CHAPTER THREE

THE ESSENCE OF GOOD DESIGN

Excellent e-learning is a treasure that pays for itself over and over again. Each positive experience energizes, focuses, and enables yet another learner to be both more individually successful and more able to contribute to the organization.

Many traditional instructional design principles are either misapplied or used in justification of designs that simply do not work. They should be abandoned. It’s not my intent to start a religious war. I only hope to help free designers from a widespread bondage to some design principles that are frequently adhered to with something akin to religious fervor.

When we find that some things work over and over again, we should use them even if we don’t understand all the reasons why they work. Designers shouldn’t be hesitant to take nontraditional directions if they can see a possible benefit for learners. In other words, it is best to abandon traditional principles and methods in order not to abandon the primary goal of creating truly effective learning experiences. We should be guided by values, not habits.

I am somewhat irreverent in my treatment of many design practices and vote strongly in favor of on-target pragmatic approaches. What I value is learning experiences that are interesting, meaningful, and memorable, because they have the best chance of enabling people to do what they want and need to do. I hope you already share these values; if not, I hope to convince you that these values are most likely to return the success you’re looking for.

This chapter covers key design concepts at a high level, but in sufficient detail so that you will be able to specify criteria to be met by any e-learning application developed or purchased by your organization. It will also help you to judge whether a proposed design properly considers all the key issues and to recognize good and poor designs.

Design versus Technology

Excellence in e-learning comes not from the fact that it employs technology for delivery, but rather from how e-learning uses available media and the purposes to which it applies them. In other words, it’s instructional design that determines the excellence of any instructional experience, not the use of delivery technologies or lack thereof.

WHIZHEAD: Hey! Look at how I got that graphic to spin around!

YOU: That’s great, Whiz, but um, why is that spinning around, Whiz? Doesn’t all that commotion make it harder to concentrate on the key principles listed?

WHIZHEAD: We couldn’t do this spinning effect over networks until just now. I love these new software tools. Learners will think this is really cool.

YOU: Wouldn’t learners find it more useful to zoom in and inspect details?

WHIZHEAD: I don’t have time to do that. It took a while to get this thing to spin, and I think it’s cool! Don’t worry. They’ll love it.

Don’t mistake the appeal of new delivery technologies for good e-learning design. Good design, not the latest delivery technology, is essential to success. Good e-learning design is good because it effectively uses available technologies to make learning happen. It’s the design that will make the experience boring or inspirational, exhausting or energizing, meaningful or meaningless. It’s the design that creates value from the potential technology offers.

The Three Priorities for Training Success

Instructional design work provides many opportunities for designers to lose focus. This is especially true in e-learning, because its multimedia nature provides an endless array of opportunities for invention and artistic expression. The success of any training effort depends on keeping priorities straight and focusing efforts on those things that will really make a difference.

This is one topic within the great complexity of successful instructional design that is really quite simple and straightforward. Design success comes from doing just three things, and doing them well.

Ensuring That Learners Are Highly Motivated to Learn

Motivation is essential to learning because it energizes learner attention, persistence, and participation in learning activities. The concept is certainly not new to the literature of learning and instructional design (Keller and Suzuki 1988; Malone 1981), but, unfortunately, explicit treatment of motivation seems to be creeping into e-learning design plans only recently.

I’ve seen the wonderful effects of stimulating learner motivation, but there’s still much work to do before designers feel they can devote enough attention to this issue. Buyers of e-learning applications find it much easier to specify content coverage than to specify even a minimum treatment of motivation. As a result, explicit efforts to ensure sufficient learner motivation are often given only superficial attention, if any attention at all.

Spend wisely! In contrast to traditional thinking, I would suggest that if you have a very small budget, it may be appropriate to spend nearly the entire budget to heighten motivation. Highly motivated learners will find a way to learn. They will even be creative, if necessary, to find sources of information, best practices, and so on. They will support each other, exchanging information and teaming up to find any missing pieces. If your training program gets you only this far, you’ve probably already won the toughest battle. Now you can go on to make your performance solution more cost-effective by addressing the remaining two priorities.

Guiding Learners to Appropriate Content

Highly motivated learners are eager to get their hands on anything that will help them learn. In response to this motivation, it is important to provide appropriate material in a timely manner, before the motivation wanes.

There’s much more to this than meets the eye, and it’s not just the challenge of creating clear, understandable content—which does take expertise, make no mistake about that. Making sure content is appropriate for an individual learner means either providing excellent indexing (navigation) to help learners identify appropriate material, or applying an assessment that will determine what each learner needs and is ready to use. In either case, e-learning is often a cost-effective means of providing content access.

Providing Meaningful and Memorable Learning Experiences

Motivation and good materials are sometimes not enough to enable people to perform at the necessary level or to ready them fast enough. In many cases, there is a wide chasm between building motivation and providing good resource materials and achieving sustained performance competencies. Preparing effective learning experiences is then essential.

One can read extensively about delivering good speeches, handling a difficult customer, or managing a complex project, for example, but guidance and practice will still be necessary to reach needed levels of proficiency. In many cases, it is preferable for learners to make mistakes in a learning environment, where guidance is available and errors are harmless, rather than on the job, where thorough guidance may be more difficult to provide and errors could be damaging to people, equipment, materials, or business.

e-Learning—A Tool for All Three

It’s important to see e-learning as a means to an end, not as the ultimate goal. The three priorities just listed suggest a prioritized approach for effective e-learning application. First, e-learning provides the multimedia experience that can stimulate emotions, set expectations of success, and help learners visualize the meaning of success and the rewards that can accompany success. Second, e-learning similarly provides the multimedia and navigation components for communicating content to learners clearly and on demand. Finally, the interactivity and multimedia capabilities provide the essential ingredients for meaningful and memorable experiences.

Let me emphasize the importance of meaningful and memorable (M&M) qualities of learning experiences before we go on to specific design requirements within each of the components of e-learning.

Let me emphasize the importance of meaningful and memorable (M&M) qualities of learning experiences before we go on to specific design requirements within each of the components of e-learning.

Meaningful Experience

If a learner doesn’t understand, then that learner will not gain from the experience. This is instructional failure. Designers of single-channel deliveries for multiple learners, such as classroom presentations, must decide whether to speak to the least able learners (in hopes that other learners will tune in at the appropriate points) or target the average learner (in hopes that unprepared learners will catch up and others will wait patiently for something of value). The approach often results in many learning casualties.

Further, if learners don’t see the meaningful implications of learning prescribed tasks, such as the tasks’ applicability to the work they do or the advantages of new processes over the ones they currently use, the learning experience is also likely to be of little avail. When different learners perform different functions, it is important to help learners see the relevance of the training to their respective responsibilities. You shouldn’t just assume that they’ll see it.

Well-designed e-learning has the means to be continuously meaningful for each learner. It can be sensitive to learner performance, identify levels of need and readiness, select appropriate activities, and engage learners in experiences that are likely to be meaningful.

