p.132

3.6 Controversial humor in advertising

Social and cultural implications

Margherita Dore

Introduction

As Nash observes, “[v]irtually any well known forms of words—from the language of politics, of advertising, or journalism, of law and social administration—will serve the requirements of wit”1 (my emphasis). As a matter of fact, witticisms, puns, jokes, satire, parody, etc. are examples of the different forms and guises in which humor can come. Be it scripted (e.g., jokes) or naturally occurring, humor can be used to enhance or challenge interpersonal and social relations.2 It is therefore not surprising that it has been often used in advertising to seek the involvement of the audience while promoting products, services and, consequently, the brand or corporate company that provides them. As Berger explains, humor can create what he calls the “halo effect,” meaning “a feeling of well-being that becomes attached to the products being advertised.”3 Nonetheless, humor in advertisement has often been considered risky, especially due to its potential offensiveness, which can be inadvertent or intentional.4 Moreover, the (non) appreciation of a humorous advert may very well depend on various factors (e.g., personal situation, beliefs, etc.) that often escape the marketers’ control. It is therefore interesting to explore the possible reasons that can lead to a negative response by the receivers of controversial adverts that consciously or unconsciously entail humor. In particular, this paper concentrates on adverts that have been considered offensive by their receivers at the local, national or global level, on the basis of their themes, language and culture-specific references. Considering that such adverts or campaigns set out to address and/or seek the involvement of their target clientele in today’s hyper-politically correct world, the latter’s (unexpected) reaction is worth exploring, as it can be of great interest to advertising companies and marketers alike. Before proceeding with an in-depth analysis of the issue at hand, I will offer a brief overview of humor and how it can be defined for the purposes of this paper.

Humor theories

Humor is a pervasive feature of human life. As Raskin explains, “the ability to appreciate and enjoy humor is universal and shared by all people, even if the kinds of humor they favor differ widely.”5 Humor can indeed be seen as a universal phenomenon, which varies, however, according to different cultures and historical periods. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that scholars in various fields of research have struggled to provide a unified definition.6 Moreover, individual reactions to a potentially humorous stimulus may differ greatly and depend on factors such as personal beliefs and specific situations, as well as an individual’s cultural background. In general, the most obvious and predictable response to humor is laughter. However, Raskin cautiously suggests that laughter is one of the factors that best characterize this aspect of human emotion. Chiaro and Nash maintain that humor and laughter have an implicit relationship,7 while Palmer and Morreall are more inclined to see laughter as an integral part of humor.8 By contrast, Oring talks about laughter and humor as separate phenomena,9 while Attardo points out that, more often than not, humor is incorrectly assimilated to laughter, as the latter may depend on factors such as the use of hallucinogens; it may even serve other purposes (e.g., express embarrassment).10 The different ways humor is perceived deserve a thorough analysis that, however, falls beyond the scope of this chapter. It may suffice to note that these observations confirm the difficulties involved in defining humor and its perception (and/or appreciation). For the purposes of this study, I shall accept Attardo’s broad definition of humor as “whatever a social group defines as such,”11 as it offers sufficiently solid grounds for its analysis. Moreover, I consider laughter as one of the ways human beings may consciously or unconsciously respond to humor.

p.133

From a functional point of view, some scholars have attempted to detect the mechanisms underlying humor and its effect(s) on society by means of different approaches drawn from fields such as anthropology, psychology, philosophy and linguistics.12 Space limitations rule out an extensive review of the substantial body of literature on humor produced to date. It will suffice to mention the most recent approaches developed in the field. Raskin’s analysis of a series of jokes has led him to put forward the Semantic Script Theory of Humor (SSTH) which postulates that to be humorous, a text has to partially or fully oppose and overlap two different scripts, where a script is defined as “a large chunk of semantic information surrounding the word or evoked by it.”13 To this, Attardo adds: “It [a script] is a cognitive structure internalized by the speaker which provides the speaker with information on how things are done, organized, etc.”14 The linguistic ambiguity of a text is due to the fact that the scripts are in opposition and such oppositions are virtually infinite. Attardo sees the SSTH as unable to distinguish between verbal humor (based on language) and referential humor (based on content), which can, however, be subsumed under the umbrella term of Verbally Expressed Humor.15 Moreover, he considers the incongruity-resolution model developed in psychology to be better suited to explaining the interpretative process of a humorous text. According to this model, the interpretation of a joke involves two steps. At first, the receiver interprets the text according to the linguistic cues and the script they activate. Subsequently, the punchline forces the receiver to detect the incongruity and then reinterpret the linguistic cues in the text according to another script, which is in opposition to the one activated previously. This step is called the “resolution” phase.16

