8

8

Urban England: poverty and progress

Most observers of the social scene in the middle of the last century were still uncertain whether the rapidly developing industrialization of Britain was benefiting or deteriorating the lot of the worker. In the depressed years of the early 1840s few were in doubt. Samuel Laing, whose essay on National Distress was awarded first prize in a competition in 1844, believed that:

Society has been startled by the discovery of a fearful fact, that as wealth increases, poverty increases in a faster ratio, and that in almost exact proportion to the advance of one portion of society in opulence, intelligence and civilization, has been the retrogression of another and more numerous class towards misery, degradation and barbarism.1

It was not difficult to support his gloomy contention by a mass of statistical information recently made available by Parliamentary Blue Books and the researches of private social investigators. In 1841 more than 8 per cent of the population of England and Wales were officially classed as paupers, and this at a time when the New Poor Law had determined to reduce pauperism by attaching the most unpalatable conditions to relief. In Manchester more than half of the inhabitants required the assistance of public charity in bringing their offspring into the world; in Leeds more than one-third of the whole adult population had no regular employment, while over large areas of the industrial north and midlands wages in the old craft industries were depressed to an impossibly low level. By the 1840s Lancashire handloom-weavers could earn no more than 4s 11 V2& per family per week, and their lot was paralleled by that of the Coventry ribbon-weavers, the Yorkshire linen-weavers, and the Nottinghamshire framework-knitters. These were the multitudes who inhabited back-to-back slums in narrow courts and alleys or, less fortunate still, shared rooms and even cellars in overcrowded tenements, the squalor of which was only now being exposed by the sanitary reports of Edwin Chadwick.2 Those who had employment in the new factories and mines were certainly better off, but they were as yet a minority of the labouring population — of those employed in cotton factories, for example, only a quarter were males over eighteen years of age, the rest being women and children whose earnings were pitifully small. Laing in 1844 summarized the effects so far of the introduction of machinery on the worker:

About one-third plunged in extreme misery, and hovering on the verge of actual starvation; another third, or more, earning an income something better than that of the common agricultural labourer, but under circumstances very prejudicial to health, morality, and domestic comfort — viz. by the labour of the young children, girls, and mothers of families in crowded factories; and finally, a third earning high wages, amply sufficient to support them in respectability and comfort.3

Generalized assessments of this kind can be enriched by first-hand evidence of the lives of working people.4 One such autobiography describes the early life of Thomas Wood, who was born at Bingley in Yorkshire in 1822, the eldest of a family of five of a respectable, hard-working handloom-weaver.5 Thomas was evidently an intelligent boy who, after learning to read the first chapter of St John’s Gospel at a little private school, went at the age of six to Bingley Grammar School, through the influence of his grandfather with the vicar, Dr Hartley. Here he learnt Latin grammar and writing free, though his parents paid 1s 6d a quarter to the school for fire and cleaning. After only two years he had to leave to wind bobbins at home for his father, and, thereafter, Sunday school was the only formal education Thomas received; after the School Feast in 1831, when the children had marched round the town for two-and-a-half hours, they were regaled with half a gill of beer and half a teacake. Shortly after this he went to work at the mill from 6 a.m. to 7.30 p.m., with forty minutes allowed for dinner, at a wage of 1s 6d per week: ‘Small as it was, it was a sensible and much needed acquisition for the family store.’ Here he stayed for five years, until, at thirteen, his father resolved that Thomas should be taught a trade, and he was apprenticed to a local mechanic. To do this was a great sacrifice for the family; by the time he had worked out his apprenticeship at twenty-one he was still earning only 8s a week, and was now the eldest of ten children in the family, all still at home. ‘Our food was of the plainest, the quantity seldom sufficient. I seldom satisfied my appetite unless I called at Aunt Nancy’s after dinner to pick up what she had to spare. As to the luxury of pocket money, it was unknown.’ To pay his 1 ½d a week subscription to the Mechanics‘ Institute library, Thomas collected and sold bundles of firewood, mushrooms, and fruit in season.

In due course I was 21.1 was called upon by the master of the shop to provide a supper for the men to celebrate the occasion. In consideration of my poverty they agreed to have the supper in the shop instead of a public house. The master … cooked it in his house hard by. It was a quiet, economical affair, but I had to borrow the money to defray the expense. Trade was bad in the extreme [1843].

Thomas stayed with his master for two more years at a wage rising to £1 a week; then he moved to a bigger engineering works at Oldham, where a wage of 28s a week seemed a fortune. Here, at Platts Bros, he had the experience of working with the new Whitworth machines, but found his workmates

wicked and reckless. Most of them gambled freely on horse or dog races…. Flesh meat, as they called it, must be on the table twice or thrice a day. A rough and rude plenty alone satisfied them, the least pinching, such as I had seen scores of times without murmur, and they were loud in their complainings about ‘clamming’.

After fourteen months here Thomas was dismissed along with fifty others. He walked to Huddersfield in search of work, then to Leeds, and eventually found employment in a small engine shop at Stockton at 23s a week. Here he boarded with a butcher and grocer, where ‘there was an abundance to eat. Though potatoes were 2s a stone we had them twice a day. I often wished father and mother could have my supper instead of me.’ The last entry in the autobiography, written in 1846, records a visit to his parents, now ill and in debt:

I found father and mother suffering great want from the scarcity of work and the high price of the absolute necessities of life. [Potatoes] … were 2s per stone. Flour was usually 4s 6d and upwards…. Father would have died and seen his children die before he would have paraded his wants, or, I believe, asked for help.

Here the account ends, though we know that Thomas later became a textile engineer and, when his health failed, a school attendance officer at Keighley. He died in 1881.

Wood’s autobiography makes it clear that life in the early 1840s was, even for the skilled engineer, uncertain, and for the practitioners of a dying craft like handloom-weaving, precarious in the extreme. But with the passing of this decade, a spirit of buoyancy and optimism is almost immediately discernible, of which the Great Exhibition was at once the evidence and the symbol. In 1851 W.R. Greg pointed, from his own great experience of working-class life, to the advances which the masses had made in recent years, stressing particularly the benefits which had derived from the reduced taxes on food.6 Between 1830 and 1851 the duties on imported wheat and meat were abolished, those on sugar, coffee and tea substantially reduced:

In fact, with the single exception of soap, no tax is now levied on any one of the necessities of life; and if a working man chooses to confine himself to these, he may escape taxation altogether. Whatever he contributes to the revenue is a purely voluntary contribution. If he confines himself to a strictly wholesome and nutritious diet, and to an ample supply of neat and comfortable clothing — if he is content, as so many of the best, and wisest, and strongest, and longest-lived men have been before him, to live on bread and meat and milk and butter, and to drink only water; to forego the pleasant luxuries of sugar, coffee, and tea, and to eschew the noxious ones of wine, beer, spirits, and tobacco — he may pass through life without ever paying one shilling of taxation, except for the soap he requires for washing — an exception which is not likely to remain long upon the statute-book. Of what other country in the world can the same be said?

The fact that the working classes annually spent £53,000,000 on beer, spirits, and tobacco — a sum greater than the total annual revenue of the kingdom — was, Greg believed, sufficient evidence of their material advance.

Again, biographical records can help to illuminate the story. In 1947 a labourer who was feeding the furnace of the Clitheroe destructor picked off a heap of rubbish a manuscript cash book which proved to be the diary of John Ward, a weaver at Low Moor Mill, Clitheroe. It covers the years 1860–4, describing in some detail the everyday things of life as well as Ward’s important part in the local trade union movement and the effects of the Cotton Famine on the Lancashire cotton trade.7 Before that calamity overtook the industry, Ward was living not uncomfortably, though the dearness of food was a frequent entry in the diary: ‘June 23rd, 1860. It has been fine today. I went up to Clitheroe to meet the Committee. … I then had a look through the Market, and saw new potatoes selling at 2 ½d per pound and butcher’s meat 9d and 1 Od per pound, so I got none.’ He bought when potatoes fell in July to 5 lb for sixpence. On Christmas morning he got ‘a good breakfast of currant loaf, tea and whiskey’, possibly traditional fare for he had the same again a year later, but there is no mention of anything special for dinner. Another memorable breakfast was on Easter Sunday: ‘I got a good Cumberland breakfast of ham and eggs, which I cannot afford to get above once in a year.’ All this seems spartan enough, but the important thing is that Ward thought — and thought correctly — that he was better off than he had been earlier in life. Reviewing the past year, on New Year’s Eve 1860, he wrote:

As this year has closed I can say that I am no worse off than at the beginning. If I am anything changed it is for the better. I have better clothes, better furniture, and better bedding, and my daughter has more clothes now than ever she had in her life; and as long as we have good health and plenty of work we will do well enough.

