1 PHP Crash Course

THIS CHAPTER GIVES YOU A QUICK OVERVIEW of PHP syntax and language constructs. If you are already a PHP programmer, it might fill some gaps in your knowledge. If you have a background using C, Perl Active Server Pages (ASP), or another programming language, it will help you get up to speed quickly.

In this book, you’ll learn how to use PHP by working through lots of real-world examples taken from our experiences building real websites. Often, programming textbooks teach basic syntax with very simple examples. We have chosen not to do that. We recognize that what you do is to get something up and running, and understand how the language is used, instead of plowing through yet another syntax and function reference that’s no better than the online manual.

Try the examples. Type them in or load them from the CD-ROM, change them, break them, and learn how to fix them again.

This chapter begins with the example of an online product order form to show how variables, operators, and expressions are used in PHP. It also covers variable types and operator precedence. You learn how to access form variables and manipulate them by working out the total and tax on a customer order.

You then develop the online order form example by using a PHP script to validate the input data. You examine the concept of Boolean values and look at examples using if, else, the ?: operator, and the switch statement. Finally, you explore looping by writing some PHP to generate repetitive HTML tables.

Key topics you learn in this chapter include

![]() Creating user-declared variables

Creating user-declared variables

![]() Understanding operators and precedence

Understanding operators and precedence

![]() Making decisions with

Making decisions with if, else, and switch

![]() Taking advantage of iteration using

Taking advantage of iteration using while, do, and for loops

Before You Begin: Accessing PHP

To work through the examples in this chapter and the rest of the book, you need access to a web server with PHP installed. To gain the most from the examples and case studies, you should run them and try changing them. To do this, you need a testbed where you can experiment.

If PHP is not installed on your machine, you need to begin by installing it or having your system administrator install it for you. You can find instructions for doing so in Appendix A, “Installing PHP and MySQL.” Everything you need to install PHP under Unix or Windows can be found on the accompanying CD-ROM.

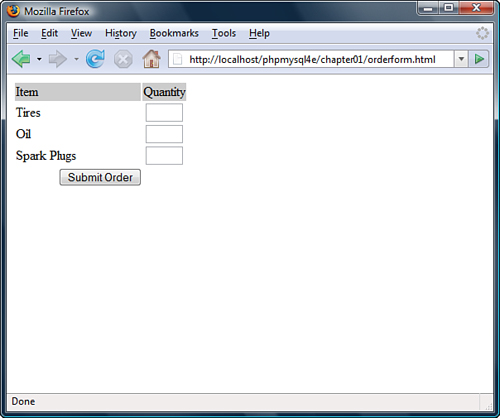

Creating a Sample Application: Bob’s Auto Parts

One of the most common applications of any server-side scripting language is processing HTML forms. You’ll start learning PHP by implementing an order form for Bob’s Auto Parts, a fictional spare parts company. You can find all the code for the examples used in this chapter in the directory called chapter01 on the CD-ROM.

Creating the Order Form

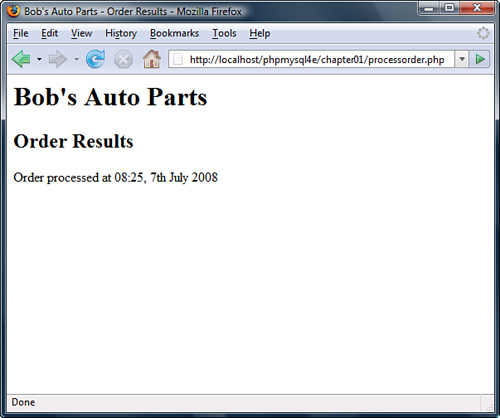

Bob’s HTML programmer has set up an order form for the parts that Bob sells. This relatively simple order form, shown in Figure 1.1, is similar to many you have probably seen while surfing. Bob would like to be able to know what his customers ordered, work out the total prices of their orders, and determine how much sales tax is payable on the orders.

Figure 1.1 Bob’s initial order form records only products and quantities.

Part of the HTML for this form is shown in Listing 1.1.

Listing 1.1 orderform.html —HTML for Bob’s Basic Order Form

<form action="processorder.php" method="post">

<table border="0">

<tr bgcolor="#cccccc">

<td width="150">Item</td>

<td width="15">Quantity</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Tires</td>

<td align="center"><input type="text" name="tireqty" size="3"

maxlength="3" /></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Oil</td>

<td align="center"><input type="text" name="oilqty" size="3"

maxlength="3" /></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Spark Plugs</td>

<td align="center"><input type="text" name="sparkqty" size="3"

maxlength="3" /></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="2" align="center"><input type="submit" value="Submit Order" /></td>

</tr>

</table>

</form>

Notice that the form’s action is set to the name of the PHP script that will process the customer’s order. (You’ll write this script next.) In general, the value of the action attribute is the URL that will be loaded when the user clicks the Submit button. The data the user has typed in the form will be sent to this URL via the method specified in the method attribute, either get (appended to the end of the URL) or post (sent as a separate message).

Also note the names of the form fields: tireqty, oilqty, and sparkqty. You’ll use these names again in the PHP script. Because the names will be reused, it’s important to give your form fields meaningful names that you can easily remember when you begin writing the PHP script. Some HTML editors generate field names like field23 by default. They are difficult to remember. Your life as a PHP programmer will be easier if the names you use reflect the data typed into the field.

You should consider adopting a coding standard for field names so that all field names throughout your site use the same format. This way, you can more easily remember whether, for example, you abbreviated a word in a field name or put in underscores as spaces.

Processing the Form

To process the form, you need to create the script mentioned in the action attribute of the form tag called processorder.php. Open your text editor and create this file. Then type in the following code:

<html>

<head>

<title>Bob’s Auto Parts - Order Results</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Bob’s Auto Parts</h1>

<h2>Order Results</h2>

</body>

</html>

Notice how everything you’ve typed so far is just plain HTML. It’s now time to add some simple PHP code to the script.

Embedding PHP in HTML

Under the <h2> heading in your file, add the following lines:

<?php

echo '<p>Order processed.</p>';

?>

Save the file and load it in your browser by filling out Bob’s form and clicking the Submit Order button. You should see something similar to the output shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Text passed to PHP’s echo construct is echoed to the browser.

Notice how the PHP code you wrote was embedded inside a normal-looking HTML file. Try viewing the source from your browser. You should see this code:

<html>

<head>

<title>Bob’s Auto Parts - Order Results</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Bob’s Auto Parts</h1>

<h2>Order Results</h2>

<p>Order processed.</p>

</body>

</html>

None of the raw PHP is visible because the PHP interpreter has run through the script and replaced it with the output from the script. This means that from PHP you can produce clean HTML viewable with any browser; in other words, the user’s browser does not need to understand PHP.

This example illustrates the concept of server-side scripting in a nutshell. The PHP has been interpreted and executed on the web server, as distinct from JavaScript and other client-side technologies interpreted and executed within a web browser on a user’s machine.

The code that you now have in this file consists of four types of text:

![]() HTML

HTML

![]() PHP tags

PHP tags

![]() PHP statements

PHP statements

![]() Whitespace

Whitespace

You can also add comments.

Most of the lines in the example are just plain HTML.

PHP Tags

The PHP code in the preceding example began with <?php and ended with ?>. This is similar to all HTML tags because they all begin with a less than (<) symbol and end with a greater than (>) symbol. These symbols (<?php and ?>) are called PHP tags. They tell the web server where the PHP code starts and finishes. Any text between the tags is interpreted as PHP. Any text outside these tags is treated as normal HTML. The PHP tags allow you to escape from HTML.

You can choose different tag styles. Let’s look at these tags in more detail.

