CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 8

The STARS Portfolio Challenge

Andy Donovan was hired into Zetacam, a consumer electronics company, as vice president of customer service. He was responsible for the company’s three major regional service centers, which had just recently been consolidated; they had previously operated as independent units. An experienced operations manager, Andy understood that he was expected to improve performance in all three centers while harmonizing their structures, systems, and cultures.

In his first two weeks on the job, Andy traveled to each of the centers to meet with the regional directors and their staffs, as well as the front-line supervisors and their employees. He wanted a firsthand look at how the centers were organized, how they used resources and technology, and what their climates and work cultures were like. This information, he figured, would help him define his priorities and develop an improvement plan to present to his new boss, Zetacam CEO Christine Rau.

In his travels, Andy encountered three quite different business situations. The first center he visited gave him cause for both encouragement and concern. The good news was that it consistently provided timely, high-quality service to customers. Furthermore, his interviews with front-line supervisors and employees revealed that the center boasted strong processes and systems and, most important, a well-trained and serious-minded workforce proud of its problem-resolution capabilities and its reputation for high performance. Andy was troubled, however, by a subtle but unmistakable attitude of complacency among some center employees. When he questioned them about plans for improvement, for example, he got the sense that they didn’t think there was much need or opportunity to drive things forward.

The second center was managed by the longest-serving of the three regional directors. It was also the largest of the three centers, serving customers in some of the most heavily populated areas of the United States. Andy’s review revealed a history of good performance but signs of slippage in the past twelve months—the chief one being an uptick in the number of customer complaints. But when the VP interviewed the director and his team, and the supervisors and their subordinates, he was struck by their lack of concern about this issue. The site’s customer satisfaction scores had dipped only slightly—and that was mostly because of product quality issues and resource constraints, the managers and employees told Andy. The customers were becoming “too demanding,” they said. For his part, the regional director seemed happy to downplay the problems. He also seemed a bit burned out, Andy noted. The VP concluded that, without even recognizing it, this customer service center was, little by little, losing its effectiveness.

The third center had very serious problems—performance woes that had, in part, driven Zetacam’s decision to consolidate the management of its customer service centers and hire Andy. Customers’ complaints had been piling up and were becoming increasingly strident—grievances that could be heard all the way up the organization’s chain of command. In his discussions with center managers, supervisors, and employees, Andy discovered a seriously demoralized workforce. Employee turnover was unacceptably high and many of the supervisory losses were people who had been identified as having high potential. The regional director, Barry Shields, had been brought in just eight months prior, ostensibly to right the ship. He had immediately spent heavily on new information technologies that he believed were critical for boosting performance. Facing budget pressures, Barry had cut everything else down to the bone. So far, however, there was little to show for all those investments in IT. There were certainly glimmers of progress at this center, Andy thought, but he left the building convinced that this group would require lots of his attention.

Back at headquarters, Andy contemplated his strategy for improving customer service operations. He wanted to preserve the positive attributes of each center but also integrate critical structures and systems as well as eliminate the root causes of negative performance. Even during this period of transition, the centers had to maintain acceptable levels of customer support; he couldn’t afford a severe drop in satisfaction scores.

Andy had no direct reports beyond the three regional center directors. He had planned to reach out to his peers in corporate HR and finance for advice and possible resources. But each of the customer service centers also had staffers in critical functions— such as operations, quality control, and training—from whom he could potentially draw ideas. After digesting his observations and jotting some notes about how to proceed, Andy sat down with his new boss. He started to share his impressions, but Christine cut to the chase: “Are you planning to replace Barry?”

The STARS Portfolio Challenge

In the previous two chapters, I outlined how new leaders should transition into specific business situations as defined by the STARS model—turnarounds in chapter 6 and realignments in chapter 7. The reality, however, is that you’ll rarely encounter a “pure” situation. It’s much more likely that you, like Andy Donovan, will inherit a complex mix—a STARS portfolio, with different parts of your organization immersed in their own unique business situations.

The good news is that the tools developed in the two preceding chapters can still be applied in such complex environments. You can use the systems-analysis approach outlined in chapter 6 to conduct a thorough diagnosis of the discrete business situations you’re facing in various parts of the organization. And you can use many of the proactive change tools discussed in chapter 7 to develop your approach to creating and building the momentum within different business segments. The crucial difference, however, is that you’ll be dealing with multiple STARS situations in parallel. This has major implications for how you should organize to create momentum, how you should build your team, and how you should adapt your leadership style to diverse pieces of the business.

