7

7

Rural England: romance and reality

He used to tramp off to his work while town folk were abed,

With nothing in his belly but a slice or two of bread;

He dined upon potatoes, and he never dreamed of meat

Except a lump of bacon fat sometimes by way of treat.

Agricultural Labourers’ Union Ballad1

The cottage homes of England,

By thousands on her plains,

They are smiling o’er the silvery brook

And round the hamlet fanes.

From glowing orchards forth they peep,

Each from its nook of leaves.

And fearless there the lowly sleep

As the birds beneath the eaves.

From a poem by Felicia Hemans

Francis George Heath, writing on British Rural Life and Labour in 1911, entitled one of the chapters of his book ‘Romance and reality’. Nearly forty years before, in 1873, he had tramped the west country ‘pencil and notebook in hand’ to investigate the condition of the rural labourer, and he recalled an episode when one day he stumbled by chance on an idyllic scene:

Away from the main road, a lane led up to the right, and a peep over the hedge revealed just a glimpse of the whitewashed walls and the low thatched roof of a cottage… Down one side of the lane gurgled a limpid stream of water…. Another turning, this time round to the left after a few steps up the lane, and a pretty sight met my view. Straight in front a narrow path led up under a kind of vista. On the right of this path there was a line of creeper-bound cottages, eighteen in all… Facing the cottages was a row of little gardens overshadowed by fruit trees. Here and there rustic beehives were scattered over these gardens which contained flowers and shrubs in addition to their little crops of vegetables. The walls of some of the cottages were almost hidden by the creepers which trailed upon them. The little ‘nook’ was shut in on almost every side by orchards.

But unlike Mrs Hemans, Heath penetrated inside one of ‘the cottage homes of England’. At No. 1 lived a carter, his wife, his bedridden mother, and his family of five children, only one of whom, at nine-and-a-half, was old enough to work. The carter earned 10s a week, less £3 5s Od a year for the rent of a tiny potato ground, less 1 Os a year for rates – which included a gas rate for the adjoining parish. The oldest boy earned 5d a day and a pint of cider. The family existed in abject poverty and misery. The roof leaked and there were broken panes in the windows. In the two bedrooms, heaps of rags served as bedclothes. Some of the children had no shoes.2

Throughout Victorian times, and later, romantic myths about the countryside and countrymen persisted. Writers eulogized the beauty of country mansions and the pleasures of rural recreation3 while making no reference to the work and wages of the labourer who made English agriculture the profitable plaything of the rich, as well as the tidiest in Europe: others proclaimed the benefits of a feudal relationship, the kindness and concern of landlords towards an ungrateful peasantry whose only return was a sullen deference. ‘Never once in all my observation,’ wrote Richard Jefferies to The Times in 1872, ‘have I heard a labouring man or woman make a grateful remark, and yet I can confidently say that there is no class of persons in England who receive so many attentions and benefits from their superiors as the agricultural labourers.’4 A romantic nostalgia for the past clouded the judgement of such writers, who claimed to have the interests of the countryside at heart, as well as the memories of some labourers when attempting to recall the stories of their own lives. An old Hampshire woman told W. H. Hudson in 1902 that

Nothing’s good enough now unless you buys it in a public house or a shop. It wasn’t so when I was a girl. We did everything for ourselves, and it were better, I tell ’e. We kep’ a pig then – so did everyone; and the pork and brawn it were good, not like what we buy now. We put it mostly in brine, and let it be for months; and when we took it out and boiled it, it were red as a cherry and white as milk, and it melted just like butter in your mouth…. And we didn’t drink no tea then… . We had beer for breakfast then, and it did us good. It were better than all these nasty cocoa stuffs we drinks now…. And we had a brick oven then and could put a pie in and a loaf and whatever we wanted and it were proper vittals.5

If memory did not play her false, she was an unusually fortunate young girl. This was not the experience of most agricultural labourers in the middle of last century.

The general state of the rural labourer between 1850 and 1914 was one of chronic poverty and want, acute at the beginning of the period, slightly alleviated towards the end of it. His real position was summed up accurately enough by Sidney Godolphin Osborne when he remarked, ‘The constant wonder is that the labourer can live at all,’ and even more succinctly by Canon Girdlestone’s comment that labourers ‘did not live in the proper sense of the word, they merely didn’t die’. The condition of the labourer was strangely independent of the fortunes of agriculture as a whole – or rather, it varied inversely with such fluctuations; when farming was at its most prosperous in the middle decades of the century the labourer was at his poorest, and only in the period of agricultural depression after 1874 was a dawning improvement discernible. In such conditions the labourer could feel little concern or sympathy for the fate of his employer. Nor, last of all workers to be enfranchised, in 1884, could he expect Parliament to be very conscious of his interests. Speaking of the agricultural legislation of the period in its effects on labour, Dr W. Hasbach wrote, ‘Such reforms as were effected were more or less accidental and unintentional. Not till towards its end do we come upon direct, purposeful and effective action definitely concerned with the problem of the agricultural labourer.’6 Although, in the long view, the new Poor Law of 1834, the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, and the Education Acts of 1870–6 may all have been necessary conditions of the labourer’s progress, their immediate effect in each case was adverse, while the legislative campaigns in favour of allotments and against the gang system were either failures or not directly beneficial to the adult worker. To a considerable extent the labourer was the instrument of his own ultimate improvement, both by leaving the land which would not yield him a reasonable livelihood, and by forming effective trade unions for those who stayed behind. A rural exodus of considerable proportions was one consistent feature of this period, the total number of agricultural workers falling from 965,514 in 1851 to 643,117 in 1911 (see Table 15). For the last thirty years of the century, 100,000 workers left the land in each decade to swell the populations of towns, colonies, and the United States.

The period of agricultural history from 1850 to 1874 has been variously described as ‘The Golden Age’ or that of ‘High Farming’.7 The gloomy prognostications about the effects of the repeal of the Corn Laws were not fulfilled in these years; England was not swamped with foreign corn, but in expectation of fierce competition landlords introduced improvements which, for a time, made English farming the model for Europe and the world. Improvements in seeds, manures, tools, machinery, and breeds of cattle, the introducion of methods of land drainage and the application of new means of communication and new knowledge of science all contributed to the intensity and efficiency of farming practice. ‘The traveller who passes today through almost derelict districts,’ wrote Hasbach in a famous passage, ‘must find himself wishing that he had seen these same places in the days when drain-pipes lay heaped upon the fields, great sacks of guano stood in serried ranks, the newest machines were busily at work in field or meadow, and the beasts, in clean and airy

Table 15 The agricultural population. Census returns of those who were engaged on farms in England and Wales in 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911

