roles, they rapidly get immersed in the flow of events and can devote only very limited time to learning, reflecting, and planning. If support is not delivered in small pieces, the new leader is unlikely to use it.

The design goal is to provide new leaders with the support they need, when they need it, throughout their transitions.

2. Leverage the time before entry

Transitions begin with selection or promotion, not when leaders formally enter their new positions. The time prior to entry is a priceless period during which new leaders can begin to learn about their organizations and plan their early days on the job. Upon formally entering their new organizations, new leaders are invariably swept up in the day-to-day demands of their offices.

Organizational transition-acceleration systems should therefore be designed to help new leaders get the maximum possible benefit during whatever preentry time is available to them. This means supporting new leaders’ learning processes by providing them with key documents and tools that help them to plan their early diagnostic activities. For executives it may be beneficial to have coaches engage in preentry diagnosis and create summary reports on the situation.

The design goal is to leverage the time prior to entry to help jump-start the learning process.

3. Create action-forcing events to propel the process forward

The fundamental paradox of transition acceleration is that leaders in transition often feel too busy to learn and plan their transitions. While they know that they should be tapping into available resources and devoting time to planning their transitions, the urgent demands of their new roles tend to crowd out this important work.

Although it helps to leverage the time before entry and to provide just-in-time support, transition processes also need to provide “action-forcing events.” These are key meetings with coaches or cohort events that bring leaders in transition into more reflective mind-sets.

The implication is that transition support should not be designed as a free-flowing process in which the leader sets the pace. It is better to create a series of focused “events”—coach meetings or cohort sessions—at critical stages. After undertaking some preentry diagnosis of the situation and helping the leader to engage in some self-assessment, for example, the coach and client are well positioned to have a highly productive “launch meeting.”

When transition coaching is provided it therefore is critical that the new leader and the coach connect early on in a focused and meaningful way. This is one reason it can be beneficial for coaches to engage in intensive preentry diagnosis: they have a precious resource—knowledge about the situation—that they can convey to the new leader. Their insight, offered in the critical early phases of the transition, can help to cement the coach-client relationship.

The design goal is to create a series of action-forcing events that help to drive the transition-acceleration process forward.

4. Provide additional, focused resources to support specific types of transitions

The First 90 Days principles can usefully be applied in all transition situations. However, the way the principles are applied and the specific priorities new leaders pursue vary significantly depending on the types of transitions they are experiencing. It therefore is often helpful to identify the most important types of transitions the company needs to support, and develop specific, targeted additional resources to support them.

In particular, there often are good reasons to provide new leaders with additional resources for dealing with two common types of transitions:

- Promotion. As discussed in chapter 1, when leaders are promoted they typically have to alter their approach to leadership in predictable ways. The competencies required for them to be successful at the new level may be quite different from what made them successful at their previous level. They also may be expected to play different roles, exhibit different behaviors, and engage with direct reports in different ways. So focused sets of resources that help newly promoted leaders “take it to a new level” help to accelerate these transitions.

- Onboarding. As discussed in chapter 4, when leaders join new organizations or move between units with distinct subcultures, they face major challenges in (1) learning about new cultures, (2) building the right sorts of relationships and supportive alliances, and (3) aligning expectation. Focused, accessible resources for helping them to understand what it take to “get things done” in their new organizations can help to reduce derailment and speed time to performance. In working with one global health care client, for example, I developed a set of Harvard Business School–like case studies on the company history and culture, as well as overviews of key businesses.

This is not a full list of potential transition types. International moves, for example, are an important category for many companies. It simply provides a starting point for assessment.

The design goal is to identify the most important, distinct types of transitions to be supported and then (1) provide guidance for how the core frameworks and tools should be applied and (2) provide additional, targeted transition-support resources as appropriate.

5. Match delivery mode and extent of support to the level of the leader

If cost were not an issue, every transitioning leader would get intensive, highly personalized support. In an ideal world, a new leader would be assigned a transition coach who would undertake an independent diagnosis and brief the person on the results prior to entry. The coach would help the leader engage in self-assessment and identify key transition risk factors. The coach also would help support the diagnostic planning and goal-setting processes, assist with team assessment and alignment, gather feedback on how the leader was doing, and, of course, be available to the new leader as needed to talk through specific issues.

