Chapter 4

What Is Music?

Introduction: What’s in a Name?

It is the essential uniqueness of human experience, our perception of time in particular, that makes our insistence on defining the word “aesthetic” as “how we perceive the world through our senses” so critical. Each of us perceives the world differently, first because of the uniqueness of our eyes and ears, but more importantly, because of how our brains process the information provided by those senses. And while there is a lot to be said for playwright José Rivera’s description of theatre as “collective dreaming,” we must acknowledge that only the stimulus is the same for each audience member1 (Svich 2013, 47). What happens inside each person’s brain is undeniably unique and different. Later in the book we will discuss how we combine the “collective dreaming” experience of theatre with our own experience to create a unique perception, unlike that of any other audience member.

It makes less sense, then, to evaluate a work of art as good or bad for anyone other than one’s self. Whether we are singing along with a crowd of 100,000 people in Chicago’s Grant Park to Coldplay or huddling together in a small community theatre laughing at a Neil Simon comedy, each one of us experiences something different. For some of us, the experience may be profoundly moving; others may wonder how quickly they can hit the exit. But we humans are social beings, and we crave shared experiences even if we know that we’ll never experience an art work in exactly the same way as another audience member. The best we can hope for as artists, then, is that we provide an experience that a large enough group of people find meaningful or fulfilling in some way. Unless we are creating just for ourselves, we will probably want to avoid creating an experience to which no one relates.

So how do we create such an experience? How do we ensure that our audience will contain enough individual members, each having a sufficiently positive experience to justify our creating the art work in the first place? In the last chapter, we cited Rozik’s assertion that the difference between dreams and theatre is that theatre is “communicative.” That turns out to be a tricky description. To communicate means to convey information, to reveal something using “signs” (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, 2015). Such communication is certainly a major part, and for many, the point of the theatre experience. However, communication is a very different experience than suddenly finding yourself immersed in the dreamlike world of a play. Sure, your conscious brain can consider the ideas of the play as a spectator. But there is another part of your brain that becomes so immersed in the story that you feel that the events happening in the play are actually happening to you.

And that’s the part of the play on which we are going to focus in this book: the parts involved in immersing and transporting the audience that include manipulating emotions and temporal perception. It will be hard to describe this as “communicating”; to use that word invites confusion with the words, images and ideas used in communication. As the noted neurologist Oliver Sacks was fond of saying, “music doesn’t have any special meaning; it depends on what it’s attached to” (Sacks 2009). Of course, we prefer to think about it the other way around. This book is about music, and the things we attach to it. Rather than describe music as a communication, we will use terms like “incite,” “arouse” or “immerse.” We will often accomplish such arousals and immersions through largely unconscious processes, not through the communication of ideas (although certainly not exclusively). The experience of music in theatre, we will discover, carries communication. It is not the communication in itself.

This may be a hard concept for many to understand. Hopefully this concept will become much clearer as one moves through this book. Many will argue that music is itself a communication, depending on one’s definition of communication. Certainly, elements of performing, transmitting and listening to audible music may possess elements of communication. For example, we listen to a performer, and immediately recognize that the performer is playing a guitar. If we are musically trained, we might recognize that they are playing a C major chord. However, these elements of communication are not what we are primarily interested in when we experience music in theatre as an audience member. We are more interested in how music affects our “soul” (whatever that is). In this book, we need to separate the communicative elements of performing and analyzing music from the more immersive experience we have when we use music to transport us into the world of the play.

We must agree from the very beginning, then, that how we define and use the term “music” will be very specific to our purposes in this book. There are enough definitions of music floating around in the world to make your dentures float. Creating one to help you specifically understand what we mean when we use the term in this book should not cause problems for anyone who speaks the English language. Most words have several meanings—Merriam-Webster lists five just for the word “music.”2 We are all quite familiar with using the definition of a term most appropriate to a particular discussion. In this book, then, any time we use the term “music” from here on, we will mean the definition we develop in this chapter, and we’ll just agree not to argue about it, because we know that music can have many, many definitions. After you finish reading this book, when you go out and you talk about music elsewhere, I don’t have any intention of forcing this definition on you. The only reason we need to have this definition is so we can have a conversation in this book and all be sure we know exactly what we mean when we use the shortcut word “music.” Of course, you are welcome to wander through the rest of your life using the definition I’ll lay out in this chapter. It would be an honor to have you absorb it as part of your aesthetic.

We’ll start with Edgar Varèse’s definition of music as organized sound. We’ll add on to that Rodriguez’s insistence that music is a temporal art (big surprise, eh?). We’ll separate the unique power of music to stimulate us from the ideas that words and images communicate. Then we’ll add an interesting twist that you might not have seen coming: music is also a visual art. Finally, we’ll break music down into its component parts—energy, time and space—so that we can more carefully understand what music is and is not. If we make it through all that OK, we’ll be ready to propose a definition of music. If we can all agree that this definition is what we’ll use throughout the rest of this book, we’ll be ready to begin to explore our main thesis: that music is the chariot that carries ideas into the deepest part of our mortal coil.

