p.117

3.5 Promoting, informing, and identifying

The case of Foody, the humorous mascot of Expo Milan 2015

Carla Canestrari and Valerio Cori

Expo Milan 2015: between communication and business

Since the early editions of the Great Exhibition of Industries of All Nations, such as the famous one held in London in 1851, the main goal of every Expo has been to give nations, politics, the business world, and society a shared space in which to discuss and cooperate in a crucial area of interest common to all the participating parties.1 Topical themes and subjects are discussed during each edition of Expo. For example, in the earlier editions, the main subjects were related to technology, as the industrial revolution and colonialism were the topical subjects of that period. Later on, even after World War II, human progress and international dialogue have taken centre stage at every Expo, in addition to technology.2

With the beginning of the new millennium, a number of important issues have raised common awareness about the importance of finding strategies to make progress and human development more sustainable.3 In particular, in this day and age, malnutrition is still a serious problem for a large number of people (estimated at 805 million). Nevertheless, the increasing world population and the relative growing demand for food raise many questions about resource management.4 The theme chosen for Expo Milan 2015 was therefore “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life” and the event was devised to give nations, the business world, politics, and society in general an opportunity to discuss and share potential solutions for answering important questions in this field, such as:

• Is it possible to ensure access to sufficient, good, healthy, sustainable food for everyone?

• How can we ensure that everyone has access to healthy food?

• How can we use resources in a sustainable way?

• How can we reduce waste?

• How must our need for wholesome, healthy food influence our choices in energy production and the use of natural resources?5

The last edition of Expo was a “mega-project” as its theme touched many sectors and the event was designed to have a heavy impact on economics and society.6 Since Expo Milan 2015 was such a huge event, it offered a platform and a shared space in which nations from all over the world could address the above-mentioned questions.

Expos are part of the business tourism sector7 and they are an “important element of industry marketing communications”.8 The impact of these mega-events is a very complex matter.9 Nonetheless, the popularity of these special events is increasing and their organisers are challenged to refine the communicative strategies used10 in order to engage attendees emotionally, affectively, and cognitively.11 Therefore, communicating effectively and strategically is clearly of key importance.12

p.118

To get an idea of the communicative impact of the last edition of Expo, it is sufficient to consider that the event witnessed 150 participants organising approximately 5,000 events for more than 20 million visitors, in 184 days of exposition.13 The communication strategies for the event targeted both the visitors attending it and those who participated in it, arriving from all over the world. Due to its nature, the exposition was an opportunity for nutrition experts and researchers to meet, and it also had a strong educational slant. In fact, its visitor categories ranged from business people and experts to families and schools. Therefore, it seems reasonable to wonder how Expo reached these many different kinds of people. How did it succeed in communicating its themes, values, and knowledge? There are many answers to these questions, one of which is the use of a brand mascot, named “Foody”.

Why Foody and his friends?

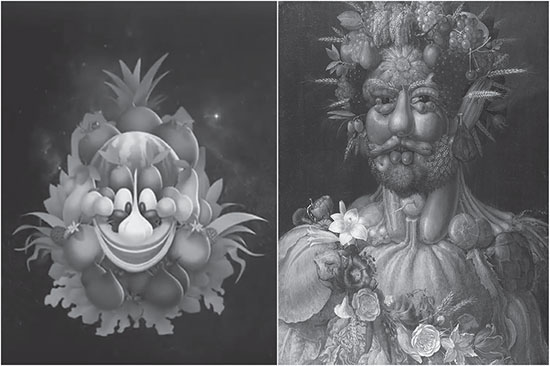

Foody is a colourful smiling face inspired by the work of Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526–1593), famous for his grotesque portraits created by wittily assembling realistic elements such as objects, vegetables, fruits, or flowers, as shown in Figure 3.5.1, right. Foody is composed of 11 anthropomorphised fruits and vegetables (i.e. his friends) and metaphorically represents the synergy of a community composed of the 140 countries from all over the world that participated in Expo Milan 2015.14 The fact that they are fruits and vegetables immediately recalls the subject of the exhibition, namely healthy nutrition. Foody is not only a static mascot: he and the various characters composing him also come to life as lively dynamic creatures thanks to the animation project created by “Disney Italia”.15 Each fruit or vegetable that composes Foody’s face is introduced in an animated cartoon, defining the character and conveying some of the topics on which Expo Milan 2015 focuses (“Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life”). The humorous communication performed by Foody’s friends in the animated cartoons is the focus of our analysis.

Figure 3.5.1 Foody’s face (left)16 and the famous painting “Vertumno” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1591) (right)17

p.119

Being a mascot, Foody and his friends convey several communicative functions, such as: entertaining,18 eliciting positive responses,19 obtaining easy acceptability, prolonging association and recall with the brand they represent,20 grabbing attention, connecting with a type of personality in order to reach a certain audience,21 and making “the ideas promoted by the mascot [. . .] less alien”.22 In fact, brand mascots are acknowledged as having the potential to ensure that the values and characteristics of a corporation immediately spring into the minds of their perceivers (consumers and stakeholders). This has been shown to be particularly true in the case of anthropomorphised mascots, which are perceived by consumers as having specific personalities and ethical values.23 At the same time, they are perceived by the organisation members as “organizational totems”,24 and the consolidators of an identity practice.25 Using a mascot is a type of communicative strategy that is increasing with the rise of social media.26 There are many reasons for choosing a brand character in order to communicate. Particularly, this is the case for companies trying to establish a lasting connection with the audience based on loyalty and brand advocacy,27 as consumers are able to identify with the values and personality embodied by the brand character.28 Brand mascots can be useful within organisations too: they have rallying power, they help to define and differentiate the organisations they represent from others and they can also have a role in orienting strategies.29

