Chapter 12

Appealing to Other People’s Drives, Needs and Desires

In This Chapter

![]() Figuring out what matters to your listeners

Figuring out what matters to your listeners

![]() Pushing emotional buttons

Pushing emotional buttons

![]() Having an open mind

Having an open mind

![]() Motivating others with goals

Motivating others with goals

You must tap into what interests, excites or means something to other people if you hope to get them to do what you want. Lighting someone’s fire, revving a person’s engines and engaging your listeners at the level where they chomp at the bit to do your bidding is fundamental to success whether you’re at work, home or at play. Mind you, I’m not saying this prospect is easy. Just fundamental.

Rather than coercing and compelling people to do what you want them to do, targeting their drives, needs and desires produces generally positive results and good feelings for all. In this chapter you discover how to couch your comments in ways that others can understand, appeal to your listeners’ ideals, work with people whose point of view is different from yours and build enthusiasm and commitment to compelling goals in difficult times.

Making the Most of Others’ Feelings

Emotions play a big part in how people respond to your requests. If you don’t strike the right chord with others’ values, moods and feelings, you stand little chance of getting them to agree to your agenda. See Chapter 3 for more on emotions.

Advertisers have long known that the more they can find out about what matters to consumers, the more success they have in affecting behaviour (in this case, getting people to buy their products). The same goes for you at work and when interacting with other groups. Knowing what inspires people, what’s important to them and what they can’t live without serves as a guide when the time comes to influence their beliefs and behaviours. For example, if you’re working with a group of young people who are keen to go into politics, provide them with an opportunity to meet government leaders as part of their curriculum, with the stipulation being that they must reach a certain standard of academic achievement in order for this meeting to happen.

The following sections provide you with tips on how to tap into people’s feelings to realise their goals, dreams and desires.

Rising to difficult challenges

Throughout your life, you’re going to face difficult challenges. Taking personal risks and persuading others to do so too may be one of the greatest challenges you face. When people see success as unlikely – and failure a surer bet – your job is to come up with the right approach to get them to take the plunge.

![]() Hold candid and honest discussions about the probability of success. Encourage others to talk candidly about their trepidations. Dig deep to discover their fears and anxieties. Let them unload. Ask them what they’re afraid of, what may be holding them back, or what’s the worst thing that may happen if they committed to tackling the situation. Enquire about a time when they rose to a difficult challenge, what happened and how they felt afterwards. To paraphrase Franklin D Roosevelt, when they explore their fears, they discover the only thing they have to fear is fear itself and that, rather than fail, they just may succeed.

Hold candid and honest discussions about the probability of success. Encourage others to talk candidly about their trepidations. Dig deep to discover their fears and anxieties. Let them unload. Ask them what they’re afraid of, what may be holding them back, or what’s the worst thing that may happen if they committed to tackling the situation. Enquire about a time when they rose to a difficult challenge, what happened and how they felt afterwards. To paraphrase Franklin D Roosevelt, when they explore their fears, they discover the only thing they have to fear is fear itself and that, rather than fail, they just may succeed.

![]() Make roles and responsibilities crystal clear. Many concerns that emerge during discussions are likely to deal with performance and how it may impact on their careers and the organisations. Help people understand what others expect of them and break the challenge down into achievable, step-by-step measures that they can accomplish. Describe what is expected and, together, put a plan in place for how they’re going to get there. Communicate constantly to help them stay on track.

Make roles and responsibilities crystal clear. Many concerns that emerge during discussions are likely to deal with performance and how it may impact on their careers and the organisations. Help people understand what others expect of them and break the challenge down into achievable, step-by-step measures that they can accomplish. Describe what is expected and, together, put a plan in place for how they’re going to get there. Communicate constantly to help them stay on track.

![]() Spread the risk. Encourage others to discuss where they see potential risks and assure them that they’re not alone. Arrange for support systems such as a mentor or additional resources when you can. Encourage them to consider potential difficulties and put plans in place to prevent these difficultues from happening. Let others know they’re supported and cared for.

Spread the risk. Encourage others to discuss where they see potential risks and assure them that they’re not alone. Arrange for support systems such as a mentor or additional resources when you can. Encourage them to consider potential difficulties and put plans in place to prevent these difficultues from happening. Let others know they’re supported and cared for.

![]() Provide visible and unconditional support regardless of the outcome. Keep encouraging people and reward them for their efforts. Even if they don’t meet this challenge, if you praise them for their efforts the next time a challenge comes up they may be more open and able to rise to it.

Provide visible and unconditional support regardless of the outcome. Keep encouraging people and reward them for their efforts. Even if they don’t meet this challenge, if you praise them for their efforts the next time a challenge comes up they may be more open and able to rise to it.

The preceding process takes time. You can’t just command someone to ‘talk candidly’ with you and then expect great results. And the follow-up steps require thought, care and concern on your part as well.

Desiring to make a difference

Influencing people with passion, vision and the willingness to put in the time and effort to realise their dreams is a lot easier than pushing and pulling along people who are more like rocks than rockets.

If you’re lucky enough to work with people who want to make a difference, my advice is simple: let them. Encourage them, trust them and support them as they seek to leave their legacy.