Music Is Organized Sound

So let’s define the term “music,” because quite frankly, everybody has a different idea of what music is—my parents in particular. I know because they were always yelling at me, “you call that music?” That’s my whole life.

Edgard Varèse was an early twentieth-century French composer. He was among the first to explore electronic music and move away from composition that employed traditional musical instruments. He famously proposed a very simple definition of music: “organized sound” (Varèse and Wen-Chung 1966, 18). This definition is good, because it allows for non-traditional sonic stimuli (e.g., synthesis, ambient sound, musique concrète). It is liberating; it frees up the imagination to think about composition in whole new ways, and begins to suggest a bridge between the terms “music composition” and “sound design.” It’s a bridge that I have crossed many times. So many times, in fact, that I have ceased considering the two terms, composition and design, to be functionally different. If you are truly interested in this discussion, compare the definitions provided by Encarta at the end of this chapter!3

In 1976, I proposed a similar definition of theatre sound design as simply the “organization of the aural experience of the audience” (Thomas 1980, 3). I proposed this definition in order to challenge my colleagues and students to consider sound in theatre as a holistic experience. This definition makes it clear that everything an audience hears when they come to the theatre is a part of the sound design. This, of course, includes the music, sound effects and sound reinforcement system. But it also includes the actor’s voices, the hum and noise of the air conditioning system, and even the audience’ noises, both desired and undesired. Sound design, I suggested, was a very broad term; composers and sound effects technicians were sound designers, as were directors, playwrights, actors, acousticians, architects and audience members—especially those who coughed during the quiet parts.

Scene designers were sound designers, too, as they had a lot to do with how the sound transmitted from the stage to the audience. Unfortunately, they also often contributed to the cacophony of unorganized sound as the scenery rattled and rumbled unintentionally on its journey through space. Equally unfortunate were lighting designers who often added to the unorganized din, first with static lighting fixtures that just rattled and buzzed, but then with moving light fixtures that whirred and hissed and clacked and swiveled.

Lest anyone think that I’m overreacting here, let me convey a quick story about an experience I had at the 2002 London Sound Colloquium hosted by my friends Greg Fisher and Ross Brown. They had invited the gathered guests to a final preview of Bombay Dreams at a prominent West End theatre. I found myself seated next to a very prominent British sound designer. The curtain went up, the moving lights exploded in their signature sonic clatter, and that sound designer sitting next to me exploded in a most unexpected clatter of his own. He jumped seething into the aisle ranting about how moving lights were destroying theatre and I thought for a moment he was leaning toward violence. Understandably. When you increase the noise floor, you distract the audience, and you also decrease the amount of room between the actors’ vocals and the noise floor where the composer’s music needs to fit. As far as he was concerned, the unorganized sound was ruining the organized sound.

At any rate, I became quite fond of challenging students in my sound design classes to explain the difference to me between the word design and the words compose and composition, especially if music was “organized sound.”

“Well, music composition has notes and instruments.”

“What about musique concrète?”

“OK, sound design is meant to support something else like a play.”

“Tell that to Danny Elfman.”

“Well music starts from nothing and sound design uses things that are already in existence.”

“So, you build the instruments before you play them then?”

“Composition has less of a reference than design.”

“Maybe, maybe not. Depends on what’s attached to either.”

And so it goes on and on. I’m not just being cranky here. I have simply found in my life, in my aesthetic, that I can use the terms interchangeably, and I always mean they are synonyms for each other, they mean the same thing. It will be a lot easier, then, when I talk to you in this book, that no matter which term I use, you will know that I also mean the other. For me, design and composition are synonyms, they’re the same thing; design and composition are nouns, and design and compose are verbs.

Oh, and by the way, I should note that my parent’s complaints about my tastes in music were often related to artists such as Frank Zappa playing “Help I’m a Rock.” Zappa, as it turns out, was perhaps Edgar Varèse’s biggest fan. I guess I’ll stick to the standard answer I always gave to my parents: “Yes, I do call that music!”

Narrowing Our Definition of Music

Another oft-cited definition of music, and one that you may guess is near and dear to my heart, is composer Robert Xavier Rodriguez’s 1995 assertion that “Music consists of sound organized in time, intended for, or perceived as, aesthetic experience” (Dowling 2005, 470; Rodriguez 2016). Near and dear, first because it identifies music as a time art.

Michael Thaut summarizes this unique quality of music even more emphatically:

One of the most important characteristics of music—also when compared with other art forms—is its strictly temporal character. Music unfolds only in time, and the physical basis of music is based on the time patterns of physical vibrations transduced in our hearing apparatus into electrochemical information that passes through the neural relays of the auditory system to reach the brain. (…) Music communicates critical time dimensions into our perceptual processes.

