CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 2

The Leading-Former-Peers Challenge

Julia Martinez’s promotion to director of marketing at Alpha Collaboration took her former peers, many of whom would now be her direct reports, by surprise. Julia’s boss and mentor, Thomas Collins, was good at many things, but communicating about people issues was not one of them. Within a week of being promoted to vice president of sales and marketing at the midsize team collaboration software company, he appointed Julia, one of the five marketing managers who had reported to him, to be his successor.

Julia inherited an organization that had made impressive strides in the past few years, a primary reason for her boss’s promotion. Effective marketing had helped propel Alpha to a leading position in providing team collaboration support for small businesses. At the same time, the company was facing increasing competition from several well-funded start-ups. These emerging rivals, in an effort to build market share, had priced their services to undercut Alpha. Forced to respond with price reductions of its own, Alpha had begun to experience pressure on its operating margins. Customer retention also was becoming an issue because of the intensifying competition, even as new acquisitions were showing signs of slowing.

Julia had been convinced for some time that Alpha needed to change its marketing strategy. Rather than engage in the “broadcast” approach that Collins had adopted, she thought Alpha needed to sharpen its focus: identify the most attractive market segments and create targeted campaigns to reach customers in those groups. She also thought that the organization should shift its resources from customer acquisition to customer retention and brand building. Finally, she was concerned that too many projects were under way to develop potential new service offerings, and that they were insufficiently grounded in solid market research.

Collins was preoccupied with his own transition (the previous VP of marketing had left unexpectedly to join another company), and Julia hadn’t had time to discuss goals and expectations with him. But she was confident she could sell him on the new direction. After all, Collins had hired her into Alpha. For the past three years, she had been the company’s manager of marketing communications and had built a highly capable team that developed product-related materials. But Julia also boasted a strong technical background, including a master’s degree in applied statistics and five years as a market research analyst at a leading consumer-products company. So she understood the power of segmentation and was confident she knew how to implement it.

Julia did have some concerns about her new team, however. First, there was Andy, a talented if somewhat ego-driven leader in marketing strategy. He had viewed himself as the logical candidate for advancement. Julia knew that her promotion had been a blow to him, and she wondered if he’d be able to get over his disappointment and work effectively under her direction. If she could bring him on board, Andy could be an important asset and ally in pursuing her new ideas. But the last thing Julia needed was a resentful former peer undermining what she was trying to do.

Another team member, Amanda, posed a different challenge: as a manager of marketing support, Amanda had done a solid job in terms of overseeing projects and driving execution. But she was not a particularly inspiring leader, nor perhaps was she the person Julia needed in that role if she were to implement her new strategy. Over the years, Amanda had often sought Julia’s personal and professional advice; they had become, if not friends, something more than business colleagues. Now Julia would be the one evaluating Amanda’s performance.

In addition, Julia planned to manage her team differently than Collins had. He was very hands-on, a style that suited him. Julia, by contrast, preferred to vest more authority with the members of her team and to encourage shared commitment and collective accountability to the greatest extent possible. With all that in mind, as soon as the schedule allowed, she planned to take her team off-site for a one-day situation assessment and strategy discussion.

Finally, Julia was somewhat apprehensive about trading her old peer group for a new one. Many of the people she’d now be interacting with day to day were significantly older and more experienced than she was. Some had a lot of influence in the organization, and one had been a candidate for the VP position Collins was moving to. Now she was just the new kid on the block, and Collins’s kid at that. Julia wondered how best to engage with her new peer group during her transition.

All these concerns crystallized for Julia the day after her promotion was announced: she went to the cafeteria to get lunch, as she usually did. When she entered the seating area, she saw her new peers eating together at one table and several of her former peers sitting at another. Suddenly the dining tray felt heavy in her arms.

