3

3

The town worker

[Before the Industrial Revolution] the workers enjoyed a comfortable and peaceful existence… . Their standard of life was much better than that of the factory worker today.

F. Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845)1

The most revolutionary social change which took place during the first half of the nineteenth century — a change creating problems which have not yet been solved — was the rapid growth of towns, and particularly of the industrial towns of the midlands and north of England.

The cause of this change was, of course, the development of manufacturing industry associated with the Industrial Revolution which had begun in the latter part of the preceding century. Its origins were certainly earlier than 1750, and it can be argued that its completion is not yet, but there can be no doubt that the pace of change was very rapid, and very evident, between about 1780 and 1850 when, as a result of the invention of machines for spinning and weaving, and the development of the steam engine, the textile trades were transformed into factory industries centred in Lancashire and Yorkshire. Coal-mining and the iron industry were also growing rapidly in response to the new demands, while improved communications by canals, railways, and steamships were distributing the ever-increasing products of industrialism at home and overseas. Our period fitly ends with the Great Exhibition of 1851, which demonstrated in a spectacular way the industrial predominance of ‘the workshop of the world’.

But although industry was making such rapid strides, it is wrong to suppose that even at the end of this period England had become a mainly industrial society. Of 6,700,000 occupied persons classified in the census of 1841, only 2,619,000 derived their livings from commerce, trade, and manufacture: there were still a million and a quarter in agriculture, and very nearly a million in domestic service. Manufacture was moving up into first place, but industrialization was still far from being a completed process. Textiles was the largest industry in 1841 with 619,000 employees (just over half in factory employment, the rest in domestic spinning and weaving); the metal trades involved 303,000 and mining 173,000.2

Was this growing population of industrial workers better or worse off than their rural predecessors? Was the standard of life of the town worker higher than that of the agricultural labourer? Ever since the Industrial Revolution itself controversy has raged as to whether industrialization came as a boon or a curse to the English working classes, and an answer to the question seems little nearer today than it was a century ago. For one thing, complete and reliable statistics by which the standard may be measured — wages, prices, consumption of goods, and so on — are not available for the period under discussion. For another, the ‘standard-of-living controversy’ has been a favourite arena for opposing political beliefs. Most of the early writers of English economic and social history were socialists, imbued with the express or implied purpose of showing the development of capitalist industry as a calamity for the working classes: excessive and unhygienic factory labour, the exploitation of women and children, overcrowding in insanitary slums — these and many other evils have all been laid at the door of the factory system.3 Only in more recent years has the pessimistic account of emergent industrialism been repainted by a school of historians who see the factory system as the saviour of the masses, who point to the higher earnings of town workers compared to agricultural labourers, the advantages of separating work from the home, and the beneficial effects of factory employment on labour organization and on the status of women.4

Some of the recent writers have recognized that changes in diet may be a valid indicator of changes in the standard of living and have attempted to trace from the available statistics the course of per capita consumption in a number of basic foods. The consumption statistics for a number of foods have previously been cited (pp. 15–17); useful as they are in indicating national trends, however, they tell us little about the actual diets of groups and individuals who rarely, if ever, conform to the average. In reality there were very wide differences between the earnings — and hence, consumption habits — of skilled and unskilled workers, of factory operatives and unmechanized, domestic workers. To discuss ‘average’ consumption is to ignore the important economic results which industrialization did produce — improvement for some categories of labour and deterioration for others. Moreover, it neglects the fact that the first half of the nineteenth century saw the rise to importance of a virtually new social class whose consumption habits, in food at least, approached those of the landed gentry. Though still numerically small, the middle class of 1850, with its large families and armies of domestic servants, accounted for a much greater proportion of total food consumption than its numbers would suggest.

Even among wage-earners, the range of earnings in the early nineteenth century was so large that it is misleading to speak of a single ‘working class’. At the top stood groups of workers in skilled trades unaffected by recent industrialization and forming an elite of labour — compositors, who at the beginning of our period could earn 40s a week and more,5 London tailors with 36s,6 and carpenters with 30s. Other examples of high earnings, all around 30s a week, include shipwrights, bricklayers, masons, and plasterers. Next to the ‘labour aristocracy’ came the ‘new’ skilled trades associated with the factory system and its demands. A Manchester cotton spinner in 1833 made 27s a week, a Durham miner 2s 9d a day; the railways also created remunerative occupations for some hundreds of thousands, a railway mason earning 21s a week in 1843 and a navvy 16s 6d, rising to 33s and 24s respectively in the ‘boom’ year of 1846. Skilled workers in the new metal trades — engineering, boilermaking, and so on — were also sharing in the prosperity of the times with wages of 23s and upwards. In sharp contrast to these two moderately well-paid groups, however, were the large numbers of workers in old hand-trades now in competition with factory production. The handloom-weaver who, at the end of the eighteenth century, stood among the aristocrats of labour with earnings of up to 30s a week, was gradually reduced to a starvation wage of Id an hour as the power-loom took over:7

Wages of a Bolton handloom-weaver

1797 1800 1805 1810 1816 1820 1824 1830 30s 25s 25s 19s 12s 9s 8s 6d 5s 6d

In 1830 there were still 200,000 handloom-weavers in the cotton industry, and more than that in wool: between them, they probably outnumbered all workers in factories at that date. When we add to them the large numbers employed in other depressed hand-trades — the frameworkknitters of Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, earning an average of 5s 3d per week in 1833, the silk-workers of Spitalfields, the Coventry ribbon-makers, the Birmingham nail-makers, the lace-workers, shoe-makers, and seamstresses — we have a vast army of low-paid workers for whom there was as yet no place in factory employments. It was in these still unrevolutionized trades, and in the occupations which were by nature casual and seasonal, such as general labouring and portering, that the greatest poverty lay, and in the period under discussion, these groups greatly outnumbered the factory workers. In the census of 1851, the ten largest occupational groups were in order, agriculture, domestic service, cotton, building, labourers (unspecified), milliners and seamstresses, wool, shoemaking, coal-miners, and tailors, and only two of these (cotton and wool) were partly factory trades. For a minority of the working classes early industrialization brought unexpected wealth, for some it meant little change either way, for many it brought a poverty heightened by the memory of past prosperity. As the century advanced, the wealthy minority grew and the poor majority dwindled, but in the years before the Great Exhibition there were probably at least as many who lost by industrialism as gained by it.

Clearly, then, it is impossible to discuss the diet of town workers as a whole when their earnings ranged from 5s to 40s a week. It is also important to remember that their economic position was affected by other factors which made that position unstable, even precarious. Employment, even for skilled workers, tended to be highly irregular in the early stages of industrialization, so that the same man might alternate between periods of prosperity and poverty in a matter of months or even weeks. Commercial crises and cyclical depressions, which occurred every eight to ten years in the first half of the century, produced widespread unemployment, especially in export trades such as textiles, and half-time working or the com-plete closure of mills for a few months could bring sudden disaster to Bolton, Bury, Leeds, or Bradford, which were virtually dependent on one industry.

