CHAPTER TWO

CONTEXT—THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCCESS

It is surprising how many training solutions have no chance of success. The reason might surprise you. Although poor e-learning design is rampant, the most pervasive inhibitor to success may be the failure to scrutinize the training and performance context and take it fully into account.

The many factors that determine training and performance success include:

- Who participates in the design of the training

- What resources are available for training design and development

- Who is being trained and for what reason

- The instructional delivery media and instructional paradigms used

- The learning support available during training

- The performance support and guidance available after training

- Rewards and penalties for good and poor performance, respectively

This chapter considers the importance of context. It starts by examining the prerequisites for success, then discusses the role of good design as the means to success.

Unrecognized Context Factors

Failed training programs can often be chalked up to a number of contextual conditions. The barrier can be an environment that inhibits desired performance. It can be poor training solutions developed without the essential participation of key individuals. And it can easily be a combination of both.

Costly failures may not be recognized for some time, of course. All who are responsible for getting training programs up and in operation revel at the achievement and announcement of the programs’ availability. They most probably receive congratulations from those who can easily imagine that the development and deployment of a new training program is a considerable undertaking. News that trainees like the new programs and are giving positive feedback validates the cause for celebration. All is well. . . . Not necessarily.

Learning failures will be recognized eventually. Even though trainees may appreciate the excuse to escape the usual work routine and to enjoy the donuts provided in the learning center and the good humor of the instructors and staff, organizations do typically come to realize that people are not performing as well as is needed, that new employees take a long time to get up to speed, that complaint levels haven’t dropped, or that throughput continues to deteriorate significantly when additional staff is added. Chapter 1 discusses how effectively organizations, wittingly or not, cover up the ineffectiveness of their training programs and how easily they may come to believe training programs can’t be effective solutions.

Change Is Necessary

“If you continue training the same way you’ve always trained, don’t expect to get better results,” says DaimlerChrysler Corporate Quality Training Specialist Jim Crapko. There are many reasons e-learning or any training solution can fail. An objective assessment of the context for a learning solution is essential to identify some of the real barriers to success, and it is very likely that some changes will prove critical to success.

If we’re talking about employee training, for example, employees may not be doing what management wants because doing something else is easier and seems to be accepted. In this context, training focused on teaching how to do what management wants done may have absolutely no positive effect. It’s quite possible that employees already know full well how to perform the tasks in the manner desired, but they simply choose not to do so. The performance context needs to change.

Prerequisites to Success

An exhaustive list of e-learning success prerequisites is probably not possible, because so many factors can undermine an otherwise excellent and thoughtful plan. The items in the following list seem to be rather obvious requirements; yet, inaccurate assessments are often made about them:

- Performer competency is the problem.

- Good performance is possible.

- Incentives exist for good performance.

- There are no penalties for good performance.

- Essential resources for e-learning solutions are available.

It is not rational to ignore any one of these prerequisites and still hope for success, so let’s look closely at each one.

Performer Competency Is the Problem

It is crucial to understand business problems and define them clearly, if any proposed solutions are likely to address and solve them. Unfortunately, problems are often hard to identify. Perhaps this is because decision makers are too close to see them, or problems and their suspected causes are too hard to face. When pseudoproblems are mistakenly targeted, the real problems persist, ill-defined and unsolved.

Throw Some Training at It

It can be comfortable, even reassuring, to conclude that training is needed in the face of a wide range of problems. No one needs to be culpable for the problem. The prospect of a new training effort can paint enthusiastic pictures of problem-free performance. With high expectations, training programs are launched that have very little, if any, prospect of solving the real problem.

The error, however, is probably not what you’re thinking. It may actually be quite correct that people do need training for the ill-defined problems. Because the preponderance of business challenges involve human performance, a blind guess that training is needed will be correct more often than not.

The error is likely to be in deciding who needs training on what. For example, it may well be that supervisors of ineffective performers need training so they can more successfully draw out the desired performance from their already capable teams.

Nonperformance Problems

Businesses face many problems, of course, as I know from having started and run a number of them myself. There is a new challenge every day: higher costs than expected, slow receipts, telecommunication breakdowns, and so on.

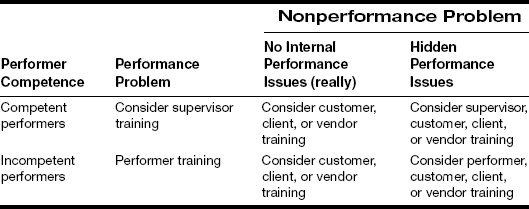

FIGURE 2.1 Misdirected training.

A question: You can solve business problems not emanating from employee performance with training. True or false?

Sorry, you’re wrong. Actually, this is a trick question. The correct answer is “sometimes.”