There are actually four different styles of PHP tags. Each of the following fragments of code is equivalent:

<?php echo '<p>Order processed.</p>'; ?>

This is the tag style that we use in this book; it is the preferred PHP tag style. The server administrator cannot turn it off, so you can guarantee it will be available on all servers, which is especially important if you are writing applications that may be used on different installations. This tag style can be used with Extensible Markup Language (XML) documents. In general, we recommend you use this tag style.

![]() Short style

Short style

<? echo '<p>Order processed.</p>'; ?>

This tag style is the simplest and follows the style of a Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML) processing instruction. To use this type of tag—which is the shortest to type—you either need to enable the short_open_tag setting in your config file or compile PHP with short tags enabled. You can find more information on how to use this tag style in Appendix A. The use of this style is not recommended because it will not work in many environments as it is no longer enabled by default.

![]() SCRIPT style

SCRIPT style

<script language='php'> echo '<p>Order processed.</p>'; </script>

This tag style is the longest and will be familiar if you’ve used JavaScript or VBScript. You might use it if you’re using an HTML editor that gives you problems with the other tag styles.

![]() ASP style

ASP style

<% echo '<p>Order processed.</p>'; %>

This tag style is the same as used in Active Server Pages (ASP) or ASP.NET. You can use it if you have enabled the asp_tags configuration setting. You probably have no reason to use this style of tag unless you are using an editor that is geared toward ASP or ASP.NET. Note that, by default, this tag style is disabled.

PHP Statements

You tell the PHP interpreter what to do by including PHP statements between your opening and closing tags. The preceding example used only one type of statement:

echo '<p>Order processed.</p>';

As you have probably guessed, using the echo construct has a very simple result: It prints (or echoes) the string passed to it to the browser. In Figure 1.2, you can see the result is that the text Order processed. appears in the browser window.

Notice that there is a semicolon at the end of the echo statement. Semicolons separate statements in PHP much like periods separate sentences in English. If you have programmed in C or Java before, you will be familiar with using the semicolon in this way.

Leaving off the semicolon is a common syntax error that is easily made. However, it’s equally easy to find and to correct.

Whitespace

Spacing characters such as newlines (carriage returns), spaces, and tabs are known as whitespace. As you probably already know, browsers ignore whitespace in HTML. So does the PHP engine. Consider these two HTML fragments:

<h1>Welcome to Bob’s Auto Parts!</h1><p>What would you like to order today?</p>

and

<h1>Welcome to Bob’s

Auto Parts!</h1>

<p>What would you like

to order today?</p>

These two snippets of HTML code produce identical output because they appear the same to the browser. However, you can and are encouraged to use whitespace sensibly in your HTML as an aid to humans—to enhance the readability of your HTML code. The same is true for PHP. You don’t need to have any whitespace between PHP statements, but it makes the code much easier to read if you put each statement on a separate line. For example,

echo 'hello ';

echo 'world';

and

echo 'hello ';echo 'world';

are equivalent, but the first version is easier to read.

Comments

Comments are exactly that: Comments in code act as notes to people reading the code. Comments can be used to explain the purpose of the script, who wrote it, why they wrote it the way they did, when it was last modified, and so on. You generally find comments in all but the simplest PHP scripts.

The PHP interpreter ignores any text in comments. Essentially, the PHP parser skips over the comments, making them equivalent to whitespace.

PHP supports C, C++, and shell script–style comments.

The following is a C-style, multiline comment that might appear at the start of a PHP script:

/* Author: Bob Smith

Last modified: April 10

This script processes the customer orders.

*/

Multiline comments should begin with a /* and end with */. As in C, multiline comments cannot be nested.

You can also use single-line comments, either in the C++ style:

echo '<p>Order processed.</p>'; // Start printing order

or in the shell script style:

echo '<p>Order processed.</p>'; # Start printing order

With both of these styles, everything after the comment symbol (# or //) is a comment until you reach the end of the line or the ending PHP tag, whichever comes first.

In the following line of code, the text before the closing tag, here is a comment, is part of a comment. The text after the closing tag, here is not, will be treated as HTML because it is outside the closing tag:

// here is a comment ?> here is not

Adding Dynamic Content

So far, you haven’t used PHP to do anything you couldn’t have done with plain HTML.

The main reason for using a server-side scripting language is to be able to provide dynamic content to a site’s users. This is an important application because content that changes according to users’ needs or over time will keep visitors coming back to a site. PHP allows you to do this easily.

Let’s start with a simple example. Replace the PHP in processorder.php with the following code:

<?php

echo "<p>Order processed at ";

echo date('H:i, jS F Y'),

echo "</p>";

?>

You could also write this on one line, using the concatenation operator (.), as

<?php

echo "<p>Order processed at ".date('H:i, jS F Y')."</p>";

?>

In this code, PHP’s built-in date() function tells the customer the date and time when his order was processed. This information will be different each time the script is run. The output of running the script on one occasion is shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 PHP’s date() function returns a formatted date string.

Calling Functions

Look at the call to date(). This is the general form that function calls take. PHP has an extensive library of functions you can use when developing web applications. Most of these functions need to have some data passed to them and return some data.

Now look at the function call again:

date('H:i, jS F')

Notice that it passes a string (text data) to the function inside a pair of parentheses. The element within the parentheses is called the function’s argument or parameter. Such arguments are the input the function uses to output some specific results.

Using the date( ) Function

The date() function expects the argument you pass it to be a format string, representing the style of output you would like. Each letter in the string represents one part of the date and time. H is the hour in a 24-hour format with leading zeros where required, i is the minutes with a leading zero where required, j is the day of the month without a leading zero, S represents the ordinal suffix (in this case th), and F is the full name of the month.

For a full list of formats supported by date(), see Chapter 21, “Managing the Date and Time.”

Accessing Form Variables

The whole point of using the order form is to collect customers’ orders. Getting the details of what the customers typed is easy in PHP, but the exact method depends on the version of PHP you are using and a setting in your php.ini file.

Short, Medium, and Long Variables

Within your PHP script, you can access each form field as a PHP variable whose name relates to the name of the form field. You can recognize variable names in PHP because they all start with a dollar sign ($). (Forgetting the dollar sign is a common programming error.)

Depending on your PHP version and setup, you can access the form data via variables in three ways. These methods do not have official names, so we have nicknamed them short, medium, and long style. In any case, each form field on a page submitted to a PHP script is available in the script.

You may be able to access the contents of the field tireqty in the following ways:

$tireqty // short style

$_POST['tireqty'] // medium style

$HTTP_POST_VARS['tireqty'] // long style

In this example and throughout this book, we have used the medium style (that is, $_POST['tireqty']) for referencing form variables, but we have created short versions of the variables for ease of use. However, we do so within the code and not automatically, as to do so automatically would introduce a security issue within the code.

For your own code, you might decide to use a different approach. To make an informed choice, look at the different methods:

![]() Short style (

Short style ($tireqty) is convenient but requires the register_globals configuration setting be turned on. For security reasons, this setting is turned off by default. This style makes it easy to make errors that could make your code insecure, which is why it is no longer the recommended approach. It would be a bad idea to use this style in a new code as the option is likely to disappear in PHP6.

![]() Medium style (

Medium style ($_POST['tireqty']) is the recommended approach. If you create short versions of variable names, based on the medium style (as we do in this book), it is not a security issue and instead is simply on ease-of-use issue.

![]() Long style (

Long style ($HTTP_POST_VARS['tireqty']) is the most verbose. Note, however, that it is deprecated and is therefore likely to be removed in the long term. This style used to be the most portable but can now be disabled via the register_long_arrays configuration directive, which improves performance. So again using it in new code is probably not a good idea unless you have reason to think that your software is particularly likely to be installed on old servers.