Trade cycles resulted in great swings in the purchasing power of the worker between good years and bad. Depressions in the basic industries centred on 1816, 1826–7, 1841–3, and 1848–9, with that of the early 1840s almost certainly the worst of the whole century. John Bright described a procession of 2,000 women and girls through the streets of Rochdale in 1842: ‘They are dreadfully hungry — a loaf is devoured with greediness indescribable, and if the bread is nearly covered with mud it is eagerly devoured.’8 Professor Hobsbawn has noted that while at this time approximately 10 per cent of the whole population were officially classified as paupers, in Bolton in 1842 60 per cent of millworkers were unemployed, 87 per cent of bricklayers, 84 per cent of carpenters, and 36 per cent of ironworkers. Two-thirds of London tailors were out of work and three-quarters of Liverpool plasterers; one in every three of Clitheroe’s population of 6,700 were receiving poor relief, as were one in five of Nottingham’s population, while between 15 and 20 per cent of Leeds inhabitants had an income of less than Is per head per week.9 At such times the problem was to keep body and soul together. For John Castle, an unemployed silk weaver of Colchester, dinner for three was ‘a pennyworth of skimmed milk thickened with flour’,10 while Charles Shaw in the Potteries remembered with bitterness the bread provided for the destitute by the parish, which seemed to be made out of straw, plaster of Paris, and alum:

The crowd in the market-place on such a day formed a ghastly sight. Pinched faces of men, with a stern, cold silence of manner. Moaning women, with crying children in their arms, loudly proclaiming their sufferings and wrongs. Men and women with loaves or coals, rapidly departing on all sides to carry some relief to their wretched homes — homes, well, called such.… The silence froze your heart, as the despair and want suffered had frozen the hearts of those who formed this pale crowd.11

Better than this was the soup provided by Alexis Soyer, the famous chef of the Reform Club, who, after his return from relieving the starving Irish in 1847, opened model soup-kitchens for the destitute weavers of Spitalfields: his recipe costed a quart of soup and a portion of bread at l 5/8d.12

The movement of prices was an additional cause of instability to the town worker. Although the general direction of prices after 1815 was downwards, food remained dear, and the price of bread in particular fluctuated widely within short periods. At a time when up to half the earnings of some working-class families went on bread alone, this was a matter of vital importance. Assuming six 4–lb loaves to be the weekly ration for a family of two adults and three children, which seems to have been typical, the cost of this in London varied as follows:

1830 1835 1840 1845 1850 1855 5s 3d 3s 6d 5s 3s 9d 3s 5d 5s 5d

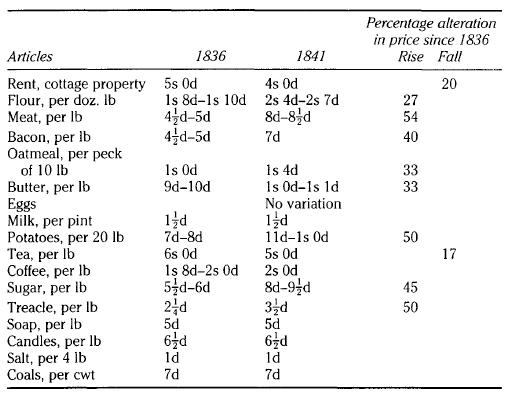

So the man in full employment at 30s a week, and with bread at 1 3/4d a pound, might be affluent, while the same man on half-pay with bread costing 2 ½d a pound could be practically a pauper. Other food prices varied less than bread, but remained high at a time when prices generally, and wages, were falling, so that food was in effect relatively dearer in these years. And at particular times, as between 1836 and 1841, food prices could turn sharply upwards, without any corresponding advance of wages (see Table 5). Tea and house rent were the only items to show a fall during these years, the latter end of which coincided with the worst of the cyclical depressions, with mass unemployment and wage-cuts in the factory districts.

Towns also had important effects on food habits. As we have seen, urban life necessarily meant a greater dependence on the professional services of bakers, brewers, and food retailers generally, partly because living conditions were overcrowded and often ill-equipped for the practice of culinary arts, partly because many women worked at factory or domestic trades and had little time or energy left for cooking. Tenemented houses, occupied by many of the poorer working classes in London and other cities, were rarely supplied with anything more than an open fire for cooking: few weekly tenants could afford the iron cooking-stove with boiler recommended by Francatelli and other food reformers13 which, in any case, became a landlord’s fixture. In this respect, the back-to-back house typical of many northern and midland towns had a distinct advantage: here, a simple cooking-range with oven and water-boiler was usual by the 1830s, and helped to keep alive the tradition of home cooking. Else

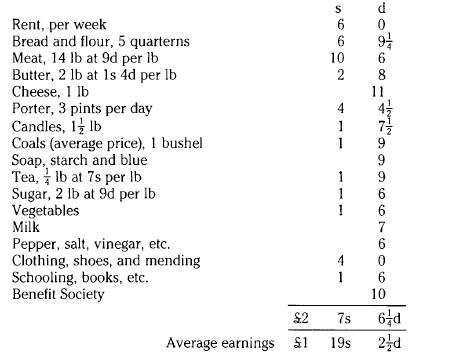

Table 5 Retail prices in Manchester of the following articles of household expenditure in the year 1841, compared with 183614

where, however, the kind of food which most commended itself was that which needed least preparation, was tasty, and, if possible, hot, and for these reasons bought bread, potatoes boiled or roasted in their jackets, and bacon, which could be fried in a matter of minutes, became mainstays of urban diet. Tea was also essential, because it gave warmth and comfort to cold, monotonous food. But roasts and broths, stews and puddings became for many inhabitants of the new towns the Sunday feast, for only on the day of rest were long preparation and cooking possible. The recipe books and manuals of domestic economy written for the poor probably had little influence for this reason: the working classes were not interested, as the Family Economist thought they should be, in how to make a shilling’s worth of meat do for three family dinners by making economical soups and stews, and various dishes made with rice and Indian corn. One recipe ‘for a Good Breakfast, Dinner or Supper’ suggested: ‘Put one pound of rice and one pound of Scotch barley into two gallons of water, and boil them gently for four hours over a slow fire; then add four ounces of treacle and one ounce of salt, and let the whole simmer for half-an-hour. It will produce sixteen pounds of good food.’15 The poor rightly thought little more of this sort of stuff than they did of Count Rumford’s famous soup. Women and children preferred the monotony of bread, potatoes, and weak tea, with occasionally a little butter, cheese, and bacon, to these washy messes which savoured of the workhouse ‘skillee’. What little meat there was was often reserved for the husband’s evening meal, and he might also have a slice of pie, meat, or sausages for his dinner at a coffee stall if he could not get home. It is hard to imagine how men could have borne the long hours which they worked without a diet considerably higher in energy value than that received by the rest of the family.