People who want to achieve something rare and remarkable, or even cool and groovy, are assets to any organisation. Appeal to their sense of greatness, offer them chances to make meaningful contributions – and watch in wonder as they rise to their own challenges. Reach out to their values (see Chapter 2), celebrate the gifts they bring and give them the opportunity to shine. As long as you don’t ask them to compromise their own standards and values, you should have little trouble persuading them to fulfil their desires. When you praise their efforts, encourage their talents and give them the support they need to contribute to the organisation – be it a family unit or a global conglomerate – everyone benefits.

When most healthy people have satisfied their need for food, shelter and a sense of belonging, they seek opportunities to fulfil further goals and aspirations . Whether they want to find a cure for cancer, organise a fabulous party or eradicate polio, when someone gives them an opportunity to use their talents and abilities to make a meaningful and lasting contribution and to achieve something rare and wonderful, they go for it. See Chapter 2 for more about satisfying needs and self-esteem.

Offering encouragement

Encouraging people is one of the greatest gifts you can give them. You’re not filling their minds with fantasy. You’re inspiring them to be themselves at their very best. For example:

![]() If someone thinks he has a winning idea that may be the next Microsoft, Apple or the solution to world hunger, encourage him to go for his goal. No matter if you think his idea is too farfetched. If he thinks he’s onto something, give him the chance to find out.

If someone thinks he has a winning idea that may be the next Microsoft, Apple or the solution to world hunger, encourage him to go for his goal. No matter if you think his idea is too farfetched. If he thinks he’s onto something, give him the chance to find out.

![]() If someone has a project to complete that he’s struggling with, giving a few cheers from the sidelines may be all he needs to become re-engaged with the task at hand.

If someone has a project to complete that he’s struggling with, giving a few cheers from the sidelines may be all he needs to become re-engaged with the task at hand.

Encouragement motivates people to strive for the difficult and to make continuous improvements in their performance. It enhances self-confidence and can make someone feel courageous when they’ve been feeling downhearted. Encouragement expands people’s visions and fosters a ‘can do’ attitude.

Strange as it may seem, even the most talented, capable and influential people sometimes need words of encouragement. No matter who you are and no matter how capable and talented you may be, I’m willing to venture that you’ve experienced times filled with self-doubt – times when you would have benefitted from the odd word of encouragement. The world can be dark and lonely at times. By encouraging people who are struggling, you validate their abilities and remind them of their strengths and talents.

Offering encouragement creates bonds between you and the person you’re supporting. They feel capable and compelled to respond positively to your support, knowing that you believe in them. They don’t want to let you down.

Furthermore, encouragement breeds encouragement. For example, when you encourage one of your team members to do his best, he’s likely to encourage others to do theirs. Positive energy leads to more positive energy.

Appreciating the relationship between individuals and groups

Many would-be persuaders mistakenly take a limited view of who they’re attempting to influence. They seek to understand the ins and outs of one key person and then wonder why their efforts to persuade fall flat.

Some people like to think that they’re a rock and an island, and in many ways they may be. That being said, the needs and desires of people whose opinion matters to them are still going to influence them.

Pay attention to the people who surround the person you want to influence. These trusted and informed people exist in all groups both at home and at work and influence your target’s behaviour. The person you’re aiming to persuade seeks their opinions, needs their advice and includes them in meetings. Not only are they channels of information, they also can put pressure on your target when a choice has to be made and they can reinforce the decision once everyone has agreed to it.

Knowing Who You’re Talking To

One size does not fit all when it comes to motivating, persuading and influencing people. What gets me up and going in the morning isn’t what persuades my beloved husband to flick back the duvet, bound out of bed and embrace the day. Or, as Paul Simon sang, ‘One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor’.

Some people are rational and orderly in their approach to life. To persuade these people, provide fine details in a structured style. Others prefer to think in terms of big pictures and get charged up when you present your case in terms of future possibilities. To persuade people who seek harmony in their relationships, present points of agreement and accord. The list of different types of people, all of whom have their unique view points and needs, would fill a book on its own. I have chosen to write about these three because they’re common types. Of course, you can argue that your family is filled with feisty, argumentative types or that you’ve yet to find a seeker of harmony at work. The point to remember from this chapter is that the more you understand what drives the people you live, work and engage with, the better able you are to address their needs and desires. The more you can accept and respond positively to what is important to them, the more success you can have in creating constructive, persuasive relationships. (Turn to Chapter 9 to gain further insight into people with different decision-making styles.)

Reading other people correctly and pushing the right buttons to influence their behaviour requires insight and finesse. Take the time to listen to what they say, watch how they work and reflect on what it all may mean. See Chapter 7 for more on effective listening.

Make listening to others and observing their behaviour part of your daily routine. It doesn’t matter where you are – at home, at the grocery store, on public transportation or in a shareholders meeting – practice your observation skills every time you get the chance. The more you notice about people, the more in tune you become with them and can adapt your persuasive powers to meet their needs and desires. Reflect back words and phrases people use and match their behaviours to gain rapport. As you establish rapport with other people, you’re better positioned to influence their thinking and behaviour. For further information about establishing rapport turn to Chapter 13. You can also refer to Neuro-lingustic Programming For Dummies by Romilla Ready and Kate Burton (Wiley), which covers rapport in detail.