Hence, although retaining the SSTH’s main tenets, Attardo (together with Raskin) has developed the General Theory of Verbal Humor (GTVH) to detect the humorous instances in texts longer than self-contained jokes. The GTVH entails six Knowledge Resources (KRs), including the already established features of script opposition. These six KRs are conceived according to a hierarchical structure, at the top of which the script opposition (SO) is found. The KR that follows is called the logical mechanism (LM); it is the parameter that explains how the two scripts are brought together (i.e., by juxtaposition, ground reversal, etc.). As per the incongruity-resolution model mentioned above, the SO is the parameter that reveals the incongruity, while the LM is the parameter that resolves it. The situation (SI) describes the context (e.g., objects, participants, activities, etc.) while the target (TA) defines the “butt” of the joke. The narrative strategy (NS) is responsible for the organization of the text (e.g., a dialog, narrative, figure of speech, etc.). At the bottom, we find the KR called language (LA), which contains the information regarding the verbalization of the text.17 As Tsakona observes, in the case of matching verbal and non-verbal text, the Language KR should be revised to account for both.18

p.134

Since it first appeared, the GTVH has been extensively applied to, and revised to account for, texts longer than jokes, as well as instances of humor in texts other than verbal. For example, drawing on Attardo’s notion of hyperdetermination (i.e., the simultaneous presence of more than one source of humor at the same time19), Tsakona analyzes a series of newspaper cartoons to demonstrate how hyperdetermined humor is the result of the interaction of the language and/or the image. Consequently, cartoons become multilayered compositions made up of one or more script oppositions that are retrieved from our encyclopedic or world knowledge. Since several script oppositions and hyperdetermination can be detected in the same text, this may also explain why people react differently to the same cartoon.20 For her part, Gérin uses the GTVH in conjunction with iconography theories to detect the humor in visual art. In particular, she proposes to redefine the Target KR so that it can distinguish between the butt of the joke that is visually represented and the targeted public or ideal viewer of the image.21 This distinction is crucial for the analysis of adverts that, like visual art, make ample use of visuals, music and sound, alongside spoken and written text.22 Moreover, in the specific case of controversial ads, it stands to reason that in some cases the ideal receiver does not coincide with the real one, which results in mismatching communication between advertisers and consumers. Hence, all these findings and caveats can also be taken into account when applying the GTVH to the analysis of controversial humorous adverts, as well as to the task of understanding the reasons why some people find such ads amusing while others consider them distasteful or even appalling.

Humor in advertising

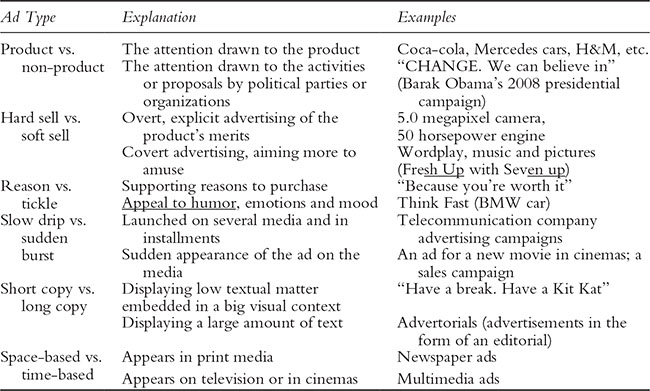

From a general point of view, an advertisement can be described as a message conceived by an advertiser (or advertising company) that is sent to its target receivers. Adverts are conceived by marketers in order to reach a prospective pool of local, national and/or international customers. Simpson and Mayer summarize the categorizations thus far produced for the different types of ads (cf. Table 3.6.1).23

p.135

Table 3.6.1 Summary of advertisement types

As may appear evident, such a categorization is not clear-cut, and some advertisers may use soft-sell strategies in space- and time-base ads. Others may attempt to persuade target customers of the exceptional quality of their product by using long-copy text (e.g., iPhone campaigns). Moreover, ads are categorized according to their inherent features: (1) the headline, with a catchy line that may or may not interact with the visual image; (2) the body copy, which is a longer stretch of text explaining, for instance, the main features of the product; (3) the signature, which is a small picture reporting the trade name of the product (e.g., Unilever); (4) the slogan, which is a memorable phrase accompanying a signature (e.g., I’m lovin’ it, McDonald’s); and (5) the testimonial, normally a famous celebrity endorsing a product (e.g., George Clooney for Nespresso). Interestingly, MacInnis et al. explain how all these ad types have been designed to enhance consumers’ motivation, opportunity and ability (MOA) to process brand information in an advertisement. These variables are respectively described as the desire to process information in adverts, the time devoted to them and the consumers’ skill or proficiency in understanding ads. Humor seems particularly effective in increasing the processing of brand information; yet research has not been able to confirm whether or not its positive effect is due to the surprise value of the brand information in the ad.24 In other words, the humor in an ad may be effective for the online processing of an advert, but it may not result in a tradeoff effect for the brand itself. This point is particularly relevant to the analysis of the examples at hand. Indeed, it could be argued that although controversial humor involves a great deal of surprise, it may not imply a positive customers’ response regarding the product and the brand itself, especially if the humor in the ad is not relevant to the message conveyed.25 In addition, use of humor may produce the so-called “vampire effect,” sucking attention away from the product or message that is advertised.26

