p.204

4.5 Does verbal irony have a place in the workplace?

Roger J. Kreuz

Introduction

After one’s family, the workplace stands at the center of most adults’ lives. We spend half our waking hours each day in the presence of others with whom we share a tangle of social relationships. Just as one cannot choose one’s family, most of us have no control over who our supervisors or our coworkers are. Nonetheless, we are expected to maintain harmonious relationships with others, even with those who may be competitors for advancement or resources. In other cases, we attempt to foster closer relationships with coworkers we happen to like. It is also the case that relationships between employees can change as their institutional roles change. The workplace, therefore, can be characterized as a complex social milieu in which actors pursue a multitude of diverse agendas, and even innocent or well-meaning statements may be scrutinized by their recipients for subtext or multiple messages. These issues are exacerbated in computer-mediated communication (e.g., e-mail and social media), which typically lacks the contextual cues of face-to-face interaction. Given all of this, it is easy to see how workplace communication can lead to miscommunication.

Problems in communication often revolve around the expression of emotion. The expression of strong emotion via language is problematic in many cultures, and the direct expression of negative emotions is often taboo. As a result, hostility or anger may be expressed indirectly, but this indirectness also creates ambiguity about a message’s intent. Different recipients may perceive the same message as humorous or as threatening, depending on their relationship with the speaker or author, and the context in which the message is delivered and received.

The importance of emotions and emotional expression in the workplace were relatively neglected topics of research until the mid-1990s.1 Since that time, however, researchers have begun to explore the communication of emotion via language in a variety of contexts, including in the workplace.

Some terminology

Information about emotional states is often conveyed indirectly, by using so-called nonliteral language. If we were to imagine a very angry coworker, we could use a variety of such forms to describe her, her thoughts, and her behaviors. This could include the use of idioms (“she flipped her lid”), metaphors (“she was a volcano”), similes (“her anger was like a tsunami”), exaggeration (“she wanted to kill someone”), as well as exaggeration’s polar opposite, understatement (“she was slightly vexed”).

p.205

The communication of negative emotion is also frequently accomplished through the use of verbal irony, in which a speaker says the opposite of what she means. An example would be a coworker remarking “Gee, what lovely weather we’re having!” during a heavy downpour. Most theorists characterize verbal irony as conceptually distinct from other phenomena also referred to as irony. Examples include dramatic irony, in which an audience is aware of something that an actor is ignorant of,2 and situational irony, which is the juxtaposition of two incongruous things (e.g., the fire station that catches fire).3

Verbal irony’s close cousin is sarcasm, and the dividing line between these two forms is not entirely unclear. Different researchers define and use the two terms differently, and they are frequently conflated in nonacademic usage, particularly in the United States.4 To muddy the waters further, some have argued that sarcasm does not necessarily entail irony; from this perspective, sarcasm is synonymous with any disparaging remark that involves some element of humor.5 When a distinction is made, however, sarcasm is typically viewed as a subtype of verbal irony, and as a form of language that has a clear victim or target (as in “The boss has made another brilliant business decision!” when he has not).6

It should therefore come as no surprise to learn that the relations between the terms “humor,” “irony,” and “sarcasm” are also ill-defined. Many conventional ironic statements (such as muttering “Oh, that’s just great!” when dropping one’s car keys into a puddle) aren’t humorous at all.7 A barbed sarcastic remark is not very funny either—if you happen to be on the receiving end of such a statement. However, many ironic and sarcastic utterances are perceived as clever or witty, and this may be a principal reason for why this form of language is used so frequently.8

For the purposes of this chapter, I will generally employ the terms “verbal irony” or “irony,” since they are the broadest and most inclusive. However, I will use “sarcasm” if that was the term employed by the original theorists and researchers whose work is under discussion.

Varieties of verbal irony

Verbal irony is often employed to highlight the difference between one’s expectations and a particular outcome. For example, we hope that people will be helpful, that our enterprises will meet with success, and that the weather will be pleasant. This bias toward the positive, dubbed the “Pollyanna principle,”9 can be thought of as reflecting implicit cultural norms. When reality doesn’t align with our hopes, we can ironically echo these cultural expectations. If a coworker agrees to assist you with something and then fails to appear at the appointed time, you might greet him with “Gee, thanks for all help!” at your next meeting. (Since your coworker is the clear target of the remark, this would be an example of sarcasm.)