(2005, p. 34)

Rodriguez’s definition is also significant because it acknowledges the uniqueness of our perception of music as aesthetic experience, although Rodriguez most likely refers to the more modern definition of aesthetics, which concerns itself with “the nature of beauty, art and taste” as Merriam-Webster puts it (Merriam-Webster 2017). In Varèse’s definition, a conversation in a grocery store could be considered “organized sound.” Rodriguez helps clarify that music is somehow a separate temporal experience specifically related to art. While we certainly risk getting bogged down in an endless discussion of “What is art?,” it does seem like it’s a good idea to confine our definition to artistic endeavors, rather than any old organization of sound at all.

Both Rodriguez and Varèse’s definitions have another problem that fundamentally undermines a key concept about the nature of music. Both definitions allow the inclusion of the language used in poetry. Neither separates the musical elements of poetry, such as rhythm and dynamics, from the ideas communicated by the words in poetry. Curiously, this is exactly how Plato defined music in his Republic, which we will come back to in Chapter 12 (Republic, p. II). For now, we should just content ourselves that Plato came out of a world in which his predecessors considered mousike to pretty much include all time arts, including history and astronomy, literally the arts inspired by the Muses. Aristotle, on the other hand, made a distinction between music and song, that is words with music (Poetics, Section I Part VI)—just like we will do in this book.

Why do we need to make such a distinction? Because an important part of this definition, of our whole approach, is understanding the key differences between word/images4 and music. Music is largely devoid of semantic meanings, but has this magnificent power to incite emotions and manipulate our perception of time. Later we will discover evolutionary and biological evidence that will also support teasing out these differences between word/images and music. In order to understand those differences and how they impact our perception of music and theatre, we must define our terms in a manner that clearly identifies these differences.

Fortunately, there is another neuroscientist, Ian Cross, who conveniently defines music with just such a distinction: “Musics can be defined as those temporally patterned human activities, individual and social, that involve the production and perception of sound and have no evident and immediate efficacy or fixed consensual reference” (2003, 47). Now that’s really getting us somewhere. First of all, Cross also confines his definition to temporal activities, which is hugely important. Music is about time, about the organization of time. But Cross really gets to the heart of the matter when he says “no … fixed consensual reference.” Music exists on its own; it doesn’t refer to anything else. It’s not a semiotic kind of language full of meaning; there are no signs or symbols inherent in music. It is what is. Others have tried to attach ideas to music. For example, the Romantics tried to create music that told stories, but, of course, they were horribly unsuccessful at it, because everybody has a different story going on inside their minds when they listen to such music. At best, program music such as Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique only communicates specific meanings because Berlioz attached written “program” notes to the music, thus telling the audience in referential words the images the music should have put into their heads all by itself (Berlioz 2002).

Language is really good at communicating ideas. Look at all the books there are that communicate ideas, some of them even brilliant ideas. Images are also really good at communicating ideas; even a simple stream of emojis can communicate a lot. Music contains no such references. Music consists of completely non-referential elements such as pitch, tempo, rhythm and loudness. When you hear a certain tone, you don’t go “oh Cleveland.”

That isn’t to say that sound is not capable of generating images; a dog bark pretty much sounds like a dog barking! Sound does have some ability to refer to things in the real world; it just winds up being very poor at it. Many sounds are hard to distinguish from other sounds. “Is that rain or bacon frying?” Many sounds are hard to identify at all. “What’s that squeaking sound?”

Language is really good at communicating ideas, and images—pictures, as we said before, are worth a thousand words. It doesn’t make a difference whether a word is printed or spoken. The printed word “elevator” doesn’t look like an elevator, and the phonemically pronounced word “elevator” doesn’t sound like an elevator. It’s just a symbol, but we all agree when we see that word or hear that sound, we mean an elevator.

It is these word/images that refer to things in our external world that we want to isolate out of our definition of music. Music, as Stravinsky famously said, “is powerless to express anything at all…. Music is the sole domain in which man realizes the present” (Stravinsky 1936, 53–54). Music doesn’t simply tell us about emotions; it incites them, creates them in the present moment, first in the musician, and then, hopefully in the audience member. We’ll start to get to “how” in the next chapter.

To help illustrate this point, consider again the sentence, “I’m going to the store” from Chapter 1. Language communicates the referential idea that I, Rick Thomas, am going to a place where merchandise is offered for retail sales to customers. But what about the musical elements of that sentence? Just looking at those five words on the printed page, there doesn’t seem to be a whole lot of music there. The words on the page do not communicate how I feel emotionally about going to the store. That’s the job of music. Even if you put your hand over your mouth when you say the words so that you can’t understand them, you’ll still hear the elements of music, loud and clear.

Music Is Visual as Well as Audible

We’ve just seen that sound can have referential meaning, for example, a train whistle that signals its approach readily refers to something we recognize in the real world. Play a train whistle sound and ask just about anybody what that is, and they will tell you “a train” (unless they’ve not had experience with the referent, of course!). Not all sound is music, and some sound can serve a dual purpose of both being referential and musical.