Many contemporary writers were pessimistic about the effects of the developing factory system on the home life of the working classes, especially where girls and married women were employed and taken away from their domestic duties. For Engels, ‘Family life for the worker is almost impossible under the existing social system.’ A girl who has worked in a factory since the age of nine has never had the chance of acquiring any skill in household duties, he claimed. ‘Consequently, all the factory girls are wholly ignorant of housewifery, and are quite unfitted to become wives and mothers. They do not know how to sew, knit, cook or wash.’16 Such a view seems at odds with the reputation for good home cooking and baking which survived in many of the Lancashire and Yorkshire textile districts. In any case, it is clear that the largest proportion of women employed in textile factories were between the ages of sixteen and twentyone; after that there was a rapid reduction, and the number of wives at work was quite small, varying between about 10 and 25 per cent of the adult women.17 It should also be remembered that where there were several earners in a family the total income compared favourably with that of the very best-paid workers, allowing a quite sufficient expenditure on food, clothing, and domestic comforts generally. Leonard Horner, the factory inspector responsible for the Lancashire district, wrote in his Report for 1837: ‘No unprejudiced observer could come to any other conclusion that in no occupation could there possibly exist among the working people a larger proportion of well-fed, well-clothed, healthy and cheerful-looking people.’18

Another advantage of life in the town was that food could be bought in small quantities (tea and sugar by the ounce, for example) from the shop on the corner. Possibly the most important ‘amenity’ of the early industrial town was the ubiquitous chandler’s shop, willing to tide its regular customers over a crisis by advancing bread and groceries on credit. Of course, the system had its disadvantages. The easy availability of credit meant that many working people went through their lives in debt, their earnings perpetually mortgaged in advance. It also tended to put them at the mercy of unscrupulous shopkeepers, who could overcharge, give short weight, and adulterate the goods of customers who were bound to them by ties of indebtedness. This kind of petty tyranny was the price which many had to pay for a degree of security; people who had no savings and few possessions could scarcely have survived without the chandler’s slate.

A rapid growth in the numbers of shops seems to have kept at least in step with the growth of town populations and, in some cases, to have moved well ahead. In Manchester and Salford, for example, shops selling non-perishable foods increased from 1,000 in 1834 to 4,000 by the early 1870s, while the population scarcely more than doubled.19 Fixed shops were now generally used by the working classes for day-to-day purchases, with markets increasingly reserved for larger, weekend shopping of meat and vegetables. Even here, however, by the 1850s butchers were concentrating their activities into fixed shops. Keen competition was characteristic of food retailing in the towns, where, it was estimated in 1843, prices were between 10 and 25 per cent lower than in rural areas.20 In particular, the middle years of the century saw the emergence of the general store, or corner shop, serving all the food needs of a locality except for fresh meat. The corner shop was especially characteristic of the poorer parts of towns, where it might be the only local shop: in the main shopping streets there was more specialization — between the grocer selling tea, coffee, sugar, dried fruits, spices, and condiments, and the provision dealer in butter, cheese, bacon, ham and eggs.21 Flour was sold by the general grocer, bread by the baker, either over the shop counter or, in better-class districts, by delivery. Grocers and general stores were the most numerous category of all shops by mid-century, closely followed by bakers.22

The practice of employers paying part of the wage in ‘truck’ was an evil which survived well into this period. In view of the high proportion of wage-earners employed by small masters, it seems likely that Huskisson’s estimate — that truck accounted for one-quarter of all earnings — was exaggerated, but we know that it invaded a wide range of employments and was particularly common in some of the heavy industries. A good deal of truck was in the form of food, or of tickets exchangeable for food at the ‘tommy shop’, especially in coal-mining and railway building, where the employer could claim that he was providing a service in areas ill-supplied with shops. Obviously, there existed here a golden opportunity for fraud of all kinds, and the complaints of the Barnsley miners in 1842 that they were forced to take ‘provisions of the worst quality and at prices far above the market’ are echoed throughout contemporary literature. In the areas where it was widespread, truck had important effects in reducing real wages by non-competitive pricing, and the frequency with which the practice was investigated by Parliament, and legislation passed against it, suggests that it continued to cause much concern to what was supposedly a ‘free economy’. As late as 1871 the Commission on the Truck System found it to be still common in colliery districts, iron works, railway building, and some workshop industries such as nail-making.23

Once the day’s work had begun in factory or foundry, mine or workshop, there was little pause for food or rest in what seem to us unbelievably long hours of labour. The saddest case of all in a sad history of industrial feeding was that of the pauper children who were, in the early part of the century, ‘apprenticed’ by parish authorities to mill-owners in the north and became slaves in all but name for seven or fourteen years. Robert Blincoe, who wrote a personal memoir on life as a parish apprentice, spoke of the diet as ‘the scantiest share of coarsest food capable of supporting animal life’:

The store pigs and the apprentices used to fare very much alike; but when the swine were hungry, they used to grunt so loud they obtained the wash first to quiet them. The apprentices could be intimidated and made to keep still. The fatting pigs fared luxuriously compared with the apprentices. They were often regaled with meal balls, made into dough, and given in the shape of dumplings.

He went on to say that he and others who worked in a part of the factory near the pigsties used to keep a sharp eye on the fatting pigs and their meal balls, and as soon as the swineherd withdrew Blincoe would stealthily slip down, plunge his hand in at the loop-holes, and steal as many dumplings as he could grasp:

The pigs, usually esteemed the most stupid of animals, learned from experience to guard their food by various expedients; made wise by repeated losses, they kept a keen look-out, and the moment they ascertained the approach of the half-famished apprentices, they set up so loud a chorus of snorts and grunts, it was heard in the kitchen, when out rushed the swineherd armed with a whip, from which means of protection for the swine this accidental source of obtaining a good dinner was soon lost! Such was the contest carried on for some time at Litton Mill between the half-famished apprentices and the well-fed swine.24

A woman who knew at first hand the conditions in an ‘apprentice house’ where the children were boarded testified that they

were fed chiefly on porridge, which was seasoned with beef and pork brine, bought at the Government stores, or those of contractors — the ‘bottoms’ of casks supplied to the Navy. This nauseous mixture was sometimes so repulsive even to the hungry stomachs that it was rejected… . They were fed out of troughs, much resembling those used by pigs.25