The idea of an implicit or explicit echo has been an important component of many theories of verbal irony. In echoic mention theory,10 for example, the echo is of a thought, attitude, or cultural norm that is attributed to a person or to a group. In echoic reminder theory,11 the ironic utterance reminds the addressee of the thought, attitude, or norm being echoed. In both cases, the critical idea is that the addressee is forced to consider the gap that exists between what was said and the current state of affairs, which should allow her to arrive at the speaker’s intended meaning. In a later refinement of this approach, referred to as Allusional Pretense Theory,12 it was proposed that pragmatic insincerity is also a key feature of ironic language. That is, it must be clear to the addressee that the speaker has violated a pragmatic norm of literal language use (such as the expectation that people say things which are true). However, the necessity of pragmatic insincerity has also been called into question in later research.13

p.206

If verbal irony is characterized by a mismatch between expectations and outcome, then a negative evaluation of a positive outcome should, in theory, work just as well. In practice, however, this isn’t the case. A remark about “lovely weather” during a heavy downpour (a positive evaluation of a negative outcome) is an example of what has been labeled canonical irony, and such statements are quickly and reliably interpreted as nonliteral.14 Non-canonical ironic statements, by contrast, are negative evaluations of positive outcomes. Since there is, once again, a mismatch between a remark and reality, it might be expected that such statements would also be interpreted unambiguously.

Interestingly, however, this isn’t what happens. Imagine that one’s boss says “Gee, what terrible weather we’re having!” on a pleasant, sunny day. This would seem odd, at least in part because it is a violation of the Pollyanna principle described above. Participants in comprehension experiments take longer to read such statements, and aren’t as certain that such remarks are intended to be ironic.15 In fact, when asked why a person might say such a thing, research participants offer up a host of potential reasons: maybe the speaker is in a bad mood, or perhaps they’re mocking some earlier, incorrect prediction about stormy weather.16 What they are less likely to do is to interpret the statement as implying its opposite, and to understand it as an ironic acknowledgment of a pleasant day.

As we know all too well, ironic statements can and do go awry. To be understood as intended, they require knowledge of one’s conversational partner, as well as the correct interpretation of linguistic and paralinguistic cues, such as the use of exaggeration and a certain tone of voice.17 However, some of the problematic issues in the use of verbal irony may have as much to do with the acceptance of the ironist’s attitude as with the propositions themselves.18 In addition, there may also be differing pragmatic standards with regard to the use of verbal irony, even within the same culture. It has been demonstrated, for example, that college students in a northern US sample perceived sarcasm as more humorous than critical, but this was not the case for participants attending a university in the southern US. Perhaps as a consequence, the southern participants spontaneously employed sarcasm to a lesser degree in a free response task designed to elicit such language.19

In trying to make sense of the multitude of theoretical perspectives that have been advanced, some researchers have highlighted criticism as an essential component of ironic language.20 A crucial issue, however, may be whom this criticism is directed towards—the hearer or some other party. Other theorists have attempted to bring verbal irony under the umbrella of Politeness Theory.21 In this theoretical approach, it is proposed that individuals minimize the impact of face-threatening acts (like making requests of others) by going “off record.” That is, instead of directly asking for something, which might be perceived as face threatening, the requester can instead make a related statement, and leave it to the listener to infer the speaker’s intent, as in, “Say, do you happen to have any change?” in place of directly asking to borrow some money. Several studies have shown that people automatically interpret such statements according to their off-record intent, and not as literal questions about knowledge or ability.22

One issue with Politeness Theory, however, is that a clean division between on- and off-record strategies is problematic: some statements seem to contain a mixture of both.23 This can occur, for example, when someone makes a prediction that is proven incorrect. Imagine a nervous employee who predicts to a friend that his presentation will not be well received. If, in fact, the presentation goes well, his friend could mockingly echo the prediction, which would be a combination of praise (you did well) and criticism (you worry too much). The on-record compliment is tempered by the off-record critique, and such ironic compliments are perceived as more muted than literal compliments.24

p.207

Later research, however, has called this muting function into question. Far from diluting condemnation, ironic criticism can actually enhance its critical impact, at least in some circumstances.25 However, this negativity depends very much on one’s perspective. It has also been reported that participants who take the point of view of an aggressor find sarcastic comments to be less aggressive, and more humorous, than when they are assigned the point of view of the being the target of such statements. As the authors of the study conclude, the effects of sarcasm are truly in the eye of the beholder, and that “the same comments are understood quite differently when one utters a barb than when one is stung by it” (p. 232).26 Finally, more recent work suggests that ironic criticism can be simultaneously more mocking and more polite.27 Clearly, the pragmatic functions of ironic criticism are complex and deserving of additional study.