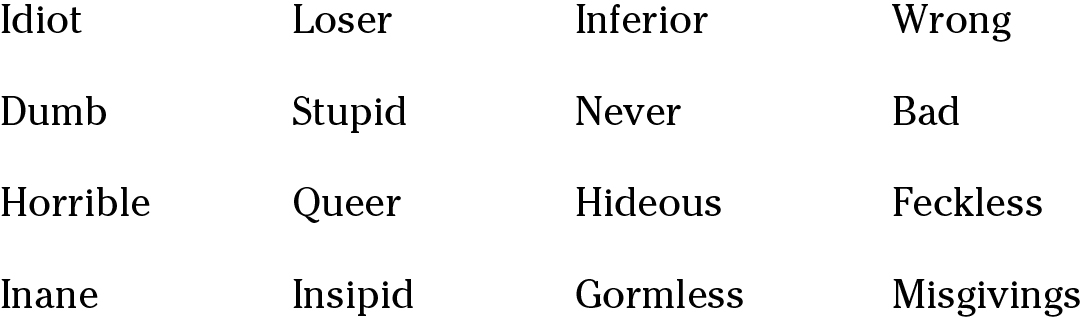

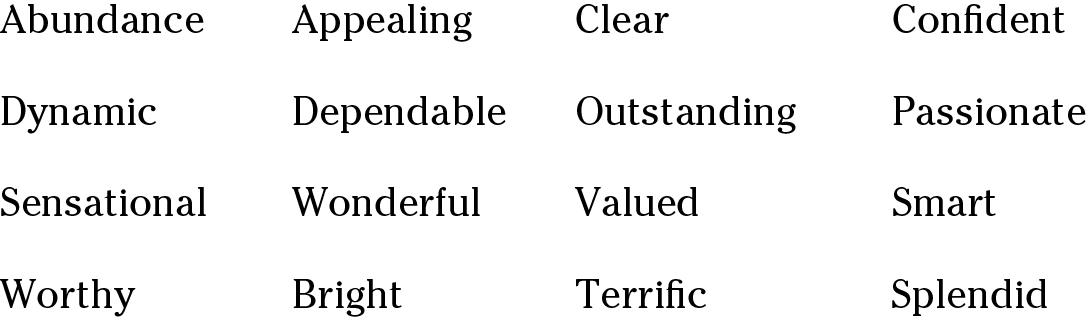

Listen to the language people use. If people pepper their speech with negative words, they likely want to control others and make them feel inferior. A partial list of negative words to listen out for may include:

On the other hand, people who fill their sentences with positive words tend to have an optimistic outlook and want to make people feel good. Examples of positive words include:

In addition to paying attention to what people say – their actual words – observe the way they speak and move. You can tell how someone’s feeling by the tone in their voice plus their posture, gestures and facial expressions. For example, some people speak quickly, with excitement and energy in their voices. You can tell from the high pitch and quick speed that they’re keyed up. Depending on the circumstances, this pitch and speed may mean that they’re agitated or happily animated. Other people lack variety or expression in their voices and tend to speak in a monotone. This kind of speech indicates that they’re emotionally uncommitted to what they’re saying. Some people speak in long sentences, wanting to hold the listener’s attention for as long as they can, while others rely on basic nouns and verbs to convey their message simply and quickly. For more information about how your body and voice impact on your ability to persuade and influence, turn to Chapters 13 and 14.

In addition to considering others’ beliefs and behaviours, take a closer look at your own. Get to know your style and then identify how it may or may not match the people you want to influence. The more you know about yourself, the better able you are to adapt your approach to get others to respond to your proposals and propositions. For more about understanding yourself and others, see Chapter 2.

For example, if your partner complains that you don’t give him enough of your time and attention, acknowledge his feelings and ask him how he’d like things to be. Allow him all the time he needs to talk through his feelings without interrupting him and refrain from judging or arguing with what he says(see Chapter 7 for tips on how to listen effectively). Once he’s finished speaking, you can respond by saying, ‘I understand what you’re saying about my not giving you enough of my time and attention and appreciate how you feel about that. How would you like things to be and what suggestions do you have for making things better? I’d like to make this work for both of us.’ By giving him a chance to express his emotions, demonstrating that you respect his feelings and engaging him in the process of improving the situation, you’ve opened the door to influencing the outcome and making things better. The following sections cover three common categories of people you’re likely to encounter and seek to influence. While many other types abound, I have chosen to concentrate on these three here as I kept coming across them during my research for this book, particularly in the Harvard Business Review on The Persuasive Leader (Harvard Business School Press).

If you’re serious about wanting to improve your ability to persuade and influence others, make it part of your daily routine to observe the different types of people you come across in your day-to-day life and reflect on how they respond to events and occurrences. The more you notice, the better prepared you become to adapt your style to meet theirs when the time comes to persuade them.

The types identified below are fairly easy to spot from their behaviours. Others are trickier as they can be a complicated blend of different styles. If you come across people you can’t immediately pin-point, refer to Chapter 2, where you can find tips for figuring out what drives different types of people.

Swaying the rational and orderly

Some people like a place for everything and everything in its place. They tend to make their decisions based on choices that lead to the best outcome for themselves, as opposed to what may be best for others. Guided by their intellect rather than their experiences or emotions, their behaviour is driven by a need for structure and orderliness and they reason in a clear and consistent manner. They often respond well to facing reality and moving forward to achieve clearly defined goals. In organisations, you frequently find accountants fit into this group, as do lawyers.