The present study will be looking at tickle adverts in particular. As mentioned earlier, such ads, which aim to elicit people’s curiosity and participation,27 are likely to comprise verbal and non-verbal text (i.e., even a written ad on a plain white newspaper page still involves using both verbal and non-verbal elements). In order to provide a systematic analysis of the data under scrutiny, I will refer to Speck’s categorizations of five humorous advert types.28 Speck suggests that four out of five humor types are based on the incongruity-resolution mechanism, which can also be used in conjunction with the arousal–safety mechanism (related to relief and release theories, which see laughing at others as a form of releasing pleasure29), and/or humor disparagement (related to hostility theories, which suggest that humor is created by the speaker’s aggressive attitude towards the object of her/his humorous utterance30). As Speck further explains, comic wit in humorous adverts involves incongruity-resolution alone, whereas satire is based on a combination of incongruity-resolution and disparagement; sentimental comedy involves both arousal–safety and incongruity-resolution, while full comedy involves all three processes. Conversely, the fifth humor type, sentimental humor, entails the arousal–safety process only.31

As Gérin points out, the incongruity-resolution approach mainly focuses on its cognitive mechanism, whereas considering hostility and release theories can shed light on the function of humor.32 Indeed, drawing on Speck, Beard renames sentimental humor as resonant humor and explains that it implies a sort of mild social aggression (e.g., using taboo themes and/or words) that aim to surprise receivers and attract their attention. He also renames sentimental comedy (which produces pleasure when the incongruity is resolved) as resonant wit and points out that, unlike resonant humor, it does not involve offense. Interestingly, Beard has analyzed a series of complaints put forward by New Zealanders against what they deemed to be offensive adverts. The data examined has shown that humor is not the cause of the offense per se; rather it is the theme used in adverts that is potentially offensive, regardless of its humorous or non-humorous content.33 For instance, a humorous advert may be based on the “sex–no-sex” concrete script opposition34 but may not be intentionally offensive; however, if the main theme is “oral sex,” a series of further associations and script oppositions may arise. Thus, one part of the target audience may find it offensive (i.e., some men and women) while others may find it amusing (i.e., other men and women) (cf. the Burger King example below).

p.136

As a matter of fact, humor appreciation may depend on one’s personal disposition and/or contingent factors (cf. for instance, Hatzithomas et al.’s study on the influence of economic conditions on the appreciation of humor in advertising35). Besides, what may determine the (in)appropriateness of humor in general (and in an advert, in this case) is often due to the norms established in a given socio-cultural setting.36 Therefore, the issue of appropriateness becomes paramount when investigating the social and cultural implications that humor in advertising may have. For instance, one famous and much debated example is the 2008 Absolut Vodka advert, which showed a 19th-century map of Mexico with its borders extending further north to include part of the US territory. Despite being aimed at the Mexican public, the ad was picked up by the US media, which roundly criticized this campaign and encouraged US citizens to boycott Absolut Vodka and its products. Eventually, the company was forced to withdraw the ad and publicly apologize.37 Such a drastic action was a clear attempt to ward off business losses in a market that is likely to ensure high returns to Pernod Ricard, the French group that owns the brand.

In the following sections, therefore, the focus will not only be on overtly intentionally offensive humorous adverts, but also on some instances of advertising that were accidentally offensive (or supposedly so), hence failing to obtain a positive response. Be that as it may, it is interesting to notice how the resulting negative emotions and feedback have also led to the receivers getting actively involved, taking action against some of these ads and forcing them to be withdrawn or modified. In other cases, the corporation also issued official apologies, as we shall see below.

Controversial humor in the local and global market

Global corporations’ advertising campaigns are often motivated by two needs: to cut advertising costs and to build a unified image of the brand. Yet cultural barriers can often make such an approach impracticable, and opting for an unlocalized campaign may be detrimental to the message in the ad and the brand itself.38 Nonetheless, even localized campaigns are no guarantee of success, especially if they are based on sensitive or taboo topics. Moreover, the concept of localization in today’s globalized world needs to be challenged, since any advert designed for a given target culture can easily be viewed, shared and commented on over the Internet. In the following subsections, I discuss a series of ads that show how national and multinational corporations or organizations try to exploit humor to generate product appreciation among their prospective buyers. However, other ads will demonstrate how adverts can become inadvertently humorous, thus confirming that the perception and appreciation of such ads are relative concepts. For the sake of clarity, the sections below are divided according to the different types of humor employed. Firstly, I shall discuss some instances of adverts based on verbal humor, in which the image is only used in the background to support the verbal text. I shall then move on to examine instances based on referential humor that are supported by the visual component. This will include adverts based respectively on stereotyped and culture-specific humor. All the examples discussed below are considered to be controversial, given that they have encountered the opposition of their potential receivers.

p.137

Verbal humor

From a purely linguistic point of view, adverts manipulate language and violate the language code in the attempt to extract more meaning, as poetry does. In the case of verbally humorous ads, the different levels of manipulation include spelling and phonology (e.g., “nite” rather than “night,” “donut” instead of “doughnut”), vocabulary (neologisms such as “innervigoration”: in+nerve+vigor+tion), the use of collocations and clichés as well as the exploitation of morphology and syntax (e.g., proliferation of compound nouns and modifiers as in “record-breaking machine”). Along with the playful manipulation of language structures that violate syntax, morphology, etc., advertisers may insert puns and wordplay in headlines, body copy and slogans to promote products and win customers.