It should not surprise us then, that visual art also has a musical component. It’s clearly not all referential. One reason this should not surprise us is that we’ve already discussed the eyes’ perception of time as a secondary ability, next to space. As a secondary ability, we won’t necessarily expect visual music to have the same capability as sound. Audible music has features not shared by either language or visual communication. For example, Thaut points out that audible music has the properties of being both sequential and simultaneous (Thaut 2005, 1–3). Audible and visual music are both sequential, meaning that their events unfold linearly in time, but audible music is also simultaneous, meaning that we can perceive multiple sounds simultaneously and individually, and within some psychoacoustic limitations, can focus our mind to concentrate on one sound while another occurs simultaneously. Without this feature, we would not be able to experience the piano, bass, drums and guitar of a jazz band simultaneously. We wouldn’t even be able to experience the harmonies created by the simultaneous melodic lines in a Bach fugue.

In visual color, when we combine colors, we perceive a new color, not the individual colors. In order to perceive individual properties, we need to move our eyes sequentially from a space where one color exists to a space in which the other color exists. Language, as Thaut reminds us, is also “monophonic,” in that we can only concentrate on one conversation at a time, just as we only see one thing at a time (2005, 1–3). That “monophonic” quality is great for communicating ideas, and word/images, but it’s the simultaneity of music that really is so special and unique about the experience of music.

Thaut also observes that since our eyes move as we engage a static art work, such as a painting or a sculpture, there is an implied musical sense of time based on how our eyes move to perceive the art work. How much Michelangelo directs the movement of our eyes when we view the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is debatable; certainly he would not be able to control when and where we start looking, how fast and in what direction we move our eyes once we start looking, when and where we stop, and so forth. So there is a discontinuity between the visual art creator and the visual art perceiver in such static works. Still, since there is a temporal component in experiencing visual art, visual artists often consciously use rhythm, for example, by regularly repeating elements of art to create the sense of movement (Delahunt 2014).

The discontinuity of rhythm between the visual artist and the viewer becomes something of a non-issue once visual art itself starts moving. Moving pictures have been around since the 1830s (Encyclopedia Britannica 2016). The ability to move static art images in time certainly unleashed a new era in art that further muddied the fine line between dream reality and waking reality. Indeed, legend has it that the addition of the time component to static images apparently caused a riot at a cinema in Paris in 1895 when the short movie Arrival at a Train Station premiered. Space puts us in the world, but time makes it real. The frightened audience members purportedly thought the train was going to come crashing right through the screen, and ran from their seats in terror (Gunning 2002). The advent of the talkies in The Jazz Singer in 1927 completed the illusion, providing filmmakers with a startling ability to transport audience members to strange new worlds while simultaneously controlling their perception of time.

The advent of the film editor suddenly brought the concept of music firmly into the visual realm. Walter Murch, one of the most respected and admired film editors in the history of cinema, compared the development of audible music with the potential for further development of visual music. Murch considered the cinema technique of his day to be roughly where Western music was before the advent of written musical notation. He credited the advent of musical notation to facilitating the tremendous advances in music before the eleventh century, when music was strictly an oral tradition. Murch wondered whether there would ever be such a thing as “cinematic notation” that would allow and instigate the sort of sophistication in visual music to develop that did in audible music (Murch 2002, 50–51).

That transformation may have taken place without the benefit of a visual music notation system with the advent of music videos on stations such as MTV, Music Television. MTV launched on August 1, 1981, in New York City with the Buggles’s prophetic hit, “Video Killed the Radio Star” (CNN.com 2006). Almost instantaneously, MTV popularized visual editing to the beat, bypassing the need for Murch’s cinematic notation by directly conforming the visual music to the soundtrack. The musicality of editing in music videos had a profound effect on everything else in cinema, especially advertising. It dramatically advanced our ability to perceive visual music, in which the content of the actual images often becomes secondary to the hypnotic editing that produces real musical sensations of tempo, rhythm and dynamics.

Closely correlated with the visual music of MTV editing was the rise of the ability to control lighting systems that could also synchronize with a musical beat. Throughout its early life, theatre lighting design focused predominantly on revealing space, although as we noted in Chapter 1, visionary designers such as Tharon Musser were keenly aware early on of the tremendous potential for light to revel in time. But it was the advent of concert lighting in the 1960s in such venues as Bill Graham’s Fillmore Theatre shows in San Francisco, Bill McManus’s designs at the Electric Factory in Philadelphia, and the Joshua Light Show at the Fillmore East in New York that really began to fully explore light as music; all found a way to transform audible music directly into visual music (Moody 2010, 5–6). Lighting designers who wanted to “play the console to the music” drove the development of more and more sophisticated consoles in the 1980s that were capable of greater synchronization with the musical beat (Moody 2010, 112–113). Sophisticated lighting as visual music emerged as a staple of concerts at the end of the twentieth century and led directly to the emergence of another major market for video music, concert projections. Today the visual music involved in just about any major concert rivals that of the audible music itself in complexity and sophistication, especially in highly specialized forms such as electronic dance music, or EDM.