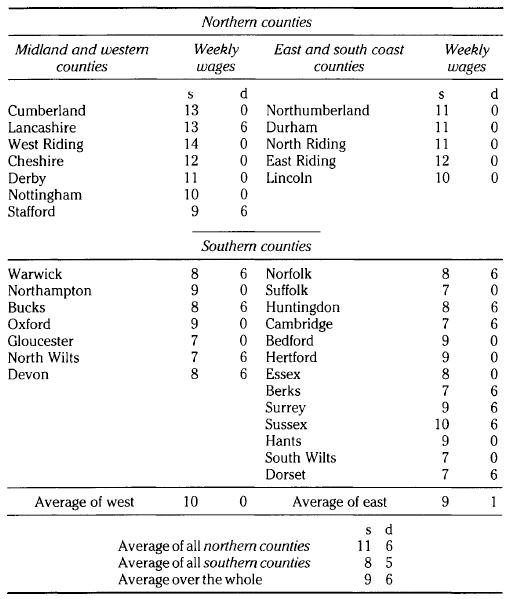

Table 16 The rate of agricultural wages in 1850–51

stables, were fattened on foods hitherto unknown.’8

The beasts were more fortunate than the men who tended them. When James Caird made his detailed survey of English agriculture for The Times in 1850–1, he found that the wages of adult labourers varied from 7s a week in south Wiltshire to 15s a week in parts of Lancashire: the average for the whole country was 9s 6d, but for the northern counties it was 11s 6d against 8s 5d for the southern.9 This disparity between the earnings of those in the corn counties and those in the mixed husbandry counties of the north was due, he believed, to the proximity there of manufacturing and mining industry, which offered competing and better paid employment for the labourer. When Arthur Young calculated wages in 1770, they had been slightly higher in the south than in the north (7s 6d as against 6s 9d): in Berkshire and Wiltshire they were therefore precisely the same in 1851 as they had been eighty years earlier, and in Suffolk absolutely less. Caird concluded that ‘in some of the southern counties… wages are insufficient for healthy sustenance’, and, in consequence, more labourers were still dependent on the Union for poor relief sixteen years after the Poor Law Amendment Act. Wiltshire had the highest proportion of paupers to the total population with 16.1 per cent; Dorset had 15.7 per cent and Oxford 15.1 per cent, but the average for the northern counties was only 6.2 per cent. Caird also found that the poverty of the southern labourer was clearly evidenced by the character of his diet. A Dorset labourer earning 6s a week and paying Is for his cottage, described a day’s food:

After doing up his horses, he takes breakfast, which is made of flour with a little butter and water ‘from the tea-kettle’ poured over it. He takes with him to the field a piece of bread and (if he has not a growing family, and can afford it) cheese to eat at midday. He returns home in the afternoon to a few potatoes, and possibly a little bacon, though only those who are better off can afford this. The supper very commonly consists of bread and water. … Beer is given by the master in haytime and harvest.10

On large estates wages were generally a shilling higher, and in addition to a beer allowance of a gallon a day in the harvest-field the labourer received turf and brushwood for fuel and often a small potato-ground. In Suffolk – another poor county – a week’s budget for man and wife (no children in this case) consisted of the items shown below.11 ‘Sundries’ would have to include clothing, shoes, soap and candles, yeast and salt, household replacements and medicine, besides any additional food which such a scanty diet required.

| s d | |||

| 1 stone of flour | 1 10 | ||

| ½ lb of butter | 6 | ||

| 1 lb of cheese | 7 ½ | ||

| 1 ½ of tea | 4 ½ | ||

| ½ lb of sugar | 2 | ||

| 3 6 | |||

| Rent of cottage | 2 0 | ||

| 5 6 | |||

| Weekly wages | 8 0 | ||

| Balance for sundries | 2s 6d |

The contemporary evidence suggests that only slight improvements in the labourer’s position occurred during the decade which opened with the Great Exhibition. Prices of necessaries continued high – especially during the shortage years of the Crimean War, when wheat reached 72s 5d (1854) and 74s 8d (1855), and the combination of this with low wages made things as bad as they had been in the 1840s or earlier. Alexander Somerville reported of Somerset labourers in 1852 that:

For years past their daily diet is potatoes for breakfast, dinner and supper, and potatoes only. This year they are not living on potatoes because they have none (the crop failed) and the wretched farm labourers are now existing on half diet, made of barley, wheat, turnips, cabbages and such small allowance of bread as small wages will procure.12

Joseph Arch remembered eating barley bread during his boyhood in Warwickshire about this time:

and even barley loaves were all too scarce … The food we could get was of very poor quality, and there was far too little of it. Meat was rarely, if ever, to be seen on the labourer’s table…. In many a household even a morsel of bacon was considered a luxury.

But Arch’s father grew carrots and turnips in his garden, and the family never stole, or begged for food at the rectory as many villagers had to do.13 Diet in Norfolk at this time seems to have been a little better and rather more varied, though still largely meatless:

Wheaten bread of the best quality was the principal food; it appeared at every meal with, or without, a little butter or cheese, and an onion or apple. If there was time and inclination for cooking, the principal meal came at the end of the day. There was the traditional Norfolk dumpling, made like bread with yeast, and dropped into boiling water after it had risen before the fire; potatoes or cabbage, if they were grown in the garden, completed the dish, unless earnings were sufficient for a little bacon or meat perhaps once a week. Herrings made a variation, and meat and fruit pies appeared on special occasions like harvest time. This diet [says Miss Springall]iseems to have changed very little between 1834 and 1876.14

The labourer’s dietary position was, of course, influenced by factors other than wages. The wide extent of truck (payment in kind), which employers claimed was a hidden advantage to their workers, in many cases merely forced them to take inferior goods at inflated prices or limited the way in which they could spend their earnings. The Rev. Lord Sidney Godolphin Osborne described the practice in his native Dorset, where on some estates labourers were paid ‘almost entirely on the truck system’. For best wheat they were charged 7s a bushel or 56s the quarter, and for the inferior ‘tailings’ 6s – ‘at least 1s a bushel too much’. This, with cottage rent at is, would absorb the whole of a labourer’s wage. But often the farmer would require his men to take inferior qualities of butter and cheese, which could not be sold in the market, or beef and mutton from diseased animals. ‘Many of us must even get in debt to them,’ one labourer told Osborne, ‘and then you see, Sir, we must go on.’15 The diseased mutton was the only ‘fresh’ meat which many labourers tasted, unless they dared to defy the Game Laws by snaring a rabbit or knocking a hare over the head. Many must have done this, either because they had a craving for meat which could not otherwise be satisfied, or because they had a natural love of sport with the added spice of beating the gamekeeper, but they took a terrible risk. The penalty for poaching was still transportation until 1857, and thereafter imprisonment or a heavy fine; and by a new law of 1862 a labourer who was seen after dark carrying any suspicious-looking bundle could be compulsorily searched by a police officer. It had been the custom for women cleaning turnips in the field to take two or three home with them as a perquisite, and farmers had tacitly recognized the custom, but after the new Act several women in Warwickshire were searched, charged with stealing turnips, and fined. On another occasion in 1873 a labourer was fined £I 9s 6d for picking a little liverwort for his sick wife. In these conditions it is probable that no more than a very small proportion of labourers were systematic poachers: only those who did not have a regular job to lose, who lived in ‘open’ parishes or on the edges of commons or woods, might make a regular practice of it. The old labourer who told John Halsham that as a boy he had lived with his father in the woods, ‘and most days we’d a hare… or a pheasant he’d pick up a day or two after a shoot, and we’d wild duck sometimes, and I got trout out of the brook’,16 was exceptionally lucky and quite untypical.