Soft and tickle ads rely heavily on such exploitation because they resort to linguistic witticism and can therefore be considered as instances of sentimental comedy/resonant wit, according to Speck’s and Beard’s categorizations discussed above. For instance, the body copy in the Sharp advert “From Sharp minds come Sharp products” is based on words having the same sound, spelling and meaning (i.e. synonymy). The receiver’s pleasure derives from detecting the incongruity-resolution mechanism in the text, which uses the same linguistic item (i.e. sharp) to trigger two different scripts (“intelligent minds” and “IT products”). Conversely, the “Everywear—Burton Menswear” advert is based on homophony (i.e. words having the same sound but different spelling); in this case, the incongruity-resolution mechanisms is based on the activation of the script opposition between “where” and “wear,” and the pleasure stems from the detection of such opposition. Last but not least, London Transport’s advert “Less bread. No jam” deserves mention, as it exploits the spelling similarity of some words with different meanings (i.e. homography). In this case, the “money/no-money” concrete script opposition39 is triggered by the word “bread,” which in this context is slang for “money.” Similarly, the word “jam” activates both the literal and referential meaning of “traffic jam” and the “actual/non-actual” abstract script opposition.40

As I have suggested earlier, some companies and advertising agencies may choose a more sensationalist or provocative approach, which may provoke opposing reactions among the target receivers. From a language-specific standpoint, the 2003 Ryanair (a well-known low-cost airline based in Ireland) “FawKing great offers” advert is a case in point. The campaign was launched a few days before Bonfire Night and advertised flights to the UK in The Daily Telegraph. It played on the homophony between the “F***” word and Guy Fawkes’s name. The latter had famously tried and failed to blow up the House of Parliament in London in 1605, and each year on November 5 people in the UK celebrate the foiling of the Gunpowder Plot with fireworks.41 The potential humor stems exclusively from the verbal text, while the people depicted in the advert merely play a supporting role.42 Clearly, the humor is conveyed when the receiver is able to resolve the incongruity of the first interpretation (the F*** word) with the most relevant and amusing reference to Guy Fawkes’s name.

p.138

From a GTVH standpoint, the SO is “obscene/non-obscene,” while the LM is also “referential ambiguity,”43 the SI is “discount flights offer” and the TA is “Guy Fawkes.” In the data discussed here, the NS is always “advertising”; LA is verbal text only, as the image plays no role in humor production here. Interestingly, the (British) Advertising Standards Authority criticized the advert after receiving complaints from the public who deemed it offensive. Ryanair commented that the ad was “intended to be humorous.”44 As we can see, in this case the proponent of the advert and the receivers disagree on what is offensive or humorous. One possible explanation could be that the customers felt they were the target of the implied reference to the swearword, whereas Ryanair intended Guy Fawkes to be the butt of the joke. Moreover, it could be argued that instead of enjoying the pleasure of resolving the incongruity, these members of the public were disturbed by it. The consumers’ protest also led the ASA to order Ryanair not to run similar campaigns in future.45

The last example I would like to discuss in this section is an instance of a controversial ad that plays on the taboo topic of defecation. The campaign launched in 2011 to promote Sheet Energy Strips, edible strips containing vitamins and nutrients. The billboards offer a clear demonstration of the humor in the three body copies and how the images serve as backdrop to the entailed incongruity.

See the images of the campaign here: http://www.adweek.com/creativity/worst-ad-campaign-year-sheets-energy-strips-134913/ [accessed 05/09/2017].

These billboard adverts are based on the humorous homophonic wordplay between “take a sheet” and “take a shit,” thus implying defecation and all the composing elements of this script. They display three examples of similar body copy (respectively “I take a sheet in the pool,” “I’ve taken a sheet in the library” and “I take a sheet right on the stage”) that should suggest that using these energy strips can help consumers to perform better in different contexts: during physical exercise (swimming), intellectual work (at the library) or a musical performance (at a concert). Interestingly, the “right on the stage” example features Pitbull, an internationally acclaimed rapper who endorsed the campaign. Another endorsement is provided by the famous basketball player LeBron James, who also happens to be a co-founder of the company that produces the energy strips. Unlike the Ryanair example above, the marketers of this ad blatantly confirmed their intention to shock the receivers of the ad so as to make it more memorable. These energy strip producers also claimed they obtained substantial returns on the investment.46 Nonetheless, the adverts were the targets of much humor and negative comments over the Internet. Also, this series of adverts may have proved detrimental to both celebrities’ images.47

According to the GTVH, the SO is “obscene/non-obscene” while the LM is again “referential ambiguity”; the SI is respectively “physical exercise,” “intellectual activity” and “live performance.” The TAs of this campaign are probably “the product,” “the brand” and “the testimonials” themselves. This example shows how punning and the creative manipulation of language can also boomerang. On the one hand, it can be argued that the potential offensiveness of the ad has served the goal of the ad’s becoming a trend topic on the Internet. Yet part of this success resulted in the receivers ridiculing the brand and its products.