When you use the short style, the names of the variables in the script are the same as the names of the form fields in the HTML form. You don’t need to declare the variables or take any action to create these variables in your script. They are passed into your script, essentially as arguments are passed to a function. If you are using this style, you can just use a variable such as $tireqty. The field tireqty in the form creates the variable $tireqty in the processing script.

Such convenient access to variables is appealing, but before you simply turn on register_globals, it is worth considering why the PHP development team set it to off.

Having direct access to variables like this is very convenient, but it does allow you to make programming mistakes that could compromise your scripts’ security. With form variables automatically turned into global variables like this, there is no obvious distinction between variables that you have created and untrusted variables that have come directly from users.

If you are not careful to give all your own variables a starting value, your scripts’ users can pass variables and values as form variables that will be mixed with your own. If you choose to use the convenient short style of accessing variables, you need to give all your own variables a starting value.

Medium style involves retrieving form variables from one of the arrays $_POST, $_GET, or $_REQUEST. One of the $_GET or $_POST arrays holds the details of all the form variables. Which array is used depends on whether the method used to submit the form was GET or POST, respectively. In addition, a combination of all data submitted via GET or POST is also available through $_REQUEST.

If the form was submitted via the POST method, the data entered in the tireqty box will be stored in $_POST['tireqty']. If the form was submitted via GET, the data will be in $_GET['tireqty']. In either case, the data will also be available in $_REQUEST['tireqty'].

These arrays are some of the superglobal arrays. We will revisit the superglobals when we discuss variable scope later in this chapter.

Let’s look at an example that creates easier-to-use copies of variables.

To copy the value of one variable into another, you use the assignment operator, which in PHP is an equal sign (=). The following statement creates a new variable named $tireqty and copies the contents of $ POST ['tireqty'] into the new variable:

$tireqty = $_POST['tireqty'];

Place the following block of code at the start of the processing script. All other scripts in this book that handle data from a form contain a similar block at the start. Because this code will not produce any output, placing it above or below the <html> and other HTML tags that start your page makes no difference. We generally place such blocks at the start of the script to make them easy to find.

<?php

// create short variable names

$tireqty = $_POST['tireqty];

$oilqty = $_POST['oilqty'];

$sparkqty = $_POST['sparkqty'];

?>

This code creates three new variables—$tireqty, $oilqty, and $sparkqty—and sets them to contain the data sent via the POST method from the form.

To make the script start doing something visible, add the following lines to the bottom of your PHP script:

echo '<p>Your order is as follows: </p>';

echo $tireqty.' tires<br />';

echo $oilqty.'; bottles of oil<br />';

echo $sparkqty.'; spark plugs<br />';

At this stage, you have not checked the variable contents to make sure sensible data has been entered in each form field. Try entering deliberately wrong data and observe what happens. After you have read the rest of the chapter, you might want to try adding some data validation to this script.

Taking data directly from the user and outputting it to the browser like this is a risky practice from a security perspective. You should filter input data. We will start to cover input filtering in Chapter 4, “String Manipulation and Regular Expressions,” and discuss security in depth in Chapter 16, “Web Application Security.”

If you now load this file in your browser, the script output should resemble what is shown in Figure 1.4. The actual values shown, of course, depend on what you typed into the form.

Figure 1.4 The form variables the user typed in are easily accessible in processorder.php.

The following sections describe a couple of interesting elements of this example.

String Concatenation

In the sample script, echo prints the value the user typed in each form field, followed by some explanatory text. If you look closely at the echo statements, you can see that the variable name and following text have a period (.) between them, such as this:

echo $tireqty.' tires<br />';

This period is the string concatenation operator, which adds strings (pieces of text) together. You will often use it when sending output to the browser with echo. This way, you can avoid writing multiple echo commands.

You can also place simple variables inside a double-quoted string to be echoed. (Arrays are somewhat more complicated, so we look at combining arrays and strings in Chapter 4, “String Manipulation and Regular Expressions.”) Consider this example:

echo "$tireqty tires<br />";

This is equivalent to the first statement shown in this section. Either format is valid, and which one you use is a matter of personal taste. This process, replacing a variable with its contents within a string, is known as interpolation.

Note that interpolation is a feature of double-quoted strings only. You cannot place variable names inside a single-quoted string in this way. Running the following line of code

echo '$tireqty tires<br />';

simply sends "$tireqty tires<br />" to the browser. Within double quotation marks, the variable name is replaced with its value. Within single quotation marks, the variable name or any other text is sent unaltered.

Variables and Literals

The variables and strings concatenated together in each of the echo statements in the sample script are different types of things. Variables are symbols for data. The strings are data themselves. When we use a piece of raw data in a program like this, we call it a literal to distinguish it from a variable. $tireqty is a variable, a symbol that represents the data the customer typed in. On the other hand, ' tires<br />' is a literal. You can take it at face value. Well, almost. Remember the second example in the preceding section? PHP replaced the variable name $tireqty in the string with the value stored in the variable.

Remember the two kinds of strings mentioned already: ones with double quotation marks and ones with single quotation marks. PHP tries to evaluate strings in double quotation marks, resulting in the behavior shown earlier. Single-quoted strings are treated as true literals.

There is also a third way of specifying strings using the heredoc syntax (<<<), which will be familiar to Perl users. Heredoc syntax allows you to specify long strings tidily, by specifying an end marker that will be used to terminate the string. The following example creates a three-line string and echoes it:

echo <<<theEnd

line 1

line 2

line 3

theEnd

The token theEnd is entirely arbitrary. It just needs to be guaranteed not to appear in the text. To close a heredoc string, place a closing token at the start of a line.

Heredoc strings are interpolated, like double-quoted strings.

Understanding Identifiers

Identifiers are the names of variables. (The names of functions and classes are also identifiers; we look at functions and classes in Chapters 5, “Reusing Code and Writing Functions,” and 6, “Object-Oriented PHP.”) You need to be aware of the simple rules defining valid identifiers:

![]() Identifiers can be of any length and can consist of letters, numbers, and underscores.

Identifiers can be of any length and can consist of letters, numbers, and underscores.

![]() Identifiers cannot begin with a digit.

Identifiers cannot begin with a digit.

![]() In PHP, identifiers are case sensitive.

In PHP, identifiers are case sensitive. $tireqty is not the same as $TireQty. Trying to use them interchangeably is a common programming error. Function names are an exception to this rule: Their names can be used in any case.

![]() A variable can have the same name as a function. This usage is confusing, however, and should be avoided. Also, you cannot create a function with the same name as another function.

A variable can have the same name as a function. This usage is confusing, however, and should be avoided. Also, you cannot create a function with the same name as another function.

You can declare and use your own variables in addition to the variables you are passed from the HTML form.

One of the features of PHP is that it does not require you to declare variables before using them. A variable is created when you first assign a value to it. See the next section for details.

You assign values to variables using the assignment operator (=) as you did when copying one variable’s value to another. On Bob’s site, you want to work out the total number of items ordered and the total amount payable. You can create two variables to store these numbers. To begin with, you need to initialize each of these variables to zero by adding these lines to the bottom of your PHP script.

$totalqty = 0;

$totalamount = 0.00;

Each of these two lines creates a variable and assigns a literal value to it. You can also assign variable values to variables, as shown in this example:

$totalqty = 0;

$totalamount = $totalqty;

Examining Variable Types

A variable’s type refers to the kind of data stored in it. PHP provides a set of data types. Different data can be stored in different data types.

