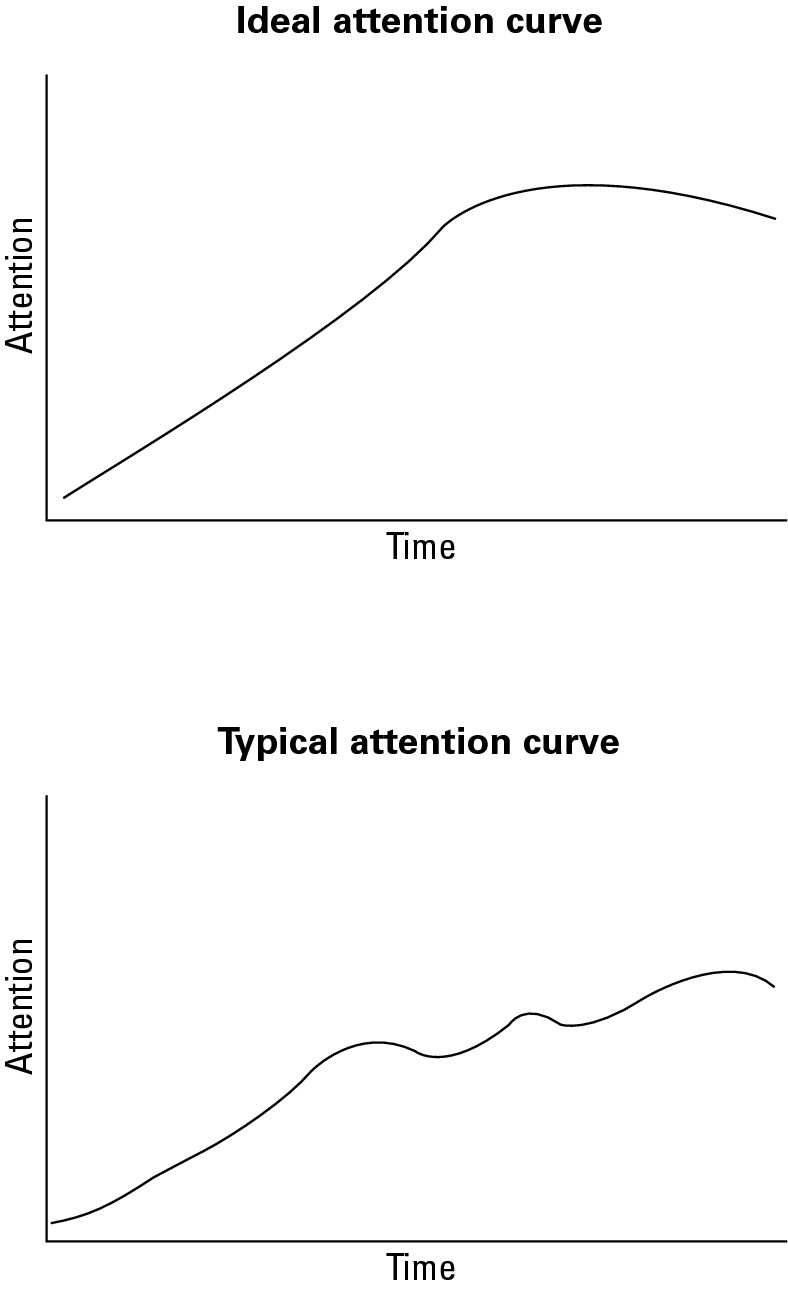

Figure 8-1: Visualising the ebb and flow of attention helps you stay focused on the outcome.

Chapter 8

Gaining and Maintaining Your Audience’s Interest

In This Chapter

![]() Attracting and maintaining interest

Attracting and maintaining interest

![]() Planning ahead with the attention curve

Planning ahead with the attention curve

![]() Dealing with lapses in attention

Dealing with lapses in attention

When was the last time someone mesmerised you to the point that you couldn’t take your eyes off her? What did she do that persuaded you to sit up and pay attention? How did she get you on board and keep you there? In other words, how did she grab your attention and hold it?

Engaging with your listeners so they’re open to what you say is vital if you’re going to persuade them to your way of thinking. Whether you want to gain and keep the attention of one or a hundred people, if you don’t connect from the beginning and increase their interest throughout, you’re going to have a hard time influencing them.

Fortunately, the ability to gain and keep someone’s attention involves simple strategies that you can apply to a variety of situations. Like all new skills, you have to practise if you want to hone your abilities.

In this chapter I share some ideas and concepts that equip you with an arsenal of techniques and tools to draw on when you want to persuade your audience – whether it’s one person, a small group of individuals or a cast of thousands – to move from where they are to where you want them to be. The result? You capture their attention, increase its intensity it and win them over to your idea or suggestion.

Getting Others to Notice You

Getting noticed has always been a challenge, and the twenty-first century hasn’t made the process any easier. With the shortage of time and a never-ending cascade of ideas and choices bombarding people daily, gaining and keeping someone’s attention is an on-going struggle.

The moment people see or hear you, they’re noticing you. They’re deciding whether they want to bother with you or not. To get yourself noticed, what you say and how you say it must be remarkable – so different, shocking or fresh that people are unable to ignore it.

Auditioning like a diva

According to theatre lore, when Barbra Streisand was still an unknown actress she walked into an audition visibly chewing a large wad of chewing gum. As she took her place on stage, she continued chomping, then stopped and with an embarrassed and coquettish smile, removed the gum from her mouth, stuck it under the stool on which she was sitting, and began singing again. After the auditions were over and all the performers had left the theatre, the show’s director walked onto the stage and looked underneath the stool, only to find nothing there. By having faked chewing gum and making a meal out of getting rid of it, Streisand managed to stand out from the crowd. While the story may or may not be true, getting noticed and sustaining interest is a cunning strategy.