All in all, it can be claimed that advertisement campaigns based on punning are a risky business because they can often backfire. In the Ryanair ads, the company was forced to pay a fine and apologize publicly. In the Sheet Energy Strips campaign, formal apologies were not needed, yet the ads were deemed distasteful, with consequent detrimental effects on the company itself.

p.139

Verbal and visual humor

As mentioned earlier, advertisers can also exploit both the verbal and the referential content (i.e. meaning) that language ambiguity brings about. However, as Forceville suggests, adverts can make use of multimodal metaphors. Their target domain, which may be presented in the verbal or visual text (or a combination of the two), is placed where we would normally find something else, thus giving rise to a whole set of conceptualizations based on our background knowledge.48 Therefore, this composition produces an opposition between what is expected and what is actually presented in the advert. Bearing this in mind, I will examine a series of billboard and TV adverts that have made use of such creative devices in the attempt to be amusing and appealing, yet received the opposite response due to their controversial themes.

In 2006, the multinational corporation Sony published a billboard ad to launch its full white PlayStation Portable (PSP). In the attempt to cunningly show the battle between the previous all-black PSP and the brand-new white version, they created an advert featuring a stern white woman clutching a black woman by the chin with the accompanying copy “PlayStation Portable. White is coming.” The possibility of choosing between a white and black PSP visually punned with the color of the two models’ skin. However, the personified representations (a multimodal metaphor, as suggested above) of the two consoles are particularly interesting, as the white model appears to be in a dominant position. Interestingly, this campaign was launched in the Netherlands and was not intended to appear in the American market, or at least this is what the company maintained.49 Yet, as reported by The Guardian, Sony entrusted the campaign to TBWA, a notoriously provocative agency that tends to challenge conventions.50 Such an ad would be unthinkable in America, and it could be argued that Sony was very well aware of this. It stands to reason to suggest that, since ten years ago “viral videos” on YouTube and other platforms were in their infancy, they thought the ad could go unnoticed. Nonetheless, this image-based ad soon reached the USA and provoked opposing reactions. Some people suggested it had racist connotations, while others claimed it simply flagged the difference in color of the two products and was therefore harmless. Hence, the issue of intentionality here cannot be discounted altogether. Be that as it may, the audience’s negative reaction eventually led the company to withdraw the advert.

From a GTVH standpoint, the SO is “black/white”; yet I would argue that, as Tsakona suggested, this ad seems to elicit a multiple set of other SOs (e.g., “appropriate–inappropriate,” “black/white race,” “good–bad”) depending on the audience’s individual sensitivity to the underlying “black/white” opposition and the controversial theme of racialization it (inadvertently?) evokes. The LM in this case is “analogy” as it is based on a “multimodal metaphor” that maps the features of the two consoles onto the two models; the SI is “a battle.” In general terms, the TA can be said to be the black console that is being challenged by the white one. If we consider Sony’s claim, their prospective audience was the Dutch market, where they probably thought the “black/white” joke would not be taboo. Conversely, the American audience perceived it in more offensive terms as it flies in the face of the political correctness movement. Clearly, the line between what is considered humorously acceptable is extremely blurred here and it may depend on several factors, including the cultural and historical background.

p.140

Research in marketing has demonstrated that appealing to intrinsically hedonic needs, such as sexual instincts and appetites, is likely to enhance consumers’ motivation, opportunities and ability to process brand information in an advertisement.51 Yet, like humor, sex is culture-bound. As Biswas et al.’s analysis of humor and sex appeal in advertising has demonstrated, the French and Americans do make different uses of these phenomena. However, these scholars have looked at these variables separately. By contrast, the ad shown at the webpage link below is an interesting example that combines humor and sex via its verbal text and image. It was launched in 2009 in Singapore by Burger King (a.k.a. BK), a global chain of fast-food hamburger restaurants founded in 1954 in Miami, Florida.

See the image of the advertisement here: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11018413/Burger-King-raped-my-face-claims-model-on-angry-YouTube-video.html.

As can be seen, the billboard shows a girl facing a large seven-inch hamburger. The image referentially plays with the idea of oral sex since the sandwich roll is metaphorically associated with a penis that is placed just in front of a wide-eyed girl with an open red-lipsticked mouth. The incongruity breaks the frame of expectations52 (regarding food) that is recast on the sex domain, thus resulting in a humorous effect. Moreover, the copy of the advert “It’ll blow your mind” is a homonymic reference to the slang expression for fellatio (i.e. “give someone a blow job”). From the GTVH point of view, the SO is “sex/no-sex” or “obscene/non-obscene,” while the LM is again “analogy” and “multimodal metaphor”; the SI is fast-food eating and sexual intercourse while the TA (strictly speaking) is the girl in the picture.