PHP’s Data Types

PHP supports the following basic data types:

![]() Integer—Used for whole numbers

Integer—Used for whole numbers

![]() Float (also called double)—Used for real numbers

Float (also called double)—Used for real numbers

![]() String—Used for strings of characters

String—Used for strings of characters

![]() Boolean—Used for

Boolean—Used for true or false values

![]() Array—Used to store multiple data items (see Chapter 3, “Using Arrays”)

Array—Used to store multiple data items (see Chapter 3, “Using Arrays”)

![]() Object—Used for storing instances of classes (see Chapter 6)

Object—Used for storing instances of classes (see Chapter 6)

Two special types are also available: NULL and resource. Variables that have not been given a value, have been unset, or have been given the specific value NULL are of type NULL. Certain built-in functions (such as database functions) return variables that have the type resource. They represent external resources (such as database connections). You will almost certainly not directly manipulate a resource variable, but frequently they are returned by functions and must be passed as parameters to other functions.

Type Strength

PHP is called weakly typed, or dynamically typed language. In most programming languages, variables can hold only one type of data, and that type must be declared before the variable can be used, as in C. In PHP, the type of a variable is determined by the value assigned to it.

For example, when you created $totalqty and $totalamount, their initial types were determined as follows:

$totalqty = 0;

$totalamount = 0.00;

Because you assigned 0, an integer, to $totalqty, this is now an integer type variable. Similarly, $totalamount is now of type float.

Strangely enough, you could now add a line to your script as follows:

$totalamount = 'Hello';

The variable $totalamount would then be of type string. PHP changes the variable type according to what is stored in it at any given time.

This ability to change types transparently on the fly can be extremely useful. Remember PHP “automagically” knows what data type you put into your variable. It returns the data with the same data type when you retrieve it from the variable.

Type Casting

You can pretend that a variable or value is of a different type by using a type cast. This feature works identically to the way it works in C. You simply put the temporary type in parentheses in front of the variable you want to cast.

For example, you could have declared the two variables from the preceding section using a cast:

$totalqty = 0;

$totalamount = (float)$totalqty;

The second line means “Take the value stored in $totalqty, interpret it as a float, and store it in $totalamount.” The $totalamount variable will be of type float. The cast variable does not change types, so $totalqty remains of type integer.

You can also use the built-in function to test and set type, which you will learn about later in this chapter.

Variable Variables

PHP provides one other type of variable: the variable variable. Variable variables enable you to change the name of a variable dynamically.

As you can see, PHP allows a lot of freedom in this area. All languages enable you to change the value of a variable, but not many allow you to change the variable’s type, and even fewer allow you to change the variable’s name.

A variable variable works by using the value of one variable as the name of another. For example, you could set

$varname = 'tireqty';

You can then use $$varname in place of $tireqty. For example, you can set the value of $tireqty as follows:

$$varname = 5;

This is exactly equivalent to

$tireqty = 5;

This approach might seem somewhat obscure, but we’ll revisit its use later. Instead of having to list and use each form variable separately, you can use a loop and variable to process them all automatically. You can find an example illustrating this in the section on for loops later in this chapter.

Declaring and Using Constants

As you saw previously, you can readily change the value stored in a variable. You can also declare constants. A constant stores a value just like a variable, but its value is set once and then cannot be changed elsewhere in the script.

In the sample application, you might store the prices for each item on sale as a constant. You can define these constants using the define function:

define('TIREPRICE', 100);

define('OILPRICE', 10);

define('SPARKPRICE', 4);

Now add these lines of code to your script. You now have three constants that can be used to calculate the total of the customer’s order.

Notice that the names of the constants appear in uppercase. This convention borrowed from C, makes it easy to distinguish between variables and constants at a glance. Following this convention is not required but will make your code easier to read and maintain.

One important difference between constants and variables is that when you refer to a constant, it does not have a dollar sign in front of it. If you want to use the value of a constant, use its name only. For example, to use one of the constants just created, you could type

echo TIREPRICE;

As well as the constants you define, PHP sets a large number of its own. An easy way to obtain an overview of them is to run the phpinfo() function:

phpinfo();

This function provides a list of PHP’s predefined variables and constants, among other useful information. We will discuss some of them as we go along.

One other difference between variables and constants is that constants can store only boolean, integer, float, or string data. These types are collectively known as scalar values.

Understanding Variable Scope

The term scope refers to the places within a script where a particular variable is visible. The six basic scope rules in PHP are as follows:

![]() Built-in superglobal variables are visible everywhere within a script.

Built-in superglobal variables are visible everywhere within a script.

![]() Constants, once declared, are always visible globally; that is, they can be used inside and outside functions.

Constants, once declared, are always visible globally; that is, they can be used inside and outside functions.

![]() Global variables declared in a script are visible throughout that script, but not inside functions.

Global variables declared in a script are visible throughout that script, but not inside functions.

![]() Variables inside functions that are declared as global refer to the global variables of the same name.

Variables inside functions that are declared as global refer to the global variables of the same name.

![]() Variables created inside functions and declared as static are invisible from outside the function but keep their value between one execution of the function and the next. (We explain this idea fully in Chapter 5.)

Variables created inside functions and declared as static are invisible from outside the function but keep their value between one execution of the function and the next. (We explain this idea fully in Chapter 5.)

![]() Variables created inside functions are local to the function and cease to exist when the function terminates.

Variables created inside functions are local to the function and cease to exist when the function terminates.

The arrays $_GET and $_POST and some other special variables have their own scope rules. They are known as superglobals or autoglobals and can be seen everywhere, both inside and outside functions.

The complete list of superglobals is as follows:

![]()

$GLOBALS—An array of all global variables (Like the global keyword, this allows you to access global variables inside a function—for example, as $GLOBALS['myvariable'].)

![]()

$_SERVER—An array of server environment variables

![]()

$_GET—An array of variables passed to the script via the GET method

![]()

$_POST—An array of variables passed to the script via the POST method

![]()

$_COOKIE—An array of cookie variables

![]()

$_FILES—An array of variables related to file uploads

![]()

$_ENV—An array of environment variables

![]()

$_REQUEST—An array of all user input including the contents of input including $_GET, $_POST, and $_COOKIE (but not including $_FILES since PHP 4.3.0)

![]()

$_SESSION—An array of session variables

We come back to each of these superglobals throughout the book as they become relevant.

We cover scope in more detail when we discuss functions and classes later in this chapter. For the time being, all the variables we use are global by default.

Using Operators

Operators are symbols that you can use to manipulate values and variables by performing an operation on them. You need to use some of these operators to work out the totals and tax on the customer’s order.

We’ve already mentioned two operators: the assignment operator (=) and the string concatenation operator (.). In the following sections, we describe the complete list.

In general, operators can take one, two, or three arguments, with the majority taking two. For example, the assignment operator takes two: the storage location on the left side of the = symbol and an expression on the right side. These arguments are called operands—that is, the things that are being operated upon.

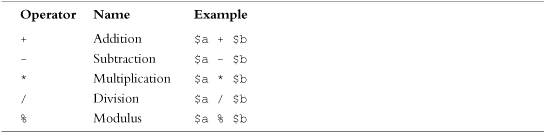

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators are straightforward; they are just the normal mathematical operators. PHP’s arithmetic operators are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 PHP’s Arithmetic Operators

With each of these operators, you can store the result of the operation, as in this example:

$result = $a + $b;

Addition and subtraction work as you would expect. The result of these operators is to add or subtract, respectively, the values stored in the $a and $b variables.

You can also use the subtraction symbol (-) as a unary operator—that is, an operator that takes one argument or operand—to indicate negative numbers, as in this example:

$a = -1;

Multiplication and division also work much as you would expect. Note the use of the asterisk as the multiplication operator rather than the regular multiplication symbol, and the forward slash as the division operator rather than the regular division symbol.

The modulus operator returns the remainder calculated by dividing the $a variable by the $b variable. Consider this code fragment:

$a = 27;

$b = 10;

$result = $a%$b;

The value stored in the $result variable is the remainder when you divide 27 by 10—that is, 7.