Garnering a first glance

First impressions count, and you have between four and six seconds to get yourself noticed. Without a doubt, you’re competing with factors such as time constraints, fatigue, boredom and external noise – like ringing phones, crying babies and loud music – in your efforts to capture your listener’s attention.

Grabbing attention online and offline

With the plethora of online competitors vying for attention, how you come across determines whether you’re noticed or not. In a recent study of open rates, 51 per cent of the 4 million participants who were sent a data-driven email deleted the message within two seconds of opening it.

To capture and sustain attention, you need to have a great opening line that piques, pushes and prods your reader to open your email and read on. The same is true for websites. Research into motivation reveals that humans share three basic characteristics: curiosity, controversy and scarcity. Mix those with focusing on the three core goals that most people have – either making or saving time, money and energy – and you’re onto a winner.

Here are some examples of headlines that cater to people’s basic instincts and make them want to read on:

How to make £1,500 a week without leaving your home.

How to save thousands on your utility bills.

How to make him/her fall in love with you again.

How to lose those unsightly, unwanted pounds fast.

How to get published in 30 days or less.

Whether you’re writing copy or delivering a spoken message face-to-face or over the phone, the principle of appealing to people’s fundamental characteristics and core goals remains the same.

Identifying what matters to your audience

Everyone has more commitments and less time to focus on any one thing than they’d like. That’s why your message must be clear, compelling and concise. However you’re conveying your message – in writing or via audio recording, video or speaking directly to a live audience – adopt the following principles:

![]() Turn the complex into simple key points. Start by thinking about the big picture. Consider what is important about your message, the benefits, who it affects and how. What do you want your audience to do as a result of what you’ve communicated?

Turn the complex into simple key points. Start by thinking about the big picture. Consider what is important about your message, the benefits, who it affects and how. What do you want your audience to do as a result of what you’ve communicated?

![]() Appeal to your audience’s emotions, needs and desires. Back up your message with compelling evidence such as a single scintillating factoid or anecdotes that capture the emotional seriousness of the subject. While the evidence you choose to support your points will change depending on your audience, having all forms at the ready means you’re prepared for anything that comes your way. In addition, make your message memorable by including rhythm, contrast, metaphors and other rhetorical devices to make your message stick.

Appeal to your audience’s emotions, needs and desires. Back up your message with compelling evidence such as a single scintillating factoid or anecdotes that capture the emotional seriousness of the subject. While the evidence you choose to support your points will change depending on your audience, having all forms at the ready means you’re prepared for anything that comes your way. In addition, make your message memorable by including rhythm, contrast, metaphors and other rhetorical devices to make your message stick.

![]() Stick to the point. Messages that ramble on with little focus confuse your audience, leaving them wondering what you want from them.

Stick to the point. Messages that ramble on with little focus confuse your audience, leaving them wondering what you want from them.

Whether advertisers are persuading you to shop at certain stores, purchase particular products or travel to distant lands, they’re capturing your attention by appealing to your interests, fantasies or values – and often a combination of the three. Check out these examples:

![]() An offer of 50 per cent off sounds good when money’s in short supply. Here the advertiser is making a direct appeal to the buyers’ interests by proposing to save them money. (See the side bar ‘Grabbing attention online and offline’ above for more about appealing to human interests.)

An offer of 50 per cent off sounds good when money’s in short supply. Here the advertiser is making a direct appeal to the buyers’ interests by proposing to save them money. (See the side bar ‘Grabbing attention online and offline’ above for more about appealing to human interests.)

![]() An image of beautiful people drinking pina coladas on a sandy beach, and the suggestion of jasmine wafting on a balmy breeze is a pretty persuasive way to appeal to your fantasies and tempt you to a holiday when you’re shivering under a mountain of blankets or scraping ice off your car.

An image of beautiful people drinking pina coladas on a sandy beach, and the suggestion of jasmine wafting on a balmy breeze is a pretty persuasive way to appeal to your fantasies and tempt you to a holiday when you’re shivering under a mountain of blankets or scraping ice off your car.

![]() A good-looking doctor suggesting you take your cough syrup is more likely to influence your choices than a grumpy old man shoving the bottle at you. Even when you know the doctor in an ad is an actor, the advertisers still gain your attention by combining good looks and authority while tapping into your health needs. Here you’ve got fantasies – the good-looking doctor – as well as interests and values – your health – working in combination. For more about attractiveness and authority as persuasive tools, see Chapter 10.

A good-looking doctor suggesting you take your cough syrup is more likely to influence your choices than a grumpy old man shoving the bottle at you. Even when you know the doctor in an ad is an actor, the advertisers still gain your attention by combining good looks and authority while tapping into your health needs. Here you’ve got fantasies – the good-looking doctor – as well as interests and values – your health – working in combination. For more about attractiveness and authority as persuasive tools, see Chapter 10.

To gain your listeners’ attention, find out what matters to them. Do your homework to understand their issues and concerns so when the time comes to gain their attention, you can demonstrate that you’re already familiar with what’s important to them. Whether your homework takes the form of market research, asking people who personally know your listeners, or asking your listeners directly, the more you know about the people you’re planning to persuade – the more you know about their interests and issues – the more persuasive you’re able to be. However you gather your information, make sure you’re behaving in an appropriate, ethical manner. For more about ethical behaviour turn to Chapter 5.

Building up your energy and enthusiasm

You want to speak with enough confidence to demonstrate that you know what you’re talking about, without appearing arrogant. Practise some of the techniques below to build up your energy and enthusiasm:

![]() Smile. Whether you’re speaking to a large audience, a small gathering or just one person, before you say a word, smile. According to numerous studies, smiling suggests trustworthiness, cooperation, lifts moods and provides bursts of insight. Use your smiles selectively, as smiling at upsetting things can make you appear uncaring.

