9

9

High living

The characteristic feature of the English economy in the period from the Great Exhibition down to the outbreak of the First World War was continuing industrial expansion and increasing wealth for those who owned and controlled the means of production. Agriculture, the most basic and traditional industry, remained highly prosperous until the depression of the 1880s, when foreign competition began to shatter the near-monopoly of food supply which the English farmer had previously enjoyed: thereafter, the territorial aristocracy suffered some reduction in fortune as well as in political influence, though in 1914 they were still the undisputed leaders of social life. Their standard of conduct was the one imitated more or less closely and successfully by the new middle classes, called into increasing wealth and power by the growth of industry, commerce, and the professions. At the upper end of financiers, bankers, and railway directors they merged into, and not infrequently inter-married with, the landowning aristocracy: at the lower end of small shopkeepers and clerks they were scarcely distinguishable from the ranks of the skilled worker. For our purpose, however, they all had one thing in common which distinguished them from the working classes: an income which provided some margin over necessary expenditure and therefore permitted a choice in the selection of food.

Much of this margin, in both the middle classes and the aristocracy, was devoted to ‘conspicuous expenditure’ on things which would demonstrate the status of the owner. A large house, costly furniture and tableware were as much a sign of the husband’s success in business as were the elaborate dresses of his wife and daughters: so, too, the employment of domestic servants on a lavish scale both relieved the housewife of unladylike drudgery and announced the prosperity of the establishment which could afford to employ ceremonial butlers, footmen, and coachmen as well as maids and kitchen staff. But it was at meal-times, and especially at the dinner-party, that wealth and refinement could be displayed most effectively. The dinner-party of the Victorian upper classes developed into a unique institution which had the great merit of combining business with pleasure: here the head of the family could entertain business associates and talk ‘shop’ after the ladies had retired to the drawing-room to discuss fashion and arrange matches. Above all, the dinner-party provided a magnificent opportunity to show off the material possessions of the host – the solid furniture, ornate silver tableware and cutlery – and to demonstrate his good taste in the selection of expensive wines and food dressed according to fashionable haute cuisine. Traditional English dishes were now out of favour: to be smart, the menu had to be French and recherche. The acquisition of a French chef, or at the very least of a cook ‘professed’ in French practice, was now essential for the family with serious social aspirations.1

Adjustment to the new régime was not immediate or complete. Away from the influence of the towns, farmers small and large continued to eat, as they had for centuries, three hearty meals a day at breakfast, dinner, and supper: locally grown meat and vegetables, undisguised by fancy sauces, were good enough for them, though their daughters might acquire a taste for frivolous concoctions at the ‘great house’ or hunt balls. Even among some of the urban middle and professional classes, an older pattern of eating sometimes survived late in the century. Writing of these classes in 1886 a ‘foreign resident’ observed:

Their hospitalities are of the solid rather than the advertising kind; their dinners, especially on Sunday afternoons, are Gargantuan repasts at which the table groans with good things. This is particularly the case with that peculiar festivity called ‘high tea’ – a meal still popular with the older members of the class – an informal, to many minds uncomfortable – medley of good things something like a picnic indoors – teacups and wine-glasses side by side, hot dishes and cold, the service intermittent and greatly dependent on self-help. Yet among the newer generation, the strict observance of modern society’s rules gains ground. The evening meal is dinner à la Russe – evening dress derigueur, champagne the favourite wine, and cigarettes are smoked as unfailingly as at Marlborough House. Here too, balls, theatricals, musical evenings follow precisely the lines chronicled in The Morning Post. Costumes seen are as good, probably better: for the wives and daughters of the London bourgeois aspire to dress in the fashion, although their success is not invariably pre-eminently great.2

The writer’s observation of the changing pattern was perceptive. The 1880s and 1890s were a crucial period in the development of middle-class attitudes and standards, and by the time Queen Victoria vacated the throne social imitation had largely imposed the newer pattern of dietary behaviour.

In a monarchical age it was natural that the standard should be set in the royal court. Though Queen Victoria was herself uninterested in food and liked only plain meals, her position as titular head of a vast Empire demanded that her dinner table should be at least as magnificent as that of any in Europe. It was, indeed, typical of her concept of Britain’s imperial role that on every day of the year curry was prepared by Indian servants in the royal kitchens in case it should be asked for by visiting Orientals: usually it was sent back untouched. When the Queen was in residence at Windsor there was an indoor staff of over three hundred servants and a kitchen staff of forty-five, presided over, in the closing years of her reign, by the Royal Chef, M. Ménager. He received what was considered the princely salary of £400 a year, plus £100 a year living-out allowance: when in London, he lived in his own house, not with the other servants in the palace, and arrived each morning by hansom cab. His duty, and that of the eighteen chefs under him, was to prepare the usual meals of breakfast, luncheon, and dinner each day for the Royal Family and their guests – five courses for breakfast, ten to twelve courses for luncheon, and the same for dinner. By any other standard these meals were banquets, but for specially important occasions like the Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 1897, twenty-four extra French chefs were brought in since each of the fourteen elaborate courses required several days to prepare. Breakfast at court was still of the solid, traditional kind. The Queen herself usually had only a boiled egg, served in a gold egg-cup with a gold spoon, but the other members of the family ate heartily – a typical meal was an egg dish such as œuf en cocotte, bacon, grilled trout or turbot, cutlets, chops or steak and, to end, a serving of roast woodcock, snipe, or chicken. Dinner at Buckingham Palace lasted an hour-and-a-half, divided into two by the service of sorbets (water-ices flavoured with port, brandy, or rum) to cool and refresh the palate before the really solid part of the meal – the roast – was tackled. A typical dinner would consist of consommé and thick soup, salmon, cutlets of chicken, saddle of lamb, roast pigeons, green salad, asparagus in white sauce, Macédoine en champagne, mousse of ham, and lemon ice-cream: there would also be on the side-table hot and cold fowls, tongue, beef, and salad. With a luncheon of similar proportions, the Royal Family were adequately, if not excessively, nourished. Even on board the royal yacht Victoria and Albert the usual nine-or ten-course meals were served daily, though on some of the trips few of the party exhibited much appetite.3

