10

10

The quality of food

Food adulteration in the 1850s

In spite of the startling disclosures of the extent and seriousness of adulteration which had been made earlier in the century by Accum, Mitchell, Normandy, and other reliable observers, neither Parliament nor the nation was yet convinced that the problem was sufficient to warrant intervention by the state. Before 1850 it was still possible to have legitimate doubts – to believe that adulteration was not universal, but restricted to certain towns or, indeed, to certain parts of towns; that adulterations were not harmful, but, on the contrary, constituted improvements which lowered the cost of expensive foods to the poor; that most if not all sophistications were made in response to public taste and at the inconvenience of food manufacturers. The year 1850 marks a decisive turningpoint in public attitudes about such matters. After this only the deluded, the perverse, and the wicked could continue to defend adulteration or see it as anything except a major social, economic, and public health problem.

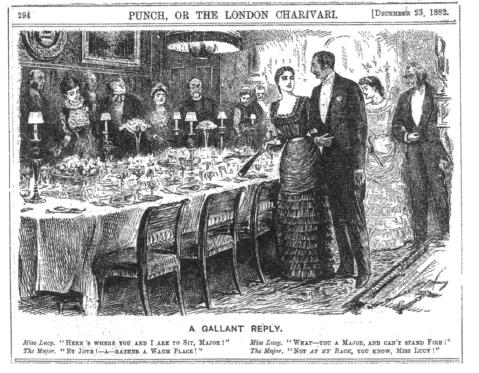

Late in that year Thomas Wakley, the radical doctor-editor of the Lancet who, as coroner for West Middlesex, had already earned a reputation for fearless exposures of workhouse scandals, decided to institute a thorough and searching investigation into the methods and extent of food adulteration. Dr Arthur Hassall, physician and lecturer on medicine at the Royal Free Hospital, was appointed to conduct the inquiry with the assistance of Henry Letheby, later to become Medical Officer of Health for the City of London: between 1851 and 1854, the journal printed each week their reports on every major article of food and drink, reports so voluminous that at the end of four years they were separately published in a bulky treatise for wider circulation.1 There were several new and distinctive features about what Punch described as ‘the Lancet’s detective force’. For one thing, the survey was the most rigorous and advanced series of tests to which foods had ever been subjected; in all, some 2,400 analyses were carried out, and Hassall was the first investigator to make extensive use of the microscope as an aid to detection. By its means many previously unknown frauds were revealed, and suspected ones confirmed. For another, Wakley took the bold step of publishing, after due warning, the names and addresses of manufacturers and traders whose samples were reported as impure. The complete accuracy of the analyses is confirmed by the fact that only one was ever challenged, and even this had to be withdrawn when the retailer discovered that his goods had in fact been adulterated without his knowledge.

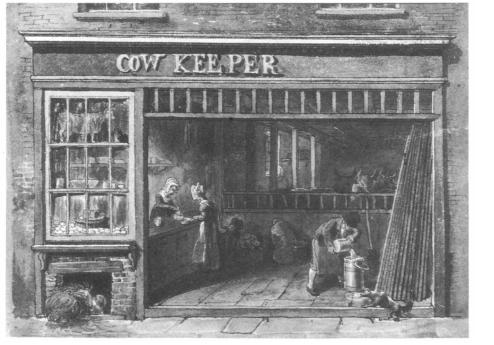

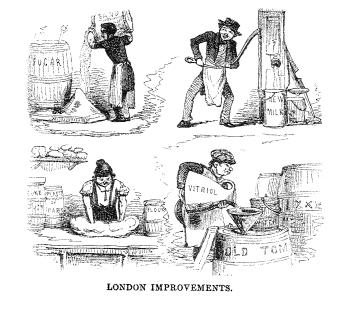

Hassall examined some thirty of the commonest foods, drinks, and condiments, and compiled detailed classifications showing the various adulterants used for giving weight and bulk, for imparting colour, and for simulating taste, smell, and other properties. His findings, based on personal analyses of samples obtained indiscriminately from hundreds of shops all over London, proved beyond doubt that serious, and often dangerous, adulteration existed of practically every food which it would pay to adulterate; moreover, by comparing his with the earlier investigations it seems clear that adulteration had grown steadily throughout the first half of the century, to reach peak proportions in the 1850s. By now it had become impossible to obtain several basic foods in a pure state. For example, every one of forty-nine random samples of bread which Hassall analysed contained alum, including loaves sold by the League Bread Company, which had advertised the ‘perfect purity’ of its bread in The Times and warranted it ‘free from alum and other pernicious ingredients’. In addition to this, half the samples of flour analysed by Hassall also contained alum, often unknown to the baker, so that in many cases bread was in fact receiving a double dose. In tea he found the leaves of sycamore, plum, and horsechestnut as well as exhausted tea-leaves, and concluded that ‘there is reason to believe that the manufacture of spurious tea, both black and green … prevails extensively at the present time’.2 Week by week the truth was uncovered. Oatmeal was cheapened with barley-meal and refuse known in the trade as ‘rubble’; milk had added water in amounts ranging from 10 to 50 per cent; of twenty-nine tins of coffee examined, twenty-eight were adulterated with chicory, mangel-wurzel, and acorn, while several also contained red oxide of lead derived from a ferruginous earth used as a colouring adulterant of the chicory. By such detailed analyses Hassall amply demonstrated what others had only suspected – that many adulterations were not merely frauds on the pocket but constituted serious hazards to health. Poisonous colouring matters, chiefly mineral dyes, were widely used for ‘facing’ tea and colouring preserved meats and fish, while sugar confectionery, eaten mainly by children, contained a truly appalling collection of them: of a hundred samples of sweets analysed, fifty-nine were coloured with chromate of lead, twelve with red lead, eleven with gamboge, eleven with Prussian and Antwerp blue, six with vermilion, fifteen with artificial ultramarine, ten with Brunswick green, and nine with arsenite of copper. Many samples contained no fewer than seven different colours and four poisons. In many the sugar itself had been adulterated with hydrated sulphate of lime, and in four cases the colours had been painted on with white lead.3

If they had remained as articles in a learned journal, it is doubtful whether even HassaH’s startling revelations would have achieved a very wide publicity. Fortunately, they were not only published in collected book form but, in popularized versions, were reprinted extensively in the daily press and periodical literature. The amount of public interest and concern was accurately expressed by one contributor to the Quarterly Review, who wrote:

A gun suddenly fired into a rookery could not cause a greater commotion than did the publication of the names of dishonest tradesmen; nor does the daylight, when you lift a stone, startle ugly and loathsome things more quickly than the pencil of light, streaming through a quarter-inch lens, surprised in their native ugliness the thousand and one illegal substances which enter more or less into every description of food which it will pay to adulterate.

The Lancet articles at last compelled public recognition of an urgent social problem, and brought its reform within the sphere of practical politics. Throughout 1855 and 1856 a Select Committee of the House of Commons heard detailed evidence from doctors, chemists, traders, and manufacturers which completely endorsed Hassall’s findings. Dr Alphonse Normandy, the author of a standard work on commercial products, summed up the position when he told the Committee: ‘Adulteration is a widespread evil which has invaded every branch of commerce; everything which can be mixed or adulterated or debased in any way is debased.’ The final report of the Committee, published in 1856, regretted that:

we cannot avoid the conclusion that adulteration widely prevails. Not only is the public health thus exposed to danger and pecuniary fraud committed on the whole community, but the public morality is tainted and the high commercial character of the country seriously lowered, both at home and in the eyes of foreign countries.4

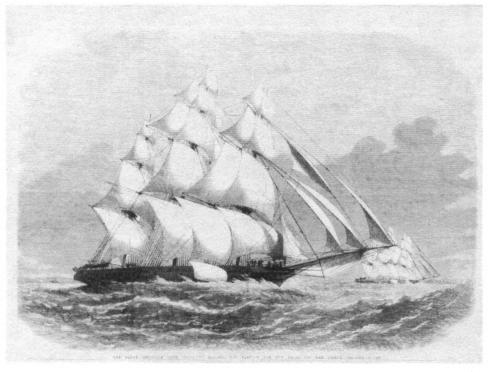

From the wide range of expert evidence which it took, the Committee of 1855–6 unearthed even more details of the methods and extent of adulteration than Hassall had been able to discover. Tea was one of the articles most heavily adulterated, both in China and after its arrival in England, and had been subjected to close examination by a chemist, Robert Warington:

Two samples of tea, a black and a green, were lately put into my hands by a merchant for examination, the results of which he has allowed me to make public. The black tea was styled scented caper; the green, gunpowder; and I understand they are usually imported into this country in small chests called catty packages. The appearance of these teas is remarkable. They are apparently exceedingly closely rolled, and very heavy, the reasons for which will be clearly demonstrated. They possess a very fragrant odour. The black tea is in compact granules, like shot of varying size, and presenting a fine, glossy lustre of a very black hue. The green is also granular and compact, and presents a bright pale-bluish aspect, with a shade of green, and so highly glazed and faced that the facing rises in clouds of dust when it is agitated or poured from one vessel to another; it even coats the vessels or paper on which it may be poured… . The greater part of the facing material was removed. It proved, in the case of the sample of green tea, to be a pale Prussian blue, a yellow vegetable colour which we now know to be turmeric, and a very large proportion of sulphate of lime. The facing from the sample of black tea was perfectly black in colour, and on examination was found to consist of earthy graphite, or black lead. It was observed that during the prolonged soaking operation to which these teas had been submitted, there was no tendency exhibited in either case to unroll or expand, for a reason which will be presently obvious. One of the samples was therefore treated with hot water, without, however, any portion of a leaf being rendered apparent. It increased in size, slightly, was disintegrated, and then it was found that a large quantity of sand and dirt had subsided (amounting to 37.5 per cent in the case of the black, and 45.5 per cent in the case of the green tea)… it was quite evident that there was no leaf to uncurl, the whole of the tea being in the form of dust. The question next presented itself as to how these materials had been held together, and this was readily solved; for on examining the infusion resulting from the original soaking of the sample, abundant evidence of gum was exhibited.5

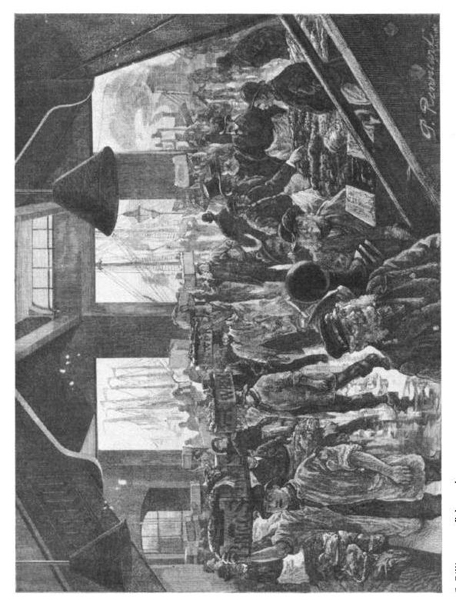

These spurious teas were known openly in China as ‘Lie flower caper’ and ‘Lie gunpowder’, and to the English broker under the more accurate description of ‘gum and dust’. They were bought by wholesale and retail dealers at from 8d to 1 s a pound for mixing with teas which would sell at 6s and more a pound. Other cases were quoted to the Committee of teas which contained nearly half their weight in iron filings, of leaves rolled up to imitate tea which were not tea at all, and of chests which contained bricks, iron, and other refuse. But perhaps more important because less easily detectable than these crude frauds, a large proportion of the expensive green teas sold in England – the Hysons, Souchongs, and gunpowders – were made from common and damaged green tea, and sometimes ordinary black tea, ‘treated’ in the Canton factories by colouring and glazing with mineral dyes; one experienced dealer, Joseph Woodin, estimated that at least half of all the green teas imported, representing between four and five million lb a year, were ‘Canton made’.6 Woodin was the man who had founded the Co-operative Central Agency and had had his chests of pure uncoloured tea rejected by societies in the north and midlands because they looked less attractive than the highly coloured green teas generally sold there. Fortunately, Woodin persevered. Lecturers were employed by the agency to go round the country and explain adulteration to the working classes; some at least were convinced, and sales gradually mounted.7 But in the 1850s domestic adulteration by dyeing with dangerous colouring matters, the use of noxious ‘tea improvers’, and the mixing of damaged and spoiled teas with gum, sand, and other undesirable substances were all extensively carried on, and in May 1851, Londoners were alarmed to discover that the manufacture of completely spurious tea had not yet been suppressed. The Times reported that Edward South and his wife Louisa, of Camberwell, had been discovered

busily engaged in the manufacture. There was an extensive furnace before which was suspended an iron pan containing sloe-leaves, and tea-leaves which they were in the habit of purchasing from coffee-shop keepers after being used. On searching the place they found an immense quantity of used tea, bay-leaves and every description of spurious ingredients for the purpose of manufacturing illicit tea, and they were mixed with a solution of gums and a quantity of copperas… . The prisoners had pursued their nefarious trade most extensively, and were in the habit of dealing largely with grocers, chandlers and others, especially in the country… .8

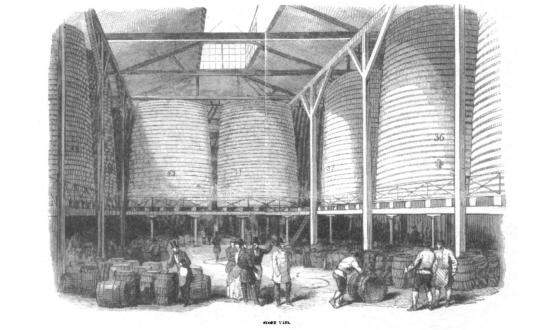

Those who preferred to drink beer rather than tea were even more exposed to harmful adulterations. Two official inquiries had recently been carried out into the liquor trade – one by a House of Lords Committee in 1850,9 the other by a Select Committee on Public Houses in 1853–4;10 both were bitter indictments of the Beerhouse Act of 1830, which had brought into existence no fewer than 123,000 beer-shops, virtually free from any control or supervision and notorious for the bad quality of the liquor they supplied. Before 1830 porter sold at 5d a quart. Now it was offered at 4d and even 3d a quart, but only by diluting and adulterating – there was an agreement among the London brewers to sell at 33s a barrel, and 3d a quart would only yield 36s. The brewers apparently had little interest in the quality at which their beer was ultimately sold in tied houses so long as a large ‘draught’ was kept up since this determined the selling-price of the property. According to George Ridley, an analyst, the most common adulteration by publicans was simple dilution, followed by the addition of sugar and salt to restore flavour and copperas or sulphate of iron to give a ‘cauliflower head’ by which ignorant customers judged strength. A favourite recipe of publicans recommended ‘To a barrel of porter, 12 gallons of liquor (water), 4 lb of foots (coarse sugar), 1 lb of salt, and then there is something to bring a head up, a little vitriol, cocculus indicus, also a variety of things so very minute that… we cannot easily detect the small proportions.’ In this way thirty-six gallons was turned into forty-eight, sold at 3d a pot, and yielded a profit of 15s a barrel.11 Nor was this kind of practice restricted to London. The Chief Constable of Wolverhampton reported that he had made a number of convictions for narcotics such as grains of paradise in beer, and believed that much apparent drunkenness was due to this and the use of similar drugs.12 The Report on Public Houses concluded by recommending the early initiation of a separate inquiry into the whole question of adulteration of food, drink, and medicines – a suggestion which resulted in the appointment of the Committee of 1855–6. Again, a mass of evidence was presented here about the malpractices of brewers, ‘brewers’ druggists’, and publicans. George Phillips, the Chief Officer of the Chemical Department of the Inland Revenue stated that of forty samples of hops recently analysed thirty-five contained grains of paradise, quassia, gentian, chiretta, and coriander; cocculus indicus has been added to one, and tobacco to another.13 Dilution with water, restoration of bitterness with quassia or gentian and of ’strength‘ with cocculus indicus, and the use of sulphate of iron for ’heading‘ were the stock-in-trade of most, if not all, publicans – in analysing two hundred samples of beer during the last nine years the chemist, John Mitchell, had not found one to be pure except some taken direct from the brewery.14