Verbal irony in close relationships

Many of the negative concepts we associate with verbal irony and sarcasm, such as hostility and belittlement, do not seem to apply when such language is used by friends and intimate partners. In an analysis of conversations between college students and their friends, it was found that ironic statements occurred frequently, at a rate of about one in twelve conversational turns,28 which is comparable to an estimate made by another researcher in a different discourse context.29 In addition, a positive correlation has been found between the likelihood that two people will use sarcasm and the perceived closeness of their relationship.30 Clearly, ironic remarks made by friends are fulfilling very different discourse goals than those made by adversaries.

To speak nonliterally is to run the risk of being misunderstood. But that risk will be minimized if the speaker and hearer share sufficient common ground. In such a case, the hearer will be able to see through the apparent ruse, and interpret the remark as meaning something different from what was literally said. Common ground has been defined as including factors like shared community membership (be it a family, team, profession, religion, or culture), or the same physical environment.31 A shared environment explains why a remark about gorgeous weather on a rainy day will be interpreted as ironic, since both parties are experiencing the same foul weather, and the mismatch between statement and reality is obvious.

But what if shared community membership is unknown, or if the speaker wants to refer to something that is not physically present? In such cases, people might employ a heuristic of inferability: a rough calculation of whether a hearer is likely to interpret a nonliteral remark correctly.32 If inferability is high, as it would be among intimates, then would-be ironists should feel free to make completely outrageous statements, secure in the knowledge they will not be interpreted literally. And in such cases, the need to use facial, gestural, or intonation cues to signal ironic intent drops away as well. Among intimates, in fact, it is not unusual for ironic statements to be made in a totally deadpan way.33

However, when conversing with a stranger, the would-be ironist might decide to play it safe, and to speak in a very literal way. Like all rules of thumb, however, this heuristic is not infallible, and a given speaker may over- or underestimate the common ground that she shares with her addressee. This is likely to occur in environments like the workplace, in which employees share the common ground provided by their occupations, but possibly little else. Many workplaces are quite diverse, and similar beliefs and attitudes concerning politics, sexuality, or religion, to name just a few, are unlikely to be shared by all.

p.208

In fact, the use of verbal irony or sarcasm can function as a signal of allegiance or even as a marker of intimacy. In this way, such statements become a signifier that the addressee is part of an in-group. This idea forms the basis of Pretense Theory.34 According to this formulation, the ironic speaker is pretending to be an ignorant and injudicious person, speaking to a credulous audience. The addressee, however, is able to see through this ruse, and understands the real meaning of the speaker. Viewed in this way, the speaker invites the addressee to become a member of an exclusive club: one of the few who possess the requisite knowledge to understand the remark as intended.

This idea of exclusivity has found some empirical support.35 A study was designed to test the idea that such language may promote and be emblematic of solidary relationships (those in which the participants have a shared past, a collective identity, and interact as equals36). The researchers found, for example, that ironic statements made to solidary recipients were perceived as more humorous and playful than those made to nonsolidary addressees.

The flip side of intimacy, of course, is exclusion. So while verbal irony may foster intimacy between the speaker and addressee, by definition there will be others (e.g., side participants, bystanders, and overhearers) for whom such remarks will function in an exclusionary way. In addition to creating and promoting an in-group, the ironist, intentionally or not, also creates an out-group: those who fail to understand the remark due to a lack of context or familiarity with the speaker. And if someone isn’t in on a joke, they may start to worry that they are the unwitting target of such remarks.