Here was the rub. Shortly after this John Ward, like thousands of others in the cotton industry, had to endure three years of half-time work or no work at all when the American Civil War interrupted cotton imports to Lancashire. But, in general, the second half of the century saw industrial employment becoming more plentiful, more regular, and more remunerative, with wages advancing more rapidly than prices and, consequently, marked increases in the standard of comfort of the worker. More specifically, the third whom Laing had categorized in 1844 as ‘earning high wages, amply sufficient to support them in respectability and comfort’ grew in size as the century progressed, while the third ‘hovering on the verge of actual starvation’ tended to diminish.

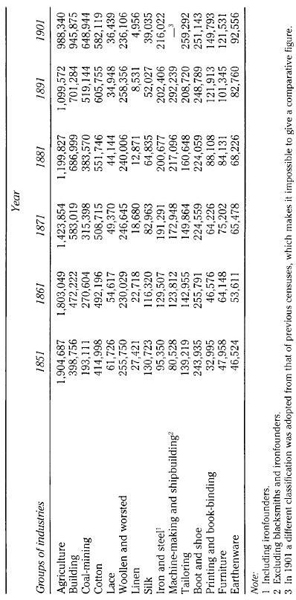

Industrialization ultimately demanded more skilled workers, less manual and unskilled labour, and though it killed old crafts like handloom-weaving, framework-knitting and lacemaking — painfully enough in many cases — it created new ones like that of the engineer, the coal-miner, and the foundry man as well as a host of ancillary industrial and commercial occupations. A comparison of the occupations of the people in 1851 and 1901 shows by how much the poorly paid employments like agriculture, linen, lace, and silk had contracted, and the relatively well-paid ones like iron and steel, machine-making and ship-building had increased during the half-century of continued industrial-ization (Table 19).

The diet of urban workers in the latter half of the century had certain well-defined characteristics which distinguished it from that of country workers. Earlier in the century there had been less difference between the two, but as urban life developed into a distinctive environment it produced marked effects on the food habits of the town-dweller. This was already apparent in the early 1860s when Dr Edward Smith carried out his pioneer investigations into diet on behalf of the Privy Council. The working class in towns could, he believed, be divided into four groups for dietary purposes: infants, young children, the wife, and the husband,8 the diet of the first being particularly bad.

Many mothers are ignorant of the fact that milk is still as necessary for the nutrition of the child after it is weaned as it was before, and they feed it with whatever food they or the older children take. Others, however desirous they may be, are unable to obtain milk; and others still, being obliged to work away from home, leave the babe to the care of a young child or to the want of care of a neighbour; or if she be always or generally away from home, pays a fixed sum for the maintenance and care of the child to someone who has an interest in feeding it on the least expensive food. Hence, speaking generally, the infant is fed both before and after it is weaned upon a sop made with crumbs of bread, warm water and sugar, and in some cases a little milk is added. Bits of bread and butter, or of meat, or any other kind of food which the mother may have in her hand are added, and not infrequently drops of gin or Godfrey’s Cordial, or some other narcotic are administered to allay the fretfulness which the want of proper food causes.

The horrors of infant feeding and ‘baby-farming’ in Victorian times have been documented by Dr Margaret Hewitt.9 The ignorance of even the most elementary principles of diet and hygiene which she discloses is appalling, but it has to be remembered that the ‘germ theory’ of infection was still new knowledge in the 1870s, and that the first patent baby food was only introduced by Liebig in 1867. Although by 1914 many of the present-day foods had appeared on the market — Allenbury’s, Nestle’s, Benger’s and so on — they were still scarcely available to the working classes on grounds of cost. Nor was fresh milk always obtainable in the towns, especially during the earlier part of the period. Smith believed that the ‘proper quantity’ of milk for infants was two to three pints per day: in his surveys he found that the average amount consumed per person was less than one pint a week. Turning to young children, he found that:

In very poor families the children are fed at breakfast and supper chiefly upon bread, bread and treacle, or bread and butter, with so-called tea; whilst at dinner they have the same food, or boiled potato or cabbage smeared over with a little fat from the bacon with which it was boiled, or in which it was fried, or have a little bacon fat or other dripping spread upon the bread, and drink water or join the mother at her tea. On Sundays they usually have a better dinner, and on week days, when a hot supper is provided instead of the dinner, they join in eating it.

The amount of milk, meat, and vegetables was, Smith noted, particularly deficient for growing children. But probably it was the wife who fared worst of all:

On Sundays she generally obtains a moderately good dinner, but on other days the food consists mainly of bread with a little butter or dripping, a plain pudding, and vegetables for dinner or supper, and weak tea. She may obtain a little bacon at dinner once, twice, or thrice a week; but more commonly she does not obtain it.

When meat or fish was obtained, it was often in the form of sheep’s trotters, sausages, black puddings, herrings, fried fish, ‘or similar savoury but not very nutritious food’. The husband was by far the best-fed member of the family, receiving the lion’s share of whatever meat was available and having at least one hot meal a day — dinner or supper depending on whether he could get home at midday-with potatoes and other vegetables. Tea was not yet generally drunk by men, who preferred beer or coffee.

The disadvantages of town life from a dietary point of view were considerable. From contemporary accounts it seems that the poorer classes were generally very ill-supplied with cooking equipment, with the result that their methods of preparing food were limited. Coupled with this was, in most parts of the country at least, the dearness of fuel, which could mean that only two or three hot meals were prepared in a week. The domestic gas oven dates from about 1855, when Smith and Phillips offered one to the public at the price of £25, and it was not until the 1890s that much cheaper forms came into common use. Before that housewives roasted the joint before an open fire or baked in a brick oven in the scullery or outhouse. The alternative method of cooking, developed from the 1820s onwards, was the iron range, of which two main versions existed — the cottage or ‘Yorkshire’ range, with an openable, barred firebox, an oven to one side and a hot water boiler on the other; and the much larger and more elaborate closed ‘kitchener’ with a series of ovens, boilers, and hot-plates, and designed for use in middle-class houses.10 Even small ranges cost from £7 upwards, and since they had to be built in and properly flued, they were regarded as landlords‘ fixtures: their progress in working-class homes was slow, and versions of these were still being installed in council houses in the 1920s. For convenience, especially in the summer months when space heating was not needed, the clear advantage lay with the gas cooker. Improvements were made in the 1860s and 1870s with the introduction of bunsen-type burners and independent gas rings, but their availability to the working classes dated from the 1890s when the renting of stoves from gas companies and payment by penny-in-the-slot meters were developed.11 London led the way in this, with 77 per cent of those served by the Gas, Light, and Coke Company having a cooker by 1914; progress was much slower in those northern towns where coal could be had cheaply.12

Other difficulties which the housewife had to face were the small outlay which she could make for food at any given time, the absence of an adequate water supply, and the fact that she had little time or opportunity to cultivate culinary skills when, as was often the case, she had to contribute to family earnings by paid employment inside or outside the home.

To accuse the urban housewife in such conditions of extravagance and bad management — as so many would-be philanthropists did — was to misunderstand her problems. That she was all too often ignorant of domestic affairs was unfortunately true, for she had never had the opportunity to learn: those who had had the experience of domestic service in middle-class households soon discovered that the methods practised there were inappropriate for their own slender means, nor were cookery lessons at the parsonage of much value for the same reasons. Formal instruction in domestic economy for girls in board schools was introduced by the new Education Code of 1876, but, not untypically, no financial provision for practical training in any branch of the subject was made, and an inspector subsequently reported that ‘the girls stumble through a mixture of learned nonsense concerning carbonaceous and nitrogenous products, but they cannot tell you how to boil a potato or cook a roast of meat‘. The same criticism applies to the cookery classes introduced in the 1890s by the technical education committees, where the accent was placed on elaborate dishes suitable for an upper-class cuisine. Dr Hewitt remarks justly, ‘Nothing perhaps so clearly indicates the profound ignorance of the middle-and upper-class Victorian of the domestic needs and conditions of the working classes than the unreality with which they attempted to improve the level of housewifery of their social inferiors.’13