Similarly, Mitchell reported that every sample of bread he had examined, whether from poorer or wealthier districts, contained alum on an average of 40 grains to the 4-lb loaf; boiled potatoes and carbonate of ammonia were also used, and in flour he had found sulphate of lime and chalk used as whiteners and cheap additions to bulk. Bad as this was, Mitchell’s evidence did perhaps do something to reassure public fears about one suspected adulteration. Ever since Accum’s day there had been persistent rumours about the use by bakers of burnt or ground bones in bread; Mitchell testified that his analyses had never revealed their presence, and in fact no reliable witness either in 1855 or subsequently was able to prove their presence. In almost every other case, however, the worst fears of the Committee were realized and often exceeded. Chicory, ochre, roasted corn, and crusts of bread in coffee; butter, the greater part of which was merely curds; sulphuric acid, grains of paradise, cocculus indicus, and alum in gin; brick dust, tallow, peroxide of iron, ground shell, and ground biscuit in cocoa; green pickles, bottled fruits, and vegetables coloured with copper; anchovy sauce and potted meats coloured with bole armenian – these were only a few of the revelations which the Committee heard in an atmosphere of shocked incredulity which slowly turned to anger. By the end of the sitting it was certain that some form of general legislation against adulteration would be recommended, that a case for interference had been fully made out on grounds not only of public health but also of morality. The nation whose life depended on her trade was being made to look very like a nation of thieves.

Voluntary reform

For some years before legislation became effective in 1875 the quality of food and drink began to show noticeable improvement. Quite suddenly in 1855 adulteration had become news, and the widespread publicity given to the subject shaped and crystallized a public conscience which found expression in the press and the popular literature of the day as well as in Parliament and the columns of medical journals. The intervening years saw the spontaneous emergence of agencies of voluntary reform – societies instituted to campaign for legislative control, organizations avowedly established for the supply of unadulterated provisions, and a remarkable expansion of the co-operative retail of pure food. By the 1860s a climate of opinion had been formed which induced significant numbers of manufacturers and traders to put their own houses in order before they were compelled to do so; the measures of reform voluntarily undertaken by the trade therefore form an important prelude to the legislative suppression of adulteration.

In the creation of this public conscience the literature of adulteration played a fundamental part. Accum’s Death in the Pot had fired the public imagination in the 1820s, but his subsequent ‘disgrace’ had allowed the subject to be conveniently forgotten, and in the intervening years it received only passing mention in commercial15 and technical16 treatises. John Mitchell’s Falsification of Food, published in 1848, set a new standard by its original chemical analyses and detached style of expression, but its influence scarcely penetrated outside scientific circles. Widespread interest in adulteration had to be re-created in the 1850s, and the event which did this, and which precipitated a Parliamentary inquiry and, ultimately, legislation, was the Lancet series of articles between 1851 and 1854. Hassall had been immediately struck by the low quality of London food when he came to practise there in 1850, and within a few months had written a paper for the Botanical Society on the Adulteration of Coffee based on his own microscopical examination of random samples; shortly afterwards, Wakley wrote to him stating his opinion that mere exposure of the techniques of adulteration would achieve little unless accompanied by the names and addresses of the dealers who sold impure goods. This was the origin of the formidable, and hazardous ‘Analytical Sanitary Com-mission’ of the Lancet, which for four years conducted a weekly survey of every major article of food and drink and fearlessly published the names of hundreds of fraudulent traders. Hassall’s insistence on detailed personal examination, his refusal to accept preconceptions derived from earlier writers, above all, his original development of the microscope as an aid to detection, ensured that there could be no mistake. Hassall represented the dispassionate scientist pre-eminently acceptable to the Victorian intelligentsia, and his approach to a subject which had accumulated an assortment of truth, half-truth, and legend was exactly what the situation demanded.

Equally important, the somewhat indigestible material of Hassall’s articles was popularized in a number of ways which brought the substance of his discoveries to a far wider public. Several daily newspapers regularly reproduced the current Lancet article in abbreviated and simplified form, The Times especially being a consistent supporter. Of the journals the Illustrated London News, Fraze’s Magazine, Once a Week, the Quarterly Review, and the London Review devoted considerable space to able articles by Andrew Wynter and others – the latter’s Our Peck of Dirt for example being an amusing account of the consternation of a party of friends on discovering that the polony they had just ‘enjoyed’ for breakfast was composed of highly flavoured putrid meat, the coffee contained dried horse’s blood supplied by the knacker’s yard, and the cream was thickened with calves‘ brains!17 Also, the Lancet articles were the source of inspiration for a whole series of books and pamphlets whose object was to inform and warn in a simple way about current frauds and dangers to health; of these we may mention J.D. Burn’s The Language of the Walls, published in 1855, which devoted half its pages to adulteration, the anonymous Tricks of Trade in the Adulterations of Food and Physic and Dr Marcet’s On the Composition of Food, and How it is Adulterated of 1856, and in 1857 Dr John Postgate’s A Few Words on Adulteration. The same year also saw the publication of a shorter treatise by Hassall, aimed at the general reader, entitled Adulterations Detected in Food and Medicine, while other contemporary works such as Dodd’s Food of London and Edward Smith’s Foods and Practical Dietary also included substantial references to the quality of food. Many of these achieved a large circulation and ran into several editions, and there is no doubt that they diffused an awareness of adulteration among a wide public who would never have opened the pages of the Lancet, and, more particularly, produced a deep effect on the middle-class conscience.

One immediate effect of the publicity of the 1850s was in the awakening of interest among the medical profession. A list of those who began testing samples and canvassing for reform would include the names of Henry Letheby, Alphonse Normandy, John Simon, Robert Dundas Thomson, John Mitchell, and Sir John Gordon, to mention only a few, but the man who engaged himself most indefatigably and effectively in the campaign was John Postgate, a Birmingham surgeon and lecturer on anatomy at Sydenham College. His interest in the subject dated from 1853 when he had to treat a patient who was suffering from the effects of adulterated coffee, and this led him to examine the quality of Birmingham food generally, and bread in particular. He had been astonished to discover that, as in London, it was next to impossible to obtain a pure loaf – that nearly all contained alum and that potatoes, pea- and bean-meal were also frequently added. By 1854 he had become convinced that adulteration was one of the leading causes of disease in the great towns, and was in extensive correspondence with other doctors and chemists, was addressing public meetings, and forming local societies to campaign for suppression and control. It was, in fact, a letter which Postgate wrote to William Scholefield in January of that year suggesting a Committee of Inquiry which led to the appointment of the Select Committee of the House of Commons; by July 1855 the Committee was in session, and within another five years the first general Adulteration Act was on the statute-book.

Before this, however, a noticeable improvement in the quality of many foods had already taken place. When Hassall published his second volume in 1857 he was able to report that some manufacturers and traders had completely abandoned adulteration, many had at least given up the use of poisonous ingredients, and almost all had made some concessions to the growing public demand for purer food. The immediate effect of the Lancet disclosures was the emergence of a movement for voluntary reform, in which a considerable section of the trade joined in a determination to set their houses in order before legislation compelled them to do so. By the late 1850s ‘pure and unadulterated’ had become a stock advertising slogan of dealers anxious to cash in on the newly awakened fears of the public – all too frequently it was the same spirit of competition which had prompted adulteration in the first place which now made it more profitable to offer, usually at a somewhat higher price, a commodity which was ‘guaranteed pure’ and bore the certificate of a doctor or analyst. In other cases, however, traders who had previously been ignorant of the injury they were causing were now genuinely determined to redeem their names and reputations. In either case, the result to the consumer was much the same. Within a few years he was for the first time in a position to exercise a choice between pure and impure food; legislation was ultimately necessary principally because large numbers of people, for one reason or another, continued to choose wrongly.

One striking instance of voluntary reform was when Thomas Blackwell, of Crosse & Blackwell, announced to the Select Committee of 1855 that his firm had recently given up, at considerable cost to plant, the coppering of pickles and fruits and the colouring of sauces with bole armenian. ‘After the articles which appeared in the “Lancet” four or five years ago we abandoned it… . We have had iron vessels made, which are coated with glass, and likewise we had one silver vessel made, but we found silver would not do.’18 He understood that other ‘respectable’ manufacturers had followed suit, although the public did not at first like their pickles brown instead of green, and preferred their anchovy sauce to look bright red: Blackwell had taken pains to advertise the reasons for the change, and believed that most people now preferred the genuine articles.