MTV and concert lighting certainly had a pronounced impact on me. After spending many years wondering exactly how to infuse both audible and visual music into legitimate theatre, I started undertaking experiments in the early 1990s, starting with developing my first punk rock musical, Awakening. Awakening started a lifelong exploration into what I call “the gray area between concert and stage, music and play.” In our 2000 production of The Creature, I specifically explored treating each scene like an MTV music video, disrupting the traditional dramatic continuity in favor of a more musical experience. In 2011’s Ad Infinitum,3 we finally abandoned the theatrical convention of a seated audience, which sacrificed a more contemplative seated experience in favor of the extraordinary stimulation of a standing audience encouraged to move with the music. We took the concept one step further in 2015’s Choices, in which we abandoned the premise of a theatre altogether, in favor of setting our story in an EDM club in a style we called thEDMatre. Each successive experience led me to a greater understanding of the immense power of music to take control of the human body, typically unconsciously, without an audience’s awareness. In short, my experiments in this “gray area” have convinced me more and more of the importance of dance in theatre, not just dance on the part of the performers, but as an experience in which the audience also participates.

This idea that music involves physical movement just as much as it does sound is not some new discovery that I’ve just made, however. Ethnomusicologist John Blacking pointed out that music appears to have involved movement for the greater part of human history (1995, 241). Daniel Levitin amplifies that idea, arguing that “One striking find is that in every society of which we’re aware, music and dance are inseparable” (2007, 247). Every society! Later in this book we will examine the biological and neurological underpinnings of the essential connection between music and dance, music and physical movement. But for now, we should simply appreciate that the phenomenon we are attempting to define in this chapter, music, is one that cannot be limited simply to organized sound that we hear. Music is a much more deeply ingrained element of the human experience, one that we may experience with our ears or our eyes, or neither, as we may summon it up from deep within ourselves.

The Elements of Design

Thus far, we have widened our definition of music to include any sound we can possibly imagine, and then widened that to include not only sounds, but visual stimuli as well. We’ve also narrowed, first insisting that our sound and visuals need to be organized, and not just randomly occurring, as art, not for other purposes. We are looking for stimuli that unfold in time, and specifically do not reference to anything in our waking world like language and many visual images do. Lastly, we need to consider the constituent components of music, its elements that help us determine the answer to that age-old question my parents were so fond of asking: “You call that music?”

We started this book by observing that two of the only ways we have of perceiving our external world were through mechanical and electromagnetic waves. We followed the evolution of mammals to witness the development of ears to perceive mechanical waves and eyes to perceive electromagnetic waves. We argued that the ears are really good at perceiving time because of the nature of mechanical waves, and that the eyes are really good at perceiving space because of the nature of electromagnetic waves, although both eyes and ears were quite capable of perceiving that at which the other sense primarily excelled. We then discovered that the mammalian brain took an interesting twist in evolution when it developed not just the ability to perceive sight and sound, space and time, but to generate its own version of reality in a phenomenon we call dreams, and that the brain does this so well that, while under the influence of wakefulness or dreams, we are hard-pressed to remember that the other world even exists. We then went looking for a way to manipulate our brains in these two states, waking and dreaming, and all the states in between, one of which we call theatre. We discovered a great potential candidate in music. But the simple reality remains that the only way we can use music to control perception is by manipulating some form of mass in time and space. More importantly, we need to control our perception of mass, which comes to us in the form of energy either generated directly by the mass, or reflected off the mass. In other words, we should look for the elements of music in the energy characteristics we observe or create and in how they function in our perception of time and space.

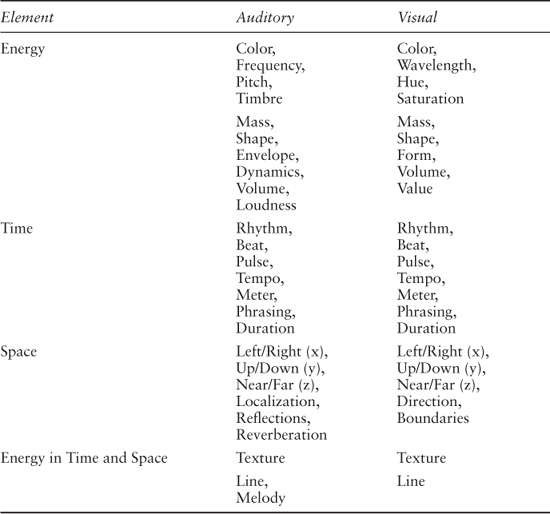

Let’s also not forget that this perspective traces back to my dubious beginnings teaching the sound part of a visual design class. But at the end of the day, it all turned out great, because we now discover in seeking our definition of music that the terms we need to use to describe the elements of music must readily apply to both visual and sonic stimuli!5 In our “formal analysis” of visual design in the class, we considered five components of a visual art object: color, mass (shape and form), texture, line and space (The J. Paul Getty Museum 2011). Van Phillips, who originated the class, had the keen intuition to add rhythm to these five. I then uncovered the auditory correlates of these visual elements, and I’ve been exploring them with my students for almost 40 years now. I’ve changed my approach a bit over the many years since that very first class, but only because we use words to describe things, and words are at best imprecise pointers at what theatre theoretician Eli Rozik calls “real doings.” The elements themselves, thankfully, haven’t changed much, even though others will call them by different names, describe them differently, and organize them in different ways.