Memorable Experience

If meaningful experiences and the knowledge they convey are easily forgotten (as in a day or two after a posttest), or if learners don’t think to apply them in appropriate on-the-job situations, they might as well not have occurred. Time spent in training is expensive to employers. It is not usually the goal of training to simply give workers some enjoyable time off, only to return to the job with no improved abilities. Thankfully, e-learning has many ways to make experiences memorable, such as using:

- Interesting contexts and novel situations

- Real-world or authentic environments

- Problem-solving scenarios

- Simulations

- Risk and consequences

- Engaging themes

- Engaging media and interface elements

- Drill and practice

- Humor

Primary Components of e-Learning Applications

Good design is comprised of good decisions made both during the design of each primary component of the e-learning application and later as all the components are integrated to create the overall learning experience.

The primary components of e-learning applications to be designed are:

- Learner motivation

- Learner interface

- Content structure and sequencing

- Navigation

- Interactivity

We will review the critical role each component plays in creating effective learning experiences and cover the primary design principles applicable. To ensure success in e-learning and a positive return on investment (ROI), everyone, from responsible executives and purchasing agents to designers and graphic artists, should be aware of the issues involved and their importance for effective e-learning.

I hope the perspective given here will increase your ability to see design issues and options more clearly. I hope also that it will provide a useful perspective for assimilating the more detailed principles presented in Part 2, which revisits learner motivation, navigation, and interactivity design in finer detail. The many examples provided there suggest ways of achieving a wide array of learning outcomes. You might use these designs as a starting point for new application design.

My Guarantee

I guarantee that proper treatment of these essential design elements will make a difference in your success with e-learning, no matter how familiar or unfamiliar you are with research on human learning or instructional design. The approaches suggested here might be sufficient to help you produce much better than average e-learning applications even if you have no formal in-depth knowledge of the literature, although I truly don’t want to discourage you from knowing all you can about learning, perception, and assessment. Get into the literature if at all possible, but whatever you do, don’t overlook what I’m sharing with you here. These points are very important and ignored far too often.

Learner Motivation

You cannot learn someone. The challenge isn’t a grammatical one; it’s a logistical one. Perhaps, in fact, our language requires verb substitution—you can teach someone, but you can’t learn someone—in recognition of the fact that learning is an internal, personal, and ultimately individual act. It takes energy to learn—one’s own energy. Someone else’s energy can’t be used instead. Personal energy fuels essential activities of perception, recall, analysis, creation of meaningful associations, and storage of information.

With no fuel, it doesn’t matter how streamlined the design of your car is, how beautifully appointed the interior, nor how spacious the trunk. The car isn’t going to transport you very far. (Well, okay, maybe downhill for a short distance, but that’s it.) Similarly, it doesn’t matter how stunning your presentation slides are, how beautifully appointed the learning environment is, nor how easy it is to access great volumes of information. We don’t learn without focusing energy and activity on the task.

From observations of highly motivated learners, one can conclude that learning motivation:

- Releases the energy necessary to undertake learning activities

- Energizes the learner for learning

- Helps to filter out irrelevant stimuli that can hamper the learning

- Fosters recall of knowledge

- Encourages synthesis of new information

- Causes potential relationships to be considered and evaluated

- Builds and reinforces meaningful new relationships that will be stored in long-term memory

How Does Knowing about Motivation Help?

Think Backwards

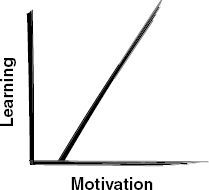

We evaluate teaching efforts by the level of their success in stimulating learning and achieving valued behavioral abilities. So let’s start with the outcome of desired abilities and see what is needed to achieve it (Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1 Thinking backwards, Step 1: Behavioral abilities.

Now, think what creates behavioral abilities. Teaching? Well, not directly. Remember that you can’t learn someone. If learning does indeed result, it isn’t because the teaching “learned” the learners. It results because learners do something; they do the things necessary to learn. So learner activity must precede the development of behavioral abilities (Figure 3.2).

FIGURE 3.2 Thinking backwards, Step 2: Learner activity.

We assume, by the way, that learning activity precedes changes in ability, regardless of whether the activity is externally observable. Internal neurological activity without external expression may be sufficient, but regardless of whether it is discernible, energized action is necessary to cause the biochemical changes that enable new behaviors.

Now ask what causes learner activity. In order for learners to undertake any voluntary activity, whether physical or mental, motivation must exist. By definition, motivation determines what we do with our time and summons the necessary energy. Motivation fuels learning activities, and maximizing it strongly predisposes learners to learn (Figure 3.3).

FIGURE 3.3 Thinking backwards, Step 3: Learning motivation.

Where does motivation come from? It comes from many sources, as Chapter 5, a full chapter focused on motivation, discusses. But for now, think of the voluntary intent to learn as a response to assessed needs, opportunities, and perceived rewards.

Teaching can influence how we perceive needs, opportunities, and potential rewards for better performance and therefore increase our motivation to learn (Figure 3.4). It can show us specific things that can happen once we’ve acquired certain skills. For example, a demonstration of good time management can show how just a few simple changes in daily habits can provide more quality time with our family and friends.

FIGURE 3.4 Thinking backwards, Step 4: Teaching.

The most effective instructional designs therefore deal explicitly with motivation enhancement. But good teaching also responds to the motivations and perceived needs it helps learners construct. It guides learners into and through meaningful and memorable activities that lead to targeted goals (Figure 3.5).

FIGURE 3.5 Thinking backwards, Step 5: Responsibilities of teaching.

It is a common but serious mistake to think of teaching as simply the presentation of information. It is a common mistake because, so often, teachers focus almost exclusively on the presentation of information. Yet teachers who are recognized as foremost in their profession are almost always cited for their creative invention of highly motivating learning experiences.

If teaching is to embrace the responsibility of building behavioral abilities, it is critically important that it center on ensuring adequate learner motivation to instigate learning activity and to provide the energy needed for the learning process (Figure 3.6).

FIGURE 3.6 Effect of motivation on learning potential.

No Mo, No Go

We can go through the traditional and expected steps of teaching, but without motivation, learners won’t learn (at least not much). Although with zero motivation there is arguably no learning, the relationship between learning and motivation to learn is probably a proportional one. The more motivated to learn one is, the stronger the focus and the greater the readiness to do what’s necessary to accomplish the task.

Recursive Rewards

Once in motion, of course, learners will benefit from appropriate guidance offered at opportune times. This too is a responsibility of good instruction. Without the support of good teaching to identify appropriate learning experiences, motivation must be all the higher for learners to essentially find ways to teach themselves.

Good instruction provides a double dose of help. It raises initial motivation levels and also makes learning easier by providing effective assistance. In turn, successful learning builds learner confidence and creates expectations of success, which increases motivation and makes subsequent learning activities more effective and easier to construct. The cycle repeats, nurturing itself and gaining strength. Getting off to a good start with maximized learner motivation has compounding advantages.

