CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 4

The Onboarding Challenge

The mandate David Jones had been given seemed clear enough: Bring some discipline and focus to a relatively young and fast-growing company that designed and manufactured wind turbines. But just a few months into his new job as COO of Energix, David was wondering if he’d been set up to fail.

It had seemed like the perfect opportunity for an ambitious executive with such strong leadership skills. After majoring in finance in college, David had joined an iconic Fortune 100 manufacturing firm that was both global and diversified. First in the supply chain unit, and later in R&D, David had risen steadily through the ranks to become vice president of new-product development for the company’s electrical distribution division.

David learned to lead in a company that was renowned for its management “bench strength” and its commitment to talent development. The culture leaned somewhat toward a command-and-control style of leadership, but people were still expected to speak their minds—and did. The company used state-of-the-art measurement systems to relentlessly weed out underperformers, but its reputation as a leadership factory made it relatively easy for the firm to recruit fresh talent. When the company needed to fill senior-level positions, it rarely hired from the outside. It didn’t have to.

The company had long been a leader in the adoption and refinement of the top management methodologies, including Total Quality Management, Lean Manufacturing, and Six Sigma. In fact, virtually everyone in the company had been trained in some elements of the latter; David was a black belt in Six Sigma. The result was an organization where people truly believed that “you can’t manage what you don’t measure.” They had internalized process management as though it were religion.

David’s superb quantitative skills and natural aptitude for systems thinking were important factors in his rapid ascent through the ranks—those and the aggressive nature he had honed as a linebacker for his high school and college football teams. He loved nothing more than tackling a problem and wrestling it to the ground. At well over six feet tall, David intimidated some. At the same time, he had been able to engender a strong sense of loyalty among his people because of the intensity with which he upheld the company’s commitment to leadership development.

Needless to say, the manufacturing company was fertile ground for corporate recruiters: personnel decisions tended to be of the “up or out” variety, and typically there was a surplus of good candidates for relatively few senior jobs. So, like most executives at the firm, David got calls from headhunters regularly. Sometimes he listened to their pitches; it couldn’t hurt to gauge his value in the outside job market, right? But he’d never really been tempted—until the opportunity to become chief operating officer of Energix came along.

Just six years old, Energix had been funded by Silicon Valley venture capitalists before going public. Capitalizing on increasing energy prices, Energix had established a strong and fast-growing position in wind turbine design and manufacturing.

The company was doing well; it had weathered the typical start-up transitions of going from two people to twenty to two hundred to two thousand and was now poised to become a major corporation. As a result, the CEO had told David more than once during recruitment and his final round of interviews that things had to change. “We need to become more disciplined,” the chief executive had said. “We’ve succeeded by staying focused and working as a team. We know each other, we trust each other, and we’ve come a long way together. But we need to be more systematic in how we do things, or we won’t be able to capitalize on and sustain our new size.”

The decision to appoint a COO was itself a big step for Energix. The CEO had never appointed a number two executive before. Previously he had relied on tight working relationships with the CFO and the heads of R&D and operations, all of whom were members of the company’s founding team. With the company’s growth, though, had come more internal tensions—and at a time when the CEO needed to focus more of his time on external relationships.

David liked the COO opportunity—quite a bit. On the surface, it appeared to be a near-perfect match for his skills. He would be offered an attractive compensation package linked to the company’s growth. He would have overall responsibility for internal operations, with broad scope to define his agenda. He understood that his first major task would be to identify, systematize, and improve the core processes of the organization—essentially laying the foundation for sustained growth for the company.

So David took the plunge and joined Energix, digging into the new job with his usual gusto. In the weeks before he formally took the role, he absorbed every piece of data he could about the company and its operations. He also conducted in-depth fact-finding interviews with all the members of Energix’s senior management committee (SMC) and other key people in new-product development, operations, and finance.

What emerged was a portrait of a company that had been run largely by the seat of its collective pants. Many important operational and financial processes were not well established; others weren’t sufficiently controlled. In new-product development alone, there were dozens of projects with inadequate specifications or insufficiently precise milestones and deliverables. The good news was that one critical project, Energix’s next-generation large turbine, was probably going to market in the next few months, but it was nearly a year behind schedule and way over budget. David came away from his fact-finding exercise wondering just what or who had held Energix together—and feeling more convinced than ever that he could push this company to the next level.