Personal evidence of this kind is useful, though a great deal must be accumulated before any general picture emerges. Fortunately, it can be supplemented by evidence from the first national food inquiry ever undertaken in Britain, conducted in 1863 by Dr Edward Smith on behalf of the Medical Officer of the Privy Council (Sir John Simon) and published as an appendix to the Sixth Report. This was a remarkable pioneering survey which opened up an entirely new sphere of sanitary inquiry. Smith had previously investigated the physical condition and state of nourishment of Lancashire workers during the Cotton Famine, in the course of which he had estimated the weekly minimum of food necessary for subsistence and sufficient to prevent diseases bred by starvation: thus thirty years or more before the surveys of Booth and Rowntree he had invented the concept of a ‘minimum subsistence level’ below which civilized life was not possible, and based not merely on crude earnings but on the nutritional value of food. As then calculated, his estimate of minimum subsistence for an adult was 28,600 grains of carbonaceous and 1,330 grains of nitrogenous foods weekly, roughly equivalent to about 2,760 kilocalories and 70 g of protein a day.17

His inquiry of 1863 covered the food of ‘the poorer labouring classes’, in which category he included farm labourers and certain badly paid domestic workers such as silk-weavers, shoemakers, stocking and gloveweavers, and needlewomen. The families of 370 English labourers from every county except Herefordshire were examined, either by Smith personally or by other ‘competent persons’, who included doctors and boards of guardians, and there seems no reason to doubt that the findings were reasonably representative. Although it was shown that the labourer’s diet was on the whole superior to that of the indoor workers, one surprising conclusion was that Welsh, Scottish, and Irish farm labourers were all better fed than the English, and in particular consumed more milk. On average, however, the English labourer’s diet was considerably above the minimum subsistence level:

| Carbonaceous foods | Nitrogenous foods | |

| England | 40,673 grains | 1,594 grains |

| Wales | 48,354 grains | 2,031 grains |

| Scotland | 48,980 grains | 2,348 grains |

| Ireland | 43,366 grains | 2,434 grains |

Even in the lowest-fed counties, Somerset, Wiltshire, and Norfolk, the carbonaceous content was more than 31,000 grains, but in ten (Berkshire, Rutland, Oxfordshire, Hampshire, Staffordshire, Somerset, Cornwall, Wiltshire, Cheshire, and Essex) the nitrogenous content was below the minimum. Again, Smith’s inquiry demonstrated very clearly the difference in standard between north and south, Northumberland, Durham, and Cumberland having a particularly good and Wiltshire, Dorset, and Somerset a particularly bad nutritional record. Other significant conclusions were that, although agricultural labourers as a class were not badly fed, their wives and children frequently were, as the lion’s share of food went to the bread-winner; that his position was particularly unfavourable when there were several children under ten years of age, or where his wife could find no by-employment, where the house rent was high, or where vegetables could not be grown.

Turning to the consumption of particular foods, Smith found, as may be expected, that bread was the principal article of subsistence, being eaten at the average rate of 12 1/4 lb per adult weekly, or 55 3/4 lb per family: the lowest consumption (less than 10 lb) was in Cornwall, the highest (more than 15 lb) in Northumberland. The extent to which domestic baking had declined by this time was shown by the fact that 30 per cent of families bought bakers’ bread exclusively, and another 50 per cent used it as an adjunct: it appears that it had practically died out in the poor southwestern and southern counties and only survived strongly in the more prosperous north. Where flour was bought for baking it was almost everywhere the white wheaten flour known as ’seconds‘, and in only one of the 370 cases investigated was it whole brown meal; white bread was preferred because it was more palatable with little or no butter or other addition, and because it was less purgative, and it is interesting to find that Smith defended its use as ’based upon principles of sound economy, both as regards the cost of food and the nutriment which the young and old members of a family can derive from it‘.18 The only other meal of any importance was oatmeal, purchased occasionally by 20 per cent of families mainly for making gruel, but used for making cake only in Cumberland, Westmorland, and Northumberland. It was now as expensive as wheat flour, and consequently had been given up in Derbyshire and other areas where it was formerly popular. Small quantities of dried peas and rice found their way into the majority of households, mainly in the wintertime in place of fresh vegetables.

It is clear from Smith’s report that the second food of the English labourer was potatoes, not meat. They were consumed at the rate of 6 lb per adult weekly, or 27 lb per family, and 87 per cent of households used them. The average consumption figure is perhaps rather meaningless as the use of potatoes depended largely on the availability of allotments at a reasonable rental, and where a quarter- or half-acre potato-ground could be had for £1 or £2 a year, the consumption was very much heavier. In such cases 56 lb per family weekly was not uncommon. Again, Smith approved of their general adoption, chiefly on the ground that cooked potatoes made a hot dinner or supper when added to the morsel of meat available, which ‘otherwise would be a dry, cold and uninviting meal’. Meat was, in fact, a luxury in the labourer’s diet. Each adult consumed on average only 16 oz each week, and Smith included both fresh meat and bacon in the category since he found that they were regarded as interchangeable. Thirty per cent of all families never ate butcher’s meat. Again, the variation from the average consumption was very great – in Salop, Essex, Somerset, Wiltshire and Norfolk less than 7 oz were consumed by adults weekly, while in Durham, Lancashire, Northampton, Surrey, and Yorkshire it was more than 24 oz, and in Northumberland as much as 35 oz. When fresh meat was eaten it was generally beef or mutton, although Smith found that sheep’s head and pluck were frequently used by poorer families, or half a cow’s head would provide Sunday dinner and broth for the children throughout the week as well as dripping. Pickled pork was almost the only meat available in Dorset, Somerset, and the eastern counties, but this, like bacon, had the great advantage that it did not shrink when cooked and could be cut up easily into small pieces for flavouring potatoes and vegetables. Whenever possible, meat was eaten at the Sunday dinner, which was often the only occasion in the week when the whole family dined together; what was left was reserved for the husband, who took a little with him for dinner in the fields or ate it for supper at night, his wife and children existing mainly on bread, potatoes, and weak tea. Smith remarked that ‘This is not only acquiesced in by the wife, but felt by her to be right, and even necessary for the maintenance of the family…. The important practical fact is, however, well established, that the labourer eats meat or bacon almost daily, whilst his wife and children may eat it but once a week’19

Of other foods the most widely used was sugar, at 7 ½ oz for adults weekly and 33¾ oz per family. Much of it went to sweeten tea, though in the poorest counties this was drunk without either sugar or milk, and an increasing amount was in the form of treacle, which at 4d a pound was a cheap substitute for butter. Sugar in 1863 was still in a transitional stage, regarded by better-off families as a necessity but by the poorer as a luxury. Tea was by now a necessity, 99 per cent of all the families consuming it at the average rate of ½ oz per adult weekly, 2 1/4 oz per family. Coffee was much less popular, partly because it needed more preparation and partly because it was less palatable without the addition of sugar or milk, but tea had become the staple drink of wife and children, often being taken (very weak) two or three times a day. The husband drank his beer or cider ‘allowance’ in the field, and tried to keep some back to bring home with him for supper. A surprising discovery was the small quantity of dairy produce which labourers were able to obtain, often, it seems, because farmers would not take the trouble to sell it in the small amounts which could be afforded, preferring to dispose of the milk and butter off the farm in bulk to nearby towns. Consequently the average quantity of milk consumed was only 1.6 pints per adult weekly, of butter, dripping, and suet combined 5 ½ oz, and of cheese 5 ½ oz: only in comparatively few families was butter eaten every day, ‘since’, said Smith, ‘the poorer for the most part had two days a week in which the children ate dry bread’. They and their mothers were the chief casualties of the labourer’s low standard of living.