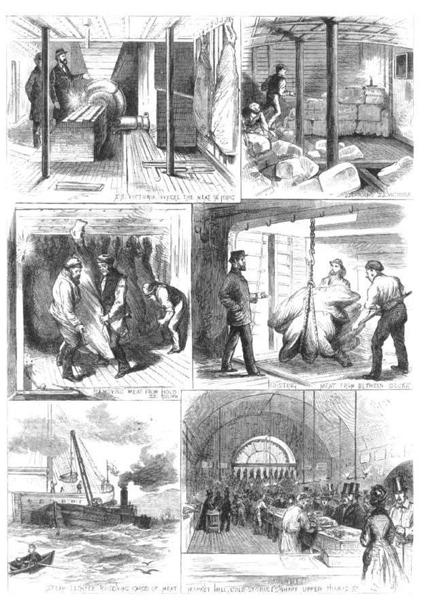

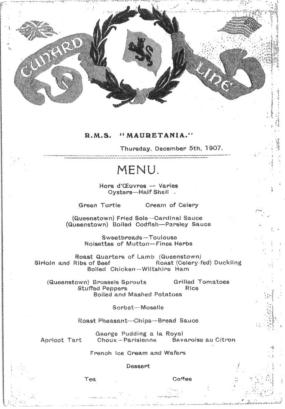

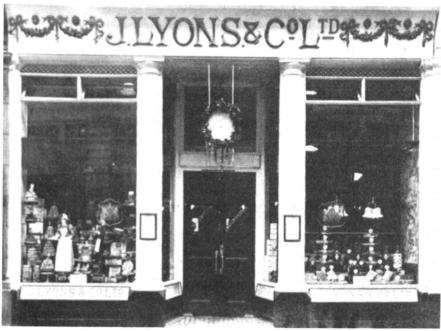

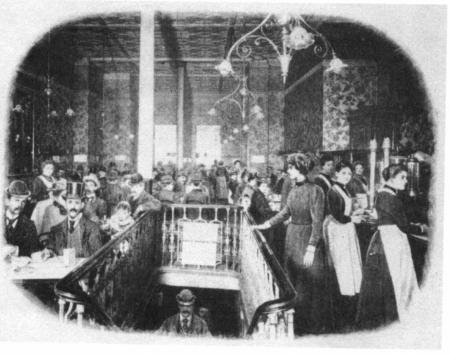

Another example of the direct influence of the Lancet articles was the establishment in 1851 of the Metropolitan Brewing Company ‘to supply the public with Genuine Beer’. It was launched with the considerable capital of £50,000, the prospectus stating that ‘the increasing support to this Company, which is formed expressly to supply a pure beverage, affords satisfactory proof that with increased means a large and profitable trade may be done.’ The baking trade was affected even more by the campaign for pure food, several large companies being formed to make bread free of alum and other adulterations; one, the Sanitary Commission Bread Company, was established in 1857 with Hassall as a director and a promise of a £50,000 investment from a single miller. Again, the grocery trade was similarly affected, several firms being set up for the supply of pure coffee and cocoa, uncoloured tea, genuine arrowroot, and so on. Horniman’s packet tea trade showed a remarkable expansion about this time, and by the 1870s was easily the largest in the country with an annual sale of more than five million packets. In addition to numerous retailers, at least one large wholesaler – the Universal Purveyor Company – was set up ‘for the supply of Articles of Domestic Consumption and Use Free from Adulteration and Fraud’. It undertook to provide groceries of all kinds, wines, spirits, and beer to a limited number of agents in London and the provinces: ‘Unexceptional references as to character, as well as ample security, will be required.’

Such reformist activities were no doubt also inspired partly by the changes in public taste which were occurring in the middle of the century. In the case of beer, for example, there was a marked swing away from the ‘hard, old beer’ of coaching days towards paler, brighter, less alcoholic drinks, so that many of the adulterations formerly practised to artificially age, strengthen, and darken it were no longer relevant. The same is true of tea, where there was a declining demand for green – the more heavily coloured variety – and a growing preference for black, especially when Indian teas became available in quantity. In other directions, too, a similar trend against highly coloured and strongly flavoured foods is recognizable, born, no doubt, partly of suspicion but partly, also, of a more sophisticated public palate.

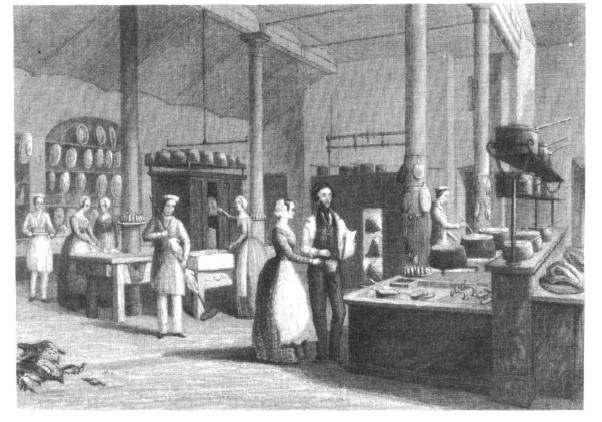

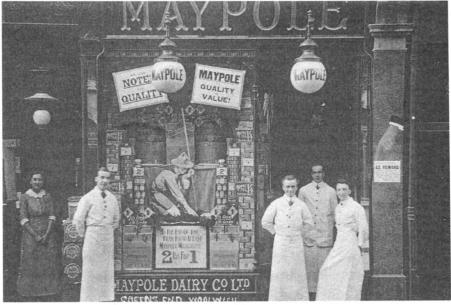

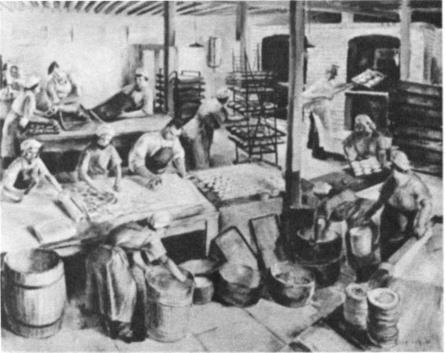

Finally, the important part played by the Co-operative Movement in making available to the working-class consumer food of a high standard of purity must not be undervalued. The measures of voluntary reform so far discussed affected almost exclusively the ‘respectable’ part of trade which catered for middle-class custom; for the poor, tied by debt to the local grocer and baker, there could be little improvement until the advent of effective legislation. In the intervening years, co-operation introduced a new ideal and a new practice into trade. Aiming as it did to restore economic and social purpose to buying and selling, the supply of pure goods was regarded as a principle as important as that of dividend on purchases – indeed, in numerous instances both before and after Rochdale it was pure food rather than cheap food which was the primary consideration. The earliest co-operative societies were isolated corn-mills and baking establishments formed towards the end of the eighteenth century in resentment against the frauds and extortions of millers and bakers – such was the Hull Corn-Mill Society established by local working men in 1795 to supply themselves with pure flour and bread, and numerous others came into existence after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The modern form of co-operative retail society dates, as we have seen,19 from the Rochdale Pioneers in 1844 and their numerous imitators; they too experienced great difficulty in obtaining supplies of pure food, which led them to revive the earlier idea of co-operative production. Already by 1850 the Rochdale society had its own mill, financed by the store, and others were in existence at Halifax, Leeds, and elsewhere.