The Leading-Former-Peers Challenge

If it hasn’t already happened, it is very likely that you will experience the challenge of leading former peers at some point in your career. Most business leaders do; many go through it multiple times as they climb the corporate ladder. But too many learn to make this challenging transition through trial and error. They make predictable mistakes, such as not establishing sufficient authority with their new teams or not understanding that their relationship with their boss must change. They learn hard lessons and apply them in future transitions, but this is an inefficient, wasteful process.

One scene in Shakespeare’s Henry IV (act V, scene 5) brilliantly captures the tensions leaders face when they are promoted in their organizations. Henry is the Crown Prince of England, destined to inherit the throne, but he spends much of his youth partying with disreputable characters, in particular the drunken Falstaff and his cronies. His father dies, and Henry is to be crowned king. During the coronation scene, Henry very publicly rejects Falstaff—“I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers.”—and sees first-hand how this slight hurts his old friend. This exchange signifies the major shift Henry makes from dissolute youth to one of the great rulers of England: his role changed dramatically and, as a result, so did many of his long-standing relationships.

A similar shift takes place when executives ascend to higher positions within their organizations: when you’re promoted to lead the people with whom you formerly worked side by side, the nature of your interactions with those individuals will change in important ways. And, in most cases, new leaders are left to figure out how to navigate these psychosocial challenges on their own—as Julia Martinez was.

Chapter 1 of this book outlined the basic organizational challenges leaders face when they’re promoted: How should you delegate and communicate differently? How do you balance breadth and depth in a new role? How do you develop new competencies and project the sort of presence that is appropriate for your new job?

Leaders who are promoted to lead former peers do face these challenges and it would be easy to imagine that tackling them in an environment you’re familiar with would be easy. After all, you’ve got the lay of the land (the culture and critical players, the business and what drives it), and you’ve probably banked some “relationship capital” to boot.

On the contrary, being promoted to lead people who were formerly your peers is among the toughest transitions you can make, precisely because of the complex web of organizational relationships you’ve created over the years and must now redefine—with your boss, former peers, and new peers. You think you know everyone, and everyone thinks they know you. But those relationships were shaped, in part, by the roles you previously played. The protocols, perceptions, and interactions must all be different now.

Relationship Reengineering

The imperative for Julia Martinez—and for all leaders who find themselves moving up and having to lead their former peers—is to engage in what I like to call “relationship reengineering.” Global businesses often try to improve their odds of success by fundamentally reengineering processes to meet their changing needs. Similarly, transitioning executives can improve their chances of realizing positive change by redefining their relationships in light of shifting roles. Doing this means focusing hard on your interactions with critical people, understanding how those relationships need to change, and developing a plan for making the necessary shifts. Specifically, you should try to adhere to the following basic principles:

- Accept that relationships have to change.

- Focus early on rites of passage.

- Reenlist your (good) former peers.

- Establish your authority deftly.

- Focus on what’s good for the business.

- Approach team building with caution.

Accept That Relationships Have to Change

In the process of working together for long periods and facing down shared challenges, work colleagues can become friends, or something close to it. An unfortunate price of promotion, however, is that your personal relationships with former peers must become less so. Close personal relationships and effective supervisory ones are rarely compatible, for several important reasons. First, you can’t afford to have your judgments about important business issues clouded by your personal feelings about the players involved. And second, you can’t allow the perception to take hold among the members of your team that you play favorites.

In the early months of her tenure, Julia could very well find herself sitting across the table from Amanda, needing to deliver hard-edged performance feedback but experiencing a desire to cushion the hurt. If she succumbs to the temptation to go easy, Julia could undermine not only the company’s performance but her own leadership. If she does what’s right for the business, she will irreversibly alter the relationship, and she will see it in Amanda’s eyes. There is a right answer, but that doesn’t make it easy. Julia should take care to send a consistent message to everyone from the start: “I will be fair in my evaluation of you.” Then, of course, she has to live up to this by translating the rhetoric into action on a consistent basis.