Her Majesty’s Dinner

Thursday, 28 June

POTAGES

Consommé tortue Potage des Rois POISSONS

Saumon sauce roche Eperlans frits sauce ravigotte Ris de veau à la Serin

Chaud-froid de volaille à la Reine

RELEVÉS

Boeuf braisé à la Richelieu

Selle d’agneau sauce menthe Petits pois à I’Anglaise RÔT

Cailles aux pommes de terre à Hndienne

ENTREMETS

Asperges sauce Hollandaise

Babas au caraçao Éclairs aux fraises Croûtes de Chantilly

GLACES

Créme au chocolat Eau de citron BUFFET

Hot and Cold Fowls Tongue Cold Roast Beef

Towards the end of the Queen’s reign the length of the dinner-session was somewhat abbreviated due, according to one account, to the Prince of Wales’s haste to reach the cigar stage.4 But Edward VII came to the throne with a reputation as an epicure, and is given credit for the invention of numerous dishes; in his reign the luncheon and supper party, as well as that peculiarly English institution, the week-end, became the vogue, and a craze developed for rare and out-of-season foods. Writing in 1909, Lady St Helier describes ‘plover’s eggs at 2s 6d apiece, forced strawberries, early asparagus, petits poussins and the various dishes which are now considered almost a necessity by anyone aspiring to give a good dinner’. The new king and his queen, Alexandra, were, according to Gabriel Tschumi, who had first-hand knowledge of the royal kitchens during the reign, determined that the meals served at Buckingham Palace should be the best in the world. For the Coronation Banquet of 1902 – which had to be postponed because of the king’s illness – fourteen memorable courses were prepared which included huge quantities of sturgeon, foie gras, caviare, and asparagus: other orders were for 2,500 plump quails, 300 legs of mutton, and 80 chickens. One of the desert dishes, Caisses de fraises Miramare – an elaborate strawberry dish – took three days to prepare. Much of the food which could not be preserved was ultimately distributed by the Sisters of the Poor to needy families in Whitechapel and the East End: their appreciation of such unaccustomed delicacies is not recorded. The amount of waste from such occasions, and from the kitchens of the wealthy generally, was so prodigious that General Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, set up Household Salvage Brigades to collect and distribute it to the poor. Baroness Burdett-Coutts started one such in Westminster, Lady Wolseley another in Mayfair:

Sometimes legs of mutton from which only one or two slices had been cut were thrown into the tub.… It is by no means an excessive estimate to assume that the waste out of the kitchens of the West End would provide a sufficient sustenance for all the Out-of-Work who will be employed in our labour sheds.5

When in good health, Edward VII liked to begin the day with a substantial breakfast – haddock, poached eggs, bacon, chicken, and woodcock before setting out for a day’s shooting or racing. When in residence, there would be the usual twelve-course luncheons and dinners, but Edward liked to get out a good deal to Ascot and Goodwood, and to Covent Garden. On these occasions hampers prepared in the royal kitchens followed him. At Covent Garden, for example, the king took supper in the interval from 8.30 p.m. to 9.30 p.m. served in a room at the back of the royal box: six footmen went down in the afternoon with cloths, silver and gold plate, and a dozen hampers of food followed later. For supper there were nine or ten courses, all served cold – cold consommé, lobster mayonnaise, cold trout, duck, lamb cutlets, plovers’ eggs, chicken, tongue and ham jelly, mixed sandwiches, three or four desserts made from strawberries and fresh fruit, ending with French patisserie. A typical daily dinner menu at Buckingham Palace illustrates the luxury and plenty which was maintained in the Edwardian court.

MENU OF HIS MAJESTY KING EDWARD VII’S COURT

| Buckingham Palace | |

| Turtle Punch | Tortue claire |

| Madeira, 1816 | Consommé froid |

| Johannesburg, 1868 | Blanchailles au Naturel et à la Diable |

| Filets de Truite froids à la Noruégienne | |

| Magnums Moet et | Ailerons de Volaille à la Diplomate |

Chandon,1884 |

Chaufroix de Cailles à la Russe |

| Chambertin, 1875 | Hanche de Venaison de Sandringham, Sauce Aigre doux |

| Selle d’Agneau froide à l’Andalouse | |

| Still Sillery, 1865 | Ortolans sur Canapés |

| Salade à la Bagration | |

| Château Latour, 1875 | Asperges d’Argenteuil, Sauce Mousseline |

| Pêches a la Reine Alexandra | |

| Pâtisserie Parisienne | |

| Cassolettes à la Jockey Club | |

| Brouettes de Glacés assortie | |

| Gradins de Gaufrettes |

Royal White Port

Sherry, Geo. IV

Château Margaux, 1871

Brandy, 1800

4 Juin 1902

Some reduction in the extravagance of menus took place after the accession of George V in 1911. His Coronation Banquet of fourteen courses was, in fact, the last of the great traditional banquets to be served at Buckingham Palace: after the First World War, President Wilson was only honoured with ten courses.

In the highest social circles of the aristocracy and leisured classes the pattern of eating habits followed closely that of the royal example. At banquets, supper balls, and dinner-parties lavish meals on French lines were invariably provided, and the development of rapid transport facilities and of the new techniques of canning and refrigeration brought an ever greater variety to the tables of the rich. Public functions tended to serve more traditional English fare – a Lord Mayor’s Banquet at the end of the last century, for example, consisted of turtle soup, fillets of turbot Dugléré, mousses of lobster cardinal, sweetbread and truffles, baron of beef, salads, partridges, mutton cutlets royale, smoked tongue, orange jelly, Italian and strawberry creams, Maids of Honour, pâtisserie Princesse, and meringues: to this were drunk sherry, punch, hock, champagne, moselle, claret, port, and liqueurs. At a total cost of £2,000, the meal worked out at approximately £2 2s a head.6 The ball supper, a favourite Victorian and Edwardian institution, gave more scope for originality. At one of the most fashionable of the Season, the Caledonian Ball given at the Hotel Cecil, more than 2,000 guests were served with an elaborate menu; even at this, the largest hotel in Europe, it was not always possible to cater for all the guests at one sitting.