The Arcimboldesque figure of Foody makes the anthropomorphic nature of this brand mascot quite clear. Since anthropomorphism can be considered as a “pervasive, perhaps universal, way of thinking”,30 it can be a powerful tool for communication due to its “attention-grabbing power and its inferential potential”.31 Anthropomorphism is also one of the key components of a brand’s active role in building a relationship with the customer.32 Moreover, consumers’ responses can be affected by this “process of assigning real or imagined human characteristics, intentions, motivations or emotions to non-human objects”.33 The effectiveness of anthropomorphism can be enhanced by proto-typicality and schema congruency, as in the case where the mascot is an animal that shares some features with humans (e.g. bipedalism).34 As far as Foody is concerned, there are a number of fruits and vegetables that share some features with humans and this makes Foody an anthropomorphic mascot.

Based on the facts stated above in relation to the communicative impact of mascots in general, and in particular anthropomorphic mascots, it is important to focus on the communicative aspects of Foody. Specifically, at first glance, the elements that characterise the mascot are humour and fun, distinguishing him from previous Expo mascots. For example, the only humorous aspect of Haibo, the mascot of Expo 2010, held in Shanghai (China), was that he personified the Chinese ideogram “Ren”, which means “people”.35

The same is true for Kiccoro and Morizo, two anthropomorphic creatures of the forest, who were adopted as the official mascots of Expo 2005, held in Aichi (Japan).36 They have a grandfather–grandson relationship and this contributes to their anthropomorphisation.

Foody shares the characteristics of personification and anthropomorphisation with his precursors, but due to his Arcimboldesque inspiration, he is markedly funny, both when we consider him as a whole and when we consider him “piece by piece”. The first funny thing that pops up is that each singular element is a complete structured form in itself (i.e. a Gestalt) and at the same time it plays a specific role in Foody’s face (e.g. a bulb of garlic is his nose, a banana his smiling lips, and so on). Foody’s face is made of the following 11 sub-characters, also referred to as “Foody’s friends”: an orange (Arabella), a pear (Piera), a pomegranate (Chicca), a banana (Josephine), a corn cob (Max Mais), a watermelon (Gury), a bulb of garlic (Guagliò), a fig (Rodolfo), a mango (Manghy), and an apple (Pomina). The names of the various components of Foody’s face were assigned by a group of Italian students who participated in a public competition designed to raise the awareness of young students (from kindergarten to high school) about the themes of Expo. One of the activities involved inviting the students to invent names for Foody’s friends. The best names suggested were then chosen and used.37

p.120

Each friend comes to life in 11 short cartoons made by Disney Italia.38 The main characteristic of these cartoons is that Foody’s friends behave as if they were humans and not fruits or vegetables. In this way, the anthropomorphic figures look much more human and realistic as they are set in a dynamic background that asserts their identity.39

It is acknowledged that there are several reasons for favouring the decision to use humorous communication. Humour can be used for the purposes of persuasion, particularly in mass communication,40 to build group identity and strengthen group cohesion,41 to tease,42 and to amuse.43 As humour and fun are the salient features of Foody, our goal is to identify the types of messages and functions conveyed humorously in the 11 short cartoons starring Foody’s friends.

Humorous communication: a qualitative analysis

Aims

The general aim of the paper is to show how humour can be used in association with a mascot and to discover the purpose for which it can be used. This goal can be achieved by analysing the humorous strategies associated with Foody and his friends and their communicative functions. In particular, our qualitative analysis aimed to pinpoint the humorous occurrences in the 11 cartoons, analysing the thematic issues on which these focus, and inferring what the authors of the cartoons hoped to gain by using humorous communication.

Method

The 11 short cartoons (described in the following section) were downloaded and the instances of humour contained therein were located by searching for humorous incongruities. Incongruity is acknowledged as being the key element of humour and it has been defined and approached in several ways within the literature.44 Generally speaking, the key element of humour is the presence of an incongruity: humour occurs when “something unexpected, out of context, inappropriate, unreasonable, illogical, exaggerated, and so forth”45 happens and “when the arrangement of the constituent elements of an event is incompatible with the normal or expected pattern”.46 The general framework of humour as a concept derived from incongruity, when developed from the cognitive-linguistics47 and cognitive-perceptual perspectives,48 provides us with useful tools for identifying humorous occurrences in the corpus.