You should note that arithmetic operators are usually applied to integers or doubles. If you apply them to strings, PHP will try to convert the string to a number. If it contains an e or an E, it will be read as being in scientific notation and converted to a float; otherwise, it will be converted to an integer. PHP will look for digits at the start of the string and use them as the value; if there are none, the value of the string will be zero.

String Operators

You’ve already seen and used the only string operator. You can use the string concatenation operator to add two strings and to generate and store a result much as you would use the addition operator to add two numbers:

$a = "Bob’s ";

$b = "Auto Parts";

$result = $a.$b;

The $result variable now contains the string "Bob's Auto Parts".

Assignment Operators

You’ve already seen the basic assignment operator (=). Always refer to this as the assignment operator and read it as “is set to.” For example,

$totalqty = 0;

This line should be read as “$totalqty is set to zero.” We explain why when we discuss the comparison operators later in this chapter, but if you call it equals, you will get confused.

Values Returned from Assignment

Using the assignment operator returns an overall value similar to other operators. If you write

$a + $b

the value of this expression is the result of adding the $a and $b variables together. Similarly, you can write

$a = 0;

The value of this whole expression is zero.

This technique enables you to form expressions such as

$b = 6 + ($a = 5);

This line sets the value of the $b variable to 11. This behavior is generally true of assignments: The value of the whole assignment statement is the value that is assigned to the left operand.

When working out the value of an expression, you can use parentheses to increase the precedence of a subexpression, as shown here. This technique works exactly the same way as in mathematics.

Combined Assignment Operators

In addition to the simple assignment, there is a set of combined assignment operators. Each of them is a shorthand way of performing another operation on a variable and assigning the result back to that variable. For example,

$a += 5;

This is equivalent to writing

$a = $a + 5;

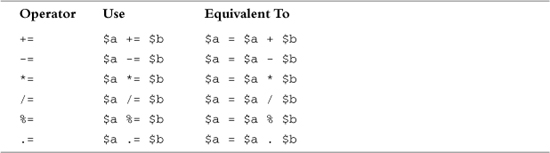

Combined assignment operators exist for each of the arithmetic operators and for the string concatenation operator. A summary of all the combined assignment operators and their effects is shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 PHP’s Combined Assignment Operators

Pre- and Post-Increment and Decrement

The pre- and post-increment (++) and decrement (--) operators are similar to the += and -= operators, but with a couple of twists.

All the increment operators have two effects: They increment and assign a value. Consider the following:

$a=4;

echo ++$a;

The second line uses the pre-increment operator, so called because the ++ appears before the $a. This has the effect of first incrementing $a by 1 and second, returning the incremented value. In this case, $a is incremented to 5, and then the value 5 is returned and printed. The value of this whole expression is 5. (Notice that the actual value stored in $a is changed: It is not just returning $a + 1.)

If the ++ is after the $a, however, you are using the post-increment operator. It has a different effect. Consider the following:

$a=4;

echo $a++;

In this case, the effects are reversed. That is, first, the value of $a is returned and printed, and second, it is incremented. The value of this whole expression is 4. This is the value that will be printed. However, the value of $a after this statement is executed is 5.

As you can probably guess, the behavior is similar for the -- operator. However, the value of $a is decremented instead of being incremented.

Reference Operator

The reference operator (&, an ampersand) can be used in conjunction with assignment. Normally, when one variable is assigned to another, a copy is made of the first variable and stored elsewhere in memory. For example,

$a = 5;

$b = $a;

These code lines make a second copy of the value in $a and store it in $b. If you subsequently change the value of $a, $b will not change:

$a = 7; // $b will still be 5

You can avoid making a copy by using the reference operator. For example,

$a = 5;

$b = &$a;

$a = 7; // $a and $b are now both 7

References can be a bit tricky. Remember that a reference is like an alias rather than like a pointer. Both $a and $b point to the same piece of memory. You can change this by unsetting one of them as follows:

unset($a);

Unsetting does not change the value of $b (7) but does break the link between $a and the value 7 stored in memory.

Comparison Operators

The comparison operators compare two values. Expressions using these operators return either of the logical values true or false depending on the result of the comparison.

The Equal Operator

The equal comparison operator (==, two equal signs) enables you to test whether two values are equal. For example, you might use the expression

$a == $b

to test whether the values stored in $a and $b are the same. The result returned by this expression is true if they are equal or false if they are not.

You might easily confuse == with =, the assignment operator. Using the wrong operator will work without giving an error but generally will not give you the result you wanted. In general, nonzero values evaluate to true and zero values to false. Say that you have initialized two variables as follows:

$a = 5;

$b = 7;

If you then test $a = $b, the result will be true. Why? The value of $a = $b is the value assigned to the left side, which in this case is 7. Because 7 is a nonzero value, the expression evaluates to true. If you intended to test $a == $b, which evaluates to false, you have introduced a logic error in your code that can be extremely difficult to find. Always check your use of these two operators and check that you have used the one you intended to use.

Using the assignment operator rather than the equals comparison operator is an easy mistake to make, and you will probably make it many times in your programming career.

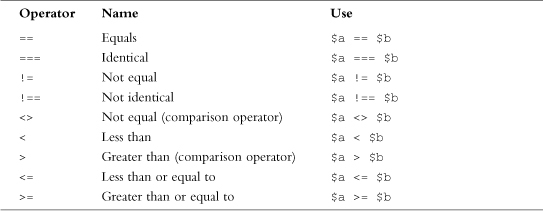

Other Comparison Operators

PHP also supports a number of other comparison operators. A summary of all the comparison operators is shown in Table 1.3. One to note is the identical operator (===), which returns true only if the two operands are both equal and of the same type. For example, 0==0 will be true, but 0===0 will not because one zero is an integer and the other zero is a string.

Table 1.3 PHP’s Comparison Operators

Logical Operators

The logical operators combine the results of logical conditions. For example, you might be interested in a case in which the value of a variable, $a, is between 0 and 100. You would need to test both the conditions $a >= 0 and $a <= 100, using the AND operator, as follows:

$a >= 0 && $a <=100

PHP supports logical AND, OR, XOR (exclusive or), and NOT.

The set of logical operators and their use is summarized in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 PHP’s Logical Operators

The and and or operators have lower precedence than the && and || operators. We cover precedence in more detail later in this chapter.

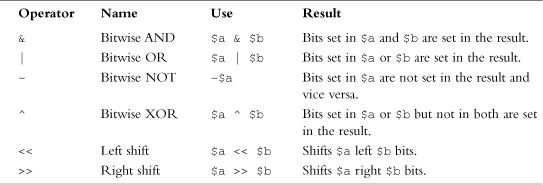

Bitwise Operators

The bitwise operators enable you to treat an integer as the series of bits used to represent it. You probably will not find a lot of use for the bitwise operators in PHP, but a summary is shown in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5 PHP’s Bitwise Operators

Other Operators

In addition to the operators we have covered so far, you can use several others.

The comma operator (,) separates function arguments and other lists of items. It is normally used incidentally.

Two special operators, new and ->, are used to instantiate a class and access class members, respectively. They are covered in detail in Chapter 6.

There are a few others that we discuss briefly here.

The Ternary Operator

The ternary operator (?:) takes the following form:

condition ? value if true : value if false

This operator is similar to the expression version of an if-else statement, which is covered later in this chapter.

A simple example is

($grade >= 50 ? 'Passed' : 'Failed')

This expression evaluates student grades to 'Passed' or 'Failed'.

The Error Suppression Operator

The error suppression operator (@) can be used in front of any expression—that is, anything that generates or has a value. For example,

$a = @(57/0);

Without the @ operator, this line generates a divide-by-zero warning. With the operator included, the error is suppressed.

If you are suppressing warnings in this way, you need to write some error handling code to check when a warning has occurred. If you have PHP set up with the track_errors feature enabled in php.ini, the error message will be stored in the global variable $php_errormsg.

