5 Political legitimacy and support

As early as the 1960s, Easton's breakthrough study of different political systems claimed that for any political system to survive it has to have a certain degree of support from its population (one of the two input functions described in his application of systems theory to political science).1 Before the 1960s, authoritarian political systems, such as the former Soviet Union, were seen as lacking essential popular political support and legitimacy. Easton's study was later supported by research evidence which showed that popular support for the political regime from sizable societal segments is crucial for the functioning and maintenance of any form of government.2 In general, levels of political support and legitimacy are more readily expressed and measured in democracies than in other forms of political systems. Popular democracy is also believed to be a more durable political system under socio-economic stress.3 Levels of political support and legitimacy are linked to regime stability. In democracies, waning political support for the ruling party or leaders often leads to regime change through an open and fair popular election. Even under authoritarian systems, sufficient popular support can also be an important factor affecting socio-political stability. Serious erosion of political support and legitimacy in authoritarian countries may lead to regime change or even revolution through violence.

Political legitimacy is a relatively new term, even though it connotes a very traditional concept. One of the most often used definitions of legitimacy is offered by Sternberger:

Legitimacy is the foundation of such governmental power as is exercised both with a consciousness on the government's part that it has the right to govern and with some recognition by the governed of that right.4

There are several characteristics of political legitimacy as defined above. First, legitimacy is a subjective concept that involves consciousness and awareness; it is more a matter of belief and mindset than a legal concept.5 Second, legitimacy concerns two parties: the governing and the governed. Neither the governmental claim of legitimacy nor the recognition of that claim on the part of the ruled should be left out of the conceptualization and study of political legitimacy. Third, legitimacy does not require total recognition of governmental legitimacy claims by the governed. Political legitimacy should be viewed as a concept of continuum with varying degrees. A political regime can claim legitimacy so long as certain segments of the population recognize and share the government's claims of legitimacy.6

Studying political support and legitimacy in authoritarian countries such as China is often difficult and tricky. It has long been debated whether communist regimes enjoy any legitimacy. It is a simplistic view to believe that all communist regimes are purely dependent on oppression and coercion and do not have any legitimacy. Sources and levels of legitimacy vary from one authoritarian country to the next. Weber, one of the first scholars to study political legitimacy, identifies three ideal types of legitimacy: traditional, charismatic, and legal-rational. Traditional legitimacy is based on long-held norms, customs, divine power, and right. Charismatic legitimacy rests upon an individual leader's charisma, personality, and character. Legalrational legitimacy depends upon the legality of established and objective rules.7 Not surprisingly, Weber's preferred type of legitimacy is the legalrational type. Many contemporary political scientists are disappointed by Weber's omission of democratic legitimacy.8 He viewed democratic legitimacy as part of the charismatic type of political legitimacy because successful political candidates often have to possess personal appeal and charisma to be elected. Weber's typology of sources of legitimacy is applicable to communist systems such as the People's Republic of China.

The initial sources of legitimacy for the Chinese communist government after 1949 were the successful Chinese Communist Party's revolution and the lofty goals of socialism.9 Unlike the Russian communist revolution, which was primarily a coup that occurred in October 1917, the Chinese communist revolution was a hard-fought struggle that lasted for more than two decades. The success of the Chinese communist revolution was astonishing, considering that the CCP started out with only a few dozen members. It defeated the Nationalists, which had one of the largest armies in the world, despite being supported by the United States. The spectacular success of the Chinese communist revolution provided the CCP with its initial legitimacy because of the traditional Chinese belief that only successful revolts are legitimate revolts. The successful conclusion of the Chinese communist revolution gave the new regime a ‘mandate from heaven’. Moreover, the initial legitimacy of the CCP was further strengthened by the prospective economic and social benefits promised by the socialist system, such as egalitarianism, sufficient provision of food and shelter, free education, affordable medical care, job security, price stability, the liberation of women, social stability (including a low crime rate), and the elimination of social evils (such as corruption, gambling, and prostitution).