The sexual innuendo in this sudden burst advert was immediately criticized as distasteful and repulsive. It is likely that the audience also transferred the disparaging humor targeting the girl in the picture to women at large, since the ad also seems to give rise to further opposition such as “men’s domination versus women’s oppression,” etc. Once again, the corporation’s spokesperson tried to respond to the customers’ ire by saying:

[t]his print ad is running to support a limited time promotion in the Singapore market and is not running in the U.S. or any other markets. The campaign is supported by the franchisee in Singapore and has generated positive consumer sales around this limited time product offer in that market.53

Interestingly, this campaign also stirred even more controversy a few years later, when the model seen in the billboard claimed the picture was taken without her knowledge or consent. As reported in The Telegraph by Radhika Sanghani, the woman posted a video on YouTube stating “Burger King raped my face” and encouraged people to boycott the fast-food chain.54 Although the video is no longer available and the model’s boycotting campaign was probably unsuccessful, reactions and debate revolving around the controversy this advert unleashed can still be found on YouTube, along with several related comments.55

The likelihood of carrying out successful boycotting campaigns is further demonstrated by the next two examples. Unlike space-based (i.e. print) adverts, these are instances of time-based (i.e. TV) ads, which stirred up a great deal of controversy from the social point of view and forced the company proposing the ads to withdraw them. Both adverts under scrutiny here were created to advertise Huggies diapers by Kimberly-Clark, an American multinational corporation that produces mostly paper-based products. Interestingly, each advert was conceived to target respectively the US and the Italian market by playing with stereotyped and biased ideas. In the case of the American advert launched in 2012, the ad playfully joked about the fact that fathers are not used to changing diapers or helping their wives/partners with babies in general. The video advert shows a group of fathers left alone in a house for five days with their children while the mothers enjoy some time to themselves. A peppy, fast-paced soundtrack accompanies the images while a voiceover message is broadcast. The fathers are shown struggling to change their babies’ diapers because they were more interested in watching sport events on the television, etc.:

p.141

To prove Huggies diapers and wipes can handle anything, we put them to the toughest test imaginable: dads! Alone with their babies in one house for five days . . . While we gave moms well deserved time off. How did Huggies products hold up to daddyhood? The world is about to find out.

The final headline read: “Huggies Dad Test. Coming Soon.”

From a GTVH point of view, the humor appears to stem from the “normal–abnormal” SO, which produces an incongruity between the script of normal parental duties and related expectations (e.g., efficient care of their offspring) and fathers’ (expected) ineptitude. The LM here is “exaggeration” and “role exchanges”; the SI is “father attending to toddlers and children” while the NS is “TV advertisement” and the TA is “the fathers on the ad” and “fathers in general.” The generalization and stereotyped ideas the advert reflects resulted in a heated debate among those fathers who probably felt they were the butt of the joke, rather than fathers in general. On Facebook, they gave vent to their disappointment at being pictured as utterly helpless.56 Chris Routhly launched the “We’re Dads, Huggies. Not Dummies” petition, which received more than 1,000 signatures in less than a week. This led Kimberly-Clark to withdraw the offending advert and publish the following statement: “We have heard the feedback from dads (. . .) We recognize our intended message did not come through and that we need to do a better job communicating the campaign’s overall message (. . .).” Interestingly, the video can still be found on YouTube and thus far it has been watched 7,094 times with the following feedback: 12 dislikes and only 2 likes. One of the comments found below is:

It is so utterly wrong to continually depict husbands and fathers as infantile buffoons, unable to grasp simple concepts or make decisions. How many ads have we seen where the kids and wife roll their eyes, as “stupid Dad” has no clue what he’s doing? As others have said, reverse the gender and see how funny it is.57

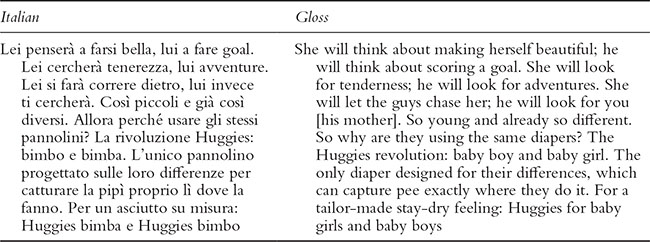

In 2015, Kimberly-Clark launched an advertising campaign for Huggies in Italy. This time the supposed overall message of the advert was to encourage parents to buy diapers specifically made for baby girls or baby boys on the basis of the physical differences. However, in order to underline these physical differences, the advertiser exploited stereotyped images regarding gender roles. In the TV advert a mother is shown playing with two toddlers (a girl and a boy) while the voiceover message reported in Table 3.6.2 is heard (an English translation is provided in the right-hand column).

Each of the statements that fosters a polarized gender difference is matched with images that contribute to create visual metaphors in different parts of the whole text. For instance, the baby girl on screen looks more feminine and caring while playing with dolls; the boy plays with a ball and later runs to hug his mother. They can therefore be seen as instances of punctual hyperdetermination.58 Hence, according to the underlying message of this advert, boys are likely to grow up to become footballers (and womanizers) while girls will mainly concentrate on being beautiful and getting chased by men. In addition, girls are pictured as constantly searching for love and affection and boys as mother-dependent. In GTVH, the advert can be explained as SO “normal–abnormal,” as not all baby girls will want to become loving Barbie-like women and not all baby boys will want to be mother-dependent footballers. The LM is again “exaggeration” and the TA are “babies that will be adults.” It stands to reason that this attempt to humorously play on gender-based stereotypes has given rise to a series of script oppositions (“sex/no-sex,” “men are womanizers/women are stupid, etc.) that were obviously unintended or unforeseen by the marketers. The problem here lies in the fact that the target audience, mostly comprising mothers, felt particularly offended by the advert as they probably perceived their own children and themselves to be the butt of the joke. Therefore, they generated petitions to remove the advert and boycott Huggies in the stores. Eventually the ad was modified to avoid such references.59 Clearly, the topic itself here is not taboo, but its inherent sexism was perceived as more disturbing than its potential humor.