In the meantime the woman who wished to improve her domestic skill was left to battle with a variety of recipe books ostensibly written for the enlightenment of the ignorant poor. The authors of these works included such gastronomic giants as Soyer (A Shilling Cookery for the People, 1855) and Francatelli (A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes, published in 1852 at 6d), as well as dieticians like Dr Edward Smith (Practical Dietary, 1864) and Sir Henry Thompson (Food and Feeding, 1884). All contained numerous well-intentioned recipes for cheap and economical dishes ranging from stirabout and oatmeal broth to risotto and pilaff. Smith worked out detailed specimen menus, costed on the basis of 1 ½d for breakfast, 2d for dinner, and 1d for supper each day, to provide the necessary minimum amount of carbon and nitrogen: his meals included a great deal of porridge, suet pudding, and skimmed milk, the meat being restricted to a little bacon and an occasional liver pudding or faggot.14 Most of the writers advocated some particular food or dish which they thought to be specially commendable to the poor on grounds of economy — in Smith’s case this was American bacon and in Thompson’s the more sophisticated haricot bean, pot-au-feu, and bouillabaisse. There is little evidence that the English working man was dissuaded of his antipathy towards soups and ‘messes’ by such recipes. In any case, what were cheap peasant dishes in the south of France or Turkey were not necessarily so in Manchester or Birmingham, where to obtain three or four pounds of fish (whiting, sole, haddock, red mullet, and conger eel), onions, carrots, tomatoes, bay leaves, garlic, cloves, thyme, parsley, capsicums, pimento, and slices of orange and lemon would have exhausted the patience as well as the budget of most busy housewives.15 Probably her husband would not have eaten it anyway. The advice to the poor of Charles Elme Francatelli, former maitre d’hotel and chief chef to Queen Victoria, was equally inappropriate: ‘To those of my readers who, from sickness or other hindrance, have not money in store I would, say, strive to lay by a little of your weekly wages … that your families may be well fed and your homes made comfortable.’16

Against these obvious difficulties of urban diet can be set a few advantages. Compared with the country village, the town had far more shops, and hence a wider choice of food. Moreover, because of keen competition between grocers and bakers, town food prices were almost always lower than those of the village shop which could exact monopoly prices. The greater specialization possible in towns also produced such useful institutions as the tripe shop and the pork butcher where, besides bacon, ham, pies, and sausages, there could be had such regional delicacies as faggots, black puddings, brawn, and haslet. The fish-and-chip shop has previously been discussed. It is possibly true, as H.D. Renner claims, that English towns were not so well served with food shops as Paris or Vienna, where one block of flats contained enough inhabitants to give butchers, grocers, greengrocers, and bakers a livelihood. The practice therefore developed in some continental cities of using the ground floor for shops, and the cellars for such purposes as baking and storing meat. The fact that food — and bread in particular — could always be obtained fresh obviated the necessity in England of having regard to its keeping quality. Toast, Renner believes, was essentially an English invention for masking staleness.17 Even so, shopping for essentials in the English industrial town rarely involved walking much further than the shop on the corner, and this easy access often meant that food was bought in dribs and drabs daily, even meal by meal. Even at the end of the century, the poor still bought tea by the half-or quarter-ounce, a farthing’s worth of milk and a pennyworth of bits of meat. John A. Hobson wrote, in Problems of Poverty:

A single family has been known to make seventy-two distinct purchases of tea within seven weeks, and the average purchases of a number of poor families for the same period amount to twenty-seven. Their groceries are bought largely by the ounce, their meat or fish by the halfpennyworth, their coal by the hundredweight or even by the pound.18

In addition to the shops, the food requirements of the large industrial towns were in part supplied by street-traders, who purveyed an astonishing volume and variety of comestibles. As described by Henry Mayhew in London, these street-sellers were by no means restricted to the coster-mongers dealing in fruit and vegetables, but included soup and eel traders (500), whelk-sellers (300), tea and coffee stall-keepers (300), sellers of sheep’s trotters (300), muffins (500), ginger-beer (1,500), besides smaller numbers dealing in pies, hot potatoes, ham sandwiches, and confectionery.19 Many of these street-trades were quite new, or had grown greatly in recent years — the ice-cream trade had only started in 1850 and patrons were still very uncertain how they should eat this novelty, while fried fish (no chips yet) was also a recent introduction. A piece of plaice or sole, battered and fried in oil, was sold with a slice of bread for 1d; oysters, at four for 1d, were already becoming something of a delicacy and not eaten by the poorest classes, though Mayhew estimated that 124 million were sold in the London streets annually. Probably the chief patrons of the stall-keepers were children and young people, street-walkers, and out-door workers such as porters and coal-heavers, but the availability of these cheap, savoury dishes was a not unimportant addition to the monotonous diet of ordinary working people in London and the larger provincial cities.

‘Eating-out’ was still highly unusual in working-class circles in this period, though here, too, provision at a modest price was growing. Single young men living away from home might eat at a pie or cook-shop, or take an ‘ordinary’ at a chop house or public house, where a slice of meat with vegetables, accompanied by cheese and beer, could be had for a few pence. When an evening meal was taken out it was usually among a party of male friends, and probably the dinner given by Mr Guppy at the Slop Barn was not untypical — veal and ham, and french beans, summer cabbage, pots of half-and-half, marrow pudding, ‘three Cheshires’, and ‘three small rums’.20 The culinary skill of the average landlord was not very high, but the stew prepared for the showmen at the Jolly Sandboys in The Old Curiosity Shop is still appetizing:

‘It’s a stew of tripe,’ said the landlord, smacking his lips, ‘and cowheel,’ smacking them again, ‘and bacon,’ smacking them once more, ‘and steak,’ smacking them for the fourth time, ‘and beans, cauliflowers, new potatoes and sparrowgrass, all working up together in one delicious gravy.’

‘At what time will it be ready?’ asked Mr Codlin faintly.

‘It’ll be done to a turn,’ said the landlord, looking up at the clock, ‘at twenty-two minutes before eleven.’

‘Then,’ said Mr Codlin, ‘fetch me a pint of warm ale, and don’t let nobody bring into the room even so much as a biscuit till the time arrives.’

On the rare occasions when a family ate out it was usually as part of a jaunt to one of the pleasure gardens, of which there were a dozen or more in London and the suburbs. By mid-century Vauxhall, Cremorne, and the rest had sunk far in the social scale, and now provided refreshment and entertainment at low cost. The working man who could not get home for dinner usually took cold food with him to eat at midday — bread with cheese, meat or dripping, and pie and potatoes were the most common — since the industrial canteen provided by the firm was still in its infancy at the end of the century. Perhaps the earliest pioneer in this direction was Sir Titus Salt who, at his model industrial village, Saltaire, provided a dining-hall where meals could be had at cost and where food brought in by the operatives of his woollen mills was cooked for them, though the printing firm Hazell, Watson, and Viney also provided a refreshment room for employees as early as 1878.21 Other pioneers of the works canteen included Colman’s, Cadbury’s, Fry’s, and Lever Bros. When J.E. Meakin compiled his account of industrial welfare schemes in 1905 he found that Cadbury’s had the largest catering facilities of any firm in Britain: dining accommodation at Bournville was provided for 2,000 employees, who could buy a roast and two vegetables for 4d, pork pie l ½d, soup and bread 1d, eggs, sausages, bacon, and pudding 1d, tea, coffee, cocoa, milk, potatoes, bread, butter, cheese and cake at ½d.22 More commonly, the larger firms by 1914 were providing merely a dining-room and facilities for food brought in by the worker to be warmed. Not all shared the sensitivity of the North-Eastern Railways Co. who, at their Gateshead works, had long deal dining-tables, each with a division ten inches high running down the middle ‘so that without rising or leaning over, no one can see what his vis-a-vis has brought, and all can go home with the comforting hallucination that their neighbours supposed them to fare better than they did’.

Turning to the actual budgets of town workers, it is immediately clear that until the 1870s little change had taken place from the earlier part of the century. The strikingly wide differences in the standard of comfort were determined by the occupation of the husband, the number of dependent children and, less important, the part of the country in which the family lived — in London rents were substantially higher than elsewhere and a garden rare, whereas in some northern industrial towns a free house and fuel went with the job. Looking first at some budgets of comfortably-off workers in mid-century, we may take a Northumberland miner with three sons all working. The family’s earnings per fortnight were:

| £ | s | d | ||

| Father, two weeks | 2 | 4 | 0 | |

| Putter, one boy, 17 years | 1 | 16 | 8 | |

| Driver, one boy, 12 years | 13 | 9 | ||

| Trapper, one boy, 8 years | 9 | 2 | ||

| £5 | 3s | 7d |

Outlay per fortnight

| Shoes, 9s per month | 4 | 6 | ||

| Clothes, stockings, etc. | 17 | 6 | ||

| Sundries | 2 | 6 | ||

| Total expenditure | £4 | 5s | 0 ¼d |

The husband contributed 1s 3d per month to a benefit club; he had rent and fuel free.23 With their 14 lb of meat each week this was an exceptionally fortunate family taken at the peak of its earning power: they could not have lived so well when the children were too young to work, nor would they do so when the sons married and left home. This budget compares with those of skilled workers collected by Le Play in 1855. A London cutler with four children occupied a house in Whitefriars Street, described as ‘less insanitary than most, but damp and sunless’. It had water laid on in the cellar, and ‘latrines’. His weekly expenditure was:24

| £ | s | d | ||

| Rent | 7 | 9 | ||

| Food | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Coal and light | 2 | 10 | ||

| Cleaning | 1 | 0 | ||

| School | 10 | |||

| Clothes | 3 | 2 | ||

| Sundries | 1 | 2 | ||

| £1 | 16s | 9d |

But another working cutler in Sheffield is apparently better off. Though his wage is only 28s a week, he puts 1s a week in the church offertory, and has saved £46 through a building society. He has only one child and much lower rent. A foundryman in Derbyshire, with four children and a wage of 27s 8d, also lives fairly well. Spending 14s a week on food, the family typically had:

Breakfast at 7. Parents — tea or coffee, with milk and sugar. Bread and butter and cold meat.Children — bread and milk.