Smile. Whether you’re speaking to a large audience, a small gathering or just one person, before you say a word, smile. According to numerous studies, smiling suggests trustworthiness, cooperation, lifts moods and provides bursts of insight. Use your smiles selectively, as smiling at upsetting things can make you appear uncaring.

![]() Take care of yourself. Look after your body by eating the right foods, getting enough rest and exercising on a regular basis. Take time to socialise with friends and reflect on what’s important to you. Like any instrument, your body and mind perform better when you look after them. Refer to Chapter 2 for more about self-reflection.

Take care of yourself. Look after your body by eating the right foods, getting enough rest and exercising on a regular basis. Take time to socialise with friends and reflect on what’s important to you. Like any instrument, your body and mind perform better when you look after them. Refer to Chapter 2 for more about self-reflection.

![]() Plunge in. Long before Nike coined the slogan ‘Just do it’, Dale Carnegie said ‘Inaction breeds doubt and fear. Action creates confidence and courage. Fear evaporates when we take action.’ Commit to what you’re doing and watch your energy and enthusiasm rise.

Plunge in. Long before Nike coined the slogan ‘Just do it’, Dale Carnegie said ‘Inaction breeds doubt and fear. Action creates confidence and courage. Fear evaporates when we take action.’ Commit to what you’re doing and watch your energy and enthusiasm rise.

![]() Ask questions. Direct and rhetorical questions turn a monologue into a conversation as your listener becomes actively involved.

Ask questions. Direct and rhetorical questions turn a monologue into a conversation as your listener becomes actively involved.

![]() Use props. Relevant props that are visible and colourful help your listener remember what you’re talking about.

Use props. Relevant props that are visible and colourful help your listener remember what you’re talking about.

![]() Add drama. Bring what you’re saying to life by putting your voice and body into the process. Don’t be afraid to act out part of your speech, using your body as a prop and including dialogue, accents and vocal variety.

Add drama. Bring what you’re saying to life by putting your voice and body into the process. Don’t be afraid to act out part of your speech, using your body as a prop and including dialogue, accents and vocal variety.

![]() Tell a story. Facts tell, stories sell. Tell stories from your personal experience to develop your point. Include case studies and examples to make your material come alive.

Tell a story. Facts tell, stories sell. Tell stories from your personal experience to develop your point. Include case studies and examples to make your material come alive.

![]() Pause. If you pause you show confidence and your audience become curious about what’s coming next.

Pause. If you pause you show confidence and your audience become curious about what’s coming next.

Using hooks

![]() Anecdotes. People still pay attention to compelling, well-told stories. Tell a short personal story that connects you to your listeners and the issues at hand. Some people like to start their stories with the end, while others like to start at the very beginning. Whichever approach you take, make sure your story is relevant to your subject.

Anecdotes. People still pay attention to compelling, well-told stories. Tell a short personal story that connects you to your listeners and the issues at hand. Some people like to start their stories with the end, while others like to start at the very beginning. Whichever approach you take, make sure your story is relevant to your subject.

![]() Humour. Smiling makes people feel good, and laughter binds people together. Start off with a humorous spin on your topic, making sure your wittiness is appropriate to your message. I’m not suggesting that you try to be a stand-up comic, rather I encourage you to share a funny story about yourself or something that happened to reveal your charm. If you do tell a joke and it falls flat, don’t push harder. Drop it and move on.

Humour. Smiling makes people feel good, and laughter binds people together. Start off with a humorous spin on your topic, making sure your wittiness is appropriate to your message. I’m not suggesting that you try to be a stand-up comic, rather I encourage you to share a funny story about yourself or something that happened to reveal your charm. If you do tell a joke and it falls flat, don’t push harder. Drop it and move on.

![]() Statements that create doubt or disbelief. What you say doesn’t have to be true as long as you pique your listeners’ curiosity. A statement such as ‘What you’re about to hear will change your life forever’ may not be factually true but it may make your audience sit up in hope.

Statements that create doubt or disbelief. What you say doesn’t have to be true as long as you pique your listeners’ curiosity. A statement such as ‘What you’re about to hear will change your life forever’ may not be factually true but it may make your audience sit up in hope.

![]() Outstanding facts or statistics. Cite accurate information that’s interesting, relevant and not common knowledge.

Outstanding facts or statistics. Cite accurate information that’s interesting, relevant and not common knowledge.

![]() Opinions. Say something contrary to public opinion – such as, ‘I see nothing wrong with sweatshop labour practices’ – and watch the feathers fly. Your listeners are likely to stay engaged just to see what happens next.

Opinions. Say something contrary to public opinion – such as, ‘I see nothing wrong with sweatshop labour practices’ – and watch the feathers fly. Your listeners are likely to stay engaged just to see what happens next.

![]() Current events. Whether they skim the headlines while waiting for their lattés, catch a bit of the news while driving home from work, or follow sports and current affairs rigorously, most people have some knowledge of something that’s been happening in the world.

Current events. Whether they skim the headlines while waiting for their lattés, catch a bit of the news while driving home from work, or follow sports and current affairs rigorously, most people have some knowledge of something that’s been happening in the world.

![]() Quotes. They don’t have to be from famous people, just appropriate and timely.

Quotes. They don’t have to be from famous people, just appropriate and timely.

![]() Theatrics. As a former actor, I’m prone to add a bit of show business into my openings in order to gain the listeners’ attention. After you stumble over your opening lines or begin addressing your remarks to the wrong audience, your listeners will want to see what’s coming next. Give it a go as a new approach. Practise first to make sure your choices work.