Between the 1950s and the early 1970s, Chinese government legitimacy primarily came from relatively successful economic development, ideological intensification, and Chairman Mao Zedong's personal charisma. The CCP did achieve many of the socialist goals mentioned above in the 1950s and the early 1960s. Almost full employment was achieved in the cities, job security was guaranteed, income was by and large equalized, basic human needs were largely satisfied, and social evils were significantly reduced if not totally eliminated. In the 1950s and 1960s Chairman Mao launched several ideological purification campaigns such as the Anti-Rightist movement and the Cultural Revolution. In the meantime, a strong personality cult was built around him, whose status was elevated to a god-like figure in China. Mao was often referred to as the ‘red sun’ and savior of the Chinese nation. Mao's personal charisma became an important source of CCP's legitimacy.

The political discontent created by ten years of Cultural Revolution began to erode the legitimacy of the CCP in the mid-1970s. Much political and social stability was lost during the Cultural Revolution, and for many, political cynicism and bitterness replaced ideological rhetoric and revolutionary fervor. In addition, a lack of economic improvement owing to the incessant political movements also contributed to the deterioration of the CCP's legitimacy. Finally, Mao's death in September 1976, the deaths of Premier Zhou Enlai and Marshal Zhu De in January and July, and a devastating earthquake all in the same year were strong and ominous signs to many Chinese that the CCP was losing its ‘mandate from heaven’, and a new era in Chinese history was about to begin.

To salvage its undermined political legitimacy, the CCP began to shift its legitimacy basis from Mao's ideological and charismatic modes to political and economic rationalization and legalization in a period known as the reform era. The CCP rejected Mao's extreme ideological positions and the Cultural Revolution and made modernization and economic development the central focus of the Party. With regard to Party personnel, the CCP denounced personality cults and adopted a mandated retirement system for all Party officials. In order to improve the efficiency of bureaucratic institutions, professional skills and educational background were emphasized when recruiting Party and government officials, criteria which were ignored in the Maoist era. The improvement and strengthening of socialist legality and due process was another area in which political rationalization was manifested. Economic rationalization involved mainly breaking ideological taboos and respecting objective laws of economics through drastic economic reforms. The main economic reform measures included the decentralization of the economic decision-making process, the introduction of a by-and-large market economy, some degree of privatization, and promotion of foreign trade and investment. Since the late 1970s, the CCP's legitimacy has been built upon a mixture of political and economic rationalization and economic performance – in terms of improving people's living standards.

Measuring rural political support in southern Jiangsu province

The focus of this chapter is to study the levels and sources of popular support among peasants in southern Jiangsu province for the current political system and regime in China. Specifically, the following questions will be answered: ‘To what extent do rural residents in southern Jiangsu province support the current political system in China?’, ‘How do rural residents evaluate governmental policies?’, ‘Who among them tend to be more supportive?’, and ‘What factors affect the level of support among peasants in southern Jiangsu province?’ Even though the findings may not be generalized across all rural areas in China, they may be illustrative and suggestive in understanding rural support for the current political system and the legitimacy of the CCP. The success of the Chinese communist revolution was largely due to the popular support that the CCP received from the Chinese peasantry. Today the majority of the Chinese population is still peasants. Findings from this chapter will help in understanding and predicting the political stability of the PRC.

Popular support for a political regime can be divided into two types of support: instrumental support and diffuse (or affective) support. Instrumental support refers to the public's support and evaluation of governmental performance and specific policies. This kind of support is often formed in a relatively short period of time and is subject to quick change. Diffuse support refers to generalized emotional attachments members of a society have for the government and political system in general. Diffuse support, which takes years to form and is influenced by socialization forces, is more entrenched and provides the firm foundation for the stability and viability of a given political system and regime.10 Diffuse support among southern Jiangsu peasants for the current political system in China is the dependent variable in this chapter.

Many scholars have proposed ways to operationalize the concept of ‘diffuse political support’ or political legitimacy. For Lipset, political legitimacy is tied to the affect for the prevalent political institutions in a society.11 Easton sees diffuse political support as affect for authorities, values, and norms of the regime, and for the political community.12 Combining the two approaches, Muller and Jukam identify three major operational components for the concept of political support or political legitimacy: ‘affect tied to evaluation of how well political institutions conform to a person's sense of what is right;’ ‘affect tied to evaluation of how well the system of government upholds basic political values in which a person believes;’ and ‘affect tied to evaluation of how well the authorities conform to a person's sense of what is right and proper behavior.’13 Following Muller and Jukam's operationalization of political support, I measured popular support for China's political regime among southern Jiangsu rural residents by asking them in the survey to assess the five statements below:

1 I am proud to live under the current socialist system.

2 I feel that my personal values are the same as those advocated by the government.

3 I have an obligation to support the current political system.

4 I very much respect our governmental institutions in China.

5 I believe that in general the courts in China guarantee fair trials.

These five statements are designed to detect the popular affect for the values and norms of the regime, respondent's generalized feeling about political institutions and the current political system, and respondent's evaluation of political authorities in terms of their fairness. Respondents were asked to rate each of the five statements on a four-point scale where ‘1’ indicates the respondents’ strong disagreement with the statement, and ‘4’ indicates their strong agreement with the statement. The respondents were given the option of ‘hard to say’. These five items were then combined to form an additive index to capture a collective profile of a respondent's level of political support or evaluation of regime legitimacy, ranging from 5 (the lowest possible regime support) to 20 (the maximum level of regime support). This index is used as the dependent variable in the multivariate analysis later on.

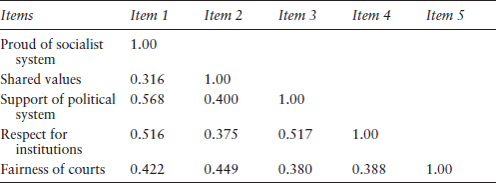

To assess the reliability of this set of items for regime support or legitimacy, I examined the inter-item correlations and reliability coefficients associated with the five items. As Table 5.1 shows, the inter-item correlations range from moderate to strong, with an overall reliability coefficient (alpha) of 0.78. I also performed a principal component analysis of the five items to make sure that they are loaded on one single factor (see Table 5.2). The results from both the inter-item correlations and factor analysis conform to my expectation for this multi-item measure for regime legitimacy and support.

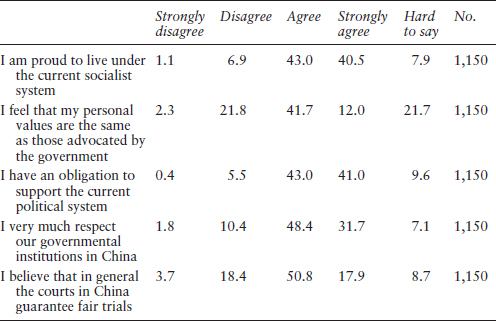

Table 5.3 shows the levels of diffuse political support for the current political regime among peasants in southern Jiangsu province. It appears that the Chinese political system enjoyed moderate to high levels of political support and legitimacy among the southern Jiangsu peasantry. Clearly a majority of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with all five statements that collectively indicated support for the political regime in China. However, there are variations in the answers to these statements. While 84 percent of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statements ‘I am proud to live under the current socialist political system’ and ‘I have an obligation to support the current political system’, a lower number of respondents gave affirmative answers to the other three statements. In fact, only 55 percent of the surveyed felt that their values were the same as those advocated by the Chinese government. The survey results and the patterns of levels of support correspond to findings from a similar survey conducted in Beijing in the mid-1990s and other studies.14

Table 5.1 Inter-item correlations for regime legitimacy items

Reliability coefficient (5 items) alpha=0.78

Table 5.2 Factor (principal component) analysis of regime legitimacy items

Items |

Factor loading |

Proud of socialist system |

0.600 |

Shared values |

0.446 |

Support of political system |

0.619 |

Respect of institutions |

0.583 |

Fairness of courts |

0.494 |

The moderately high level of affective support found in our survey of rural residents in southern Jiangsu province for the political system in China may be explained by the following factors. First, as mentioned earlier, during the reform era the CCP shifted its base of legitimacy from a largely ideological stance to a mostly economic one. Much evidence indicates that this newly claimed base of legitimacy is working in favor of the political regime in China. Southern Jiangsu province is one of the most economically developed areas in China and is highly industrialized. It is reasonable to assume that economically better-off people tend to show more affection for the system they live in. The relationship between economic conditions and a level of political support will be further examined later in this chapter.