The problems began soon after David’s formal appointment. The SMC meetings started out frustrating and just got worse. The committee had decided that the CEO would continue to chair these meetings—just until David got established, they said. For his part, David, who was used to a high level of discipline in meetings, with clear agendas and actionable decisions made in tight time frames, found the committee members’ elliptical discussions and consensus-driven process agonizing. Particularly troubling to him was the lack of open discussion about pressing issues and the sense that commitments were being made through back channels. When David raised a sensitive or provocative issue with the SMC, or pressed others in the room for commitments to act, the committee members would either fall silent or recite a litany of reasons why things couldn’t be done a certain way. David approached the CEO with his concerns and was told it would probably just take more time for him to understand “the way we do things here.”

Two months in, with his patience frayed, David decided to simply focus on what he had been hired to do: revamp the processes to support the company’s growth. New-product development was his first target, for several reasons: his fact finding had pointed out numerous holes in that function, which touched many other parts of the company, and given his previous experience, R&D was something David understood quite well. So he convened a meeting of the heads of R&D, operations, and finance to discuss how to proceed. At that gathering, David presented a plan for setting up teams that would map out existing processes and conduct a thorough redesign effort. He also outlined the required resource commitments—for instance, assigning some strong people from R&D, operations, and finance to participate in the teams and hiring external consultants to support the analysis.

Given the conversations he’d had with the CEO during the recruiting process and the clear mandate he felt he’d been given, David was shocked by the stonewalling he encountered in the meeting. The attendees listened attentively but wouldn’t commit themselves or their people to David’s plan. Instead, they urged David to bring his plan before the whole SMC since it affected so many parts of the company and had the potential to be disruptive if not managed carefully. (He later learned that two of the participants had gone to the CEO soon after the meeting to register their concerns; David was “a bull in a china shop,” according to one. “We have to be careful not to upset some delicate balances as we get out the next-gen turbine,” said another. And both were of the firm opinion that “letting ‘Jones’ run things might not be the right way to go.”)

Even more troubling, as David tried to implement his ideas, he experienced a noticeable and worrisome chill in his relationship with the CEO. Previously, the CEO had reached out to him frequently. But increasingly, the onus was on David to initiate conversations. Their discussions had become both more formal and more formulaic, as the CEO increasingly stressed the importance of the launch of the next-generation turbine—indirectly suggesting that the product rollout should take precedence over efforts to improve processes. The CEO also deflected discussions about when David would begin to run his own internal operational meetings.

The Onboarding Challenge

As David Jones’s story suggests, joining an established business from the outside is never easy—the new leadership role is often ill defined, the organizational architecture will most likely be unfamiliar, and the politics are even more complex than usual. But such transitions are becoming increasingly common: because of their inabilities to build their own deep benches of talent, and given their ever-present mandates for global growth, more and more companies are looking outside for senior-level executives and then seeking effective ways to “onboard” them.

It follows, then, that firms that have spent a great deal of time and money to identify and recruit talent can ill afford for their newly hired executives to underperform or, even worse, become so frustrated that they decide to leave before they get a chance to gain traction. That’s where successful onboarding comes in. If new leaders are welcomed into a supportive environment—one that encourages them to realize personal and organizational aspirations—they’ll produce much more quickly and are more likely to stay around for a while.

But while the onboarding challenge is receiving more attention these days, many talented leaders still don’t believe their companies do a good job transitioning newly hired executives. A recent survey of senior HR executives I conducted through the IMD Business School in Lausanne, Switzerland, revealed that 54 percent of the respondents thought their companies did an inadequate job of executive onboarding.1

It’s also important to note that the onboarding challenge applies not just in those instances when new leaders are is transitioning between two different companies, as David Jones was, but also when he or she is moving between units of a company. In fact, my studies have shown that on average, moves between units in the same company are rated to be 70 percent as difficult as joining a new company. The primary reason is that units of the same company often have very different subcultures, the result of “bolt-on” acquisitions or the nature of work done within the unit.