Mrs Beeton’s famous manual of domestic economy, written first in article form and published as a book in 1861, considered that for a private ball and supper for sixty persons there should be not less than sixty-two dishes on the table, as well as three épergnes of fruit, ices, wafers, wine, liqueurs, Punch à la Romaine, coffee, and tea. For a sit-down supper at the end of the century, the following was recommended (menu translated):7

BALL SUPPER MENU

Rich consommé in cups

Fried fillets of sole and tartar sauce

Cold salmon

Lobster mayonnaise

Chatouillard potatoes

Truffled partridge pie

Ham and foie gras mousse

Cold lamb and fillet of beef

York ham

Ox tongue

Chicken galantine in aspic

Dressed quails and larks

Russian salad

Pears Melba

Chocolate Savarois

Coffee éclairs

Charlotte with whipped cream

Stewed fruit

Neopolitan ice

Wafers and friandises

Coffee and liqueurs

Such a menu would be served between 12 and 2 a.m., after which the guests might feel sufficiently refreshed to resume the waltz and the polka. Next morning the fortunate young man might find himself faced by a shooting-party luncheon, a typical menu for which included fillets of sole and iced lobster soufflé, braised beef with savoury jelly and dressed oxtongues, fillets of duckling with goose-liver farce, braised stuffed quails, roast pheasant, Japanese salad, and the usual cheeses and desserts.8 Such pleasures were not, of course, for men only, a fact made clear by the letter of a young lady who visited much at country houses in the 1890s:

There was a big shoot yesterday, all of us very tweedy and thick booty, and we lunched in a barn near one of the farms. Such a set out: tables and folding chairs and flowers and fruit, liqueurs and coffee and all sorts of drinks. There were hot dishes too – hot-pot and beefsteak pudding and lots of cold things and puddings and cake.9

The most frequent and typical gastronomic occasion was, however, the dinner-party, which developed in the Victorian period into a highly formalized ritual. At the time Mrs Beeton was writing, fancy name cards had just been introduced. Guests were expected to arrive about half an hour before dinner, during which time the circulation of photograph or crest albums – not, of course, cocktails – helped to pass away the time. According to Richard Dana, a wealthy American who visited England in the 1870s and frequently dined with the aristocracy, one was invited for eight o’clock or even eight-thirty, ‘and you are always expected to be punctually late to the extent of exactly quarter of an hour’. In the 1860s and 1870s the dinner service was still à la française – that is, served in two or three parts with different services. Before it was announced to the host and hostess that ‘Dinner is served’, the soup was already in the plate of each guest: when these plates had been removed, two or three kinds of fish and of meat with the accompanying vegetables and sauces were placed on the table. Altogether, this made up the ‘first service’; all the dishes so far served were, in fact, in Carême’s strict use of the term, entrées, although they might include very substantial ‘made dishes’. Their purpose was to lead up to and prepare the appetite for the roast. This contradicted Brillat-Savarin’s dictum that the progression of dishes at dinner should be from the more substantial to those of a light and delicate nature, but this was not the practice at any rate in England. After the first service, the servants removed the plates and dishes and brought in the second service of three or four different roasts with their appropriate vegetables, gravies, sauces, and salads. The host usually carved and helped the guests himself, aided by his servants: the art of carving was therefore regarded as an important accomplishment. After this, the third course was brought on, consisting of various hot sweets such as flans, puddings, tarts, pies, and different kinds of dry or fresh fruit, cheeses, compotes, bon-bons, and so on. Since all this was put on the table at the same time, little room was left for floral decorations, and usually the only ornament was a massive silver centre-piece or épergne.

This was the classical dinner-menu which had emerged in France in the late eighteenth century, and survived in England until the 1870s and 1880s. One of Mrs Beeton’s menus of 1861 is a typical example of it, though here the second and third courses have been combined:

Dinner of Twelve Persons

FIRST COURSE

Soupe à la Reine Julienne Soup Turbot and lobster sauce Slices of salmon à la Genevese ENTRÉES

Croquettes of Leveret Fricandeau de Veau Vol-au-vent Stewed mushrooms SECOND COURSE

Forequarter of Lamb Guinea Fowls Charlotte à la Parisienne Orange Jelly Meringues Ratafia Ice Pudding Lobster salad Sea kale Dessert and Ices

The traditional dinner underwent major modification in the later part of the century when service à la Russe was introduced, though the French service survived in old-fashioned households throughout the period. Service à la Russe was probably brought to England in the 1850s, but was by no means common until the 1870s and 1880s. The essential difference was that instead of being served in two or three great courses, each placed at the same time before the diners, the dishes were now placed in turn on the sideboard and served to guests by the waiters. The change made the menu more flexible: it resulted in reducing the number of dishes served, and shortened the function by accelerating the service. ‘No dinner’, declared Lady Jeune, ‘should last more than an hour and a quarter if properly served. … Instead of this, dinners are constantly two hours long.’10 The new style was clearly in accord with the age of speed and progress, and, moreover, it had the great advantage that dishes could be served direct from the kitchen while they were hot and palatable without the necessity of long delays unavoidable with the older method. This gave more scope to the skill of the chef, particularly in serving the elaborate hot entrées which, to a considerable extent, became the test of excellence in the Edwardian dinner.

A full dinner of the new pattern therefore consisted of the following courses: (1) hors d’œuvre variés (or oysters or caviare); (2) two soups (one thick and one clear); (3) two kinds of fish (one large boiled, the other small fried); (4) an entrée; (5) the joint, or pièce de résistance; (6) the sorbet; (7) the roast and salad; (8) a dish of vegetables; (9) a hot sweet; (10) ice-cream and wafers; (11) dessert (fresh and dry fruits); and (12) coffee and liqueurs.11 Some of these courses might be omitted or combined, so that a typical menu of the new type would read as follows:12