According to the cognitive-perceptual perspective, humorous experiences are based on the perception of an incongruity and its cognitive elaboration. For example, the “weight judging paradigm”49 demonstrates experimentally how the perception of pure incongruity can be the basis for amusing experiences: participants were asked to lift a series of weights, unaware that only the last weight was much heavier (or much lighter) than the previous ones, and so laughed when they lifted the last weight. This humorous response is due to the fact that the participants perceived a considerable incongruity between their cognitive expectations (built on the basis of the previously perceived weights) and the facts. According to the cognitive-perceptual perspective, the perception of an incongruity can also be elicited by jokes and texts playing on sensorial (i.e. perceivable) aspects.50 In these cases, it has been demonstrated that the perception of a humorous incongruity is facilitated when it lies between elements that are clearly contrary to one another (global contrariety), rather than when they either differ too much (additive contrariety) or too little (intermediate contrariety), as in the following joke:

p.121

Yesterday at school we celebrated my classmate Marcellina’s birthday so I gave her a cherry and she kissed me to say thank you. Today I gave her a watermelon . . . . But she didn’t get it!51

Global contrariety is embodied by two elements that are invariant in many respects and opposites with reference to a key dimension. In the above joke, a cherry, and a watermelon are globally contrary to one another in terms of size yet at the same time they both share many other invariant properties (they are both fruits, round, juicy, and so on). In this case, the relationship of contrariety between the two elements is evident. Replacing the watermelon with an apple, or a big polystyrene box elicited lower levels of amusement.52

The cognitive-perceptual perspective was selected as the tool used to identify perception-based humorous occurrences in our corpus, based both on the perceptual aspects of the same, given that the corpus is characterised by the presence of objects (i.e. fruits and vegetables) with strong sensorial elements (olfactory, tactile, visual, and relative to taste), and on it largely being based in a visual dimension (as it is a series of animated cartoons).

We also used tools based on the cognitive linguistic perspective in a bid to find other types of humorous incongruities. According to the cognitive linguistic approach to humour, which is particularly suitable for humorous texts based on linguistic ambiguity and double meaning, the incongruity derives from the contrast between the explicit and hidden interpretations of the text. For example, the punchline of the above-mentioned joke forces the reader to switch from a childish situation (i.e. explicit meaning of the text) to a sexual innuendo (i.e. hidden interpretation of the text). In this case, the text contains a “covert incongruity” and the reader/listener is forced to backtrack through the whole text to decipher the humorous logic (i.e. resolution) that leads to the hidden interpretation of the text. The incongruity is not sudden and lies in the comparison53 of the two sets of meanings unveiled by means of the punchline. In this sense, the incongruity refers to the incompatibility of two frames of reference,54 or to the script opposition as conceptualised by Attardo from a cognitive linguistic perspective.55 The replacement of the initial frame of reference, usually more commonplace (i.e. familiar/salient) with a second one (i.e. one that is less familiar/salient), resolves the incongruity and produces the humorous effect.56

As exemplified by the short analysis of the above-mentioned joke, the two frameworks used to identify humorous incongruities, namely cognitive-perceptual and cognitive linguistic perspectives, are not mutually exclusive. As a result, a humorous occurrence can be detected according to both of them, when it is based on both perceptual and covert incongruities.

Once the humorous occurrences were pinpointed according to the theoretical tools mentioned above, the messages (i.e. the issues on which the humorous communication revolves around) and the communicative functions (i.e. the communicative acts) associated with them were analysed. To serve this purpose, we applied multimodal discourse analysis57 for the following reasons, dictated both by our corpus and our aims. Communication through technology is a relevant domain for multimodal discourse analysis58 and our corpus fits into this domain. Moreover, multimodal discourse analysis is particularly apt when it comes to capturing the communicative acts (i.e. functions) in texts made using different modes of communication (e.g. verbal and non-verbal texts), such as in our corpus.59 For example, a multimodal analysis, carried out on a number of visual commercials, which are composed of visual and non-visual modes, revealed that “boundary marking, attributing qualities to entities, calling to attention” are some of the communicative functions fulfilled via multimodality.60 Finally, this framework approaches discourse as a global communicative event.61 In other words, a discourse is considered as a Gestalt and this is in line with our intent to focus not only on the potential humorous events occurring second by second, but also on humorous aspects emerging from a global analysis of each cartoon.

p.122

Corpus

The analysis focuses on the 11 short cartoons about Foody’s 11 friends. Each cartoon revolves around one or more of the problematic issues chosen to characterise the last edition of Expo (e.g. unhealthy nutrition, food and energy waste) and suggests possible solutions (e.g. eating and drinking healthily, frugality, recycling). This common structure makes the 11 cartoons an appropriate corpus which can be analysed to discover how the thematic issues of Expo Milan 2015 are approached via humour.

Each cartoon lasts approximately 2’.30’’. The 11 cartoons run for a total of 27’.06’’ and they have been viewed 389,558 times to date (although other viewings could follow, since the cartoons are still available on YouTube).62

The 11 cartoons share the same setting and structure. They begin and end with the same leitmotif, lasting approximately 20 seconds. What happens in the middle can be divided into three phases. In the first one, a talent show setting appears, with a stage and a screen behind it. On that screen, Foody’s face appears and quickly disappears when the main character takes to the stage. In this phase, Foody introduces the character and his voice is provided by Claudio Bisio, a famous Italian presenter of comedy shows. The character appears on the stage, does not speak but moves his body. After approximately 1 minute, a brief report on the character’s biography is shown on the screen behind the stage, and this is the second phase. After approximately 50 seconds, the third phase begins: the focus is on the stage, where the character performs a skill test, a common occurrence in talent shows.