Translated into modern nutritional terms, the average quantities of food in the labourer’s family budget produced 2,760 kilocalories per person per day, 70 g of protein, 54 g of fat, 0.48 g of calcium, and 15.9 mg of iron. Smith’s diets did not record the ages of children, and the calculations are therefore derived from a straight division of the total family food by the number in the family. We know that the husband received the ‘lion’s share’ of some foods – particularly meat – and, indeed, 2,760 kilocalories would not have provided enough energy for a man in heavy agricultural work by at least 1,000 kilocalories a day. It follows that his wife and children were receiving less than the calculated averages by unknown, but possibly large, amounts. Professor John Yudkin has commented on this: The figures for calorie intake suggest that they were low enough both to affect growth and to restrict physical output. Quite apart from long hours and poor working conditions, the small intake of food must have contributed to a state of chronic exhaustion of the workers.‘20 Added to this, the protein intake was almost certainly inadequate for pregnant and lactating women and for growing children and adolescents, while the amount of calcium was very low by modern standards.

The bare statistics of consumption do not indicate much about the kind of meals which labourers actually ate. Smith made careful inquiry into this, too, and the following are typical examples of daily fare from different parts of the country:

DEVON (Case No. 135). Breakfast and supper – tea-kettle broth (bread, hot water, salt, and 1/3 pint of milk), bread and treacle. Dinner – pudding (flour, salt and water), vegetables, and fresh meat; no bread.

(Case No. 163). Breakfast – wife has tea, bread and butter; husband, teakettle broth with dripping or butter added, and with or without milk, also bread, treacle or cheese. Dinner – fried bacon and vegetables or bacon pie with potatoes and bread. Supper – tea, or milk and water, with bread, cheese and butter.

DORSET (Case No. 191). Breakfast – water broth, bread, butter, tea with milk.

Dinner – husband has bread and cheese: family take tea besides. Supper – hot fried bacon and cabbage, or bread and cheese.

WILTSHIRE (Case No. 211). Breakfast – water broth, bread and butter.

Dinner – husband and children have bacon (sometimes), cabbage, bread and butter. Wife has tea. Supper – potatoes or rice.

(Case No. 212). Breakfast – sop, bread, and sometimes butter. Dinner – bread and cheese. Supper – onions, bread, butter or cheese.

LINCOLNSHIRE (Case No. 248). Breakfast – milk gruel, or bread and water, or tea and bread. Dinner – meat for husband only; others vegetables only. Tea and supper – bread or potatoes.

NOTTINGHAMSHIRE (Case No. 255). Breakfast – children – thickened milk; others-tea or coffee, and bread and butter with cheese sometimes.

Dinner – little meat, and potatoes. Supper – bacon or tea.

DERBYSHIRE (Case No. 281). Breakfast – coffee, bread and butter. Dinner – hot meat, vegetables and pudding daily. Tea – tea, bread and butter. Supper – hot, when not hot dinner.

CUMBERLAND (Case No. 301). Breakfast – husband – oatmeal and milk porridge: the others – tea, bread, butter and cheese. Dinner – meat and potatoes daily, bread, cheese and milk. Supper – boiled milk, followed by tea, bread, butter and cheese.

LANCASHIRE (Case No. 304). Breakfast – milk porridge, coffee, bread and butter.

Dinner – meat and potatoes, or meat pie, rice pudding or a baked pudding; the husband takes ale, bread and cheese. Supper – tea, toasted cheese, and bacon instead of butter.

YORKSHIRE (Case No. 471). Breakfast – husband – milk and bread: family – tea, bread and butter. Dinner – husband – bacon daily: others – three days weekly, potatoes or bread, tea. Tea – tea, bread and butter.21

Dr Smith’s report indicates that labourers’ wages had moved up somewhat since Caird’s survey a dozen years before – by a mere 4 per cent in what was already a high-wage county like Lancashire, but by as much as 52 per cent in Surrey and 58 per cent in Gloucestershire. The average rise over all counties was 28 per cent, and it is noticeable that the gap between north and south had closed somewhat. But although the trend was upward, it was from a miserably low base.

In 1867, as in 1843, a Royal Commission inquired into the employment of women and children in agriculture22 and the reports of the numerous commissioners are a terrible indictment of the conditions of crushing poverty still prevailing in an era of agricultural prosperity. Of the eastern and south-eastern counties, the Rev. J. Fraser said that ‘the dominant fact over the whole district was the insufficiency of wages, which varied between ten and thirteen shillings a week’: the inevitable result was the extensive employment of women, often in organized gangs, and of children from the age of six or seven upwards. Again, conditions in the northern counties were in sharp contrast, and Northumberland, where the yearly hiring and yearly payment still persisted, stood out as a bright spot. Here children were only employed in summer, and not under eleven years of age; regular work began at about fourteen, so that many had an opportunity of acquiring some education, which was rare in the south. As far south as Derbyshire the labourer could still earn his 15s a week, but in Dorset and Devonshire he fell back into penury and debt with 8s. It seems likely, however, that shortly after this time wages again took a slight upward turn, partly, it was reported, as a result of agitation by the newly formed Agricultural Labourers‘ Unions: an official inquiry of 1872 showed a range of day labourers’ wages from 10s 4d (Dorset) to 20s 6d (Durham), the mean for England and Wales being 14s 8d.23 The reliability of such estimates is doubtful, and in any case the relevant statistic is not so much the labourer’s wage as the family earnings. When wife and children also worked in the fields, as was often the case, or at domestic industries such as the stocking frame, seaming, glove-stitching or straw-plaiting, T.E. Kebbel believed that ‘the average weekly cash earnings . .. may be set down probably at 18s a week, exclusive of “allowances”, and, if harvest money is added, at £’.24 A case was mentioned in the 1867 Report of a labourer near Market Harborough whose total earnings for the year were £103 9s Od: he was exceptionally fortunate in having three sons between the ages of fourteen and nineteen who could all contribute usefully to the family budget. But, as the author of The Seven Ages of a Village Pauper explained, the worst times in a labourer’s life were, first, when he was raising a growing family, his wife unable to work and often incurring medical expenses and, second, when in old age he could only work casually, or not at all. In this Oxfordshire village, although only one in every ten of the inhabitants were in receipt of poor relief at any given time, between one-half and three-quarters of all were forced to live ‘on the rates’ at some period in their lives.25