Motivation Levels Can Be Modified

When learners begin reading a book, enter a classroom, or start interacting with an e-learning application, their motivation levels are determined primarily by their initial expectations—expectations of what they will learn, its value, and how much effort is going to be required. They have expectations of how much they are going to enjoy or dislike the experience. They have expectations of whether they will do well enough to impress the instructor and fellow learners or whether they will struggle and possibly be embarrassed. Motivation levels are set by a complex interaction of many factors that no one is ever likely to understand fully—although, introspectively, we would agree that our expectations are largely responsible for our motivations.

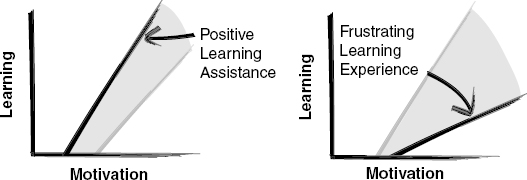

It Can Go Either Way

Fortunately, there are many things you can do to pump up a learner’s motivation; unfortunately, there are also many things you can do to shatter a learner’s motivation (Figure 3.7). Still more unfortunate is the tendency of e-learning developers to do more of the latter than of the former. This sad situation is probably the result of so much focus on what appear to be the primary challenges—technology and content—and not on what is really the challenge—behavioral change.

FIGURE 3.7 Learning experiences can affect motivation and learning.

This is not to say that technology and content aren’t important, of course. And it is not to belittle so many well-intended efforts. The attention both technology and content require can be exhausting, especially to newcomers who discover there’s so much more to developing learning experiences than meets the eye. Many just don’t have the time, money, or energy to get any further than their efforts to deal with content and technology. Ironically, when resources are limited, it’s probably better to start with what many never get to: motivation-enhancing experiences.

One of the characteristics of successful e-learning is that it doesn’t take motivation for granted. Rather, continued effort is made to stimulate interest, point out benefits, and confirm progress. While effort is necessary for learning, it doesn’t have to be unpleasant, monotonous, and wearisome work. Perhaps the adage “Work hard, play hard!” should be extended to “Work hard, play hard, learn hard!” Just as full involvement in work and play can be exhilarating, learning can be an invigorating and even addicting experience that provides lifelong benefits. Chapter 5 provides specific dos for designing learning experiences that raise motivation and specific don’ts for ways of avoiding motivation destruction. They may be the most important keys to successful e-learning I can share.

Learner Interface

A good user interface is difficult to achieve. Anyone who has used a computer knows that just to operate some of today’s most ubiquitous software you have to accept some absurdities (like clicking the Start button to shut down or ejecting a diskette by dragging it to a trash can). Poor user interfaces persist when people don’t realize how much better the interface could be or when the advantages of using a standard system outweigh the inconvenience and frustration of its poor user interface.

When I started working with computers in 1967, computers were designed for use by engineers or people formally trained to operate them, not by the general public. Programming languages assumed a mathemati-cian’s view of the world or at least a mathematician’s aptitude. Articulate use of a complex syntax was necessary even for the simplest tasks. Part of the fun of being a computer programmer was being a member of the elitist group that could make computers do things most people couldn’t. Specialized knowledge was indeed power.

The Interface Is the Computer

What people see of a computer is its external skins or interfaces—the keyboard, the mouse, and the options presented to them on the screen. Learners couldn’t care much less how the computer works internally or how much effort it took to build instructional applications. Rather, they care about what they can do through reasonable effort with their computers and how interesting learning exercises are.

The lack of greater technical knowledge worries many computer users, however, and they feel a continuing risk of doing something stupid—or worse, something damaging. Interfaces provided for controlling the machine often contribute to this sense of insecurity. With many interface designs, for example, users wonder if there are unknown options that could make their work much easier or simple ways to fix problems they are having. They suspect there are features they want, but they can’t find them and don’t know what they are called. So they muddle along somewhat anxiously within the realm of known procedures. Help systems frequently infuriate people as much as they actually help, and users resign themselves to working within a set of familiar features.

To be more productive and comfortable, people need interfaces that relate to how and why they use a computer. They need interfaces that make options clear and understandable, rather than hidden, unintelligible, and exasperating. Product designers continuously strive to meet exactly these goals in addition to providing efficiency and ease of learning. It is more difficult than it looks, but nevertheless an extremely important endeavor. A single interface weakness, just one, can lead to widespread user anxiety and discomfort.

Why should a single weakness have a far-reaching effect? Users look for patterns or conventions among controls and options provided. Conventions reduce the number of unique protocols that have to be remembered and usually provide helpful expectations of how unused options also work. The assumption users make is that the options work similarly to other related options or in exactly the same way as identically named options in other places.

When the consistency of conventions is broken in even a single instance, learners become uncertain about whether other conventions are also inconsistent. Every convention becomes immediately suspect. The software seems harder to use, confidence decreases, and many users barricade themselves within a subset of options that have proven reliable and at least minimally sufficient.

The Primary Responsibilities of Learner-Interface Design

Learner-interface design carries many responsibilities. It is not only supportive of interactivity, navigation, and information retrieval, but also integral to the success of all components of the e-learning application. It carries both the responsibilities of general user-interface design and special responsibilities to enhance the effectiveness of e-learning.

Briefly stated, the responsibilities of learner-interface design are to:

- Minimize memory burden. Except in cases of simulation, we are not generally interested in teaching learners to remember the details of the e-learning interface. Instead, we want them to use their learning energy to learn target skills. Learner interfaces should therefore be meaningful without having to memorize symbols, terminology, and procedures.

- Minimize errors. Good interfaces provide strong cues that help prevent errors. Learner expectations are properly set and reinforced by the interface, so that it’s not necessary to think carefully and behave cautiously.

- Minimize effort. Ideally, learners can perform each function with a single command, whether it’s a mouse click, keystroke, spoken word, or other quick command. Although such an approach may not be possible or might negatively impact other goals such as minimizing memory burden or errors, effort should be minimized as much as possible. Where different levels of effort are necessary, greater effort should be correlated with the learners’ perception of the computational task’s difficulty. That is, it should take little learner effort to get the computer to do something that seems quite simple, and more learner effort to command the computer to do something that seems difficult.

- Promote features. The learner-interface design has a role in reminding learners of features they can use. Hidden features obviously increase the memory burden and do nothing to promote features, but it isn’t always possible to keep all features visible. Frequently used features will be remembered most easily, so it may be appropriate to use unprompted commands for them while prompting for less commonly used features. Careful choices need to be made, as there are penalties for almost every compromise.

- Contribute to the learning process. The learner-interface design must do all it can to facilitate an optimally effective learning experience. The challenge is great, and every component must do its part. The ways of enhancing learning experiences are often context-specific. For example, if a machine process is being simulated, controls should resemble the controls learners will use. If learners are comparing documents, then it should manage selection and viewing of documents.

