8 Designing Your Web Database

NOW THAT YOU ARE FAMILIAR WITH THE BASICS of PHP, you can begin looking at integrating a database into your scripts. As you might recall, Chapter 2, “Storing and Retrieving Data,” described the advantages of using a relational database instead of a flat file. They include

![]() RDBMSs can provide faster access to data than flat files.

RDBMSs can provide faster access to data than flat files.

![]() RDBMSs can be easily queried to extract sets of data that fit certain criteria.

RDBMSs can be easily queried to extract sets of data that fit certain criteria.

![]() RDBMSs have built-in mechanisms for dealing with concurrent access so that you, as a programmer, don’t have to worry about it.

RDBMSs have built-in mechanisms for dealing with concurrent access so that you, as a programmer, don’t have to worry about it.

![]() RDBMSs provide random access to your data.

RDBMSs provide random access to your data.

![]() RDBMSs have built-in privilege systems.

RDBMSs have built-in privilege systems.

For some concrete examples, using a relational database allows you to quickly and easily answer queries about where your customers are from, which of your products is selling the best, or what types of customers spend the most. This information can help you improve the site to attract and keep more users but would be very difficult to distill from a flat file.

The database that you will use in this part of the book is MySQL. Before we get into MySQL specifics in the next chapter, we need to discuss

![]() Relational database concepts and terminology

Relational database concepts and terminology

![]() Designing your web database

Designing your web database

![]() Web database architecture

Web database architecture

You will learn the following in this part of the book:

![]() Chapter 9, “Creating Your Web Database,” covers the basic configuration you will need to connect your MySQL database to the Web. You will learn how to create users, databases, tables, and indexes, and learn about MySQL’s different storage engines.

Chapter 9, “Creating Your Web Database,” covers the basic configuration you will need to connect your MySQL database to the Web. You will learn how to create users, databases, tables, and indexes, and learn about MySQL’s different storage engines.

![]() Chapter 10, “Working with Your MySQL Database,” explains how to query the database and add, delete, and update records, all from the command line.

Chapter 10, “Working with Your MySQL Database,” explains how to query the database and add, delete, and update records, all from the command line.

![]() Chapter 11, “Accessing Your MySQL Database from the Web with PHP,” explains how to connect PHP and MySQL together so that you can use and administer your database from a web interface. You will learn two methods of doing this: using PHP’s MySQL Improved Extension (mysqli) and using the PEAR:DB database abstraction layer.

Chapter 11, “Accessing Your MySQL Database from the Web with PHP,” explains how to connect PHP and MySQL together so that you can use and administer your database from a web interface. You will learn two methods of doing this: using PHP’s MySQL Improved Extension (mysqli) and using the PEAR:DB database abstraction layer.

![]() Chapter 12, “Advanced MySQL Administration,” covers MySQL administration in more detail, including details of the privilege system, security, and optimization.

Chapter 12, “Advanced MySQL Administration,” covers MySQL administration in more detail, including details of the privilege system, security, and optimization.

![]() Chapter 13, “Advanced MySQL Programming,” covers the storage engines in more detail, including coverage of transactions, full text search, and stored procedures.

Chapter 13, “Advanced MySQL Programming,” covers the storage engines in more detail, including coverage of transactions, full text search, and stored procedures.

Relational Database Concepts

Relational databases are, by far, the most commonly used type of database. They depend on a sound theoretical basis in relational algebra. You don’t need to understand relational theory to use a relational database (which is a good thing), but you do need to understand some basic database concepts.

Tables

Relational databases are made up of relations, more commonly called tables. A table is exactly what it sounds like—a table of data. If you’ve used an electronic spreadsheet, you’ve already used a table.

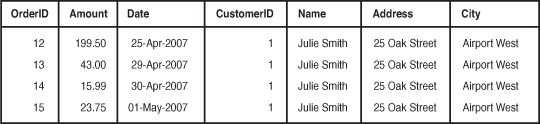

Look at the sample table in Figure 8.1. It contains the names and addresses of the customers of a bookstore named Book-O-Rama.

Figure 8.1 Book-O-Rama’s customer details are stored in a table.

The table has a name (Customers); a number of columns, each corresponding to a different piece of data; and rows that correspond to individual customers.

Columns

Each column in the table has a unique name and contains different data. Additionally, each column has an associated data type. For instance, in the Customers table in Figure 8.1, you can see that CustomerID is an integer and the other three columns are strings. Columns are sometimes called fields or attributes.

Rows

Each row in the table represents a different customer. Because of the tabular format, each row has the same attributes. Rows are also called records or tuples.

Values

Each row consists of a set of individual values that correspond to columns. Each value must have the data type specified by its column.