Here are two reasons:

- Most “nonperformance” problems, on closer inspection, include some performance problems.

- Not all performance problems can be solved with training.

The main point here is that training is a more broadly applicable solution than it may appear. Of course, training isn’t a good solution when there are no performance issues or when all players are fully capable of the desired performance. But think carefully. Are all players capable of the desired performance? Who are all the players? Training sometimes needs to be offered to suppliers, customers, buyers, and others. Think through the whole process. Again, it’s very important to accurately assess the situation—the whole situation (Table 2.1). Different answers may emerge.

TABLE 2.1 e-Learning Opportunities

On one hand, I often have clients planning a training solution when the problem doesn’t appear to be a performance problem at all. They aren’t aware of the true source of their problem, and the training solution they seek will be for naught. If the training proposed doesn’t address the source of the performance problem, it will be ineffective, no matter how good the instructional design and implementation are.

On the other hand, nearly all business problems are performance problems, at least in part. You must carefully examine performance problems to determine the root cause, or more likely, the root causes. It is likely that part of a good solution will be training. Generally, the questions are whose performance is the problem, and who needs training?

Go Ahead—It’s Easy

Easy to go wrong, that is. A sweeping order to put a new training program in place may yield welcome expectations that, as soon as it kicks in, problems will vanish. However, those receiving the order to go forth and train are set up to misunderstand what’s really important. Most likely, they will build a good-looking training program that trains the wrong people or trains the right people to do things that won’t actually help much with the identified problem. They were on the wrong path from the beginning.

Disguised Competency Problems

Many business problems not obviously amenable to training solutions can actually be addressed through e-learning, at least in part. Consider such significant problems as undercapitalized operations, outdated product designs, unreliable manufacturing equipment, noisy work environments, poor morale, bad reputation, and so on. Is training a fix? The somewhat surprising answer is that training should not be ruled out too quickly.

Although many factors determine the possible success of an enterprise, what people do and when they do it is the primary factor. If training can help change what people do and when they do it, then one component of almost every solution might well be training. Consider the following possibilities:

Undercapitalized operations.

Finding more money might not be the only solution nor the best solution. Achieving new levels of efficiency, offering better service, or redefining the business model to match available resources may be better solutions with or without new money, and all of these solutions probably require people to change what they’re doing.

If squeaking by without additional funding is the chosen route, it often means having fewer people covering more bases. To be successful, they need to learn how to handle a greater variety of tasks; just as important, they also must understand why they need to take on so much responsibility and what can be achieved if they manage well. Successfully squeaking by can be a business triumph if customer service is strong and customer loyalty is maintained. Could effective training separate the winners from the losers in your field when times are tough?

Outdated product designs.

How did this happen? Were people not tracking technologies, markets, or competitors? Did they know they were supposed to? Did they know how? Are they able to design better products? Perhaps some training is needed—the sooner the better.

Unreliable equipment or tools.

Is equipment purchasing ongoing? If so, do buyers know enough about your processes, needs, and cost structures to know the difference between a smart buy and a low price tag? If you’re stuck with the equipment you currently have, are there effective tricks or precautions known only by a few, maybe only by those on the night shift or by a few silent employees, that could be learned by others to make the most of your equipment’s capabilities? This could be a training opportunity.

Poor morale.

Poor morale isn’t just a condition, it’s a response. It can stem from a wide variety of problems or perceptions. At the heart is often lack of understanding, lack of communication, lack of trust, or conflicting agendas. Some good coaching and team-building exercises are probably needed. e-Learning may be helpful in some of these situations as an antidote to an acute problem, but it’s more likely to be helpful in ongoing measures that energize the workforce and safeguard against chronic morale problems. For example, the corporate mission can be communicated in ways that lead not only to knowledge of the mission, but also to energetic participation and endorsement of the vision. e-Learning can help management learn more effective ways of encouraging spirited contributions through listening, feedback, and appreciated incentives. Often improperly and narrowly viewed as a vehicle limited to the transfer of knowledge and skills, e-learning might overcome a lack of insight and nourish a sense of pride that restores or helps maintain the essential health of your entire organization.

Turnover and absenteeism.

People don’t feel good about themselves when they aren’t proud of their performance. They may be getting by, perhaps skillfully hiding their mistakes and passing more difficult tasks to others, but it’s hard to feel good about yourself when you can’t do well. As a result, it’s hard to get to work, and you’re constantly on the lookout for a more satisfying job. With the ability e-learning has to privately adapt the level of instruction to each learner’s need, it might just be a solution to problems of turnover and absenteeism.

Tarnished reputation.