Dinner at noon. Meat, bread, potatoes, vegetables: fruit or cheese.

Tea at 4. Tea, sugar, bread and butter.

Supper at 8. Remains of dinner.

This man had a garden, as well as the advantage of lower northern prices.

At the other extreme lay the diets of what Dr Edward Smith describes as the ‘lower fed operatives’ in his Report to the Privy Council of 1863.25 He selected for his investigation certain groups of indoor workers — silk-weavers and throwsters, needlewomen, kid-glove stitchers, stocking-and glove-weavers and shoemakers — whose earnings were known to be either low or uncertain (in fact they averaged 1 1s 9d per family per week), and by careful inquiry determined the average quantity of food which they received each week per person and per family. This was then set against his calculation of minimum subsistence. Smith found, not surprisingly, that the worst-fed class was needlewomen, of whom he investigated thirty-one London families. An adult worker ate on average each week:

| Bread | 7 ¾ 1b |

| Potatoes | 2 ½ 1b |

| Sugars | 7 ¼ oz |

| Fats | 4 ½ oz |

| Meat | 16 ¼ oz |

| Milk | 7 oz |

| Tea | 2 oz per family |

The total cost of this was 2s 7d per adult weekly. ‘They are exceedingly ill-fed, and show a feeble state of health … the amount of money spent on food is very ill-spent.’ Half the families never received any butcher’s meat, and those who did made their Sunday’s dinner from 1 d of sheep’s brains or 1 d of black pudding. At much the same level were the kid-glove stitchers of Yeovil. They received weekly:

| Bread | 8 ¾ 1b |

| Potatoes | 5 ¼ 1b |

| Sugars | 4 ¼ oz |

| Fats | 7 oz |

| Meat | 18 ¼ oz |

| Milk | 18 ¼ oz |

| Tea | 1 ¾ oz per family |

The larger quantity of milk and potatoes available in an agricultural district was the advantage here, but with a weekly expenditure on food of only 2s 9 ½d this class too was ‘ill-fed and unhealthy’. Another group of workers whose trade was now badly depressed were the Derbyshire stocking-and glove-weavers: their wages ranged from 6s to 15s a week, and for a dozen pairs of gloves they received 1s 3d, half of which was taken for stitching and frame-rent. Spending 2s 6 ¼d a week, they received:

| Bread | 11.91b |

| Potatoes | 4 lb |

| Sugars | 11 oz |

| Fats | 3 ½ oz |

| Meat | ¾ 1b |

| Milk | 1 ¼ pints |

| Tea | 2 oz per family |

| Cheese | ¾ lb per familyy |

A typical diet of this group was:

No. 92, Horsley Woodhouse.

Breakfast. Milk and oatmeal for the children: coffee, bread, and sometimes bacon for the adults.

Dinner. Always hot, and with meat or bacon and vegetables or bread daily.

Tea. Tea, bread and butter or treacle.

Supper. Milk.

These workers, reported Smith, were ‘moderately fed, but do not exhibit a high state of health’. The trade of the silk-weavers had also been depressed in recent years, though it was still carried on widely in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green, as well as in Coventry and Macclesfield. The class was ‘insufficiently nourished, and of feeble health’, as a specimen diet indicates:

No. 38, Coventry.

Breakfast. Children have bread and treacle, adults have tea or coffee and bread with lettuce perhaps.

Dinner. Bacon and potatoes, and in this case the bacon and potatoes are boiled together, and the water is thrown away!

Tea. Tea and bread.

Supper. Bread and cheese.

The best-paid group were the shoemakers of Northampton and Stafford, who could earn from 12s to £2 a week, according to skill. Their diet, however, was little better than that of the others, since, said Smith, ‘shoemakers are not a thrifty and well-conducted class’. Adult workers ate:

| Bread | 11.21b |

| Potatoes | 3 ½ lb |

| Sugars | 10 oz |

| Fats | 5 ¾ oz |

| Meat | 15 ¾ oz |

| Milk | 18 oz |

| Tea | 3 ¼ oz per family |

| Cheese | 14 oz per familyy |

A Stafford family’s daily fare was as follows:

Breakfast. Tea, bread and butter, with milk added to the tea for the children.

Dinner. Meat, Sunday and Monday, with vegetables, and other days bacon and bread.

Tea. Same as breakfast.

Supper. Bread, cheese and beer for the parents, milk and bread for the children.

Putting all his results together, Smith discovered that these indoor workers were considerably worse fed than agricultural labourers, and were, indeed, below his estimate of minimum subsistence with respect to the nitrogen content of the diet:

| Carbonaceous foods | Nitrogenous foods | |

| Minimum subsistence | 28,600 grains | 1,330 grains |

| English farm labourers | 40,673 grains | 1,594 grains |

| Indoor workers | 28,876 grains | 1,192 grains |

For the first time, a quantitative calculation based on the best available scientific evidence had revealed the existence of what, in later years, became known as ‘the submerged tenth’ — a substantial proportion of the industrial community which could not maintain itself in a state of bare physical efficiency. Put into modern nutritional terms, the average diets of these indoor workers provided 2,190 kilocalories a day, 55 g of protein, 53 g of fat, 12.5 mg of iron, and 0.36 g of calcium; the poorest group, the needlewomen, received only 1,950 kilocalories and 49 g of protein. If, as Dr Smith was convinced, the adult male workers in the other occupations took the lion’s share of the food, especially of the meat, bacon, and cheese, it follows that wives and children received less than the averages quoted here, and relied mainly on bread and potatoes smeared with dripping or treacle. Almost certainly their calorie intake would be low enough to affect the growth of children, and the protein intake inadequate for pregnant and lactating women as well as for children. The calcium intake was extremely low by modern standards but, unfortunately, the data do not exist for an estimate of vitamins.26 These workers were considerably worse fed than the agricultural labourers examined by Smith, whose diets work out to 2,760 kilocalories, and 70 g of protein: the indoor workers consumed more sugar than the labourers, but less bread and meat, and much less milk and potatoes.

Such was the dietary condition of some of the poorest-paid, fully employed workers in the ‘Golden Age’ of Victorian prosperity. But the better-off sections above them could quite easily be pulled down to the same or to an even lower level by unavoidable misfortune — the death of the chief wage-earner, accident, sickness, old age, or infirmity. A dramatic example of the precariousness of life for reasonably well-paid workers is given by the Cotton Famine when, during the American Civil War of 1861–5, the northern states blockaded the southern ports and practically stopped the export of raw cotton to Lancashire, so depriving thousands of spinners and weavers of their livelihood. John Ward’s Diary describes how the event affected the life of a Clitheroe weaver who had been used to living proudly and comfortably:

31st August 1861, this has been a fine day. We got notice at our mill this morning to run four days per week until further notice.

November 16th … I read the newspaper, but there is nothing fresh from America nor any word from the naval expedition that has gone to the south. There is great distress all through the manufacturing districts: they are all running short time through the scarcity of cotton.