Energy Characteristics

When we refer to “energy characteristics,” we refer to either the wave energy that a mass generates, or the energy that is reflected off a mass. One way that the eyes and ears perceive these waves is color. Color is relatively easy to compare, since we refer to our perception of frequency by both the eyes and ears as color. In visual art, we tend to consider the hue (the dominant wavelength), and saturation or chroma (brilliance or intensity of a color, how pure the color is or how much it is mixed with other colors). In sonic art, we describe color in terms of pitch (the dominant frequency) and timbre (the combination of frequencies peculiar to a sound, similar to saturation).

In our original scenography class, we used the term mass, but that term has recently become standardized to shape, which is how we perceive objects in two dimensions, and form, which is how we perceive objects in three dimensions. Nevertheless, for simplicity’s sake, we’ll tend to continue to use the term “mass” in this book when we generically mean both shape and form in either the auditory or visual domain. Both visual and auditory objects have “shapes,” although in sound we refer to the shape of a sound in terms of how it unfolds in time: its envelope. Envelope includes our perception of how a sound starts (its attack), how it initially decays (decay), its characteristics if the sound persists (sustain) and the way the sound ends (release). Together these are known as a sound’s “ADSR” (attack, decay, sustain and release). Both visually and audibly, shape outlines the external boundaries of an object: the former in space, the latter in time.

The third dimension introduced by form also reveals the “volume” of a visual shape. Of course, we use exactly the same term, “volume,” in sound, referring to the apparent loudness of a particular sound source. The greater the volume, the bigger the visual object or sound. One also finds a correlate in the visual design term value, in which the lightness or darkness of an object can be compared to the loudness of a sound, with silence correlating to absolute darkness. In both cases, volume and value, we are considering the apparent mass and size of an energy object, and it is this correlation that helps us sort out big sounds and big visual objects from small ones. Volume simply refers to the size of the sound or visual object itself, while value refers to the intensity of the reflection off the object. Since sound is a mechanical wave originated by the sound object, both terms sort of coalesce into the single term we use to describe this property, loudness, or its correlate when we manipulate loudness in time, dynamics.

Temporal Characteristics

In both visual and audible art, we use the term rhythm to describe how we organize art objects in time. Rhythm curiously uses a similar vocabulary in both visual and sound, particularly dance. Its primary components are beat, pulse, the part we tap our foot to, tempo, or the speed of flow of beats, meter, or how we organize beats in recurring ways, and phrasing, the unique patterns we create with individual objects, and how we group them. Finally, we also characterize sound and movement by how long it lasts, its duration. We’ll spend quite a bit more time talking about these most precious elements of music in the next chapters.

Spatial Characteristics

Space describes the area that encloses the visual or sound object, and includes the visual or sound object itself. Negative space is the area outside the object, and positive space is the space occupied by the object itself. Visual space has two main qualities, direction (left/right or x, up/down or y, front/back, or z) and boundaries. We audibly perceive direction through localization, our ability to evaluate the direction of a sound object through temporal analysis. We audibly perceive boundaries as reflections and reverberations, again temporal characteristics our brain processes and analyzes.

Complex Elements that Combine Energy in Time and Space

Texture is an interesting element in that it has slightly different meanings depending on whether you consider it in its visual or auditory sense. This may stem from the simple fact that the word itself derives from the tactile sensation we get when we actually touch and feel an object. Technically, Webster’s defines “texture” as something composed of closely interwoven elements, and that is precisely what our understanding of the use of the word in sound and visual art have in common (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary 2015). In visual art, texture can be implied in two dimensions by use of color, line, and shading of a color’s value. In music, texture is also created by combining colors (timbres) and melodic lines in various amounts (analogous to shading). The main difference between how one typically considers visual texture and auditory texture, then, is that visual texture typically applies to a single visual object, or a part of a visual object (e.g., the weave of a fabric), while auditory texture often describes how multiple auditory objects work together in a composition (e.g., the orchestration of elements).