The co-operative movement also illustrates the consumer-resistance which pioneers of pure food often had to meet and overcome. Holyoake himself had foreseen this difficulty, and had warned his audience at Rochdale in 1843: ‘When you have a little store and have reached the point of getting pure provisions, you may find your purchasers will not like them, nor know them when they taste them. Their taste will require to be educated. They have never eaten the pure food of gentlemen.’20 His words were prophetically true. The pure flour supplied by the Rochdale Flour Mill was darker in colour than members were accustomed to, and would not sell because of its brownness. The position was so critical for the society that for a time public pressure compelled it to produce white flour, but this involved such an abandonment of principle that a special Store Meeting shortly afterwards voted to return to purity, whatever the cost. Public confidence was gradually won and ultimately the unadulterated flour came to be greatly preferred. Another case in point was tea. The Co-operative Central Agency which was formed in 1850 to supply local societies with pure provisions, found that its green tea was unsaleable; the public, especially in the north of England, insisted that green tea should look bright and highly glazed, and at first rejected the dull, olive-coloured leaves which the Agency provided. Here too the good ultimately drove out the bad. Joseph Woodin, the Agency’s manager, published a pamphlet on adulteration in 1852 ‘in order to undeceive consumers in the manufacturing districts’, and lecturers were engaged ‘to go round the country and explain the matter to the working-classes’.21 The energetic and enterprising pursuit of such policies, often in the face of a hostile public, is a striking testimony to the faith of the early co-operators. Through them, and through them alone, some at least of the working classes were familiarized with a standard of purity they had never known, and were educated to an appreciation of the moral as well as the economic value of honest dealing.

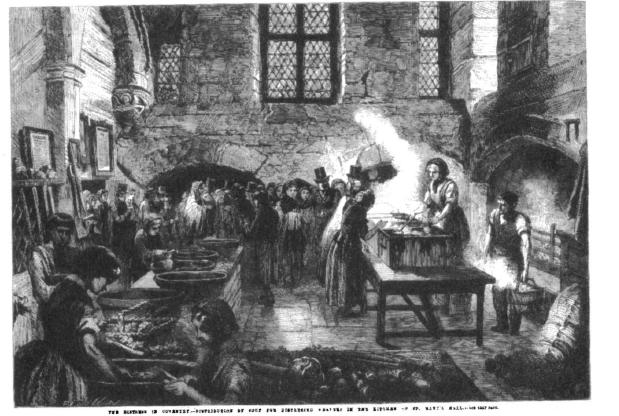

The early food legislation

Although voluntary reform did something to raise the quality of food in higher-priced shops and co-operative stores, the diet of the majority of the population continued to be heavily adulterated until effective pure food laws could be passed through Parliament. Publicity changed the character of the problem, but did not solve it: it is noticeable, for example, that after 1850 several of the cruder (and more easily detectable) frauds were gradually abandoned in favour of newer and more subtle methods which had a run of success until they too were exposed. When Hassall extended his survey for the Lancet to provincial towns in 1857–8 he found that adulteration in Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, and Liverpool was still rife, but not the almost universal practice it had been in the London of 1851. At the same time John Postgate published a collection of recent cases to show that fraudulent and even dangerous adulterations were still being carried on – his list included confectionery composed of twenty parts of sugar and ten of terra alba, which had caused the death of a child in Birmingham, and bread discovered in Hull which contained 5 per cent of silex or flint.22 The inferior ‘Cones’ flour, which was itself often adulterated with rye, barley, Indian corn, and bean-flour, was extensively used by ‘underselling’ bakers throughout the 1850s and 1860s,23 and, more serious still, Professor Odling discovered strong evidence of the deliberate addition of highly poisonous copper sulphate as a bread whitener.24 It had been used in Belgium and France in minute quantities since about 1830 for the same purpose as alum, although its effect was far more drastic; it had often been suspected here, but never before proved. If this were not enough, in 1860 Dr Edward Lankester showed that poisonous colouring matters in food were still very common, and quoted recent cases in which three people had died after a public banquet at which they had eaten green blancmange containing arsenite of copper, and of yellow Bath buns which owed their colour to sulphide of arsenic. The next year, a lecture delivered to the Royal Society of Arts claimed that 87 per cent of the bread and 74 per cent of the milk sold in London were still adulterated.

Voluntary forces alone would not have provided a sufficient check to adulteration of this extent, and from the publication of the House of Commons Committee’s final report in 1856 it was certain that legislation must shortly follow. But although Parliament and the nation had at last been convinced of the existence of a great and growing evil, wide differences of opinion existed as to the remedy to be adopted. There were many still like Viscount Goderich who looked in the first place to voluntary reform by traders and an extension of co-operative retail of food,25 while at the other extreme Hassall was demanding the creation of a central board of public analysts, with imprisonment and public exposure as the penalty for adulterators. Others again favoured the practice of France, where local Conseils de Salubrité harnessed the expert knowledge of doctors, chemists, and veterinary surgeons to guard the purity of all foods, drinks, and drugs.26

The first Adulteration of Foods Act which was passed in I86027 was therefore a compromise, steering an uncertain course between conflicting views. In common with much Victorian social legislation it suffered from all the failings of permissive adoption – the arguments of economy, the consideration due to vested interests, the sheer lethargy and inertia of much unreformed county administration. Under the terms of the Act various local authorities (the Commissioners of Sewers in the City of London, Vestries and District Boards in the Metropolis generally, and the Courts of Quarter Sessions in the counties) were empowered to appoint public analysts who would examine samples of food and drink (but not drugs) ‘on complaint made’ by private citizens. No provision was made for sampling; all the analyst could do was to wait for suspected articles to be brought forward by those public-spirited enough to pay a fee of up to 10s 6d for each analysis. No central authority was created. The responsibility for ensuring food quality was to be a local and purely optional one. A fine was to be the normal penalty for adulteration, with imprisonment only in default of payment, and a seller who could show evidence that he had himself been deceived, and was unaware of the adulteration, was not to be held liable.

To the bitter disappointment of radical reformers like Hassall and Postgate, the first Food Act passed onto the statute-book and into oblivion. All the evidence suggests that it was an utter failure. Trade opposition prevented the adoption of the Act over wide areas, and during the twelve years of its existence only seven analysts were appointed throughout Great Britain. Four of these did nothing at all. Two more had a few samples submitted to them during the first year or so, mainly by dealers who knew that their goods were pure and wanted an analyst’s certificate for publicity purposes, but none subsequently. One of these, Dr Henry Letheby, the Public Analyst for the City of London, was called on to examine fifty-seven samples in the course of nine years; although twenty-six were reported as adulterated, in no case were proceedings brought before the magistrates in accordance with the provisions of the Act.28 Only Dr Charles Cameron, the Medical Officer of Health and Public Analyst for Dublin, demonstrated how energy and initiative could transform a lame measure into effective operation. Between 1862 and 1874 he analysed 2,600 samples, reported nearly 1,500 as adulterated, and successfully obtained convictions in 342 cases.29

It should, however, be remembered that in 1860 legislative interference with the free workings of the economy was still exceptional and limited in scope. The mere attempt to place a law between seller and buyer was a major breach in the structure of laissez-faire and a significant contribution to the scanty public health provision of the day, and although the Act itself was ineffectual the important precedent had been established that it was within the proper role of the state to protect the consumer against injury to his pocket and his health. Throughout the 1860s a stream of criticisms and demands for more effective safeguards was kept up by the reformers. The Lancet continued to provide the spearhead of the attack, supported by the Royal Society of Arts, the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, and individuals among whom Postgate and Letheby stand out, while Hassall himself demonstrated by a new series of investigations that, although some improvement had taken place since his first inquiry, an urgent problem still awaited solution in London and the leading provincial towns. On this occasion, half the samples of bread analysed contained alum in amounts ranging from 12 to 96 grains to the 4–lb loaf.30 In 1868 John Postgate laid before Parliament a series of radical amendments to the 1860 Act which, after numerous delays and modifications, passed into law as the Adulteration of Food, Drink, and Drugs Act, 1872.