SOUPS

Consommé Desclignac Bisque of Oysters FISH

Whitebait; Natural and Devilled Fillets of Salmon à la Belle-Ile ENTREÉS

Escalopes of Sweetbread à la Marne

Cutlets of Pigeons à la Due de Cambridge

RELEVÉS

Saddle of Mutton Poularde à la Crème Roast

Quails with Watercress

ENTREMETS

Peas à la Française

Baba with Fruits Vanilla Mousse Croûtes à la Frangaise

Here, the hors d’œuvre course is omitted because it was not yet generally given on the bills of fare of private houses. The idea of eating tasty trifles as a ‘whet’ or appetizer seems to have started in Russia, where guests took caviare, salt herring, anchovies, and other highly flavoured articles, followed by kümmel or brandy, in an anteroom before the announcement of dinner. Some English houses also served what was called an hors d’oeuvre in the mid-century – at Lord Palmerston’s banquets it came after the fish and at the Duchess of Sutherland’s after the remove: in these cases, however, it took the form of ‘pig’s feet truffled’, ‘oyster patties’, ‘timbales’, and ‘croquettes’, which were, properly, entrées. The hors d’œuvre in its subsequent (and present-day) form of sardines, anchovies, salamis, radishes, olives, smoked salmon, smoked ham, canapés, and so on was first introduced by hotels and restaurants towards the end of the century as a convenient way of amusing the customer while his dinner was being prepared: because of its popularity here it was adopted in private households and became usual in Edwardian times. Caviare, served very cold, either in the jar or in a silver timbale, or oysters served with brown bread and butter, lemon, mignonette (crushed cornpepper), and horseradish powder were the usual alternatives. Iced melon, served with castor sugar and powdered ginger, had also appeared before 1914. With the hors d’ œuvre or oysters Chablis was served. After plates had been cleared, two soups, one thick and one clear, were offered by the waiters, and sherry served by the wine butler. When the fish course included a whole salmon or turbot as well as the fried whitebait, smelts or soles, the dish was first presented to the host with the cover raised at his left side. Entrées, consisting of jointed braised fowls, salmis of game, quails or anything of the kind requiring no carving, were then served in the dish as sent from the kitchen, followed by the joint which was carved on the réchaud and served with two or three green vegetables and potatoes. Immediately after this the sorbets appeared and, after them, a large box of Russian cigarettes would be passed round by the butler, followed by a waiter with a lighted spirit lamp or candle. After a few minutes’ pause, the roast of poultry or game accompanied by salad served individually on halfmoon plates was presented; with all these dishes champagne had become the fashionable drink by the end of the century. Finally, the puddings, ices, and savouries, served with fine Bordeaux and old port, the dessert, and, to conclude, coffee and liqueurs. In private houses these were generally not taken at the dinner-table:

When the dessert is over, the hostess either nods or smiles at the lady at the right of her husband and rises; the rest of the ladies do the same and follow her to the drawing-room, where they are rejoined by the gentlemen half an hour later. During this half-hour or so, the gentlemen remain in the dining-room; they draw close to the host and finish their wine, or drink coffee and smoke while one of them, perhaps, tells an after-dinner short story.13

In the two or three decades immediately before the outbreak of war other changes were taking place in the dinner of fashion which still further reduced elaboration and tended to make the meal lighter and more interesting. Lady Jeune, a well-known society hostess but also a ‘modern woman’ in revolt against extravagance and out-dated customs, believed that: ‘No dinner should consist of more than eight dishes: soup, fish, entrée, joint, game, sweet, hors d’œuvre and perhaps an ice; but each dish should be perfect of its kind.’14 Even this represented some reduction of the ten or twelve dishes of the traditional dinner. Equally important, the excessive meat-eating of earlier generations was gradually being replaced by dishes of a more vegetation nature, partly, at least, as a result of the new knowledge of nutrition which emphasized the dietary importance of fresh fruit and vegetables. London had several vegetarian restaurants at the turn of the century, and it is noticeable that the later editions of standard cookery books devoted increasing space to the preparation and service of vegetable dishes.15 Kenney-Herbert urged that the importance placed in English menus on the joint and the rôt should be relegated, and, indeed, that the whole formal pattern of meals and the use of menu-cards should be abolished.16 It was also in line with the new ideas of originality and variety in food that great importance was now attached to the entrée course, which gave great scope to the cook’s talent in preparing and decorating ‘made dishes’. ‘Entrées’, wrote Herman Senn in 1907, ’are generally looked upon as the most essential part of a dinner.… There may be dinners without Hors d’oeuvre, even without Soup, and without a Remove or Relevé, but there can be no well-balanced dinner without an Entrée course.‘17 His book gave a remarkable collection of more than three hundred dishes, divided between vegetable entrées, fish entrées, entrées of veal, beef, mutton, poultry (the largest category), and game, the essence of which was that they were all composed of more than one ingredient (as distinct from solid meats with a garnish) and were served in decorated shapes and moulds. They included such tempting items as Huîtres au Jambon Dubarry, Timbales de Turbot Frascat, Chartreuse de Veau à la Crécy, Entrecôtes Grillées Édouard VII, Soufflé de Volaille à la Hollandaise and Escalopes de Venaison à la Polonaise.

In late Victorian and particularly in Edwardian times, dining out in public at hotels and restaurants became a new and fashionable entertainment of the upper classes. Formerly only men had eaten at their clubs and chop houses: for society women to eat in public was partly a result of their growing emancipation and a desire for conspicuous expenditure, partly a result of the building of magnificent new hotels of the highest standards of elegance and comfort which was taking place from midcentury onwards. One of the first was the Wellington, in Piccadilly, opened in 1853 with a lavishly decorated dining-room for two hundred guests, and two kitchens, one serving English, the other French dishes. Here, luncheon was still a simple, traditional meal, obviously intended for men in town on business or pleasure – a soup, followed by mutton chops, rump steak or cold joint with potatoes and pickles. The social occasion was the dinner, served from four o’clock until nine o’clock – either an English meal of five courses at 3s or French menus of six and seven courses at 5s or 8s.18 But the great age of fashionable dining-out properly dates from the foundation of the Savoy Hotel by Richard D’Oyly Carte in 1889, where the connection with theatre-going was made explicit by after-theatre suppers served from 11 p.m. until 12.30 a.m. Music while dining, which opened with Johann Strauss’s famous orchestra, was another innovation, but the great attractions were the lavish decor and outstanding cuisine, presided over by César Ritz as General Manager and Escoffier as Chef. In 1897 these two left for the new Carlton Hotel: in 1898 Claridges was rebuilt, also by the D’Oyly Carte Company, to be followed shortly by the Berkeley.19

The fabulous cuisine of a hotel like the Carlton could attract the Prince of Wales to its public rooms, and the clientele normally included a few European princes and princesses, ambassadors, a score or more of marquis and marquises, as well as the best-known authors, dramatists, and actresses of the day. Nor was it prohibitively expensive to eat the best dinner in the world among such company. Colonel Newnham-Davis, who wrote a series of articles at the end of the century for the Pall Mall Gazette, which was an early Good Food Guide to London hotels and restaurants, describes the occasion when he took the Princess Lointaine to dinner at the Carlton. He had first consulted with the chef in the morning, and the meal was to their order:

Royal Natives

Consommé Marie Stuart

Filets de Sole Carlton

Noisettes de Chevreuil Diane

Suprême de Volaille au Paprika

Ortolans aux Raisins

Pall Mall Salade

Soufflés aux Pèches à l’Orientate

Friandises

Bénédictines roses

All the dishes were, of course, elaborately dressed – the soup contained eggs and chopped truffles, the soles were served with vermicelli and crayfish tails with a flavour of champagne and parmesan, the suprême de volaille, a cold entrée, was served on a socle of clear ice, and so on. The bill was as follows: ‘Couverts Is; natives 5s; soup 2s; filet de sole 4s; noisettes 4s; suprême de volaille 6s; ortolans 10s (four were served, though only two eaten); salade 1s 6d; péches 4s; café 1s; champagne (Pommery Greno. 1889) £1 1s. Total: £2 19s 6d.’20 In contrast with this, Newnham-Davis describes an excellent dinner at the Comedy Restaurant, Panton Street, where for only 2s 6d he had:

Hors d’oeuvre variés

Consommé Caroline Crème à la Reine Sole Colbert

Filet Mignon Chasseur

Lasagne al Sugo Bécassine Rôtie Salade de Saison

Glace au Chocolat

Dessert

To find snipe on the menu of a half-crown dinner, even in 1901, was somewhat rare. But at the Restaurant Lyonnais in Soho an eatable meal could be had for as little as 8d: ‘Soupe, 1 viande, 2 légumes, dessert, café, pain à discretion.’ At the Hotel Russell the excellent table d’hôte dinner cost 5s; at the Café Royal an à la carte meal for two, cooked by Oddenino, which included caviare, foie gras, quails, champagne, and liqueurs, cost £2 4s 6d. Famous Italian restaurants like Gatti’s and Romano’s were still modest in price, while for a traditional English fish dinner at Simpson’s one could begin with turbot, pass on to fried sole, then salmon or whitebait with cheese and celery to finish for 8s 6d for three persons; two good bottles of Liebfraumilch cost 12s. Still more traditional, the Cheshire Cheese offered its famous pudding of lark, kidney, oyster, and steak at 2s (helpings unlimited), stewed cheese at 4d, and a pint of the best bitter beer, 5d.

Eating out of doors also became a favourite occupation of Victorian and Edwardian society. The cult of the picnic‘, as Georgina Battiscombe points out, ‘springs directly from the Romantic Movement,’21 and it was natural enough that these romantic generations should take delight in organized expeditions into the countryside, especially if the picnic spot could be a ruined castle or abbey to be sketched and explored. Picnicking played a large part in Victorian literature, from Dickens to Surtees, Trollope to Jerome K. Jerome, and, from the amount of space devoted to it in recipe books, in actual life. The food provision on such occasions was lavish. In Mrs Beeton’s first edition of 1861 a ‘Bill of Fare for a Picnic for Forty Persons’ includes:

A joint of cold roast beef, a joint of cold boiled beef, 2 ribs of lamb, 2 shoulders of lamb, 4 roast fowls, 2 roast ducks, 1 ham, 6 medium sized lobsters, 1 piece of collared calves head, 18 lettuces, 6 baskets of salad, 6 cucumbers, stewed fruit well sweetened and put into glass bottles well corked, 3 or 4 dozen plain pastry biscuits to eat with the stewed fruit, 2 dozen fruit turnovers, 4 dozen cheese cakes, 2 cold cabinet puddings in moulds, a few jam puffs, 1 large cold Christmas pudding (this must be good), a few baskets of fresh fruit, 3 dozen plain biscuits, a piece of cheese, 6 lb of butter (this, of course includes the butter for tea), 4 quartern loaves of household bread, 3 dozen rolls, 6 loaves of tin bread (for tea), 2 plain plum cakes, 2 pound cakes, 2 sponge cakes, a tin of mixed biscuits, ½ lb of tea. Coffee is not suitable for a picnic, being difficult to make.

The list ends with:

Beverages: 3 dozen quart bottles of ale, packed in hampers, ginger beer, sodawater, and lemonade, of each 2 dozen bottles, 6 bottles of sherry, 6 bottles of claret, champagne at discretion, and any other light wine that may be preferred, and 2 bottles of brandy.22

These quantities worked out at 122 bottles to be drunk by forty persons, plus an unspecified amount of champagne and light wine.

Later editions of Mrs Beeton, it is true, somewhat reduced these quantities. In 1906 a suitable menu for ten picnickers is given as:

5 lb cold salmon (price 8s 9d), 2 cucumbers, mayonnaise sauce, 1 quarter of lamb, mint sauce, 8 lb pickled brisket of beef, 1 tongue, 1 galantine of veal, 1 chicken pie, salad and dressing, 2 fruit tarts, cream, 2 dozen cheese-cakes, 2 creams, 2 jellies, 4 loaves of bread, 2 lb biscuits, 1 ½ lb cheese, ½ lb butter, 6 lb strawberries.

The total cost was £3 l1s 1d.

The organization required for such excursions was considerable: in Chambers Journal for June 1857, the advice was given that:

A picnic should be composed principally of young men and young women; but two or three old male folks may be admitted, if very good-humoured; a few pleasant children; and one – only one – dear old lady; to her let the whole commissariat department be entrusted by the entire assembly beforehand; and give her the utmost powers of a dictatress, for so shall nothing we want be left at home. … Who else could have so piled tart upon tart without a crack or a cranny for the rich red juice to well through? Who else has the art of preserving Devonshire cream in a can? Observe her little bottle of cayenne pepper! Bless her dear old heart! She has forgotten nothing.

The food on such occasions was all-important, the venue of the picnic secondary. When the British Association held its meeting at Exeter in August 1869, an archaeological expedition was arranged for the members with the object of opening a barrow:

So large a slice of the afternoon, however, was consumed at the splendid collation in the tent near the six-mile stone, together with many other slices of a variety of good things, that there was no time left to complete the examination of the barrow or even to open the kistvaen.… It was intended to open the kistvaen in the presence of the visitors, but they did not visit the spot.23

The food of the professional and middle classes followed a similar pattern to that of the wealthy, suitably modified by the income of the household and the number of domestic servants kept. Dinner parties for them were a good deal less frequent – one a month was a common interval – and the daily fare was a good deal plainer than that previously described, but the kinds of dishes, the order of courses and service, were based on the model set from above, and approached more or less closely as means permitted. For present purposes we may define the middle classes of the later nineteenth century as those with incomes between £160 a year – the point at which income tax was payable – and around £1,000 a year; they and their dependants numbered about 15 per cent of the population at the end of the period. They were among the chief beneficiaries of Britain’s increasing wealth, industrialization, and international trade. Although meat and dairy prices rose sharply in the 1860s during the cattle plague, the subsequent effects of free trade were greatly to reduce the costs of basic foods and to make more and more imported luxuries available to the class.