April 1 Oth, 1864. It is nearly two years since I wrote anything in the way of a diary. I now take up my pen to resume the task. It has been a very poor time for us all the time owing to the American war, which seems as far off being settled as ever. The mill I work in was stopped all winter, during which time I had three shillings per week allowed by the Relief Committee, which barely kept me alive. When we started work again it was with Surat cotton, and a great number of weavers can only mind two looms. We can earn very little. I have not earned a shilling a day this last month. … My clothes and bedding is wearing out very fast, and I have no means of getting any more…. The principal reason why I did not take any notes these last two years is because I was sad and weary. One half of the time I was out of work, and the other I had to work as hard as ever I wrought in my life, and can hardly keep myself living. If things do not mend this summer I will try somewhere else or something else, for I can’t go much further with what I am at….27

The plight of the Lancashire operatives naturally aroused public sympathy and concern, and voluntary relief committees at least kept most of the unemployed out of the workhouse. At the end of 1862 272,000 people were receiving out-relief from the boards of guardians, and almost as many again were being supported by charitable organizations.28 Such was the national concern for these unfortunate victims of unemployment, to whom the usual Victorian explanation of moral failing could not be attached, that Dr Edward Smith was again commissioned to survey their diet, and to compare their present condition with that before the depression. He found that the average income of the families had fallen from a comfortable 39s 6d a week in 1861 to 14s in 1862, and the amounts spent per head on food from 3s 3d to 1s 1 1d. The consumption of meat and potatoes had fallen by 70 per cent, of fats by 50 per cent, and of bread by 35 per cent; sugar had only fallen by 25 per cent, and was partly replaced by treacle, while milk consumption had remained stable at 1.4 pints per person per week. In total, the intake of calories had fallen from 3,370 kilocalories a day to 2,220, and protein from 84 to 56 g a day (both still a little higher than the normal diets of the indoor workers previously discussed). The interesting observation here is that in a period of greatly reduced income, the cotton workers had not given up the more expensive or ‘unnecessary’ foods like meat and sugar in favour of cheap, filling sources of energy such as bread and potatoes, but had chosen to reduce their consumption of nearly all foods, though by different amounts. It illustrates the conservatism of food habits, and the desire to preserve a palatable diet albeit at the expense of quantity.29

Few of the budgets of the period mention expenditure on drink — probably because of a natural reluctance to admit to something which in the new climate of Victorian morality and temperance was regarded as one of the great national evils — although we know that the per capita consumption of beer was rising to its peak of 34 gallons per year in 1876. Thereafter, it remained at around 30 gallons until 1900, from which time it began a slow fall. Certainly, many families in the later nineteenth century lived in self-inflicted poverty because of what they spent at the public house. By 1850 beer had already lost whatever claim it had once had to be called the national drink: it was mainly a man’s drink, women preferring tea, or spirits, or both. William Hoyle calculated that the expenditure per head of the population on drink was £2 18s lOd in 1850, rising to £4 7s 3d in 1875,30 while Samuel Smiles estimated that in the later year the working classes spent £60,000,000 on drink and tobacco.31 It seems likely, then, that the average working-class household was devoting between £15 and £20 a year to alcohol; and when allowance is made for the growing number of teetotallers, it means that some families must have spent a third, and possibly even half, of all their income on drink.32 Hoyle wrote:

We are acknowledged to be by far the richest nation in the world, and yet a great portion of our population are in rags. Why is this? 1s it because they get insufficient wages that they are poor? No! For wages are relatively higher in England than almost in any country in the world; but it is because they squander their earnings improvidently upon things that are not only needless, but useless and hurtful.

By the end of the century temperance and Band of Hope movements were having some success, and the growth of new leisure pursuits was beginning to provide attractive alternatives to the public house, but on the eve of the First World War the national drink bill was still £164,000,000, or £3 10s lOd for every man, woman, and child in the country.33 Rowntree and Sherwell calculated in 1900 that every male drinker consumed on average 73 gallons of beer a year and 2.4 gallons of spirits,34 while in that year 182,000 people in England and Wales were convicted of drunkenness, almost a quarter of them women.35 In London, one house in every seventy-seven was a public house36 and The New Survey of London Life and Labour, which launched a searching inquiry into the matter, concluded that as much as one-quarter of the average poor family’s income was still spent by the husband and wife on drink.37 The interesting fact was, however, that heavy drinking had now sunk to the bottom of the social scale: the proportion fell off progressively as incomes rose, so that ‘of all working-class family incomes, other than the poorest, from 10 per cent in the better-off to 15 per cent in the less prosperous, was spent on drink’. By 1914 the great brewery companies, who controlled a majority of the public house outlets for their beers, were seriously concerned about declining consumption and increasingly restrictive licensing policies. Much money had been spent in the 1880s and 1890s on rebuilding and refurbishing public houses to produce a ‘glamorous and theatrical’ effect,38 but they faced growing competition from the Coffee House Companies, which offered food and entertainment as well as non-alcoholic drinks, and from the People’s Refreshment House Association, founded in 1896, which was taking over public houses in small towns and country districts, and also providing refreshments and recreational facilities as rival attractions to the demon drink. These developments were giving rise to a Public House Reform Movement — an attempt to give licensed premises greater respectability by, on the one hand, providing comfort and amenities as well as liquor, and, on the other, by enforcing stricter order and managerial control.

During the last quarter of the century — the period which economic historians have designated the ‘Great Depression’ — improvements are observable in the general standard of working-class diet. More than anything else, these were due to the falling prices of basic foodstuffs like wheat and meat (seeChapter 6, pp. Ill ff.). Robert Giffen calculated in 1879 that there had already been a fall of 24 per cent in prices since the onset of the depression in 1873,39 nor had the trough yet been reached; as it neared its end in 1895, A.L. Bowley made a pioneer study for the Statistical Society of the changes which had taken place in real wages (i.e. the purchasing power of earnings), and concluded that between 1860 and 1891 they had risen by no less than 92 per cent:40

In so far as actual want is now only the lot of a small proportion of the nation (though intrinsically a large number) and comfort is within the reach of increasing masses of workmen, the greatest benefit of this prosperity has fallen to wage earners; but this is only the righting of injustice and hardship. In 1860 it was the working classes who were in most need of any benefit that might accrue to the nation, and it would have been only reasonable to expect that their progress in actual money (apart from better conditions of work) should be at least as rapid as that of the richer classes.41

The other principal factor which was enlarging the quantity and variety of working-class consumption at this time was the series of changes taking place in the supply and distribution of foodstuffs. Of the growth in imports of wheat, meat and other foods we have already spoken. Also significant were the changes which occurred in the supply of milk.

Before the outbreak of the cattle disease (rinderpest) in 1865 by far the larger part of the towns‘ milk was obtained from town dairies. The cattle which lent themselves best to this artificial town life were imported Dutch cows, but they were found to be much more susceptible to the disease than country animals: of 9,531 cows in the Metropolitan Board of Works area, 5,357 were attacked by the plague, and of these only 375 recovered.42 The lesson so painfully learned of the unhealthiness of town-fed cows resulted in the imposition of such strict sanitary regulations on town dairies that very many closed down almost immediately, and from this time onwards the industrial town came to be supplied largely by country milk. In the case of London, this was soon being brought by rail from the west country and Derbyshire — distances up to 150 miles. Before many years, the wholesale milk trade was being concentrated into large firms who, through their contracts with farms, were able to control minutely the quality and condition of milk as well as the general sanitary condition of the farm. In the later years of the century a supply of milk purer than the townsman had ever known was becoming available, and milk consumption was slowly beginning to rise. At 2d a pint, however, it was still relatively expensive, and a survey carried out in 1902 showed that while the consumption of middle-class families was 6 pints per head a week, that in the lower middle class was 3.8 pints, among artisans 1.8 pints, and among labourers only 0.8 pints.43 The economic gradients were still very steep, especially in the choice of foods not regarded as essential. In 1889 it was officially calculated that families with incomes of less than £40 a year spent 87.42 per cent of this on food while those with £100-&110 spent only 42.49 per cent on a wider range of foods.44

In 1902 the Statistical Society carried out a survey of the household budgets of 223 of its members with a view to calculating the level of consumption of some basic foods.45 The Society’s members were not so unrepresentative as might be imagined, including landed proprietors, merchants, railway directors, civil servants, doctors, lawyers, farmers, clerks, salesmen, electricians, compositors, printers, decorators, sugar boilers, shipwrights, labourers, and farm labourers from all parts of the country. For the purposes of the inquiry they were grouped into four classes:

Group 1: Wage-earners, 82 households.

Group 2: Lower middle class, 60 households.

Group 3: Professional classes, 46 households.

Group 4: Upper classes, 32 households.