Theatrics. As a former actor, I’m prone to add a bit of show business into my openings in order to gain the listeners’ attention. After you stumble over your opening lines or begin addressing your remarks to the wrong audience, your listeners will want to see what’s coming next. Give it a go as a new approach. Practise first to make sure your choices work.

Taking an interest in others

For most people, life is a case of ‘It’s all about me’. But guess what? No matter how charming and intelligent you are, no matter how creative your solutions or how logical your conclusions, if you don’t take into consideration the needs and wants of the people you want to influence, or if your product or idea isn’t relevant to them, you can’t expect to persuade them to adopt your way of seeing things.

Except for people who have something to hide, most people like it when others take an interest in them, because it makes them feel special. And if you make someone feel special, she’s much more likely to like you. See Chapter 10 for more on how liking and being liked are part of the persuasion process.

You can capture people’s attention by knowing what matters to them and showing that you care. Show your interest in others by exploring any of the following, either by directly asking or doing a bit of research first:

![]() Where they’re from. Every town, city and country has unique characteristics that influence people’s thinking and behaviour. Showing you’re interested in others’ backgrounds shows you’re interested in them as people.

Where they’re from. Every town, city and country has unique characteristics that influence people’s thinking and behaviour. Showing you’re interested in others’ backgrounds shows you’re interested in them as people.

![]() What matters to them. If you don’t already know, ask them what their concerns and issues are – and then respond with useful, relevant information. For example, are they concerned about the environment, taxes or government decisions? Do health and safety issues matter to them? Do they have children, pets, second homes? Touch on these pertinent topics and you tap into other people’s beliefs, values and concerns. And when you do that, you’re well on your way to capturing their attention.

What matters to them. If you don’t already know, ask them what their concerns and issues are – and then respond with useful, relevant information. For example, are they concerned about the environment, taxes or government decisions? Do health and safety issues matter to them? Do they have children, pets, second homes? Touch on these pertinent topics and you tap into other people’s beliefs, values and concerns. And when you do that, you’re well on your way to capturing their attention.

![]() What interests them. Golf, tennis, mountain climbing? Family, travel, fast cars? The more you know about your listeners, the better position you’re in to persuade them to pay attention.

What interests them. Golf, tennis, mountain climbing? Family, travel, fast cars? The more you know about your listeners, the better position you’re in to persuade them to pay attention.

![]() What they fear or are concerned about. What drives them and keeps them going? By knowing possible answers to their questions and solutions to their problems, you have a blueprint for influencing their decisions.

What they fear or are concerned about. What drives them and keeps them going? By knowing possible answers to their questions and solutions to their problems, you have a blueprint for influencing their decisions.

If you’ve experienced the phenomenon of someone showing interest in you, you probably enjoyed it. Perhaps someone touched on something that truly matters to you in the course of conversation. Or maybe you discovered that two of you share an experience or passion. These small connections make you more receptive to the other person. The energy flows between the two of you rather than in just one direction. You’re more likely to persuade – or be persuaded.

If you’re speaking to an audience of more than one or a few, the challenge of discovering everyone’s interests, needs and concerns may seem overwhelming. You may even find that some of the people’s interests are in conflict. That said, you can always count on people having interests around well-being, including financial, physical, spiritual or family. Turn to Chapter 2 for more on human concerns and motivations.

Using names

Addressing people by their names commands their attention. Remembering people as individuals and recalling something personal about them only furthers your connection. I find the best way to remember someone’s name is to repeat the name as soon as I’ve heard it and refer to the person by name during the conversation. For example, ‘It’s a pleasure to meet you, James’ and, later in the conversation, saying something like, ‘So tell me, James, how did you discover you and Ben both had a passion for extreme sports?’ You can find lots of tips for remembering names in Improving Your Memory For Dummies by John B Arden (Wiley).

Utilising key words

When you want to capture someone’s attention, choose your words carefully. Because of time constraints and information overload, people are selective in what they hear. While you’re speaking, everyone else has additional dialogues running through their heads. Did I pay before leaving the car park? Should I sell my shares in this business? What time is my daughter’s school play?

In order to bring your listeners’ attention back to you, find and use key words that spark their interest. Key words are clear, powerful words that appeal to your listeners’ emotions, curiosity and concerns. When you listen carefully to what people say, you can pick out the words that are key for them. For example, if someone talks about connection, passion, beliefs and values you know that those are buzz words you can incorporate into your presentation. When you incorporate key words early on (and, indeed, throughout your presentation) you stand a better chance of persuading your listeners than if your phrasing is haphazard. For example:

![]() Statement without key words: ‘Today I’m here to talk to you about how to make a good presentation.’

Statement without key words: ‘Today I’m here to talk to you about how to make a good presentation.’

![]() Statement strategically packed with key words: ‘If you want to connect with your audience, engage with their beliefs and values, and are passionate about convincing them to follow your lead, you’ve come to the right place.’

Statement strategically packed with key words: ‘If you want to connect with your audience, engage with their beliefs and values, and are passionate about convincing them to follow your lead, you’ve come to the right place.’

Connecting visually

Eye contact is a vital element in both capturing and maintaining your listeners’ interest.

Unless avoiding eye contact is part of your theatrical attention-grabbing opening (see the ‘Using hooks’ section earlier in this chapter), keep your head out of your papers and look at your audience before saying a word. And if looking anywhere other than at your audience is part of your ploy to gain their attention, let them know sooner rather than later why you’re behaving that way.

![]() In a group setting, spend about three seconds with each audience member, connecting visually and maintaining engagement. Scan the room as if you were talking to a group of interested friends rather than an amorphous gathering of indifferent individuals. While some extol the virtues of letting your eyes wander around the table or down one row and back up the next, I encourage you to take in the whole group before you begin speaking and then direct your comments to individuals in different parts of the room, working from one corner to the next in an M, W or X pattern. The important point is to make sure that you connect with all areas.