The most important legal changes in the new Act were that it now became an offence to sell a mixture containing ingredients for the purpose of adding weight or bulk (for example, chicory in coffee) unless its composition was declared to the purchaser, and that the sale of adulterated drugs now became punishable. Administratively, the Act extended the power of appointing analysts to boroughs having separate police establishments: the appointment was still to be optional ‘save on the direction of the Local Government Board’, an important, if ill-defined amendment which introduced an element of central control. Another valuable clause provided for the procuring of samples for analysis by Inspectors of Nuisances and other local officers, as well as by private persons. In all these respects the new Act was a great advance on its predecessor, more extensive in scope, and more vigorous in its enforcement. Within three years 150 out of the 225 districts empowered to appoint analysts had done so, and over 1,500 convictions for adulteration had been obtained. One of these newly appointed public analysts, Wentworth Lascelles Scott, has left a picture of the kind of work and the extent of adulteration at this period.31 During fifteen months in north Staffordshire he took 937 random samples of food, drink, and drugs, of which 381 were adulterated and reported. The greatest problem was milk, more than half the samples of which were diluted with highly impure water, but twenty-six out of eighty-nine samples of beer were adulterated, six of them with the deadly cocculus indicus. More than half the samples of mustard were impure, containing flour and turmeric, while more than a third of the samples of pepper contained sand and a variety of vegetable matters. On the other hand, some foods already showed a marked improvement in quality: only two samples of bread were reported against, and only one out of twenty-two pieces of sugar confectionery now contained chromate of lead.

In other ways, however, the working of the new Act was still unsatisfactory. Its adoption was very uneven, and there was nothing to ensure that an analyst, once appointed, would have anything to do – the analyst for Somerset, for example, obtained 520 convictions in sixteen months while his colleague in Shropshire obtained two in twice as long. Many analysts were inexperienced, and even among the experts there were wide differences of opinion as to what constituted adulteration: a fundamental difficulty was that no agreed standards had yet been set, so that divergent opinions were held about the minimum percentage of ‘fats’ and ‘total solids’ in milk, whether the ‘facing’ of tea should be regarded as an adulteration, and so on. Analyst contradicted analyst, and confused magistrates gave conflicting decisions. After numerous petitions had been received from the larger towns complaining of these weaknesses, the Government appointed in 1874 a new Select Committee whose Report embodied most of the criticisms already mentioned.32 The 1872 Act, the Report claimed, had been productive of much good in that ‘people were now cheated rather than poisoned’, but it was in need of amendment chiefly ‘in order to give a clearer understanding as to what does and as to what does not constitute adulteration’. The result of this Report was the Sale of Food and Drugs Act, 1875, which, with numerous amendments, forms the basis of the present law.

The establishment of food purity

Within a decade of the passing of the new Act a remarkable improvement had been effected in the quality of basic foods – so much so that a good case may be made out for regarding the 1880s as the crucial period in the suppression of adulteration and the establishment of food purity. The most formidable penalty in the new Act lay in Section 3, which made any adulteration injurious to health punishable with a heavy fine and with imprisonment for a second offence, a remedy which food reformers had been urging ever since the time of Accum. In fact, however, for a seller to be liable under this section it was necessary to prove guilty knowledge on his part, and only in exceptional circumstances was such evidence forthcoming. The effective part of the Act lay in Section 6, which provided that no one should sell, to the prejudice of the purchaser, any article of food or any drug which was not ‘of the nature, substance and quality of the article demanded’: here it was not necessary to prove that the adulteration was injurious to health, or that the seller had knowledge of it.33 There were, of course, difficulties of interpretation even here. If, for example, a seller notified the public that his goods were adulterated, could consumers still claim that they were ‘prejudiced’ in the meaning of the section? In the case of Sandys v. Small in 1878 whisky had been sold by a publican thirty degrees under proof, but conspicuous notices had been posted in the bar stating that ‘All spirits sold here are mixed’. Nothing was said at the time of sale, and the customer had not in fact seen the notice. The Queen’s Bench Division held that as the purchaser was ‘informed’ constructively beforehand of the mixture it was not to his prejudice and the publican had therefore committed no offence. Although difficulties arose in practice as to what constituted ‘constructive notice’, there was little quarrel with the principle of the ruling. The decision in James v. Jones (1 Q.B., 304, 1894) however, seems far less defensible, and represented a serious limitation on the working of the Act. In this case it was decided that baking-powder was not ‘an article of food’ within the meaning of the Act, apparently on the ground that it was never eaten alone although, of course, the sole purpose of its manufacture was for use in food. The seller of baking-powder containing 40 per cent of alum, which the judge himself admitted was ‘injurious to health’, was therefore not liable. The somewhat illogical conclusion followed that the sale of injurious baking-powder was not actionable, but the sale of bread which contained it was.

With this exception, adequate legal machinery for the suppression of adulteration now existed. Effective enforcement of the Act, however, depended upon two main factors – the readiness of local authorities to adopt what was still permissive legislation, and the skill and efficiency of the public analysts themselves. The Local Government Board achieved much by persuading and cajoling authorities to appoint analysts, although in its annual report for 1880 it had to admit that in several large towns including Derby, Durham, Hartlepool, Northampton, and Oxford no action had been taken, and ‘we have too often been unable to obtain more than a general statement that as adulteration is not suspected to exist, the Town Council deems it unnecessary to harass the local tradesmen.’34 During the decade, however, the tone of the Board’s circular letters gradually became more authoritative, and within a few years nearly all authorities had fallen into line and had instituted regular sampling; by 1889 the Board’s target of one sample per thousand of the population had been reached with a total of 26,954 analyses for the year. The public analysts themselves appear, on the whole, to have been a skilled and dedicated group of men, keenly anxious to make the Act work and to increase its efficiency. The Society of Public Analysts was founded in 1874, like many professional bodies, out of informal meetings of colleagues; within a few months it had enrolled almost every practitioner in the country, had laid down a definition of adulteration, was holding regular meetings and publishing its proceedings. There is no doubt that the activities of the Society gave a considerable stimulus to analytical chemistry in general and to the development of new tests and standards for food purity in particular,35 and the Society played an especially important part in establishing limits outside which they would regard an article as adulterated, many of which were eventually adopted legislatively. The first statutory standards for spirits were laid down in 1879, for the new product ‘margarine’ in 1887, for milk in 1901, and for butter in 1902, and by 1914 a wide range of foods had become subject to legal minima.

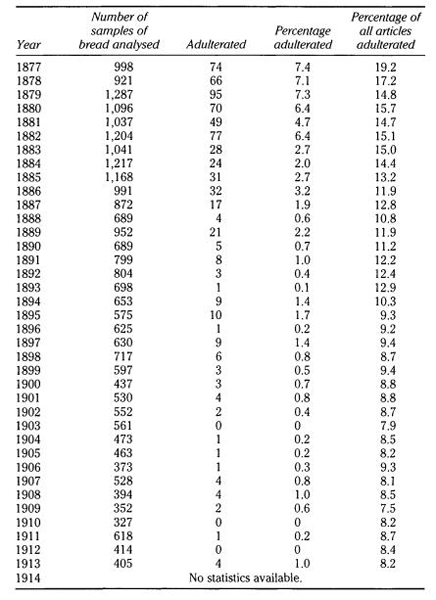

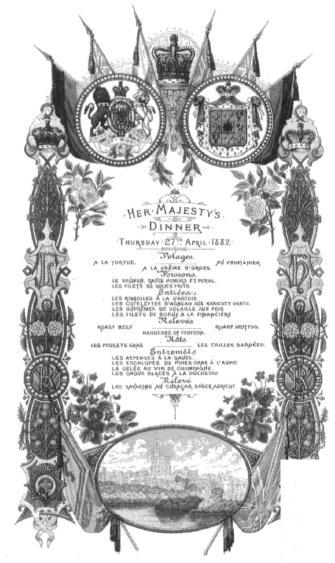

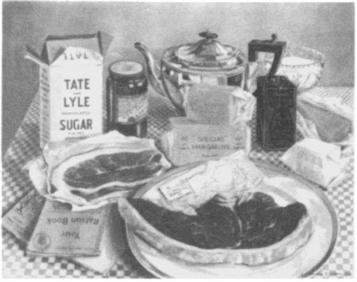

One of the most valuable terms of the 1875 Act provided that public analysts were required to make quarterly statistical returns to the Local Government Board, and from these it is possible to compile an exact record of the gradual conquest and suppression of adulteration from this time onwards. As Table 25 shows, when returns were first published in 1877, 19.2 per cent of all the random samples analysed throughout the country were adulterated; by 1900 the figure had fallen to 8.8 per cent, and in 1913 it stood at 8.2 per cent. A spectacular improvement in the quality of many basic foods occurred during the 1880s, so that by the end of Victoria’s reign the consumer generally received his bread and flour, his tea and sugar, as pure as he could wish. Some items, it is true, still presented an intractable problem which showed little improvement over the years – 13 per cent of all beer was still adulterated in 1900, 12.4 per cent of spirits, 10 per cent of coffee, and 9.9 per cent of milk, despite constant watch and repeated prosecutions by local authorities. But the chief offence in most of these cases was simple dilution with water, which remained easy, profitable, and difficult to detect. Deliberate, dangerous adulteration for the sake of gain had been all but eliminated.