Second, the relatively high level of regime legitimacy shown by southern Jiangsu peasants can be explained by Antonio Gramsci's concept of ‘ideological hegemony’. The CCP has ruled China for over six decades and three generations of Chinese grew up in the political system. The Chinese people have always been indoctrinated and socialized since early childhood that ‘only the CCP can save China’ and the fact that the CCP became the ruling party was ‘a historical choice’ (not unlike a ‘mandate from heaven'). These themes have become ideologically hegemonic positions in the mindset of the Chinese people. Indeed, it does not seem that there is any viable alternative political force that can replace the CCP. Capitalizing on the breakup of the former Soviet Union, instabilities in some of the Eastern European countries and developing countries that have experienced regime change, the CCP has driven home the message that China could end up in the same situation without the CCP being the exclusive ruling party. The Chinese government since 1989 has engaged in what I would call ‘negative legitimization’ tactics. Negative legitimization refers to a regime's effort to increase its political legitimacy by painting the alternative as even more undesirable or totally discrediting and delegitimizing the alternative.

Table 5.3 Levels of regime support and legitimacy among southern Jiangsu peasants (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

More explanations for rural political support in southern Jiangsu province

A multivariate analysis will provide a better picture of the factors that might have influenced the levels of political support among peasants in southern Jiangsu province. Specifically, I will look into the following factors: evaluations of government policy performance, the level of political content with local officials, life satisfaction, fear of socio-political chaos, a prospective evaluation of China's economic and political conditions, the level of political interest, and a number of demographic factors.

Evaluations of government policy performance

Evaluation of government policy performance is part of the concept of ‘instrumental support’. According to Easton, ‘specific’ or instrumental support ‘arises out of the satisfaction that members of a system feel they obtain from the perceived outputs and performance of the political authorities’.15 As mentioned earlier, instrumental support, unlike affective support, is formed in a relatively short period of time and is subject to rapid erosion with less impact on the overall political stability and viability of a regime. A number of scholars have studied empirically the relationships between affective support and instrumental support and their impact upon political stability.16 Lipset offers a four-fold typology to explain the relationship between the two types of support and political stability. Specifically, he argues that when both affective support and instrumental support are high, political stability is expected to be strong; when both types of support are low, the political stability of a regime is seriously threatened; when affective support is high while instrumental support is low, the threat to regime stability is small; and when affective support is low and instrumental support is high, the regime remains stable but fragile.17 Affective support and instrumental support are obviously inter-related. It has been found that evaluations of governmental performance and support of political regime are correlated. Studies have suggested that sustained positive evaluations of incumbent policy performance can increase the level of affective support or regime legitimacy.18 That is why, according to Macridis and Burg, many non-democratic regimes survive.19

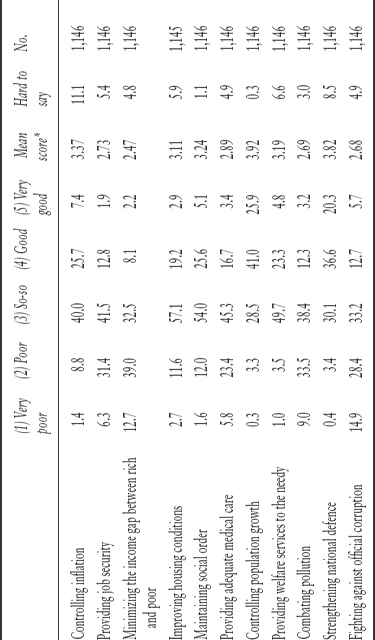

I would argue that this correlative relationship between evaluations of government policy performance and support for political regimes also exists in China. As mentioned earlier, the CCP's basis for legitimacy has shifted from Maoist ideology and personal charisma to economic performance in the reform era. An empirical study of Beijing residents in the mid-1990s found a positive relationship between citizens’ evaluations of government policy performance and regime legitimacy.20 I, therefore, hypothesize that those who gave better evaluations of government policy performance tended to be more supportive of the political regime in China. Respondents in the survey were asked to grade central government policy performance in eleven policy areas:21 controlling inflation, providing job security, minimizing the income gap between rich and poor, improving housing conditions, maintaining social order, providing adequate medical care, controlling population growth, providing social welfare services to the needy, combating pollution, strengthening national defense, and fighting official corruption.