The Importance of These Elements of Music

I’ve discovered both in actual practice and in hosting multiple directors and visual designers in my sound classes over many years, that artists appreciate having a common vocabulary in which to engage in meaningful conversation about developing the music for a play—both audible and visual. Learning to understand the nuance of these design elements when used in either visual or auditory composition helps create a more effective way to talk about the music of a play without inhibiting the discussion about the meaning or intellectual communication of the play. It creates a bridge between the world of the sound designer/composer, who primarily creates non-referential elements of the theatre experience, and the visual artists, who often find themselves emphasizing referential elements of the theatre experience, especially considering the propensity of the American theatre toward realism. More than anything, it helps a director more effectively articulate what they are imagining. As one director put it:

This course has deeply enhanced my capacity for examining and articulating the importance of musicality in my directing work. I have long known it was a priority, but I didn’t have the vocabulary to address it with actors or designers…. I no longer feel shy or weird about expressing my intuitions about sound and musicality because I now have knowledge that validates them.

(Anonymous 2015)

In proposing a definition of the word music for this book, understand that we are proposing a practical, pragmatic approach to the creation of music in theatre. It would be pointless for us to persevere through this entire book and arrive at a meaningful aesthetic regarding its role in theatre, only to find that it has no practical use in our artistic endeavors. With that in mind, and with a great amount of cautious enthusiasm, let’s finally move on to proposing our definition of music.

A Proposed Definition of Music

We have established five criteria for defining music as we intend to use the term in this book. First, we must understand music to be a temporal endeavor; music is all about the organization of its elements in time. Second, we acknowledge that music is one of the forms of art. Third, we must carefully separate the referential qualities of words and images used in communicating ideas from the non-referential qualities of music used in creating emotion in an audience and in manipulating perception of time and space. Fourth, we must embrace that music is an endeavor in both auditory and visual art. Fifth, we identify that the elements we use to create music are energy characteristics such as color and mass (which includes elements such as envelope and shape, form and dynamics, volume, loudness, and value), that we manipulate in time and space creating lines and textures.

For the purposes of this book, then, when I use the term “music,” I will mean:

A completely non-referential art form, separate from the referential communication of language and images, that emphasizes the manipulation of time over space through the organization and manipulation of the elements of energy in time and space.

Examples include instrumental music, the speech melody and prosodics of spoken language in poetry, the melody of song, and aspects of the temporal elements of visual art forms such as dance, film and theatre.

Ten Questions

- If theatre is “collective dreaming,” which part of that experience will we focus on in this book?

- What are the two main differences between Varèse’s definition of music and Rodriguez’s? Why are they important?

- What is the difference between the verbs “design” and “compose”?

- What distinction does Cross’s definition of music make that Rodriguez’s and Varèse’s definitions do not make? Why is this important?

- What are two advantages that audible music has over static visual music, for example, the music associated with a painting?

- What are two possible ways suggested by Walter Murch and the advent of music videos respectively that suggest the possibility of a transformation taking place in visual music and lighting?

- What is arguably the most obvious example of a visual art form that is predominantly musical in nature? What physical characteristic of music ties audible music to visual music in this art form?

- List six elements of music as they correlate to both auditory and visual music, and any associated names with the primary element.

- What are three benefits to developing a common language to discuss the music of a play that helps directors and designers communicate?

- What are five very important things to remember any time we use the term “music” in this book?

Things to Share

- Let’s get a feel for the power of referential sound. Go out with your audio recorder, and record a one-minute sound story—60 seconds, please, no more, no less! The catch is that you cannot use any words! What do we mean by story? Well a story should have a beginning, middle and end, as Aristotle pointed out. Keep the story simple, but definitely concentrate on communicating the story to your target audience, our class. We will play your story back for the class, and the rules of the game are that you cannot speak while we are listening or discussing your story. As a class, we’ll attempt to tell you your story, as specifically as possible, just like if it contained other referential language such as words or visual images. The more precisely you can communicate the facts of your story, the more successful we’ll consider your sound story to be!

- Now that you have a pretty good understanding of the element of color, it’s time to explore its ability to stir emotions in your audience. Go out and find five colors, one for each of the following emotions: love, anger, fear, joy, sadness. Look for short sounds, 2–3 seconds long, whose pitch (or lack thereof) and timbre most incite one of these emotions in you. Most important: since we want to explore music, and not referential sounds, please work very hard to avoid any sounds with a referential communication, for example, kissing sounds to communicate love, baby laughing to communicate joy, a man sobbing to communicate sadness and so forth. Find sounds that the audience will not associate with “real doings.”

We will play your five sounds back for the class, and the class will have to suggest which colors most incited which emotions in them. We’ll poll the class to see which sounds they associated with each emotion, and then we’ll ask you for the order you intended. We’ll then tabulate the percentage of emotions you were able to correctly incite in each audience member, and discuss the results.

Notes

1And, of course, we can’t even argue that well, as we all perceive the play from a different physical position, and that implies both a different spatial and temporal stimulus.

2In case you’re wondering, we’ll be building a definition somewhat like Merriam-Webster’s 1a: “the science or art of ordering tones or sounds in succession, in combination, and in temporal relationships to produce a composition having unity and continuity.”

3Definitions for “design,” “compose,” and “composition”:

design: v

- vti to work out or create the form or structure of something

- vti to plan and make something in a skillful or artistic way

- vt to intend something for a particular purpose

- vt to contrive, devise, or plan something

n.