Persuading rational and orderly individuals requires a consistent, unswerving message. Rational and orderly people respond particularly well when you:

![]() Approach your interactions with openness, honesty and candour – particularly if tough challenges lie ahead. See Chapter 5 for more about acting with openness and honesty.

Approach your interactions with openness, honesty and candour – particularly if tough challenges lie ahead. See Chapter 5 for more about acting with openness and honesty.

![]() Set high aspirations for them to strive for. See the ‘Establishing Goals and Expectations’ section later in this chapter for much more on goal-setting. One of the highest aspirations people can face is honestly confronting and dealing with inescapable critical facts that they, and others, have made about their performance.

Set high aspirations for them to strive for. See the ‘Establishing Goals and Expectations’ section later in this chapter for much more on goal-setting. One of the highest aspirations people can face is honestly confronting and dealing with inescapable critical facts that they, and others, have made about their performance.

![]() Establish a step-by-step approach that takes them from where they are now to where you want them to be. Set guidelines and milestones that they can refer to as they head toward their goal.

Establish a step-by-step approach that takes them from where they are now to where you want them to be. Set guidelines and milestones that they can refer to as they head toward their goal.

![]() Encourage them along the way. See the ‘Providing incentives for successful results’ section later in this chapter.

Encourage them along the way. See the ‘Providing incentives for successful results’ section later in this chapter.

No matter what the make-up of your audience is, all groups benefit from clear communication. When organisations are in transition, as many businesses and other groups frequently are, stakeholders need to know where they’re going and how they’re going to get there. Quarterly updates, status reports and occasional emails aren’t enough to keep the fires burning. You must regularly repeat messages that remind employees of the company’s direction, encourage them to keep going and reassure them during uncertain times. With email, Twitter, Facebook, mobile devices and other tools at your disposal, you don’t have any excuse for not communicating.

You don’t need to go into the gritty detail. TMI – too much information – can overwhelm and confuse employees and other interested parties. Just stick with the basic message – your explanation of what’s happening, your expectations and your vision of what their future holds – and your ability to persuade people to follow your course escalates.

Persuading big picture visionaries

Look to see who’s coming up with innovative ideas and the chances are you’re looking at a big picture visionary. These people typically have a clear view of what they want to do and how they want to do it and serve organisations best during times of major transitions. In plays, novels and films, they’re the protagonist, the person to whom others look for leadership and advice. At work, they’re the ones who look around their organisations and see possibilities where others seen chaos and problems. Examples of big picture visionaries include Steve Jobs, the Google inventors Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Henry Ford, and, some may even say, Julian Assange, founder of Wikileaks.

Big picture visionaries are, the leaders of the pack in that they provide long-term direction and vision. They’re clear about what they want to do and adept at getting individuals to buy into their vision. They win people over because they take the time to understand what drives and motivates them. Rather than telling you what to do, visionaries appeal to your values (see Chapter 3) and then work to win you over by tying their vision to yours (see Chapter 4). While they work best working in partnership and create a shared sense of vision and meaning with others, they’re not always the most popular nor accepted members of an organisation because they tend not to be mainstream.

Big picture visionaries are the darlings of moviemakers because of their ability to win people over rather than telling them what to do. In Remember the Titans, Herman Boone (played by Denzel Washington) is a high school football coach. In one of the film’s most moving scenes, he explains why, in the American South during the early 1970s, uniting the black and white players on the football team is about much more than just sport, but rather treating people with respect and acting like men. If you want to listen to the speech go to www.americanrhetoric.com/MovieSpeeches/moviespeechrememberthetitans.html.

Instead, persuade these big picture people to do something you need by reflecting back their picture to them. Let them know that you understand what they’re striving for and what you need to achieve it. Pick up on their ideas and build on them. Visionaries make decisions quickly, even impulsively, focusing on ideas rather than details. Match their style and speak in broad, general terms about what can be rather than what is.

Big picture visionaries have little patience with minutiae and complex detail. They’re interested in future possibilities and don’t like being hampered by barriers or limits. More than wanting to know facts, which can bore them or make them impatient, they’re interested in implications and relationships. They’re stimulated by possibilities, seeking to create and share new ideas. If you tend to focus more on the here and now, adjust your view. Observe how these big picture people communicate, the way they think and the language they use. The more you can adapt your style to theirs, the more success you have in persuading them to see your point of view. In Chapter 9 I look at matching styles and how you can adapt your style to suit another person’s.

Big picture visionaries respond particularly well when you

![]() Provide a thumbnail sketch at the beginning of your remarks, focussing on long-term, future possibilities

Provide a thumbnail sketch at the beginning of your remarks, focussing on long-term, future possibilities

![]() Offer a reality check without discarding their ideas, helping them to link their visions to what’s real and actual

Offer a reality check without discarding their ideas, helping them to link their visions to what’s real and actual

![]() Suspend reality when necessary to brainstorm and generate ideas

Suspend reality when necessary to brainstorm and generate ideas

![]() Avoid getting bogged down in facts and details

Avoid getting bogged down in facts and details

For more about persuading people who see the big picture, turn to Chapter 9.