Although the labourer’s position at this period could perhaps nowhere be described as comfortable, there were clearly important variations in the degrees of his discomfort. As we have seen, his position depended partly on region, on the size and age of his family, and on the extent to which they could contribute to the household budget. But, equally important, was the skill of the housewife in adapting a limited range of simple foodstuffs into nourishing and palatable meals, even when income and cooking facilities were very restricted. At Harpenden in Hertfordshire in the 1860s and 1870s, for example, the labourer’s wage was 11s to 13s a week, supplemented by some straw-plaiting by his family. The cottages here rarely had an oven or range, so the bulk of food was prepared by boiling in a large iron pot over the open fire, or by frying: potatoes, greens, flour dumplings, and whatever meat was available were all cooked together, though usually in separate nets which allowed the cooking time of different items to be controlled. The dumplings, with a filling of streaky bacon, pickled pork or liver, mixed with onion and potato, were particularly important for the man’s dinner-basket in the field, where they were either eaten cold or heated over a gypsy fire; the basket also contained some large ‘door-steps’ of bread, one or two raw onions, a horn of salt, and a can of cold tea. Some of the rows of cottages had a communal bakehouse at the rear, and some home-baked their own bread, usually fortnightly. Most of the men had allotments of ten or twenty poles, rented at 3d a pole a year, and many kept a pig, or occasionally two: pickled pork was a great favourite, and accounted for around two-thirds of all the meat eaten. Most of the farmers allowed gleaning after harvest, and the women and children could gather enough wheat to produce from two to seven bushels of flour, depending on the number in the family.26

Budgets of the 1870s show no great change from the earlier period, except that the region of most wretched conditions seems to have shifted a little farther into the south-west. Up until now Dorset had had the reputation of greatest poverty, but Francis George Heath discovered even worse conditions in Somerset when he made his investigation in 1874. Here, a typical young married labourer earned at day-work and extra piece-work an annual total of £31 16s 6d. His expenses for his family of four children were:27

| Per annum | £ | s | d | |

| Rent (2s per week) | 5 | 4 | 0 | |

| Poor rates | 7 | 6 | ||

| Tithes | 1 | 6 | ||

| Coal (1 cwt per week) | 2 | 12 | 10 | |

| Shoes and mending | 2 | 5 | 0 | |

| Bread (4s 6d per week) | 11 | 14 | 0 | |

| Potato-ground (1/4 acre) | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Seed potatoes | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Club pay | 12 | 0 | ||

| Soap | 10 | 10 | ||

| Tea (3d per week) | 13 | 0 | ||

| Candles | 7 | 6 | ||

| Butter (1/4 lb per week) | 17 | 14 | ||

| Treacle (½ lb per week) | 6 | 6 | ||

| Matches, thread and tape | 3 | 6 | ||

| Broom and salt | 2 | 0 | ||

| Cups, saucers, plates | 1 | 8 | ||

| Children’s schooling (Id per week each) | 17 | 4 | ||

| Tools and repairs | 1 | 18 | 1 | |

| ________________________________________________________ | ||||

| Total | £31 | 13s | 9d | |

| ________________________________________________________ | ||||

| Balance | 2s | 9d | ||

In this household, as in many described by Heath, there was no meat from one year’s end to another. Few could afford to pay Is a pound for it at the village shop, and those who did manage to get any generally did so by fattening their own pig, which Heath described as ‘the live savings bank’; by the time the pig was fattened and ready for killing half often had to be sacrificed to pay the tradesman who had supplied its meal, but usually there was some pork and bacon left for the family besides enough cash to buy another ‘suckling’.

Keeping a pig was a sure sign of a standard of living somewhat above the poverty line. Flora Thompson described how in her north Oxfordshire village all the family would sacrifice for the sake of the pig, and much time and trouble would be spent saving scraps and foraging for it:

The family pig was everybody’s pride and everybody’s business. Mother spent hours boiling up the little taturs‘ to mash and mix with the pot-liquor . . . and help out the expensive barley meal. The children, on their way home from school, would fill their arms with sow thistle, dandelion and choice long grass, or roam along the hedgerows on wet evenings collecting snails in a pail for the pig’s supper. These piggy crunched up with great relish.28

All the labour of feeding, killing, and preparing the various joints and products was well worth while, however: when the remains of the pig were hung up on a wooden rack across the kitchen ceiling ‘that was a better picture than an oil painting’.29

But at Athelney in Somerset Edwin H. earned 9s a week to provide for himself, his wife, and eight young children: they had not tasted meat for six months, and at 7d the quartern loaf, baker’s bread was a luxury they could not afford. Here the wife bought meal and made a coarse bread at home.30 And in North Devon, Canon Girdlestone, who was urging migration to the higher earnings of the north as the only solution for the labourer, described conditions as follows:

Wages are for labourers 8s or 9s a week, with two or one and a half quarts of cider daily, valued at 2s per week, but much over-valued. Carters and shepherds get Is a week more, or else a cottage rent free. The labourer has no privileges whatever. He rents his potato-ground at a high rate. Though fuel is said to be given to him he really pays its full value by grubbing up for it in old hedges in after-hours. In wet weather or in sickness his wages entirely cease so that he seldom makes a full week. The cottages, as a rule, are not fit to house pigs in. The labourer breakfasts on tea-kettle broth, hot water poured on bread and flavoured with onions; dines on bread and hard cheese at 2d a pound, with cider very washy and sour, and sups on potatoes or cabbage greased with a tiny bit of fat bacon. He seldom more than sees or smells butcher’s meat. He is long lived, but in the prime of life ‘crippled up’, i.e. disabled by rheumatism, the result of wet clothes with no fire to dry them by for use next morning, poor living and sour cider. Then he has to work for 4s or 5s per week, supplemented scantily from the rates, and, at last, to come for the rest of his life on the rates entirely. Such is, I will not call it the life, but the existence or vegetation of the Devon peasant.31

The prosperity of the ‘Golden Age’ came to a sudden end in 1874 when, for the first time, free trade exposed English agriculture to the competition of the world’s grain and meat producers, and from this time until 1896 there followed a period of almost uninterrupted depression, deepened at times by domestic catastrophes such as bad harvests and cattle plagues. With great stretches of land going out of cultivation and much more under-cultivated, the immediate effect of the agricultural crisis on the worker was to reduce the demand for labour and to lower wages, sometimes by Is, occasionally by 2s, a week; not surprisingly, the rural exodus continued at an increased pace, and farmers complained that with the departure of their best labourers they now had to pay more to get the same quantity of work done. Nor was the labourer yet helped by falling prices which, on average, remained the same between 1871 and 1880 as in the previous decade – meat prices, in fact, were rising until the late 1870s. A witness before the Royal Commission on Agricultural Depression of 1882 summed up the effects: ‘I should say that the landlord suffers least … that the farmer suffers most, but that he feels his suffering less than the labourer. To the labourer it is a question really of less food, to the farmer it is not absolutely a question of bread, it is comforts or no comforts.’32

Francis Heath entitled the final chapter of his book The English Peasantry, written in 1874, The future of the English peasantry‘, and prognosticated that, ’A happier condition of life for the immediate future of our peasants may be anticipated without indulgence in any visionary ideas.‘ Revisiting the four western counties of Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset, and Devon in 1880 he was already able to report on ’dawning improvement‘. Although 10s or 11s a week was still the average wage in this part of England, ’privileges‘ were beginning to disappear, or, where they survived, were no longer regarded as part-payment of the wage, and some improvement in cottage accommodation was noticeable. The character of diet was also on the turn. From Dorset it was reported:

the labourer decidedly lives better than he did, for he ‘sees’, ‘smells’ and ‘tastes’ meat regularly, instead of once a week as formerly. A slice of fat bacon no longer satisfies.