To take things a step further, we can consider cases in which verbal irony is used to express hostility, albeit indirectly. This type of sarcastic speech is characteristic of passive-aggressive behavior,37 since it allows the ironist to protest that he or she was “only teasing” or “just kidding.” In this way, the wielder of such statements can turn the tables and ask why the addressee can’t take a joke. Unfortunately, the line that separates good-natured teasing from subtle forms of hostility is highly variable and subjective, especially in the workplace,38 and the lack of clarity about an ironist’s true motivation can make it very difficult to determine his intent. To complicate matters further, some have argued that men and women use language in very different ways,39 so ironic banter directed at a female employee by a male may be perceived as threatening, and possibly even as harassment. In 2011, a supervisor in Queensland had her employment terminated when she was accused of bullying and harassing another employee over a two-year period. As an example of hostile behavior, it was reported that the supervisor told the worker that she “deserved the employee-of-the-year award” while using a sarcastic tone of voice. In this case, however, the supervisor appealed the decision, and Fair Work Australia ruled in her favor, noting that the supervisor’s “unprofessional and inappropriate” behavior did not rise to the level of harassment.40 Would the outcome have been different if the supervisor of the female employee had been a man instead?

Verbal irony has traditionally been studied in the laboratory in the speech of dyads or small groups.41 Undoubtedly, however, this form of language serves important communicative functions in larger groups as well,42 and it is reasonable to assume that similar factors affect verbal irony use within larger social contexts, such as within a business or corporation.

p.209

Verbal irony in the workplace

The general orientation of the workplace literature has been to view verbal irony, and sarcasm in particular, in a relatively negative light. Some have characterized it almost exclusively as a way of expressing hostility.43 Furthermore, many online sources that purport to dispense business advice are full of warnings about this form of language. One such webpage begins with the following: “Sarcasm is used far too often by people . . . it weakens teamwork and reduces morale.”44 Another equates the use of sarcasm with being a “smart mouth person,” the type responsible for the undermining of others and the lowering of productivity. The author goes on to discuss the pros and cons of confronting or ignoring such disruptive individuals.45 A third online source recommends taking a strong stand against workplace sarcasm, characterizing it as “humor at its worst.”46

As we have seen, this one-dimensional view of verbal irony is problematic at best. Just as a screwdriver can be used as a tool or as a weapon, verbal irony can be employed to fulfill a variety of discourse goals, including the positive goals of expressing humor47 and showing solidarity with one’s conversational partner.48 Verbal irony, therefore, should not be conceptualized in positive or negative terms, but rather as a means of achieving multiple communicative ends.49 Some of these communicative ends, such as expressing frustration in a socially acceptable way, would be difficult, if not impossible, to convey via literal language.50

Some researchers have argued that previous theoretical accounts of verbal irony fail to take into account the more confrontational aspects of such language.51 And it is in environments like the workplace that humor and irony can take on more of a hard edge. Why might this be? One major difference is that, in comparison to relations with friends and intimates, the workplace involves a hierarchy. In fact, most workplaces are largely defined by the existence of asymmetrical power relationships. Subordinates can find it difficult to directly contradict or to criticize their superiors, and the use of humor and irony provide a more socially acceptable way to carry out such face-threatening acts. Importantly, however, the reverse is also true: superiors have to cajole and occasionally reprimand their subordinates, and they need to do so in ways that won’t create conflict, or injure a worker’s pride or morale.

One study of ironic humor in the workplace, specifically involving the statements of senior managers during staff meetings, revealed that such utterances were employed to discuss serious issues in a less threatening and more playful way. For example, after a series of discouraging reports about attempts to reduce inventory, the general manager of the firm commented, “Right, other than that, everything went great!” (p. 280).52 This remark led to an outburst of laughter from the other managers. The statement was interpreted as an attempt to neutralize the negative emotional response of the team to some unwelcome news. The use of contradiction to create humor reveals yet another way that such statements allow their speakers to satisfy multiple discourse goals. A literal acknowledgment of the inventory reduction problems would have been damaging to the morale of the management team. By responding ironically, the general manager acknowledged the seriousness of the issue, but also signaled confidence that the problems could be overcome.

A recent and intriguing report found that the use of sarcasm can lead to higher perceptions of conflict, but also to greater levels of creativity.53 In one experiment, online subjects participated in a simulated conversation task, and were exposed to either sarcastic or sincere statements that had been generated earlier by a different set of participants. Next, creativity was assessed by having the subjects complete a widely used measure of creativity, the Remote Association Task (RAT; e.g., thinking of the word “pool” as the common element linking “hall,” “car,” and “swimming”). Afterwards, the participants completed scales that assessed their perception of conflict. Not surprisingly, the subjects who had been repeatedly exposed to sarcasm reported higher perceived conflict than those in the sincere condition, but they also solved significantly more RAT items than participants in the sincere condition, or in a control condition.

p.210

A second study used a different sarcasm induction technique: participants were asked to recall a personally relevant experience of sarcasm, or their last conversation with someone who asked them for directions (a control condition). The measure of creativity was also different: subjects attempted to solve the Duncker Candle Problem (participants are asked to attach a candle to a wall, which requires overcoming functional fixedness about using a tack box as a candle stand). Once again, the subjects who had thought about sarcasm reported experiencing more conflict, but they were also more likely to solve the Candle Problem than the control participants.