In a group setting, spend about three seconds with each audience member, connecting visually and maintaining engagement. Scan the room as if you were talking to a group of interested friends rather than an amorphous gathering of indifferent individuals. While some extol the virtues of letting your eyes wander around the table or down one row and back up the next, I encourage you to take in the whole group before you begin speaking and then direct your comments to individuals in different parts of the room, working from one corner to the next in an M, W or X pattern. The important point is to make sure that you connect with all areas.

![]() In one-to-one settings, look at the person you’re speaking to 45 to 65 per cent of the time. When you’re listening, increase your visual connection, looking at the speaker 60 to 85 per cent of the time.

In one-to-one settings, look at the person you’re speaking to 45 to 65 per cent of the time. When you’re listening, increase your visual connection, looking at the speaker 60 to 85 per cent of the time.

Only when you get to the ‘big ask’ – ‘When will you answer my question/sign this contract/pick up your room?’ – should you look your listener straight in the eye and not blink or back off until you’ve won your point.

When you look someone in the eye as you’re speaking to her, you come across as credible. And credible people carry authority. Refer to Chapters 5 and 11 for more information about the impact of authority and credibility on persuading and influencing.

Maintaining and Escalating Their Attention

Having garnered your audience’s attention and established your willingness to listen with all the techniques I cover in the preceding section, you now want to keep them engaged.

Actors, public speakers and people in sales know the importance of maintaining audience interest. Having gained your listeners’ attention, you must aim to lift your listeners’ interest for as long as possible and prevent it from collapsing, all the while competing with distractions (see the later section ‘Dealing with distractions’).

Speaking the same language

Capturing and maintaining your listeners’ attention requires that you pay attention to them. Observe how they communicate – what kinds of words and phrases they employ – and reflect back what you notice. This approach is similar to my advice in Chapter 7 where I suggest that you reflect back the words and gestures you observe.

Speaking the same language as your listeners improves your persuasive powers. I don’t mean you have to speak French to the French and Russian to the Russians in order to get them to understand you. (Of course, being able to speak the language of your clients and colleagues is helpful when doing business in a global world, and I encourage you to learn as many languages as you can.)

When you speak the same language as your audience, you reflect back what you hear and repeat similar words and phrases (see the earlier ‘Utilising key words’ section) and you further tailor your presentation to your listeners’ styles and preferences. For example,

![]() If you’re speaking to a group of people who are fact or logic driven, present your case in a logical, factual style. Base your remarks on reason to draw a conclusion. Because the basis of logical thinking is sequential thought, give structure to your presentation by arranging important ideas, facts and conclusions in a chain-like progression.

If you’re speaking to a group of people who are fact or logic driven, present your case in a logical, factual style. Base your remarks on reason to draw a conclusion. Because the basis of logical thinking is sequential thought, give structure to your presentation by arranging important ideas, facts and conclusions in a chain-like progression.

![]() If your listeners’ style is casual, loosen your verbal reins and reflect other people’s words and phrasing in yours. For example, casual speech is usually associated with people who you are close to and trust, and is the language used between friends, family and people who are similar to you. Casual language sounds friendly and tends to use contractions and simplified grammar. In presentations, you would tend to rely less on graphs, charts and hard data and more on anecdotal evidence.

If your listeners’ style is casual, loosen your verbal reins and reflect other people’s words and phrasing in yours. For example, casual speech is usually associated with people who you are close to and trust, and is the language used between friends, family and people who are similar to you. Casual language sounds friendly and tends to use contractions and simplified grammar. In presentations, you would tend to rely less on graphs, charts and hard data and more on anecdotal evidence.

You can pick up loads of information about various learning styles and information-gathering preferences in Neuro-Linguistic Programming For Dummies by Romilla Ready and Kate Burton (Wiley) as well as in Business NLP For Dummies by Lynne Cooper (Wiley). In addition, you can flip to Chapter 9 now to pick up tips for recognising how your listener prefers to make decisions.

Throughout this book I encourage you to match and pace your listeners in order to influence them. You can find further information and details about this process in both Business NLP For Dummies as well as in Neuro-Linguistic Programming For Dummies.

Painting word pictures

Creating emotional word pictures is one of the most powerful ways of maintaining your listeners’ attention. Great orators like Martin Luther King Jr, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, John F Kennedy, Socrates and numerous religious prophets understood how to link words and emotions to open hearts and minds.

Word pictures are so powerful because they tap into people’s values, beliefs, hopes and dreams. They ignite passion and enhance the vision. As I describe in Chapter 3, when you connect at an emotional level, your chances of persuading and influencing others’ choices increase.

Follow these suggestions to create successful and emotional word pictures:

![]() Make your picture relevant to the time and circumstances. For example, ‘The current economic climate has me feeling like I’m on a runaway coach with no seatbelts or driver at the wheel.’

Make your picture relevant to the time and circumstances. For example, ‘The current economic climate has me feeling like I’m on a runaway coach with no seatbelts or driver at the wheel.’

![]() Take into account your audience’s interests, passions or hobbies. If you’re describing to your golfing buddy how you envision a smooth leadership transition, you could say, ‘It’s like hitting a 200-metre drive straight down the fairway with a slow back swing and a full follow-through.’

Take into account your audience’s interests, passions or hobbies. If you’re describing to your golfing buddy how you envision a smooth leadership transition, you could say, ‘It’s like hitting a 200-metre drive straight down the fairway with a slow back swing and a full follow-through.’

![]() Rely on sources that are proven successes. You don’t need to reinvent the wheel here, just keep an eye open for interesting things that share similarities with points you want to make. Pay attention to recent events, historical happenings, familiar objects and natural phenomena.