Respondents were asked to grade each of the items based on the grading scheme of ‘1’ to ‘5’ (a commonly used scheme in Chinese schools), where ‘1’ is a fail and ‘5’ stands for excellence. Table 5.4 shows where my survey respondents stood with regard to their evaluation of Chinese central government performance in the eleven different policy areas. Overall, peasants in southern Jiangsu province gave mediocre evaluation or passing grade to Chinese central government performance in most policy areas. In only two policy areas: family planning and national defense, the majority of the respondents rated central government effectiveness as either ‘good’ or ‘very good’. In two policy areas, minimizing the income gap between rich and poor and fighting corruption, the majority of the respondents gave the central government performance a failing grade (either ‘poor’ or ‘very poor'). The findings are not surprising. The Chinese central government has done a better job in protecting the country and in effectively carrying out the ‘one child’ family planning policy. On the other hand, the income gap between the haves and have-nots in China has widened significantly in the reform era. Official corruption is another troubled area that citizens in China often complain about. These findings are also consistent with findings from other surveys conducted in China in recent years.22

Table 5.4 Evaluations of central government policy performance (%)

Note

*Mean scores (between 1 and 5) are not in percentile.

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Level of political content with local officials

Even though China has a highly centralized system, local officials at county, township and village levels play extremely important functions. They are often perceived as ‘parent’ officials (fumoguan) who are supposed to take care of all the needs of the people under their jurisdiction. Local officials at county and township levels and village officials23 are the foot soldiers who carry out central government policies and govern de facto 70 percent of the Chinese population.24 In the eyes of rural residents local officials are representatives of the central government and they are the first port of call for when they need help. A major problem in policy implementation in China is that local authorities tend to distort and selectively carry out policies passed on to them from above.25 Tip O'Neill's26 slogan ‘all politics is local’ is definitely applicable to China. How local officials behave and how they are perceived by local residents naturally affects people's affective support for the entire political system. Therefore, it is important to find out how content rural residents in southern Jiangsu province were with their local officials and how the level of their political content with local officials’ performance impacted their affective support for the political regime in China.

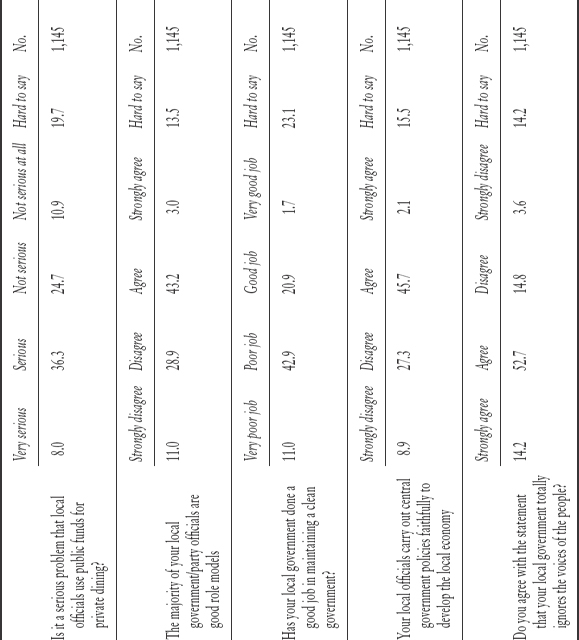

Respondents were asked five questions concerning their local officials’ performance: ‘Is it a serious problem that local officials use public funds for private dining?’, ‘Are the majority of your local officials good role models?’, ‘Has your local government done a good job in maintaining a clean government?’, ‘Do you agree with the statement that your local officials have carried out central government policies faithfully to develop the local economy?’, and ‘Do you agree with the statement that your local government totally ignores the voices of the people?’.

Table 5.5 shows that peasants in southern Jiangsu province were modestly politically content in some areas while discontent in some other areas (the answers range from being politically discontent to politically content). The most positive answer was given to the question of whether local officials were role models. Close to 50 percent of the respondents said ‘yes’ to the question. Close to 50 percent of the respondents also believed that their local officials had carried out central policies faithfully in developing the local economy. However, most of the peasants (51.5 percent) in the survey were not very happy with their local government's effort to maintain a government free of corruption. A higher percentage were unhappy with their local government's anti-corruption efforts than with that of the central government (see Table 5.4). Over 60 percent of the respondents did not believe that their local government paid any attention to their voices and opinions, while only 20 percent believed otherwise. The picture depicted here is not encouraging news for the Chinese government. It should be noted that as rural southern Jiangsu province is one of the most economically developed areas in China the local government there is probably not the most corrupt compared to other rural regions. The level of discontent among peasants in poorer regions could be higher. I hypothesize that peasants who were less content politically with their local government tended to show less affective support for the general political system in China. Answers to these five questions and statements are combined to form an additive index of the level of political content to be used as an independent variable in the multivariate analysis.