Overall, learner-interface designs should keep learners in control and able to communicate comfortably with learning applications. Although a little anxiety and discomfort can actually be helpful for learning, they should come from the learners’ desire to do their best and not from fear and frustration with the interface. Designers should always be concerned about learner comfort with the interface and must attend carefully to its psychological impact. We want to keep learners focused on beneficial learning activities and not on overcoming challenges in the interface.

Interface Creativity in e-Learning

Today’s development tools give e-learning designers great flexibility in designing user interfaces. Once learners have accessed an e-learning application, nearly all of what they see, hear, and can do is under control of the application. In many ways, this is great news—and quite worrisome at the same time.

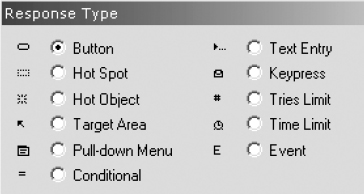

The Great News

The great news is that it’s possible to create an intuitive and comfortable environment for learners, even if they have little familiarity with computers. Options can be integrated into the interactive context to appear natural and recognizable. They can reinforce the effectiveness of the context as a whole. We are now more able than ever to devise highly “transparent” interfaces—interfaces that keep the focus on content and interactivity and do not drain attention or learner energy, yet are easily found and understood when needed. With an intuitive interface, fewer instructions are needed, and learners can engage in interactivity more readily (Figure 3.8).

FIGURE 3.8 Types of responses available in Authorware 6.0.

The Worry

The worry comes from the same fact that e-learning applications can define the learner’s interface to a great extent. The designer’s power to define and build interfaces goes to the head quickly. Different isn’t necessarily better, and divergence leads easily to the penalties inherent in undermining conventions. Application designers sometimes do things differently as a matter of expressing personal style, but their desire to be inventive doesn’t justify divergence. Interface design needs to provide utility and comfort for learners. Application interfaces should not be an unnecessary additional learning task!

Don’t Replicate Failures (Even If Everyone Else Does)

Computer environments are still not as easy to use as they could and should be. The last high point of computer–user interface may have been achieved when Apple Computer introduced its Macintosh computers with three primary software products, MacPaint, MacWrite, and MacDraw. The interface consistency, clarity, and naturalness in this trio of programs demonstrated that powerful operations could be learned quickly and easily by people having no prior familiarity with computers.

While many of the ideas introduced to the broad public through these products have been widely adopted and refined, many of them have also been compromised and perverted. As David Gelernter (1998) points out in his insightful book Machine Beauty (New York: Basic Books), there is a “relentless drive in the industry to complicate and featurize every piece of software until it keels over out of sheer brainless ugliness” (p. 132). We must combat this very real and present tendency in the design of e-learning applications if we are to succeed.

Jeff Johnson (2000), Ben Shneiderman (1987), Aaron Marcus (www.amanda.com), Donald Norman (1999), John Lenker (2002), and many others have shown us in their works and publications how things can be considerably better than they are. Often, when laid out clearly, principles of good user interface seem simple and obvious, yet good design is clearly not simple and obvious in practice. The evidence lies in the plethora of poorly designed software products, including major applications developed with vast resources. We’ve gone so far adrift that I even hear people say, “I haven’t tried any of those options. I couldn’t tell what they do, and I was afraid I’d get in trouble trying them.” Unfortunately, even having multiple levels of Undo can’t adequately protect users from the consequences of poor design.

Importance of Good Interface Design for e-Learning

If good user interface design is important anywhere, it’s critically important in e-learning. Why? It is a daunting challenge to get people to change their behavior, which may include changing habits, perceptions, and values, as well as acquiring knowledge and developing new skills. It’s less of a challenge if you have instructional design education, training, experience, and talent, but even for those select pros, it’s always a difficult challenge. To succeed, it’s important to gain a high percentage of the user’s attention.

Effects of Poor Interface Design

There are many ways poor user interface reduces the effectiveness of e-learning. Poor user interface can:

- Repeatedly and frequently distract the user’s attention

- Make text difficult to read and graphics ineffective

- Cause branching to the wrong information or exercises

- Confuse learners about their progress and their location within the application

- Make useful activities too bothersome to complete

- Obscure access to needed information

- Make comparisons difficult

- Slow interactions

- Debilitate feedback

Designs fettered by poor user interface have reduced learning impact. Learning energy is diverted to coping with uncertainty, mistakes, and frustration. Because it is a significant measure of success to achieve any behavioral change at all, few instructional applications can afford any reduction in impact due to poor interface design.

Content Structure and Sequencing

Defining what happens, how it happens, and when it happens is the essence of instructional design. The focus is generally on content—what content to include, how to use it, and in what order.

What Is Content?

Content is a term frequently heard in discussion of instructional design, but there are several common meanings (see Table 3.1).

TABLE 3.1 Alternative Definitions of Content

| Information-based | Content is all the information, such as facts, concepts, and procedures to be learned. A detailed outline, for example, would summarize the components. |

| Objectives-based | Content is a collection of learning objectives specifying behavioral outcomes. For example, “At the conclusion of this learning activity, students will be able to name four of the planets in our solar system.” |

| Media-based | Content is all the text, graphics, videos and other multimedia components of an instructional application. |

| Experience-based | Content is the sum of all instructional components in a learning application, including the learning objectives, media, interactions, and assessment activities. |

Who Cares?

Lack of a standard definition may not be a critical issue in itself, but it is clear there are many misunderstandings about e-learning—what’s good, bad, possible, impractical, and so on. Varying definitions of content may cause some of the misunderstandings, since assumptions of what a person means by content may be quite incorrect.

MANAGER: I can’t spend much on this training project. If nothing else, at least we need to be sure to present all the content as clearly as possible.

What did he say?

It depends on which definition of content is used. Those with an information-based definition would be thinking that the manager wants little spent on interactivity so that careful presentation of information can be accomplished, perhaps with good navigation controls. Those with an experience-based definition might well think the manager wants to make sure interactions are well chosen to teach essential behaviors.

Content-Centric Design

It makes intuitive sense that, if one can do no better, the content should be presented to learners as clearly as possible. Sometimes the simple presentation of information is sufficient to achieve needed behaviors, such as when:

- Learners are highly motivated.

- The information is readily understood.

- Skills can be learned without guidance.

- Each step can be prompted and guided as it is performed.

In other cases, however, content needs to be taught through meaningful and memorable experiences. It’s important not to mistake the two very different requirements of situations—those needing only the dissemination of information and those requiring training.

There’s a tendency to focus on content (information-based definition) and to judge training applications by how thoroughly they present information. The bias tends to work against objectively assessing learner needs and choosing an effective approach. This is no doubt because it is easy to judge whether information presentations are accurate, clear, and complete, whereas it seems difficult to appraise the quality of instructional design.

Content-centric design risks giving too little critical attention to essential attributes of the learner’s experience. It often looks at content structuring and sequencing from the subject-matter expert’s point of view, rather than from the learner’s point of view. Even when the learner’s point of view is considered, the design context is usually one of declaration and elucidation rather than a set of carefully sequenced activities that draw learners eagerly into skill-building exercises.