Rely on sources that are proven successes. You don’t need to reinvent the wheel here, just keep an eye open for interesting things that share similarities with points you want to make. Pay attention to recent events, historical happenings, familiar objects and natural phenomena.

![]() Go for brevity. Try to paint your picture in two or three sentences.

Go for brevity. Try to paint your picture in two or three sentences.

![]() Rehearse your word pictures before putting them into practice. Share your ideas with a co-worker or friend before using them on the intended audience. See how they respond and ask for feedback.

Rehearse your word pictures before putting them into practice. Share your ideas with a co-worker or friend before using them on the intended audience. See how they respond and ask for feedback.

![]() Be selective and limit the number of images you use. While tried-and-tested word pictures such as ‘snug as a bug in a rug’, ‘dancing for joy’ and ‘walking with a spring in her step’ are evocative, they’re not original. See what range of images you can come up with. If you’re using word pictures in a five-minute presentation, limit them to no more than three and stick with a theme. Any more and you begin to sound forced and too clever for your own good. When you add too many different word pictures, your audience becomes confused as to what point you’re trying to make.

Be selective and limit the number of images you use. While tried-and-tested word pictures such as ‘snug as a bug in a rug’, ‘dancing for joy’ and ‘walking with a spring in her step’ are evocative, they’re not original. See what range of images you can come up with. If you’re using word pictures in a five-minute presentation, limit them to no more than three and stick with a theme. Any more and you begin to sound forced and too clever for your own good. When you add too many different word pictures, your audience becomes confused as to what point you’re trying to make.

Repeating yourself effectively

Make your information relevant to your listeners and repeat your message to persuade them to continue to pay attention to you. Clear, confident delivery and pertinent information ensure your listeners don’t drift off on an inner journey from lack of interest. See the ‘Addressing lapses in attention’ and ‘Dealing with distractions’ sections later in this chapter for more on effective repetition.

Maintain your listeners’ attention amid the repetition by varying your tone of voice (see Chapter 14), injecting unexpected words and phrases and throwing a view visuals into the mix.

Going with the Flow: Your Listeners’ Attention Curve

I’m willing to bet, and I’m not a betting woman, that at some point during a presentation, conversation or interview you were distracted by something that had nothing to do with the discussion at hand. Don’t worry. It happens to everyone.

Hopefully, you were paying attention at some point during the interaction and were able get back on board, picking up where you left off without too much difficulty or disruption. (Of course, if you weren’t interested in the first place, you’ll continue to struggle to pay attention.)

Recognising the signs that concentration is faltering is the first step to responding. Signs of lost attention include:

![]() Dull expressions and glassy-eyed stares

Dull expressions and glassy-eyed stares

![]() Little or no steady eye contact

Little or no steady eye contact

![]() Talking

Talking

![]() Tapping the desk with a pen or jiggling a foot with impatience

Tapping the desk with a pen or jiggling a foot with impatience

![]() Obvious attempts to change the subject

Obvious attempts to change the subject

![]() Silence and yawning

Silence and yawning

![]() Focussing on fingernails

Focussing on fingernails

![]() Doodling

Doodling

![]() Using technology, for example when emailing, texting and making phone calls

Using technology, for example when emailing, texting and making phone calls

Picturing peaks and troughs

A useful tool for dealing with people’s propensity to drift is to think of attention as following a pattern – in this case, the attention curve. While this model is now well-established and accepted, it appears to have originated in the 1940s with the Dutch chess master and psychologist, Adriaan de Groot, who based his theory on the thought processes of chess players. It was originally referred to as the memory model.

As Figure 8-1 shows, the ideal attention curve rises sharply at the beginning and continues on a gentle upward trajectory until the end of your presentation. While this experience sounds nice, don’t count on it happening in the real world.

Figure 8-1 also shows the more typical attention curve, in which attention rises and falls in waves periodically.

As long as you gain your listeners’ attention at the beginning and grab it again at the end, you have more of a chance of persuading them than if you start off on the back foot and finish up drifting off.

Putting the curve to good use

By visualising where you are in the conversation, staying on track becomes a simple matter of making the most of a particular moment along the attention curve. Rather like a surfboarder riding the big barrel, you can ride the curve and pay attention to the peaks and troughs. Even if you encounter a wipe-out-threatening wave, you can still land on your feet.

When a trough appears, figure out what’s happening. Are you droning, mumbling or speaking jargonese? Or did your listener not understand your point? Because you can’t sit in your listener’s head, you’ve got to be alert to the tell-tale signs of flagging attention and respond quickly when concentration wanes. Some tell-tale signs you may encounter include:

![]() Rotating the head from side to side as if the listener has cramp in her neck

Rotating the head from side to side as if the listener has cramp in her neck

![]() Narrowed eyes with her head turned away from you

Narrowed eyes with her head turned away from you

![]() Eyes glazed over

Eyes glazed over

![]() Shuffling feet, rubbing the ears, eyes or nose while turning slightly away from you

Shuffling feet, rubbing the ears, eyes or nose while turning slightly away from you

![]() Picking at her clothes and removing link only she can see, or looking around the room

Picking at her clothes and removing link only she can see, or looking around the room

![]() Clenched fists with tightened facial muscles

Clenched fists with tightened facial muscles

Addressing lapses in attention

Too often, people fail to notice when someone’s attention lapses. When you’re initiating a conversation or presentation, you are responsible for paying attention to your listener, picking up on the signals and responding appropriately.

You must get your point across on the first attempt. What happens after your first attempt influences what happens next. If someone rejects an idea up front, you’re going to struggle to change her mind later, even when she knows she’s wrong. Often pride steers this mind set because no one wants to be perceived as indecisive or incapable of making the right choice in the first place.