The Execution Operator

The execution operator is really a pair of operators—a pair of backticks (``) in fact. The backtick is not a single quotation mark; it is usually located on the same key as the ~ (tilde) symbol on your keyboard.

PHP attempts to execute whatever is contained between the backticks as a command at the server’s command line. The value of the expression is the output of the command.

For example, under Unix-like operating systems, you can use

$out = `ls -la`;

echo '<pre>'.$out.'</pre>';

Or, equivalently on a Windows server, you can use

$out = `dir c:`;

echo '<pre>'.$out.'</pre>';

Either version obtains a directory listing and stores it in $out. It can then be echoed to the browser or dealt with in any other way.

There are other ways of executing commands on the server. We cover them in Chapter 19, “Interacting with the File System and the Server.”

Array Operators

There are a number of array operators. The array element operators ([]) enable you to access array elements. You can also use the => operator in some array contexts. These operators are covered in Chapter 3.

You also have access to a number of other array operators. We cover them in detail in Chapter 3 as well, but we included them here in Table 1.6 for completeness.

Table 1.6 PHP’s Array Operators

You will notice that the array operators in Table 1.6 all have equivalent operators that work on scalar variables. As long as you remember that + performs addition on scalar types and union on arrays—even if you have no interest in the set arithmetic behind that behavior—the behaviors should make sense. You cannot usefully compare arrays to scalar types.

The Type Operator

There is one type operator: instanceof. This operator is used in object-oriented programming, but we mention it here for completeness. (Object-oriented programming is covered in Chapter 6.)

The instanceof operator allows you to check whether an object is an instance of a particular class, as in this example:

class sampleClass{};

$myObject = new sampleClass();

if ($myObject instanceof sampleClass)

echo "myObject is an instance of sampleClass";

Working Out the Form Totals

Now that you know how to use PHP’s operators, you are ready to work out the totals and tax on Bob’s order form. To do this, add the following code to the bottom of your PHP script:

$totalqty = 0;

$totalqty = $tireqty + $oilqty + $sparkqty;

echo "Items ordered: ".$totalqty."<br />";

$totalamount = 0.00;

define('TIREPRICE', 100);

define('OILPRICE', 10);

define('SPARKPRICE', 4);

$totalamount = $tireqty * TIREPRICE

+ $oilqty * OILPRICE

+ $sparkqty * SPARKPRICE;

echo "Subtotal: $".number_format($totalamount,2)."<br />";

$taxrate = 0.10; // local sales tax is 10%

$totalamount = $totalamount * (1 + $taxrate);

echo "Total including tax: $".number_format($totalamount,2)."<br />";

If you refresh the page in your browser window, you should see output similar to Figure 1.5.

As you can see, this piece of code uses several operators. It uses the addition (+) and multiplication (*) operators to work out the amounts and the string concatenation operator (.) to set up the output to the browser.

Figure 1.5 The totals of the customer’s order have been calculated, formatted, and displayed.

It also uses the number_format() function to format the totals as strings with two decimal places. This is a function from PHP’s Math library.

If you look closely at the calculations, you might ask why the calculations were performed in the order they were. For example, consider this statement:

$totalamount = $tireqty * TIREPRICE

+ $oilqty * OILPRICE

+ $sparkqty * SPARKPRICE;

The total amount seems to be correct, but why were the multiplications performed before the additions? The answer lies in the precedence of the operators—that is, the order in which they are evaluated.

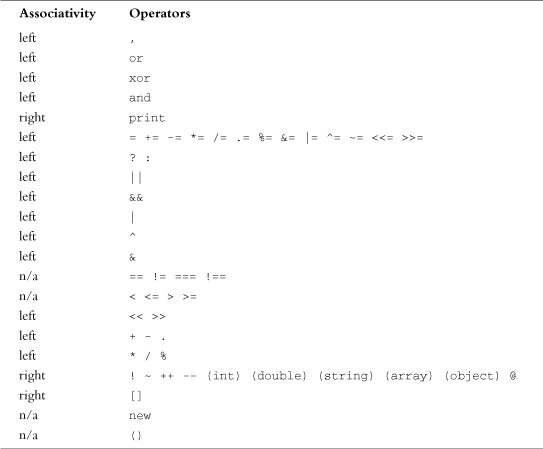

Understanding Precedence and Associativity

In general, operators have a set precedence, or order, in which they are evaluated. Operators also have an associativity, which is the order in which operators of the same precedence are evaluated. This order is generally left to right (called left for short), right to left (called right for short), or not relevant.

Table 1.7 shows operator precedence and associativity in PHP. In this table, operators with the lowest precedence are at the top, and precedence increases as you go down the table.

Table 1.7 Operator Precedence in PHP

Notice that we haven’t yet covered the operator with the highest precedence: plain old parentheses. The effect of using parentheses is to raise the precedence of whatever is contained within them. This is how you can deliberately manipulate or work around the precedence rules when you need to.

Remember this part of the preceding example:

$totalamount = $totalamount * (1 + $taxrate);

If you had written

$totalamount = $totalamount * 1 + $taxrate;

the multiplication operation, having higher precedence than the addition operation, would be performed first, giving an incorrect result. By using the parentheses, you can force the subexpression 1 + $taxrate to be evaluated first.

You can use as many sets of parentheses as you like in an expression. The innermost set of parentheses is evaluated first.

Also note one other operator in this table we have not yet covered: the print language construct, which is equivalent to echo. Both constructs generate output.

We generally use echo in this book, but you can use print if you find it more readable. Neither print nor echo is really a function, but both can be called as a function with parameters in parentheses. Both can also be treated as an operator: You simply place the string to work with after the keyword echo or print.

Calling print as a function causes it to return a value (1). This capability might be useful if you want to generate output inside a more complex expression but does mean that print is marginally slower than echo.

Using Variable Functions

Before we leave the world of variables and operators, let’s look at PHP’s variable functions. PHP provides a library of functions that enable you to manipulate and test variables in different ways.

Testing and Setting Variable Types

Most of the variable functions are related to testing the type of function. The two most general are gettype() and settype(). They have the following function prototypes; that is, this is what arguments expect and what they return:

string gettype(mixed var);

bool settype(mixed var, string type);

To use gettype(), you pass it a variable. It determines the type and returns a string containing the type name: bool, int, double (for floats), string, array, object, resource, or NULL. It returns unknown type if it is not one of the standard types.

To use settype(), you pass it a variable for which you want to change the type and a string containing the new type for that variable from the previous list.

You can use these functions as follows:

$a = 56;

echo gettype($a).'<br />';

settype($a, 'double'),

echo gettype($a).'<br />';

When gettype() is called the first time, the type of $a is integer. After the call to settype(), the type is changed to double.

PHP also provides some specific type-testing functions. Each takes a variable as an argument and returns either true or false. The functions are

![]()

is_array()—Checks whether the variable is an array.

![]()

is_double(), is_float(), is_real() (All the same function)—Checks whether the variable is a float.

![]()

is_long(), is_int(), is_integer() (All the same function)—Checks whether the variable is an integer.

![]()

is_string()—Checks whether the variable is a string.

![]()

is_bool()—Checks whether the variable is a boolean.

![]()

is_object()—Checks whether the variable is an object.

![]()

is_resource()—Checks whether the variable is a resource.

![]()

is_null()—Checks whether the variable is null.

![]()

is_scalar()—Checks whether the variable is a scalar, that is, an integer, boolean, string, or float.

![]()

is_numeric()—Checks whether the variable is any kind of number or a numeric string.

![]()

is_callable()—Checks whether the variable is the name of a valid function.