Focus Early on Rites of Passage

Those first days of an internal promotion are more about symbolism than substance. Indeed, certain rites of passage can help to establish the new leader and, hence, simplify the relationship reengineering that must be done. In an ideal world, Julia’s boss, Thomas Collins, would have set the stage for her promotion—specifically, meeting privately with Andy to share his reasons for promoting Julia and then calling the team together to announce his successor. This would have laid the groundwork for Julia to transition smoothly into her new role.

It also would have helped if the company had had a solid process for communicating about internal promotions. This means formal and informal messages sent to all employees about the selection process and outcomes. In doing this, it’s important to give attention not just to content but also to timing. In one organization I worked with, all formal promotion announcements were communicated via e-mail in the late morning. This meant that people had time to absorb the implications and perhaps talk about the promotion over lunch. It also gave the newly promoted leader time to reach out to key stakeholders on the same day, participate in a short meeting with available members of the new team, and begin to initiate one-on-one meetings.

It didn’t unfold this way for Julia, however, so she has to write her own “coronation scene,” so to speak. This should include convening her team for a short meeting—essentially, providing a chance for everyone to acknowledge publicly that a shift has occurred. Julia should carefully draft a short script around a few central messages: that she is looking forward to working with the team to move the organization forward, that she values all team members’ contributions, and that she is looking forward to meeting with each of them individually. (Ideally, she would have already begun setting up those meetings.)

Reenlist Your (Good) Former Peers

Behind every “happy” promotion are the one or more ambitious souls who wanted the job but didn’t get it. As much as practical, companies should prepare the people who are not going to get promoted. The ability to do this is rooted, in part, in performance review and succession systems that do a rigorous job of evaluating performance and, critically, that shape realistic expectations about the potential for advancement.

If the promotion process is managed well, the final choice for the position will almost certainly disappoint some—but it should never be a surprise. More often than not, however, newly promoted leaders like Julia have to deal with former peers who may feel dejected, angry, or even victimized. Some will be able to get past their disappointments to support your initiatives for getting things done; you’ll need to find ways to reenlist these former peers.

You’ll of course need to recognize that disappointed competitors will go through stages of grieving similar to those defined by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance) and that it will take some time for them to work through these feelings.1 If your former peers are good and you want to keep them, then you should respect this and do what you can to help the adjustment process along. A good first step is to communicate and reinforce that you recognize what people have contributed to your organization’s success to that point. This is probably best done privately unless there is an authentic moment when you can do so publicly. Otherwise it’s easy to come across as condescending.

You also should think hard about whether and how best to engage with disappointed direct reports more directly about what they are experiencing. Should you talk with them right away or after they’ve had more time to process the change? Should you address their concerns directly or obliquely? Should you be empathetic or matter-of-fact in your communications? It really depends on the person and your relationship with them. If they are disappointed but not resentful, comfortable talking about such things, and you have a good relationship with them, then it can be effective to directly address the issue. If, as was the case with Julia and Andy, they harbor some bad feeling or are uncomfortable openly discussing such things, then it’s probably best to leave the ball in their court, while at the same time signaling that they are valued members of the team.

If and when you do have these discussions, remember that your former peers’ concerns about their careers—and associated fears that they have been dead-ended—will probably rank high on their lists of priorities. It’s easy for them to interpret your promotion as an implicit criticism of their abilities and potential. So if you can genuinely help to alleviate those concerns, then you should. For instance, if Julia can credibly sit down with Andy and convince him that she is committed to helping him develop and advance, she may have a good chance of reenlisting him and building a critical new direct-report relationship.

Keep in mind, though, that sometimes former peers simply can’t get over perceived organizational or personal slights. As able as they may be, they may not be able to work for you. You’ll need to keep a careful eye out to see if people are genuinely getting on board. If after a reasonable period of time they are not, then you’ll need to help these individuals find other opportunities.

Establish Your Authority Deftly

To exert your authority over former peers, you have to walk the knife’s edge between over- and underasserting yourself. You may be tempted to act as a sort of “superpeer”—overplaying your desire to continue coaching, encouraging, and supporting former peers despite the title change. Conversely, be careful not to develop a Napoleon complex in your new role, issuing edicts at will without realizing it.