Findings

The tools of analysis described in the method section were applied by the first author of the paper to the dataset and the identified humorous occurrences were verified by the second author. In this paper, we report on the findings pertaining to the humorous occurrences upon which both analysers agreed. As pointed out in the previous sections, the aim of the paper is to focus on the possible humorous strategies that can be associated to a mascot like Foody and his friends and their communicative functions. Therefore the results of a qualitative analysis of the humorous occurrences, and not their frequencies, are provided.

Globally, the 11 cartoons share the pervasive use of humorous communication, embodied in several strategies. These include the personification of Foody and his friends, a key feature in each second of the 11 cartoons. In addition, the following humorous strategies can be found spread throughout the cartoons: incongruity-resolution forms of humour and pure humorous incongruities. In the first category, there are double meanings, allusions, verbal irony, puns, wordplay, and global contrariety-based incongruities. In the second one, there are examples of nonsense and global contrariety-based incongruity with no resolution.

p.123

For the sake of clarity, the results of the analysis conducted are reported following the three phases that structure each cartoon, as described in the previous section. In the first phase, a character, moving silently onto the stage, is introduced by Foody’s voice over. As a consequence, Foody performs verbal humour and the character performs non-verbal humour. In this phase, we found occurrences of humorous incongruities based on sensorial or non-sensorial aspects, followed only in some cases by a resolution. The humorous messages mostly convey information about the vegetable/fruit in question, and sometimes aspects related to the character. In the first case, the main function associated with the humorous mode of communication is informing the audience about specific qualities of healthy food (i.e. fruits and vegetables), in the second case the main function is amusing the audience and promoting a funny image of the character.

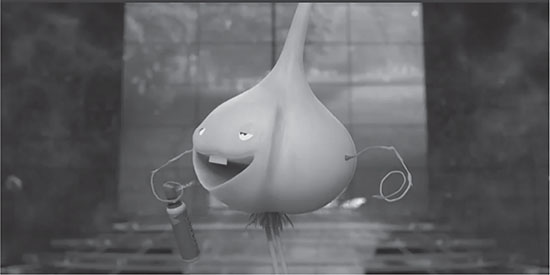

For example, when Guagliò (the bulb of garlic) sprays perfume around his face he is playing on the sensorial contrast between a good and bad smell and humorously alluding to a salient feature of garlic (see Figure 3.5.2). In this case, non-verbal humour playing on the perception of contrasting sensorial aspects is used, with the aim of drawing the attention to a specific quality of a type of healthy food. A similar aim is achieved via verbal humour in the following example. When Foody introduces the pop musician Max Mais (a corn cob), he says: “he is the king of Pop . . . corn”. Getting this joke means comparing the commonplace meaning of “pop” as the abbreviation of “popular music”, with the intended meaning “burst”, perfectly coherent with a corn cob. The function associated with this humorous occurrence is promoting a quality (specifically, a culinary one) of the vegetable in question. Another function of the humorous occurrences in the first phase of the cartoons is amusing the perceiver for the sake of amusement. This function is usually associated with the introduction of qualities related to the character, more than qualities related to the vegetable/fruit on stage. For example, Foody says: “Rodolfo the fig is so cool” (“Che fico, Rodolfo fico”). This humorous occurrence plays on the Italian homonymy between “fico” as “fig” and “fico” for the slang meaning of “cool”. The incongruity between the two frames of reference conveys a humorous message aimed at introducing a quality of the character (Rodolfo) rather than one pertaining to the fruit (the fig). In this case, the elicitation of amusement and humour is not supposed to inform the audience about the sensorial, historical, geographical, or culinary qualities of figs but to elicit humour and amusement per sé.

Similarly to the first phase, in the second phase we found verbal and non-verbal occurrences of humorous incongruities based on sensorial or non-sensorial aspects, followed only in some cases by a resolution. In addition to messages conveying information related to the fruit/vegetable or the character on stage, we also found a new type of message delivered via humour, namely messages linked strictly to the thematic issues of Expo Milan 2015. This category characterises this phase and we report on the analysis of a couple of examples that also show different modes of communication and humorous strategies. The first case we would like to examine comes from the cartoon featuring Arabella (an orange), who undergoes several beauty treatments, while neither changing her diet nor playing sports. Foody comments on Arabella’s behaviour negatively, using a simile: beauty treatments on their own are as useful as soup forks. This verbal humorous case plays on sensorial properties eliciting the perception of a global contrariety: solid and liquid are the two extreme properties of the same dimension (i.e. consistency) epitomised respectively by forks (used for solid food) and broth (that requires spoons to be eaten). At the same time, forks and spoons share several features: they are both small, they are pieces of cutlery, made of the same material, lightweight, and so on and so forth. The same can be said for solid food and broth: they are opposite in terms of consistency and they share invariant properties (in that they are both types of food). The coexistence of opposite and invariant properties makes this case an example of humour that plays on global contrariety. From the communicative and functional points of view, the message promoted by the simile presented by Foody is strictly linked to healthy nutrition. The amusement associated with this humorous case is designed to make people think about bad habits and good dietary practices. Another set of humorous examples focusing on one of the thematic issues of Expo Milan 2015 and promoting good practices is in Max Mais’ cartoon. The character performs exaggerated activities that are humorous in that they are the opposite of the expected or normal behaviour. For example, when he leads a non-sustainable lifestyle, he uses a high fashion car that burns too much petrol simply when moving from one room to another in his house (Figure 3.5.3, top). After his conversion to recycling, he uses a broken shoe as a plant vase, a cathode-ray tube TV as an aquarium, an old suitcase as a bathtub (Figure 3.5.3, bottom). These humorous exaggerations convey the message that recycling is a better practice than wasting and the function associated with it makes people think about environmental problems – derived from malpractices – and possible solutions.