Testing Variable Status

PHP has several functions for testing the status of a variable. The first is isset(), which has the following prototype:

bool isset(mixed var);[;mixed var[,…]])

This function takes a variable name as an argument and returns true if it exists and false otherwise. You can also pass in a comma-separated list of variables, and isset() will return true if all the variables are set.

You can wipe a variable out of existence by using its companion function, unset(), which has the following prototype:

void unset(mixed var);[;mixed var[,…]])

This function gets rid of the variable it is passed.

The empty() function checks to see whether a variable exists and has a nonempty, nonzero value; it returns true or false accordingly. It has the following prototype:

bool empty(mixed var);

Let’s look at an example using these three functions.

Try adding the following code to your script temporarily:

echo 'isset($tireqty): '.isset($tireqty).'<br />';

echo 'isset($nothere): '.isset($nothere).'<br />';

echo 'empty($tireqty): '.empty($tireqty).'<br />';

echo 'empty($nothere): '.empty($nothere).'<br />';

Refresh the page to see the results.

The variable $tireqty should return 1 (true) from isset() regardless of what value you entered in that form field and regardless of whether you entered a value at all. Whether it is empty() depends on what you entered in it.

The variable $nothere does not exist, so it generates a blank (false) result from isset() and a 1 (true) result from empty().

These functions are handy when you need to make sure that the user filled out the appropriate fields in the form.

Reinterpreting Variables

You can achieve the equivalent of casting a variable by calling a function. The following three functions can be useful for this task:

int intval(mixed var[, int base]);

float floatval(mixed var);

string strval(mixed var);

Each accepts a variable as input and returns the variable’s value converted to the appropriate type. The intval() function also allows you to specify the base for conversion when the variable to be converted is a string. (This way, you can convert, for example, hexadecimal strings to integers.)

Making Decisions with Conditionals

Control structures are the structures within a language that allow you to control the flow of execution through a program or script. You can group them into conditionals (or branching) structures and repetition structures (or loops).

If you want to sensibly respond to your users’ input, your code needs to be able to make decisions. The constructs that tell your program to make decisions are called conditionals.

if Statements

You can use an if statement to make a decision. You should give the if statement a condition to use. If the condition is true, the following block of code will be executed. Conditions in if statements must be surrounded by parentheses ().

For example, if a visitor orders no tires, no bottles of oil, and no spark plugs from Bob, it is probably because she accidentally clicked the Submit Order button before she had finished filling out the form. Rather than telling the visitor “Order processed,” the page could give her a more useful message.

When the visitor orders no items, you might like to say, “You did not order anything on the previous page!” You can do this easily by using the following if statement:

if( $totalqty == 0 )

echo 'You did not order anything on the previous page!<br />';

The condition you are using here is $totalqty == 0. Remember that the equals operator (==) behaves differently from the assignment operator (=).

The condition $totalqty == 0 will be true if $totalqty is equal to zero. If $totalqty is not equal to zero, the condition will be false. When the condition is true, the echo statement will be executed.

Code Blocks

Often you may have more than one statement you want executed according to the actions of a conditional statement such as if. You can group a number of statements together as a block. To declare a block, you enclose it in curly braces:

if ($totalqty == 0) {

echo '<p style="color:red">';

echo 'You did not order anything on the previous page!';

echo '</p>';

}

The three lines enclosed in curly braces are now a block of code. When the condition is true, all three lines are executed. When the condition is false, all three lines are ignored.

else Statements

You may often need to decide not only whether you want an action performed, but also which of a set of possible actions you want performed.

An else statement allows you to define an alternative action to be taken when the condition in an if statement is false. Say you want to warn Bob’s customers when they do not order anything. On the other hand, if they do make an order, instead of a warning, you want to show them what they ordered.

If you rearrange the code and add an else statement, you can display either a warning or a summary:

if ($totalqty == 0) {

echo "You did not order anything on the previous page!<br />";

} else {

echo $tireqty." tires<br />";

echo $oilqty." bottles of oil<br />";

echo $sparkqty." spark plugs<br />";

}

You can build more complicated logical processes by nesting if statements within each other. In the following code, the summary will be displayed only if the condition $totalqty == 0 is true, and each line in the summary will be displayed only if its own condition is met:

if ($totalqty == 0) {

echo "You did not order anything on the previous page!<br />";

} else {

if ($tireqty > 0)

echo $tireqty." tires<br />";

if ($oilqty > 0)

echo $oilqty." bottles of oil<br />";

if ($sparkqty > 0)

echo $sparkqty." spark plugs<br />";

}

elseif Statements

For many of the decisions you make, you have more than two options. You can create a sequence of many options using the elseif statement, which is a combination of an else and an if statement. When you provide a sequence of conditions, the program can check each until it finds one that is true.

Bob provides a discount for large orders of tires. The discount scheme works like this:

![]() Fewer than 10 tires purchased—No discount

Fewer than 10 tires purchased—No discount

![]() 10–49 tires purchased—5% discount

10–49 tires purchased—5% discount

![]() 50–99 tires purchased—10% discount

50–99 tires purchased—10% discount

![]() 100 or more tires purchased—15% discount

100 or more tires purchased—15% discount

You can create code to calculate the discount using conditions and if and elseif statements. In this case, you need to use the AND operator (&&) to combine two conditions into one:

if ($tireqty < 10) {

$discount = 0;

} elseif (($tireqty >= 10) && ($tireqty <= 49)) {

$discount = 5;

} elseif (($tireqty >= 50) && ($tireqty <= 99)) {

$discount = 10;

} elseif ($tireqty >= 100) {

$discount = 15;

}

Note that you are free to type elseif or else if—versions with or without a space are both correct.

If you are going to write a cascading set of elseif statements, you should be aware that only one of the blocks or statements will be executed. It did not matter in this example because all the conditions were mutually exclusive; only one can be true at a time. If you write conditions in a way that more than one could be true at the same time, only the block or statement following the first true condition will be executed.

switch Statements

The switch statement works in a similar way to the if statement, but it allows the condition to take more than two values. In an if statement, the condition can be either true or false. In a switch statement, the condition can take any number of different values, as long as it evaluates to a simple type (integer, string, or float). You need to provide a case statement to handle each value you want to react to and, optionally, a default case to handle any that you do not provide a specific case statement for.

Bob wants to know what forms of advertising are working for him, so you can add a question to the order form. Insert this HTML into the order form, and the form will resemble Figure 1.6:

<tr>

<td>How did you find Bob’s?</td>

<td><select name="find">

<option value = "a">I’m a regular customer</option>

<option value = "b">TV advertising</option>

<option value = "c">Phone directory</option>

<option value = "d">Word of mouth</option>

</select>

</td>

</tr>

Figure 1.6 The order form now asks visitors how they found Bob’s Auto Parts.

This HTML code adds a new form variable (called find) whose value will either be 'a', 'b', 'c', or 'd'. You could handle this new variable with a series of if and elseif statements like this:

if ($find == "a") {

echo "<p>Regular customer.</p>";

} elseif ($find == "b") {

echo "<p>Customer referred by TV advert.</p>";

} elseif ($find == "c") {

echo "<p>Customer referred by phone directory.</p>";

} elseif ($find == "d") {

echo "<p>Customer referred by word of mouth.</p>";

} else {

echo "<p>We do not know how this customer found us.</p>";

}

Alternatively, you could write a switch statement:

switch($find) {

case "a" :

echo "<p>Regular customer.</p>";

break;

case "b" :

echo "<p>Customer referred by TV advert.</p>";

break;

case "c" :

echo "<p>Customer referred by phone directory.</p>";

break;

case "d" :

echo "<p>Customer referred by word of mouth.</p>";

break;

default :

echo "<p>We do not know how this customer found us.</p>";

break;

}

(Note that both of these examples assume you have extracted $find from the $_POST array.)