Organizational Immunology

To increase their odds of success in their new roles, onboarding executives need to recognize that each company has its own distinct “immune system,” comprising the organization’s culture and political networks. Just as the function of the human immune system is to protect the body from foreign organisms, so is the organizational immune system ready to isolate and destroy outsiders who seek to introduce “bad” ideas.

To protect the human body, the immune system must demonstrate equal parts under- and over-reactivity. If it responds too weakly to warning signals, it may fail to mount an effective attack against a virus or may permit a damaged cell to grow into a cancerous tumor. But if the system overreacts, it will go after good things in the body, producing autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or multiple sclerosis.

Similarly, when the culture and political networks in organizations are working well, they prevent “bad thinking” and “bad people” from entering the building and doing damage. If the company’s immune system responds weakly to warning signs, bad leadership can infect the business and do tremendous damage. But if the system is working too well, even potentially good things coming from the outside can be destroyed. Specifically, the organizational system isolates and weakens the disruptive “agent”—in this case, David Jones—until he or she decides to leave. Even much-needed agents of change can succumb. In one Silicon Valley technology company I looked at, the success rate for outside hires was close to zero. And in a leading financial services firm I worked with, the gallows humor was, “When a new person is hired from the outside, a bullet gets fired at his head. The question is whether he can dodge it in time.”

It’s critical for transitioning executives to assume their new roles in ways that won’t trigger attacks from their organizations’ immune systems. Key is not to do things that cause you to be labeled as “dangerous.”

Thinking you have all the answers. David came in to Energix convinced that weak processes were the core problem and that he had the skills and knowledge to fix it. It was easy for him to reach this conclusion because process improvement was one of his core strengths, and he naturally interpreted the CEO’s description of the company’s need for “discipline” through this lens. He likewise viewed available data about the company in this light. So he came in expecting that everyone understood that this was “the problem” and agreed that he was there to fix it. Even if he was right, it didn’t matter. His naturally aggressive approach to leading change inevitably offended influential people, initiating an immunological reaction at Energix.

Wanting to bring in your own people. Think hard before you reflexively reach back to your old organization for talent, lest it contribute to triggering an immune reaction. (David didn’t fall into this trap, although he did try to bring in consultants that he formerly had worked with.) It is especially risky to “bring in your own people” if your new organization is a realignment or sustaining-success situation. If you are leading a turnaround and need to assemble a team quickly, it can make sense to hire capable people you know and trust. But in less-urgent situations, the reflex to bring in people you know can easily be interpreted to mean you’re dissatisfied with the level of talent in your new organization. If you need to replace people on your team, the first place to look is one level below. The second best option is to hire people from the outside—just not from your old organization(s). Once you’ve built up some credibility and trust in the new organization, it’s often all right to call previous colleagues—but beware of moving too quickly when hiring for critical positions.

Creating the impression that “there is no good here.” This is a related syndrome that can take hold during the early days of your transition, as you’re looking at the data and learning more about your new company. There is a natural tendency to focus on the problems—identifying them, prioritizing them, and drafting plans to fix them. But you can’t talk only about the problems you’ve observed and not about the organization’s strengths and accomplishments. It’s not enough that you recognize the positives; you have to demonstrate to others in the organization that you truly value these attributes. If you create the impression that you believe “there is no good here,” the organizational immune system will certainly kick in.

Ignoring the need to learn and adapt. Finally, a sure way to generate an immune attack is to behave in ways that are obviously countercultural and, critically, show little commitment to learning and adapting. Early on, you’re bound to act in ways that are culturally inconsistent, simply because you’re new to the environment. Usually, you’ll be forgiven for this. The danger comes when people think you have what political columnist George Will once described as “a learning curve as flat as Kansas.” David Jones, for instance, recognized that decisions were made differently at Energix than they were at his old company. But instead of trying to understand the culture, adapt to it, and eventually shape it, he got frustrated and tried to launch a frontal assault early on. The system, of course, wouldn’t allow it.

Indeed, once they’re activated, organizational immune systems are tough to beat—which is why you must build up tolerances instead, convincing the organization that you belong there even as you seek to make difficult changes. To do this, you’ll need to focus on three critical tasks very early in your tenure: adapting to the culture, making political connections, and aligning expectations.