The result was probably not that the middle classes spent less of their incomes on food than formerly, but that they ate more luxuriously and were prepared to devote increasing amounts of money to enhance their style of living. Comparing life in 1875 with twenty-five years earlier, the author of ‘Life at high pressure’ summed up the change by saying, ‘Locomotion is cheaper, but every middle-class family travels far more than formerly. Wine and tea cost less, but we habitually consume more of each.’24 Social imitation, and what J.A. Banks has called ‘the paraphernalia of gentility’; required a display of houses, servants, dress, and food which inflicted a growing burden on the resources of a class whose expansion was chiefly from the lower end. Near the bottom of the pile, with an income of only £250 a year, J.H. Walsh estimated that food and drink took £116 or 46.4 per cent (meat £30, drink £18): at £500 a year they needed £148 or 29.6 per cent (meat, £40, wine, beer, and spirits £27), while with an income of £1,000 a year food and drink took only £272 or 27.2 per cent (meat £75, drink £70).25 The trend was clear – as income rose, the proportion going to food and drink declined, despite the use of more costly items and despite a larger household of domestic servants to be maintained.

Some ambivalence is discernible in the Victorian middle-class attitude to food. At the beginning of the period the accepted recipe book for those of moderate means was Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery (first edition, 1845),the accent of which was on the importance of economy in contrast to the enormous waste of many English households:

It may safely be averred that good cookery is the best and truest economy, turning to full account every wholesome article of food, and converting into palatable meals what the ignorant either render uneatable or throw away in disdain. … It is of the utmost consequence that the food which is served at the more simply supplied tables of the middle classes should all be well and skilfully prepared, particularly as it is from these classes that the men principally emanate to whose indefatigable industry, high intelligence and active genius we are mainly indebted for our advancement in science, in art, in literature and in general civilization.26

But despite the assurance that the book would concentrate on ‘plain English dishes’, many of the recipes required ingredients and skill which would place them beyond the reach of all but a tiny minority. Truffles boiled in half a bottle of champagne, a ‘common English game pie’ of venison and hare, and soles stewed in cream were expensive delicacies even in mid-Victorian England, scarcely economical by modern standards.

Mrs Beeton’s famous work, which appeared a few years later and remained the accepted culinary compendium throughout the period, also suffered from the same ambivalence. It was, of course, far more than a mere cookery book – a manual of household economy for the domestic entrepreneur, as one writer has described it, containing much information on the management and duties of servants, the equipment of the kitchen, the storage of wine, and so on. Like Miss Acton, Mrs Beeton pleaded for economy in the use of materials while recommending dishes involving dozens of eggs, pounds of butter, and quarts of cream. Writing as she did before the new knowledge of nutrition had developed, it is not surprising that there is a noticeable lack of fresh fruit, vegetables, and salads in her menus, though there is an abundance of meat, fish, and solid foods. Recommended breakfast dishes included grilled steak, game pie, devilled turkey, broiled kidneys, fried soles, and ragout of duck, besides eggs, cold ham, and tongue. For dinner-parties and ball suppers Mrs Beeton’s menus were as lavish as any of the day, but for the ordinary family dinner, such as would be eaten by the professional man on his return from office or counting-house, there were three or four courses: a soup or fish, a joint, vetetables, and pudding.

Plain Family Dinners

Later in the century recipe books appeared which were written more specifically for middle- and lower-middle-class households and gave serious attention to the question of cost. Mary Hooper’s Little Dinners: How to Serve them with Elegance and Economy, was clearly written with the greatest female problem of the day in mind – the scarcity of husbands for middle-class girls:

It cannot be too strongly urged upon the ladies of the middle classes that there never was a time when it was so necessary for girls to be instructed in every branch of domestic economy. We cannot misread the signs of the times, or doubt that unless the men of the next generation can find useful wives, matrimony will become even a greater difficulty for them than it is now. … Let all be sure that she who in these days of expensive living shows how the best use can be made of cheap material, and who in any measure helps to revive what threatens to become a lost art in the home, does a work which far outweighs any within the power of woman.27

By the 1870s the middle classes were expanding rapidly, but while sons went off to administer and missionize the Empire, daughters competed keenly for those who remained; the dinner-party consequently became even more important as a means of matrimonial introduction. Mary Hooper’s book gave complete specifications for a monthly dinnerparty throughout the year which could be provided at modest cost; for example:

JANUARY

Calf’s Tail Soup

Turbot à la Reine Fillet of Beef – Roasted Artichokes Stewed Pheasant Lemon Omelets – Chestnut Cream JUNE Lobster Soup Neck of Lamb à la Jardinière Chicken aux Onions Currant and Raspberry Tart Cheese Fondu OCTOBER Veal Broth Fillets of Cod Caper Sauce Roast Rump Steak Tomato Sauce Braised Partridges Custard Pudding Raspberry Jelly

Mrs J.E. Panton’s From Kitchen to Garret, which appeared in 1888, is interesting as being written for ‘little people’ with incomes of from £300 to £500 a year, and for the full advantage which it took of the cheapened cost of food in recent years:

Dress and house rent are the two items that have risen considerably during the last few years; otherwise, everything is much cheaper and nicer than it used to be before New Zealand meat came to the front, and sugar, tea, cheese, all the thousand and one items one requires in a house, became lower than ever they had been before; and therefore, if she be clever and willing to put her shoulder to the domestic wheel, she can most certainly get along much more comfortably in the way of food than she used to do. For example, when I was married [17 years earlier] sugar was 6d a pound and now it is 2d; and instead of paying Is Id a pound for legs of mutton, I give 7 ½ for New Zealand meat, which is as good as the best English mutton that one can buy. Bread, too, is 5 ½d–and ought to be considerably lower-as against the 8d and 9d of seventeen years ago … and fish and game are also infinitely less expensive, for in the season salmon is no longer a luxury, thanks to Frank Buckland, while prime cod at 4d a pound can hardly be looked upon as a sinful luxury.28

Two pounds, or at most £2 10s a week should keep ‘Angelina, Edwin and the model maid’ in comfort, thought the writer. This was calculated on the basis of meat 12s, bread and flour 4s, eggs 2s, milk 4s,½ lb tea 2s 6d, 1 lb coffee Is 7d, sugar 6d, butter (2 lb) 3s, and the remainder for fruit, fish, chickens, and washing:

Should our bride have a small income of her own, this should be retained for her dress, personal expenses, etc., and should not be put into the common fund, for the man should keep the house and be the bread-winner.