It’s critical to find the middle ground early on. For instance, Julia might consider putting on hold, at least for a little while, her plans for creating more of an empowerment culture. In those first few months, she should adopt a “consult-and-decide” approach when dealing with critical issues—in part to establish her own authority, and in part because that’s what people at Alpha are used to. By listening carefully (the consult side of the equation), she’ll demonstrate to her new team that she values thoughtful input. By considering carefully and coming to resolution quickly (the decide piece of the equation), she’ll convey both that she is capable of smart decisions and ultimately accountable for results. Once Julia has established a new rhythm with the team, she can engage them in more consensus building if and when it’s appropriate.

Focus on What’s Good for the Business

From the moment your appointment is announced, some former peers, now direct reports, will be straining to discern whether you will play favorites or seek to advance your political agenda at their expense. One antidote to this potentially disruptive dynamic is adopting a relentless, principled focus on doing what is right for the business. Every decision you make should be framed in those terms—so long as you’re genuinely committed to this ethic and prepared to live with the consequences. The sooner your new direct reports see that you’ll be “hard on issues and soft on people,” the better.

A related way to immunize yourself against perceptions that you are playing politics in leading former peers is to adopt what INSEAD professors W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne have termed a “fair process” for making important decisions.2 This means establishing and upholding work processes that are perceived as just—for example, by melding consult-and-decide decision making with “put the interests of the business first” criteria for evaluating alternative courses of action.

A few months into her new role, Julia was able to apply these principles to help rationalize the many projects that were underway at Alpha to develop new service offerings. Although many other parts of the organization were involved in new product development, the marketing strategy component was Andy’s responsibility. Julia knew that any effort to shift the strategy would be a political minefield, not just because of Andy, but because it touched so many sets of interests and agendas in the company. So rather that attack the issue head on, she decided to set up a project evaluation team and put Andy in charge of it (he responded well to the opportunity for visibility). She was able to leverage the relationships she had built outside her organization to staff the team with capable people from sales, operations, and finance.

Critically, she specified in detail the multistage process the team would use to conduct the evaluation. The first stage was a thorough review of existing market research that resulted in the commissioning of a new study to clarify what customers were really looking for. In the next stage, she directed the team to craft qualitative and quantitative criteria for evaluating the costs and benefits of each project. Only then did she have the team assess the existing project portfolio. By this point, no one was disputing the need for significant rationalization, and agreement on what to continue and what to stop was reasonably easy to reach.

Approach Team Building with Caution

The lure of the off-site meeting is strong for many newly promoted leaders. Like Julia Martinez, they have agendas they want to pursue and teams they want to mobilize. “Just let me get everyone together in a quiet place, give me their undivided attention, and we can move mountains,” goes the logic.

No question, an off-site can be a powerful vehicle for mobilizing change. Done right, the meeting can focus people’s attention, break down barriers, build commitment, and leave teams energized, aligned, and ready to do great things. But poorly planned and facilitated, such a meeting can go very badly. In a worst-case scenario, conflicts are exacerbated, opposing coalitions are empowered, and the new leader’s authority is undermined from the get-go. (See the box “Off-Site Planning Checklist.”)

Before you reflexively schedule an off-site meeting, you need to step back and answer two interrelated questions: What am I trying to accomplish? And is an off-site the best way to achieve my goals? There are a number of reasons why you’d answer no to the second query—a chief one being the risk that you’ll fuel the rise of opposing coalitions. If some people are likely to resist the changes you want to make, then an early off-site may only serve to galvanize that group of dissenters, no matter how latent their objections, to the changes the organization is making. Better to start at the micro level—building support one by one and in smaller group meetings before convening an off-site.

Julia Martinez is considering convening an early off-site, ostensibly as a way to launch her attempts to shift the marketing organization’s strategic direction (toward more customer segmentation) and culture (toward shared accountability). This would be a huge mistake, however. She has not laid the groundwork with her boss for creating a new strategy, nor has she established sufficient authority in her new role to introduce democracy.

