Chapter 12

Conclusion: Evolution and Greek Theatre

Introduction: A Case Study

In the last chapter, we saw the emergence of the first four great civilizations of the world, Mesopotamia, Egypt, India and China. Gradually, as human cognition develops, the culture of a civilization took over and it becomes harder and harder to determine when evolution was at work, when advances in culture led, or when both interacted as predicted by the various forms of Lamarckism. But here we are, at a point where we haven’t experienced significant biological evolution for a couple of hundred thousand years, biologically 99.9% the same as our Homo sapiens sapiens ancestors. We’ve reached the end of our evolutionary journey in this book. But rather than conclude by merely telling you what I told you (as the old saying goes), let’s conclude by exploring how all of these evolutionary adaptations may have manifested in a theatre that more closely resembles ours. And what better theatre to examine, than the one that is generally considered to be the first autonomous theatre, the theatre of ancient Greece (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 7). While only displaced 2,500 years or so from our culture, Greek culture provides us with the oldest substantial record of a theatre aesthetic. If the topics we’ve discussed throughout this book have any merit at all, we should find evidence of them in the development of Greek theatre, right? Well, I would be foolish to pick this approach if I wasn’t sure we could!

Let’s not forget that we started this book by remembering that we follow a very Greek definition and interpretation of the word aesthetic: our perception of the world around us through our senses. We accept the evidence presented in this book for what it is, understanding that much of it is, and will remain, controversial. But we expect every artist in every culture to apply it consciously or subconsciously according to their own unique aesthetic, according to how they perceive the world. That not only goes for you and me, but, in this chapter, provides us with an opportunity to examine the various aesthetics of ancient Greek music and theatre artists in the context of their evolutionary underpinnings.

We begin by reviewing the main thesis of this book for which we will be searching for evidence about evolutionary influences in the development of Greek music and theatre. Our thesis, of course, is that theatre is a type of music. It is not words written in a book. It is an experience that has more in common with dreaming than words on a page. It seems possible that separating music from theatre by writing words on a page may even undermine the theatre experience. We traced this thesis through a series of simple formulas that served as major sections of this book:

Music = Time Manipulated

Song = Music + Idea

Theatre = Song + Mimesis

We should find evidence of these formulas at work in the development of Greek theatre that we found in astrophysics, anthropology, biology, neuroscience, and all of the other disciplines we’ve explored throughout this book.

Several themes have emerged as we have explored this thesis. We have learned that our perception of time itself is subjective, and the unique way we experience time has a lot to do with the unique way that music moves from composer through mediated performance and into each audience member. Music affects us at the subconscious level through various types of entrainment and other processes. It arouses our interests and interacts with our memories. All of these processes combine to fundamentally, and often, subconsciously manipulate our emotional states. They lead us into altered states of consciousness that have their basis in dreaming, the shaman’s trances, and primitive ritual. They are perfectly suited to carrying ideas into the conscious and subconscious minds of audience members. Music as a Chariot.

The Origins of Greek Music: Music = Time Manipulated

We start our journey by observing that to the Greek mind, music was a gift of the gods. This should not surprise us. Throughout our journey, music and sound always connected deeply to the cosmology of our Homo ancestors. As far as the Greeks were concerned, Zeus, the king of the gods on Mount Olympus, and son of Kronos, god of time, slept with his aunt Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, for nine nights. The result of that brief affair was the birth of nine Muses (Hesiod 1983, 25–26).

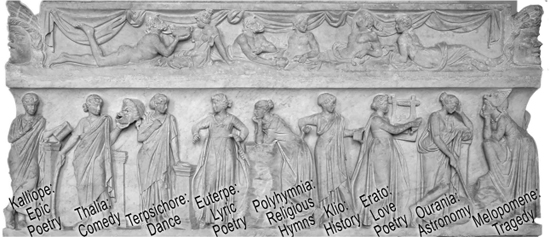

Think about that for a second. The king of the gods was the son of the god of time! And he hooked up with the goddess of memory. This would be the same memory that we quoted Daniel Levitin in Chapter 10, saying that without it, music could not exist! Zeus and Mnemosyne’s progeny were the nine Muses. Each Muse, a goddess in her own right, inspired a different temporal art: Klio, the Muse of history, things that take a long time; Thalia, the Muse of comedy; Melpomene, the Muse of tragedy; Terpsichore, the Muse of dance; Erato, the Muse of love poetry; Polyhymnia, the Muse of choral poetry and religious hymns; Kalliope, the Muse of epic poetry. Then there’s Euterpe, the Muse of music, the temporal art we most often associate with the audible form of music produced by musical instruments. The Greeks often depicted her holding an aulos (a type of Greek flute) or a lyre (a stringed instrument). Finally, there’s Ourania, the Muse of astronomy.1 The Muse of astronomy? We’ll come back to that later in this chapter, but rest assured that the Greeks perceived a very fundamental and temporal relationship between music and astronomy. Most importantly, we see that the Greeks developed a very fundamental understanding of the unique relationship between time, certain arts, and hearing very early on, just as we explored in Chapter 2.

Figure 12.1 A sarcophagus from the first half of the second century ce shows the nine Muses.

Credit: Photo by Jastrow, original located in the Louvre Museum, in Paris, France.

And so, in the very earliest manifestations of Greek culture upon which much of western civilization would be built, we see a fundamental recognition that Music = Time Manipulated.

But there is one more element of the mythology of the Muses that we must not overlook. The Muses did not simply govern the temporal arts, they inspired them. In Greek cosmology, we see a rather sophisticated understanding of how music transmits from one entity into another. It doesn’t use symbols or signs. It doesn’t reference anything. It simply connects, like entrainment, startle, habituation and other physiological and neurological processes we have investigated. The Muses helped the Greeks explain the unique way that music incites responses in listeners— the same phenomena we have explored throughout this book, especially in Chapter 9, where we examined the role of sound in altering the conscious states of the shaman and the shaman’s subjects.

Much later, Plato would describe the essence of this process brilliantly in his Ion:

The gift which you possess of speaking excellently … is not an art, but … an inspiration. There is a divinity moving you, like that contained in the stone which Euripides calls a magnet, but which is commonly known as the stone of Heraclea. This stone not only attracts iron rings, but also imparts to them a similar power of attracting other rings; and sometimes you may see a number of pieces of iron and rings suspended from one another so as to form quite a long chain: and all of them derive their power of suspension from the original stone. In like manner, the Muse first of all inspires men herself; and from these inspired persons a chain of other persons is suspended, who take the inspiration.

(Vol. I, p. 501)

The mythological view of the Muses identifies several very important concepts we have explored in this book:

- It identifies the predominantly temporal arts and organizes them together.

- It predicts the close relationship between memory and music (the Muses were the progeny of Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory).

- It describes how the process of musical inspiration works (from composer/playwright, through performer to listener).

The Development of Greek Song: Song = Music + Idea

The earliest agricultural settlements in Greece occurred about 7000–5000 bce in Sesklo, Dimini and Crete (Thomas 2014, 10).

One group, the Minoans, named after the legendary king Minos settled on Crete about 3000 bce. In about 1600 bce, a gigantic volcanic eruption on the nearby island of Thera disrupted the Minoan civilization (Thomas 2014, 21–22). This made them pretty much sitting ducks, easily overtaken by a much more aggressive and warlike group from Mycenae on mainland Greece. The Mycenaeans appeared in Greece around 2000 bce, and are best known for their siege on the city of Troy in retaliation for the Trojan kidnapping of Helen, the wife of the Spartan king, Menelaus. The whole escapade resulted in the brilliant deception known as the “Trojan Horse,” in which the Greek army hid a number of men in a large wooden horse, and left it as a gift for the Trojan army after an unsuccessful siege. The men, once inside, opened the gates so the rest of the Greek army entered and destroyed the city of Troy (Kanopy Streaming, 5:42).