Pauper ‘apprentices’ were, fortunately, a very small proportion of the factory population, and the practice did not continue after the reform of the Poor Law in 1834. Ordinary factory workers, adults and children, provided their own food, which they ate during the permitted breaks. These, it is true, were often much too short before the Factory Act of 1833 laid down some statutory minima. A witness before Michael Sadler’s Committee on Factory Children’s Labour of 1831 said that he was seven when he started work: the hours of labour were 5 a.m. to 8 p.m. with half an hour allowed at noon. ‘There was no time for rest or refreshment in the afternoon; we had to eat our meals as we could, standing or otherwise. I had 14} hours actual labour when seven years of age: the wage I then received was two shillings and ninepence per week.’ This witness explained that the dust in the atmosphere often got into the food and spoiled it. ‘You cannot take food out of your basket or handkerchief but what it is covered with dust directly… . The children are frequently sick because of the dust and dirt they eat with their meal.’26 This was probably the extreme case. At ‘good’ mills there was an hour for dinner at noon, half an hour for breakfast, and another half-hour for ‘drinking’ in a day starting at 6 a.m. and ending at 8 p.m., but in a great many factories up to half the total mealtimes might be taken up in cleaning the spindles.27 ‘The child snatches its meal in a hurried manner in the midst of work, and in a place of dust — in a foul atmosphere and in a temperature equal to a hothouse.’ Conditions in the coal-mines were even worse. The Royal Commission of 1842 revealed that:

Of all the coal districts in Great Britain there are only two (South Staffordshire and the Forest of Dean) in which any regular time is usually set apart for the rest and refreshment of the workpeople during the day…. In the great majority of the coal districts of England, Scotland and Wales no regular time whatever is even nominally allowed for meals, but the people have to take what little food they eat during their long hours of labour when they best can snatch a moment to swallow it.28

There were, even in the early nineteenth century, some ‘model employers’ who recognized the importance of adequate diet for their employees and were pioneers of industrial welfare generally. Samuel Oldknow at Mellor Mill, although working his apprentices for long hours, fed them almost lavishly with porridge and bacon for breakfast, meat every day for dinner, puddings or pies on alternate days, and, when pigs were killed, pies which were full of meat and had a short crust. All the fruit in the orchard was eaten by the children. He also organized supplies of necessary foods for his adult workpeople, rearing bullocks, keeping a herd of dairy cows and a market garden of three acres to supply fresh vegetables.29 When factories or mines were established in rural areas, remote from shops and ill-served by communications, some provision of this kind was essential, but Oldknow and others were exceptional in regarding such services as a duty, dissociated from any idea of profit. The London Coal Company, for example, provided its workers on Tyneside with wheat, rye, and other grain at cost price, and in fact put itself considerably out of pocket by paying the heavy transport charges. At one point it bought an old lead mill at Tynebottom, and refitted it as a corn mill to supply the whole district, so breaking the exorbitant charges of the local millers.30 The most outstanding example of an enlightened employer was, of course, Robert Owen during his management of the New Lanark cotton mills from 1799 to 1824. Dr Henry MacNab, visiting this model community numbering over 2,000 in 1819, described the spacious kitchens, bake-house, and store-rooms, the dining-room, 110 ft by 40 ft, in which employees could, if they wished, take all their meals at very moderate cost, and the vegetable garden which was granted to every householder. Owen also provided a shop selling provisions and clothing of the best quality at little more than cost price. ‘In one of our walks we met a woman with a choice piece of beef purchased at the establishment. She told us that she had paid only 7d per pound, and that she could not have bought it under lOd in Glasgow market.’31

Owen’s great underlying purpose was to improve human character, to change the labour-force which he inherited at New Lanark — poor, ignorant, given to vice and drunkenness — into an efficient, honest, and happy community. Few employers in the early nineteenth century had any such moral concern, though one of the most widely held attitudes about working people was that they were extravagant and improvident, that their incomes would be quite adequate for their needs if only they were laid out economically and not squandered on expensive foods and drink. Dr Andrew Ure, writing in 1835 on the condition of cotton operatives, ascribed the gastralgia from which many of them suffered to their preference for highly flavoured food, and in particular their fondness for ‘rusty’ bacon. ‘In this piquant state it suits vitiated palates accustomed to the fiery impressions of tobacco and gin.… Hypochondriasis, from indulging too much the corrupt desires of the flesh arid the spirit, is in fact, the prevalent disease of the highest-paid operatives.’32 As well as condemning alcohol, the doctor deprecated the use of tea and milk because of their impurity: it is not clear from his account what factory workers should drink, if anything. At a somewhat earlier period Hannah and Martha More had expressed similar disgust at the luxurious way of life of glassworkers in the Mendips, especially those living in the village known locally as ‘Little Hell’.

Both sexes and all ages herding together; voluptuous beyond belief … the body scarcely covered, but fed with dainties of a shameful description. The high buildings of the glass-houses ranged before the doors of the cottages — the great furnaces roaring — the swearing, eating and drinking of these half-dressed, black-looking beings, gave it a most infernal and horrible appearance. One, if not two joints of the finest meat were roasting in each of these little hot kitchens, pots of ale standing about, and plenty of early, delicate-looking vegetables.33

A somewhat more sympathetic account of occasional indulgence at work is given by Charles Shaw, who had worked as a potter’s boy in Staffordshire in the 1840s. At ten years old he worked from four or five in the morning until nine or ten at night on the most meagre fare: ‘Bread and butter was made up in a handkerchief, with a sprinkling of tea and sugar. Sometimes there was a little potato pie, whith a few pieces of fat bacon on it to represent beef. The dinner-time was from one till two o’clock and from then until nine or ten the weary workers got no more food.’ It is scarcely surprising that, working in a temperature approaching that of the ovens, the potters brought in ale to their work, and occasionally stayed on drinking through the night. ‘It was easy to cook, with a stove in each shop. A sheep’s pluck and onions was a favourite dish. Sometimes ropes of sau-sages would be sent for.’34 The potters seem moderate compared with the glassworkers and their ‘delicate-looking vegetables’.