Why does the organization or product have a bad reputation? Are deliveries slow, communications poor, or errors frequent? In the outstanding book Moments of Truth (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), Jan Carlzon shows how successful companies focus on the customer, the front line employees, and the interactions between them that define their respective companies through “moments of truth.” In an effective organization, “no one has the authority to interfere during a moment of truth. Seizing these golden opportunities to serve the customer is the responsibility of the front line. Enabling them to do so is the responsibility of middle managers” (Carlzon 1987, p. 68). But how do those on the front line know how to serve the customer? How do middle managers know how to support and guide the front line? Through e-learning? It’s a possibility.

Until a problem is identified and framed as a competency problem, e-learning is not the solution. The types of problems just listed are not the ubiquitous problems for which training is an obvious solution. They are listed to underscore the widespread, multifaceted nature of competency problems and the often unsuspected value e-learning can bring to corporations and organizations of all kinds.

Few problems are devoid of human performance difficulties, and, generally, few solutions without a high-impact training component will be as effective as those with it. Still, identifying the real problem is a prerequisite. Guessing about the problem is unlikely to lead to effective solutions. If e-learning is going to work, it’s necessary to determine quite clearly what the performance factors are and what is preventing the needed performance from happening. The problem may well lie in one of the other contextual inhibitors in our list.

Good Performance Is Possible

It doesn’t make sense to train people to do things they can’t do. It doesn’t matter whether people can’t perform because there’s never a case where trained skills are actually allowed or appropriate, or because it would take too long to complete a process if it were done by the book, or because appropriate situations occur so infrequently that it’s unrealistic to expect any trainee to retain learned skills between them.

I know that it seems too obvious to be included in this list of essential preconditions for successful e-learning, but there have been many times our consultants have looked at each other, shaking their heads in frustration, because they have realized that no matter how good the proposed training may come to be, trainees will not be able to live up to management’s expectations. Without changing the performance context, the desired behavior is not going to happen.

Training does not make the impossible possible or the impractical practical. Good performance needs to be a realistic possibility before e-learning has the potential to help. It’s common sense, but it needs to be mentioned.

Incentives Exist for Good Performance

Although the reasons aren’t always obvious, behavior happens for a reason. People turn up at work for a variety of reasons, but it’s safe to assume that most would not continue to appear if they were not paid.

Many people receive a fixed amount for the hours they work. They will not make more money immediately if they do a better job, and they will not receive less, unless they are fired, for doing a poorer job. So, for these people, pay is an incentive for being present and for doing a minimally acceptable job—and not much more than that.

Fortunately for employers, other incentives exist:

- Approval and compliments

- Respect and trust

- Access to valued resources (tools, people, a window with a sunny view)

- Awards

- Increased power and authority

- More desirable or interesting assignments

Because these incentives are consequences of desired behavior and are usually offered in a timely, reinforcing manner, they can and do affect behavior in profound ways. If valued incentives exist for desired behavior, training that enables such behavior is likely to be successful as well.

FIGURE 2.2 Ineffective incentives.

A partnership between management and training is critical for success (Figure 2.3). Management’s role is to provide a learning and performance context that results in a workforce willing to do what needs to be done, how it needs to be done, when it needs to be done. Training is responsible for enabling willing workers to do the right thing at the right time, to see opportunities, and to be effective and productive. The outcome is a win through a willing and able workforce.

FIGURE 2.3 Partnership of responsibilities.

When incentives do not exist or rewards are given regardless of behavior evaluation, personal goals take precedence. For many—certainly and thankfully not all—behavior-determining goals may become:

- Reserved effort (doing nothing or as little as possible)

- Increased free or social time

- Avoided responsibility

- Avoided accountability

Management may complain that employees are uncooperative, unprofessional, or in some other aspect the cause of operational failures. Seeing this as a performance capability problem, management might jump quickly to ordering up new training. Unfortunately, skill training for employees who lack incentive makes little, if any, impact.

Use Training to Fix the Performance Environment

By the way, e-learning may offer a means of improving the performance environment when positive incentives are absent:

- Consider training managers on how to motivate employees, seek input, build teams, or provide effective reinforcement.

- Consider providing meaningful and memorable experiences through interactive multimedia to help employees see how the impact of their work determines the success of the group and ultimately affects their employment. (Please refer to Chapter 5 to better understand how e-learning design can affect motivation.)

These solutions may be the most cost-effective means of getting the performance you need, and they will dramatically increase the effectiveness of training you subsequently provide performers working in the improved environment. Remember, of course, that you will still need to provide incentives for the people who receive training on providing incentives, or this training will also fail.