It’s not just nice for learning experiences to be interesting, meaningful, and memorable; it’s critical for success. Adult learners are ready to bail out as soon as they sense a waste of time, and younger learners respond similarly as soon as they lose interest. Content-centric designs can be a real turn-off for anyone.

Learner-Centric Design

The predigested, squeaky-clean content of content-centric designs is often prized and yet sometimes provides a true disservice to learners. Well-devised imbroglios can be fascinating and anomalies can be intriguing. Think of mystery novels versus textbooks. Which one more easily attracts readers?

Why is so much e-learning unmistakably and undeniably boring? Look to the level of design attention given to the learner’s experience versus the level of attention given to making sure the content is complete, clear, logically presented, and “properly” sequenced.

Completeness is not in itself interesting. In fact, it’s probably more boring than presentations that are full of gaps and require you to fill in the holes yourself. If you can and do indeed fill in the gaps and keep pace, you’re actively applying a lot more of your intellectual capabilities and gaining more from the experience than when you listen passively.

Learner-centric designs focus on creating events that continuously intrigue learners as the content unfolds. By providing tasks of approachable difficulty, you challenge learners to figure things out on their own. When they can, they are rewarded. When they can’t, aids are available.

After they complete tasks, learners are asked to put new skills and understandings in perspective. This might be done through a subsequent task requiring integration of multiple skills or tasks in which learners must choose appropriate procedures.

Repeatedly, learners are shown how each advance they make is a step toward realization of an important and attractive goal.

Content-Centric versus Learner-Centric Design Examples

Any time you are presented with a training challenge, you must determine which design is most effective. Let’s listen in as one of those decisions is being made right now. . . .

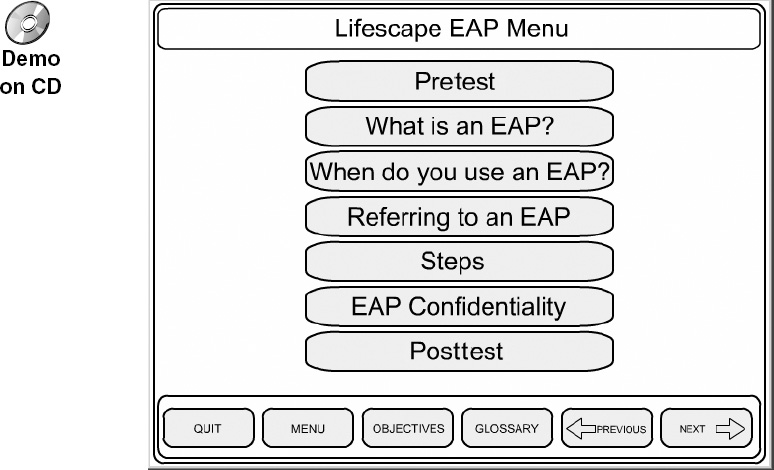

DECREE FROM ABOVE: We’ve spent a lot of money on these employee handbooks, and nobody’s reading them. The folks at our Employee Assistance Program (EAP) said that in the past six months, they’ve only received one phone call from us—and that was a wrong number. We don’t have a large budget, or a lot of time, so how can we get the message out there?

Content-Centric: The Classic Approach

WHIZHEAD: Hey, no sweat! It’s all in the book, right? So let’s put the book online.

We’ll start with a menu. The learner has full control! It’s totally interactive. [Figure 3.9]

FIGURE 3.9 A typical content-centric design.

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

We’ll put all the handbook information in each section, and add some nice graphics to it. They’ll want to scour every page. And check out that spinning logo. . . . [Figure 3.10]

FIGURE 3.10 A typical presentation screen.

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

YOU: Um, Whiz, how will we know the learner has actually learned anything?

WHIZHEAD: Oh, don’t worry about that—we’ll have a test! [Figure 3.11]

FIGURE 3.11 The obligatory meaningless posttest.

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

Learner-Centric: A Better Way

DESIGNER: What if we looked at this problem in a different way? The problem is that people aren’t using the services that are provided. That’s probably because they don’t relate to the EAP as a service they really need. No amount of reading the handbook is going to create that appreciation and intentions to use the service.

But what if managers were confronted with those tough situations first-hand? How would they react? Look at this approach. . . . [Figure 3.12]

YOU: Oh, poor Olivia. My mom died from cancer just a few years ago. I had trouble managing my emotions and responsibilities. What can we do for Olivia?

FIGURE 3.12 Your first simulated employee request: What decisions can you make to best help Olivia?

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

DESIGNER: Well, learners can talk to her coworkers to get more information. Or, they can check with Human Resources or the Employee Assistance Program to get helpful information tailored precisely to this situation. [Figure 3.13]

FIGURE 3.13 Checking available resources.

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

Once learners have gathered all the information they need, they make the call whether to document the issue, discipline her, or make a formal or informal referral to the EAP. They then decide whether to approve the bereavement leave. [Figure 3.14]

FIGURE 3.14 Time to make some choices!

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

YOU: Whoa, maybe we shouldn’t have referred her to the EAP so quickly. Seems that wasn’t the best choice. [Figure 3.15]

FIGURE 3.15 The results of your decisions—the good and the bad.

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

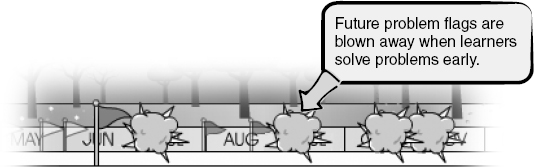

DESIGNER: Right. All of the feedback messages include the same information that’s in the handbook; only it’s more meaningful here. Most managers will be surprised that an immediate EAP referral in a case like this one is a bit insensitive and premature. How would they ever pick this up in a memorable way without an experience such as this? [Figure 3.16]

FIGURE 3.16 Good choices lighten your workload later on. Note the elimination of problem flags from the calendar.

Material codeveloped by Allen Interactions Inc. and the Multimedia Group at Lifescape, Sean York, director.

YOU: This is worth the investment.

Management or interpersonal development skills (often called “soft skills”) are training opportunities that defy traditional content-centric design. Every human resources department publishes employee policies and guidelines—but who reads them? The fact is, making good decisions to better the lives of your employees and maintain a legally compliant workforce is a tricky task; one that requires good critical thinking skills, because a poor decision made today could have drastic effects two months from now.

Clearly, this material could have been presented as a series of slides and a posttest, but how does that relate to your daily environment? Placing you in a real-life situation lets you more easily relate to the subject matter (meaningful experience), and you are more likely to remember the consequences of your choices (memorable experience).

In a program such as this, you might be tempted to make really, really bad decisions to see what awful things might happen. Great! What a wonderfully safe place to make those bonehead decisions so that you won’t make such errors in real life.