In Devonshire the usual fare was:

for breakfast, ‘broth’ made of fat, bread and water; for the mid-day meal perhaps a little bread and cheese or potatoes and pork – sometimes, for a change, a little dried fish instead of pork; for the evening meal a cup of tea with dried bread. Pies and pasties are the great feature of the Cornish diet. The ordinary pasty of the Cornish labourer is clean, wholesome and nutritious.

And from Somerset a correspondent reported that the labourer’s fare consisted of:

Breakfast (before seven a.m.) of bread and bacon or dripping, with fried potatoes; a lunch at about ten or eleven of bread and cheese and cider; dinner, if taken in the fields, of bread and cold bacon or other cold meat, washed down with cider, or, if near enough to home, a dish of hot vegetables with a little meat. Further, the peasant has a slight meal of bread and cheese at about four o’clock and a substantial supper soon after leaving work, of hot vegetables with meat or fish of some kind, boiled or fried, and tea and bread and butter – the whole making a grand total of no inconsiderable amount, and which only fairly hard work and fresh air enable him to digest.33

In these and other budgets of the 1880s there is both more quantity and more variety, and the increasingly regular use of meat and fish is particularly significant. Although Canon Tuckwell’s estimated budget for a family of six which allowed 6 lb of meat weekly at 8d a pound may well be optimistic, it seems that some meat every day was now general, at any rate for the husband: the interesting thing about Tuckwell’s budget of 1885 is the fall in price of other foods – bread which could now be bought for 4d to 4d the quartern loaf, sugar at 3d a pound, and tea at 2s a pound. This supposedly typical family spent more on meat than on bread, and consumed half a pound of tea, two pounds of sugar, and a shilling’s worth of milk each week.34

While the agricultural industry continued to stagnate in the 1890s, the condition of the labourer continued to improve. The seven voluminous Reports of the Royal Commission on Labour which were published in 1893 can be summarized as follows: in the south of England the labourer’s position had improved compared with twenty-five years earlier, though in many parts it was still far from satisfactory; in the north, no change of any importance had taken place; money wages had been on the increase, and, generally speaking, employment had become more regular; women’s and children’s labour had greatly diminished; the exodus from the land had continued in almost every county. Actual wages still only averaged 13s 5 ½d a week, ranging from 10s in Wiltshire and Dorset to 18s in Lancashire and Cumberland, but the important point was that their purchasing power had increased because of the low price of provisions; moreover, shorter hours meant that the labourer had more leisure-time to devote to his allotment and so could raise more potatoes and vegetables than formerly.

The allotments movement had made considerable progress in most parts of the country, sometimes against the wishes of farmers who did not want their labourers to over-tire themselves when working on their own account, and even, as at Tysoe in Warwickshire, where the vicar thought that one-sixteenth of an acre was the right amount.35

Village co-operative societies, and vans sent round by nearby town societies, were also beginning to make a useful contribution to the food of the farm worker. ‘His standard of life is higher,’ said the Report: ‘He dresses better, he eats more butcher’s meat, he travels more, he reads more, and he drinks less.’36 But still there was the big gap in conditions between the purely agricultural counties of the south and east and those of the midlands and north, where nearness to industry and mining forced up wages to a competitive level. Commissioner Bear, who reported on Bedford, Hampshire, Huntingdon, and Sussex, said: ‘The agricultural labourers were never so well off as they have been during the last few years, [but] I am far from saying that the condition of the labourers, and especially that of the day-labourers, is satisfactory’; while the reporter on Berkshire, Oxfordshire, Shropshire, Cornwall, and Devon wrote that: ‘The large majority of labourers earn but a bare subsistence…. An immense number of them live in a chronic state of debt and anxiety, and depend to a lamentable extent upon charity.’37

The 2 oz of tea per family a week which Smith had found in 1863 had grown to ½ lb thirty years later, and many families now spent 1s 6d or more on tea and sugar weekly. This, the increased consumption of meat, butter and cheese, and the not infrequent mention of tinned salmon and sardines – even of labourers‘ wives buying a bottle of port wine – is all evidence of a generally increased standard of comfort and a trend towards a more standardized dietary among farmworkers. By the early 1890s Argentine beef and New Zealand lamb were appearing on labourers’ tables at Sunday dinner. But the improvement was not universal, and where wages were still low and there were many mouths to feed, little had changed. In three Berkshire labourers‘ budgets collected by the Royal Commission, bread took at least 6s a week, almost half the total earnings, and there was no fresh meat, only bacon.

Some of the Commission’s reporters even found signs of a deterioration in physique in parts of the country where traditional local foods were being abandoned. This was particularly noticeable in Northumberland, where the hinds and shepherds, formerly reared on a nutritious diet of milk, fat bacon, porridge, wholemeal bread, and butter, had been described in 1867 as a ‘splendid race’. In 1893 Arthur Fox wrote:

Owing to change of diet, especially since payment in kind was given up, there has been a falling off in strength and stamina… The children are being brought up on tea instead of milk and, without it, porridge is disliked and given up…. There is probably a good deal of truth in what one old man, William Stenhouse of Wark, said to me on this subject – ‘A man should eat the food of the country in which he is born. This foreign stuff, such as tea, is no forage for a man. Bannocks made of barley and peas made a man as hard as a brick. Men would take a lump of bannock out for the day, and drink water, but now they eat white bread and drink tea, and ain’t half so hard.’38

More, of course, were surviving.

By 1900 the indications were that the fortunes of the labourer were at last on the turn. So many had left the land that when Rider Haggard made his tour of Rural England in 1901 he found widespread depopulation and a scarcity of labour which had forced up wages even in a depressed county like Dorset:

I am told that at the annual hiring-fair just past the old positions were absolutely reversed, the farmers walking about and importuning the labourers to come and be hired instead of, as formerly, the labourers anxiously entreating the stolid farmers to take them on at any pittance. Their present life is almost without exception one of comfort, if the most ordinary thrift be observed. I could take you to the cottage of a shepherd, not many miles from here, that has brass rods and carpeting to the staircase, and from the open door of which you hear a piano strumming within. Of course, bicycles stand by the doorway…. The son of another labourer I know takes dancing lessons at a quadrille class in the neighbouring town.39

In 1902, Wilson Fox received detailed evidence from 114 investigators as to the wages and expenditure of labourers, which he published in a Board of Trade Report:40 the statistics were supplied by Local Government Board inspectors, members of local authorities, the clergy and tradesmen, as well as by agricultural labourers themselves. Of an average weekly wage, including all extra earnings, of 18s 6d, 73 per cent was spent on food in the way shown in Table 17.