Blended Training Solutions

Consider these, also. Blended training solutions mix e-learning with classroom instruction, field trips, laboratory work, or whatever else can be made available. They can provide face-to-face interaction and the nurturing environment of colearners. Many believe the learning process is fundamentally a social process. Observing others, explaining, and questioning can all be very helpful experiences when other learners are working close by and at similar levels, have time scheduled for learning together, and are as concerned with depth of knowledge as developing proficiency as quickly as possible. In general, however, this is more of an educational model than a training model.

Nevertheless, just as it is important to provide incentives and guidance for job performance, it is also important to provide encouragement and support for learning. A well-nurtured learner is going to do much better with e-learning or any other learning experience than an isolated, ignored learner. Learning is work, too (although with well-designed learning experiences, people don’t mind the work—even if they should happen to notice it). Incentives, rewards, and recognition facilitate better learning just as they do any other performance.

Blended learning used to be more necessary than it is today, because computers and other instructional media were expensive and difficult to provide. Good interactivity was difficult to build, and media were often slow and of low fidelity.

Blended training solutions are once again in vogue. The reason, in many cases, seems to be that e-learning is not working as well as was hoped. Adding more human interaction to the experience is a quick and easy way to overcome some of the failure. It is perhaps too often argued in hindsight that e-learning just isn’t up to the challenge.

e-Learning isn’t the best solution for all learning needs. Few would argue that human interaction isn’t highly desirable in support of learning, but it is unfortunate to turn to blended learning as a coverup for poor e-learning. Many of the advantages of e-learning are lost in blended solutions, including scheduling flexibility, individualization of instruction, and low-cost delivery.

Blended solutions can be great. When done well, they can accomplish what no single form of instructional delivery can achieve. When done poorly, they stack e-learning failures on top of the disadvantages of other forms of instruction—and that’s not a win.

There Are No Penalties for Good Performance

We haven’t discussed avoidance of penalties as an incentive for good performance, although it is a technique many organizations rely on, even if subconsciously. Penalties are more effective in preventing unwanted behaviors than in promoting desired ones; but, over the long haul, they are weak even in doing this. Further, the burden of penalty avoidance (hiding out) saps energy and creates a negative atmosphere.

Although combined use of penalties (even if just verbal penalties) and positive incentives (even if just words of encouragement) is generally considered the most effective means of controlling behavior, employees will be drawn to work environments in which positive rewards are the primary means of defining desired behavior. They will tend to escape environments where censure is prevalent, whether deserved or not.

The worst case, of course, is one in which there are penalties for desired performance. While it may seem absurd that any work environment would be contrived to penalize desired performance, it does happen. In fact, I can—and, unfortunately, feel I must—admit to having created just such an environment at least twice myself. I offer an account here as both evidence that this is easier to do than one might think and as a small atonement for past errors.

Essential Resources for e-Learning Solutions Are Available

Design and development of good e-learning is a complex undertaking. It requires content knowledge and expertise in a wide range of areas including text composition, illustration, testing, instruction, interactivity design, user-interface design, authoring or programming, and graphic design. It’s rare to find a single person with all these skills, and even when such a person is available, training needs can rarely wait long enough for an individual to do all the necessary tasks sequentially. Forming design and development teams is the common solution, although teaming introduces its own challenges. (Chapter 4 identifies those and presents some process solutions.) What is essential in teaming approaches, however, is that all necessary skill and knowledge domains be included and be available when they are needed.

Not the Usual Suspects

Making sure all the needed participants are available and involved is not only a coordination problem, but also a problem of understanding who needs to be involved. For example, while everyone understands that subject-matter expertise is required, few executives see themselves involved in e-learning projects beyond sanctioning proposed budgets. But executives are presumably owners of the vision from which organizational goals and priorities are derived. e-Learning provides the means for executives to communicate important messages in a personal way that can also ensure full appreciation of the organization’s vision, direction, and needs, so it’s a major missed opportunity when executives have no involvement. e-Learning can truly help all members of any organization understand not only what they need to do, but also why it is important. Check Table 2.2 for suggestions on who needs to be involved when.

TABLE 2.2 Human Resources Needed for e-Learning Design

Executives |

|

Why |

When |

| The vision and business need must guide development. As projects are designed, opportunities arise to question and more fully define the vision—always strengthening, sometimes expanding the contribution of the training. Executives also need to see that posttraining support is provided. | At project definition to set goals. At proposal evaluation to weigh suggestions and alternatives. During project design for questions and selection of alternatives and priorities. During the specification of criteria and methods for project evaluation. |

Performance Supervisors |

|

| The people to whom learners will be responsible need to share not only their observations of performance difficulties and needs, but also help identify the interests and disinterests of learners and prepare posttraining incentives and support. | At project definition to propose alternative goals. During project design for questions and selection of alternatives and priorities. During the specification of criteria and methods for project evaluation. |