Possibly there was something in the industrial environment which predisposed workers to indulgence when the opportunity presented itself, but there was nothing new in the alternation of feasting with fasting. This had been the rural pattern for centuries, and like much else was merely carried over into life in the new towns. Probably the extent of drinking did not increase either, although it became more evident, and more exposed to public criticism, in the town. The surprising fact is that per capita beer consumption fell continuously throughout the first half of the nineteenth century (see Table 4, page 17), at a time when drinking can hardly have been more attractive and despite the Beerhouse Act of 1830 which greatly increased its availability. The estimated national drink bill was high enough by any standard:35

|

Year |

Total cost (thousands of pounds) |

Cost per head £ s d |

| 1820 | 50,441 | 2 8 6 |

| 1825 | 67,027 | 2 19 5 |

| 1830 | 67,292 | 2 16 5 |

| 1835 | 80,528 | 3 3 0 |

| 1840 | 77,606 | 2 18 10 |

| 1845 | 71,632 | 2 12 11 |

1850 |

80,718 |

2 18 10 |

An expenditure on drink of nearly £3 a year for every man, woman, and child in the country — £15 or so for every househould — was certainly enough to keep many families poor, and to make some destitute. Again, average statistics are misleading. With the growth of the Temperance Movement after 1830, some families gave up drink completely, but others continued to spend one-third or one-half of all their earnings on it. It is easy to condemn the waste, poverty, crime, and disease which were unquestionably caused by alcohol; it is also important to remember its attractiveness at this period. The public house was warmer, more comfortable and more cheerful than the home usually was, and it provided quick escape for men and women who were too tired and too uneducated for intellectual pursuits and were not given the time or the facilities for constructive leisure activities. Many work customs traditionally involved drinking — the ‘footings’ of apprentices, the celebrations when a man had served his time, got married, or had a child, the annual ‘weighgoose’ and other holiday festivities. But the fatigue and heat of some occupations such as mining, iron-moulding, dock labouring or pottery work required large quantities of body fluid to be replaced by liquid of some kind, and given the relative cheapness of beer and the scarcity of pure water in many areas, it is not surprising that beer was often preferred.36 The harrowing scenes described by Charles Shaw in the Potteries in the 1840s — of wages not paid out until Saturday night in a public house, of wives desperately trying to coax their husbands home before all was spent, and of men who, despite their entreaties, continued drinking until the following Tuesday37 — were reproduced on a lesser scale in many English industrial towns.

Actual budgets and biographical accounts of meals left by working people are, unfortunately, all too few. The worker or his wife rarely kept household accounts, and we have to rely to some extent for a picture of urban diet on calculations which were made for specific purposes — by the worker in order to demonstrate his need for higher wages, by middle-class writers on domestic economy in order to show him how he ought to lay out his earnings. Some of the following budgets may, therefore, be nearer the ‘ideal’ than the ‘actual’, although the close agreement between many of them suggests that they are probably very near to reality. They are arranged chronologically, and illustrate all levels of earnings.

In 1810, the London compositors, probably the highest paid of all artisans, submitted a claim to their employers for an increase in view of the rising cost of living. Their wages at that time varied, according to whether they were engaged on reprint or manuscript work, from £1 17s 6d to £2 0s 9d a week. In order to substantiate their claim for higher wages, they compiled a typical weekly budget for a compositor, his wife and (small) family of two children:38

This was affluence approaching middle-class standards. The heavy expenditure on meat, rent, and clothes, and the inclusion of items for education and insurance are particularly interesting.

This budget makes a startling comparison with that prepared nine years later by the Nottinghamshire framework-knitters during their negotiations for higher rates of pay. In the preceding years, especially during the Luddite rising of 1811–12, there had been frequent hunger riots and attacks on the shops of bakers, butchers, and greengrocers. In 1819 a petition was presented to the Lord Lieutenant of the County which recited:

From the various and low prices given by our employers, we have not, after working from sixteen to eighteen hours per day, been able to earn more than from four to seven shillings per week to maintain our wives and families upon, to pay taxes, house rent, etc…. and though we have substituted meal and water, or potatoes and salt for that more wholesome food an Englishman’s table used to abound with, we have repeatedly retired after a hard day’s labour, and been under the necessity of putting our children supperless to bed to stifle their cries of hunger; nor think that we give this picture too high a colouring when we can most solemnly declare that for the last eighteen months we have scarcely known what is to be free from the pangs of hunger.39

This was the poverty-line diet, the irreducible minimum which was as bad as anything that the poorest agricultural labourer experienced. It could apply as well to 1819 as to 1850, perhaps the only difference being that at the earlier date the diet of oatmeal or potatoes was still resented as a recent and unusual innovation, whereas, by 1850, it had become accepted by many as normal. Geography, of course, played an important part in determining the diet of the poorest. When William Lovett was living with his grandmother in Cornwall on 5s a week, ‘our food consisted of barleybread, fish and potatoes, with a bit of pork on Sundays’.40 The Lovetts were lucky to live on the sea-coast, where cheap fish abounded. In an inland town like Nottingham, a red herring was an occasional luxury to add flavour to the dinner.

Between these two extremes of wealth and poverty, the compositors and the framework-knitters, lay the middle stratum of skilled workers and factory operatives, with earnings of £1 a week and upwards. Mrs Rundell, whose System of Practical Domestic Economy was the best-selling cookery book of the first half of the nineteenth century, gave two suggested budgets for incomes of 33s and 21s a week respectively (Table 6). Both are for a family of husband, wife, and three children — still small by contemporary standards. Mrs Rundell notes that:

We have, in this Estimate, taken the expense of each child at one shilling and ninepence per week; and though a child in arms will not cost so much, yet the expense of lying-in will be fully equivalent. After the third child, the wife will naturally cause the oldest to attend to the youngest, and by that means gain time for other purposes.… Besides, in manufacturing neighbourhoods children are taught at an early age to earn something towards their own support. These and similar circumstances will tend to counter-balance such dilemmas as may arise, that would otherwise be disheartening.

Both are ‘ideal’ budgets for skilled workers in regular employment and with less than average-size families. It is interesting that even on 21s a week the family is supposed to dispense with tea and ‘incidents’, and to make do with cheap cuts of meat. This lower budget can be compared with that of a Northumberland miner in the next year, 1825, given in an anonymous pamphlet, A Voice from the Coal Mines. The man’s earnings average &2 a fortnight, but deductions for fines, rent, and candles bring it down to 30s or 15s a week. Again the family is of three children:

s d Bread, 2 ½ stone at 2s 6d per stone 6 3 1 1b butcher’s meat a day at 7d a 1b 4 1 2 pecks potatoes at 1s per peck 2 0 Oatmeal and milk for 7 breakfasts at 4 ½d each morning

2 8

15s 0d

The family need as well to produce comfort:

Table 6 Mrs RundeWs budgets for a husband, wife, and three children, 182141

Is this too much, asks the writer? He replies that colliers would die if they did not take their children to work fourteen hours a day as soon as they could walk.42

Even so, it is doubtful whether he could have made good the 11s deficit, and in all probability he had to sacrifice a good deal of his pound of meat a day. The factory worker on a comparable wage, according to Dr James Kay, received little or no fresh meat. Describing the daily life of a Manchester operative in 1832, Kay says that he rose at five o’clock in the morning, worked at the mill from six till eight, and then returned home for half an hour or forty minutes to breakfast. This consisted of tea or coffee with a little bread. He then went back to work until noon. At dinner-time, the meal for the inferior workmen consisted of boiled potatoes, with melted lard or butter poured over them and sometimes a few pieces of fried fat bacon. Those with higher earnings could afford a greater proportion of animal food, though the quantity was still small. Work then resumed from one o’clock until seven or later, and the last meal of the day was tea and bread, sometimes mingled with spirits.43