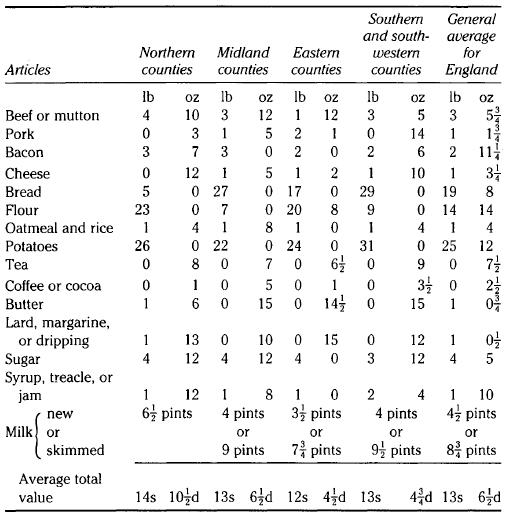

Table 17 Average consumption and cost of food by agricultural labourers’ families in England in 1902

Note:

The average family was taken to be the labourer, his wife and four children.

The table is revealing in a number of respects – for showing the increased consumption of fresh beef and mutton, which was now as large as that of pork and bacon, the ½ lb of tea, the 4 1/4 lb of sugar, the 1 lb of butter, and the 1 1/4 lb of cheese. Milk, too, had increased noticeably, while new items in the labourer’s diet included jam, syrup, margarine, and cocoa. The most striking fact, however, was that expenditure on meat was now, on average, greater than that on bread, and even in the low-wage counties of the south and east the two figures approached closely (see Table 18).

Table 17 does not include items ‘sometimes purchased’, for instance eggs and fish, tinned meats, currants, raisins, and pickles, nor does it take account of the vegetables and fruit grown on allotments. In all, there can be little doubt that substantial gains had been made in the labourer’s position, which were clearly reflected in the sample menus which the report contained:

CAMBRIDGESHIRE. Breakfast – bread, butter, cheese, tea. Dinner – meat, puddings, pork or bacon, potatoes and vegetables, cheese, perhaps beer (on Sundays, beef or mutton, puddings). Tea – bread, butter, cheese, tea; perhaps herrings or a little cold pork. Supper – bread, cheese, perhaps a glass of beer.

DERBYSHIRE. Weekdays – Breakfast – bread, butter, bacon, cheese, tea. Dinner – beef, pork or bacon, potatoes, tea or beer. Tea and supper – bread, butter, syrup, jam, tea; perhaps fish (fresh or tinned). Sundays – Breakfast – bread, butter, bacon, tea. Dinner-beef or pork, occasionally a fowl, potatoes, tea, beer. Tea – bread, butter, jam, tinned fish, tea; perhaps some fancy bread. Supper – the same sort of diet as tea, perhaps some beer.

DORSET. Breakfast – bread, butter, cheese, cold bacon, tea (Sundays, fried bacon). Dinner – boiled bacon, potatoes and other vegetables (Sundays, mutton or beef, with pudding); or salt pork, vegetables, dumplings (Sundays, a little fresh meat or pork). Tea – bread, butter or jam, cheese, tea (Sundays, cake). Supper – very rarely any, or if any, vegetables and salt pork.

Variations on this standard pattern included tarts and ‘toad-in-a-hole’ (a small loaf with a piece of bacon or other meat in the middle) in Devonshire, oatmeal porridge in the more northerly counties, onion and potato pudding in Huntingdonshire, stews in Staffordshire and Norfolk, fruit pies in Yorkshire. Nearly everywhere dumplings were eaten, and puddings of rice or tapioca; least frequently mentioned were milk and eggs, which were included only in Devonshire, and apparently only eaten there when they could be bought at eighteen for a shilling.

Francis Heath’s last volume on British Rural Life and Labour, published in 1911, painted an optimistic picture of the progress and prospects of the farm labourer which was in sharp contrast to his earlier surveys of 1880 and 1874. But the evidence on which Heath drew was the 1903 Report previously quoted, and there is reason to doubt whether the details there given as to earnings and expenditure, accurate or not at the time, were correct a few years later. In the years immediately before the First World War a number of social investigators, inspired by the pioneering work of Charles Booth and Seebohm Rowntree, were conducting detailed surveys of the labourer’s standard of life from personal investigation rather than the second-hand (and possibly biased) reports of farmers and boards of guardians, and with reference to every family in a particular village or area rather than a supposedly ‘typical’ statistical sample. Investigating every household in the single village of Ridgmount in Bedfordshire, H.H. Mann discovered that the average wage of a labourer, at full rates and including extras, was 14s 4d, not 16s 2d as given by the Board of Trade; he went on to state that 34.3 per cent of the older population of the village was without the means of sustaining life in a state of mere physical efficiency according to Rowntree’s standard.41 The Board of Trade, he argued, had not allowed enough when working out their averages for the far greater number of lower-grade labourers over foremen and other higher paid categories. An article by C.R. Buxton in the Contemporary Review for August 1912 showed that in Oxfordshire villages the average wage was between 10s and 12s a week, and that because of lost time in wet weather ‘hundreds of them have gone home at the week-end during the winter months with only 8s for the week’: in a family of two adults and three children, the average amount of money available for each person for each meal was 3/4d. In circumstances like this, where so little was available for food, it seems that the art of cooking had made little progress either: in her study of Corsley in Wiltshire Maude Davies found many families in which ‘the wife cooks only once or twice a week in the winter. She cooks oftener in summer when potatoes are more plentiful.’42 Finally, in the year before the outbreak of war, Seebohm Rowntree himself investigated in extreme detail the earnings and budgets of forty-two labourers from all parts of the country.43 Taking the weekly wage of 20s 6d, which Professor Atwater had calculated as the minimum necessary to maintain a family of two adults and three children (the dietary was more austere than that in the workhouse, containing no butcher’s meat, only a little bacon and tea, and no butter or eggs), he found that only in five northern counties (Northumberland, Durham, Westmorland, Lancashire, and Derbyshire) was ‘the wage paid by farmers sufficient to maintain a family of average size in a state of merely physical efficiency’. In many cases, of course, the labourer’s wage was supplemented by the earnings of other members of the family and by what he could raise on his allotment, but even allowing for all these additions, and for what was gained by charity, Rowntree discovered that in almost every case the nutritional value of the food consumed was less than that deemed necessary for a man engaged in only ‘moderate’ labour. In only one of the forty-two cases – a Yorkshire family having a combined income of 23s 2 ½d – was the minimum protein requirement of 125 g a day reached, and in only ten was the energy value minimum of 3,500 kilocalories attained. On average, there was a deficiency of 24 per cent of protein and 10 per cent of calories in the forty-two families.44