First off, however, you need to get a good read on all the possible STARS situations being reflected in your organization— which means conducting a STARS portfolio analysis, as illustrated in figure 8-1. You can slice and dice the organization in a variety of ways—looking at units, products, projects, customers, processes, or facilities. The “right” unit of analysis will depend on the nature of your responsibilities. For instance, it definitely makes most sense for Andy to consider the customer service centers as his primary point of analysis.

FIGURE 8-1

The STARS portfolio analysis grid

At different times during your leadership tenure, different parts of your organization will almost certainly be thrust into transitional situations unique to that particular unit or function. The following grid can help you map out the various STARS situations reflected in your organization and determine your priorities for creating change.

The next step is to denote which pieces of the business belong in which STARS category—start-up, turnaround, accelerated growth, realignment, sustaining success—using the table in the figure. For instance, Andy can clearly categorize the first Zetacam service center as being in a sustaining-success scenario; the second as being in a realignment situation; and the third center as being in a turnaround state. Note that you don’t necessarily have to fill up the entire table; it’s entirely possible that all the pieces of your business will fall under just one or two categories.

Now do some quick-and-dirty prioritization. Using the right column, take 100 “priority points” and divide them among the units of analysis represented in your STARS portfolio, according to the time and attention you think you’ll need to give each during the next six months. It’s plausible, for instance, that Andy would decide to allocate 50 percent of his time to the turnaround of service center three; 35 percent of his hours to the realignment of service center two; and 15 percent to ensuring that service center one continues to sustain its success.

Finally, put an asterisk in the grid next to the type of STARS situation you most prefer managing. Some executives may relish the fast-track challenges of turning around a foundering organization; others might thrive on managing the incremental but impactful changes that can be necessary in realignments or sustaining-success situations. Marking your personal preference can help you recognize whether your priority ratings reflect the true needs of the organization or simply your own biases—the business problems you particularly enjoy tackling and the ways you like to work. If you put the asterisk next to the STARS category to which you also assigned the largest number of points, you are either tremendously fortunate that the business challenges you’re facing match up so well with your preferred areas of focus, or your personal preferences have skewed your priorities.

Driving Execution

Once you’ve charted the mix of STARS situations reflected in your organization, you can use the information to determine the approach you should use to create momentum for change—which leads us to a discussion about the science of driving execution.

Physicists and researchers for centuries have been studying thermodynamics—the process by which engines turn fuel into motion. Similarly, transitioning leaders who are dealing with a complex mix of STARS situations must quickly become experts in something I call organizational thermodynamics—the means by which a business’s products and processes (execution engines) convert its human and financial capital and management support (organizational fuel) into the right early wins (forward motion). As illustrated in figure 8-2, the execution engines comprise dedicated project teams, led by people who can get things done and supported by robust systems and processes.

FIGURE 8-2

Organizational thermodynamics: An overview

Execution engines transform “fuel” in the form of talent, funding, and support into work—the early-win initiatives that will help to create momentum.

Identifying Your Centers of Gravity

To design powerful execution engines for your organization, you must begin “with the end in mind,” as the author Stephen Covey so aptly put it in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People.1 In this case, the desired goal is to secure some early wins that will help you build the momentum for change in the business. You’ll need to identify three or four areas in which you have a good chance of realizing rapid improvements—think of them as your “centers of gravity.” The best candidates are business problems that you can get to relatively quickly, that won’t require too much money or other resources to fix, and whose solution will yield very visible operational or financial gains. Obvious targets might be those parts of the business you had categorized as being in turnaround mode in your STARS portfolio analysis grid. Andy, for instance, should think hard about how to achieve some quick improvements in customer service center three; first, though, he decided to assemble a SWAT team of high performers from the other two centers and task them with identifying priority improvements. This can’t be the only center of gravity he focuses on, obviously, but it’s an important start because of the extent of the problem and the magnitude of senior management concern.

In your assessments, it’s important to keep the STARS states top of mind: how you go about getting early wins will obviously depend on the context. For example, because customer service center three is in a turnaround situation, Andy needs to quickly stop the bleeding. That would constitute a good early win. But in customer service center two, which is mired in a realignment situation, Andy will have to find ways to make people aware of problems they can’t see at this point. The new VP will also have to confront complacent staffers in customer service center one, which is trying to sustain its success, as well as identify effective ways to transfer best practices from that center to the others.