A few years later, in 1841, S. R. Bosanquet quoted Dr Kay as saying ‘England is the most pauperized country in Europe’. Bosanquet was writing a frankly propagandist work on The Rights of the Poor, but his examples, harrowing as they are, were fully authenticated. After citing a number of recent deaths in London caused by starvation — men and women who had died in the streets or shortly after admission to a workhouse — he quotes extensively from Dr Howard’s essay on The Morbid Effects of Deficiency of Food, written after some years as a surgeon at the Royal Infirmary and the Poor-House at Manchester:

The public generally have a very inadequate idea of the number of persons who perish annually from deficiency of food… . Although death directly produced by hunger may be rare, there can be no doubt that a very large proportion of the mortality amongst the labouring classes is attributable to deficiency of food as a main cause, aided by too long continued toil and exertion without adequate repose, insufficient clothing, exposure to cold and other privations to which the poor are subjected.44

Bosanquet himself quotes a number of weekly budgets of London families where the man is in full work, saying, ‘They will furnish a standard from which to estimate the condition of larger families, or of families where, from illness, or other causes, the expenses are increased or the employment is irregular.’ With earnings of 30s a week and upwards, a skilled London workman could live in reasonable comfort:

Richard Goodwin, 45 Great Wild Street: a wife and five children:

s d 2 oz tea 8 7 oz coffee 10 ½ 3 1b sugar 1 9 1 cwt coals, ½ bushel coke, wood 2 3 12 loaves at 8d 8 0 18 1b potatoes 9 1½ 1b butter 1 6 1 lb soap, ½1b soda 7 Blue and starch 2 Candles 7 Bacon 2 6 Greens or turnips, onions, etc. 6 Pepper, salt, and mustard 3 Herrings 9 Snuff 6 Rent 4 0 Butcher’s meat, 6d a day 3 6 £1 9s 1 ½d

With earnings of 21s a week, nearly all the above items had to be drastically reduced — bread to seven loaves, bacon to Is, and so on — and at 15s a week, the wage of a labourer in regular employment, Bosanquet thought it just possible for a man, wife, and three children to exist. This probably represents a fairly typical semi-skilled worker’s budget of the period:45

s d 5 4–1b loaves at 8½d 3 6 ½ 5 lb meat at 5d 2 1 7 pints of porter at 2d 1 2 ½ cwt coals 9 ½ 40 1b potatoes 1 4 3 oz tea, 1 1b sugar 1 6 1 1b butter 9 ½ 1b soap, ½ lb candles 6 ½ Rent 2 6 Schooling 4 Sundries 5 ½ 15s 0d

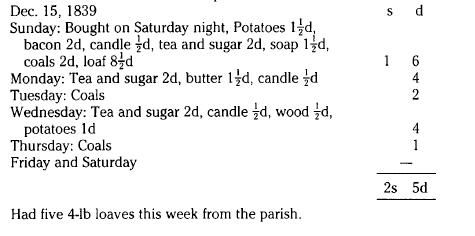

The pint of porter a day is hardly extravagant, nor the cheap meat at 5d a pound; 2s 6d rent would provide one room, or at best two, and there is nothing here for vegetables — other than potatoes — for milk, clothing, or medicine. But sickness or widowhood could easily shatter even this frail standard of life. Elizabeth Whiting, a forty-year-old widow, had four young children to provide for:46

6 Cottage Place, Kenton Street — Pays 3s a week rent, owes £1 13s. Does charing and brushmaking; earned nothing this week; last week 3s; the week before 5s 8d.

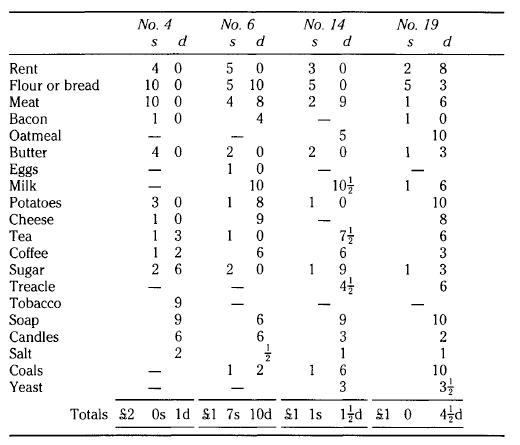

Expenditure

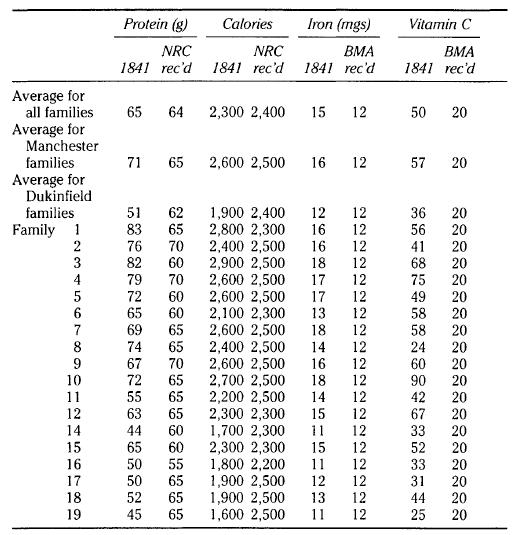

In the same year, 1841, a detailed survey of the earnings and expenditure of nineteen working-class families in Manchester and Dukinfield was made on behalf of the Mayor, William Neild, for the Statistical Society. This was a particularly valuable record, because it gave in complete detail and from the personal statements of the people concerned a precise account of the condition of workers in the cotton industry. The first twelve cases were Manchester families ‘selected because they were of sober and industrious habits. Their employment, also, during the general depression which has for some time existed in the trade of this district, has been almost uninterrupted, and their weekly wages have remained the same.’ These were exceptionally fortunate families. The remaining seven cases were of Dukinfield families, who, like the majority of cotton workers at this time, had suffered reductions in their earnings, and were, therefore, more typical of the general state of Lancashire. We give four of the nineteen cases — nos 4 and 6 as examples of moderately comfortable families from Manchester, nos 14 and 19 as more representative Dukinfield families. All are skilled workers. No. 4 is a storeman, with eight in the family and a high total income of £2 17s or 7s 1l ½d per head: no. 6 is an overlooker, six in family, with an income of £1 14s or 5s 8d each: no. 14 is a dresser with the same size of family, an income of £1 4s or 4s each, and no. 19 a mechanic’s assistant with 16s or only 2s 3d each for the family of seven.