Keys

You need to have a way of identifying each specific customer. Names usually aren’t a very good way of doing this. If you have a common name, you probably understand why. Consider Julie Smith from the Customers table, for example. If you open your telephone directory, you may find too many listings of that name to count.

You could distinguish Julie in several ways. Chances are, she’s the only Julie Smith living at her address. Talking about “Julie Smith, of 25 Oak Street, Airport West” is pretty cumbersome and sounds too much like legalese. It also requires using more than one column in the table.

What we have done in this example, and what you will likely do in your applications, is assign a unique CustomerID. This is the same principle that leads to your having a unique bank account number or club membership number. It makes storing your details in a database easier. An artificially assigned identification number can be guaranteed to be unique. Few pieces of real information, even if used in combination, have this property.

The identifying column in a table is called the key or the primary key. A key can also consist of multiple columns. If, for example, you choose to refer to Julie as “Julie Smith, of 25 Oak Street, Airport West,” the key would consist of the Name, Address, and City columns and could not be guaranteed to be unique.

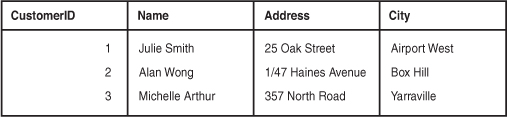

Databases usually consist of multiple tables and use a key as a reference from one table to another. Figure 8.2 shows a second table added to the database. This one stores orders placed by customers. Each row in the Orders table represents a single order, placed by a single customer. You know who the customer is because you store her CustomerID. You can look at the order with OrderID 2, for example, and see that the customer with CustomerID 1 placed it. If you then look at the Customers table, you can see that CustomerID 1 refers to Julie Smith.

Figure 8.2 Each order in the Orders table refers to a customer from the Customers table.

The relational database term for this relationship is foreign key. CustomerID is the primary key in Customers, but when it appears in another table, such as Orders, it is referred to as a foreign key.

You might wonder why we chose to have two separate tables. Why not just store Julie’s address in the Orders table? We explore this issue in more detail in the next section.

Schemas

The complete set of table designs for a database is called the database schema. It is akin to a blueprint for the database. A schema should show the tables along with their columns, and the primary key of each table and any foreign keys. A schema does not include any data, but you might want to show sample data with your schema to explain what it is for. The schema can be shown in informal diagrams as we have done, in entity relationship diagrams (which are not covered in this book), or in a text form, such as

Customers(CustomerID, Name, Address, City)

Orders(OrderID, CustomerID, Amount, Date)

Underlined terms in the schema are primary keys in the relation in which they are underlined. Italic terms are foreign keys in the relation in which they appear italic.

Relationships

Foreign keys represent a relationship between data in two tables. For example, the link from Orders to Customers represents a relationship between a row in the Orders table and a row in the Customers table.

Three basic kinds of relationships exist in a relational database. They are classified according to the number of elements on each side of the relationship. Relationships can be either one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many.

A one-to-one relationship means that one of each thing is used in the relationship. For example, if you put addresses in a separate table from Customers, they would have a one-to-one relationship between them. You could have a foreign key from Addresses to Customers or the other way around (both are not required).

In a one-to-many relationship, one row in one table is linked to many rows in another table. In this example, one Customer might place many Orders. In these relationships, the table that contains the many rows has a foreign key to the table with the one row. Here, we put the CustomerID into the Order table to show the relationship.

In a many-to-many relationship, many rows in one table are linked to many rows in another table. For example, if you have two tables, Books and Authors, you might find that one book was written by two coauthors, each of whom had written other books, on their own or possibly with other authors. This type of relationship usually gets a table all to itself, so you might have Books, Authors, and Books_Authors. This third table would contain only the keys of the other tables as foreign keys in pairs, to show which authors are involved with which books.

Designing Your Web Database

Knowing when you need a new table and what the key should be can be something of an art. You can read reams of information about entity relationship diagrams and database normalization, which are beyond the scope of this book. Most of the time, however, you can follow a few basic design principles. Let’s consider them in the context of Book-O-Rama.

Think About the Real-World Objects You Are Modeling

When you create a database, you are usually modeling real-world items and relationships and storing information about those objects and relationships.

Generally, each class of real-world objects you model needs its own table. Think about it: You want to store the same information about all your customers. If a set of data has the same “shape,” you can easily create a table corresponding to that data.

In the Book-O-Rama example, you want to store information about customers, the books that you sell, and details of the orders. The customers all have names and addresses. Each order has a date, a total amount, and a set of books that were ordered. Each book has an International Standard Book Number (ISBN), an author, a title, and a price.

This set of information suggests you need at least three tables in this database: Customers, Orders, and Books. This initial schema is shown in Figure 8.3.

Figure 8.3 The initial schema consists of Customers, Orders, and Books.