Influencing seekers of harmony

People who seek harmony want to feel connected to what they’re doing. They’re able to empathise and develop rapport easily with others, often seeing and appreciating others’ perspectives. Supportive, nurturing and interested in other people, they enjoy cooperating and collaborating, connecting with others and creating a harmonious environment. In addition, harmony seekers need to feel an interdependence with others, in which they’re mutually responsible to and share a common set of principles with others. They also seek personal influence and a sense of belonging to something larger than themselves. If you want to get the best from people who seek harmony, show them where they fit into the grand scheme of things. Show them their place and purpose and how their contribution impacts on the bigger picture.

People who seek harmony become alienated when they’re unsure of what’s expected of them, whether in family situations, within a working group, committee or larger organisation. Rather than performing with a sense of ‘you and me together’, a feeling of ‘them against me’ may arise, leading to negative behaviour that adversely affects the other people they’re engaged with as well as the overall goals of the project they’re working on.

People who seek harmony long to maintain balance and avoid disruption. They look for the best in people, are fundamentally optimistic about the future, and tend to have a calming and stabilising effect on their co-workers. They’re supportive, go with the flow, don’t worry about the small stuff and, as a rule, are pretty easy to work with, if you like that type of person.

When you’re influencing people who seek harmony:

![]() Encourage open communication. Support harmony-seeking people in expressing their views and ideas. Ask for feedback and provide meaningful, clearly defined and realistic goals.

Encourage open communication. Support harmony-seeking people in expressing their views and ideas. Ask for feedback and provide meaningful, clearly defined and realistic goals.

![]() Foster a good work/life balance. While you can rightly expect someone to give their all on the job, you get the best out of people when you recognise that they have lives outside the workplace. If you want something from them, make sure that you give them something back in return that meets their needs and relates to their values. The more you respect people’s issues away from work, the happier and more productive they are at work.

Foster a good work/life balance. While you can rightly expect someone to give their all on the job, you get the best out of people when you recognise that they have lives outside the workplace. If you want something from them, make sure that you give them something back in return that meets their needs and relates to their values. The more you respect people’s issues away from work, the happier and more productive they are at work.

![]() Provide platforms for personal development. Whether you offer in-house training, time out for study leave or tuition for external courses, providing such opportunities shows people that you care about them, which leads to their giving you their best.

Provide platforms for personal development. Whether you offer in-house training, time out for study leave or tuition for external courses, providing such opportunities shows people that you care about them, which leads to their giving you their best.

![]() Praise generously. Seekers of harmony respond well to positive feedback. And when they do slip up, point it out and move on. Conscientious people typically take on board feedback from their mistakes quickly.

Praise generously. Seekers of harmony respond well to positive feedback. And when they do slip up, point it out and move on. Conscientious people typically take on board feedback from their mistakes quickly.

![]() Pay attention to tone. While harmony seekers can deal with tough news and criticism, you need to use a soft, gentle voice when presenting it. Your message may even feel out of synch with your soft, warm voice when you’re talking with harmony-seekers. That okay. They’re typically conscientious and listening to everything you’re saying.

Pay attention to tone. While harmony seekers can deal with tough news and criticism, you need to use a soft, gentle voice when presenting it. Your message may even feel out of synch with your soft, warm voice when you’re talking with harmony-seekers. That okay. They’re typically conscientious and listening to everything you’re saying.

Cultivating an Unbiased View

The most persuasive people I know are able to stand outside of situations and look at them clearly and in an unbiased manner. The best persuaders embrace differences among people and look to find approaches that suit everyone. Turn to Chapter 5 to find out more about compromising and the process of giving-and-taking.

Whatever you do and whoever you are, when you want to persuade or influence another person, leave your biases at the gate. If you want to get someone to agree with your proposal, proposition, or simply your point of view, telling them they’re wrong to feel, think or behave the way they do is sure to scupper your plans when you go to persuade them to do something you want them to do.

If you force your views and values on people you want to influence, you’re likely to find yourself at the wrong end of the stick. In all my research for this book, I was unable to find any long-lasting successful examples of people persuading others to follow their lead by coming in with a heavy-handed approach. Oh, sure, you may be able to bludgeon others with your viewpoint and get them grudgingly to do your bidding. But they end up resenting you and don’t want to have anything to do with you again.

The following sections help you cultivate a neutral, unbiased attitude, which improves your ability to achieve good results in challenging situations.

Letting go of judgment

Being able to render sound judgement at appropriate moments is essential to being an effective persuader. However, when your judgments are condemnatory, self-righteous or constantly critical of another person’s worth, your point of view and ability to see a situation from all sides becomes skewed. People tend to disregard others who speak in judgmental terms because their comments have a ring of negativity about them.

Let go of thoughts and feelings like, ‘he’s so dumb . . .’ and ‘that’s so stupid . . .’ and ‘his idea will never work’. Replace them with positive outlooks. Earlier in this chapter, I provide lists of negative and positive words to help you understand the impact of language on your thoughts and behaviours. If you want to understand more about how substituting unhelpful thoughts and feelings with more positive ones, have a look at Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Dummies, by Rhena Branch and Rob Willson (Wiley) as well as Emotional Healing For Dummies by David Beales and Helen Whitten (Wiley) both of which cover the topic in detail and provide step-by-step activities.