Subject-Matter Experts |

|

| Unless the instructional designers are also subject-matter experts, designers must have articulate experts to help define what is to be taught and to ensure its validity. | Throughout the instructional design process, beginning with prototypes and later for content scope determination and reviews. |

Experienced Teachers |

|

| If the content has been taught previously, those who have taught it will have valuable insights to share. They will know what was difficult for students to learn, what activities or explanations helped or didn’t help, and what topic sequencing appears to be best. | Throughout the instruction design process to help sequence content and suggest interactive events. |

Recent Learners |

|

| Recent learners are often the most valuable resource to instructional designers. Unlike experts, recent learners can remember not knowing the content, where the hurdles to understanding were, and what helped them get it. | During rapid prototyping, content sequencing, interactive event conceptualization, and early evaluation of design specifications. |

Untrained Performers |

|

| It’s very important to test design ideas before e-learning applications have been fully built and the resources to make extensive changes have been spent. Since you can only be a first time learner once, it’s important to have a number of untrained individuals for the evaluation of alternate instructional ideas as they are being considered. | During evaluation of second- and later-round prototypes through to final delivery. To add fresh perspectives, different performers will need to be added to the evaluation team as designs evolve. |

The more sophisticated the instructional design, the more likely it is that great amounts of time and money will be wasted if the creators lack a full understanding of the following elements:

- Content

- Characteristics of the learners

- Behavioral outcomes that are really necessary to achieve success

- Specific aspects of the performance environment that will challenge or aid performance

- Organizational values, priorities, and policies

In short, a lot of knowledge and information must guide design and development.

“Watson—Come Here—I Want You”

People must be available, not just documents. Other than having a too-shallow understanding of instructional interactivity, perhaps the biggest problem corporate teams have in producing high-impact e-learning applications is the lack of sufficient access to key people.

“Now!”

It is important not only to have the right people available but also to have them available at the right time. Otherwise, the project will suffer. A great many interdependent tasks are scheduled for the development of e-learning applications. They are far more complex than you can imagine if you haven’t yet been part of the process. If people are not available for needed input or reviews, it can be very disruptive, expensive, and damaging to the quality of the final product.

“Never Mind—We Have the Manual”

Repurposing is a term used to put a positive spin on some wishful thinking. It’s the notion that existing materials, designed for another purpose or medium, can be used in lieu of having more in-depth resources available for e-learning development. It sounds like an efficient if not expedient process to take existing material and turn it into an e-learning application, like turning a toad into a prince. It seems particularly attractive because key human resources, people who are always in high demand, should not be needed very much. The team members can just get the information they need from the documents, videos, instructor notes, and other materials.

Sorry. It’s a fairy tale.

Noninteractive materials are far too shallow to supply sufficient knowledge for e-learning design. You’ve heard the adage, “To really learn a topic you should teach it.” Preparation for teaching a subject requires much more in-depth knowledge and understanding than even the best students can gain from just taking a class. e-Learning approaches vary from timely e-mailed messages to fully interactive experiences incorporating dynamic simulations, but even the simplest form of interactivity tends to reveal weaknesses in the author’s understanding.

Repurposing is essentially a euphemism, because without additional content, in-depth knowledge, and design work necessary to create appropriate interactivity, repurposed material turns efficiently into ineffective electronic page turning. Any plan, for example, to take a manual and turn it into an effective e-learning application without the involvement of people knowledgeable in the subject, experience teaching the subject, and guidance from managers of the target audience is, if not doomed to failure, going to be far less effective than it could be. And, perhaps worse, the faulty applications produced may lead to the erroneous conclusion that effective e-learning solutions don’t exist, are too expensive, or are too difficult to build.

As you can see from Table 2.3, the materials to be created for effective instructional interactivity reach far beyond the information available in noninteractive resources. Much of this work requires in-depth content knowledge—more than can be gained from careful study of materials designed for declaration-based instruction.

TABLE 2.3 e-Learning Alternatives

| Alternative | ||

| Parameter | Repurposing | Designing for Interactivity |

| Base | Existing materials | Existing materials plus additional content and instructional experience |

| Design focus | Clear content presentation | Learner needs |

| Product potential | Page-turning application, possibly with shallow interactions | Highly interactive e-learning adaptive to learner abilities and readiness |

| Subject-matter human resources needed | None or little, depending on quality of existing materials | Extensive |

| Materials to be created | Content presentations structured for computer screen presentation and for transmission compatibility via chosen medium (intranet, Internet, CD-ROM, etc.) | Motivational material to prepare learners to learn Carefully structured learning events made up of learning contexts, performance challenges, activities, and feedback Logic to select appropriate events for each learner, given their individual readiness and needs Logic to judge the appropriateness of student responses Assessment events to measure the learner’s increasing level of proficiency |

In listing essential resources, it may indeed sound as though all e-learning applications are tedious and expensive. This isn’t true, but just as any organizational initiative should be guided by people in the know and with experience, it would be an error to attempt e-learning without the expertise needed to direct the effort.