If Julia decides to go ahead with an off-site, the primary objectives should be diagnosis and relationship building, rather than strategic planning. She and the members of her team can rigorously vet and analyze changes in the business environment and come to a shared understanding of the situation. The data and insights from this meeting could even give Julia the ammunition necessary to convince her boss that a strategy shift is in order. Meanwhile, the collaboration and discussion in this meeting may go a long way toward helping Julia reengineer her relationships with her former peers—showcasing her as a new leader who is firmly but judiciously in control. Once these foundations are in place, she can turn her attention to strategy and process, perhaps by holding a subsequent off-site.

Each of these principles presents its own set of unique challenges, no doubt. But your ability to successfully adopt them can help position you for success in leading former peers. You must also recognize, of course, that you’ll have to grow into your new role—and that it’s going to take some time.

Companies can also do a lot to accelerate the team adjustment process for those who are promoted to lead former peers. One powerful tool is the new leader assimilation process.3 A facilitator, perhaps from HR or an external consultant for more senior managers, meets individually with the new leader and the direct reports and then brokers a joint meeting. The focus of discussions is on expectations, and how the newly promoted leader plans to manage the group. (See the box “The New Leader Assimilation Process.”) Done well, the process can dramatically accelerate the development of working relationships and eliminate key uncertainties that slow team development. It also provides an important rite of passage—it explicitly acknowledges that a significant shift has taken place.

Working with Your New Peers and Boss

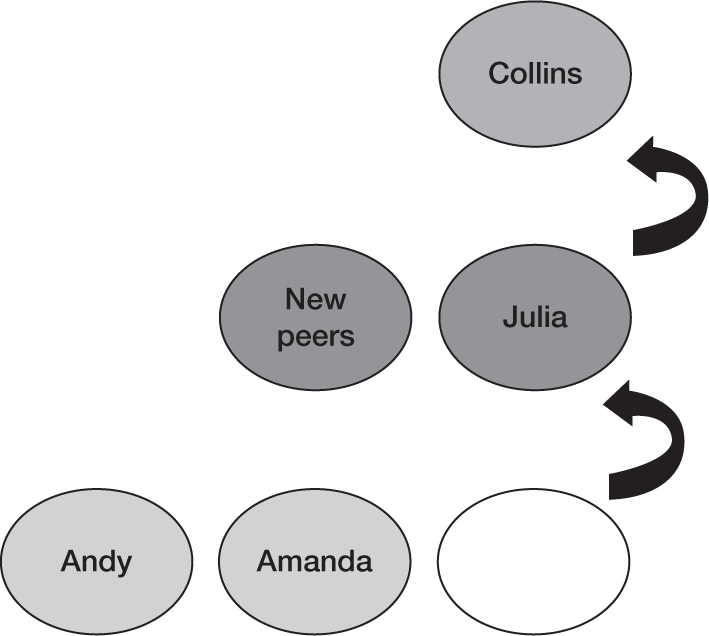

Your relationships with your former peers are not the only ones that need to be reengineered. Like Julia Martinez, you are part of a much larger network that includes new peers and your boss. (See Julia’s network in figure 2-1.)

FIGURE 2-1

Julia’s new network

Working with New Peers

As someone newly promoted from within, you will need to reach out to your new peer group—and interact with them as a peer would—as soon as possible. These interactions must obviously be handled with care and tact: consider that among Julia’s new peers (Collins’s former peers and now his direct reports), there are likely to be disappointed candidates for the VP of marketing job that Collins eventually got. Remember, too, that Julia may be viewed as Collins’s “favored child” because he hired and developed her. So some of her new peers may even try to undermine Julia’s attempts to lead change in the marketing organization simply out of frustration or to subtly call Collins’s selection into question.

With such politics in mind, it’s important for transitioning leaders to strike the right balance between self-assurance and cockiness in building relationships with new peers. You should set up a series of one-on-one meetings with new colleagues and strategize with your boss about how you’ll be introduced at the first staff meeting.