Out of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures comes the first evidence we have for a distinctly Greek language that descended from the Proto-Indo-European language we first met in Chapter 11. Written language appears on thousands of tablets known as the Linear A (Minoan) and Linear B (Mycenaean, derived, from the Minoan) writing systems (Thomas 2014, 21; Mallory 2006, 28). The Linear B tablets give us a record of Greek mythology that dates back to the Bronze Age. But these tablets rarely provided more than simple records of how many sheep produced wool, or the number of chariots—and spare wheels, of course! Spoken language, on the other hand, diverged geographically and developed separate dialects, the unique music of the spoken word.

Figure 12.3 Map of ancient Greece shows earliest settlements, Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations.

Credit: Best-Backgrounds/Shutterstock.com. Adapted by Richard K. Thomas.

Oral traditions developed specifically to each ethnic group and geographical area. And when these early Greeks mused about the gods, they “sang” in a way that closely resembled the dialects, a practice that the classical scholar M.L. West contended may have originated in the Proto-Indo-European language. West also contended that the Greeks may have inherited a very basic method of music notation from the Indo-Europeans in which marks are placed above the text that indicated one of three possible pitches that might be sung—although no extant examples exist (West 1981, 115).

Around 1200 bce, a variety of disputed causes ranging from invasion by a people from the north known as the Dorians to environmental catastrophe, thrust Greece into a period of famine and hardship known as the Dark Age.

The Mycenaean Linear B writing disappeared and only Athens survived. Athens had a fortress called the Acropolis that was fortified with walls and its own water supply (Kanopy Streaming, 3:19; Thomas 2014, 31–32). Curiously, Greece descended into its Dark Age just as the next archaeological period, the Iron Age, began in other parts of the world. As you can imagine, during the Iron Age, humans learned the superior qualities of iron over bronze.

Figure 12.4 Derivation of Greek languages and dialects from Proto-Indo-European.

Credit: Map Adapted by Richard K. Thomas from original by Fut.Perf. Based on source map by Roger D. Woodard. 2008. “Greek Dialects.” In The Ancient Languages of Europe, 51, edited by Roger D. Woodard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Three distinct tribes emerged: the Mycenaeans, who would eventually become associated with the Ionian dialect and Athens; the Dorians of Northwest Greece, who eventually became associated with Sparta among many other areas; and the Aeolians of the northeastern territory that become known as Thessaly.

Of course, if you asked the Greeks of the period, Zeus destroyed the men of the Bronze Age, and allowed Prometheus’s wife, Pyrrah, and son, Deucalon, to repopulate the planet by throwing stones over their heads, which turned into men and women (Appolodorus 1921, I-7.1–3).

In the absence of a written record of language in the Greek Dark Age, the oral tradition continued. Myths and language morphed into many different stories and dialects in many different locations. Politics and rivalries deeply divided the different tribes, especially the cities of ancient Greece (Encyclopedia Britannica 2016). In these early ethnic groups, music and language were so closely associated with one another that particular speech melodies (i.e., pitches and rhythms) would be named after their home region, for example, Ionian, Dorian or Aeolian. Although scholars have long debated the issue, it appears that singing also became stylized according to the dialect of the particular race or geographical area. The music of language would become a critically important aspect of ethnic culture, just as it often is today.

By the end of the Greek Dark Age, about 800 bce, the singing and recitation of poetry were often accompanied by the four-string lyre (West 1981, 116). The four notes that each of the strings provided limited the notes the performer could sing. So, how one tuned the lyre had a lot to do with the possible melodies. The meter of the poem dictated the rhythm and the pulse. We must imagine that the story itself dictated the tempo. The lowest string and the highest string were typically tuned a fourth apart, providing an opportunity for consonance. The inner notes depended on the particular type of scale, providing different opportunities for more or less consonance or dissonance with each scale used.

Playing the lyre also became stylized according to the dialect of the particular race or geographical area, because, as West suggested: “instrumental accompaniment went in unison with the voice” (West 1981, 115). In addition to the Ionian (Athens), Dorian (Sparta) and Aeolian (Thessaly) dialects, other dialects become known to the Greeks; the Lydian (western Anatolia, or Turkey), and Phrygian (west-central Anatolia, see Figure 12.4), sharing its western border with Lydia. Without a written language, the burden of passing down ideas from one generation to another fell to the oral tradition, requiring a close association between language (idea) and music (emotion). As we discovered in Chapter 10, using music to carry and preserve ideas was much more than just a pleasantry. Tempo, meter and rhythm provided a vital method to chunk ideas into more memorable forms that could be more robustly transmitted from one generation to another.

Two voices emerged in the late eighth/early seventh century bce that would forever alter the worlds of music and theatre: Hesiod and Homer. It was Hesiod who first told us about the origins of the Muses. Scholars largely credit Hesiod with writing the poems that set down the stories of the Greek gods that proliferated during Greece’s Dark Age. The Greek poet Homer set his stories to verse in two works: the Iliad, which describes the end of the Trojan War and the legend surrounding the famous siege, and the Odyssey, which covers Odysseus’s (Ulysses’s) long journey home after the Trojan War.

Both Hesiod and Homer are most likely to have composed and passed down their poems orally, even though the Greeks had commandeered the Phoenician alphabet as early as 800 bce. This was a period of transition from the oral tradition to fully written out works in ancient Greece, although, it would seem that both Homer and Hesiod developed their works during a period of the oral tradition and only would have written them out later in life (Hesiod 2004, xii–xiv). Originally, artists called “rhapsodes” created their vocal performances on the four-string lyre, but West still considers their singing to be a “stylized form of speech, the rise and fall of the voice being governed by the melodic accent of the words” (West 1981, 115). Eventually, the Greek alphabet would improve on the Phoenician alphabet by adding vowels—α (a), ε (e), ι (i), ο (o), υ (u)—that allowed a more faithful representation of actual speech (Encyclopedia Britannica 2016).

The classical Greek musical system developed by attempting to match the speech melody as closely as possible. It’s not hard to imagine, then, that they would develop melodic systems based on the various dialects, such as Dorian or Phrygian. These melodic systems, called modes, were scales constructed from varying combinations of intervals between successive notes. Melodies were based on the consonant interval of the fourth, in between were notes of varying dissonance that made the scale more closely resemble the dialect stylistically. Notice how the scales developed on the basis of the consonant and dissonant relationships we examined in Chapter 8.

In the seventh century, a seven-string lyre would be introduced—conveniently right when the various musical melodies in the Dorian, Lydian and Phrygian modes spread throughout Greece.

As necessity is the mother of invention, the seven-string lyre possibly arose as a solution to the problem of performing different poems based on the different ethnic dialects. Rather than laboriously retuning between each song, the rhapsode could tune the seven-string lyre to multiple modes at once, and simply change the strings played depending on the needs of the song. Most modern folk singers recognize this problem—but they have precisely engineered tuning pegs, capos and digital electronic tuners to speed up the process! The expansion of the scale from four notes to seven not only solved the technical problems of performing poems written in different “dialects,” but allowed for much greater virtuosity of performance.

The seven-string lyre eventually gave way to the larger, more professional cithara (also spelled kithara—notice the resemblance to the word guitar).

Curiously, a split developed between rhapsodes and citharodes at the same time the words—but not the music—started getting written down. Rhapsodes were more concerned with the faithful transmission of the lyrics; citharodes were more concerned with virtuosic musical improvisation (West 1981, 120–125). In Chapter 7 we discussed how music and language shared some neural networks in their processing of sound, how some parts of the brain used parallel systems that process speech in the left hemisphere and music in the right, and how some areas of the brain process music and language in distinctly different ways. It seems possible, then, that as Greek music developed, the artists became more consciously aware of the possibilities created by a brain that processed music and language differently, and increasingly learned how to make use of the diverging nature of the processing mechanisms of each.

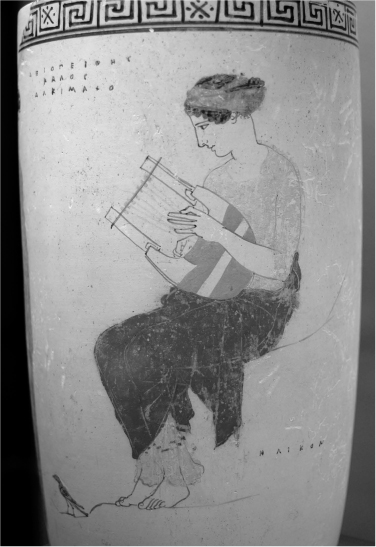

Figure 12.5 Muse playing a seven-stringed lyre, 440–430 bce.