Why Do We Do Things That We Know Are Wrong?

In outlining the contextual prerequisites in the preceding section, I worry that I’ve made an important mistake. I think the reasoning is logical, yet organizations repeatedly do things to suppress the success of their investments. My mistake may be twofold: (1) assuming that organizations will change their behavior if a better path is identified and (2) assuming that the overall success of the organization is the primary goal of individual decision makers.

The reality may be more like this:

- We like to fool ourselves. “We don’t like the costs we’re hearing for good e-learning applications. If we can get a project going with minimal investment, at least we won’t be completely behind the times—and who knows, maybe something really good will come out of it. I love getting a real bargain.”

- Our people are smarter than everyone else. “We don’t need to baby our people with all this learning rigmarole. Just get the information out to them, and they’ll do the rest.”

- It’s not really this complex. “I was a student once, and sure, some teachers were better than others. But pretty much anybody with a few smarts can put a course together.”

- Being conservative makes me look good. “I play it conservative. We don’t need Cadillac training, and I sure don’t want to be seen as throwing money around. I save a little, and we get some training. It might be pretty mediocre. But who knows? Everybody argues about training anyway, no matter how much we spend. So I look interested, and keep the costs to a minimum.”

It’s tough to fight such mentalities. The truth remains, however, that astute use of e-learning provides a competitive advantage. Many companies have completely changed their views of training. Whereas they once saw it as an unfortunate burden, they now see it as a strategic opportunity. They hope their competitors won’t catch on for a long time.

How to Do the Right Thing

It’s easier to point out errors than it is to prescribe failsafe procedures. There’s no alternative I know of to strong, insightful management. A short checklist with respect to e-learning would include:

- Make all needed knowledge resources available.

- Determine what’s most important to achieve and what the benefits will be.

- Look at ROI, not just expense, in determining your budget.

- Use designers and developers who have portfolios of excellent work.

- Define changes to the work environment that will build on learning experiences.

- Keep involved.

Design—the Means to Success

We’ve seen the importance of the design context for achieving training success and performance goals. Some errors are made by not using e-learning when it really could be of help. In other cases, training could not solve the problem, regardless of the approach taken. Finally, e-learning development, if it could otherwise be successful, is often held back by lack of access to critical resources.

When all the external factors are in place, we’re just getting ready to start. The challenge ahead is that of designing and developing a high-impact e-learning application. This is where the return on the investment of resources will be determined. The design, if you will, is yet one more element of the context that determines whether e-learning fails or succeeds.

In a process something like peeling away the layers of an onion, we will work down to the nitty-gritty details of design. We start first with questions of how good design happens.

e-Learning or Bust

There is an undeniable rush toward e-learning. The pioneering efforts in computer-based instruction of the 1960s have demonstrated the feasibility of outstanding education and training success, whereas e-commerce has fostered today’s expectation that electronic systems will be a primary component of nearly all learning programs in the future. People no longer wonder whether e-learning is viable, but rather wonder how to convert to e-learning most expeditiously.

There probably isn’t enough concern or healthy skepticism. It’s good if you are concerned about all this e-learning commotion. I’m there with you. I think it is good to be concerned because much (probably most) e-learning is nearly worthless. Just because training is delivered via computer doesn’t make it good. Just because it has pretty graphics doesn’t make it good. Just because it has animation, sound, or video doesn’t make it good. Just because it has buttons to click doesn’t make it good.

Excellent design is required to integrate the many media and technologies together into an effective learning experience. Excellent design isn’t easy.

Quick and Easy

Multiple approaches have been advocated over the years, and elaborate systems have been developed. Some have tried laying out more simplified cookbook approaches and providing step-by-step recipes for design and development of learning applications. Although all of them have provided many good ideas, the task continues to prove complex, as evidenced by the plethora of short-lived and little-used applications. Paint-by-numbers solutions just don’t hack it, although you wouldn’t know that from the number of people who continue trying to invent them.

There is an undying optimism that just around the corner is an easy way to create meaningful and memorable learning experiences that swiftly change human behavior, build skills, and construct knowledge. I am firmly in the camp that doesn’t think so. We don’t have automated systems producing best-selling novels or even hit movies. Developing engaging interactivity is no less of a challenge. In some senses, I see it as a greater challenge.