Learner-Centric Design Requires Commitment

Building great learning experiences often becomes onerous as deadlines approach and constraints seem ever more difficult to meet. Managers, designers, artists, writers, and programmers look fearfully at the constraints and scurry to provide content coverage—perhaps simply non-interactive text or some bullet slides. Many project stakeholders can be comforted knowing that all elements identified in a thorough content analysis are being presented. (After all, if the content is there, it is the learner’s responsibility to get something out of it, right? All the other things we might do would just make it easier for learners to get it. Give me a break.)

Again, it’s easy to determine if content is present. You just have to see it to know. It’s not nearly so easy to know if experiences are effective in building skills. So, when the pinch is on, content coverage often takes precedence over building critical learning experiences. It passes judgment, but fails in the long run.

Look for the M&Ms: meaningful and memorable experiences. You must include them. They’ll keep your designs learner-centered.

Look for the M&Ms: meaningful and memorable experiences. You must include them. They’ll keep your designs learner-centered.

Sequencing for Learning

There is a big difference between the structures of an encyclopedia, a textbook, and a course of instruction. The differences correspond to the different purposes for which they are designed.

Content-centric design and learner-centric design lead naturally to very different content sequences (see Table 3.2). For example, subject-matter experts, who naturally relate to content-centric designs, typically gravitate to one of three sequences—simple to complex, chronological, or hierarchical. These sequences are based on theoretical analyses of the content.

TABLE 3.2 Sequencing Models

| Content-centric | Simple to complex Chronological Hierarchical |

| Learner-centric | Known to unknown Misconceptions to latest techniques Goal decomposition |

Content sequences that appeal to experts may and quite likely will be confusing and overwhelming to learners. Even worse, they will be boring. Learners can’t appreciate clever or efficient organization of unfamiliar and meaningless information. They can’t appreciate the advantage of knowing terms for things they cannot yet recognize, value, or use. Nor can learners appreciate classification systems for meaningless items.

Learners are much more interested in knowing the value of what they are learning and how it will lead to meaningful abilities. Learners are interested in surprising facts, paradoxes, and effort-saving insights. In short, they are interested in how the content relates to them, rather than how the content can be systematically or logically structured. It’s there-fore important to use the relationship between each content segment and the learner as a guide to sequencing.

A Simple Approach

One way to do this is to help learners determine what they need to do in order to reach their performance goals. With guidance, “goal decomposition” exercises lead learners to identify the subtasks necessary to learn. Of course, this information could simply be presented to learners, but having them analyze the components of target abilities builds an individually meaningful learning map.

Learner-centered sequences:

- Determine the learner’s initial competencies and then build on them.

- Chunk content into a map of meaningful, performance-related events.

- Advance in steps meaningful to the learner, but not so gradually as to present no challenge or sense of reasonable progress.

- Allow learners to attempt almost any task at their request, including those that are probably too difficult; the results identify undeveloped abilities that learners can pursue.

- Allow learner-controlled review at almost any time.

Structuring Events

In building learner-centric e-learning systems, we want the learner to be an active participant—to be busy alternating among:

- Actively thinking about learning and thinking about the content

- Testing conclusions by working problems that will either confirm or refute learner hypotheses

- Practicing to strengthen skills and speed performance

We want learners at one moment to be thinking inductively to generalize their successes in specific, carefully chosen activities and to draw valid conclusions. At another moment, we want learners to be thinking deductively to determine from general concepts some specific principles—perhaps principles never actually presented or demonstrated to them. And finally, at other moments, we want learners to be rehearsing behavior patterns based on their learning.

For example, when learning mathematics, learners generally memorize specific math facts and procedures that, with familiarity, they begin to generalize so they can perform successfully on new problems (induction). At the same time, we want learners to grasp in some way the theoretical nature of mathematics—what it means to add two numbers—which will provide a way for them to develop math skills based on principles rather than arbitrary facts (deduction). And whatever behaviors the learner gains, mathematics will become memorable only by reinforcing skills and application of principles through practice. The challenge is to balance these three things appropriately for each learning situation.

Optimal content definitions for e-learning need to yield defined, purposeful learning activities. It is essential to define interesting events that conjure up insights, hold attention, and inspire behavior change. While theoretical organization, such as codification and clustering, may be compatible with this priority—and therefore advisable—the value of such approaches to structuring is secondary to creating engaging learning activities. Theoretical content organization does not justify mindnumbing learning experiences. (See Part 2, especially Chapter 5, for some easy and very effective means of structuring desirable learning events.)

Three Pitfalls

There are three prevalent pitfalls with respect to content selection and structuring that one must be vigilant to avoid. Consider the following:

- Giving insufficient attention to the learner’s perspective

- Teaching people things they already know—you will only irritate them by trying

- Teaching people things they can’t understand—you will only irritate them by trying

Let’s look at each of these precursors to boring learning events individually.

Giving Insufficient Attention to the Learner’s Perspective

It’s very hard to focus design equally on both content and learner experiences, although both are critically important. One of these perspectives will tend to lead—to dominate your thoughts and focus. Choose wisely!

If you work primarily for content thoroughness and clarity, you will end up with a very different product than if you center your focus on what the learner will be thinking, doing, and feeling. It’s important to let questions such as the following guide your thinking:

- What is the learner wondering?

- What challenges would increase the learner’s curiosity and increase his or her interest in participation?

- What common misconceptions does the learner probably hold?

- What does the learner probably know already?

- What do learners in the field aspire to?

- What in the desired performance looks easy, but is difficult?

- What in the desired performance looks difficult, but is easy?

- In what contexts does the learner enjoy learning?

Note that in answering these questions, applicable content is essential and can often be identified rather easily. Content will be identified in contexts that should enhance its appeal to learners.

Almost by definition, information that learners find boring is either information that’s meaningless to them or information they don’t see how to use. You can be assured that it will not be boring if you put new information and skills in a context that clearly reveals how they will help learners. Be sure to present the information and skills in a way that relates to what learners already know, and you will help to make it meaningful for them. Learners fairly want to know what’s in it for them.

Teaching People Things They Already Know—You Will Only Irritate Them by Trying

One of the precious powers of e-learning is its ability to individualize instruction—that is, its ability to fit the sequence of events and even the nature of the events themselves to the needs and readiness of each individual learner. The instructor-led classroom environment doesn’t have good capabilities for individualization. Teachers typically assume the role of presenting information to their students and leading activities. Unless all their students are identical in readiness and ability to learn, instructors have the challenge right from the start of simultaneously trying to reach those learners who have little background and need to cover basics thoroughly, and trying to pacify students who are already familiar with the basics and ready to move on. Even if they succeed in pacifying students who are essentially treading water, valuable time is lost in waiting for something beneficial to happen.

Most of us don’t enjoy putting our time under someone else’s control. If we’re not getting value for our time investment, we can easily move from disappointment to irritation and beyond. In short, the positive attitude of interest and readiness to learn can be lost in minutes if learning events appear to be of no value, either for learning or entertainment. Without an appropriate frame of mind, no learning occurs. Remember, you can’t learn someone. People must do the learning themselves. Try not to disable their abilities by boring learners to death.