Detailed returns had to be kept for a minimum of four weeks, which, in addition to the actual quantities of food consumed, took account of the number present at each meal and meals taken away from home. The survey therefore represented the first major attempt to compare the food consumption of different classes of the community. The results are illuminating. Although we are only concerned here with Groups 1 (wage-earners) and 2 (including clerks, insurance agents, trade union secretaries, small tradesmen), the other groups are included for comparison:

| Meat (lb per head per annum) | Milk (galls per annum) | Cheese (lb per annum) | Butter (lb per annum) | |

| Group 1 | 107 | 8.5 | 10.0 | 15 |

| Group 2 | 122 | 25.0 | 10.0 | 23 |

| Group 3 | 182 | 39.0 | 8.5 | 29 |

| Group 4 | 300 | 31.0 | 10.5 | 41 |

Apart from the striking differences in levels of consumption of most foods between the different classes, the figures for Group 1 suggest a major improvement since the time of Edward Smith’s survey forty years earlier. In particular, meat consumption had more than doubled, and both butter and milk consumption had grown appreciably. The figures are, of course, not strictly comparable, since Smith was reporting on groups of poorer labouring families while the Statistical Society’s survey reflected more the consumption patterns of better-paid workers, but both were at their different times reasonably typical of the working class as a whole. The 1902 survey also contained interesting international comparisons which showed that, while Britain was the heaviest meat-eater of all European countries, she was the smallest milk-drinker.46

By the end of Victoria’s reign it seemed that large sections of the working class were making impressive strides towards comfort and prosperity. Even critics of the factory system were bound to admit that though wages still remained low they provided an infinitely higher standard than formerly: the earnings of Lancashire cotton operatives, wrote Allen Clarke in 1913, permitted ‘a breakfast of coffee or tea, bread, bacon and eggs — when eggs are cheap — a dinner of potatoes and beef, an evening meal of tea, bread and butter, cheap vegetables or fish, and a slight supper at moderate price’.47

Because of these evidences of improvement, many contemporaries had assumed that all sections of labour were on the up-grade, that poverty and destitution were vanishing phenomena — perhaps inevitable during the early days of industrialization, but bound to disappear once the system in its maturity came to distribute its blessings throughout society. This complacency was rudely shaken towards the end of the century by a series of disclosures which, by dispassionate, sociological inquiry, showed that a vast and unsuspected amount of poverty still existed in English towns and villages, and that while it was true that some branches of labour had made significant gains in recent years, other sections had remained sunk in misery so abject as to be inaudible. The ‘bitter cry of outcast London’ was, in fact, only detected by the trained ear of the social investigator.

The work of discovery began with Charles Booth’s great survey of life and labour in London, started in 1886 and completed, seventeen volumes later, in 1902. Undertaken initially in order to refute what he considered the exaggerated propaganda of the Social Democratic Federation about the extent of poverty in London, Booth discoverd that at a ‘poverty-line’ of 21s a week or less for a man, wife, and three children, 30.7 per cent of the population of London were in ‘want’ as against 69.3 per cent in comfort.48 Booth collected detailed budgets from 55 working-class families in the East End. Assuming an equal distribution of food within the family, they provided 6.5 lb of bread per person per week, 2.1 lb of potatoes, 12 oz of sugar, 1.6 lb of meat, 3.9 oz of fats, and 1.4 pints of milk: in present-day nutritional terms this gives 2,620 kilocalories a day, 61 g of protein, 57 g of fat, 10.6 mg of iron, and 0.3 g of calcium.49 These diets therefore compared closely, though rather unfavourably, with those of the indoor workers collected by Edward Smith a quarter of a century earlier.

In more polemical language William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, was at the same time writing of ‘the disinherited’ or ‘the submerged tenth’, those unfortunates who did not even qualify for the standard of comfort given to the London Cab Horse:

The denizens in Darkest England for whom I appeal are (1) those who, having no capital or income of their own, would in a month be dead from sheer starvation were they exclusively dependent upon the money earned by their own work; and (2) those who by their utmost exertions are unable to attain the regulation allowance of food which the law prescribes as indispensable even for the worst criminals in our gaols.50

Within a few years, other writers had demonstrated that the proportion of poverty ascertained by Booth was not peculiar to the metropolis, but existed in industrial towns throughout the country. In his study of York, Seebohm Rowntree concluded that 9.9 per cent of the whole population was in ‘primary’ poverty and 17.9 per cent in ‘secondary’ poverty — no less than 28 per cent who were unable to afford the 3,500 kilocalories a day necessary for a man in moderate work; incidentally, Rowntree’s minimum dietary included no fresh meat, and was therefore less generous than the workhouse regimen.51 The labourer, he found, was particularly underfed during three phases of his life — in childhood, in early middle life when he had a family of dependent children, and lastly in old age. Twenty working-class budgets collected by Rowntree were very similar to Booth’s London sample, providing an average of 2,050 kilocalories, 57 g of protein, and 59 g of fat per person per day. Rowntree also gathered some budgets from the ‘servant-keeping’ (i.e. middle-class) families of York, and a comparison of these with families earning less than 18s a week shows how wide was the dietary divide between classes. The poorest received only 1,578 kilocalories a day while the middle class had 3,526, only 42 g of protein compared with 96, and 40 g of fat against 139.52 Rowntree observed that in these poor families it was expected that the husband should be reasonably well fed, even if at the expense of the rest of the family:

We see that many a labourer, who has a wife and three or four children, is healthy and a good worker, although he earns only a pound a week. What we do not see is that in order to give him enough food, mother and children habitually go short, for the mother knows that all depends upon the wages of her husband.53

A few years later, a survey of the four towns — Northampton, Warrington, Stanley, and Reading — disclosed that 32 per cent of adult wage-earners received less than 24s a week, and that 16 per cent of the working classes were living in a condition of primary poverty. Large families were given as the chief cause of destitution, with the result that the proportion of infants and school children living below the poverty-line was alarmingly higher than the average; in Reading, for example, as many as 45 per cent of those under five, and 47 per cent of those under fourteen were in this condition.54 Even among the relatively well-paid ironworkers of Middlesbrough, 125 out of 900 working-class households investigated were found to be ‘absolutely poor’, and another 175 ‘so near the poverty-line that they are constantly passing over it’. ‘That’s is,’ wrote Lady Bell, ‘the life of a third of these workers whom we are considering is an unending struggle from day to day to keep abreast of the most ordinary, the simplest, the essential needs.’55 The verdict of these independent researches, and of three government inquiries which took place during the same period — the Report on the Aged Deserving Poor (1899), the Report on Physical Deterioration (1904), and the Reports of the Royal Commission on the Poor Law (1905–9) — were remarkably unanimous and unmistakable: below the outward prosperity and gaiety of Edwardian England, there persisted a degrading misery which blighted the lives of vast numbers of the people, which kept them, if not in actual starvation, at least in constant want, which sentenced young children to malnutrition and physical deficiency and consigned one-third of its old people to death in the workhouse.

Actual starvation was not unknown in ‘darkest England’. Some of General Booth’s shelter men saw a man stumble and faint in St James’s Park in 1890, who died shortly afterwards in hospital: he had walked from Liverpool without food for five days, and the jury at the coroner’s inquest returned a verdict of ‘death from starvation’. Thousands of unemployed and casual labourers who lived and slept in the streets of London and provincial cities existed on the brink of this condition; some were drunks, loafers, and thieves, but if the records of the Salvation Army are to be credited, a high proportion were decent men and women who desperately wanted work but could not find it. One example must stand for many:

I’m a tailor. Have slept here [the Embankment]ifour nights running. Can’t get work. Been out of a job three weeks. If I can muster cash I sleep at a lodging-house. … It was very wet last night. I left these seats and went to Covent Garden Market and kept under cover. There were about thirty of us. The police moved us on, but we went back as soon as they had gone. I’ve had a pen’orth of bread and pen’orth of soup during the last two days — often goes without altogether. There are women sleep out here. They are decent people, mostly charwomen and such who can’t get work.56

For the growing problem of unemployment public relief and private philanthropy still did little despite the devoted work of such agencies as the Salvation Army and the charity organizations. A man might find temporary shelter in a casual ward, but here he was required to break 10 cwt of stones for an inadequate diet of ‘bread and scrape’ — breakfast 6 oz of bread and 1 pint of skilly, dinner 6 oz of bread and 1 oz of cheese, tea same as breakfast.57 Below this there lay only the alternative of entering the workhouse proper, and it is significant that in 1912 the number of inmates reached an all-time peak of 280,000.

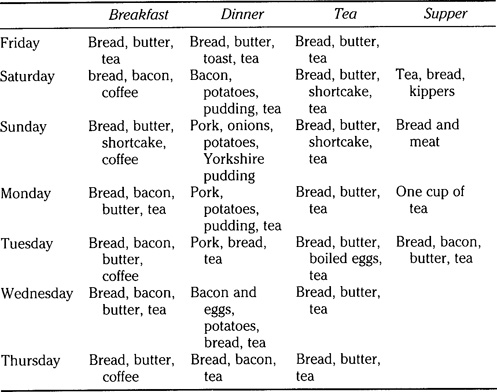

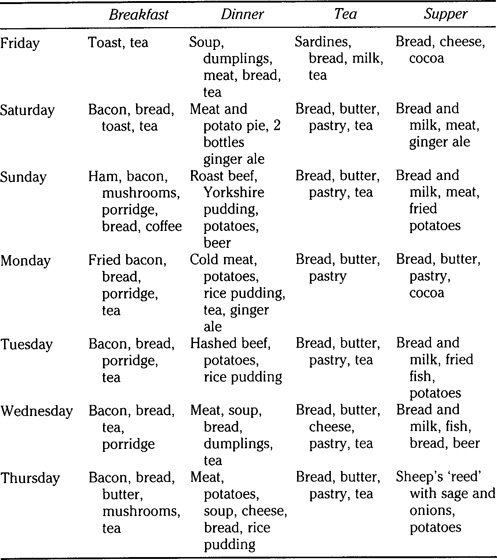

From the budgets and weekly menus collected by Rowntree in York in 1901,58 it is possible to trace with some exactness the food of the regularly employed working class at this period. No detailed budgets were in fact received from households in Class A (earnings under 18s week), where the 2s 7d per person a week available for food would secure little more than bread, potatoes, tea, and margarine. Fairly representative of Class B (earnings 18s to 21s week), though with an unusually small family of only two children, was a carter receiving 20s a week: the family’s food was starchy and monotonous, deficient in protein value by 18 per cent (Table 20).