Clearly, tools will advance, and we will have more flexibility to try out more alternative designs faster. Our knowledge will advance, so first-attempt designs will be more successful than our first attempts are now. More powerful tools will help us evolve initial ideas into very successful applications. And perhaps, way down the line, computers will be able to create imaginative learning experiences on command. We’ll just access a database of knowledge, provide information about ourselves (if the computer doesn’t already have it), and indicate whether we want to study alone, with others nearby, or with others on the network. The computer will configure a learning experience for us, and voilà—there it will be! But not today.

Learning Objects

In the excitement of both e-learning’s popularity and our compelling visions of the future, many have been working to create approaches, if not enterprises, that expeditiously solve today’s problems and meet foreseeable needs. They hope to develop the primary catalyst that will bring it all together.

One instance of this is the concept of reusable learning objects (RLOs). An RLO (Table 2.4) is a small “chunk” of training that can be reused in a number of different training settings. RLOs are a speculative technical solution to reduce development costs. They address the technical issues of e-learning development and maintenance, but applying objects to all training situations can make designing quality training much more difficult. There are some unfortunate difficulties with RLOs that put their utility in question. For example, very small RLOs would seemingly allow the greatest flexibility, but because they are small, they carry minimal context and are therefore instructionally weak. As we’ve discussed, a strong context is needed for maximum performance impact. Context-neutral objects are generally undesirable learning objects, regardless of the number of times they might be reused. Larger RLOs, conversely, can provide essential context, but therefore need considerable revision when used in alternative contexts. Large RLOs tend to work against the fundamental purpose of RLOs.

TABLE 2.4 Reusable Learning Objects

| Characteristic | Pros | Cons |

| Reusability | They can be reused in different training situations. | Difficult to design training that will have the desired impact in several different training situations. |

| Standard structure | They are easier to use and lead to more rapid development. | Less flexible; instructional design must use an existing template. |

| Maintainability | Using templates and databases to store objects makes content easier to update and maintain. | Designers should not have to be limited to repurposed content; they should be able to create content that matches the context of that specific training situation. |

Is lowering the quality of e-learning a fair trade-off to ease maintenance? In some situations where content is changing rapidly and out-of-date materials are of little use, an approach that repurposes content is worth investigating. But poorly designed training that is easy to maintain is of little value.

Intrigue, challenge, surprise, and suspense are valuable in creating effective learning experiences. The drama of learning events is not to be overlooked when seeking to make a lasting impression on learners. Just as we have not yet seen automated ways to create such elements in other media, it will be a while before e-learning evolves to fulfill its potential. We still need to develop a greater understanding of interactive learning before we attempt to make courses by either automation or assembly-line production.

Art or Science?

A fascinating debate has been carried on among our industry’s most knowledgeable and respected leaders and researchers. The debate concerns whether instructional design is, or should be, approached as an art or a science. If based on science, then it should be possible to specify precise principles and procedures which, when followed properly, would produce highly effective e-learning applications every time. If instructional design is an art, then procedures remain uncertain, effective in the hands of some, who add their unique insights, and ineffective when used by others. It’s a lively debate in my mind, and I find myself in the frustrating position of agreeing with both sides wholeheartedly on many of their respective arguments.

I come out centered securely on the fence. It seems clear today that a combination of science and art is required and that neither is sufficient without the other. I believe the advocates of each position actually accept this centrist position in their practice.

No one can produce optimal meaningful and memorable learning experiences in a single pass of analysis, design, and development. Certainly experienced and talented people will do a better job than those with little experience or background. Although scientific methods are appropriate for the investigation of alternative instructional approaches, the science of instructional design is not yet sufficiently articulate to prescribe designs matching the impact of those devised by talented and, yes, artful instructional designers.

It seems that no matter how complex some theories may be—and some are bewilderingly complex—dealing with the complexity of human behavior overwhelms the generalizations of many research findings. By the same token, we need to draw heavily on research foundations to teach people the art of instructional design. Without the rudder of research, creative design results in applications that are simply different and unusual, but not effective.

Art + Science = Creative Experiments

Within each e-learning project, we are looking for ways to achieve behavioral changes at the lowest possible cost and in the shortest amount of learner time. Creativity helps us achieve these goals with just the right blend of content, media, interactivity, individualization, sequencing, interface, learning environment, needed outcomes, valued outcomes, and learners. Each of these components is complex, and the integration of them with others brings yet another layer of complexity. Each e-learning application is therefore something of an experiment—a research project in its own right—and creativity is needed to find an effective solution as quickly as possible.

This is not to say that each new application must be developed from a blank slate. Far from it; there is much more research and experience to draw upon than seems to be considered by most teams. An excellent compendium with interpretations for practical application can be found in Alessi and Trollip (2001).