Teaching People Things They Can’t Understand—You Will Only Irritate Them by Trying

The process of learning is a process of building. It’s a process of building associations between stimuli and responses. Most important, it’s a process that potentially results in a sustained change in behavior.

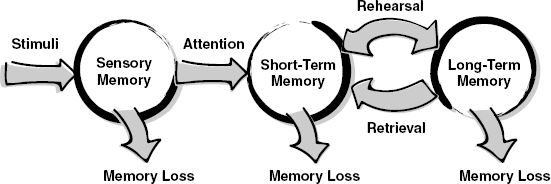

Although intellectual behaviors appear to be quite different from simple physical skills, similar underlying processes are at work in both instances. Theories suggest a process of learning which moves from perception to short-term memory to long-term memory (Figure 3.17; see Atkins and Schiffrin 1971).

FIGURE 3.17 The learning process.

Practice or rehearsal is necessary to move through the process, with increased practice leading to more permanent learning and behavioral change.

To begin the process, learners become aware of a relationship. If I said, “Say 1 when you see A,” you wouldn’t have much trouble. You have already learned to recognize the letter A. You know the number 1. Because both A and 1 are the first elements in symbol sequences known to you, the relationship is easy to build. A couple of quick rehearsals in your mind, and you’re ready to perform.

In many senses, the assignment to respond with “1” to the letter “A” is understandable to you. But what if I asked you to respond to a complex Chinese symbol that appears quite similar to other Chinese symbols for which I wanted different responses? Unless you’ve learned Chinese, you might have quite a lot of trouble deciding what response to give or even whether you had ever seen a particular symbol before.

Consider another case:

| Symbol | Response |

| A | 3 |

| B | 1 |

| C | 4 |

| D | 2 |

You would have the advantage of being able to recognize all the symbols and you would:

- Formulate a simple mental rule that all replies are numbers and all matching symbols are letters.

- See that numbers are matched to only one unique letter.

- Know that only the numbers 1 through 4 are being used.

- Know that only the first four letters of the alphabet are being used.

Although you would have to be mentally active to prepare yourself, there are many important structures you can observe about this task and many things you already know that would help you understand and perform it, even if the overall purpose of the task isn’t clear (which would add more understanding and make the task even simpler to learn and perform). The framework you can apply comes to your aid and makes this task a relatively simple one.

Okay, now suppose I wanted you to respond in a more complex way—by adding one to the base assignments (as listed previously) each time a letter was repeated. Sample correct responses would now be:

| Symbol | Response | |

| D | 2 | |

| C | 4 | |

| A | 3 | |

| D | 3 | Because 2 + 1 = 3 |

| C | 5 | Because 4 + 1 = 5 |

| C | 6 | Because 5 + 1 = 6 |

Further, suppose I did not explain this relationship at first, but would just correct you each time you gave a wrong response. You would be very confused. It would require many corrections before you could figure out what was going on. You would have a hard time learning, because the content simply would not make sense. In the process of trying to learn how to respond correctly, you might become quite upset. Your frustration might increase your attentiveness or it might make learning nearly impossible for you. If you just threw up your hands and thought the whole experience was poorly designed, you might just detach yourself and not even try. After a bit, you’d become thoroughly bored and look for ways to escape.

Although it seems ridiculous to imagine any learning situation in which learners wouldn’t be assisted with aids for understanding, they exist widely because of the focus on the organization and expression of content from the expert’s point of view. A learner’s perspective varies greatly from that of the expert, the business owner, the manager, or the trainer. Designers must account for variances in learner readiness and ability to understand, or they must face the very real risk that learners will have needless difficulty in learning and may actually become unable to learn because of their rising levels of frustration. Ironically, when designers let content drive design and use up their resources on meticulous presentation of the content, they neglect the very aspects of training that most facilitate content comprehension.

Try to avoid the preceding pitfalls. These three are common entrapments capable of snaring even experienced, vigilant designers.

Navigation

We can’t see all the content of an instructional application on the screen at one time (not that we would probably want to, anyway). Imagine taking all the pages of a book and covering a wall with them. After scanning over many pages and probably lingering over a few that appear to have the more interesting material, you’d realize that to get better value from the experience, you should pick a starting point and read at least a block of the material in the intended sequence. At the same time, however, you would appreciate having had the opportunity to appraise the total amount of material included, learn the book’s organizational structure, assess how many interesting elements there appear to be, and make some strategic decisions about how you might peruse it.

Books are much simpler in structure than e-learning applications. It’s easy to get an overview of them. Even before you’ve opened the cover, you have a sense of how many pages they have. You know if it’s a small, medium, or large book. Books usually have a simple linear sequence running from beginning to end. Yet to size them up, we find it very helpful to have titled chapters and sections, a table of contents, numbered pages, and a good index.

e-Learning applications are not so quickly assessed. You can’t even determine easily if they’re small, medium, or large. You can’t flip through them in a second to determine if they’re well illustrated, highly interactive, or truly individualized. In fact, you probably can’t determine very much at all about an e-learning application, except perhaps its style and general appeal, until you’ve invested a fair amount of time in it.

Learner Needs Addressed by Navigation

Navigation structures in e-learning serve many purposes, some identical to their counterparts in other media, some unique to the nature and capabilities of computer-supported delivery. Navigation is not just a bothersome necessity of less concern than the learning events. Some applications actually derive a great deal of their instructional power directly from the strength of their navigation.

Navigation in e-learning applications can provide many valuable services, including:

- The ability to preview and personally assess:

- Once into the application, the ability to determine:

- Overall, the ability to:

Navigation Can Help or Hinder Learning

It’s really frustrating to be uninformed and not know what to expect. Unless initial impressions are extremely positive, perhaps elevated by a fascinating opening (which I strongly recommend) or by reputation or trusted endorsement, people naturally become suspicious that lack of information means bad news. Expectations of a delightfully beneficial experience are replaced by doubt, if not dread. Not a good start.

Expectations set initial attitudes. Attitudes, in turn, assist or hinder the effectiveness of e-learning. With all the challenges facing us in the attempt to get people to do what we want them to do, a positive attitude is definitely something to foster. In many ways, all our efforts to shape behavior are much like processes of sales. We need to get people to want what we have to sell before we can expect them to buy. Constant focus and restatement of benefits is important. Navigation provides one of the ways people can pick up and examine our products and distinguish their benefits. It’s the packaging that can cause our product to go home with the learner or be put back on the shelf for later consideration.

As you can see, navigation in e-learning is far more than just getting from point A to point B. Navigation facilities provide a major component of the learning experience. Good capabilities not only enhance the power of presentation and interactive components, but also provide learning experiences directly by allowing learners to compare and research.

See Chapter 6 for more detail on navigation design.

Instructional Interactivity

The purpose of instructional interactivity is to wrestle our intellectual laziness to the ground—to reawaken our interest in learning, strengthen our ability to learn, and provide an optimal environment in which to learn.