In a final experiment, participants were asked to imagine that the same sarcastic statements used in an earlier study were being spoken by someone they greatly trusted, or by someone they distrusted. Participants in the distrust condition reported greater perceived conflict, but those in the trust condition did not. Significantly, however, both groups performed better on yet another measure of creativity than control participants who imagined non-sarcastic conversations. (In this case, the participants were asked to solve the Olive in a Glass problem, which involves overcoming assumptions about the position or orientation of a glass in order to move an olive.)

Taken as a whole, the authors interpret their results as suggesting that sarcasm may be a catalyst for abstract thinking, and that such thinking is an important antecedent of creative behavior. To quote the authors, sarcasm “helps people think creatively even as they seethe in conflict.”54 However, their results also suggest that the beneficial effects of sarcasm may only accrue to members of a team who trust each other. The finding that sarcasm can boost creativity without increasing conflict has obvious implications for the workplace.

Verbal irony online

Finally, some of the issues raised earlier become even more problematic when we consider computer-mediated communication, such as via e-mail, text messaging, tweets, and Facebook postings. These impoverished communication channels lack the paralinguistic cues, such as intonation and gesture, that normally aid in the detection of nonliteral intent in face-to-face communication. The example of a boss making a brilliant business decision mentioned earlier takes on a clear nonliteral meaning if the speaker accompanies her statement with heavy stress and a slow speaking rate, or by rolling her eyes. Not surprisingly, therefore, recognizing humor and irony in social media has been described as especially problematic.55

Although most of us believe that our e-mails and status updates are clear enough, we have all been on the receiving end of online messages in which the actual intent of the sender was far from transparent. A series of experiments has demonstrated that a pervasive egocentric bias exists with regard to detecting sarcasm in e-mail messages.56 It appears that people are largely unable to imagine that their own messages, in which the humorous or sarcastic intent seems clear enough, might be ambiguous to someone else. In fact, one study found that participants were more likely to use irony in computer-mediated communication than they were conversing face to face.57

p.211

In an attempt to cope with the challenges of online communication, language users have created new conventions, such as emoticons and emoji. Although they can serve a variety of purposes, emoticons are commonly used to mark nonliteral intent.58 An early study of how these typographic conventions are employed in e-mail found that the “wink” emoticon ; - ) was most strongly associated with sarcasm.59 However, these researchers also reported that a wink plus a positive verbal message was not perceived as more sarcastic than the same message accompanied by a smile : - ) , a frown : - ( , or when paired with no emoticon at all. The study found that emoticons had a relatively small effect on the communication of emotion in general, and sarcasm in particular. It is worth noting, however, that a later experiment, in which secondary school students were the participants, found that emoticons did strengthen the intensity of a message.60 This suggests that the use of, and pragmatic agreement about, such conventions may have increased over time.

Researchers have also explored whether nonliteral language is stereotypic enough to be identified through the use of specific features. It has been suggested, for example, that ironic language might be identified by the use of extreme exaggeration, such as via collocations of adverbs and extreme positive adjectives (e.g., “just delightful” or “absolutely incredible”).61 These researchers demonstrated that participants perceived nonliteral statements that contained clear exaggeration to be more ironic than similar statements that were not as extreme (e.g., “I’ll never be able to repay you for your help!” versus “Thanks for helping me out”).

One issue in analyzing the nonliteral language that appears in texts is the difficulty of determining whether a given statement was originally intended as ironic or sarcastic. Fortunately, the hash tags used in social media, such as “#sarcasm,” allow researchers to unambiguously determine the intentions of the author. One team of researchers studied sarcastic posts to Twitter, and found that a variety of factors distinguished them from tweets expressing positive or negative sentiment. Specifically, they found that textual factors (like the use of punctuation) and pragmatic dimensions (such as whether the tweet was directed at another person) allowed their machine classifier to perform about as well as human raters.62

A different group of researchers focused on the use of word-level cues in sarcasm, such as interjections (such as “gee,” “gosh,” or “well”) and positive affect terms (which would be indicative of canonical irony). Once again, the model performed almost as well as human classifiers.63 It should be noted, however, that even humans, when asked whether a tweet expressed or did not express sarcasm, were correct only about 70% of the time. Although such performance is better than chance, it does suggest that misinterpretations are fairly common. The impoverished context, imposed by the 140-character limit of this micro-blogging service, makes it challenging to determine sarcastic intent—for humans and machines alike.