Problems Applying Research Results

When research is considered, its message is often misunderstood and misapplied. Most problematic is the designer’s tendency to overgeneralize research findings. The temptation is to hastily apply theories without carefully considering whether the findings in one context apply to the present context.

When I have asked graduate students to justify various peculiarities in their designs, they could frequently and proudly cite published research findings. But in nearly every case, with a bit more analysis, one could see how the referenced findings can be valid and yet not support the graduate students’ design decisions. In many cases, one could go on to cite other findings that would suggest doing quite contradictory things.

Scientists are careful to address the applicability of their findings and to caution against overgeneralization. Researchers are continuing to look for principles that are broadly applicable and less dependent on detailed contextual nuances. While many advances are being made—most promisingly, in my view, through a collection of theories known as constructivism (Duffy and Jonassen 1992)—it is very important to realize that many appealing principles are far from universal truisms. It’s easy to make mistakes.

Valuable as scientific findings should be, it’s perplexing to me that so many who know research literature well cannot or at least do not design appealing and effective e-learning applications. If a pill tastes too awful to swallow, it will remain in the jar, benefiting no one. Such is the case with many e-learning applications too awful to swallow.

The problems appear to lie in two major areas. First, it’s important to keep not only the intent of an experience in mind, but also the likely assessment the learner will make of the experience. Is it meaningful, frustrating, interesting, intriguing, painful, confusing, humorous, or enlightening? Learners are emotional, just as they are intellectual, and emotions have much effect on our perceptions and what we do. In addition, adult learners are zealous guardians of their time. If they perceive a learning experience to be wasteful of their time, it is likely to become in short order exactly what they perceive—wasteful and quite ineffective. Irritation and resentment will build, attention will shift away as engagement fades, and the motivation to escape will take command.

It’s often noted that a high percentage of learners do not complete e-learning courses. Optimists say attrition occurs because learners quit when they have gotten all they need from a course. Because e-learning offerings are intended to assist people individually, learners should, in fact, opt out when they’ve gotten all they need. Of course, the more likely explanation for not finishing is that learners have had enough. Not all they need, but all they can stand. In their judgment, the benefits of completing the course do not justify the time expense or the pain of sticking it out. Harsh? I suppose. Reality? I think so.

Second, many common design processes actually prohibit successful creativity. In general, they crush inspired design ideas, rip them apart, and gravitate toward the mundane—all with an explicit rationale and justification to present to management and concerned stakeholders. It’s amazing how readily organizations complain about their lack of empowering training and yet find themselves structurally, mentally, and even culturally defiant against change and approaches necessary to get them to their beleaguered goals.

Chapter 4 discusses an effective process called successive approximation. It requires a dramatically different approach to application design and development, even though nearly all of the basic steps and procedures are found in every other formalized development process. It requires change, a new group dynamic, and managerial flexibility, but it’s worth it. It can make all the difference as to whether winning ideas will be discovered and incorporated in applications, or whether practicality will pronounce powerful insights dead on arrival.

A Pragmatic Approach

So if creativity requires guidance, and current scientific findings are helpful but insufficient, and the processes typically employed don’t get us the solutions we need, what can we do? We can take a pragmatic approach that depends on some creativity, intuition, and talent, to be sure, but also depends on experience as much as published research, intelligence, and an iterative process that includes experimentation and evaluation as fundamental activities. These foundations work well, but they work well only for those who are prepared and armed with the knowledge of how they work together.

The approach I advocate and will present shortly doesn’t drag you through a lot of research; there are plenty of available sources if you want that. What you’ll find here instead is:

- A frank, outspoken, impassioned, and blunt critique of what doesn’t work

- A list of conditions and resources essential for success

- A process that promotes error identification and rectification as a manageable approach to achieving excellence

- Examples of good design you can use

Get ready; all this is coming up next.

Summary

This chapter reviews a range of multifaceted situations in which e-learning might be a powerful component of a mission-critical solution, including some unexpected situations in which e-learning might be very helpful. It also presents a list of essential conditions for success:

- Performer competency is the problem.

- Good performance is possible.

- Incentives exist for good performance.

- There are no penalties for good performance.

- Essential resources for e-learning solutions are available.

Finally, this chapter shows that for e-learning, or any training solution, to succeed, it is essential that it be designed well—much better designed than what is typically seen—and this requires an investment of human resources going all the way up to the key visionary. If you are that visionary, you must be on guard, because people will let you down for many reasons (some of which are identified in this chapter), while doing what they think is best for the organization. You will need to invest the necessary time and resources to achieve your objectives, regardless of what the purveyors of technomagic would like you to believe.

The next two chapters address in detail the case for a systematic, iterative, exploratory approach to the design of e-learning solutions.