I’m not suggesting that you become a Pollyanna figure – although positive, optimistic people do bring oomph and energy to their projects and are generally more fun to be around. Simply being neutral – or at least not negative – can be useful when you’re interacting with others. By demonstrating no bias for or against a proposition, you allow others to draw their own conclusions without being influenced by yours. See Chapter 7 for tips on remaining neutral when you’re listening.

Uncovering shared interests

Persuasive people are passionate people. They pursue and project their passions with enthusiasm, making themselves interesting and inviting to be around. When you’re around people like that, you want to follow their suggestions; especially when you find that you share similar interests or feel passionate about the same things. For more about how similarities can help you influence others, see Chapter 11.

Discover similar interests by doing any and all of the following:

![]() Believe that everyone has passions. Everyone feels passionate about something. Your job is to find out what the other person’s passions are. Sports, food, family and fashion are often fruitful places to start. If you’re up to the challenge, find out how they feel about politics or religion.

Believe that everyone has passions. Everyone feels passionate about something. Your job is to find out what the other person’s passions are. Sports, food, family and fashion are often fruitful places to start. If you’re up to the challenge, find out how they feel about politics or religion.

If you struggle to find any passion points, keep digging. Eventually, something will surface. But if it doesn’t, you may have to give up on that person as a lost cause.

![]() Take the attitude that you’ve something in common. If you think that you’ve something in common, you’ve a much better chance of finding it! Having a positive outlook gets you where you want to be faster than assuming that you share nothing in common.

Take the attitude that you’ve something in common. If you think that you’ve something in common, you’ve a much better chance of finding it! Having a positive outlook gets you where you want to be faster than assuming that you share nothing in common.

![]() Be diligent in your research. As long as you’ve got a computer, or at least access to one, you’ve little excuse for not being able to find out about the people you want to persuade. Between Google, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter, tons of useful information is out there. And if you can’t find out more about someone online, ask around.

Be diligent in your research. As long as you’ve got a computer, or at least access to one, you’ve little excuse for not being able to find out about the people you want to persuade. Between Google, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter, tons of useful information is out there. And if you can’t find out more about someone online, ask around.

![]() Take note of what you observe. You can find clues about people’s passions by looking around their homes, desks and offices. I’m not suggesting that you snoop, just that you observe. For example, if you notice a picture of a family skiing holiday and you’re a skier, you ask where the photo was taken and share a skiing story of your own. You can also find out about people’s passions by listening to what they say. (Turn to Chapter 7 for more about active listening skills. Chapter 2 is filled with tips for finding common points of interest.)

Take note of what you observe. You can find clues about people’s passions by looking around their homes, desks and offices. I’m not suggesting that you snoop, just that you observe. For example, if you notice a picture of a family skiing holiday and you’re a skier, you ask where the photo was taken and share a skiing story of your own. You can also find out about people’s passions by listening to what they say. (Turn to Chapter 7 for more about active listening skills. Chapter 2 is filled with tips for finding common points of interest.)

Establishing Goals and Expectations

Establishing clear goals and expectations is a powerful tool for persuading people. Compelling goals and expectations build on people’s drives, needs and desires – while encouraging worthwhile contributions to the entire organisation or a greater cause.

Imagine working without specific goals in place for a moment. Your daily life would be meaningless, chaotic and, quite frankly, a waste of time. Working in an environment where you’ve no purpose to your efforts would be enough to make you call in sick on a regular basis.

The following sections offer a quick course on how to set goals that inspire without being too easy and that motivate without being overwhelming.

Thinking SMART

For people in today’s working world, SMART is a five-letter word that comes up again and again when talking about goal-setting.

SMART is a handy acronym that highlights five key characteristics of any well-constructed goal. Every SMART goal is Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-bound.

![]() Specific: Without a specific goal, you don’t know what you’re aiming to accomplish. When you’re determining your goal, include what you specifically want to accomplish, who you may need to call on for help, by when you want to achieve your goal, your reasons, purpose or benefits for accomplishing your goal and potential requirements and constraints.

Specific: Without a specific goal, you don’t know what you’re aiming to accomplish. When you’re determining your goal, include what you specifically want to accomplish, who you may need to call on for help, by when you want to achieve your goal, your reasons, purpose or benefits for accomplishing your goal and potential requirements and constraints.

![]() Measurable: Put in place concrete criteria for measuring your progress. When you measure your progress, you’re more likely to stay on track, reach your targets and feel a sense of achievement that spurs you on to reach your ultimate goal. To confirm that your goal is measurable, ask questions such as How much? How many? And How do I know when I’ve met my criteria?

Measurable: Put in place concrete criteria for measuring your progress. When you measure your progress, you’re more likely to stay on track, reach your targets and feel a sense of achievement that spurs you on to reach your ultimate goal. To confirm that your goal is measurable, ask questions such as How much? How many? And How do I know when I’ve met my criteria?

![]() Attainable: Once you’ve identified goals that are most important to you, you figure out ways to make them happen. You develop the attitudes, skills and resources to reach them. When you plan your steps wisely and establish a time frame that allows you to carry out your steps, you can achieve your goal.

Attainable: Once you’ve identified goals that are most important to you, you figure out ways to make them happen. You develop the attitudes, skills and resources to reach them. When you plan your steps wisely and establish a time frame that allows you to carry out your steps, you can achieve your goal.