In the one-on-one meetings, you should be asking lots of questions so as to understand the web of explicit and implicit alliances in your new peer group: How can you help your new peers achieve their important goals, and how can they help you? In staff meetings, the right approach early on is usually to listen and respond thoughtfully. As you gain a better understanding of the alliances and culture, and, importantly, build some relationship capital, you can begin to participate more actively. For instance, in Julia’s case, she is younger and less experienced than her peers. She needs to build some credibility with them in her new role. So while it would be a mistake for her to try too hard to prove herself early on, so, too, would it be wrong of her not to “come to the table” after she’s gotten up to speed a bit.

Speaking of coming to the table, let’s reconsider Julia’s cafeteria conundrum: Should she sit with her old peers, her new peers, or turn tail and head back to her office? Withdrawing from the situation is definitely the wrong answer (although that’s what happened in the real situation); Julia would miss a valuable opportunity to set her transition in motion. The “right” answer depends in part on the culture of the organization. It could make sense, however, for her to at least stop by the table with her new peers, say hello, and mention that she will be reaching out to meet with them individually, and that she’s looking forward to working more closely with them. Given the informal social setting of the cafeteria, it probably doesn’t make sense for Julia to insert herself into that gathering—and it might send the wrong signals to her former peers. She could comfortably sit with the members of her old peer group, however.

Working with Your Boss

The trap here is assuming that just because you and your boss are the same people, the relationship will stay the same. Just as your relationships with your former peers will change when you’re promoted internally, so will your interactions with your boss. Shifting roles mean shifting expectations—and different “best” ways of working with one another. Simply put, as you make the transition to a new role, you’ll need to cast off long-held assumptions and adapt your relationship with your boss to meet the needs of both your changed roles.

In Julia’s case, she’s making some potentially dangerous assumptions about how receptive Collins might be to her plan to alter Alpha’s marketing strategy. She needs to meet with him as soon as possible to review the situation and his expectations. If she really believes a shift in strategy is necessary, she should gather her data and prepare her arguments—presenting her ideas in a way that doesn’t suggest she’s criticizing what came before.

Julia also needs to be attuned to the realities of Collins’s own transition: he, too, has been promoted to lead former peers. How well Julia integrates herself with his old peer group will unquestionably reflect on him, good or bad. She is in a position to help him achieve some early wins in his new role, so she should give some thought as to how she might support him in this way.

Finally, there will inevitably be disagreements about how to “be” the marketing director—Julia’s new title, Collins’s old one. He would be right to believe that he knows more about how to do that job than she does. The risk, of course, is that he will try to continue to do Julia’s new job. If his transition is going well, Collins probably will be too busy, even if that is his inclination. But if he is struggling in his new role, he may try to retreat to his comfort zone.

In summary, the challenge of leading former peers is always fraught with difficulty. After some initial struggles, Julia was ultimately able to find her footing in her new role. The relationship with Andy was never developed into a fully productive one. After eight months, he left to join a start-up in a marketing director role.

Leading-Former-Peers Checklist

- How is the network of relationships that you need to succeed in your new role different? Who are the key new people with whom you must build relationships? How must relationships change with your former peers, new peers, and boss?

- What are the key rites of passage that signify you have been promoted and how should you prepare for them? What additional things might you or your boss do to signal that a significant shift is taking place?

- What should you do to help speed up the process of adjustment for your former peers now that you will be leading them? How should you approach reenlisting the talented people in your organization?

- How should you approach establishing your authority? How will you achieve the right balance between being in charge and empowering your team?

- What formal team-building work will you do, if any? What is the right timing and focus for early team interactions?

- How will you approach building relationships with your new peers? At what point will you shift from more of an early observational mode to becoming an active member of that team?

- If you have the same boss, how will that relationship need to change given the new roles you both are playing? How will you approach surfacing and discussing the needed shifts?