p.124

Figure 3.5.2 Humorous incongruity playing on olfactory perception63

Figure 3.5.3 Two extreme examples of opposite behavioural patterns in the cartoon with Max Mais64

p.125

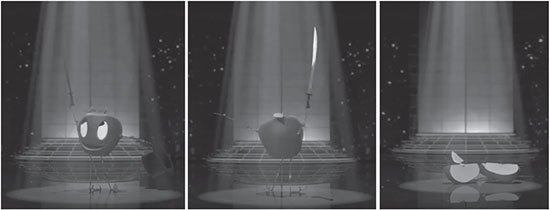

Finally, the cartoons end in the third phase. The consistent humorous strategy of the third phase, which is also a new one in comparison to the previous phases, is the clown-like performances of the characters in each cartoon. For example, Pomina, the apple, casts spells and ends up in four slices after having inserted a sword in her mouth (see Figure 3.5.4). Max Mais, the corn cob, makes a big soap bubble that swallows him up and makes him float in the air, until he damages the chandelier and the resulting sparks transform him into popcorn. The recursive humorous pattern in this last phase of each cartoon is always linked to the character and aims to show his or her clumsiness. Eliciting humour and amusement per sé is the main function of this kind of humorous mode. In this phase of the cartoon, there are few occurrences of verbal humour, mainly based on the incongruity-resolution paradigm, always performed by Foody. Also in these cases, the humorous messages are designed to promote a clumsy and funny picture of the characters, for the sake of amusement.

Figure 3.5.4 Clownish performance by Pomina65

p.126

To sum up, the main results of the descriptive analysis are as follows: (1) the humorous strategies vary from verbal to visual and sensorial-based humour, and from pure incongruity to incongruity-resolution-based humour; (2) the issues on which the humorous occurrences play range from the thematic issues of Expo Milan 2015 (e.g. health, nutrition, recycling, eco-sustainability) to the sensorial, historical, geographical, or culinary qualities of the specific fruits and vegetables and also to the anthropomorphic qualities of the characters; (3) depending on the issues on which the humorous occurrences focus, different functions emerge, such as promoting good practices, informing the audience about the benefits of healthy food, building characters’ identities, or simply amusing the audience for the sake of entertaining.

Conclusions and discussion

In order to create deep, meaningful, and long-term relationships with customers, companies refine their communication strategies.66 One of the most topical strategies is the use of brand mascots, which can serve as tools to capture the target audience’s attention, obtain good acceptability of the products, advocate a prolonged association with the brand, or recall it.67 The use of Foody to promote Expo Milan 2015 is perfectly in line with these purposes. The point of the analysis we have carried out on the corpus was to describe some of the communicative aspects it contains. In particular, we have striven to identify the messages and values conveyed by the humorous strategies and define their communicative functions.

Starting from the general framework of incongruity theories of humour, approached from the cognitive linguistic and cognitive-perceptual points of view, we identified humorous incongruities and analysed whether these were followed by a resolution or were based on sensorial aspects. The resulting patterns are epitomised in different humour strategies and modes, such as jokes, wordplay, exaggerations, non-verbal behaviours, and so on. We have shown that in some cases, these humorous occurrences have an informative value. Specifically, they communicate certain properties of the fruits and vegetables involved in the cartoon. They served to draw the attention to healthy nutrition and the values related to it. This result is consistent with Meyer’s approach to the functions of humour: incongruity-based humour can be used to clarify an issue and, at the same time, differentiate the points of view involved in it.68 Humour, even a humorous line, can be used to clarify a point of view in a creative and memorable manner, since the message is presented in an unexpected and incongruous way. Moreover, humour can serve to reinforce social norms and emphasise an expected behaviour, rather than focusing on the seriousness of the violation.69 In the case of Foody, we showed some humorous occurrences that have the function of clarifying, introducing, or reinforcing a number of good habits related to nutrition. In a sense, some of the humorous occurrences were also construed specifically to differentiate between two behavioural patterns (e.g. unhealthy vs healthy nutrition habits, dis-respectful vs respectful attitude towards the environment) yet in a mild way (i.e. without resorting to aggressive forms). For example, some of Foody’s humorous lines were designed to differentiate healthy from unhealthy food, in a communicative form that was not aggressive at all. Furthermore, humour, by means of differentiation, can serve to objectify an inadequate aspect and manage it.70 It seems realistic that the creators of Foody wanted to make people recognise their own bad nutrition habits and render these laughable in order to promote change.

p.127

We also found some cases where humorous occurrences had a more playful value. This type of occurrence was useful for telling amusing stories related to Foody’s friends and describing their personalities in order to make them look more human and realistic. As we noticed in the theoretical section, anthropomorphism is a feature that accompanies Foody’s humour and amusement in order to make a stronger connection with the audience. Brands are seen more favourably when an anthropomorphic advertising campaign is used, as shown by Patterson et al.71 Therefore, we can conclude that humour functions to enrich anthropomorphism in Foody. In fact, showing Foody as having a sense of humour, which is considered as a desirable characteristic in interpersonal relationships,72 surely contributes to making this mascot more human. Telling funny anecdotes about Foody’s friends helps to create their stories and build their identities. As a result, the referent anthropomorphic figure appears more realistic to consumers.73