Adapting to the Culture

Perhaps the most daunting challenge for transitioning executives is adapting to the unfamiliar cultures in their new companies or units. The first and most important step, then, is to understand what the culture is, at a macro level, and how it’s manifested in the particular organization or unit you’re joining. In doing this it helps to think of yourself as an anthropologist sent to study a newly discovered culture.

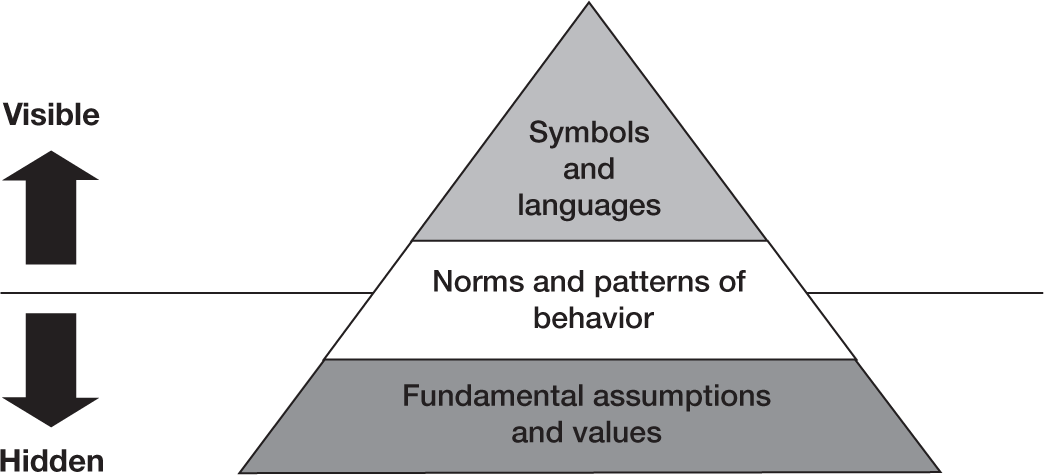

So what is culture? It’s a set of consistent patterns people follow for communicating, thinking, and acting, all grounded in their shared assumptions and values. The culture in any company will generally be multilayered, as illustrated in figure 4-1.2

FIGURE 4-1

Layers of culture

At the top of the pyramid are the surface elements of culture—the symbols, shared languages, and other things most visible to outsiders. Obvious symbols might include how people dress, how the office space is organized, how perks are distributed within certain work groups. Likewise, every organization typically has a shared language—a long list of acronyms, for instance, describing business units, products, processes, projects, and other elements of the company. At this level, it is relatively easy for newcomers to figure out how to fit in. If people at your level don’t wear plaid, then you shouldn’t either. If your peers and subordinates are accustomed to receiving certain perks, then it’s probably best for you, as a new leader, to adopt and maintain those benefits. And it’s essential that you invest in learning to speak the local patois early and completely—unless, of course, you’re intentionally trying to signal some sort of culture-change process.

Beneath the surface layer of symbols and language lies a deeper, less visible set of organizational norms and accepted patterns of behavior. These elements of culture include things like how people get support for important initiatives, how they win recognition for their accomplishments, and how they view meetings—are they seen as forums for discussion or rubber-stamp sessions? (See the box “Identifying Cultural Norms.”) These companywide norms and patterns are difficult to discern, and often become evident only after one has spent some time in a new environment—something David Jones should have acknowledged. He had learned to lead in a culture where everyone accepted the importance of having and following solid processes to get things done. But the culture at Energix was much more centered on relationships, a function of its status as a relatively young start-up. Even if it really was essential for him to focus the company on more and better processes, it was dangerous for him to assume from day one that the existing emphasis on relationships as a means for getting things done was dysfunctional—and to openly challenge such a crucial element of the culture.

And finally, underlying all corporate cultures are the fundamental assumptions that everyone in the company has about “the way the world works”—the shared values that infuse and reinforce all the other elements in the pyramid. A good example is the general beliefs people in the company have about the “right” way to distribute power based on position. Are executives in particular roles given lots of decision-making power from day one, or is the degree of authority a function of seniority? Or does the organization operate according to consensus, where the ability to persuade is key? Again, these elements of the culture are largely hidden from view and usually become clear only after you’ve spent time in the environment.