At present, you can’t tell from the model which books were ordered in each order. We will deal with this situation shortly.

Avoid Storing Redundant Data

Earlier, we asked the question: “Why not just store Julie Smith’s address in the Orders table?”

If Julie orders from Book-O-Rama on a number of occasions, which you hope she will, you will end up storing her data multiple times. You might end up with an Orders table that looks like the one shown in Figure 8.4.

Figure 8.4 A database design that stores redundant data takes up extra space and can cause anomalies in the data.

Such a design creates two basic problems:

![]() It’s a waste of space. Why store Julie’s details three times if you need to store them only once?

It’s a waste of space. Why store Julie’s details three times if you need to store them only once?

![]() It can lead to update anomalies—that is, situations in which you change the database and end up with inconsistent data. The integrity of the data is violated, and you no longer know which data is correct and which is incorrect. This scenario generally leads to losing information.

It can lead to update anomalies—that is, situations in which you change the database and end up with inconsistent data. The integrity of the data is violated, and you no longer know which data is correct and which is incorrect. This scenario generally leads to losing information.

Three kinds of update anomalies need to be avoided: modification, insertion, and deletion anomalies.

If Julie moves to a new house while she has pending orders, you will need to update her address in three places instead of one, doing three times as much work. You might easily overlook this fact and change her address in only one place, leading to inconsistent data in the database (a very bad thing). These problems are called modification anomalies because they occur when you are trying to modify the database.

With this design, you need to insert Julie’s details every time you take an order, so each time you must make sure that her details are consistent with the existing rows in the table. If you don’t check, you might end up with two rows of conflicting information about Julie. For example, one row might indicate that Julie lives in Airport West, and another might indicate she lives in Airport. This scenario is called an insertion anomaly because it occurs when data is being inserted.

The third kind of anomaly is called a deletion anomaly because it occurs (surprise, surprise) when you are deleting rows from the database. For example, imagine that after an order has been shipped, you delete it from the database. After all Julie’s current orders have been filled, they are all deleted from the Orders table. This means that you no longer have a record of Julie’s address. You can’t send her any special offers, and the next time she wants to order something from Book-O-Rama, you have to get her details all over again.

Generally, you should design your database so that none of these anomalies occur.

Use Atomic Column Values

Using atomic column values means that in each attribute in each row, you store only one thing. For example, you need to know what books make up each order. You could do this in several ways.

One solution would be to add a column to the Orders table listing all the books that have been ordered, as shown in Figure 8.5.

Figure 8.5 With this design, the Books Ordered attribute in each row has multiple values.

This solution isn’t a good idea for a few reasons. What you’re really doing is nesting a whole table inside one column—a table that relates orders to books. When you set up your columns this way, it becomes more difficult to answer such questions as “How many copies of Java 2 for Professional Developers have been ordered?” The system can no longer just count the matching fields. Instead, it has to parse each attribute value to see whether it contains a match anywhere inside it.

Because you’re really creating a table-inside-a-table, you should really just create that new table. This new table, called Order_Items, is shown in Figure 8.6.

Figure 8.6 This design makes it easier to search for particular books that have been ordered.

This table provides a link between the Orders and Books tables. This type of table is common when a many-to-many relationship exists between two objects; in this case, one order might consist of many books, and each book can be ordered by many people.

Choose Sensible Keys

Make sure that the keys you choose are unique. In this case, we created a special key for customers (CustomerID) and for orders (OrderID) because these real-world objects might not naturally have an identifier that can be guaranteed to be unique. You don’t need to create a unique identifier for books; this has already been done, in the form of an ISBN. For Order_Item, you can add an extra key if you want, but the combination of the two attributes OrderID and ISBN are unique as long as more than one copy of the same book in an order is treated as one row. For this reason, the table Order_Items has a Quantity column.

Think About What You Want to Ask the Database

Continuing from the previous section, think about what questions you want the database to answer. (For example, what are Book-O-Rama’s best-selling books?) Make sure that the database contains all the data required and that the appropriate links exist between tables to answer the questions you have.

Avoid Designs with Many Empty Attributes

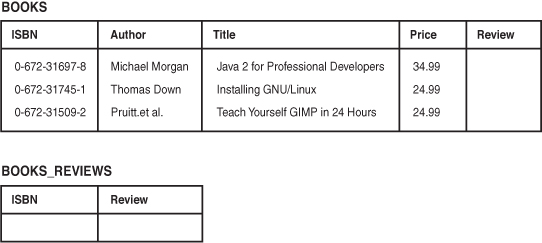

If you wanted to add book reviews to the database, you could do so in at least two ways. These two approaches are shown in Figure 8.7.