In addition, it is worth remembering that humour can also be a good tool for advertising communication: advertisements based on a humorous communication are easily recalled74 and can be perceived as more appealing.75 We can suppose that the decision to make Foody incorporate humorous elements was taken with a view to making the whole Expo communication campaign more attractive. It could be interesting to test this kind of hypothesis with a survey or with an experimental design capable of capturing how a particular sample of the audience can recall the campaign or find it appealing.

The data under consideration in this study are examples of mass media communication; therefore, the cartoons were obviously created with the intention of generating a number of effects on the audience. However, the focus of the analysis was on the cartoons and not on the audience. In other words, by applying the qualitative tools provided by multimodal discourse analysis, we could depict a reliable picture of the communicative functions conveyed by the cartoons, and not their actual effects on the audience. Therefore, a further phase of this research might verify the efficiency of the campaign for the last edition of Expo, with particular reference to Foody and his friends. This could be done by surveying people who have viewed the cartoons after having set up various different conditions in order to test the effects of the humorous communication conveyed by Foody and his friends with an appropriate experimental design. Moreover, it can be considered that this campaign has a very wide target audience, so it would be interesting to analyse its communicative effects on different samples from different populations (in statistical terms), dividing groups according to their ages or cultural backgrounds. Even though our analysis does not represent an attempt to evaluate the efficacy of the Expo advertising campaign, as a first step we aimed to analyse the role of humour in enriching this particular anthropomorphic mascot and to highlight the main functions that humorous communication can have in a context such as this.

References

1 BIE Paris. (2015a), A short history of expos. Available from BIE Paris: http://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/expos/past-expos/past-expos-a-short-history-of-expos [Accessed 14 January 2016].

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Expo Milano 2015. (2015a), The theme. Available from Expo Milano 2015: http://www.expo2015.org/archive/en/learn-more/the-theme.html [Accessed 17 January 2016].

5 BIE Paris. (2015b), Feeding the planet, energy for life. Available from BIE Paris: http://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/expos/past-expos/expo-milano-2015/theme-feeding-the-planet-energy-for-life [Accessed 14 January 2016].

p.128

6 Locatelli, G., & Mancini, M. (2010), Risk management in a mega-project: the Universal EXPO 2015 case, International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, 2(3), 236–253.

7 George, R. (2008), Marketing tourism in South Africa (3rd ed.), Cape Town; New York: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

8 Gregry, J. J., & Swart, M. P. (2013), The moderating effect of biographic variables in the relationship between expo product and expo promotion – HuntEx 2012, Presented at the XXX Pan Pacific Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 3–6 June 2013.

9 Hiller, H. H. (1998), Assessing the impact of mega-events: a linkage model, Current Issues in Tourism, 1(1), 47–57.

10 Hede, A. M., & Kellett, P. (2011), Marketing communications for special events: analysing managerial practice, consumer perceptions and preferences, European Journal of Marketing, 45(6), 987–1004.

11 Close, A. G., Finney, R. Z., Lacey, R. Z., & Sneath, J. Z. (2006), Engaging the consumer through event marketing: linking attendees with the sponsor, community, and brand, Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 420–433.

12 Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003), Consumer–company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies, Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88; Delre, S. A., Jager, W., Bijmolt, T. H. A., & Janssen, M. A. (2007), Targeting and timing promotional activities: an agent-based model for the takeoff of new products, Journal of Business Research, 60(8), 826–835; Holm, O. (2006), Integrated marketing communication: from tactics to strategy, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 11(1), 23–33; Pitta, D. A., Weisgal, M., & Lynagh, P. (2006), Integrating exhibit marketing into integrated marketing communications, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(3), 156–166; Rotfeld, H. J. (2006), Understanding advertising clutter and the real solution to declining audience attention to mass media commercial messages, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(4), 180–181; Sneath, J. Z., Finney, R. Z., & Close, A. G. (2006), An IMC approach to event marketing: the effects of sponsorship and experience on customer attitudes, Journal of Advertising Research, 45(4), 373–397.

13 Expo Milano 2015. (2015b), Rivivi Expo Milano 2015. Available from Expo Milano 2015: http://www.expo2015.org/rivivi-expo/ [Accessed 4 February 2016].

14 Expo Milano 2015. (2015c), Ti presento Foody, Progetto Scuola. Available from Expo Milano 2015: http://www.progettoscuola.expo2015.org/mascotte/ti-presento-foody [Accessed 27 July 2016].

15 Expo Milano 2015. (2015d), The mascot. Available from Expo Milano 2015: http://www.expo2015.org/archive/en/learn-more/the-theme/the-mascot.html [Accessed 17 January 2016].

16 Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015a), With Guagliò the Garlic, there’s always something new cooking [screenshot]. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nmJUzubq4IA [Accessed 21 March 2016]. Kindly licensed by Expo 2015 S.p.a. and The Walt Disney Company Italia S.r.l.