![]() Realistic: A realistic goal is one that you’re both willing and able to strive for. Only you can determine how high a goal you want to set for yourself. Be sure that whatever goal you establish has enough motivational force to keep you going. If you truly believe you can accomplish your goal, that goal is probably realistic. Measure it against anything similar that you’ve accomplished in the past. You can also ask yourself what conditions would have to exist in order for you to accomplish this goal.

Realistic: A realistic goal is one that you’re both willing and able to strive for. Only you can determine how high a goal you want to set for yourself. Be sure that whatever goal you establish has enough motivational force to keep you going. If you truly believe you can accomplish your goal, that goal is probably realistic. Measure it against anything similar that you’ve accomplished in the past. You can also ask yourself what conditions would have to exist in order for you to accomplish this goal.

![]() Timely: Ground your goal in a time frame. Without a deadline, you’ve no sense of urgency and you may let your goal drift on and on. With a definite date, you’ve set your unconscious mind in motion to begin working toward your desired outcome. (T can also stand for tangible. When you can experience your goal with one or more of your senses – touch, taste, sight or smell), you’ve a better chance of making it specific, measurable and therefore attainable.)

Timely: Ground your goal in a time frame. Without a deadline, you’ve no sense of urgency and you may let your goal drift on and on. With a definite date, you’ve set your unconscious mind in motion to begin working toward your desired outcome. (T can also stand for tangible. When you can experience your goal with one or more of your senses – touch, taste, sight or smell), you’ve a better chance of making it specific, measurable and therefore attainable.)

Making your goals clear

The secret to making your goals clear lies in the first two letters of SMART. You must make your goals specific and measurable, or quantifiable.

When you appeal to people’s needs and desires and let them know exactly what’s expected of them, they’re more likely to hop on board than when instructions are vague and ambiguous. When you include a clear-cut time frame for tasks to be completed, you enhance your ability to persuade others to follow your agenda.

Don’t waste your time telling someone to ‘try hard’ or ‘do your best’. Give them a specific target to shoot for, such as ‘aim to reduce your turnaround time by 40 per cent’ or ‘cut your costs by a third this next quarter’.

In addition to making your goals specific, make them challenging to achieve. Studies show that, when you present teams and individuals with specific and difficult goals, their performances are measurably better than when the goals are vague and easy.

If you set targets that are easily achieved, they’re not exciting. And if people aren’t excited about what they’re doing, they don’t tend to bother doing it. On the other hand, by setting high goals, people feel a great sense of accomplishment after they get there.

Ensuring that your goals are attainable

As I point out in the preceding section, stretching yourself to meet challenging aspirations is important in creating a sense of pride and fulfilment. However, you also need to make sure that the targets you set aren’t too challenging. Persuading someone to give their all when the person has no chance of crossing the finish line is pointless.

Set targets that strike a balance between challenging and realistic and watch people leap at the chance to attain them. If you set a goal that stands no chance of being met, your team becomes more demotivated than if you set a goal that was too easy to achieve. People have a strong need for achievement and success. Setting challenging and realistic goals is one way of persuading them to go for gold.

![]() Losing 10 pounds in 5 weeks and keeping them off for minimum of a year. At an average rate of 2 pounds per week, this goal is appropriately challenging. Losing 10 pounds in a week and keeping them off for at least a year is unrealistic.

Losing 10 pounds in 5 weeks and keeping them off for minimum of a year. At an average rate of 2 pounds per week, this goal is appropriately challenging. Losing 10 pounds in a week and keeping them off for at least a year is unrealistic.

![]() Becoming conversant in a foreign language in six months. If you attend classes regularly and practice daily, you should be able to converse within this time frame. Only giving yourself a week to go from non-speaker to conversant would be an unrealistic challenge.

Becoming conversant in a foreign language in six months. If you attend classes regularly and practice daily, you should be able to converse within this time frame. Only giving yourself a week to go from non-speaker to conversant would be an unrealistic challenge.

Providing incentives for successful results

You can persuade people to go to great lengths when you place a meaningful reward for them at the finish line. Whether you’re presented with a trophy, given a letter of commendation or a public pat on the back with a heartfelt ‘Thank you for your contribution’, research and real-life scenarios show that recognition and achievement are influencing factors in getting people to produce their best.

For the most part, the more difficult the goal, the greater the reward. You can persuade people to reach for the stars by assuring them that you intend to repay their efforts when they come up with the goods.

Gaining commitment

When setting goals, make sure that individuals understand and agree to them. If they don’t, everyone ends up frustrated and disappointed.

Avoid frustration and disappointment by getting people to help create their own goals. Involve individuals in setting goals, making decisions and being responsible for the outcome and watch their efforts increase.

The more difficult goals are to achieve, the more commitment they require. Easy goals are no-brainers and entail little effort. Tough goals demand that you dig deep to find inspiration and enticement.

While it would be unreasonable, pointless and a complete waste of resources to negotiate and gain approval for every goal a company or large organisation sets out, the goals you do persuade individuals to strive for need to be consistent and in harmony with previous expectations.