Never pitch your idea to someone whose attention is not focused on you. If you’re competing for attention from the beginning, wait until the person’s eyes, ears and body are pointed in your direction. You may have to pause for several seconds until the other person realises what’s happening. Waiting for someone’s full attention can be uncomfortable, so breathe deeply to calm yourself and hang in there. If you can’t gain the other person’s complete attention, ask to defer the meeting until a more convenient time for her. Chapter 14 has some really good breathing exercises for steadying your nerves.

Dealing with distractions

Distractions abound. Because you can’t avoid distractions entirely, your best approach is to address them head-on, minimising potential distractions and correcting actual ones – as I explore further in the following sections.

Minimising potential distractions

Sometimes the very space where you’re meeting lends itself to distractions – a window that lets in too much sun or frames a busy view, a listener positioned towards an open doorway where people continually cross, and chairs that are placed in such a way the audience struggles to see you all make gaining and maintaining your listeners’ attention a challenge. If you can adjust these distractions in advance, do. Move chairs and close blinds. As I say in the preceding section, ask your listeners to turn off their electronic devices during your presentation. You’re asked to turn them off when you go to the theatre and the cinema. There’s no reason why you shouldn’t ask your listeners to do so when you’re presenting.

Remedying visual distractions

When you notice something that shifts attention away from you as presenter, deal with it immediately. (And by extension, help other presenters by assisting them as appropriate.) Visual distractions rarely resolve themselves. In fact, they often gain more attention when left unattended.

Whether you see a coffee stain on someone’s jacket or some loo paper stuck to a shoe, acknowledging the elephant in the room is usually enough to satisfy everyone’s curiosity and get the conversation back on track.

If you sense that something about you – your clothing, your hair or spinach on your teeth – is causing a distraction, ask your audience by saying something like, ‘I notice you seem to be having difficulty concentrating on what I’m saying. Is there something I should know about?’ This way you acknowledge what’s going on and can do something about it.

Recognising disagreement

Lapses in attention may occur when someone in the audience disagrees with what the presenter is saying. Pay attention to your audience’s movements and expressions. If your words are causing a negative reaction, engage the listener – or perhaps several listeners – in dialogue about the issue. Address your listeners’ concerns head-on and without confrontation. For example, you could say, ‘What do you think about what I’ve just said?’ or ‘There may be some of you who don’t agree with what I’ve just said. Speak up so we can hear all points of view.’ By offering your audience the chance to express their views you’re showing that you’re open to other opinions and are willing to take them into consideration.

Identify possible areas of disagreement and confusion and prepare responses before your presentation. Audiences appreciate speakers who deal with reservations openly and honestly. Planning ahead and responding straight away leaves you in a better position to regain their attention and interest. See Chapter 4 for more about dealing with doubts.

Curbing constant interruptions

When you’re speaking with someone and are interrupted over and over again, you can quickly become annoyed, while the other person becomes distracted. You can both forget where you are in the conversation or decide to cut an important discussion short.

Today’s office environments are more pressurised than ever. People have more responsibilities and fewer support systems. Modern offices often feature open floor plans with few doors and walls. Most people’s phones and mobile devices never stop ringing throughout the working day.

You must redress interruptions if you want to gain someone’s attention and keep it:

![]() If someone interrupts your meeting by walking in, you can assess the problem and evaluate its possible impact on your listener’s concentration. If the person has been invited to join the meeting, carry on. If it’s a matter of someone dropping off some papers for the person you’re speaking to, stop until she leaves. If your listener seems distracted by the interruption, ask if she’d like you to come back another time.

If someone interrupts your meeting by walking in, you can assess the problem and evaluate its possible impact on your listener’s concentration. If the person has been invited to join the meeting, carry on. If it’s a matter of someone dropping off some papers for the person you’re speaking to, stop until she leaves. If your listener seems distracted by the interruption, ask if she’d like you to come back another time.

![]() When phone or email interrupts your conversation, observe how the other person reacts physically and vocally. (Find out more about the effect of body language and voice when conveying messages in Chapters 13 and 14.) If the person you’re talking to seems distracted, ask whether she’d like you to leave and come back later. That way you’re showing respect and demonstrating that you’re paying attention. Turn to Chap-ter 7 for tips on responding to non-verbal behaviours.

When phone or email interrupts your conversation, observe how the other person reacts physically and vocally. (Find out more about the effect of body language and voice when conveying messages in Chapters 13 and 14.) If the person you’re talking to seems distracted, ask whether she’d like you to leave and come back later. That way you’re showing respect and demonstrating that you’re paying attention. Turn to Chap-ter 7 for tips on responding to non-verbal behaviours.

Unless the other person asks to curtail your meeting, go back to where you were before the interruption and quickly summarise what you were saying.

You may fear that you sound like a repetitive parrot. Rest assured, you don’t. People remember only a small portion of what they hear, so recapping your points helps to cement them in your listeners’ minds. Plus you’re helping others regain their attention and return to the discussion. As I remind attendees of my public speaking programmes, ‘summarise to crystallise’.

Regaining attention after a lapse

Distractions and attention lapses are predictable, inevitable and often beyond your control. The key is how effectively you deal with the lapse and how quickly you can bounce back and reclaim attention.

In order to acknowledge a distraction or attention lapse effectively and move on quickly:

![]() Remain positive. When a lapse in attention occurs, stop what you’re doing, maintain eye contact and acknowledge the distraction. Respond with respect and a positive outlook. If you adopt a punitive attitude, all you achieve is mutiny.

Remain positive. When a lapse in attention occurs, stop what you’re doing, maintain eye contact and acknowledge the distraction. Respond with respect and a positive outlook. If you adopt a punitive attitude, all you achieve is mutiny.

![]() Revisit your last high point. Visualise your attention curve and return to the last relevant peak point. Quickly summarise that last positive moment to rein your listeners back in. When your listeners are on an emotional high they’re inclined to pay attention to what you’re saying.