17 Wikimedia Commons. (2007), Rudolf II as Vertumnus. Available from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arcimboldovertemnus.jpeg [Accessed 21 March 2016].

18 Patterson, A., Khogeer, Y., & Hodgson, J. (2013), How to create an influential anthropomorphic mascot: literary musings on marketing, make-believe, and meerkats, Journal of Marketing Management, 29(1–2), 69–85.

19 Connell, P. M. (2013), The role of baseline physical similarity to humans in consumer responses to anthropomorphic animal images, Psychology & Marketing, 30(6), 461–469.

20 Malik, G., & Guptha, A. (2014), Impact of celebrity endorsements and brand mascots on consumer buying behavior, Journal of Global Marketing, 27(2), 128–143.

21 Stone, S. M. (2014), The psychology of using animals in advertising, in Hawaii University International Conferences Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences, Honolulu, 3–6 January 2004.

22 Hayden, D., & Dills, B. (2015), Smokey the Bear should come to the beach: using mascot to promote marine conservation, Social Marketing Quarterly, 21(1), 3–13.

p.129

23 Aaker, D. A. (1991), Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name, New York: Free Press; Aggarwal, P., & McGill, A. L. (2007), Is that car smiling at me? Schema congruity as a basis for evaluating anthropomorphized products, Journal of Consumer Research, 34(4), 468–479; Delbaere, M., McQuarrie, E. F., & Phillips, B. (2011), Personification in advertising, Journal of Advertising, 40(1), 121–130; Fournier, S. (1998), Consumers and their brands: developing relationship theory in consumer research, Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 343–373.

24 Cayla, J. (2013), Brand mascots as organisational totems, Journal of Marketing Management, 29(1–2), 86–104.

25 Harquail, C. V. (2008), Practice and identity: using a brand symbol to construct organizational identity, in Lerpold, L., Ravasi, D., von Rekom, J., & Soenen, G. (Eds.), Organizational identity in practice, 135–150. London: Routledge.

26 Schultz, E. J. (2012), Mascots are brands’ best social-media accessories, Advertising Age, 83(13), 2–25.

27 Bhattacharya & Sen, op. cit.

28 Aaker, D. A. (2009), Managing brand equity, US, New York: Simon & Schuster; Delbaere et al., op. cit.

29 Cayla, op. cit.

30 Mithen, S., & Boyer, P. (1996), Anthropomorphism and the evolution of cognition, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 2(4), 717–721.

31 Boyer, P. (1996), What makes anthropomorphism natural: intuitive ontology and cultural representations, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 2(1), 83–97.

32 Fournier, op. cit.

33 Connell, op. cit.

34 Ibid.

35 Shanghai China. (2010), Shio. Available from Information Office of Shanghai Municipality: http://en.shio.gov.cn/expo.html [Accessed 17 January 2016].

36 Expo Aichi 2005. (2005), Official mascots / Official music. Available from Expo 2005 Aichi, Japan: http://www.expo2005.or.jp/en/whatexpo/mascot.html [Accessed 17 January 2016].

37 Expo Milano 2015. (2015e), Foody and friends, Progetto Scuola. Available from Expo Milano 2015: http://www.progettoscuola.expo2015.org/docenti/video-gallery/foody-friends [Accessed 17 January 2016].

38 Expo Milano 2015, op. cit.

39 Patterson, Khogeer, & Hodgson, op. cit.

40 Weinberger, M. G., & Gulas, C. S. (1992), The impact of humor in advertising: a review, Journal of Advertising, 21(4), 35–59.

41 Terrion, J. L., & Ashforth, B. E. (2002), From “I” to “we”: the role of putdown humor and identity in the development of a temporary group, Human Relations, 55(1), 55–88.

42 Drew, P. (1987), Po-faced receipts of teases, Linguistics, 25(1), 219–253; Shapiro, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Kessler, J. W. (1991), A three-component model of children’s teasing: aggression, humor, and ambiguity, Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 10(4), 459–472.

43 Apter, M. J. (1982), The experience of motivation: the theory of psychological reversals, UK, London: Academic Press.

44 Dynel, M. (2009), Humorous garden paths, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; Martin, R. A. (2007), The psychology of humor: an integrative approach, Burlington, MA: Elsevier; Ritchie, G. (2004), The linguistic analysis of jokes, London: Routledge; Canestrari, C., & Bianchi, I. (2013), From perception of contrarieties to humorous incongruities, in Dynel, M. (Ed.), Developments in linguistic humour theory, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 3–24; Canestrari, C., Dionigi, A., & Zuczkowski, A. (2014), Humor understanding and knowledge, Language & Dialogue, 4(2), 261–283; Forabosco, G. (1992), Cognitive aspects of the humor process: the concept of incongruity, Humor. International Journal of Humor Research, 5(1/2), 45–68.

45 McGhee, P. E. (1979), Humor: its origin and development, San Francisco, CA: Freeman.

46 Ibid.

p.130

47 Attardo, S., & Raskin, V. (1991), Script theory revis(it)ed: joke similarity and joke representation model, Humor. International Journal of Humor Research, 4(3/4), 293–347; Giora, R. (2003), On our mind: salience, context, and figurative language, New York: Oxford University Press; Brône, G., Feyaerts, K., & Veale, T. (2006), Introduction: cognitive linguistic approaches to humor, Humor. International Journal of Humor Research, 19(3), 203–228.