Of the improvement of basic foods, that of bread was most marked. In the early years of the new Act, public analysts naturally concentrated much of their attention on it, and the paper read at the very first meeting of the Society was given by Professor Wanklyn ‘On the detection of alum in bread’. The Lancet survey of 1872 had found that half of all the samples examined were still adulterated: in the first year of returns the figure had fallen to 7 per cent and by 1884 to as little as 2 per cent. This good result was partly due to an energetic drive by the authorities in tracking down and prosecuting offenders, partly to the improved quality of imported wheat and the introduction of roller-milling, which made the use of alum as a whitener unnecessary except to the lowest class of baker. Isolated cases of gross adulteration could, of course, still be found. In 1880, for example, the Public Analyst for Essex reported on one 4–lb loaf which contained

the unprecedented quantity of 1,035 grains of alum, and would have been ‘exceedingly harmful to anyone whom its nauseousness did not prevent from consuming it’.36 Possibly this huge amount had gained access to the bread indirectly as a result of the use of alum in baking-powder where it was employed as a cheap substitute for tartaric acid,37 and this continued to be a common practice until the Sale of Food and Drugs Act of 1899 widened the definition of food to include ‘any article which ordinarily enters into or is used in the composition or preparation of human food’. Oatcakes containing 10 per cent of chalk were reported in 1880, and muffins which included plaster of Paris two years later,38 but cases of this kind were now isolated survivals from an earlier epoch. The Local Government Board Report for 1892 could say with some satisfaction, ‘It is now certain that the bread supplied to the people of England is practically pure.’

The quality of tea showed an even more dramatic improvement than that of bread under the influence of the 1875 Act. An investigation of 1872 had found thirty-six out of forty-one samples grossly adulterated with such things as sand, magnetic iron, China clay, Prussian blue, and spurious leaves,39 but within a decade tea adulteration had all but disappeared, and from 1886 onwards it became a rarity to find even a single case reported in a year. Under the 1875 Act tea was subjected to a double scrutiny – once on arrival in the country by the Customs Department, and again by the public analysts if domestic adulteration was suspected – and it would be surprising if more than a fraction of impure tea had continued to slip through. Added to this, the declining popularity of green China teas, always the more highly adulterated, and the preponderance of Indian and Ceylon teas, whose purity had never been in question, finally put an end to what had been one of the most serious of all adulterations. By the 1880s grocers were finding it difficult to sell China teas unless they could guarantee them ‘pure’ or ‘free from colouring matters’, and even then, much was only sold at a loss, and not re-stocked.40 By the end of the century, it seems, Chinese merchants had in fact stopped the colouring and ‘facing’ of tea, and only an occasional Caper was reported against for containing an excess of mineral matter. With the fall in price of imports and the vigilance of public analysts, the English grocer also abandoned his former malpractices in the 1870s: the worst that can be said of him in the later nineteenth century is that he occasionally mixed cheap, inferior China teas with strong Indian varieties to lower cost or increase his profit. In any case, an Indian tea which contained 10 per cent of China ‘rubbish’ and sold at under 2s a pound was a far better buy than the heavily adulterated China tea for which mid-Victorian customers had paid three or four times as much.

Beer adulteration had also practically ceased to exist by 1880, except for innocuous dilution. Fables continued to circulate, particularly at temperance meetings, about the poisonous ingredients allegedly used by brewers—a speaker in 1883 made the unsupported statement that 245,000 cwt of ‘chemicals’ were annually used in English breweries,41 and a few years later a book purporting to be a serious study of drinks and drinking habits stated that bitterness in beer was produced by strychnine, absinthe, and nux vomica, and intoxication by belladonna, opium, henbane, and picric acid.42 In fact, cocculus indicus was last reported in 1864 and grains of paradise in 1878, and only rarely after this were old adulterations such as ‘heading’, capsicum, and liquorice discovered by public analysts as isolated curiosities. Narcotics disappeared from beer with the vigilance of local authorities and a change in drinking habits: by the closing decades of the century people no longer wanted to be stupefied and had turned away from porter and ‘hard beer’ towards lighter, less alcoholic varieties. Dilution remained the outstanding problem, and a seemingly intractable one: as late as 1900 one in five samples was watered, and a great many of these salted in order to restore lost flavour and, no doubt, increase thirst.

In the summer of that year, however, something far more serious occurred. A mysterious disease, variously described as ‘alcoholism’ and ‘peripheral neuritis’, appeared in Manchester and Salford and spread into the midlands as far south as Lichfield and Nottingham; by the end of the year 6,000 cases had been reported, and seventy people had died. Those affected were generally heavy drinkers, and it was not long before a Manchester doctor traced the illness to arsenical poisoning in beer.43 Ultimately the source was traced to a firm of brewing sugar manufacturers, Bostock & Co., of Garston, who manufactured their glucose by a process involving commercial sulphuric acid. It was this sulphuric acid, itself made from arsenical iron pyrites and supplied by a Leeds firm, which was responsible for the outbreak. One, if not both, manufacturers had been morally guilty of criminal negligence in using, without testing, a substance in the production of human food which is liable to contain poisonous impurities. A Royal Commission on Arsenical Poisoning (1901–3) subsequently recommended that a legal maximum of not more than one-hundredth of a grain of arsenic per gallon of liquid or per pound of solid food be enforced (up to four grains per pound of brewing sugar had been found) but this was bolting the stable door after the horse had departed. The arsenic scare of 1900 added considerable force to the arguments of those food reformers who at the end of the century were urging that a new problem had now emerged and was awaiting solution – that of ‘legalized adulteration’.44

The bread debate

By the close of the century public anxiety was turning from traditional forms of adulteration, now apparently under effective control, towards wider issues of food quality and nutrition. The new science of dietetics, headed by such men as Drs Paton and Hutchinson, pointed to inadequate diet as a main cause of ‘incapacitated manhood’ which alarmed the nation at the time of the Boer War, though opinions differed as to whether the poor state of the nation’s health was due to a deterioration in the quality of diet, to ignorance and laziness on the part of housewives, or quite simply, to poverty. Attention naturally focused on bread, still the staple food of the working classes. Although alum and other adulterants were virtually things of the past, almost all bread was now made from white, roller-milled flour of low extraction rate from which the bran and wheat-germ had been removed. Opposing this, a ‘brown bread’ lobby, initially composed mainly of middle-class vegetarians, socialists, and ascetics, dated from the 1880s, when May Yates founded the Bread and Food Reform League and Dr T.R. Allinson began campaigning on behalf of wholemeal bread. Their main obstacles were that the brown bread then available was more expensive than white, and tended to be unpalatable, with a thick crust and a moist, sodden interior.45 However, further support was given to the League’s cause in 1911 by F.G. Hopkins: although vitamins had not yet been discovered, he argued that the superior value of bran flour was due to ‘unrecognized food substances, perhaps in very minute quantities, whose presence allows our systems to make full use of the tissue-building elements of the grain’.46

The same year, the Local Government Board commissioned Dr Hamill to investigate the bleaching and ‘improving’ of flour by millers. Bleaching by nitrogen peroxide gas had spread rapidly since the patenting of the process in 1901, as had the use of various chemical additives which were supposed to improve baking qualities. Hamill concluded that it was not desirable that ‘such an indispensable foodstuff as flour, the purity and wholesomeness of which are of first importance to the community, should be manipulated and treated with foreign substances, the utility of which from the point of view of the consumer is more than questionable’.47 No new legislation against such additives was forthcoming and, surprisingly, a test case brought in 1913 by Hull Corporation against a local firm of millers for adding potassium persulphate as an ‘improver’ was held by a magistrates’ court not to be an adulteration under Section 6 of the Sale of Food and Drugs Act, 1875: apparently the case was not taken to appeal.