The last family was accumulating debt at the rate of 4s a week, despite its very modest expenditure on such things as meat and tea: indeed, six out of

the seven Dukinfield families were in debt to local shopkeepers. Apart from this, the most interesting point in the budgets is the increased propor-tion of earnings spent on bread, and the decreased proportion on butcher’s meat, as the income falls. The amounts, expressed as percentages of total income, are as follows:

| On bread | On meat | |

| Case no. 4 | 17.5 | 17.5 |

| Case no. 6 | 16.9 | 13.8 |

| Case no.14 | 20.8 | 11.4 |

| Case no. 19 | 32.8 | 9.4 |

This was the observation accurately made by Engels in his Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844:

The better-paid workers, especially those ip whose families every member is able to earn something, have good food as long as this state of things lasts; meat daily, and bacon and cheese for supper. Where wages are less, meat is used only two or three times a week, and the proportion of bread and potatoes increases. Descending gradually, we find the animal food reduced to a small piece of bacon cut up with the potatoes; lower still, even this disappears, and there remains only bread, cheese, porridge and potatoes until, on the lowest round of the ladder, among the Irish, potatoes form the sole food.47

On the evidence of the Manchester survey, the amount spent on oatmeal increased similarly and that on butter, cheese, sugar, and tea fell. The poorer the family, the greater the dependence on cheap, carbohydrate foods, and the smaller the intake of proteins. There is only one redeeming feature in no. 19’s budget — the very sensible expenditure of Is 6d a week on milk.48

The Neild budgets have been analysed by J.C. McKenzie and evaluated in present-day nutritional terms (see Table 8). It will be seen that only the best paid of the regularly employed workers achieved a diet which would now be regarded as adequate for health in calories and protein; all but one of the Dukinfield families were seriously below the recommended allowances, the inference being that the male wage-earner, who would have needed some 2,800–3,000 calories a day for moderate work, took a larger share of the available food at the expense of his wife and children. The effects of such low diets would tend to be restricted physical growth and rickets in children, susceptibility to certain diseases such as tuberculosis and gastro-intestinal fevers, anaemia in women and, at times of crisis, epidemic diseases such as typhus, the so-called ‘famine fever’.

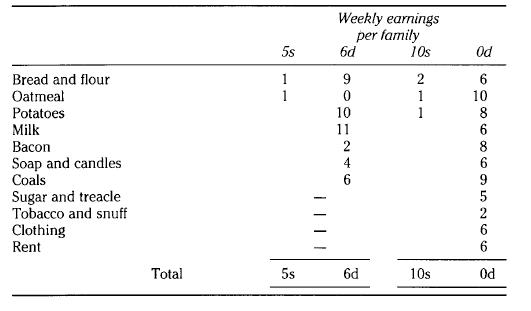

All the families in the Statistical Society’s survey were of skilled workers, and all were in employment. For budgets of poorer workers we have to turn to an inquiry made by Alexander Somerville, who spent the spring and summer of 1842 touring the manufacturing areas of the north in an effort to show that the depressed state of agriculture was due to the lack of purchasing power of the industrial population. Accrington, for example, was engaged almost exclusively in the cotton trade: of the 3,738 workers in the town, only 1,389 were fully employed in 1842 at an average wage of 8s 8d per week; 1,622 were partly employed at 4s lOd each and 727 were totally unemployed and destitute. An employer told him that in 1836 he paid his block printers 17s a week, now not quite 6s. ‘Need you be told’, asked Somerville, ‘that with 17s there would be loaf-bread and butchemeat and cheese and butter used, while with 6s there can be little more than oatmeal gruel, potatoes and salt.’49 In the course of his survey he collected a large number of budgets from families, each consisting of the parents and four children, and these were then averaged to represent weekly incomes of 5s 6d, 10s, 15s 6d, and 25s 6d. The two lowest are given since the higher ones correspond closely to those in the Statistical Society’s survey (see Table 9).

Only in the two higher categories was anything available for meat or butter, cheese or beer, and it is interesting to find that even tea has been

Table 8 William Neild’s Manchester and Dukinfield budgets, 184150

Note:

1 Family 13 is not used due to insufficient information.

2 Appropriate allowances are made in the calculations for the differing nutritional needs of men, women, and children.

3 NRC = National Research Council of the US, recommended daily allowances.BMA = British Medical Association,, recommended daily allowances.

squeezed out in the lower budgets. Again, the considerable expenditure on milk, long before its nutritional properties were known scientifically, is the saving feature of the 5s 6d budget.

The real question is, of course, how many families fell into the 5s 6d and 10s categories and how many were in the comparatively comfortable

circumstances of the Manchester families? There can be no exact answer to this, because, for the reasons previously given, the fortunes of a family could fluctuate greatly from one year to another. As Somerville said, ‘When trade was in a thriving condition, by far the greatest proportion of families belonged to this fourth class (26s 6d a week), a smaller proportion to the third (15s 6d), and comparatively few to the second or first. Now in 1842, when trade is prostrate, the greatest proportion of families belong to the first and second classes, and comparatively few to the third and fourth.’ It must also be remembered that in this period of incomplete industrialization, there were as many unskilled as skilled workers whose earnings were permanently in Somerville’s first and second categories.

1842 was, admittedly, a ‘bad’ year, but in the decade of the forties there were as many ‘bad’ years as good. Prosperity returned briefly from 1843 to 1845, but 1846 saw a railway crisis, the great Irish potato famine and renewed depression in a number of major industries. In 1847, when provincial banks failed and alarm was even felt for the Bank of England, Alexis Soyer headed a public subscription for soup-kitchens for the starving during yet another cyclical depression. Only after 1848 were there signs of that settled and expanding prosperity which, in retrospect, has been called ‘The Golden Age’: a period when, for the first time, all grades of industrial workers began to share significantly in the fruits of industrialization; 1848 rather than 1850 marks the end of the hungry halfcentury, the period when the diet of the majority of town-dwellers was at best stodgy and monotonous, at worst hopelessly deficient in quantity and nutriment. Almost half the children born in towns died before they reached the age of five, and a high proportion of those who did survive grew up ricketty, deformed, and undernourished. The long-term effects of this physical degeneration were only demonstrated many years later in the Boer War and the First World War, when medical examinations revealed the mass unfitness of urban recruits. The ‘C3 nation’ which so disturbed the public conscience in 1918 had its origins in the dietary inadequacy of the early nineteenth century.