Figure 8.7 To add reviews, you can either add a Review column to the Books table or add a table specifically for reviews.

The first way means adding a Review column to the Books table. This way, there is a field for the Review to be added for each book. If many books are in the database, and the reviewer doesn’t plan to review them all, many rows won’t have a value in this attribute. This is called having a null value.

Having many null values in your database is a bad idea. It wastes storage space and causes problems when working out totals and other functions on numerical columns. When a user sees a null in a table, he doesn’t know whether it’s because this attribute is irrelevant, whether the database contains a mistake, or whether the data just hasn’t been entered yet.

You can generally avoid problems with many nulls by using an alternate design. In this case, you can use the second design proposed in Figure 8.7. Here, only books with a review are listed in the Book_Reviews table, along with their reviews.

Note that this design is based on the idea of having a single in-house reviewer; that is, a one-to-one relationship exists between Books and Reviews. If you want to include many reviews of the same book, this would be a one-to-many relationship, and you would need to go with the second design option. Also, with one review per book, you can use the ISBN as the primary key in the Book_Reviews table. If you have multiple reviews per book, you should introduce a unique identifier for each.

Summary of Table Types

You will usually find that your database design ends up consisting of two kinds of tables:

![]() Simple tables that describe a real-world object. They might also contain keys to other simple objects with which they have a one-to-one or one-to-many relationship. For example, one customer might have many orders, but an order is placed by a single customer. Thus, you put a reference to the customer in the order.

Simple tables that describe a real-world object. They might also contain keys to other simple objects with which they have a one-to-one or one-to-many relationship. For example, one customer might have many orders, but an order is placed by a single customer. Thus, you put a reference to the customer in the order.

![]() Linking tables that describe a many-to-many relationship between two real objects such as the relationship between

Linking tables that describe a many-to-many relationship between two real objects such as the relationship between Orders and Books. These tables are often associated with some kind of real-world transaction.

Web Database Architecture

Now that we’ve discussed the internal architecture of the database, we can look at the external architecture of a web database system and discuss the methodology for developing a web database system.

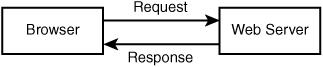

The basic operation of a web server is shown in Figure 8.8. This system consists of two objects: a web browser and a web server. A communication link is required between them. A web browser makes a request of the server. The server sends back a response. This architecture suits a server delivering static pages well. The architecture that delivers a database-backed website, however, is somewhat more complex.

Figure 8.8 The client/server relationship between a web browser and web server requires communication.

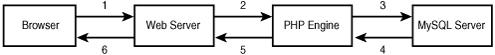

The web database applications you will build in this book follow a general web database structure like the one shown in Figure 8.9. Most of this structure should already be familiar to you.

Figure 8.9 The basic web database architecture consists of the web browser, web server, scripting engine, and database server.

A typical web database transaction consists of the following stages, which are numbered in Figure 8.9. Let’s examine the stages in the context of the Book-O-Rama example:

1. A user’s web browser issues an HTTP request for a particular web page. For example, using an HTML form, she might have requested a search for all the books at Book-O-Rama written by Laura Thomson. The search results page is called results.php.

2. The web server receives the request for results.php, retrieves the file, and passes it to the PHP engine for processing.

3. The PHP engine begins parsing the script. Inside the script is a command to connect to the database and execute a query (perform the search for books). PHP opens a connection to the MySQL server and sends on the appropriate query.

4. The MySQL server receives the database query, processes it, and sends the results—a list of books—back to the PHP engine.

5. The PHP engine finishes running the script, which usually involves formatting the query results nicely in HTML. It then returns the resulting HTML to the web server.

6. The web server passes the HTML back to the browser, where the user can see the list of books she requested.

The process is basically the same regardless of which scripting engine or database server you use. Often the web server software, PHP engine, and database server all run on the same machine. However, it is also quite common for the database server to run on a different machine. You might do this for reasons of security, increased capacity, or load spreading. From a development perspective, this approach is much the same to work with, but it might offer some significant advantages in performance.

As your applications increase in size and complexity, you will begin to separate your PHP applications into tiers—typically, a database layer that interfaces to MySQL, a business logic layer that contains the core of the application, and a presentation layer that manages the HTML output. However, the basic architecture shown in Figure 8.9 still holds; you just add more structure to the PHP section.

Further Reading

In this chapter, we covered some guidelines for relational database design. If you want to delve into the theory behind relational databases, you can try reading books by some of the relational gurus such as C.J. Date. Be warned, however, that the material can be comparatively theoretical and might not be immediately relevant to a commercial web developer. The average web database tends not to be that complicated.

Next

In the next chapter, you start setting up your MySQL database. First, you learn how to set up a MySQL database for the web, how to query it, and then how to query it from PHP.