Instructional interactivity is not the same as:

- Navigation

- Presentation

- Buttons

- Scrolling

- Browsing

- Information retrieval

- Paging

- Animation

- Morphing

- Video

These features are used, of course, in creating instructional interactivity, but they can and frequently are used for other purposes and in ways that do not result in the kinds of interactivity necessary to achieve success. Their presence does not signify instructional interactivity, nor the lack thereof, even though they are often promoted as evidence of interactivity.

Instructional interactivity creates not only external, observable events, such as clicking the mouse button or dragging an icon, but also (and more important) internal events, such as recall, classification, analysis, and decision making (i.e., thinking).

A Functional Definition

It is easier to note the results of interactivity than to define it directly, because the presence of typical interactivity components does not guarantee that true instructional interactivity is present. The essential concept of interactivity has to do with how the components are used. A functional definition that has value is this:

instructional interactivity Interaction that actively stimulates the learner’s mind to do those things that improve ability and readiness to perform effectively.

Beneficial Activities

In order to assist learners to build skills, we have to help them become active participants. We cannot do the learning for them; they must do it themselves. Further, choosing the most beneficial activity is not something learners always do well. Instructional design, therefore, involves both designing activities that result in learning and designing structures that attract learners to them.

To strengthen new skills so they can continue to grow and be useful, it’s important to exercise them—to apply them, to compare and contrast them with other procedures, to generate examples and counterexamples, to rehearse, and so on. Just as a physical trainer uses activity to keep exercisers moving, working at appropriate levels, and using reasonable but strength-building weights, interactivity is all about helping learners actively work at beneficial tasks. It’s powerful stuff when used appropriately.

The challenge is to use optimal learning events at the right times to achieve the best return on the learner’s time and our investment.

Using It Wisely

Failures are often blamed on inadequate funding, while successes are often credited to singular talent. Exceptional talent can overcome many obstacles (and a lack of funds can be a very uncompromising obstacle), but there are ways to produce very effective interactivity with average abilities and a limited budget, especially if one is careful to use interactivity where its unique capabilities have the greatest benefit.

Unique Characteristics of Interactivity

While multimedia is often used simply for fancy window dressing, interactivity is a technology which can take unique advantage of multimedia and create something far more valuable for our purposes than inactive books. Because books are learning tools with which everyone is familiar, let’s think one more time about books in contrast to the unique properties of interactivity.

Books are much simpler in structure than e-learning applications. They are not generally interactive at all, but as a reader, you can become active with the content in many ways. You can look away and see if you can restate for yourself what you have just read. You can recall instances in which the information you’ve read would have been helpful, would have applied, or might not have been possible. You can think about why you’re not doing what is suggested and what the consequences of changing what you’re doing might be. You can recall problems that have occurred and determine if the book is providing solutions.

Further, you can make flash cards. You can outline the content. You can quiz fellow learners. You can try role-playing. You can draw cognitive maps (sometimes called mind maps). You can invent mnemonics or stories that help you recall the components of sets or the order of steps.

There are many activities you can invent and undertake that will help you learn material presented in noninteractive ways. They take time, energy, creativity, and commitment. It also takes skill to do this effectively and efficiently. Not all of us are as good at it, and we certainly do not always do the best we can—nor do many of us do much of anything at all when we have to take the full initiative ourselves. Books and many other resources simply leave the activity up to learners. Sure, they might include some self-test questions or propose some helpful activities. But it’s very difficult, if at all possible, for books to simulate an active learning partner and mentor as computers can.

When questions are posed in a book, you can check the answer if it’s provided anywhere without having to commit yourself to an answer. When you see the correct answer, you’re likely to give yourself the benefit of the doubt and think, “Oh, sure. I knew that.” The question is, if you had been taking a test, would you really have been able to answer? Quite possibly not. If learners are left to judge their own competencies without the help of an objective measure, they are quite likely to err.

Consider working a crossword puzzle. If answers are provided, you can easily think to yourself that you really knew the correct answer, even when you discover the provided answer is different from your first thought. Funny how much harder those puzzles are when the correct answers aren’t there just to “confirm” your thoughts.

Interactions with the computer can force learners to commit to an answer or to perform a task before receiving feedback. Learners may be reticent to attempt a task, but it’s in their best interest to review what they already know and to apply their current skills to see how close they can come to the desired behavior. This helps us, as the instructors behind the electronic curtain, to continuously determine the learner’s current ability levels and select the next activity accordingly. Just as important, however, learners see what they can and can’t do for themselves. It sometimes takes a little adjustment for some learners, but with well-designed interactivity, learners quickly come to see the advantages of being able to make mistakes and learn from them in privacy.

Good instruction:

- Causes learners to think

- Helps learners synthesize new information and integrate their knowledge

- Helps learners rehearse skills and prepare for performance

- Promotes awareness of competencies, readiness, and needs

- Contributes to self-confidence.

Good e-learning accomplishes all this and can also help learners:

- Learn privately from mistakes without public humiliation

- Experiment to see the effects of poor decisions or poor performance

- Explore in response to individual levels of interest

- Test their knowledge whenever they might like a progress check

Making Good Interactivity Happen

Chapter 7 takes up interactivity in detail. It looks at the anatomy of good interactions, identifies their components, and looks to see how they integrate to achieve the important learning events of which they are capable. Examples are provided so you can personally experience the power of interactivity.

Next up, however, Chapter 4 turns to the overall process of designing and developing applications sporting the full magic of well-designed e-learning methods. Traditional processes attempting to deal with the complexities of learning application design and development have been tedious, often resulting in considerable friction among players, such as between subject-matter experts and instructional designers. Unfortunately, all the strife and long hours of work rarely achieve the kind of powerful and fun learning experiences we’re talking about here. Happily, I have a new, better process to share with you. It overcomes many of the traditional problems while fully embracing the need to be learner-centric.

Summary

Good design is essential for success but uncommon in e-learning. Perhaps this is because teaching is confused with presentation of information or perhaps because so much attention is given to technology that little remains for dealing with instructional concerns. Whatever the reason, good design can’t be achieved without careful attention to learner motivation, user interface, content structure and sequencing, navigation, and interactivity.

Motivation is often not directly considered or addressed at all in designs. User interfaces often distract and frustrate learners. Content is often structured for completeness or logical sequencing without regard to making the learner’s excursion through it meaningful, compelling, or even interesting. Navigation is often confused with interactivity and yet fails to provide user support that makes e-learning comfortable and convenient. Finally, the precious powers of interactivity are often not enlisted to either challenge learners or demonstrate their advancing proficiencies. Clearly, there are missed opportunities.

Part 2 takes up these design issues in detail, but for now, we have identified the issues. The next chapter deals with the process of identifying needs and creating solutions. The proposed process breaks with traditional methods in some important ways. It does so in recognition of the added complexity of striving not only for accuracy and clarity, but also for highly motivating, meaningful, and memorable events.