Revisit your last high point. Visualise your attention curve and return to the last relevant peak point. Quickly summarise that last positive moment to rein your listeners back in. When your listeners are on an emotional high they’re inclined to pay attention to what you’re saying.

![]() Block off distractions quickly. If someone’s phone rings during a meeting you’re leading and the person insists on taking the call, ask her to leave the room and hold your thought until she returns.

Block off distractions quickly. If someone’s phone rings during a meeting you’re leading and the person insists on taking the call, ask her to leave the room and hold your thought until she returns.

![]() Memorise where you left off. Make a note for yourself or highlight your place in your outline or presentation. You’re in charge of keeping tabs on the conversation, not your listener.

Memorise where you left off. Make a note for yourself or highlight your place in your outline or presentation. You’re in charge of keeping tabs on the conversation, not your listener.

![]() Make the most of down time. While someone is away dealing with a phone call or must-answer email, open up the room to questions and observations from anyone who remains. Ask them for feedback so far and engage them in a discussion. By using the time constructively and positively – rather than treating the disruption as problematic – you maintain control of the situation and keep your listeners on track.

Make the most of down time. While someone is away dealing with a phone call or must-answer email, open up the room to questions and observations from anyone who remains. Ask them for feedback so far and engage them in a discussion. By using the time constructively and positively – rather than treating the disruption as problematic – you maintain control of the situation and keep your listeners on track.

![]() Recap fast and move on. When a person returns after dealing with a distraction or interruption, cover what she missed, ask whether your recap makes sense and continue with the flow from where you left off.

Recap fast and move on. When a person returns after dealing with a distraction or interruption, cover what she missed, ask whether your recap makes sense and continue with the flow from where you left off.

![]() Get comfortable with repetition. Don’t worry about repeating information – it’s a good way to re-enforce your message. Most people absorb only 40 per cent of what they hear, so repetition is vital in making sure your message is retained.

Get comfortable with repetition. Don’t worry about repeating information – it’s a good way to re-enforce your message. Most people absorb only 40 per cent of what they hear, so repetition is vital in making sure your message is retained.

Avoid repeating just for the sake of repeating, which only serves as a break in the flow of your persuasive story. People can easily lose interest. You know when you’re repeating for the sake of repeating when you’re not prepared and you keep covering the same territory, adding nothing new to the conversation. While some journalists repeat themselves with great success – for example, ‘I’ve asked you 14 times to answer my question and I’m asking you again’ – if you keep going over the same issue without contributing an insight or a point for discussion, you risk having your credibility questioned. See Chapter 5 for tips on establishing your credibility.

Avoid repeating just for the sake of repeating, which only serves as a break in the flow of your persuasive story. People can easily lose interest. You know when you’re repeating for the sake of repeating when you’re not prepared and you keep covering the same territory, adding nothing new to the conversation. While some journalists repeat themselves with great success – for example, ‘I’ve asked you 14 times to answer my question and I’m asking you again’ – if you keep going over the same issue without contributing an insight or a point for discussion, you risk having your credibility questioned. See Chapter 5 for tips on establishing your credibility.

Their attention and interest reinstated, your audience can enjoy, understand and positively engage with you. And you’re well on the way to persuading them!

Maintaining the emotional high

As I say in Chapter 3, people make decisions based on emotions. People respond more positively when they’re emotionally engaged than they do when they couldn’t care less. Appealing to people’s emotions is more effective than appealing to logic, and goes a long way to convincing your listener to accept your proposal.

Emotional highs are those moments when you successfully transport your audience to a hyper-receptive level. They’re excited and willing to commit to your idea. Look for the following signs to tell whether someone’s on an emotional high and ready to commit to your proposal:

![]() Eye contact. The eyes are wide and bright, the pupils are enlarged and the person is looking directly at you.

Eye contact. The eyes are wide and bright, the pupils are enlarged and the person is looking directly at you.

![]() Nodding head. When the other person nods her head up and down she’s indicating she concurs with what you’re saying.

Nodding head. When the other person nods her head up and down she’s indicating she concurs with what you’re saying.

![]() Smiling. A smile shows that she’s ready to reach agreement.

Smiling. A smile shows that she’s ready to reach agreement.

![]() Leaning forward. This position signals that the person’s ready to get up and go with your proposal.

Leaning forward. This position signals that the person’s ready to get up and go with your proposal.

![]() Vocal variety. The person speaks more quickly and the voice tends to be higher than usual.

Vocal variety. The person speaks more quickly and the voice tends to be higher than usual.

![]() Muscle control. When the muscles are firm but mobile, they’re conveying positive energy.

Muscle control. When the muscles are firm but mobile, they’re conveying positive energy.

Once you’ve got your listener’s attention and have achieved that emotional high, strike while the iron’s hot. Pull out your pen and get her to sign on the dotted line. If you don’t have a contract with you, shake hands to seal the deal and get the paperwork in the post poste haste! In Chapter 9 you can find different approaches to take depending on your listeners’ preferred decision-making styles.

The average attention span of the typical listener is six to eight minutes at a time. If you question how much time this is, hold your breath and see how long it takes before you’re gasping for air. Six to eight minutes can feel like an eternity. In order to hold your listeners’ attention you must engage them in the process. Some techniques you can use to keep your audience with you include:

The average attention span of the typical listener is six to eight minutes at a time. If you question how much time this is, hold your breath and see how long it takes before you’re gasping for air. Six to eight minutes can feel like an eternity. In order to hold your listeners’ attention you must engage them in the process. Some techniques you can use to keep your audience with you include: When you want to persuade your audience to listen to what you have to say, get yourself a hook. A

When you want to persuade your audience to listen to what you have to say, get yourself a hook. A