p.142

Table 3.6.2 Italian “Baby boy and baby girl Huggies” advert

These examples show the extent to which the world has changed in the last couple of decades. Waller’s 1999 study found that, out of all issues, women were most offended by sexist behavior.60 Conversely, the Huggies ads targeted men from a sexist point of view, which was demonstrated to be equally disturbing for men. It is also worth noting that in the past, such ads might have done limited damage, but today’s interconnected world allows for fast and easy access to news by virtually everyone. The line between businesses influencing the public and vice versa is undoubtedly becoming blurred. More than ever, companies are not willing to risk losing their positive image and potential returns over unhappy customers. Hence, they quickly react to their feedback.

Concluding remarks

The examples presented in this study have attempted to offer both a local and global view of the function(s) of humor in advertising, be it inadvertent or intentional. Some examples have shown how advertisers creatively manipulate language. The adverts by Sharp etc. demonstrate their ability to play with language and involve the target buyers so as to promote a positive image and enhance sales. Nevertheless, some adverts have proved to be unsuccessful (if not total failures) due to the customers’ negative reactions and/or the community’s active participation in the debate the ads sparked. The Sony PSP and BK campaigns have shown how the exploitation of the verbal and visual texts can evoke a series of script oppositions at different levels within the same pool of target buyers. Adverts based on sensitive topics such as race and gender may involve metaphoric representations that can boomerang (e.g., by stirring up the customer’s discontent and fomenting boycotting campaigns) and have social and economic implications for the brands. The present analysis has benefited from the application of the GTVH, which has been able to show how several billboard and TV adverts can exploit the verbal text, or the verbal text in combination with the non-verbal text, to evoke a set of multilayered script oppositions and incongruities. In the case of potentially humorous adverts based on controversial themes, the oppositions and incongruities also seem to result in different targets of disparagement. This is proved by the audience’s different reactions to the adverts.

p.143

The analysis could certainly be expanded to include other local contexts and sectors, which may contribute to a better understanding of the social and cultural implications of the phenomenon of humor in ads. For example, further research could concentrate on the cross-cultural use and appreciation of humor by looking at instances of translated adverts. Due to space limitations, this issue could not be addressed here, but many examples of (un)intended humorous adverts can be found online and in literature.61 In addition, the linguistic and cultural reasons for the failure of cross-cultural communication via advertising certainly deserve further investigation. Unfortunately, statistical data regarding returns from challenging or controversial adverts are probably extremely difficult to retrieve, and it is unlikely that companies will provide them. Nonetheless, it would be of enormous interest to verify the empirical effectiveness, or lack thereof, of such selling strategies.

In any case, this chapter has hopefully contributed to shedding some light on the importance that various forms of humor have in advertising. Most importantly, it has offered a wealth of examples showing how humor is a delicate issue that needs to be handled carefully, especially in today’s hyper-politically correct world, in which seeking social involvement via advertising may backfire, resulting in the potential buyers’ turning against the company or brand itself.

References

1 Nash, W. (1985), The Language of Humour: Style and Technique in Comic Discourse, London and New York, Longman.

2 Norrick, N. R. (1993), Conversational Joking: Humor in Everyday Talk, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

3 Berger, A. A. (2015), Ads, Fads, and Consumer Culture: Advertising’s Impact on American Character and Society, Fifth Edition, Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

4 Beard, F. K. (2008), Advertising and audience offense: The role of intentional humor, Journal of Marketing Communications 14 (1): 1–17.

5 Raskin, V. (1985), Semantic Mechanisms of Humour, Dordrecht, D. Reidel.

6 Attardo, S. (1994), Linguistic Theories of Humour, Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter; Attardo, S. (2001), Humorous Texts: A Semantic and Pragmatic Analysis, Berlin and New York, Mouton de Gruyter; Oring, E. (2003), Engaging Humour, Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press.

7 Chiaro, D. (1992), The Language of Jokes. Analysing Verbal Play, London and New York, Routledge; Nash, W. (1985), The Language of Humour: Style and Technique in Comic Discourse, London and New York, Longman.

8 Palmer, J. (1994), Taking Humour Seriously, London and New York, Routledge; Morreall, J. (1983), Taking Laughter Seriously, Albany, State University of New York.

p.144

9 Oring, op. cit.

10 Attardo (1994), op. cit.

11 Attardo (1994), op. cit.

12 Norrick, op cit., Palmer, op. cit.; Critchley, S. (2002), On Humour, London, Routledge; Billig, M. (2005), Laughter and Ridicule: Towards a Social Critique of Humour, London, Sage.

13 Raskin, op. cit.

14 Attardo (1994), op. cit.

15 Ritchie, G. (2000), Describing verbally expressed humour, in Proceedings of AISB Symposium on Creative and Cultural Aspects and Applications of AI and Cognitive Science, April 2000, Birmingham: 71–78, Chiaro, D. (2005), Foreword: Verbally expressed humour and translation: An overview of a neglected field, Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 18 (2): 135–145.