Credit: Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol. Original located in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich, Germany.

Credit: iStock.com/Nastasic.

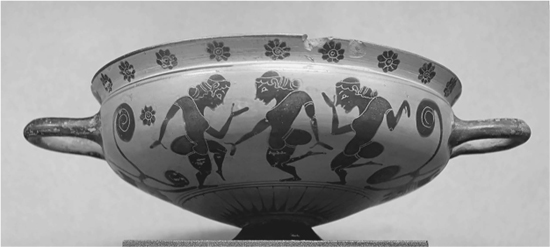

Figure 12.7 Komasts dancing circa 575–565 bce.

Credit: Photo by Jastrow, original located in the Louvre Museum in Paris, France.

Decorative vases started to appear in the middle of the seventh century bce, that depicted scenes of choric rituals.

A couple thousand of these vases have been uncovered, depicting male dancers called komasts, generally in large groups. These vases are important for they depict iconically the world of the Greeks during a time when textural fragments are few and far between. Without exception, the komasts dance, and often their musical accompaniment is shown with them (typically flutes).

The Dorians in Corinth produced most of these vases and exported them to all parts of the Greek world. Significantly, Corinth is also said to have birthed a choral hymn called the dithyramb during this same period, although this is not the whole story. Archilochus, a poet from the island Paros credited with inventing lyric poetry, appears to have sang personal dithyrambs in 640 bce. Archilochus may also have been the first person to use music as “underscoring,” that is, rather than always having the music follow the speech melody, the performer would speak the words with music “below the song” (Mathiesen 1999, 72). But it was Arion, a professional musician on the cithara, who is credited with composing, naming and teaching a public dithyramb in Corinth (Caspo and Miller 2007, 11).

During the course of the sixth century, dithyrambs developed as a processional ritual danced and sung to honor the god Dionysus (Caspo and Miller 2007, 11). Its origins may have included erotic elements and not been very far removed from phallic songs (Pickard-Cambridge 1962, 1–2). Thomas Mathiesen cites several ancient Greek writers who describe the dithyramb in similar ways: the dithyramb was “full of passion,” “tumultuous and appears in a highly ecstatic manner … hurried along by its rhythms,” and its use of “simpler diction … discovered from … merriment in drinking” (Mathiesen 1999, 71–74). It’s hard not to notice the similarities of this to the shaman’s art we have explored in the last few chapters. One way or another, these early audiences were constantly being led into altered states of ecstasy invariably grounded in musical stimuli. Wine was also a major theme depicted on the komast vases, so one can imagine the original qualities of these drunken orgiastic processions. Combined with music, they certainly would form a certain archaic fulfillment of the “drugs, sex and rock n’ roll” neurological entanglement we explored in Chapter 9.

As we shall see, the dithyramb holds a very special place in our story.

Greek language and culture became more homogenized as the Greek ethnic groups increasingly interacted in the sixth century bce. Types of poetry that had originated in various dialects spread orally to other groups and morphed to include linguistic characteristics of other cultures. Epic poetry, particularly Homeric epics, became a highly stylized artificial mixture of dialects. Homeric epics were thought to be based on the Ionic dialect, but in actuality were an artificial dialect based on Ionic but included Aeolian and Mycenaean elements (Encyclopedia Britannica 2016; Mallory 2006, 28). Homeric epic language would, in turn, influence other types of poetry, such as choral lyric. Personal poetry would naturally retain the dialect of its creators, be it Ionic, Lesbian, Boeotian or others. The effect of the telephone game we discussed in Chapter 11 was to blend and combine different ethnic groups over a long oral tradition into a more homogeneous environment.

Dialects from different regions eventually became more associated with different types of literature and music. A good example of such a homogenization of cultures is the dithyramb we met earlier that Arion first performed publicly in Corinth. Corinth is more natively Dorian, but dithyrambs were performed almost exclusively in the Phrygian mode (Phrygia being a central Anatolian dialect). Aristotle tells us that Philoxemus tried to compose a dithyramb in the Doric mode, and simply couldn’t—he had to revert back to the Phrygian mode to get it to sound right (Aristotle 2009c, Book Eight, Part VII)!

The spread of the Greek language and the mixing of ethnic groups in the sixth century led to each mode developing a “characteristic sound”—probably at the expense of faithful imitation of the dialect from which the mode originated. An oft-cited quote argues, however, that “When Lasus (a sixth-century poet) … referred to the Aeolian harmonia, he was probably thinking less of a scale pattern than of a melodic style that had become localized among Greeks who spoke the Aeolic dialect” (Anderson and Mathiesen 2007–2016). But how much we can expect these Greek modes to reflect the actual dialects of a people, morphed over hundreds of years, is open to much speculation and debate.

Eventually, the Greek alphabet spread not only to the Greek races, such as the Dorians, Ionians and Aeoleans, but also to the other nearby races, including the Phrygeans and Lydians. Writing further enabled the referential power of language to become separated from the musical characteristics of spoken words. Eventually, the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, transitioned from an oral tradition to a written tradition as the Greeks further developed their alphabet.2 Music and language parted company, palpably manifested in the separation of prose and poetry. Isobel Henderson describes the consequences of this in the New Oxford History of Music: “The spread of books may even be thought to have pushed music out of education, for the mutual aide-memoire of verse and melody was no longer indispensable when the words were easily available in written copies” (1955, 338). Recall how in Chapter 10 we explored how organizing our memories according to principles of music helped make recalling text easier. Remember FAT DOG EAT PIG? In the absence of a written tradition, the music of language, especially when stylized into the meter and verse of poetry could have been an essential tool in storing Homer and Hesiod in the collective conscious. Written language would have cut the cord on that particular partnership.

This slow separation of music and language may be of greater significance than we initially imagine. Let’s remind ourselves of how we got started all the way back in Chapter 1. We began this book by lamenting the disassociation between sound design and music from theatre, and blamed the phenomenon on the fact that “electronic theatre sound design as we now know it, came to the theatre table pretty late.” That may be true, but let us now consider the separation of music and theatre brought on by the emergence of written language, and the subsequent disassociation of the experience of theatre and what is written in a published play. In such a system, we suspect a problem much more pervasive and undermining: our tendency to treat the written text of a play as the experience of the play itself. Theatre production has become a process of reverse engineering: attempting to find the music of a play by studying the written language of a play. Musicals (and opera!), of course, reversed this trend, and we can plainly see the positive effects this has had on the theatre experience: musicals run on Broadway for years; plays for months. There can be no denying that the essence of the theatre experience rooted in the underlying music has a magnetic attraction that draws modern audiences in substantial and demonstrable ways. Worth keeping in mind as we proceed. We’ll notice a similar phenomenon in Greek theatre.

Later in the sixth century, the various modes more fully morphed into scales bearing the name of their origin, but each having its own characteristic rhythm and pitch structures as we discussed in Chapters 6 and 8. Eventually, each mode became associated with a specific type of character and/or emotion. For example, the Lydian scale seemed to be good at expressing sorrow. The Aeolian, which, as we mentioned before, bore some relationship to Homer’s dialect, had a nice quality that existed between “tense and relaxed.” It was perfectly suited, according to “the outspokenly conservative poet, Pratinas of Phlius … to braggarts in song” (Anderson and Mathiesen 2007–2016). Compare this to Robert Thayer’s components of mood we discussed in Chapter 9 (calm to tense, and tired to energetic). Notice how the Greeks slowly developed a system of melodies and lines, each more suited to creating and experiencing one mood over another.

Over a long period of time that extended well into the fifth century, styles began to become separated from their geographic origin, and began to be associated with particular musical patterns, the prosody of the rhapsodes. Poets eventually emerged that favored a particular musical style without necessarily following the dialect or the language. Sappho (see Figure 12.6) and Alcaeus favored the Aeolean style, Pindar was said to have a Lydian manner. Pindar also composed in both Aeolean and Dorian styles—and apparently sometimes confused them. Pratinas called his music Dorian (Henderson 1955, 382–383).