Underfeeding was still the lot of the majority of English labourers in 1914, and the Essex family who told Rowntree that they never felt ‘completely satisfied like’, except after Sunday dinner, was probably not untypical. The advances of the 1880s and 1890s were not, it seems, maintained subsequently, principally because price levels turned upwards after 1900, while wages remained practically stationary.45 If the labourer’s diet was less scanty and monotonous than it was in 1850, it was still nutritionally inadequate, especially in protein-rich foods such as meat, milk, eggs, and butter. In many of the households investigated by Rowntree, fresh meat was ‘for the man only’, in twenty of the forty-two no butter at all was eaten, and in the twenty-six which obtained fresh milk the consumption was only 5 ½ pints per family per week.46

The gains and losses over the previous half-century are not easy to assess. An Oxfordshire labourer with four young children and a wage of 8s a week represented the poorest of Rowntree’s case studies: he was able to buy 5 lb of frozen brisket a week for 2s Od, and 28 lb of bread for 3s 2 ½d – prices well below those of mid-century – while advances in food technology were evidenced by the pound of Quaker Oats (3d) and, less desirably, two pounds of margarine (Is) and condensed milk (3 ½d). The allotment movement had certainly contributed something to the labourer’s diet – Rowntree estimated that approximately one-twelfth of the food consumed was self-produced – although other attempts to ameliorate his position, such as the smallholdings campaign, had proved illusory. Perhaps the most helpful sign was that the plight of the agricultural labourer was at long last attracting widespread public interest and anxiety. The nation had recently been alarmed by reports of physical deterioration among town-dwellers. Now it discovered that its supposedly healthy country stock, the ‘backbone of England’ which could always be relied on to buttress the national stamina in times of need, was itself undernourished and economically inefficient. Was not a healthy peasant population socially desirable? Ought not the continued drift from the land be stopped, and, if so, how? A new awareness of the social problems of the countryside was dawning when the events of August 1914 blotted out any possibility of rural reform.

Notes

1 Quoted in Joseph Arch (1898) The Story of His Life, told by Himself, edited with a Preface by the Countess of Warwick, 98.

2 Heath, Francis George (1911), British Rural Life and Labour 181 et seq.

3 e.g. Howitt, William (1862) The Rural Life of England (3rd edn).

4 Village Politics: Addresses and Sermons on the Labour Question (1878), 85.

5 Hudson, W.H. Hampshire Days in G.E. Fussell (1949) The English Rural Labourer, His Home, Furniture, Clothing and Food from Tudor to Victorian Times, 128.

6 Hasbach, W. (1920) A History of the English Agricultural Labourer, trans. Ruth Kenyon, 217 et seq.

7 For a standard description of this period see Lord Ernie, English Farming Past and Present (new (6th) edition with Introductions by G.E. Fussell and O.R. McGregor, 1961), chap. XVII. More recent studies are in G.E. Mingay (ed.) (1981) The Victorian Countryside, 2 vols.

8 Hasbach, op. cit., 246.

9 Caird, James (1852) English Agriculture in 1850–51.

10 ibid., 84–5.

11 ibid., 147.

12 Somerville, Alexander (1852) The Whistler at the Plough.

13 Joseph Arch, op. cit., 10–15.

14 Springall, L. Marion (1936) Labouring Life in Norfolk Villages 1834–1914, 56–7.

15 White, Arnold (ed.) (nd) The Letters of S.G.O. 2 vols, I, 16–18.

16 Halsham, John (1897) Idlehurst.

17 Sixth Report of the Medical Officer of the Privy Council (1863). Appendix No.6: Report by Dr Edward Smith on the Food of the Poorer Labouring Classes in England, 232.

18 ibid., 239.

19 ibid., 249.

20 Barker, T.C., Oddy, D.J., and Yudkin, John (1970) The Dietary Surveys of Dr Edward Smith, 1862–3. A New Assessment, 46.

21 Sixth Report (1863), op. cit., 256 et seq.

22 Reports of the Commissioners on Children’s, Young Persons‘ and Women’s Employment in Agriculture, 1867–70. For an excellent summary of the Reports, see Hasbach, op. cit., Appendix VI, 404 et seq.

23 Earnings of Agricultural Labourers. Returns of the average rate of weekly earnings of agricultural labourers in the unions of England and Wales, SP 1873, (358) LIII.

24 Kebbel, T.E. (1870) The Agricultural Labourer: A Short Summary of His Position, 29.

25 Bartley, George C.T. (1874) The Seven Ages of a Village Pauper. Dedicated to One Million of Her Majesty’s Subjects whose Names are now unhappily and almost hopelessly inscribed as Paupers on the Parish Rolls of England.

26 Grey, Edwin (1934) Cottage Life in a Hertfordshire Village, repub. 1977, chap. 3, 96–127.

27 Heath, Francis George (1874) The English Peasantry, 41–2.

28 Thompson, Flora (1973) Lark Rise to Candleford (Penguin edn), 24.

29 Samuel, Raphael (ed.) (1975) Village Life and Labour, History Workshop Series, 200.

30 Heath (1874), op. cit., 79.

31 ibid., 99–100.

32 Quoted in Hasbach, op. cit., 295.

33 Heath (1911), op. cit., 286 et seq.

34 Tuckwell, Rev. Canon (1895) Reminiscences of a Radical Parson.

35 Ashby, M.K. (1974) Joseph Ashby of Tysoe, 1859–1919, 126.

36 Report of Royal Commission on Labour: The Agricultural Labourer, vol. I (England), C. 6894, I–XIII (1893), pt II, 44.

37 ibid., 46.

38 ibid.: Report by Arthur Wilson Fox (Assistant Commissioner) upon Poor Law Union of Glendale (Northumberland), 110.

39 Haggard, H. Rider (1902) Rural England. Being an account of agricultural and social researches arrived at in the year 1901 and 1902 2 vols, I, 282–3.

40 British and Foreign Trade and Industry; Memoranda, Statistical Tables and Charts prepared in the Board of Trade with Reference to various matters bearing on British and Foreign Trade and Industrial Conditions, Cd. 1761 (1903), XVIII: Consumption of Food and Cost of Living of Working Classes in the UK and certain Foreign Countries, 209 et seq.

41 Mann, H.H. (1904) ‘Life in an agricultural village’, Sociological Papers, quoted in F.E. Green (1913) The Tyranny of the Countryside, 228 et seq.

42 Davies, Maud F. (1909) Life in an English Village, 211.

43 Rowntree, B. Seebohm and Kendall, May (1913) How the Labourer Lives. A Study of the Rural Labour Problem.

44 ibid., ‘Adequacy of diet’, 299 et seq.

45 Rowntree calculated that the labourer’s cost of living increased 15 per cent between 1898 and 1912, while his wages rose only 3 per cent (ibid., 26–7).

46 ibid., 308–9.