Unfortunately, online communication has also created the potential for cyberbullying in the workplace. However, a survey administered to workers in Australia suggests that it may not be as prevalent as cyberbullying among other groups, such as children, 24% of whom report having been cyberbullied at some point.64 Thirty-four percent of the adult survey respondents reported having been bullied face to face in the workplace, while only 11% reported having been cyberbullied. Specifically, just 3% of those bullied face to face reported experiencing “excessive teasing and sarcasm.” And none of those who reported being cyberbullied cited this particular behavior.65

p.212

Conclusions

Clearly, the workplace is an environment in which verbal irony can function as a double-edged sword, cutting more than one way.66 On the one hand, the use of such language can make people feel excluded or less valued. It can distance speakers from their addressees.67 Irony and sarcasm can also be misinterpreted, particularly in online communication. And like any other form of language, it can be used for ill and not just for good.

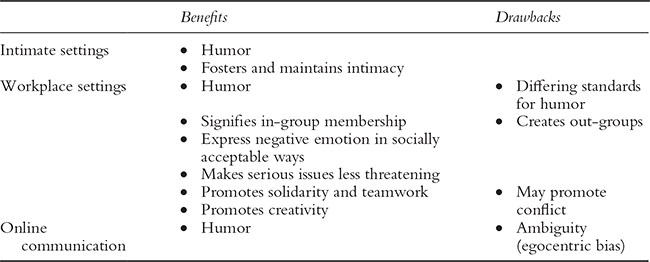

However, it is also true that verbal irony can be used to foster and maintain intimacy. It can promote solidarity and a sense of teamwork. It can allow people to express negative emotions in a socially acceptable way, which is particularly helpful when a differential power relationship exists. Ironic statements are also associated with humor, and with being perceived as witty or clever.68 When used in unexpected ways, as in advertising, it can promote interest and attention.69 It can be employed after the fact to allow people to dissociate themselves from previous problematic statements. And, as we have seen, such language can even foster creativity without creating conflict.70 The review of the literature presented here makes clear that verbal irony does have a place in the workplace after all. Far from being seen only as a conduit for hostility and aggression, under the right circumstances it can be employed in a number of positive ways, as summarized in Table 4.5.1.

Clearly, a great deal has been learned about this complex linguistic form. It would be extremely premature, however, to conclude that all relevant issues have been fully explored and explained. As we have seen, even basic definitional issues concerning use of the terms “irony” and “sarcasm” have not been fully answered. And the generalizability of results from studies of college students (and more recently, online participants) to adults in the workplace is an open question. It is increasingly clear that the use of verbal irony is enmeshed in a host of cognitive, social, and cultural factors, and untangling this complex skein will require patience and ingenuity. Nonetheless, considerable progress has been made, and the increasing amount of research devoted to this intriguing form of language creates some basis for optimism.

Table 4.5.1 The benefits and drawbacks to using verbal irony

p.213

References

1 Ashforth, B. E., & Humphrey, R. H. (1995). Emotion in the workplace: A reappraisal. Human Relations, 48, 97–125.

2 Beckson, K., & Ganz, A. (1989). Literary Terms: A Dictionary (3rd edition). New York: Noonday.

3 Lucariello, J. (1994). Situational irony: A concept of events gone awry. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 123, 129–145.

4 Dynel, M. (2010). Friend or foe? Chandler’s humour from the metarecipient’s perspective, in I. Witczak-Plisiecka (ed.), Pragmatic Perspectives on Language and Linguistics Volume II: Pragmatics of Semantically-restricted Domains. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 175–205; Giora, R., & Attardo, S. (2014). Irony, in S. Attardo (ed.), Encyclopedia of Humor Studies, Volume One. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 397–402; Nunberg, G. (2001). The Way We Talk Now: Commentaries on Language and Culture. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; Wasserman, P. G., & Schober, M. F. (2006). Variability in judgments of spoken irony. Abstracts of the Psychonomic Society, 11, 43.