Once you have this “macro” understanding of the discrete elements of corporate culture, you can more easily determine what kind of corporate culture you’re stepping into and how it’s different from others you’ve experienced. This process needs to start early: you should be asking culture questions as part of the interview process, using the checklist to help formulate your queries. Be careful not to take everything you hear as gospel, however. Both sides will still be in the courtship phase, after all, and hiring executives understandably might be a little reluctant to pull back the curtain on the organization completely. If possible, try to schedule some chats with people who’ve left the company—on good terms and bad.

Once you’re inside the building, you’ll need to continue learning and adapting as quickly as possible. Inevitably, you’ll commit some “boundary violations,” acting in ways that aren’t consistent with mainstream behaviors. You can’t expect to fit in right away, and, in most companies, people won’t expect you to. But they will expect you to recognize your faux pas, do the appropriate things to recover, and recalibrate your behavior accordingly.

Clearly, then, it’s critical to familiarize yourself with the recognize-recover-recalibrate (R3) loop and work through each stage as quickly and efficiently as possible. Good resources in this regard are “cultural interpreters” in your new organization or unit. These are typically long-timers at the company who exemplify the culture but can also be reflective about it and, ultimately, provide useful guidance to the transitioning executive. (The same resources can and should be sought out when making international moves, as I discuss in chapter 5.) Finding all these traits in one individual can be difficult. But the search will be well worth it: these interpreters can be invaluable resources in helping you to recognize when you’ve overstepped cultural bounds, to make appropriate amends, and to reset expectations (your own and the company’s).

As you learn more about the culture, you’ll also need to consider the degree of adaptation versus change that will be necessary. The ratio will vary depending on where the company is in its life cycle and the particular business challenge it faces. (In chapters 6, 7, and 8, I talk more about the STARS framework that transitioning leaders can use to determine the context they’re operating in.) If you’re entering a turnaround situation, for instance, wholesale change will probably be on your agenda—including a fundamental reworking of the corporate culture. In these instances, the organizational immune system is already weakened, and new ideas are typically welcome. Harder, though, are realignment situations, where the changes may be more incremental—and where a dysfunctional culture can often be a significant part of the problem. In these instances, resistance to change will obviously be much greater.

Making Political Connections

As David Jones learned, a bit harshly it seems, it’s nearly impossible for onboarding executives to create any kind of momentum for organizational change when they aren’t plugged into the company’s political system—who has influence, who doesn’t, which relationships are most critical, and so on. The second imperative for transitioning leaders, then, is to identify key stakeholders and begin to forge productive working relationships with them. Here, too, there are two traps to avoid: focusing on vertical relationships and mistaking titles for authority.

Looking only “up and down.” There is a natural but dangerous tendency for onboarding leaders to focus too much on building vertical relationships early in their tenures—looking up to their bosses, down to their teams. As a result, the transitioning executives often neglect the lateral relationships they should be building and strengthening with peers, customers, and other outside constituencies. Looking back at David Jones’s situation, for instance, he put far more emphasis on data collection and analysis than on getting to know people. So he didn’t begin to build trust and credibility with key stakeholders. In his early meetings with the senior management committee, had he focused more on understanding the members, what they cared about, and how things worked in the organization, he would have been much less likely to provoke defensive reactions.

Mistaking titles for authority. When you’re identifying the power players in your new company or unit, it’s easy to turn to the usual suspects—large stakeholders, your new boss, some of your peers, and your direct reports. Those aren’t the only true influencers, however: every company has an informal or “shadow” organization as well as a formal one.3 There are always some well-placed, highly respected managers in the organization whose influence far exceeds their formal authority.

Keeping this pair of pitfalls in mind, the best way for onboarding managers to stockpile precious relationship capital is to act deliberately—targeting the right people, assessing those individuals’ agendas and alignments, and forging connections based on common interests. When it comes to identifying key players, it’s probably best to radiate out, carefully working through a comprehensive list of parties in the unit, in the company, in the larger organization, in the partnership community, in the analyst community, and so forth. (See the box “The Stakeholder Checklist” for a rundown of potential targets for your attention.) Your new boss may be able to help you narrow the field, as can a representative from HR.