Because their impact on the business is so great, it may in fact make sense to provide very senior leaders with this level of transition support. But it doesn’t make economic sense to provide it to leaders at the director level, even if sufficient skilled coaching resources are available.

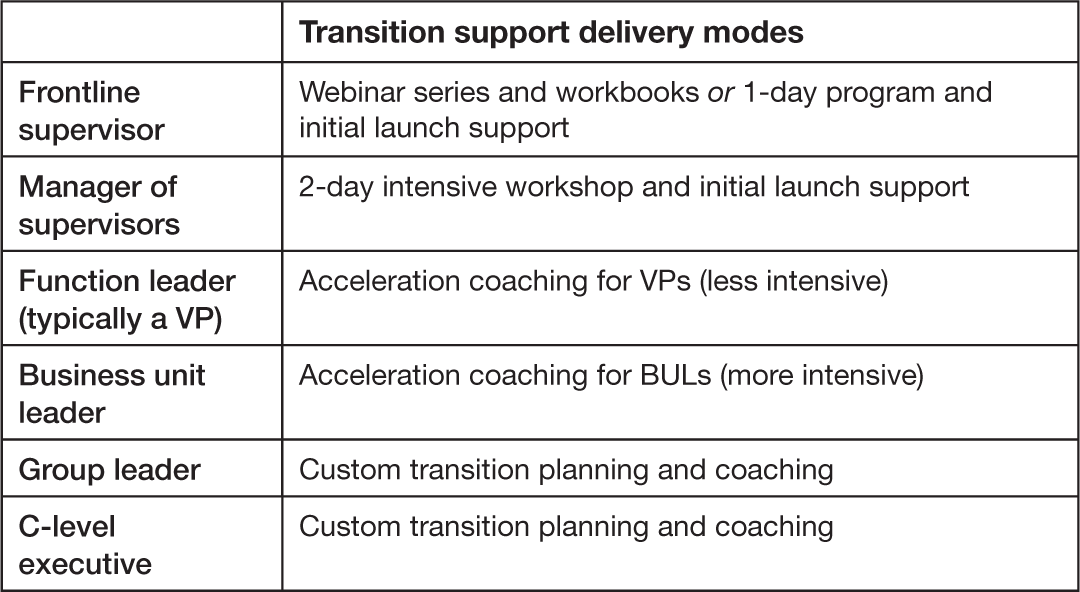

The solution is to (1) identify alternative modes through which to deliver transition support (for example, coaching versus cohort sessions versus webinars and e-learning), (2) assess their relative costs and benefits, and (3) match delivery modes and extent of support to key levels in the company’s leadership pipeline in order to maximize the return on investment (see figure C-1).

FIGURE C-1

Matching delivery mode to leadership pipeline level

The design goal is to provide support in ways that maximize the associated ROI given the level of the leader in transition.

6. Clarify roles and align the incentives of the key supporting players

Finally, for any given new leader, there typically are many people who potentially can impact the success of the transition. Key players may include bosses, peers, direct reports, HR generalists, coaches, and mentors. While primary responsibility for supporting a transition may be vested with one individual—typically a coach or HR generalist—it is important to think through the supportive roles that others could play and to identify ways to encourage them to do so.

The boss, for example, has an obvious stake in getting the new leader up to speed quickly, but also may be dealing with other pressing demands. So careful thought must be given to providing bosses and other key players with guidelines and tools that allow them to be highly focused and efficient in supporting their new direct reports. HR generalists likewise can provide invaluable support to leaders who are onboarding by helping them to navigate the new culture. But once again, they both need to know what to do and have incentives to do it.

The design goal is to get key players in the new leader’s “neighborhood” to provide the right amount of the right type of transition support.

In summary, the key goals in designing transition processes are to:

- Institutionalize a common language that bosses, direct reports, and peers can use to communicate about key transition issues.

- Provide new leaders with the support they need, when they need it, throughout their transitions.

- Leverage the time prior to entry to help jump-start the diagnostic process.

- Create a series of action-forcing events that help to drive the process forward.

- Identify the most important, distinct types of transitions to be supported and then (1) provide guidance for how the core frameworks and tools should be applied and (2) provide additional, targeted transition-support resources as appropriate.

- Provide support in ways that maximize the associated ROI given the level of the leader in transition.

- Get key players in the new leader’s “neighborhood” to provide the right amount of the right type of transition support.