As the performance of poetry developed and flourished, the particular mood of a poem or song would become associated with an emerging concept, ethos. Ethos is a complex subject with many different meanings but Anderson and Mathieson connect it directly back to music: “When indications of ethos occur in poetry, they almost always concern mood rather than morality.” By the end of the sixth century bce, the strange ability of music to influence mood also became associated with mimesis, and mimesis would thereafter become associated with ethos.

Here we have one of the great paradoxes of the close relationship between music and theatre: for the Greeks, even mimesis had its roots in music. In its original conception, mimesis involved imitating sound, but it meant much more; Plato would later make that clear (Mathiesen 2016). Mimesis had more to do with the power of sound and music to reach the inner recesses of the soul and affect a person’s ethical and moral states, their ethos. Gerald Else ascribed the origin of the term to the expressive primeval power of “mousikē” in music and dance. Else argued that the interpretation of imitation was a later, and inappropriately applied use of the term to such art forms as painting (Else 1958, 73). Like the iron rings that took on the characteristics of Plato’s magnet, the Muses permeate through the composer, then the performer and finally into the listener, inciting particular moods in each along the way. It’s hard to imagine that the genesis of the word mimesis itself, as we use it in our more modern sense, had its origin in music.

Could the moods created by music actually cause specific moral or ethical states to develop? So began a discussion about the relationship of mimesis (the mysterious power of music attached to ideas) to ethos (the manner in which ethics and morality were instilled in virtuous citizens). The Greeks slowly became aware of the special power of Music as a Chariot, when we use music to carry ideas into the hearts of humans. They explored it specifically in their consideration of mimesis and ethos. And it made a lot of them very, very nervous. Consider the “drugs, sex and rock and roll” excesses of the Dionysian festivals, and one can quickly imagine why. That debate still carries on today, and it strikes at the heart of our discussion about the nature of the experience of music. We will return to it later in this chapter as we explore the difference between how Plato viewed the phenomenon, and how Aristotle viewed it.

Music as Math Made Audible: The Greeks Revisit Consonance and Dissonance

One of the earliest Greek scholars to tackle the complex subject of the relationship between music and ethos was the sixth-century Ionian mathematician Pythagoras, and the cult that followed him, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras was born in Syria around 575 bce, and studied in Egypt for 21 years before being captured and taken to Babylon, where he studied music and mathematics for 12 more years, among other disciplines. He then settled in Samos, a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It was there that he founded a cult that promoted theories about the harmony of the spheres that detailed relationships between the harmonious ordering and movement of the planets and harmony in music.

Pythagoras and his cult taught about mathematical relationships between the order of the planets and the order of notes found in music. They thought that the same simple harmonic structures we’ve discovered that govern consonance and dissonance in Chapter 9 appear in the movement of planets in the heavens, in the seasons of the year, in all of the universe. A couple of hundred years later, Aristotle, in his Metaphysics, would describe this worldview:

since, again, they [the Pythagoreans] say that the attributes and ratios of the musical scales were expressible in numbers; since, then, all other things seemed in their whole nature to be modeled after numbers, and numbers seemed to be the first things in the whole of nature, they supposed the elements of numbers to be the elements of all things, and the whole heaven to be a musical scale and a number.

(Aristotle 2009a, Book I, Part 5)

Aristotle claimed that the Pythagoreans believed that the heavenly spheres actually produced sound:

the motion of bodies of that size must produce a noise, since on our earth the motion of bodies far inferior in size and speed of movement has that effect. Also, when the sun and the moon, they say, and all the stars, so great in number and in size are moving with so rapid a motion, how should not produce a sound immensely great? Starting from this argument, and the observation that their speeds, as measured by their distances, are in the same ratios as musical concordances, they assert that the sound given forth by the circular movement of the stars is a harmony.

(Aristotle, 350 bce, Book II, Part 9)

For the record, Aristotle thought that they were a bit off on this one. Still, we should not underestimate the importance of this connection. Remember that we promised to return to the subject of Ourania, the Muse of astronomy? For the Greeks, astronomy was not only a time art, but also more closely connected with music than visual arts and space. Jamie James sums up those relationships: “It is clear that the Pythagoreans did not simply discern congruities among number and music and the cosmos: they identified them. Music was number, and the cosmos was music” (1995, 30–31). Michael Thaut explained the predominant view that “In ancient Greece, music was considered in many ways to be a part of the natural sciences … one could study music to gain insights into important aspects of the physical world” (2005, 28–29).

It is not hard to understand, then, that, given that worldview, the Pythagoreans imagined a very close relationship between the ethos of the modes—in the context of the ability of music to influence moods—and ethical states. Henry Farmer goes on to explain in the New Oxford History of Music:

music, being a cosmic ingredient, possessed qualities and sensibilities which could evoke the like if the appropriate and related kind of music were used. Thus, one species would banish depression, another would assuage grief, a third would check passion, while yet another would dispel fear.

(Farmer 1957, 247)

Anderson and Mathieson suggest that while the origins of the belief in the “magically potent” power of music to affect ethos was born in the Near and Middle East, “the liberating force was Pythagorean theory, whereby musical phenomena were brought under the control of number and of proportionate relationship” (Anderson and Mathiesen 2007–2016).

The influence of Pythagoras on the Greek worldview was pervasive. It reflected an element of society that was somewhat preoccupied with mathematics and science— to the point that it was suspicious of anything that challenged its logic and rigor. As we shall see, the Greeks grew especially suspicious of the mysterious power of music to stir the emotions and moods of its audience and to alter the conscious perception of the individual. These would increasingly be considered real threats to the state. Over a long period of time, music came to be seen as a way to influence morality, one that should be used specifically to carry “good” ideas. As we discussed in our section on implicit memory in Chapter 10, the Greeks understood not just the power of music to carry ideas, but the power of music to create an impression of truth magnified by the mood induced by the music. Music as a Chariot.

The First Autonomous Theatre: Theatre = Song + Mimesis

Pythagoras arrived in Greece in the mid to late sixth century to find a strong performative element that had already emerged out of a long oral tradition thriving in ritual festivals all over Greece. The dithyramb was but one genre of festivals that sprang up and featured competitions of epic poems dedicated to particular deities, first perhaps in Sparta or Delphi, and then spreading to the rest of Greece (Henderson 1955, 379). By this time, dithyrambs had branched out from purely Dionysian rituals to poems that honored other gods and more serious subject matter. Dithyrambs contained a strong narrative component and were accompanied by the aulos (Henderson 1955, 379). Throughout this transition from storytelling and ritual enactment to a completely autonomous theatre, tension existed between referential language, and emotional music. Rozik notes this tension early on suggesting that Lasos may have inaugurated a “predominance of the music over the words against which … Cratinas shortly afterwards protested” (Rozik 2002, 246; A.W. Pickard-Cambridge 1927, 50).

The stage was set for the birth of theatre, and Athens was ground zero. While the Greeks developed their conception of mimesis and ethos, a big party was breaking out in Athens. Two dithyrambs were known to have been performed at the Great Dionysian festival that was established in 534 bce (Mathiesen 1999, 79). Thespis, a singer of dithyrambs, won his first contest in Athens that year (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 11). Eli Rozik notes how this coincides or slightly predates Lasos’ institution of dithyrambic contests in Athens with “some elaboration of the rhythms and the range of notes employed in the music of the dithyramb” (2002, 146). Caspo and Miller also credit Lasos for introducing the circular chorus to the dithyramb that would later serve as the foundation for the Greek theatre chorus (Caspo and Miller 2007, 11). Rozik suggests that dithyrambs and tragedy were most likely very similar at their start and probably existed side by side for some time. Indeed, Mathieson describes dithyrambic performances that were apparently full of dramatic “sound effects” provided by the audience in the form of onomatopoeic neighing horses, or hisses of snakes, and percussion toys such as crotalas or clappers (Mathiesen 1999, 76–77). The differences between dithyrambs and tragedy are most likely not as well divided as the names might suggest. The development of tragedy most likely took place over some time, rather than emerging full-blown one fine day. Rozik describes a significant connection between the two:

As a choral, danced, and sung performance, dithyramb could indeed have been a source of tragic theatre…. The imitation of a serious-sublime action is a property common to both storytelling and drama. This view is congruent with the continuity and supposedly smooth transition from dithyramb to tragedy, since both share the presentation of heroes and their actions in a serious and lofty or, rather, tragic style.