Besides acknowledging the context, you’ll want to maintain your focus: if you take on more than three or four significant initiatives, spread across the different parts of the organization, you risk diluting your efforts. Think about it in risk-management terms: pursue a small set of initiatives so that big gains in one area will balance any disappointments in another.

As you’re identifying how and where to achieve early wins, consider two additional factors: first, don’t get caught in the low-hanging fruit trap—focusing all your energies on achieving small tactical victories that don’t contribute to the overall campaign. Yes, early wins should help you create change in the short term; but they should also help you lay the foundation for achieving longer-term goals. Second, it always pays to find out what your boss considers “early wins.” For Andy Donovan, this means thinking hard about how to respond to Christine Rau’s blunt question about firing the regional director of service center three. Her query is a sure sign of her concerns for that unit and a sure sign to Andy that his attention is needed there. Still, if Andy fires Barry without taking time to consider whether the director’s ideas and plans are likely to bear fruit, or whether Barry has the right competencies but simply needs more support, he may send the wrong signals to others in center three. (For help identifying and assessing your potential centers of gravity, see figure 8-3.)

Early-wins evaluator

For each possible center of gravity, carefully answer the following questions, then total the scores. The results should serve as a rough indicator of the potential for creating quick and impactful improvements in that particular area of the business.

The result will be a number between 0 and 16. You can use this rough measure to compare the attractiveness of several candidate focal points. Obviously, the higher the number, the better. Initiatives that score higher than 12 are very good bets; those that score under 8 are marginal. Take care to use common sense in interpreting these numbers: If the candidate opportunity scores 0 on the first question, for example, it really doesn’t matter if it scores 4s on all the others.

After a period of analysis, Andy ended up identifying four initiatives he would use to secure early wins: in addition to turning things around in customer service center three, Andy wanted to standardize performance measurement and evaluation across all three centers, share best practices from center one with the other two units, and assess the costs and benefits of centralizing several important center functions. Then he turned his attention to securing the necessary resources from corporate and organizing his team (and himself) for action.

Fueling Up

Once you’ve identified your targets for early wins, you’ll need to muster the resources necessary to achieve them—the people, funding, and time required to execute your selected initiatives. These resources constitute the fuel that will power your engines of execution.

In part, you’ll fuel up, so to speak, by making important decisions about who’s on your team and what the strategic direction should be (defining the mission, the objectives, the core competencies of the organization, and other critical elements of the strategy). But you’ll also need to take a hard look at existing patterns of activity in the organization you’re joining: How are people spending their time, and what does that say about their priorities, work habits, and individual strategies? This was, in part, what Andy was looking at in his early assessments of the three centers. The resulting insights served him well when the time came to focus energy on his early-win initiatives.

A good way to uncover these patterns is to ask the members of the team you inherited to list the top ten things they spend time doing in a typical week and the rough percentage of effort allocated to each. You’ll naturally have to be cautious when interpreting the results; people won’t be completely transparent in their recordings of how and where they devote their energy. But the data may reveal which activities are receiving disproportionate amounts of attention and which activities could use more. Their responses may also provide useful fodder for a “stop-alter-continue-start” analysis (see figure 8-4). In other words, to secure the early wins you’ve targeted, what will you stop doing to free up resources? What will you alter to better align employees’ efforts with your objectives? Which tasks and processes should remain status quo? And what new patterns will you try to initiate?

FIGURE 8-4

Stop-alter-continue-start assessment

While assessing your resources, identify which current activities you will stop, which you will alter in significant ways, which you will continue pretty much as they are, and which you will start altogether.

Andy Donovan’s review of the activity patterns in Zetacam’s three customer service centers revealed which projects and processes were consuming more value than they were creating. His assessment also suggested that there was still significant duplication of efforts across the three centers, which justified the original plan to consolidate and pointed out areas of particular focus for Zetacam’s new customer service VP. Using all this information, Andy was able to plan his projects and initiatives, and the necessary resources, for pursuing early wins.

Building Your Execution Engines

Once you have garnered the resources necessary to make change happen, it’s time to construct the execution engines that will actually ensure that the work gets done. This critical stage requires much consideration; after all, how you achieve the early wins is as important as the victories themselves. Indeed, the approach you use to drive execution can be a powerful tool for ridding the organization of its worst dysfunctions. So your execution engines should be able to perform double duty: facilitate quick and early organizational improvements, and establish new standards of behavior.