5 Fowler, H. W. (1965). A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (2nd edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

6 Attardo, S. (2000). Irony as relevant inappropriateness. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 793–826; Kreuz, R. J., & Glucksberg, S. (1989). How to be sarcastic: The echoic reminder theory of verbal irony. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118, 374–386.

7 Norrick, N. R. (2002). Issues in conversational joking. Journal of Pragmatics, 35, 1333–1359.

8 Roberts, R. M., & Kreuz, R. J. (1994). Why do people use figurative language? Psychological Science, 5, 159–163.

9 Matlin, M. W., & Stang, D. J. (1978). The Pollyanna Principle: Selectivity in Language, Memory, and Thought. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Co.

10 Wilson, D., & Sperber, D. (2012). Explaining irony, in D. Wilson & D. Sperber (eds.), Meaning and Relevance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 123–145.

11 Kreuz & Glucksberg, op. cit.

12 Kumon-Nakamura, S., Glucksberg, S., & Brown, M. (1995). How about another piece of pie: The allusional pretense theory of discourse irony. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 124, 3–21.

13 Colston, H. L. (2001). On necessary conditions for verbal irony comprehension. Pragmatics & Cognition, 8, 277–324.

14 Kreuz, R. J., & Link, K. E. (2002). Asymmetries in the perception of verbal irony. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 21, 127–143.

15 Kreuz & Link, op. cit.

16 Kreuz & Glucksberg, op. cit.

17 Caucci, G. M., & Kreuz, R. J. (2012). Social and paralinguistic cues to sarcasm. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 25, 1–22; Kreuz, R. J. (1996). The use of verbal irony: Cues and constraints, in J. S. Mio & A. N. Katz (eds.), Metaphor: Implications and Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 23–38; Kreuz, R. J., & Caucci, G. M. (2009). Social aspects of verbal irony use, in H. Pishwa (ed.), Language and Social Cognition: Expression of the Social Mind. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 325–345.

18 Piskorska, A. (2014). A relevance-theoretic perspective on humorous irony and its failure. Humor, 27, 661–685.

19 Dress, M. L., Kreuz, R. J., Link, K. E., & Caucci, G. M. (2008). Regional variation in the use of sarcasm. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 27, 71–85.

20 Garmendia, J. (2014). The clash: Humor and critical attitude in verbal irony. Humor, 27, 641–659.

21 Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1978/1987). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

22 Gibbs, R. W. Jr. (1983). Do people always process the literal meanings of indirect requests? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 93, 524–533.

23 Alba Juez, L. (1995). Irony and politeness. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 10, 9–16.

24 Dews, S., & Winner, E. (1995). Muting the meaning: A social function of irony. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 10, 3–19.

p.214

25 Colston, H. L. (1997). Salting a wound or sugaring a pill: The pragmatic functions of ironic criticism. Discourse Processes, 23, 25–45.

26 Bowes, A., & Katz, A. (2011). When sarcasm stings. Discourse Processes, 48, 215–236.

27 Boylan, J., & Katz, A. N. (2013). Ironic expression can simultaneously enhance and dilute perception of criticism. Discourse Processes, 50, 187–209.

28 Gibbs, R. W. Jr. (2000). Irony in talk among friends. Metaphor and Symbol, 15, 5–27.

29 Tannen, D. (1984). Conversational Style. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

30 Kreuz, op. cit.

31 Clark, H. H., & Marshall, C. R. (1981). Definite reference and mutual knowledge, in A. K. Joshi, B. Webber, & I. Sag (eds.), Elements of Discourse Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 10–63.

32 Kreuz, op. cit.; Kreuz, R. J. (2000). The production and processing of verbal irony. Metaphor and Symbol, 15, 99–107.

33 Kreuz, R. J., & Roberts, R. M. (1995). Two cues for verbal irony: Hyperbole and the ironic tone of voice. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 10, 21–31.

34 Clark, H. H., & Gerrig, R. J. (1984). On the pretense theory of irony. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 121–126.

35 Pexman, P. M., & Zvaigzne, M. T. (2004). Does irony go better with friends? Metaphor and Symbol, 19, 143–163.

36 Seckman, M., & Couch, C. (1989). Jocularity, sarcasm, and relationships. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 18, 327–344.

37 Vensel, S. R. (2015). Passive-aggressive personality disorder, in L. Sperry (ed.), Mental Health and Mental Disorders: An Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-being. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO/Greenwood Press, 813–816.