(2002, 150)

Tragedy (which derives from the Greek τραγῳδία, meaning “goat song”) required one more critical invention in order to become theatre, the invention of the actor. Rozik argues that the main difference between dithyrambic choral performances and tragedy was “the introduction of actors, who represent characters by enacting them and their doings” (2002, 150). Thespis is generally credited with introducing the actor to tragedy—a character that speaks directly to the chorus, and thus creates dialogue (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 11). The introduction of an actor who portrayed characters in first person, rather than told their stories in third person as storytellers did, so fundamentally changed the auditory experience that a new art form was born, theatre. Theatre = Song + Mimesis.

With the addition of the actor, the essential tools for achieving the dramatic experience were in place: language, music, and a very specific type of mimesis. Language provided the referential information necessary to imagine the world and all its details, music subconsciously aroused, manipulated time (especially through rhythmic entrainment) and incited emotional responses. The actor anchored the language and music in a tangible, physical organism that bore such a strong resemblance to the character portrayed that audiences no longer perceived themselves in their theatrical surroundings, but began to perceive themselves in the world of the dramatic performance. This experience of course also occurred to a certain extent in storytelling, because both theatre and song have their basis in music.

At the very end of the sixth century bce, the ritual processions of the dithyrambic performers found an important end to their procession in the Theatre of Dionysus of Athens. Prior to this, performances had been held in the central market square (agora) or a public park on the southeast slope of the Acropolis (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 16). But the Theatre Dionysus was a permanent theatre, built around the “dancing space,” the circular orchestra. Theatre now had a home, and it was built around a fundamentally musical type of performance.

In the beginning, these performances were filled with music. The chorus sang as many as half the lines. Much of the remaining dialogue was sung or delivered as recitative, and dance was part of many scenes (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 18). Even at this late date, music and language, united in speech were typically inseparable. The earliest dramatic performances were centered around one unique individual who wrote the play, composed the music and dances, trained the chorus, played the single acting role established by Thespis, and oversaw every aspect of the production. As an actor this uber-creator did not focus on reproducing the attributes of the character so much as they did on inciting emotion. The chorus comprised 50 amateur members of the community. There was no scenery, no lighting, and the vases of the period do not even make convincing arguments for much in the way of costumes (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 18–20). Essentially, there was the actor and the chorus, music and dance, and language, with music clearly a dominant force arousing strong emotions.

In the fifth century bce, music, idea and mimesis flourished in the newly discovered music form, theatre. Theatre continued as an oral tradition throughout much of the fifth century (Henderson 1955, 336). Most of the plays that we now know from Greek theatre—from playwrights such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes—were written in the fifth century bce.

The fifth century bce was also the period of the great philosopher, Socrates, who was not only very suspicious of Greek democracy, but also of any form of writing things down. Unlike Merlin Donald in Chapter 8, Socrates suspected that the offline storage of writing things down could lead to replacing human memory, making human memory weaker, which, in turn would lead to a lack of wisdom (Vol. I, p. 485).

But the handwriting was on the wall. As the fifth century went on, the role of instrumental music started to wane, in favor of the ideas of the play. Aristotle tells us that Aeschylus (525–426 bce) introduced a second actor and then diminished the role of the chorus. Sophocles (495–405 bce) introduced the third actor (about 468 bce, according to Brockett) (2007, 12). Plot took on greater and greater importance and the rhythms of dancing were replaced by the more “natural” rhythms of colloquial speech. “Nature,” as Aristotle would much later say, “herself discovered the appropriate measure” (Aristotle, Poetics (350 bce) 2009, Part IV).

What could have caused such a drastic shift away from a form that had such strong evolutionary ties throughout human and animal history? The obvious answer would seem to be that the more “natural” style of theatre, with its greater emphasis on plot and dialogue, was more popular with its audiences. However, there may have been other forces at work here.

One must remember that a significant part of Greek society was quite suspicious of the power of music to sway human emotion, and felt that the purpose of music was more properly related to its mathematical connection to the cosmos, as the Pythagoreans believed. Henderson describes the interest of Greek theorists “not to analyze the art of music but to expound the independent science of harmonics” (1955, 336). Government was skeptical of the ability of music to affect ethos, and was not anxious to return to the hedonistic ways of satyrs and Dionysian excess. The government needed to co-opt the festivals in order to assure that they improved the moral and ethical disposition of the citizens and inhabitants of Greece.

The government provided the theatre space, prizes, and payments to the actors and possibly dramatists (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 17). An author wishing to present a play had to apply to the archon, the “chief magistrate” of the Greek city-state. It is no wonder that the plays produced would increasingly focus on the psychological and ethical attributes of their personages, a far cry from the ritualistic excesses of the early Dionysian rites (Brockett and Hildy 2007, 12). Only the more ribald satyr plays, about half the length of the tragedies, and only performed after trilogies of tragedies, were allowed to appeal to the baser side of human nature.

Further complicating matters was the problem that the words of the plays were apparently written down, but there did not appear to exist a similar technique for recording music—Greek writers constantly quote literary texts, but not musical ones; figures on vases perform music, but none reference written music (Henderson 1955, 337–338). Music remained a prisoner of the oral tradition, largely improvised, whereas language was stored outside the memory in written form. Cartwright goes even further, suggesting that “scripts regarded as classics, particularly by the three great Tragedians, were even kept by the state as official and unalterable state documents” (Cartwright 2013). I don’t mean to be a conspiracy theorist here, but a government that had developed a deep and abating suspicion of the negative power of unchecked musical expression on an unsuspecting populace, would have a particular interest in supporting and preserving the “good” ideas, and would be just as happy to see music disappear altogether. Or, it was just a matter that no one invented a music notation system that caught on. Regardless, eventually the music of the great plays would inevitably be lost, while the written record of the ideas of the plays would be preserved. In the process, drama was born. Drama is the written down text of the performance. It’s good at recording ideas, very poor at recording music. Theatre is the actual performance, and includes every aspect of the performance, especially the music upon which it is based.

One final important development Mathiesen notes is the “rising importance of the instrumental virtuoso.” As music became further separated from written text, the musicians found a new sense of freedom for self-expression that also would eventually lead to a further parting of ways with the spoken word (Mathiesen 1999, 75). One would think, then, that advancements in writing would have produced a plethora of new dramatic works, each logged meticulously in written form, and recorded and resurrected throughout the ages. Yet, by the time Plato arrived on the scene, the great works that have been passed down to us through the centuries had just about all been written. And Plato was firmly of the mind that the purpose of music—that which we call song and includes its offspring, theatre—should be carefully controlled by the state to ensure it helped ennoble virtuous men.

Plato and His World

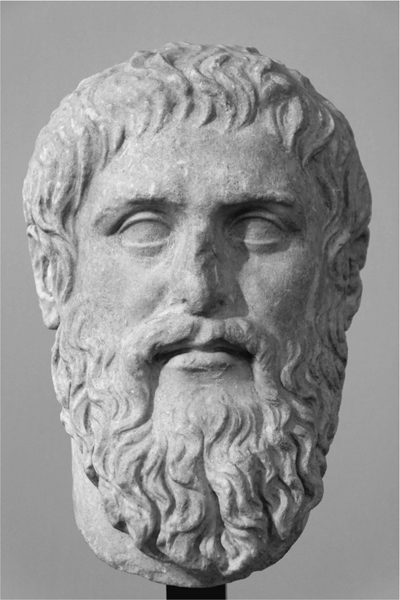

Up until now, we’ve met Plato and Aristotle primarily as historians who happened to be a couple of the best authorities closest in time to early historical events. But in reality, both Plato and Aristotle came much later than most of the events we’ve been describing. Plato was born around 428 bce, fully 100 years after Thespis was said to have introduced the first actor.