The switch statement behaves somewhat differently from an if or elseif statement. An if statement affects only one statement unless you deliberately use curly braces to create a block of statements. A switch statement behaves in the opposite way. When a case statement in a switch is activated, PHP executes statements until it reaches a break statement. Without break statements, a switch would execute all the code following the case that was true. When a break statement is reached, the next line of code after the switch statement is executed.

Comparing the Different Conditionals

If you are not familiar with the statements described in the preceding sections, you might be asking, “Which one is the best?”

That is not really a question we can answer. There is nothing that you can do with one or more else, elseif, or switch statements that you cannot do with a set of if statements. You should try to use whichever conditional will be most readable in your situation. You will acquire a feel for which suits different situations as you gain experience.

Repeating Actions Through Iteration

One thing that computers have always been very good at is automating repetitive tasks. If you need something done the same way a number of times, you can use a loop to repeat some parts of your program.

Bob wants a table displaying the freight cost that will be added to a customer’s order. With the courier Bob uses, the cost of freight depends on the distance the parcel is being shipped. This cost can be worked out with a simple formula.

You want the freight table to resemble the table in Figure 1.7.

Figure 1.7 This table shows the cost of freight as distance increases.

Listing 1.2 shows the HTML that displays this table. You can see that it is long and repetitive.

Listing 1.2 freight.html—HTML for Bob’s Freight Table

<html>

<body>

<table border="0" cellpadding="3">

<tr>

<td bgcolor="#CCCCCC" align="center">Distance</td>

<td bgcolor="#CCCCCC" align="center">Cost</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="right">50</td>

<td align="right">5</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="right">100</td>

<td align="right">10</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="right">150</td>

<td align="right">15</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="right">200</td>

<td align="right">20</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="right">250</td>

<td align="right">25</td>

</tr>

</table>

</body>

</html>

Rather than requiring an easily bored human—who must be paid for his time—to type the HTML, having a cheap and tireless computer do it would be helpful.

Loop statements tell PHP to execute a statement or block repeatedly.

while Loops

The simplest kind of loop in PHP is the while loop. Like an if statement, it relies on a condition. The difference between a while loop and an if statement is that an if statement executes the code that follows it only once if the condition is true. A while loop executes the block repeatedly for as long as the condition is true.

You generally use a while loop when you don’t know how many iterations will be required to make the condition true. If you require a fixed number of iterations, consider using a for loop.

The basic structure of a while loop is

while( condition ) expression;

The following while loop will display the numbers from 1 to 5:

$num = 1;

while ($num <= 5 ){

echo $num."<br />";

$num++;

}

At the beginning of each iteration, the condition is tested. If the condition is false, the block will not be executed and the loop will end. The next statement after the loop will then be executed.

You can use a while loop to do something more useful, such as display the repetitive freight table in Figure 1.7. Listing 1.3 uses a while loop to generate the freight table.

Listing 1.3 freight.php—Generating Bob’s Freight Table with PHP

<html>

<body>

<table border="0" cellpadding="3">

<tr>

<td bgcolor="#CCCCCC" align="center">Distance</td>

<td bgcolor="#CCCCCC" align="center">Cost</td>

</tr>

<?

$distance = 50;

while ($distance <= 250) {

echo "<tr>

<td align="right">".$distance."</td>

<td align="right">".($distance / 10)."</td>

</tr>

";

$distance += 50;

}

?>

</table>

</body>

</html>

To make the HTML generated by the script readable, you need to include newlines and spaces. As already mentioned, browsers ignore this whitespace, but it is important for human readers. You often need to look at the HTML if your output is not what you were seeking.

In Listing 1.3, you can see

inside some of the strings. When inside a double-quoted string, this character sequence represents a newline character.

for and foreach Loops

The way that you used the while loops in the preceding section is very common. You set a counter to begin with. Before each iteration, you test the counter in a condition. And at the end of each iteration, you modify the counter.

You can write this style of loop in a more compact form by using a for loop. The basic structure of a for loop is

for( expression1; condition; expression2)

expression3;

![]()

expression1 is executed once at the start. Here, you usually set the initial value of a counter.

![]() The

The condition expression is tested before each iteration. If the expression returns false, iteration stops. Here, you usually test the counter against a limit.

![]()

expression2 is executed at the end of each iteration. Here, you usually adjust the value of the counter.

![]()

expression3 is executed once per iteration. This expression is usually a block of code and contains the bulk of the loop code.

You can rewrite the while loop example in Listing 1.3 as a for loop. In this case, the PHP code becomes

<?php

for ($distance = 50; $distance <= 250; $distance += 50) {

echo "<tr>

<td align="right">".$distance."</td>

<td align="right">".($distance / 10)."</td>

</tr>

";}

?>

Both the while and for versions are functionally identical. The for loop is somewhat more compact, saving two lines.

Both these loop types are equivalent; neither is better or worse than the other. In a given situation, you can use whichever you find more intuitive.

As a side note, you can combine variable variables with a for loop to iterate through a series of repetitive form fields. If, for example, you have form fields with names such as name1, name2, name3, and so on, you can process them like this:

for ($i=1; $i <= $numnames; $i++){

$temp= "name$i";

echo $$temp.'<br />'; // or whatever processing you want to do

}

By dynamically creating the names of the variables, you can access each of the fields in turn.

As well as the for loop, there is a foreach loop, designed specifically for use with arrays. We discuss how to use it in Chapter 3.

do…while Loops

The final loop type we describe behaves slightly differently. The general structure of a do…while statement is

do

expression;

while( condition );

A do..while loop differs from a while loop because the condition is tested at the end. This means that in a do…while loop, the statement or block within the loop is always executed at least once.

Even if you consider this example in which the condition will be false at the start and can never become true, the loop will be executed once before checking the condition and ending:

$num = 100;

do{

echo $num."<br />";

}while ($num < 1 ) ;

Breaking Out of a Control Structure or Script

If you want to stop executing a piece of code, you can choose from three approaches, depending on the effect you are trying to achieve.

If you want to stop executing a loop, you can use the break statement as previously discussed in the section on switch. If you use the break statement in a loop, execution of the script will continue at the next line of the script after the loop.

If you want to jump to the next loop iteration, you can instead use the continue statement.

If you want to finish executing the entire PHP script, you can use exit. This approach is typically useful when you are performing error checking. For example, you could modify the earlier example as follows:

if($totalqty == 0){

echo "You did not order anything on the previous page!<br />";

exit;

}

The call to exit stops PHP from executing the remainder of the script.

Employing Alternative Control Structure Syntax

For all the control structures we have looked at, there is an alternative form of syntax. It consists of replacing the opening brace ({) with a colon (:) and the closing brace with a new keyword, which will be endif, endswitch, endwhile, endfor, or endforeach, depending on which control structure is being used. No alternative syntax is available for do…while loops.

if ($totalqty == 0) {

echo "You did not order anything on the previous page!<br />";

exit;

}

could be converted to this alternative syntax using the keywords if and endif:

if ($totalqty == 0) :

echo "You did not order anything on the previous page!<br />";

exit;

endif;

Using declare

One other control structure in PHP, the declare structure, is not used as frequently in day-to-day coding as the other constructs. The general form of this control structure is as follows:

declare (directive)

{

// block

}

This structure is used to set execution directives for the block of code—that is, rules about how the following code is to be run. Currently, only one execution directive, called ticks, has been implemented. You set it by inserting the directive ticks=n. It allows you to run a specific function every n lines of code inside the code block, which is principally useful for profiling and debugging.

The declare control structure is mentioned here only for completeness. We consider some examples showing how to use tick functions in Chapters 25, “Using PHP and MySQL for Large Projects,” and 26, “Debugging.”

Next

Now you know how to receive and manipulate the customer’s order. In the next chapter, you learn how to store the order so that it can be retrieved and fulfilled later.