But even on £2 a week for food, the household of three could live comfortably. For breakfast: fruit, preserves, slices cut from a tongue (3s 6d) or nice ham (8s 6d), sardines (6 ½d a box), eggs, fried bacon, curried kidneys, mushrooms, a fresh sole, ‘an occasional sausage’; luncheon for Angelina and the maid might consist of cold beef followed by a lemon pudding, fish, a boiled rabbit, roast pork with apple sauce, and savoury pudding, or a stewed neck of mutton with pancakes to follow: ‘Edwin’s dinner requires, of course, more consideration’ – but there ought always to be soup and fish before the joint, vegetables, puddings, and dessert to follow. On £2 a week for three adults this was good fare which would have been impossible before the 1880s. Occasionally – but only occasionally – a little dinner-party might be given with money saved from the housekeeping, but how expensive even the most carefully planned menu could be for such modest incomes is indicated by the following costing:

White soup (1s)

Soles, Sauce Maître d’Hôtel (3s 6d)

Stuffed Pigeons (three at lOd each, total cost 2s 6d)

Roast Beef, Yorkshire Pudding (6s 6d)

Wild Duck (5s)

Mince Pies (ls 6d)

French Pancakes (8d)

Cauliflower au gratin (8d)

Dessert

(total cost of dinner not including wine, £1 1s 4d)

Other menus included pheasant (2s 6d each), salmon (2s 6d a pound), oysters (Id each), and turkey stuffed with chestnuts (8s).29

At the end of the century Mrs C.S. Peel, in one of her numerous works on housekeeping, estimated that a middle-class family of four or more could live plainly, but sufficiently, on 8s 6d per person per week: ‘nice living’ cost 10s, ‘good living’ 12s 6d, and ‘very good living’ 17s 6d.30 On the evidence of household budgets it seems likely that the proportion of income going to food had risen somewhat since mid-century, despite the substantially lower costs of basic foods. G.S. Layard’s article of 1888 on ‘How to live on £700 a year’ suggested £237 on food for two adults, two children and three servants, or 39 per cent,31 while G. Colmore’s estimate in 1901 for a household of only two adults and two servants with an income of £800 a year gave £299 on food, or 37.4 per cent:32 both were substantially higher proportions than in Walsh’s budgets of 1857. The difficulty is to know whether these ‘ideal’ budgets matched reality. We may test them against the actual experiences of two families.

In the 1880s a retired officer with £800 a year was living on the border of Wales with his wife, five children, four maids, and a gardener. The three nursery children were fed very plainly – for breakfast porridge, bread and milk, fried bread, toast or bread and dripping, sometimes jam; for lunch they joined the adults in hot or cold meat, vegetables, and a pudding, except that on Sundays it was invariably roast beef, Yorkshire pudding, roast potatoes, vegetables, apple-tart in summer and plum pudding in winter. When the children grew older the family moved to Clifton so they could have private, day-school education:

A household reduced to cook and house-parlourmaid, early dinner, high tea at six o’clock in order to save money and service. As I became older, I began to realize the constant planning, contriving and going without which is the lot of people, placed as my parents were placed, who strive to educate five children well and to live in the society of their equals.

Her mother was allowed £5 5s a week for food, cleaning materials, and washing for the household of nine – about 10s each for food:

Oh, the struggle to make it do, the constant anxiety that when the week’s ‘books’ were set before him, more money would have to be demanded of my father. The introduction of quick steamships and cold storage enabled foreign meat to be brought into the English market, and excellent meat it was. The butchers scorned it – naturally – and told terrible tales of its origin to the servants, and frequently sold it as home-killed. The outcry against it became hysterical: our maids behaved as if they had been asked to eat rat poison. ‘We will eat it’, decreed my father, ‘and give English meat to the servants.’ In the end what was good enough for ‘the Captain’ became good enough for them.

About this time, factory-prepared foods, soups and sauces came into greater use: jams, jellies, potted meats, tinned and bottled fruits, also labour-saving foods such as ready-cut lump sugar and ‘castor’ sugar, stoned raisins, pounded almonds, prepared and chopped suet in packets, packet jellies, powdered gelatine, and all sorts of patent cleansers. Fewer and fewer people baked at home, except in the north.33

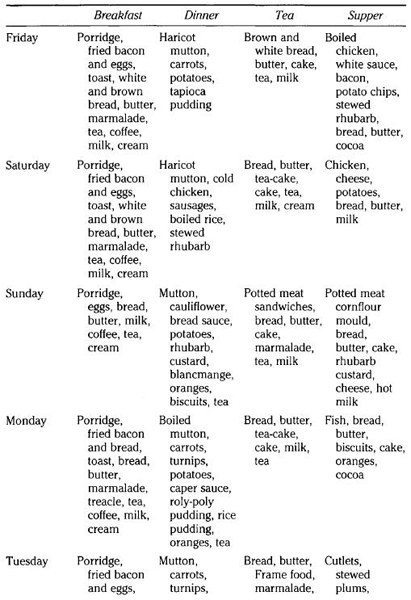

A second actual example is taken from York in 1901. B. Seebohm Rowntree’s famous study of poverty extended as far upwards as ‘Class C – Servant-keeping Class’; these were ‘families who are comfortably off (keeping from one to four servants) but who live simply.… Only one of the [six] families dines in the evening, the male heads of the households are engaged either in professions or in the control of business undertakings.’34 These were the tradesmen and managers, the cashiers and chief clerks who constituted the broad base of the middle classes, lived modestly in suburban villas, had an annual seaside holiday, and educated their children at the local grammar or private school. Case No. 22 is typical. The largish household of five adults and three children consumed £2 10s 6d worth of food a week, and what their meals during the week ending 23 May 1901 consisted of is given in Table 24.