Plato’s earliest dialogues didn’t appear until the next century, when he was deeply affected by the trial and execution of his mentor, Socrates in 399 bce (Meinwald 2016). Plato may have known the great playwright Aristophanes; at least that’s what’s implied by including him as a character in Plato’s Symposium. Aristotle was Plato’s student, so he was even further removed from the age of the great classic theatre.

Plato followed the Pythagoreans. The influence of Pythagoras on the Greek worldview was pervasive. It reflected an element of society that was somewhat preoccupied with mathematics and science—to the point that it was suspicious of anything that challenged its logic and rigor. As we have seen, the Greeks grew especially suspicious of the mysterious power of music to stir the emotions of its audience and to alter the conscious perception of the individual. These would increasingly be considered real threats to the state.

Both Plato and Aristotle were largely writing about what was quickly becoming a bygone era, about what made the “old” plays great—not about their contemporaries. Anderson and Mathieson describe Plato as “manifestly out of touch with his own times” (Anderson and Mathiesen 2017b), but Plato was also reacting to what he perceived to be the decay of the education system and culture of fifth-century Greece. Aristotle was somewhat more adaptive to his own times. Both Plato and Aristotle wrote descriptively about the past, but both also wrote prescriptively, prescribing what they thought good music, good theatre—and, by extension, good citizenship, should be.

At the end of the fifth century, in 404 bce, Sparta conquered Athens in the Peloponnesian War and the so-called Golden Age of Greece ended (Encyclopedia Britannica 2015). By then, the oral tradition that produced the great music-theatre of the fifth century was all but obliterated. Anderson and Mathieson report that Timotheus of Miletus had so altered the dithyramb by making the text an elaborate libretto, and adding frequent modulations to the musical accompaniment, that any possible connection to ethos was lost (Anderson and Mathiesen 2007–2016). Musicians were making up melodies and playing them with no regards for the words, and were often more popular than the poets themselves. Mathiesen asserts that, at least as far as the dithyrambists were concerned, the improvisatory ability of the performers became so popular that “the name of the aulete himself sometimes precedes that of the poet and choregos, and this provides further strong indication of the popularity of the virtuoso instrumentalists associated with … the dithyramb” (Mathiesen 1999, 81). But as far as Plato was concerned, and as Jamie James points out in his book The Music of the Spheres: “cultivated Greeks did not listen to purely instrumental music, but rather considered it to be only a vehicle for song—that is, poetry—or dance” (1995, 57).

Credit: Photo of a copy of Silanion’s Sculpture ca. 370 bce by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Accessed July 20, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Plato_Silanion_Musei_Capitolini_MC1377.jpg. CC-BY-2.5. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en. Adapted by Richard K. Thomas.

From the fourth century bce on there was a significant division between poet and composer. This may be attributed to several causes, beyond the obvious problems caused by written plays that were passed down in history, while unannotated musical compositions separated and were lost for all time. First, as drama and music became more sophisticated, it became increasingly difficult for one person to become accomplished in more than one area (see Chapter 1). Second, the drama was no longer considered to be strictly a teaching device, but was increasingly accepted purely as an entertainment. Third, these two factors together created a need for specialists who strove to appease an audience. Fourth, there was an increasing dependence on financial reward to attract new talent to the field. Henderson writes that these factors produced a revolution in art: “when the classical unity of Music was broken, the ‘music’ … was supplied by a professional engaged in the performance. The modern figure of the pure composer, who is neither poet nor player, was unknown to antiquity” (Henderson 1955, 400). New styles of accompaniment arose, such as the use of sound effects like wind, hail, rain, thunder and so forth. The organic unity that had once been the ideal, now took second place to pandering to public opinion.

Plato’s history of the musical revolution in the mid-fourth century bce relates the bastardization of style to the downfall of the democracy itself. And, just in case you think I’m kidding, consider this sample from Plato’s Laws:

let us speak of the laws about music—that is to say, such music as then existed—in order that we may trace the growth of the excess of freedom from the beginning … the directors of public instruction insisted that the spectators should listen in silence to the end; and boys and their tutors, and the multitude in general, were kept quiet by a hint from a stick…. And then, as time went on, the poets themselves introduced the reign of vulgar and lawless innovation. They were men of genius, but they had no perception of what is just and lawful in music … ignorantly affirming that music has no truth, and, whether good or bad, can only be judged of rightly by the pleasure of the hearer. And by composing such licentious works, and adding to them words as licentious, they have inspired the multitude with lawlessness and boldness, and made them fancy that they can judge for themselves about melody and song…. in music there first arose the universal conceit of omniscience and general lawlessness;—freedom came following afterwards, and men, fancying that they knew what they did not know, had no longer any fear, and the absence of fear begets shamelessness…. Consequent upon this freedom comes the other freedom, of disobedience to rulers; and then the attempt to escape the control and exhortation of father, mother, elders, and when near the end, the control of the laws also; and at the very end there is the contempt of oaths and pledges, and no regard at all for the Gods.

(Vol. 5, pp. 82–83)

Plato lamented the old school of the oral tradition, and the development of new styles in which music and drama gradually become separated. To understand Plato’s problem (and Socrates, since Plato often wrote in Socrates’ voice), one must understand how music shaped his core belief system. For Plato, the essence of the most fundamental entities in the universe all proceed in accordance with the harmonious nature of the universe as described by Pythagoras. Plato developed a “Theory of Forms” that attempted to explain universal attributes such as beauty in their exemplars. In Plato’s theory, for example, the beauty of Achilles or Helen would somewhat approximate examples of the ideal form of beauty. Plato’s theory eerily reflects the exemplar theory we examined in Chapter 10 that describes how the brain fires unique patterns of neuronal firings for each experience, yet how some aspects of those firings are similar or duplicated by other memories, creating categories. In Plato’s worldview, proportion and harmony, in the Pythagorean sense, are aspects of the first principle of everything, which Plato called “The Good.” So, in his Timaeus, Plato describes how the Demiurge (i.e., creator) created the world in strictly Pythagorean terms:

And he proceeded to divide after this manner: First of all, he took away one part of the whole [1], and then he separated a second part which was double the first [2], and then he took away a third part which was half as much again as the second and three times as much as the first [3], and then he took a fourth part which was twice as much as the second [4], and a fifth part which was three times the third [9], and a sixth part which was eight times the first [8], and a seventh part which was twenty-seven times the first.

Plato keeps manipulating the numbers until he comes up with the mathematical ratios necessary to produce an almost perfect major scale covering five octaves!

After this he filled up the double intervals [i.e. between 1, 2, 4, 8] and the triple [i.e. between 1, 3, 9, 27] cutting off yet other portions from the mixture and placing them in the intervals, so that in each interval there were two kinds of means, the one exceeding and exceeded by equal parts of its extremes [as for example 1, 4/3, 2, in which the mean 4/3 is one-third of 1 more than 1, and one-third of 2 less than 2], the other being that kind of mean which exceeds and is exceeded by an equal number. Where there were intervals of 3/2 and of 4/3 and of 9/8, made by the connecting terms in the former intervals, he filled up all the intervals of 4/3 with the interval of 9/8, leaving a fraction over; and the interval which this fraction expressed was in the ratio of 256 to 243.

(Vol. III, p. 454)

Now, it wouldn’t have occurred to anyone to actually “play a few bars of the World Soul on the lyre,” as James reminds us (1995, 48). It was “just a theory,” as we are fond of saying now. But Plato definitely connected the world soul to the soul of each individual, and, in doing that created a connection between the mathematics of music and the ethereal power that music has to influence and create human emotion, an awareness of the strange power of consonance and dissonance as we discussed in Chapter 8.

Music was, for Plato, and for Greek citizens, an essential element of education. In his Republic, Socrates gets Thrasymachus to admit that a musician is wise, and one who is not is foolish!