Once you’ve figured out the “who” side of the equation, you’ll need to focus on the “what.” What agendas are key stakeholders most interested in pursuing? How do their interests line up with your own, and where are they in conflict? Why are these stakeholders pursuing these agendas? When do irreversible business decisions absolutely, positively have to be made—where are the key decision points, milestones, and other action-forcing events?

As a transitioning leader, you enter the organization with a zero balance in your relationship account. As discussed in chapter 3 on corporate diplomacy, you can build up that account quickly by understanding where others are coming from—and, when possible, helping them advance those agenda items that are good for both the organization and the individual.

Aligning Expectations

David Jones was positive he understood the mandate from Energix’s CEO—bring structure to a firm that had long conducted business on the fly. More process, less improvisation. But the COO’s interpretation of the organizational-change challenge didn’t quite match the goals and expectations of others on the senior team. Which, of course, points out the importance of the third imperative for onboarding executives: ensure that you understand what the expectations for success are and that you can accept those goals. Otherwise, you, like David, can fall into the following transition traps.

Failing to check, and recheck. The expectations that David and his new boss negotiated during the recruitment process weren’t necessarily the ones others in the company agreed to. How is that possible? Because recruiting is like romance, and employment is like marriage: during the recruiting period, neither party gets a complete view of the other. Both the leader and the organization put on their best possible faces, not necessarily to deceive but to accentuate the positive. So the organization may come away with inflated expectations of what the new hire can accomplish, and the new hire may think he or she has more authority to make changes than really exists. As a result, someone like David comes in, confident in his mandate, acts on his beliefs—and generates a predictable backlash.

Missing unspoken expectations. Some people simply are better communicators than others; this applies to bosses as much as it does to spouses, customers, business partners, or any other counterpart. The CEO of Energix wasn’t articulate enough, it seems. He left out some important elements that impacted David’s mandate—for example, that the real first priority was to successfully launch the next-generation turbine. It’s therefore essential for the onboarding leader to tease out all of the new boss’s aspirations and goals for the unit or company. Triangulation can be a useful technique for doing this: ask your boss the same question in three somewhat different ways, and see whether the answers vary. Testing comprehension can be another good tactic: during important conversations about expectations, summarize and share your understanding of critical takeaways from the discussion. You can do this verbally, as the session draws to a close, or in writing, in a follow-up e-mail.

Lack of agreement on the business challenge at hand. If you think parts of the organization need a significant overhaul but your boss thinks incremental improvements are in order—or vice versa—you’re in trouble. When views about the most important challenges facing the unit or company are dramatically different, it’s important for you to step back and take the time to educate all key constituencies about the situation; don’t commit to any specific goals until all parties can get closer to agreement.

Negotiating expectations and resources separately. Onboarding leaders often get into trouble by negotiating expectations and resources sequentially and not simultaneously. Usually this happens when the transitioning executive is pressed to make commitments before he or she really understands what it will take to meet them. If you’re in such a situation, it’s important to try to judiciously defer decisions until you’re further along the learning curve. It’s not always possible to do this. You can, however, try to negotiate the process of engagement early on—making it clear that you’d like time to diagnose the situation, present an assessment and plan, and then revisit expectations and time lines.

To avert these traps, transitioning leaders need to have five important conversations with their new bosses concerning leadership style, the business situation, expectations for success, resource allocation, and course correction—with the talks happening roughly in that order. (See “The Five Conversations.”)

Creating Onboarding Systems

The onus is on the transitioning executive to become cognizant of her new company’s or unit’s culture, develop the right political connections, and negotiate the correct mandates. But there is much that companies can do to help accelerate these processes for the onboarding leader.

Accelerate cultural adaptation. HR and talent-management experts can provide a range of resources and programs for newly hired executives. Some are very easy to create and implement, such as providing an updated list of important terms and acronyms used in the company. Others are more difficult to deploy but can pack a powerful punch, such as giving newly hired leaders early insight into the organization’s norms and values.

To do the latter, the company’s hiring managers and the senior team have to be open about the culture, and willing and able to describe it and discuss it in great detail. Of course, some organizations don’t like opening up about their cultures for fear that they’ll scare away talented recruits who don’t consider themselves a match. Better to be up front, however, lest new hires claim a bait-and-switch: they think they’ll be operating in a certain culture and in fact are dealing with a completely different one.