A family in Class C (earnings 21s to 30s weekly) where the husband, a polisher, earned 25s a week, had somewhat more variety in its diet, though the additional child pulled down the total nutritional value to very

Table 20 Menu of meals provided during the week ending 22 February 1901

much the same level as the previous case: there was a deficiency of 25 per cent in protein and 7 per cent in energy value (Table 21).

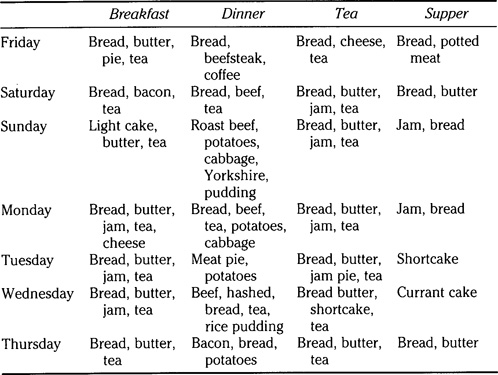

Finally may be taken an example of a reasonably good dietary received by a Class D household (skilled workers, earnings over 30s weekly) where the husband was a foreman receiving 38s a week, and a teetotaller. Only 32 per cent of the York households fell into this income category (Table 22).

One of the difficulties is to know how representative these budgets were. In most cases, the family which was living reasonably well and where the housewife was eager to show off her thrifty management was the one to keep a budget satisfactorily, whereas those families about whose expenditure one would like to have details either could not or would not collect the information. We know that in many such households drink and betting seriously reduced what might otherwise have been an adequate wage to something well below the minimum requirement. Another difficulty is to know precisely how much of a weekly wage was available for food expenditure after making the necessary deductions for rent,

Table 21 Menu of meals provided during the week ending 22 June 1901

clothes, fuel, sundry expenses, and, all too often, repayment of debts. Lady Bell in her investigations in Middlesbrough found that a man earning 18s 6d spent only 7s 5d on food after paying rent 5s 6d, coal 2s 4d, clothing 1s, tobacco 9d, cleaning materials 8d, and insurance 7d, while a man earning 30s a week could afford to devote 16s 2 ½d to food. In a careful household like the first, the wife, on receiving the weekly wage, immediately set aside money for the recurrent out-goings and spent what she had left on food: the result was that the family passed as ‘respectable’ but was frequently inadequately nourished. The first family spent 3s 1 1d less each week on food than the amount allowed for maintenance in the York workhouse.59

In 1903, the Board of Trade published the results of 286 urban workmen’s budgets, the average earnings of whom were 29s lOd a week. These showed that the expenditure on meat was now much heavier than that on bread — 6s 3 ¾d compared with 3s 6 ½d — the other items being, in order, butter (1s 8 ½d), milk (1s 5d), potatoes (1s 2d), other vegetables and fruit (1s O ½d), tea (11 ¾d), eggs (11 ½d), and sugar (10d).60

The change in the pattern of expenditure since Dr Smith’s inquiry forty years earlier is noticeable and important, indicating a marked growth in protein as against carbohydrate foods, although fruit, green vegetables,

Table 22 Menu of meals provided during the week ending 30 September 1889

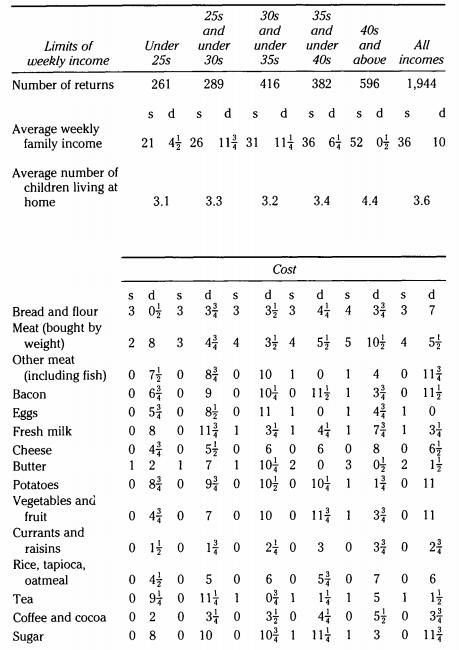

and fish were still comparatively insignificant items. In 1904 a much wider survey, embracing nearly two thousand families more representative of the whole country, gave a complete account of expenditure on food arranged under five income headings (Table 23).

Although even the poorest families (average income 21s 4 ½d) spent more on meat than on bread, and varied what was still a starchy, monotonous diet with cheese and pickles, jam and treacle, the highest-paid workers (average income 52s 0 ½d) spent three times as much on fruit

Table 23 Average weekly cost and quantity of certain articles of food consumed by workmen’s families in 190461

and vegetables, butter and eggs, and more than twice as much on milk. At a time when the term Vitamins‘ had not yet been coined, the results of their deficiency in the diets of the poor were all too apparent. What food was like at Round About a Pound a Week — the income of between a quarter and a third of all families in Edwardian England — was well described by Mrs Pember Reeves in south London and by Robert Roberts in Salford, Lancashire. In 1913 Mrs Reeves described families of wage-earners in which there was less than 2d a day each for food, where ‘the tiny amounts of tea, dripping, butter, jam, sugar and greens may be regarded rather in the light of condiments than of food’.62 Here, bread was still unquestionably the staple, especially for children:

Bread … is their chief food. It is cheap; they like it; it comes into the house ready cooked; it is always at hand, and needs no plate and spoon. Spread with a scraping of butter, jam or margarine, according to the length of purse of the mother, they never tire of it as long as they are in their ordinary state of health… .It makes the sole article in the menu for two meals a day.63

And from Salford in Lancashire comes a similar account:

A treat for the smallest child consisted of a round of bread lightly sprinkled with sugar — the ‘sugar butty’. But such was the craving for sweetness among the most deprived, some children I have known would take leaves from the bottom of their father’s pot and spread them over bread to make the ‘sweet tea-leaf sandwich’.64

National concern about the physical fitness of the population dated from at least as early as 1885, when James Cantlie published his book on Degeneracy amongst Londoners. He argued that a progressive deteriora-tion occurred among town-dwellers, so that by the third generation the average male could achieve, at maturity, only ‘height, 5 ft 1 in; chest measurement 28 in. His aspect is pale, waxy: he is very narrow between the eyes, and with a decided squint.’65 These anxieties seemed to be confirmed by the South African War () when the Inspector- General of Army Recruiting reported that 37.6 per cent of volunteers had been found unfit for service or had subsequently been invalided out. How was our industry, our navy, and, above all, our Empire to be maintained if the cities, where three-quarters of the whole population now lived, were ‘the nurseries of a degenerate race?

Whether, in fact, the nation’s health was in decline was unprovable, since no comparable data for an earlier period existed against which the findings of the Committee on Physical Deterioration could be matched, but there was abundant evidence of a generally low standard of health, particularly among the children of the working classes. In 1911, infant mortality, still high in the middle and upper classes at 77 deaths per thousand, doubled to 152 per thousand among unskilled labourers, while at age thirteen boys from this class were four inches shorter than the sons of middle-class parents.66

By the early twentieth century ‘National Efficiency’ had become a slogan which, for different reasons, almost all political parties could support. It fell to the Liberal government after 1906, spurred on by the emerging Labour party, to introduce a series of measures which have sometimes been hailed as the foundation of the Welfare State. Ever since the extensions of elementary schooling in the previous century teachers had been aware that hungry children made poor scholars and, beginning in 1864 with the Destitute Children’s Dinner Society, voluntary bodies had been providing free or ‘penny dinners’ for poor children in some cities.67 In 1906 the Education (Provision of Meals) Act widened the coverage by allowing local authorities to levy a rate of a halfpenny in the pound to provide meals for children ‘unable by reason of lack of food to take full advantage of the education provided for them’. By 1914 200,000 children out of a school population of 6,000,000 were receiving meals at the public expense. The Act was followed in 1907 by the Education (Medical Inspections) Act, providing for the medical examination of children three times during their school life, and extended in 1912 by Exchequer grants to education authorities providing medical treatment in school clinics. In 1908 non-contributory old age pensions of 5s a week were granted to poor people over the age of seventy, and three years later the National Insurance Act provided medical treatment for wage-earners (though not their dependants) through a ‘panel’ doctor scheme.