Every early win sought should be viewed as a project to be managed; the makeup of the execution engine will naturally flow from your definitions of project charters, your assignment of the project teams responsible for those charters, and the disciplined project management methods your people employ. You’ll obviously need to pick the right people to lead these projects—and not necessarily just the reflexive supporters of what you’re trying to do. Sometimes putting a thoughtful skeptic in charge of an early-win project can be a powerful way to win over an important ally.

Beyond thinking hard about project leadership, you should also be disciplined about outlining the project focus—carefully defining the scope and goals—and thinking through the politics involved with project oversight and participation. It may be important, for instance, to have influential representatives from critical constituencies involved from the start so they can help build support for changes implemented as a result of the project.

Finally, you’ll also need to take inventory of the skills and time commitments necessary to get projects done—and then follow up by providing resources and support. Do the project teams have the right kinds of expertise? Do the team members need additional training—more information about structured problem solving, for instance, or team-building methodologies? This inventory process provides yet another opportunity for establishing and reinforcing new norms of behavior.

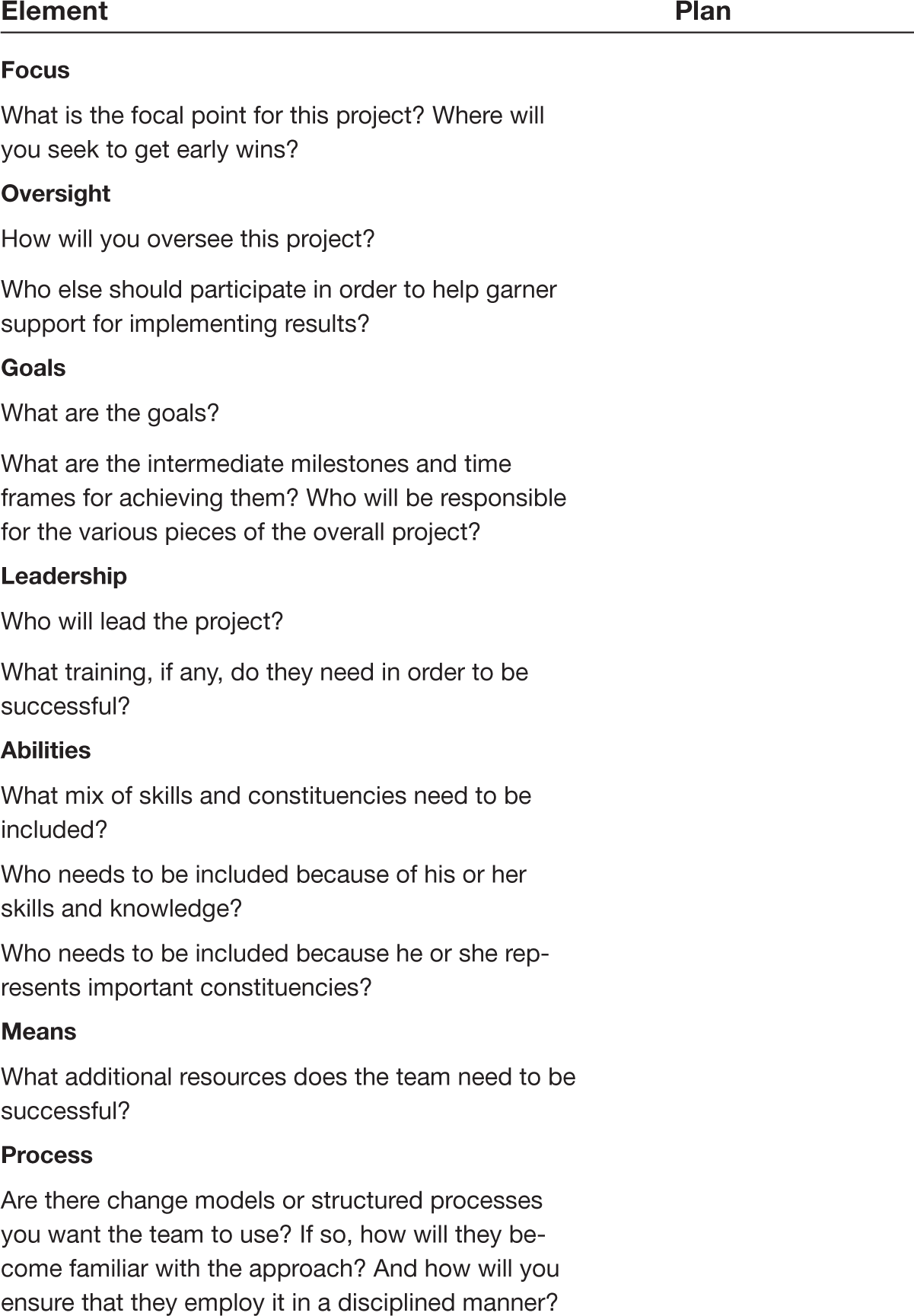

When building your execution engines, consider using the FOGLAMP project-planning template shown in figure 8-5. FOGLAMP is an acronym for focus, oversight, goals, leadership, abilities, means, and process. As the name implies, this tool can help you cut through the haze of organizational minutiae and illuminate the essentials.