16 Attardo (1994), op. cit.

17 Attardo (1994), op. cit.

18 Tsakona, V. (2009), Language and image interaction in cartoons: Towards a multimodal theory of humor, Journal of Pragmatics 41: 1171–1188.

19 Attardo (2001), op. cit.

20 Tsakona, op. cit.

21 Gérin, A. (2013), A second look at laughter: Humor in visual arts, Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 26 (1): 155–176.

22 Forceville, C. (2007), Multimodal metaphor in ten Dutch TV commercials, The Public Journal of Semiotics 1 (1): 15–34.

23 Simpson and Mayr, op. cit.

24 MacInnis, D. J., Moorman, C., and Jaworski, B. J. (1991), Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads, Journal of Marketing 55 (4): 32–53.

25 MacInnis, Moorman, and Jaworski, op. cit.

26 Catanescu, C. and Tom, G. (2001), Types of humor in television and magazine advertising, Review of Business 22 (1): 92–96.

27 Bernstein, D. (1974), Creative Advertising, London, Longman.

28 Speck, P. S. (1991), The humorous message taxonomy: A framework for the study of humorous ads, Current Issues & Research in Advertising 13 (1): 1–44.

29 Morreall, J. (1983), Taking Laughter Seriously, Albany, State University of New York Press.

30 Raskin, op. cit.

31 Speck, op. cit.

32 Gérin, op. cit.

33 Beard, op. cit.

34 Raskin, op. cit.

35 Hatzithomas, L., Boutsouki, C., and Zotos, Y. (2016), The role of economic conditions on humor generation and attitude towards humorous TV commercials, Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 29 (4): 483–505.

36 Attardo (1994), op. cit.

37 Reuters (08/04/2008), http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mexico-absolut-idUSN0729018920080409 [Accessed March 24, 2016].

38 Biswas, A., Olsen, J. E., and Carlet, V. (1992), A comparison of print advertisements from the United States and France, Journal of Advertising 21 (4): 73–81.

39 Raskin, op. cit.

40 Raskin, op. cit.

41 Durant and Lambrou, op. cit.

42 Tsakona, op. cit.

43 Attardo (2001), op. cit.

44 BBC (04/02/2004), Ryanair advert dubbed “offensive,” http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/3456423.stm [Accessed March 24, 2016].

45 BBC, op. cit.

p.145

46 Del Rey, J. (31/10/2011), How LeBron and an unusual adman linked up to launch for Sheets Energy Strips, http://adage.com/article/news/lebron-unusual-adman-linked-sheets-energy-strips/230723/ [Accessed November 24, 2016].

47 Nudd, T. (16/09/2011), Worst Ad Campaign of the Year? Sheet Energy Strips, http://www.adweek.com/adfreak/worst-ad-campaign-year-sheets-energy-strips-134913 [Accessed November 24, 2016].

48 Forceville, op. cit.

49 Tolilo, Stephen (12/07/2006), Sony pulls Dutch PSP ad deemed racist by American critics, http://www.mtv.com/news/1536222/sony-pulls-dutch-psp-ad-deemed-racist-by-american-critics/ [Accessed November 24, 2016].

50 Guardian (05/07/2006), Sony ad provokes race accusations, http://www.theguardian.com/technology/gamesblog/2006/jul/05/sonyadcasues [Accessed March 24, 2016].

51 MacInnis, Moorman, and Jaworski, op. cit., 35.

52 Tsakona, op. cit.

53 Miller, R. J. (2009), Critics cringe at ad for Burger King’s latest sandwich, FoxNews, June 30, http://www.foxnews.com/story/2009/06/30/critics-cringe-at-ad-for-burger-king-latest-sandwich.html [Accessed November 24, 2016].

54 Sanghani, R. (2014), “Burger King raped my face”, claims model on angry YouTube video, The Telegraph, August 7, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11018413/Burger-King-raped-my-face-claims-model-on-angry-YouTube-video.html [Accessed March 24, 2016].

55 Cf. “Model Says She Was ‘Face Raped’ by Burger King’s ‘Seven Incher’ Blowjob Ad,” and related comments, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B2ePS90LZvE [Accessed November 30, 2016].

56 Harrison, J. (2012), Huggies pulls ads after dads insulted, ABC Network, March 14, http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/lifestyle/2012/03/huggies-pulls-ads-after-dads-insulted/ [Accessed March 24, 2016].

57 Huggies Dad Test, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j7kX8ZKylD4 [Accessed March 24, 2016].

58 Attardo (1994), op. cit.; Tsakona, op. cit.

59 Successful petition to remove the Huggies advert in Italy, https://www.change.org/p/huggies-rimozione-campagna-pubblicitaria-huggies-bimbo-bimba [Accessed March 24, 2016].

60 Waller, D. S. (1999), Attitudes toward offensive advertising: An Australian study, The Journal of Consumer Marketing 16 (3): 288–294.

61 Durant and Lambrou, op. cit.; Simpson and Mayr, op. cit.