Strive to show that the goals you’re proposing are in the interests of the organisation and are consistent with stated aims. Also, let people know what’s happening throughout the organisation so that they can see that the proposed goals are consistent with the organisation’s overall strategy. Goals work best when they’re written down and signed by all relevant parties. Posting goals in a public spot – like the bulletin board in the break area or the home page on the company intranet site – reminds everyone of what they’ve agreed to do. At a personal level, write down your goals, sign and date them. Research shows that when you commit to goals in writing, you’re more likely to achieve them because the act of writing them down provokes and reminds you to take action.

Providing feedback

You may find it a lot easier to influence a person’s behaviour when you provide feedback to let them know how they’re doing along the way towards meeting the agreed goals and expectations. Checking-in on an informal and regular basis encourages people to keep going when times are tough and lets them know that you recognise and appreciate their efforts.

In addition to informal feedback, be sure to build informal sessions where you sit down face to face and discuss goal performance. Without providing specific and structured responses to people’s efforts, they don’t know where they stand. Expectations can be ignored, goals can be missed, and disappointment and resentment inevitably arise. If you want to influence others’ long-term performances and persuade them to take the necessary actions to meet their goals, take the time to provide them with feedback to keep them going, especially when times get tough.

‘You really messed up on that presentation. You were unorganised, lacking in confidence and didn’t know what you were talking about’

you probably won’t help matters; whereas if you say

‘You tried to cover a lot of material in a short amount of time. When you lost your place on your second point, you turned away from the audience and looked at your notes and the screen for the rest of your presentation. At the end, when you said, ‘Thank you’ you were looking at your notes. This behaviour disengaged you from your listeners. If you ever lose your place again, what can you do differently?’

you’re much more likely to produce positive results.

The adage ‘different strokes for different folks’ rings loud and clear when getting people to come on board with you. Although I do share a few reliable categories of motivation in this chapter, everyone is different, and you must do your own homework. Seek to know what drives someone to show up and do his best. Discover what he needs to convince him that your way is the best way. Dig deeper and uncover your audience’s innermost desires. Do all that, and you’re on the right track to creating friendly persuasion.

The adage ‘different strokes for different folks’ rings loud and clear when getting people to come on board with you. Although I do share a few reliable categories of motivation in this chapter, everyone is different, and you must do your own homework. Seek to know what drives someone to show up and do his best. Discover what he needs to convince him that your way is the best way. Dig deeper and uncover your audience’s innermost desires. Do all that, and you’re on the right track to creating friendly persuasion. Observe

Observe  The next time you see someone who needs encouragement, let them know how special they are. Instead of just flattering the person with nice words, respond to something specific he’s doing, such as the way he’s following through on leads, developing younger members of the team or adding value through his artistic talents. Highlight something about his character that you admire – or a positive difference you see in his performance. For example, saying something like, ‘I really appreciate the time and attention you take with our presentations. Even though you have to stick with the corporate template, you manage to make the slides look interesting and exciting.’ You can also say, ‘I really appreciate and admire the extra effort you put into your work. Your ‘stick-to-itiveness’ inspires me to apply myself more, too. Thank you.’

The next time you see someone who needs encouragement, let them know how special they are. Instead of just flattering the person with nice words, respond to something specific he’s doing, such as the way he’s following through on leads, developing younger members of the team or adding value through his artistic talents. Highlight something about his character that you admire – or a positive difference you see in his performance. For example, saying something like, ‘I really appreciate the time and attention you take with our presentations. Even though you have to stick with the corporate template, you manage to make the slides look interesting and exciting.’ You can also say, ‘I really appreciate and admire the extra effort you put into your work. Your ‘stick-to-itiveness’ inspires me to apply myself more, too. Thank you.’ When you’re influencing other people’s behaviour, don’t deliberately make them feel anxious (‘the result of the project may mean the life or death of this department!’) or ashamed (‘I expected more from someone with your level of education’). While both approaches can yield temporary gains, scared team members often get frozen in their fears, and shamed people slink away depressed or revolt. State your remarks positively (‘I know we can count on you to see this project through on time and on budget’) or (‘with your education and experience, you possess knowledge and insight that others don’t have’). See the section ‘Establishing Goals and Expectations’ later in this chapter.

When you’re influencing other people’s behaviour, don’t deliberately make them feel anxious (‘the result of the project may mean the life or death of this department!’) or ashamed (‘I expected more from someone with your level of education’). While both approaches can yield temporary gains, scared team members often get frozen in their fears, and shamed people slink away depressed or revolt. State your remarks positively (‘I know we can count on you to see this project through on time and on budget’) or (‘with your education and experience, you possess knowledge and insight that others don’t have’). See the section ‘Establishing Goals and Expectations’ later in this chapter. People who seek harmonious relationships tend to be reserved and focus on people and feelings. They support others and seek honest, open and friendly relationships. They’re tolerant and prefer a collaborative approach to establishing and maintaining harmony within a group. They can feel that others take advantage or ask too much of them. People whose styles are different from theirs may see them as people-pleasers who are constantly compromising for the sake of harmony.

People who seek harmonious relationships tend to be reserved and focus on people and feelings. They support others and seek honest, open and friendly relationships. They’re tolerant and prefer a collaborative approach to establishing and maintaining harmony within a group. They can feel that others take advantage or ask too much of them. People whose styles are different from theirs may see them as people-pleasers who are constantly compromising for the sake of harmony.