The diet was somewhat heavy and deficient in fresh vegetables, though otherwise not unnutritious; it provided 4,009 kilocalories per man a day, well above the 3,500 required by those in moderate work. The inclusion of relatively recent introductions like brown bread (in fact, Hovis) and ‘Frame food’ is significant; other families in Class C ate ‘Benger’s Food’, potted shrimps, pineapple, sardines, bananas, and stewed prunes. (‘Frame food’ and ‘Benger’s Food’ are patent foods for infants/invalids.)

For the lower middle classes, probably more than for any other section of the community, the cheapness of food in the later nineteenth century had brought greater variety and palatability to the diet. In particular, cheaper meat allowed the Englishman to indulge his liking for a joint, while technology also contributed an important service by bringing tinned fish and fruit out of season to those who could afford to live above

Table 24 Menu of meals of a household of 5 adults and 3 children, income £2 10s 6d in 1901

subsistence level. The work of the housewife in preparing and cooking food had also become lighter – an important consideration as domestic servants were becoming scarcer and more expensive by the end of the century and ‘the servantless house’ was a respectable reality for those towards the lower end of the middle class. It was especially in such households that the new factory-made foods were appreciated, though canned and preserved foods might be scorned in wealthier establishments. Canning, in fact, was no new discovery, dating back at least to the 1820s when Moir and Son began canning lobster, salmon, and trout around Aberdeen; Crosse & Blackwell’s had also established a salmon-canning factory at Cork in 1849, adding this to their thriving trade in pickles (200,000 gallons a year by the 1860s) and catsup (27,000 gallons). Canned Californian peaches, pears and pineapples were common by the 1880s, and by 1914 Britain was the world’s largest importer of tinned foods.35 Other useful innovations included baking powder, invented by Alfred Bird in 1843, who then moved on to eggless custard and blancmange – available by the 1870s in fourteen flavours. Of even greater convenience were the breakfast cereals which began to rival the traditional, but time-consuming, porridge in the 1890s: the American Quaker Oats Company opened a London agency in 1893 and the Canadian Shredded Wheat Company a UK subsidiary around 1908.36 The other great transatlantic food manufacturer, H.J. Heinz, was not yet a household name before the First World War, though his tomato ketchup and other products were sold by Fortnum and Mason from 1886; his baked beans, introduced to the United States in 1895 and piloted in Lancashire and Yorkshire in 1905–6, met ‘no immediate response’.37 English palates remained to be educated to some canned foods, but by 1914 the world food market was so organized as to place the cheapest wheat and meat, the best fish, tea, and coffee on English tables. The complacency with which we accepted this position of dependency was shortly to be rudely shattered.

Notes

1 For an excellent, general account of upper-class Victorian society, see Leonore Davidoff (1973) The Best Circles: Society, Etiquette and the Season.

2 Society in London by a ‘Foreign Resident’ (1886).

3 Full details of the organization of the royal cuisine in the later years of Queen Victoria’s reign are given in Gabriel Tschumi (1954) Royal Chef: Recollections of life in royal households from Queen Victoria to Queen Mary.

4 Hampson, John (1944) The English at Table, 43.

5 Booth, General (1890) In Darkest England, and the Way Out, 118–19.

6 Rey, J. (nd, c. 1914) The Whole Art of Dining, 93.

7 ibid., 107

8 The New Century Cookery Book. Practical Gastronomy and Recherché Cookery (enlarged edn, 1904), 881.

9 Quoted in Mrs C.S. Peel (1929) A Hundred Wonderful Years. Social and Domestic life of a Century, 1820–1920, 113–14.

10 Jeune, Lady (1895) Lesser Questions.

11 Rey, op. cit., 71.

12 Mrs A.B. Marshall’s Cookery Book (revised and enlarged edn, 1879), 474.

13 Rey, op. cit., 80.

14 Lady Jeune, op. cit.

15 Francatelli, Charles Elmé (1911) The Modern Cook, ed. C. Herman Senn.

16 Kenney-Herbert, A. (1894) Common-Sense Cookery for English Households (2nd edn), 22.

17 Senn, C. Herman (1907) Recherchés Entreés. A collection of the latest and most popular dishes, 7.

18 London at Dinner, or Where to Dine (1858, reprint 1969), Advertisements, 2–11.

19 MacKenzie, Compton (1953) The Savoy of London, chaps 2–5.

20 Newnham-Davis, Lieut.-Col. (1901) Dinners and Diners. Where and How to Dine in London, 6–10, 15–17, et seq.

21 Battiscombe, Georgina (1949) English Picnics, 11.

22 Beeton, Isabella (1861) The Book of Household Management (facsimile edn, 1968), 960.

23 Transactions of the Devonshire Association for the Advancement of Science, Literature and Art (1869); quoted in Battiscombe, op. cit., 101.

24 Greg, W.R. (1875) ‘Life at high pressure’, The Contemporary Review (March), 633. Quoted in J.A. Banks (1965) Prosperity and Parenthood, 67, which see generally for a discussion of the middle-class cost of living.

25 Walsh, J.H. (1857) A Manual of Domestic Economy, 606 et seq.

26 Acton, Eliza (1856) Modern Cookery for Private Families, VIII.

27 Hooper, Mary (1878) Little Dinners, How to Serve them with Elegance and Economy (13th edn), XIII-XIV.

28 Panton, J.E. (1888) From Kitchen to Garret: Hints for Young Householders, 19.

29 ibid., 212 et seq.

30 Peel, Mrs C.S. (1902) How to Keep House, 14.

31 Layard, G.S. (1888) ‘How to live on £700 a year’, The Nineteenth Century (February), 243.

32 Colmore, G. (1901) ‘£800 a year’, Cornhill Magazine (June), 797.

33 Quoted in Peel, A Hundred Wonderful Years, op. cit., 143–9.

34 Rowntree, B. Seebohm (1901) Poverty: A Study of Town Life, 251 et seq.

35 Johnston, James P. (1977) A Hundred Years of Eating. Food, Drink and the Daily Diet in Britain since the late Nineteenth Century, 54.

36 Fraser, W. Hamish (1981) The Coming of the Mass Market, 1850–1914, 172–3.

37 Potter, Stephen (1959) The Magic Number: The Story of ‘57’ 56 and 117–18.