STARS and the Personal Adaptive Challenge

Leaders who are dealing with a collection of STARS situations must be cognizant of not just how they manage discrete parts of their organizations but also how they manage themselves. As I have stressed throughout the book, transitioning executives should seek to understand both the organizational-change challenges and the personal adaptive challenges associated with their new roles. When you’re facing a complex mix of STARS situations, there are typically two main personal adaptive challenges: adjusting your leadership style to deal appropriately with the various pieces of the business, and building a team that complements you so you can capitalize on your strengths, compensate for your weaknesses, and channel your energies in the areas best suited to your skills and interests.

In those first few hours, days, and months in a new leadership role, you’ll naturally want to look forward—toward the challenges you face, the strategies you’d like to employ, the personal and professional goals you’d like to meet. Instead, it might be more helpful to look back at your history in various STARS situations. Take a few minutes to record your experiences leading start-ups, turnarounds, accelerated growth scenarios, realignments, and sustaining-success situations (see figure 8-6).

FIGURE 8-6

Tracking your STARS trajectory

Use the grid below to chart your experiences with particular STARS situations. In the first column, identify the significant management jobs you’ve had in your career. Categorize each job based on the type of STARS situation you confronted and the experiences you gained there. Put check marks in the appropriate cells, then tally up the number of check marks in each column. This should give you a rough sense of your STARS experience to date.

Are your experiences mostly concentrated in one or two STARS situations, or more broadly? How do your experiences align with the assessment of your STARS portfolio at the beginning of the chapter? That is, does the situation play to your strengths or does it focus on STARS categories with which you have less experience? Recall, too, the discussion in chapter 7 about heroes and stewards. When you’re leading a complex mix of STARS situations, the issue is not whether you should focus on being one or the other; the issue is figuring out which style will be most effective in different parts of the business, and who is going to provide the right mix of heroism and stewardship.

If Andy has a heroic style of leadership, for instance, it would be natural and perhaps appropriate for him to want to focus on the turnaround in customer service center three. Likewise, it would be appropriate for him to appoint a hero to lead the project team charged with coming up with a turnaround strategy for that center. But a bigger challenge for him will be deciding who will provide the necessary stewardship in centers two and one, which are facing realignment and sustaining-success situations, respectively. Will Andy personally be able to adjust? And, based on his ability to alter his leadership style (or not), whom should he pick to lead the early-win projects at those sites?

Based on your self-assessment, you may also need to think about whether or how to develop yourself as a STARS generalist. There will always be a market for management specialists, of course—especially for turnaround artists. But the reality is that most management positions, and virtually all business careers, require leaders who can deal with the full spectrum of STARS situations.

Looking outward, toward your direct reports, your assessment of the team you’ve inherited should also reflect your understanding of the collection of STARS situations you inherited. Do you have the right talent on hand to accomplish your goals? Based on team members’ experiences in certain STARS situations, whom should you assign to which roles? It’s not uncommon to inherit a team that could easily handle a realignment situation—but would get eaten alive during a turnaround. Indeed, if you need to recruit or promote new talent, it’s very much worth keeping the STARS portfolio concepts in mind to make better-informed hiring decisions. Before you start interviewing, take a step back and ask: which part of the STARS portfolio am I hiring this person to manage? If the skills match, the offer should be a relatively easy one to make.

STARS Portfolio Checklist

- What is the mix of STARS situations that you have inherited? What are your priorities across the portfolio?

- What are your STARS preferences, and how much experience do you have in the various categories? Is there a risk that you will focus too much attention on the STARS categories that you most prefer?

- Given the portfolio you have inherited, what are the implications for where and how you will seek early wins in the various parts of the business?

- What are the most promising centers of gravity? Are there ways you can drive improvement across the entire business? Leverage resources in one area to get wins in another?

- Given your early-win objectives, how will you marshal the resources to go after them? What do you need to stop doing?

- How will you build and manage the execution engines you need to get your early wins?