Socrates: |

And now to take the case of the arts: you would admit that one man is a musician and another not a musician? |

Thrasymachus: |

Yes. |

Socrates: |

And which is wise and which is foolish? |

Thrasymachus: |

Clearly the musician is wise, and he who is not a musician is foolish. |

Socrates: |

And he is good in as far as he is wise, and bad in as far as he is foolish? |

(Vol. III, p. 28)

Socrates goes on to suggest that a better education could not be found for heroes than in the two divisions of gymnastics for the body and music for the soul:

Socrates: |

And our story shall be the education of our heroes. |

Adeimantus: |

By all means. |

Socrates: |

And what shall be their education? Can we find a better than the traditional sort?—and this has two divisions, gymnastic for the body, and music for the soul. |

Adeimantus: |

True. |

(Vol. III, pp. 58–59)

For one thing, Plato lived in a time when music was still considered to consist of the inseparable elements of referential words and non-referential music, not as we defined it in Chapter 4. But Plato was keenly aware of this separation and spoke of it explicitly:

Socrates: |

And when you speak of music, do you include literature or not? |

Adeimantus: |

I do. |

(Vol. III, pp. 59)

But Plato also calls this combination of words and music, song, as we have throughout this book, and makes no distinction between the words that are set to instrumental music and words which are not:

Socrates: |

You can tell that a song or ode has three parts—the words, the melody, and the rhythm; that degree of knowledge I may presuppose? |

Glaucon: |

Yes, so much as that you may. |

Socrates: |

And as for the words, there surely be no difference between words which are and which are not set to music; both will conform to the same laws, and these have been already determined by us? |

Glaucon: |

Yes. |

Socrates: |

And the melody and rhythm will depend upon the words? |

Glaucon: |

Certainly. |

(Vol. III, pp. 58–59)

So, here we see Plato consciously reflect the definition of music we so carefully detailed in Chapter 4: the referential aspects of language and ideas that include the words, plots and stories of literature, and the non-referential parts of music, which include melody and rhythm. Sound familiar? Outside of this oddity of whether to include words in the actual definition of music, Plato shares our broader conception of mousikē—any activity governed by the Muses—in many ways, the same wide view that we have taken of “song” we first introduced in Chapter 7.

Plato understood that when you attach ideas to music, it can have a profound effect upon the listener. Plato really, really distrusted that special power of music. Like many philosophers of his and subsequent days, he needed to reconcile the undeniable power of music, idea and mimesis—especially when they got together in theatre—with the cultural milieu of his day. Isobel Henderson describes the situation: “It is true that to classical Greek minds music was like a second language, capable of expressing almost all that could be said in words, and of bringing out the moods or passions latent in them” (1955, 385). Plato was, in fact, suspicious of all the musical aspects of poetry, particularly rhythm and melody (line), because of the way these found their way into the human soul and affected a person’s ethos:

musical training is a more potent instrument than any other, because rhythm and harmony find their way into the inward places of the soul, on which they mightily fasten, imparting grace, and making the soul of him who is rightly educated graceful, or of him who is ill-educated ungraceful.

(Vol. III, p. 88)

The solution was to insist that music subordinate to language, and this was easy to justify. Since musical styles had evolved from the dialects of the various ethnic groups, these should only be employed as they best served the state. Or at least that would be the story that Plato would eventually advocate.

Plato first wanted to seriously control what sorts of things children learned in school, starting with the ideas in literature:

Socrates: |

And literature may be either true or false? |

Glaucon: |

Yes…. |

Socrates: |

The first thing will be to establish a censorship of the writers of fiction, and let the censors receive any tale of fiction which is good, and reject the bad … |

(Vol. III, p. 59)

Socrates: |

Some tales are to be told, and others are not to be told to our disciples from their youth upwards, if we mean them to honour the gods and their parents, and to value friendship with one another. |

(Vol. III, p. 69)

Then Plato insisted that students needed to be taught how to match the music to the text in the classical tradition:

Socrates: |

And the melody and rhythm will depend on the words? |

Glaucon: |

Certainly…. |

Socrates: |

The teacher and the learner ought to use the sounds of the lyre, because its notes are pure, the player who teaches and his pupil rendering note for note in unison; but complexity, and variation of notes, when the strings give one sound and the poet or composer of the melody gives another—also when they make concords and harmonies in which lesser and greater intervals, slow and quick, or high and low notes, are combined—or, again, when they make complex variations of rhythms, which they adapt to the notes of the lyre—all that sort of thing is not suited to those who have to acquire a speedy and useful knowledge of music in three years. |

(Vol. III, p. 84)

Because music was so powerful in stimulating emotions, Plato felt a strong need to ban any modes that did not promote a strong ethos or character disposition. Plato rejected both the bass Lydian and the tenor Lydian scales. These expressed “sorrow” and were “useless … even to women.” (!) Also out were the Lydian and the Ionian. These are the modes of drunkenness, softness and indolence, and “unbecoming the character of our guardians” (Vol. III, p. 84). This just left the Dorian—for times of war, which require the “strain of necessity … the unfortunate … and courage,” and the Phrygian, for times of peace, which demand “the strain of freedom … the fortunate … and temperance.”

In the color department, Plato would ban any instruments capable of producing the banned melodic modes, including many stringed instruments and the flute. Okay was the simple lyre and the pipe for shepherds in the country (Vol. III, p. 85). Also out were sound effects:

Socrates: |

Nor may they imitate the neighing of horses, the bellowing of bulls, the murmur of rivers and roll of the ocean, thunder, and all that sort of thing? |

Adeimantus: |

Nay, he said, if madness be forbidden, neither may they copy the behavior of madmen. |

(Vol. III, p. 81)

Plato wasn’t so sure about which rhythms expressed which emotions (he decided to leave that job to his contemporary, the Greek music theoretician, Damon). But he was sure that complex rhythms would lead to no good. Simple rhythms were “the expression of a courageous and harmonious life… (and) grace or the absence of grace is an effect of good or bad rhythm” (Vol. III, p. 85).

Plato, of course, was writing in an era in which the old laws of music and language intrinsically interwoven into poetry, were no longer followed. Plato felt an increasing need to address that growing trend to ignore the important moral and ethical ideas that had been embedded in poetry and Greek theatre, and, instead, to simply create music for its own sake. By the time he wrote his Laws, Plato had refined his thinking that music was divinely transmitted by the Muses through the composer to the performer to the audience like the rings of Heracles’s magnet:

Athenian Stranger: |

Do we not regard all music as representative and imitative? |

Cleinias: |

Certainly … |

Athenian Stranger: |

And will he who does not know what is true be able to distinguish what is good and bad? |

(Vol. V, p. 47)

Plato argued that if one did not truly know what the thing was that was imitated, that one could not be sure that what was imitated was good. And if one imitated bad things, then one could inadvertently transmit and incite a “bad” disposition. So, there must be laws to prevent musicians from imitating any old thing. It would not be enough to simply assert that one was “inspired by the Muses”:

Socrates: |

Then let us not faint in discussing the peculiar difficulty of music. Music is more celebrated than any other kind of imitation, and therefore requires the greatest care of them all. For if a man makes a mistake here, he may do himself the greatest injury by welcoming evil dispositions, and the mistake may be very difficult to discern, because the poets are artists very inferior in character to the Muses themselves. |

(Vol. V, p. 48)

Plato adopted the emerging conception of mimesis, an admittedly ambiguous term even in fourth-century Greece, to explain human intervention in the creative process. This included so many of the modern inventions that Plato protested against, instrumental music, the indiscriminate mixing of modes and language, unorthodox use of musical instruments, etc. However, according to Anderson and Mathiesen, Plato

repeatedly failed … to reconcile the component of musical ethos which is mimetic of human attitudes with the rhythmic and melodic component of ethos…. He saw music as a vehicle of ethos through mimesis; and he held to this practical view even if it had to be at the expense of Pythagorean theories of number and cosmic harmony.

(Anderson and Mathiesen 2007–2016)

For Mathieson, Plato’s interest in musical mimesis had to do solely with the ability of music to affect ethos. For Plato, music could only be mimetic that joined and carried text. Instrumental music was not mimetic.

Plato felt so strongly about this that he wanted to ban any advances in music. He thought that unregulated departures from approved music would destroy civilization (Vol. III, p. 112). But the cat was already out of the bag in ancient Greece: composers and performers were all making music with no thought of what they were “imitating.” They were simply expressing themselves, allowing the inspiration of the Muses to pass through them to the listener. Plato is not the only major public figure to make this claim throughout history: jazz, rock and roll, hip hop and many other forms of music have all been accused of portending the end of civilization.3 Here, in a very real and somewhat elegant argument, was an exploration of the effects of conditioning using implicit memory as we discussed in Chapter 10.