48 Maier, N. R. F. (1932), A Gestalt theory of humour, British Journal of Psychology, 23, 69–74; Canestrari, C., & Bianchi, I. (2012), Perception of contrariety in jokes, Discourse Processes, 49(7), 539–564.

49 Deckers, L. (1993), On the validity of weight-judging paradigm for the study of humor, Humor. International Journal of Humor Research, 6(1), 43–56; Nerhardt, G. (1970), Humor and inclination to laugh: emotional reactions to stimuli of different divergence from a range of expectancy, Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 11, 185–195; Nerhardt, G. (1976), Incongruity and funniness: towards a new descriptive model, in Chapman, A. J., & Foot, H. C. (Eds.), Humour and laughter: theory, research and applications, London: Wiley, 55–62.

50 Canestrari & Bianchi, op. cit.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

53 Ritchie, G. (1999), Developing incongruity-resolution theory, in Proceedings of the AISB 99 Symposium on Creative Language in Edinburgh, Scotland, 6–9 April 1999, 78–85.

54 Koestler, A. (1964), The act of creation, London: Hutchinson.

55 Attardo, S. (1997), The semantic foundations of cognitive theories of humor, Humor. International Journal of Humor Research, 10(4), 395–420.

56 Giora, R. (1991), On the cognitive aspects of the joke, Journal of Pragmatics, 16, 465–485.

57 LeVine, P., & Scollon, R. (2004), Discourse and technology: multimodal discourse analysis, Washington DC: Georgetown University Press; O’Halloran, K. (2004), Multimodal discourse analysis: systemic functional perspectives, London: Continuum; Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2001), Multimodal discourse: the modes and media of contemporary communication, Oxford, UK: Oxford, University Press.

58 Davis, B., & Mason, P. (2004), Trying on voices: using questions to establish authority, identity, and recipient design in electronic discourse, in LeVine, P., & Scollon, R. (Eds.), Discourse and technology: multimodal discourse analysis, Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 47–58; Jewitt, C. (2004), Multimodality and new communication technologies, in LeVine, P., & Scollon, R. (Eds.), Discourse and technology: multimodal discourse analysis, Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 184–195; Jones, R. H. (2004), The problem of context in computer-mediated communication, in LeVine, P., & Scollon, R. (Eds.), Discourse and technology: multimodal discourse analysis, Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 20–33.

59 Erickson, F. (2004), Origins: a brief and intellectual technological history of the emergence of multimodal discourse analysis, in LeVine, P., & Scollon, R. (Eds.), Discourse and technology: multimodal discourse analysis, Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 196–207.

60 Van Leeuwen, T. (2012), The reasons why linguists should pay attention to visual communication, in LeVine, P., & Scollon, R. (Eds.), Discourse and technology: multimodal discourse analysis, Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 7–19.

61 Erickson, op. cit.

62 Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015b), Arabella, la dolce acidella. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2OkxiF986Y [Accessed 5 March 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015c), Chicca, la super melagrana. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kVjB04PGX2s [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015d), Con Guagliò non è la solita minestra. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxOY0vMAflQ [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015e), Gury, un talento natural. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LEvE_Q679Y [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015f), Josephine, la banana matura. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=owGSrH96hH0 [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015g), Manghy, il bello di Bollywood. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vdSheRMbUu4 [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015h), Max Mais, il musicista pop-corn. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TBl5Y1w-T2E [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015i), Piera, fiera del fisico a pera. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ohvVdhNSMro [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015j), Pomina, l’attrice acerba. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UrjLeFPlGVI [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015k), Rap Brothers, fratelli & rapanelli. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uHiaN-t1UE [Accessed 7 October 2016]; Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair. (2015l), Rodolfo, il vero fico. Available from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HEBFkb2miYQ [Accessed 7 October 2016].

p.131

63 Expo Milano 2015 World’s Fair, op.cit. Kindly licensed by Expo 2015 S.p.a. and The Walt Disney Company Italia S.r.l.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Bhattacharya & Sen, op. cit.

67 Malik, G., & Guptha, A. (2014), Impact of celebrity endorsements and brand mascots on consumer buying behavior, Journal of Global Marketing, 27(2), 128–143.

68 Meyer, J. C. (2000), Humor as a double-edged sword: four functions of humor in communication, Communication Theory, 10(3), 310–331.

69 Ibid.

70 Goldstein, J. H. (1976), Theoretical notes on humor, Journal of Communication, 26(3), 104–112.

71 Goldstein, op. cit.; Patterson et al., op. cit.

72 Martin, R. (2003), Sense of humor, in Lopez, S. J., & Snyder, C. R. (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: a handbook of models and measures, Washington DC: American Psychological Association; Sprecher, S., & Regan, P. C. (2002), Liking some things (in some people) more than others: partner preferences in romantic relationships and friendships, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(4), 463–481.

73 Patterson et al., op. cit.

74 Kellaris, J. J., & Cline, T. W. (2008), Humor and ad memorability: on the contributions of humor expectancy, relevancy, and need for humor, Psychology & Marketing, 24, 497–509.

75 Narwal, P., & Kumar, A. (2011), A study on challenges and impact of advertisement for impulse goods, Research Journal of Social Science & Management, 6, 25–40.