Given a willingness to be open, the company can use a variety of means to capture and describe the culture for new leaders. For instance, I worked with one leading diversified health care company to research and write a compact account of the history and culture. This proved to be an invaluable resource to transitioning executives. In other situations I have created compilations of short video interviews with successful “onboarding survivors.” These leaders, who’ve been there and done that, can obviously impart critical insights to newly hired executives. Companies can also assign a “cultural interpreter” to the onboarding manager; that way, she’ll have a go-to resource for questions and insights about the corporate culture.

Accelerate the development of political connections. In effective onboarding processes, companies identify the full set of critical stakeholders and engage them before the executive formally joins the organization. Typically, a point person from HR touches base with the new hire’s boss, peers, and direct reports to create this list. This point person also may encourage and support the transitioning executive in setting up and conducting early meetings with these stakeholders. New leader assimilation sessions and other structured assessment tools and programs can play an important role in speeding up relationship formation as well.

If the dedicated resources aren’t available to support the process just described—for example, in a smaller company with less staff to assign to onboarding people—HR can instead provide hiring managers with a template to create a top 10 list of people with whom the transitioning leader should connect early on, as well as a template for drafting introductory e-mails to those people. Companies can also give transitioning executives tools, such as the influence mapping methodology discussed in chapter 3, to help them diagnose informal organizational networks, identify key alliances, and draft a plan for gaining support and creating momentum.

Accelerate expectations alignment. The company should make explicit the importance of structured discussions about expectations. These conversations should be a standard piece of the onboarding program, and there needs to be a clear process by which hiring managers and new leaders can negotiate expectations and resources. Some companies rely on the same systems they use for business planning. While helpful, these systems often need to be augmented with significant additional dialogue to ensure that alignment happens up, down, and sideways.

Aside from helping transitioning executives succeed in the three critical areas of culture, alliances, and expected outcomes, companies must also provide transition support in real time. Too much information early on can overwhelm, but waiting too long to impart critical data can create post-transition regret: “Why are you telling me this now, when I’ve already made mistakes?” In those first few days and months, onboarding executives will need a rolling supply of information from reliable resources who are willing to remain on standby for questions.

And finally, there must be a coherent relationship between the recruiting process and the onboarding process. Put another way, the best transition support systems can’t compensate for the sins of poor recruiting—and there are far too many organizations out there that focus on bringing “stars” rather than “role players” into the fold, failing to consider whether those people are actually the best fit for the organization. An executive might have the “right” knowledge and experience but not the leadership style or values to match the company’s culture. This certainly appears to have been at the root of David Jones’s problems at Energix.

Companies that want to integrate their recruiting and onboarding processes must move beyond the standard linear process of job specification, interviewing, and hiring (see figure 4-2). They’ll need to assess the risks and trade-offs of hiring internally versus externally given the business situation. If the company requires a complete turnaround, for example, it’s less risky to hire from the outside than it would be in the case of a realignment. Why? Because people in the organization are more likely to be open to, and perhaps even close to desperate for, outside perspectives.

FIGURE 4-2

Integrating recruiting and onboarding

Hiring managers also need to think through their tolerance for risk and the associated trade-offs between capability and fit. As the interviewing process proceeds, they can develop a Transition Risk Profile for the onboarding executive that identifies specific areas of support needed to reduce the risk of generating fatal reactions from the organizational immune system. Finally, note that the onboarding process can generate insight into company culture; this should be fed back to the system to inform recruiting in the future.

Onboarding Checklist

- How can you accelerate your learning about the history and culture of your new organization? Are there cultural interpreters who can help you understand the nuances?

- What do you need to do to strike the right balance between adapting to the culture versus trying to alter it? How can you avoid triggering a dangerous immune system attack?

- Who are the stakeholders—within your new organization and externally—who will have significant influence over whether you can move your agenda forward? What do they care about and why?

- What can you do to speed up your ability to build the right political “wiring” in the organization? Are there resources available to help you do this?

- How can you assure that expectations are in alignment with your boss? Your peers? Your direct reports? Other importance constituencies? Could the five-conversations framework help you do this?

- Are there other processes or resources in your new organization that could help speed up the onboarding process?