By 1914 the principles of state responsibility, particularly for the young and the old, were coming to be widely recognized, and the replacement of the old Poor Law by what the Webbs called a ‘framework of prevention’ was imminent. The unforeseen outbreak of war brought to an untimely end this first national attempt to raise the standards of those submerged millions of whom Britain became suddenly proud in the trenches of France.

Notes

1 Laing, Samuel (1844) Atlas Prize Essay: National Distress. Its Causes and Remedies, 8.

2 Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population by the Poor Law Commissioners (E. Chadwick), HL, XXVI (1842).

3 Laing, op. cit., 27.

4 See Burnett, John, Vincent, David, and Mayall, David (eds) (1984/1987) The Autobiography of the Working Class. An Annotated, Critical Bibliography, Vol. I, 1790–1900, Vol. II, 1900–1945. Each volume locates and abstracts approximately 1,000 working-class autobiographies.

5 The Autobiography of Thomas Wood, 1822–1880 (privately published, 1956).

6 A review by W.R. Greg of William Johnston’s England as it is; Political, Social and Industrial, in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century in the Edinburgh Review CXC (April 1851), 305 et seq.

7 France, R. Sharpe, TheDiaryofJohn Ward of Clitheroe, Weaver, 1860–1864. Transactions o f the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 105 (1954), 137 et seq.

8 Smith, Edward (1864) Practical Dietary for Families, Schools, and The Labouring Classes, 196 et seq.

9 Hewitt, Margaret (1958) Wives and Mothers in Victorian Industry. See particularly chap. VII, The sacrifice of infants‘, chap. IX, ’Day nursing and its results‘, and chap. X, Infants’ preservatives‘.

10 Yarwood, Doreen (1983) Five Hundred Years of Technology in the Home, 60–2.

11 Burnett, John (1986) A Social History of Housing, 1815–1985, 215.

12 Daunton, M.J. (1983) House and Home in the Victorian City. Working-Class Housing, 1850–1914, 240.

13 Hewitt, op. cit., 80.

14 Smith, op. cit., 229 et seq.

15 Thompson, Sir Henry (1884) Food and Feeding (3rd edn), 173.

16 Francatelli, Charles Elme (1852) A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes, 10–11.

17 Renner, H.D. (1944) The Origin of Food Habits, 220–2.

18 Quoted in Robert Blatchford (1908) Merrie England, 52.

19 Mayhew, Henry (1861) London Labour and the London Poor: The Condition and Earnings of those that will work, cannot work, and will not work, vol. I, London Street-Folk, 166 et seq.

20 Spencer, Edward (Nathaniel Gubbins) (1900) Cakes and Ale. A Memory of Many Meals, 255.

21 Gilman, Nicholas Paine (1899) A Dividend to Labour.

22 Meakin, J.E. Budgett (1905) Model Factories and Villages.

23 Quoted in Laing, op. cit., 39.

24 Quoted in G.M. Young (ed.) (1934) Early Victorian England. 1830–1865 I, 133.

25 Sixth Report of the Medical Officer of the Privy Council, 1863: Report by Dr Edward Smith on the Food of the Poorer Labouring Classes in England, ‘Indoor Occupations’, 219 et seq.

26 Barker, T.C., Oddy, D.J., and Yudkin, John (1970) The Dietary Surveys of Dr Edward Smith, 1862–3. A New Assessment, 39–47.

27 Ward, op. cit., 167, et seq.

28 Longmate, Norman (1978) The Hungry Mills. The Story of the Lancashire Cotton Famine, 1861–5, 151. This contains many vivid contemporary accounts of the distress.

29 Barker, Oddy, and Yudkin, op. cit., 40–1.

30 Hoyle, William (1871) Our National Resources and How They are Wasted. An omitted Chapter in Political Economy. Series extended in Hoyle and Economy (1887).

31 Smiles, Samuel (1905) Thrift, 114.

32 Leone Levi in 1885 put the average weekly income of the working-class family at 32s. The annual expenditure on drink was therefore approximately £20 per family out of an income of £80. Levi, Leone (1885) Wages and Earnings of the Working Classes, a report to Sir Arthur Bass, MP, 12.

33 Wilson, George B. (1940) Alcohol and the Nation, Appendix F, Table 31.

34 Rowntree, J. and Sherwell, A. (1900) The Temperance Problem and Social Reform.

35 Johnston, James P. (1977) A Hundred Years of Eating. Food, Drink and the Daily Diet in Britain since the late Nineteenth Century, 92.

36 Shadwell, Arthur (1902) Drink, Temperance and Legislation, 28.

37 The New Survey of London Life and Labour (1934) IX, 246 et seq.

38 Thorne, Robert (1985) The public house reform movement‘, in Derek J. Oddy and Derek S. Miller (eds) Britain, 234 et seq.

39 Giffen, Robert (1879) ‘On the fall of prices of commodities in recent years’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society XLII, 39.

40 Bowley, A.L. (1895) ‘Changes in average wages (nominal and real) in the United Kingdom between 1860 and 1891’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society LVIII, 225.

41 ibid., 251–2.

42 Bannister, Richard (1888) ‘Our milk, butter and cheese supply’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts XXXVI, 967.

43 Cohen, Ruth L. (1936) The History of Milk Prices — An analysis of the factors affecting the prices of milk and milk products, 4–5.

44 Board of Trade Labour Statistics (1889) Returns of Expenditure by Working Men, pp. LXXXIV.

45 Production and Consumption of Meat and Milk, Second Report from the Committee appointed to inquire into the statistics available as a basis for estimating the production and consumption of meat and milk in the United Kingdom, published in Journal of the Royal Statistical Society LXVIII (1904), 368 et seq.

46 ibid., 426. Meat consumption (pounds per head per annum): United Kingdom 122, Germany 99, France 80, Belgium 70, Sweden 62. Milk consumption (gallons per head per annum): Saxony 46, Sweden and Denmark 40, France 16, United Kingdom 15.

47 Clarke, Allen (1913) The Effects of the Factory System.

48 Booth, Charles (1970) Life and Labour of the People in London II (First series: Poverty), 21.

49 Oddy, D.J. (1970) ‘Working-class diets in nineteenth-century Britain’, Economic History Review (2nd series) XXIII (1, 2, and 3), 319.

50 Booth, General (1890) In Darkest England, and the Way Out, 18.

51 Rowntree, B. Seebohm (1901) Poverty. A Study of Town Life.

52 Oddy, op. cit., 319.

53 Rowntree, op. cit., 135.

54 Bowley, A.L. and Burnett-Hurst, A.R. (1915) Livelihood and Poverty. A study in the economic conditions of working-class households in Northampton, Warrington, Stanley and Reading, 43 et seq.

55 Bell, Lady (Mrs Hugh Bell) (1907) At the Works. A study of a manufacturing town, 51.

56 Gen. Booth, op. cit., 27.

57 For a first-hand account of the parsimony of organized charity, see Jack London (1902) The People of the Abyss.

58 Rowntree, op. cit., chap. VIII, ‘Family budgets’, 222 et seq.

59 Lady Bell, op. cit., 56 et seq.

60 Memoranda, Statistical Tables, and Charts prepared in the Board of Trade with reference to various matters bearing on British and Foreign Trade and Industrial Conditions, Cd. 1761 (1903), 212–14.

61 Second Series of Memoranda, Statistical Tables, and Charts prepared in the Board of Trade, etc., Cd. 2337 (1904), 5.

62 Reeves, Magdalen S.P. (1913) Round About a Pound a Week, 103.

63 ibid., 97–8.

64 Roberts, Robert (1971) The Classic Slum. SalfordLife in the First Quarter of the Century, 85–6.

65 Cantlie, James (1885) Degeneracy amongst Londoners, quoted in G. Stedman Jones (1976) Outcast London, 127.

66 Oddy, D.J. (1982) The health of the people‘, in Theo Barker and Michael Drake (eds) Population and Society, 1850–1980, 123 (Table 1).

67 Hurt, John (1985) ‘Feeding the hungry schoolchild in the first half of the twentieth century’, in Diet and Health in Modern Britain, op. cit., 178 et seq.