The concept of mimesis and ethos remains controversial. Some, such as Gerald Else, argue that the basis of mimesis lies in imitation: “What we can infer with some confidence is that the original sphere of mimesis—or rather of mimos and mimeisthai was the imitation of animate beings, animal and human, but the body and the voice (not necessarily the singing voice).” But if we follow this argument, we must simultaneously consider the evidence presented earlier of the beliefs that drove animism, in which someone who could imitate, such as an animal or deceased human, was thought to be possessed by the soul of that person. At what point did the shaman stop imitating animals and humans, and truly believe that they were channeling the souls of animals and humans? In such a world, what does it really mean to “imitate”? Else appears to recognize this when he says:

the key to the puzzle … is the psychological premise (that) the thing which dramatic imitation (in Plato’s sense, i.e., impersonation) and musical imitation have in common is assimilation of one’s soul to the character of the person or “life” which is imitated…. Plato brought together mimesis, with its dramatic connotations, and the concept of assimilation which was at home in music.

Else suggests that the unique conception behind this complex interaction between music, idea (language) and mimesis was Plato’s (Else 1958, 85).

Hermann Koller, on the other hand, argued that the origin of the word mimesis lay in the primitive expressive power of music, and that imitation was a much later development. Mimesis had to do with those rings of Plato, that unique ability of humans to express themselves and incite in others similar states through the experience of music. Koller argues that Plato introduces this concept specifically so that he could use its derivation to condemn certain types of poetry, in the same sense that we have explored how Plato felt a strong need to use government to control the extraordinary power that music had on an individual (Else 1958, 84).

In any case, we find a culture squarely becoming aware of the unique power of music, and attempting to understand it, and even to develop governmental systems to control it. The core concept is that simply translating the term mimesis to mean imitating something undermines both the Greek worldview and the very fundamental conceptions we have examined in this book. Even Merlin Donald’s discussion of mimesis as an evolutionary adaptation, as we discussed in Chapters 5 and 6, implies not just the imitation of an action, but the internalization of the action itself. Music is not simply an imitation of someone else’s colors, rhythms, melodies and so forth. The music experience involves the transmission of the actual experience of music from the composer through the performer and into the listener. It involves the powerful evolutionary physiological and psychological systems that we explored in Chapter 9, often without our conscious awareness of the process. Successful mimesis unleashes something almost frighteningly more powerful: the ability to transport the listener into the world of the performer, whether strictly emotional and temporal in the case of instrumental music, or more powerful and complete when ideas become attached to music in song, and actors bring the characters to life in theatre. This process seems to occur in much the same way that shamans embodied the souls of passed ancestors as we explored in Chapter 9 and that developed into animism in Chapter 10. And that was precisely what Plato was worried about.

This problem of imitation versus mimesis is not simply one that the ancient Greeks wrestled with in order to form a better democracy. It lies at the very core of the art of theatre, and, inasmuch as theatre is a type of music, at the core of the challenge facing the sound designer and composer. Remember that we examined the biological base behind true mimesis and indicating in Chapter 8. In acting as well as composing, there are two ways to get at an emotion: by imitating the emotion, or by genuinely generating the emotion. Twentieth Century Fox acting coach Scott Rogers describes the problem of indicating: “One of the most common problems for actors tends to be the temptation to indicate emotions. There is only one way to convincingly act real emotions in film, and that is, to actually FEEL the emotion” (Rogers 2014). In my classes, and throughout this book, we have offered a series of exercises (Things to Share) in which students attempt to isolate a particular design element (e.g., color, mass, rhythm, space, line, or texture) for a range of emotions (love, anger, fear, joy, and sadness). They then attempt to incite that emotion in the listener by manipulating only one specific design element. But in every class, we eventually get to the discussion about whether the example is truly “inciting” the emotion, or simply representing or “indicating” the emotion. We accept the reality that there is a lot of indicating, especially among beginning composers and sound designers who are still learning their craft.

It might be useful to consider an example of a time when I first became consciously aware of the difference between the two concepts, imitation and mimesis. I was composing a score for our original work, The Creature, and working with my good friend and former student, Cory Kent. This was in the 1990s, and the band Limp Bizkit was very popular. We had conceived of the production stylistically as a series of MTV music videos, and Cory and I wanted to explore Limp Bizkit’s style. In theatre, unless you are really famous like Stephen Sondheim or Philip Glass, you will have to learn to compose in a variety of styles, so I knew just what to do. The first thing we did was to simply mock up a Limp Bizkit song—imitate it. Then, as is typical for me, we threw that away, and worked to create in that style, but from the honest emotional well of the scene. But we reached an impasse. We could not find a drum fill for a particular moment in the sequence. Finally, I simply rewound the sequencer and just pounded out an almost totally impulsive explosion of random drums. It worked. We edited a little, took a few bad hits away, quantized a little more to tighten up the style, and suddenly we had the exact emotion the moment required. I was amazed how, when I let my conscious self go, and immersed myself in the moment, I could trust I had enough craft to channel my impulses through the style of the piece.

I learned a valuable lesson from this. Often times now I’ll create an underscore or a strong emotional musical moment in a scene by simply turning on the recorder, finding a versatile patch (strings with a velocity-controlled variable attack work well), and just playing in the emotion as much as I can for as long as 20 or 30 minutes, typically around a short motif of a few notes. Of course, I’ll drift in and out of the most powerful and honest expression of the scene. But then I can come back and edit virtually all the bad stuff out, keep the honest and true moments, assign colors to various parts, flesh out the orchestration and so forth. I do all of this knowing that I’m building on a true and honest foundation in which I’m not imitating an emotion, but living in one.

Composing sound scores without indicating requires a rather complete mastery of one’s craft. We visited this subject in Chapter 10 when we talked about how tying one’s shoes passed from a consciously recalled imitation we called explicit memory and into the unconsciously recalled implicit memory where we no longer imitate, but simply tie our shoes. Let’s consider a couple of examples. Having worked with a number of international students, I always check in with them to find out when they started thinking and even dreaming in English rather than mentally translating into their native language. Typically, this seems to take place about four to eight months after they become totally immersed in the language. They have mastered conversational English, and now they can simply exist in it. In sports, If I were to teach a child how to hit a baseball, I would show the child how to hold the bat, how to swing it, etc. The child would then imitate me. At first, the child’s imitation would not be very good. Flash forward 20 years to the child now playing in the major leagues. He no longer imitates swinging the bat. The craft of swinging a bat is so deeply ingrained that the major league slugger is no longer imitating. Instead he feels it deep inside, and incites that musical motion of a great swing from deep within—like the source magnet of Plato’s rings. At that point, we could hardly say the man was imitating. Although he got to where he was through imitation.

Most musicians have the same experience learning to play piano. At first, we imitate, by reading notes on a page, and struggling to get our fingers to conform to the patterns the composer indicated. But in every piece, there comes a time when we have stopped doing that—we’ve learned the piece—and then we just start being the piece, fully immersed in its emotional journey. For example, I can attest to having emotion incited in me when I learned to play Chopin—the moment in which I stopped trying to imitate anything, and just became immersed in the music, genuinely feeling the strong emotions Chopin elicits. As an audience member, I’ve spoken quite a bit in this book about memorable moments where I’ve felt the emotions of the performance deeply. But the problem with teaching scoring is that we are asking composers to write to an emotion. We are asking them to empathize with a character, scene or theme of a story rather than merely sympathize. That turns out to be very hard to do for some composers. It requires an actor’s process coupled with the craft and genius of the composer.

As one perfects one’s craft, one no longer concentrates on imitation; instead one works to develop the emotion, let it out through music, where it can then incite a similar emotion in both the actors and the audience. Indicating in sound scores, is perhaps as distracting as indicating in acting. But young sound designers and composers should not shy away from learning the “craft” of composing to a specific emotion through imitation, in the same way that they would not shy away from learning how to hit a baseball properly.