38 Norrick, N., & Chiaro, D. (2009). Humor in Interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

39 Tannen, D. (1990). You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. New York: Ballantine Books.

40 Sarcasm is the lowest form of wit . . . but is it bullying? http://www.ihraustralia.com.au/news-and-opinion/sarcasm-is-the-lowest-form-of-wit-but-is-it-bullying (retrieved March 30, 2016).

41 Gibbs, op. cit.

42 Hatch, M. J. (1997). Irony and the social construction of contradiction in the humor of a management team. Organization Science, 8, 275–288.

43 Calabrese, K. R. (2000). Interpersonal conflict and sarcasm in the workplace. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 126, 459–494; Neuman, J. H., & Baron, R. A. (1998). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence concerning specific forms, potential causes, and preferred targets. Journal of Management, 24, 391–419.

44 Clay, C. (n.d.). Workplace communication: What about sarcasm? http://www.deskdemon.com/pages/uk/career/workplacesarcasm?cl=wn-sep-sarcasm (retrieved March 30, 2016).

45 Maleta, Z. (2016). How to deal with a smart mouth person in the workplace. http://work.chron.com/deal-smart-mouth-person-workplace-19093.html (retrieved March 30, 2016).

46 Patterson, K. (2011, March). Confronting workplace sarcasm. http://www.crucialskills.com/2011/03/confronting-workplace-sarcasm/ (retrieved March 30, 2016).

47 Roberts & Kreuz, op. cit.

48 Seckman & Couch, op. cit.

49 Gibbs, R. W. Jr., & Colston, H. L. (2001). The risks and rewards of ironic communication, in G. Anolli, R. Ciceri, & G. Riva (eds.), Say Not to Say: New Perspectives on Miscommunication. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 181–194.

50 Kreuz (2000), op. cit.

51 Holmes, J. K. (2000). Politeness, power and provocation: How humour functions in the workplace. Discourse Studies, 2, 159–185.

52 Hatch, op. cit.

53 Huang, L., Gino, F., & Galinsky, A. D. (2015). The highest form of intelligence: Sarcasm increases creativity for both expressers and recipients. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 131, 162–177.

p.215

54 Huang, op cit., p. 14.

55 Reyes, A., Rosso, P., & Buscaldi, D. (2012). From humor recognition to irony detection: The figurative language of social media. Data & Knowledge Engineering, 74, 1–12.

56 Kruger, J., Eply, N., Parker, J., & Ng, Z. (2005). Egocentrism over e-mail: Can we communicate as well as we think? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 925–936.

57 Hancock, J. T. (2004). Verbal irony use in face-to-face and computer-mediated conversations. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 23, 447–463.

58 Kreuz (1996), op. cit.; Lebduska, L. (2014). Emoji, emoji, what for art thou? Harlot, 12, http://harlotofthearts.org/index.php/harlot/article/view/186/157 (retrieved March 30, 2016).

59 Walther, J. B., & D’Addario, K. D. (2001). The impacts of emoticons on message interpretation in computer-mediated communication. Social Science Computer Review, 19, 324–347.

60 Derks, D., Bos, A. E. R., & von Grumbkow, J. (2008). Emoticons and online message interpretation. Social Science Computer Review, 26, 379–388.

61 Kreuz & Roberts, op. cit.

62 González-Ibáñez, R., Muresan, S., & Wacholder, N. (2011). Identifying sarcasm in Twitter: A closer look, in Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Portland, OR: Association for Computational Linguistics, 581–586.

63 Kovaz, D., Kreuz, R. J., & Riordan, M. A. (2013). Distinguishing sarcasm from literal language: Evidence from books and blogging. Discourse Processes, 50, 598–615.

64 Cyberbullying Research Center. (2013). Cyberbullying research: 2013 update. http://cyberbullying.org/cyberbullying-research-2013-update (retrieved March 30, 2016).

65 Privitera, C., & Campbell, M. A. (2009). Cyberbullying: The new face of workplace bullying. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 12, 395–400.

66 Huang et al., op. cit.

67 Gibbs & Colston, op. cit.

68 Kreuz, R. J., Long, D. L., & Church, M. B. (1991). On being ironic: Pragmatic and mnemonic implications. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 6, 149–162.

69 Gibbs & Colston, op. cit.

70 Huang et al., op. cit.