By 1850 a distinctive urban, working-class dietary pattern was in the process of emerging. In earlier decades of the century it had not been markedly different from the rural pattern, with the same dependence on basic foods such as bread, potatoes, bacon, cheese, and butter, all of which were either processed foods or foods which had a lengthy marketing and storage period. Perishable foods like fresh vegetables, fruit, milk, fish, and meat were severely limited by transport difficulties before the railway age, and were therefore expensive. As previously demonstrated, income had a direct and major influence on choice, the poorer working classes being restricted to a narrow range of mainly starchy foods providing cheap sources of energy. Town workers were necessarily more dependent on commercially made products (bread was the first, and most important, ‘convenience food’) bought at shops and markets, and rarely had the opportunity of supplementing their diet from home-grown sources. But, for the better-off worker, towns by mid-century offered a greater variety of foods, both fresh and prepared, than was available in the countryside, and the opportunity to indulge in what had formerly been regarded as luxuries: in particular, the average consumption of meat, fats, sugar, and milk by the sort of people represented by the Neild budgets was greater than that of rural workers half a century earlier,51 as was that of fish, tea, and coffee. A trend towards increased consumption of fats and sugar, and an increased use of mildly stimulating beverages, was already becoming apparent by mid-century, and indicative of the kinds of food choices more people would make as resources became available.

Notes

1 Translated by W.O. Henderson and W.H. Chaloner (1958), 10.

2 Porter, G.R. The Progress of the Nation (1847 edn), 78.

3 See, for example, the writings of A. Toynbee, S. and B. Webb, J.L. and Barbara Hammond, and G.D.H. Cole.

4 See, for example, the writings of J.H. Clapham, I. Pinchbeck, T.S. Ashton, and W.H. Chaloner.

5 Howe, Ellic (ed.) (1947) The London Compositor. Documents relating to Wages, Working Conditions and Customs of the London Printing Trade, 1785–1900, 163.

6 Wood, George H. (1900) A Glance at Wages and Prices since the Industrial Revolution.

7 Porter, op. cit., 457.

8 Quoted by Norman McCord (1958) The Anti-Corn Law League, 127.

9 Hobsbawm, E.J. (1975) The British standard of living, 1790–1850‘, in Arthur J. Taylor (ed.), The Standard of Living in Britain in the Industrial Revolution, 69–71.

10 The Autobiography of John Castle (1819–1889), quoted in John Burnett (ed.) (1982) Destiny Obscure. Autobiographies of Childhood, Education and Family from the 1820s to the 1920s, 57, 262–9.

11 Shaw, Charles (1903) When I Was a Child, repub. 1977, 42–3.

12 Volant, F. and Warren, J.R. (eds) (1859) Memoirs of Alexis Soyer, repub. 1985, 110–28.

13 Francatelli, Charles Elme (1852) ,A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes, repub. 1977, 9–10. Francatelli was formerly maître d’hôtel and chief chef to the Queen.

14 Neild, W. (1841) ‘Comparative statement of the income and expenditure of certain families of the working classes in Manchester and Dukinfield, in the years 1836 and 1841’, Journal of the Statistical Society of London IV, 322.

15 The Family Economist. A Penny Monthly Magazine devoted to the Moral, Physical and Domestic Improvement of the Industrious Classes I (1848) 147.

16 Engels, Friedrich (1845) The Condition of the Working Class in England, trans. W.O. Henderson and W.H. Chaloner (1958), 145, 165–6.

17 Pinchbeck, Ivy (1930/1985) Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750–1850, 197.

18 Quoted in Pinchbeck, ibid., 311.

19 Scola, R. (1975) ‘Food markets and shops in Manchester, 1770–1870’, Journal of Historical Geography 1, 153–68.

20 Barker, T.C. (1966) ‘Nineteenth century diet: some twentieth century questions’, in T.C. Barker, J.C. McKenzie, and John Yudkin (eds) Our Changing Fare. Two Hundred Years of British Food Habits, 21.

21 Blackman, Janet (1976) ‘The corner shop: the development of the grocery and general provisions trade’, in Derek J. Oddy and Derek S. Miller (eds) The Making of the Modern British Diet, 148–61.

22 Alexander, D. (1970) Retailing in England during the Industrial Revolution, 18–25.

23 Hilton, G.W. (1960) The Truck System.

24 Brown, John (1832) A Memoir of Robert Blincoe, an Orphan Boy.

25 ‘Alfred’ (Samuel Kydd) (1857) The History of the Factory Movement, from the year 1802 to the enactment of the Ten Hours’Bill in 1847 1, 25.

26 Reports from the Select Committee on the Bill for the Regulation of Factory Children’s Labour (Sadler’s Committee), 1831–1832, XV: Evidence of Joseph Haberjam.

27 A Sketch of the Hours of Labour, Mealtimes, etc. etc. in Manchester and Its Neighbourhood (1825).

28 Children’s Employment (Mines), Royal Commission, First Report (1842) (380), XV.

29 Unwin, George (1924) Samuel Oldknow and the Arkwrights, 173 et seq.

30 Raistrick, Arthur (1938) Two Centuries of Industrial Welfare (Supplement No. 19 to the Journal of the Friends‘ Historical Society).

31 Quoted in Sir Noel Curtis-Bennett (1949) The Food of the People: being the History of Industrial Feeding, 153. et seq.

32 Ure, Andrew (1861) The Philosophy.of Manufactures, or an Exposition of the Scientific, Moral and Commercial Economy of the Factory System (3rd edn), 385–7.

33 Roberts, Arthur (ed.) (1859) Mendip Annals; or a Narrative of the Charitable Labours of Hannah and Martha More (3rd edn), 61–2.

34 Shaw, op. cit., 52–5.

35 Calculated from William Hoyle (1871) Our National Resources, and How They are Wasted. An omitted chapter in Political Economy, series continued in Hoyle and Economy (1887).

36 Harrison, B. (1971) Drink and the Victorians. The Temperance Question in England, 1815–1872.

37 Shaw, op. cit., chap. VIII, 67 et seq.

38 Howe, op. cit., 163.

39 Modern Nottingham in the Making, quoted by J.D. Chambers (1945), 32.

40 The Life and Struggles of William Lovett in his pursuit of Bread, Knowledge and Freedom (1876), 13.

41 Rundell, Mrs (1824) A System of Practical Domestic Economy (new edn).

42 Anon (1825) A Voice from the Coal Mines, quoted in J.L. Hammond and Barbara Hammond (1917) The Town Labourer, 1760–1832, 34–5.

43 Kay, James Phillips (1832) The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes Employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester.

44 Bosanquet, S.R. (1841) The Rights of the Poor and Christian Almsgiving Vindicated, 51–2.

45 ibid., 91 et seq.

46 ibid., 101–2.

47 Karl Marx and Frederick Engels on Britain (1953), 107.

48 Neild, op. cit., 323 et seq.

49 Somerville, Alexander (1843) A Letter to the Farmers of England on the Relationship of Manufactures and Agriculture by One who has Whistled at the Plough, 4.

50 Adapted, by kind permission, from J.C. McKenzie (1962) The composition and nutritional value of diets in Manchester and Dukinfield in 1841‘, Transactions of Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society 72, 123–40.

51 Oddy, D.J. (1983) ‘Diet in Britain during industrialization’, paper presented at Leyden Colloquium, The Standard of Living in Western Europe (September), II (Table 2).