These anxieties about the composition of bread affected only a small minority of consumers, who tended to be regarded as cranks and faddists. Most people preferred the very white flour produced by the roller-mills, and by 1900 the white, wheaten loaf comprised at least 95 per cent of total bread consumption by weight.48 From the 1880s, however, a small, specialist market for certain ‘patent’ breads claiming nutritional advantages began to grow, mainly among diet-conscious, middle-class consumers: they included Hovis (reinforced wheat-germ), Daren (wheat, wheat-germ, and rye), Triagon (wheat, maize, and rice), and Kermode’s (wheat and maize). Only Hovis had achieved a national reputation by 1914, mainly as a result of successful advertising. The flour formula had been invented in about 1885 by Richard Smith, a miller of Stone, Staffordshire: the product was renamed ‘Hovis’ (from the Latin for ‘strength of man’) in 1891 and the Hovis Bread Company established in 1898. In fact, the company merely manufactured the flour, but did not bake bread: the strategy was to win over bakers – and, ultimately, consumers – by national advertising through brand-name packaging, sign-boards for delivery vans and cafes, and baking tins with the Hovis imprint. Country teashops displaying ‘teas with Hovis’, and serving it in specially designed Hovis tea-sets, became well-known to Edwardian cyclists and early motorists. It was the first successful attempt to exploit the new health food market on a national scale, and evidence of a growing dietary awareness among a small, though influential, section of the population.

Notes

1 Hassall, Arthur Hill (1855) Food and its Adulterations; comprising the Reports of the Analytical Sanitary Commission of ‘The Lancet’ for the years 1851 to 1854 inclusive.

2 ibid., 279.

3 ibid., 600 et seq.

4 Reports from the Select Committee on Adulteration of Food, etc., Third Report, HC 379 (1856), VIII, 1.

5 Warington, R. (1851)‘Observations on the teas of commerce’, The Memoirs of the Chemical Society (May); Adulteration of Food, report cit., First Report, HC 432 (1855), VIII, 221: Appendix, 135.

6 Central Co-operative Agency. Instituted under Trust to counteract the system of adulteration and fraud now prevailing in the trade. Catalogue of Teas, Coffees, Colonial and Italian Produce, and Wines etc., with the Retail Prices affixed, sold by the Central Co-operative Agency at the Central Establishment, 76 Charlotte St, with Prefatory Remarks on Adulteration, arising from competition. J. Woodin. 1852, 28–9.

7 Adulteration of Food, op. cit., Third Report (1856): Evidence of J. Woodin, 270–3.

8 The Times, 27 May 1851.

9 Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords appointed to consider the Operation of the Acts for the Sale of Beer, etc. (1850), (398) XVIII.

10 Report from the Select Committee on Public Houses, etc., together with the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index (1853–4), HC (367) XIV, 231.

11 ibid.: Evidence of George Ridley, Qs. 4681–4868.

12 ibid.: Evidence of Gilbert Hogg, Qs. 6523–6975. So also did the Rev. H. Fearon, B.D.: ‘But is it really beer which our work people nowadays get to drink? … Look at that poor degraded man, reeling in his gait and now sinking helplessly down unconscious upon a doorstep in the street. You say he is intoxicated … I believe he is drugged…. Do not lay solely to the charge of malt and hops what is due to cocculus indicus, tinctured with tobacco and spiced with grains of paradise’ – Home Comfort: Working Life, how to make it happier. A lecture given before the Young Men’s Institution at Leicester (1857), 11–13.

13 Adulteration of Food, report cit., Second Report, HC 480 (1855), VIII, 373: Evidence of George Phillips, Q. 2304 et seq.

14 ibid., First Report: Evidence of John Mitchell, Q. 1073 et seq.

15 e.g. McCulloch, J.R. A Dictionary, Practical, Theoretical and Historical, of Commerce and Commercial Navigation (edns of 1834 and 1846); P.L. Simmonds (1846) Commercial Products.

16 e.g. Ure, Andrew (1835) A Dictionary of Chemistry and Mineralogy (4th edn); Jonathan Pereira (1843) A Treatise on Food and Diet.

17 Wynter, Andrew (1869) Our Social Bees. Pictures of Town and Country Life, and other Papers (10th edn), 76 et seq.

18 Adulteration of Food, op. cit., First Report (1855): Evidence of Thomas Blackwell, Qs. 1567 and 1602.

20 Holyoake, G.J. (1908), The History of Co-operation, 272.

21 Adulteration of Food, op. cit., Third Report (1856): Evidence of J. Woodin, 270–3.

22 Postgate, John (1857) A Few Words on Adulteration, 3 et seq.

23 Report relative to the Grievances of the Journeymen Bakers, etc., op. cit., 1862, XLI.

24 ‘On the composition of bread’ by William Odling, Professor of Practical Chemistry at Guy’s Hospital, in the Lancet I (1857), 137–8.

25 Goderich, Viscount, MP (1852) ‘On the adulteration of food and its remedies’, in Meliora, or Better Times to Come, Viscount Ingestre (ed.) (2nd edn).

26 The first Conseil de Salubrité was established in Paris as early as 1802, and most French provincial towns followed the example during the next two or three decades.

27 For a fuller examination of the Act and its historical setting, see John Burnett (1960) ‘The Adulteration of Foods Act, 1860: a centenary appreciation of the first British legislation’, Food Manufacture XXXV (November), 479 et seq.

28 Letheby, Henry (1868) On Food: being the substance of four Cantor Lectures delivered before the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, Jan. and Feb. 1868, 71.

29 Scott, Wentworth Lascelles (1875) ‘Food adulteration and the legislative enactments relating thereto’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts XXIII, 433.

30 Lancet I(1872), 26.

31 op. cit., 433 et seq.

32 Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Adulteration of Food Act (1872), HC 262 (1874), VI, 243.

33 Legal ingenuity practically nullified the working of this section in the first few years by the interpretation given to ‘prejudice’. In a number of decisions immediately after 1875 it was held that if a sample was purchased by an inspector for analysis he was not ‘prejudiced’ by an adulteration since he had not bought the food for his own consumption. As practically all samples were taken in this way, and not by private purchasers, the provision became for a few years almost a dead letter. This unfortunate line of decisions and the narrow interpretation of ‘prejudice’ was brought to an end in the appeal case of Hoyle v. Hitchman in 1879.

34 Tenth Annual Report of the Local Government Board, 1880–81 (1881), 1XXXVI.

35 Dyer, Bernard and Mitchell, C. Ainsworth (1932) The Society of Public Analysts: some reminiscences of its first fifty years, and a review of its activities.

36 Local Government Board, op. cit., xc.

37 Robinson, H. M. and Cribbs, C. H. (1895) The Law and Chemistry of Food and Drugs, 337–46.

38 The Analyst 7 (1882), 115.

39 Liverseege, J.F. (1932) Adulteration and Analysis of Food and Drugs. Birmingham methods and analyses of samples. Review of British prosecutions during half a century, 318.

40 Anon (nd, c. 1884) The Art of Tea Blending. A Handbook for the Tea Trade, 37.

41 Quoted in John Bickerdyke (1886) The Curiosities of Ale and Beer.

42 Mew, J. and Ashton, J. (1892) Drinks of the World.

43 British Medical Journal, 24 November 1900.

44 See e.g. article by W. C. Quilter in 1887 in Nineteenth Century; and A. Gordon Saloman (1887) ‘The purity of beer’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 35, 246 et seq.

45 Hunt, Sandra The Changing Place of Bread in the British Diet in the Twentieth Century, series of upublished research papers sponsored by the Rank Prize Funds (Brunei University), ‘The structure and economics of the baking and milling trades, 1880–1914’, 17.

46 ibid., 19.

47 Hamill, J.M. (1911) On the Bleaching of Flour, Local Government Board, Food Reports no. 12 (Cd. 5613).

48 Collins, E.J.T. (1976) The “consumer revolution” and the growth of factory foods. Changing patterns of bread-and cereal-eating in Britain in the twentieth century‘, in Derek J. Oddy and Derek S. Miller (eds), The Making of the Modern British Diet, 28.