- the way in which something is planned and made

- a drawing or other graphical representation of something that shows how it is to be made

- a pattern or shape, sometimes repeated, used for decoration

- the process and techniques of designing things

- a plan or scheme for something

- something that is planned or intended

compose: v

- vt to make something by combining together

- vt to put things together to form a whole

- vt to arrange things in order to achieve an effect

- vti to create something, especially a piece of music or writing

- vt to make somebody become calm

- vt to settle a quarrel or dispute (archaic)

- vti to set type in preparation for printing

composition: n

- the way in which something is made, especially in terms of its different parts

- the way in which the parts of something are arranged, especially the elements in a visual image

- the act or process of combining things to form a whole, or of creating something such as a piece of music or writing

- something created as a work of art, especially a piece of music

- a short piece of writing, especially a school exercise

- a thing created by combining separate parts

- a settlement whereby creditors agree to accept partial payment of debts by a bankrupt party, typically in return for a consideration such as immediate payment of a lesser amount

- the formation of compound words from separate words

- the setting of type in preparation for printing

Encarta® World English Dictionary © 1999 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. Developed for Microsoft by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

4Word/images simply refers to the fact that both words and images can and typically do have referents in the real world. The word car and an image of a car both “refer” to a car in the real world. A flute playing C sharp has little reference in the real world.

5We’ll save smell, taste and touch for another lifetime, although it is worth pointing out that babies in the first six months of their lives don’t differentiate between the senses. According to Levitin, “Babies may see number five as red, taste cheddar cheeses in D-flat, and smell roses in triangles” (2007, 128). A similar condition called synesthesia exists in adults, in which one sensory organ (e.g., sight) perceives stimulus from another organ (e.g., sound).

Bibliography

Anonymous. 2015. THTR 363 Course Evaluations West Lafayette, IN, December 10.

Aristotle. 350 bce “Poetics.” The Internet Classics Archive. Accessed July 10, 2009. http://classics.mit.edu//Aristotle/poetics.html.

Berlioz, H. 2002. “Berlioz Music Scores: Texts and Documents, Symphonie Fantastique.” August 2. Accessed February 23, 2016. www.hberlioz.com/Scores/fantas.htm.

Blacking, J. 1995. Music, Culture and Experience. London: University of Chicago Press.

CNN.com. 2006. “MTV Won’t Say How Old It Is (But It’s 25).” August 1. Accessed February 24, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20060811230032/www.cnn.com/2006/SHOWBIZ/Music/08/01/mtv.at.25.ap/index.html.

Cross, I. 2003. “Music, cognition, culture, and evolution.” In The Cognitive Neuroscience of Music, edited by I. Peretz and Robert J. Zatorre. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Delahunt, M. 2014. “ArtLex on Rhythm.” March 14. Accessed February 24, 2016. www.artlex.com/ArtLex/r/rhythm.html.

Dowling, W.J. 2005. “Chapter fifteen: Perception of music.” In Handbook of Sensation and Perception, edited by E.B. Goldstein, 470–494. Oxford: Blackwell.

Encyclopedia Britannica. 2016. “History of the Motion Picture.” January 15. Accessed February 23, 2016. www.britannica.com/art/history-of-the-motion-picture.

Gunning, T. 2002. “Early Cinema and the Avant-Garde.” March 8–13. Accessed February 23, 2016. www.sixpackfilm.com/archive/veranstaltung/festivals/earlycinema/symposion/symposion_gunning.html.

The J. Paul Getty Museum. 2011. “Elements of Art.” Accessed February 26, 2016. www.getty.edu/education/teachers/building_lessons/formal_analysis.html.

Levitin, D.J. 2007. This Is Your Brain On Music. New York: Penguin Group/Plume.

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2015. “Scenography.” Accessed February 2, 2016. www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scenography.

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2017. “Aesthetic.” Accessed October 13, 2017. www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aesthetic#h2.

Moody, D.J. 2010. Concert Lighting Techniques, Art and Business. 3rd Edition. Burlington, MA: Focal Press.

Murch, W. 2002. The Conversations. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

Plato. 360 bce. “Republic.” The Internet Classics Archive. Accessed August 4, 2009. http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.html.

Rodriguez, D.R. 2016. “Music and Human Experience.” February 24. http://dox.utdallas.edu/syl17048.

Sacks, O. 2009. The Daily Show (J. Stewart, Interviewer) Comedy Central, June 29.

Stravinsky, I. 1936. Igor Stravinsky an Autobiography. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Svich, C. 2013. The Breath of Theatre. Raleigh, NC: lulu.com.

Thaut, M.H. 2005. Rhythm, Music, and the Brain. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Thomas, R.K. 1980. “A Beginning Course in Theatrical Sound Design.” West Lafayette, IN: Unpublished Master’s Thesis.

Varèse, E., and Wen-Chung, C. 1966. “The Liberation of Sound.” Perspective of New Music 5 (1): 11–19.