Table 5.5 Levels of political content with local officials (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Life satisfaction

The relationship between citizens’ life satisfaction and their support for the political system they live in is well documented in both democracies and authoritarian countries. It is argued that individuals’ positive assessment of their socio-economic conditions contributes to democratic stability in established democracies.27 It was found that life satisfaction also contributed to regime legitimacy and support in authoritarian countries such as the former Soviet Union.28 Similarly, studies have found that significant improvements in living standards and economic conditions in the reform era in recent years led to improved regime legitimacy of the CCP among the Chinese people. After the Tiananmen democracy movement in 1989, the Chinese government conscientiously and actively pursued a policy of eudemonism (making people economically happy) in exchange for accepting one-party rule.29 China's impressive economic development in the last two decades, coupled with the authorities’ intensive indoctrination for social stability and constant comparison of China with less stable democracies in Eastern Europe and the developing world, seems to have convinced many of its citizens that the current political system, although far from perfect, is the only viable system that can sustain economic growth and lead to China's success. I hypothesize that peasants who were more satisfied with their socio-economic conditions showed more affective support for the current political system in China.

Fear of socio-political chaos

Since the 1989 Tiananmen incident, the Chinese government has emphasized relentlessly the importance of political and social stability in developing the country's economy. In the early 1990s the Chinese media actively cited and reported the bad news coming out of the former Soviet Union and Eastern European countries that had just gone through fundamental social and political changes. The implication being that had China taken the path of the former Soviet Union China would have experienced political instability, economic decline, national disintegration, or even civil war.30 The Chinese government's repeated emphasis on stability struck a chord in the psyche of many Chinese people. They were reminded of luan or the chaos caused during the centuries of upheavals, rebellions, civil wars, and revolutions in contemporary Chinese history. The chaotic ten years of the Cultural Revolution was still fresh in people's minds. The perception in China that civil liberties and western-style liberal democracy bring chaos and instability is often reinforced by the experiences, shown in the Chinese media, of the new democracies in the developing world in the last two decades.

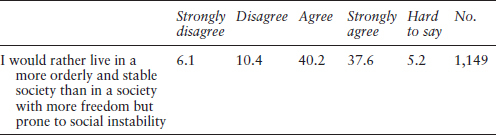

How would the rural residents in southern Jiangsu province view the question of social stability? The respondents in the survey were asked to agree or disagree with the statement ‘I would rather live in a more orderly and stable society rather than in a society with more freedoms but prone to social instability’. Close to 80 percent of the respondents seemed to prefer a more orderly society to a more free society which may experience social instability (see Table 5.6). The findings in Table 5.6 are similar to those found in the survey conducted in Beijing in the 1990s.31 They are also consistent with one China scholar's observation that the Chinese government's emphasis on social and political stability has led many young and old people in China to the conclusion ‘that China needs an authoritarian regime for fast and stable economic growth.’32 To a certain degree the Chinese government has been successful in convincing many Chinese people of the trade-off or choice between living in an orderly authoritarian society and a more free but prone-to-be-chaotic society. I hypothesize that fear of socio-political chaos among southern Jiangsu peasants is linked positively to their affective support for the authoritarian political system in China.

Prospective evaluations of economic and political conditions

Literature on political evaluations suggests that affective support for political systems is related in part to prospective evaluations of future economic and political conditions.33 Two studies on the former Soviet Union also indicate that citizens’ evaluations of future economic conditions at the national level are positively correlated with their support for the existing political regime. Based on a survey study, Willerton and Sigelman found that those who were more positive of future economic conditions tended to be more supportive of the current political regime.34 Another survey study by Duch showed that those who expected future economic deterioration would favor change or institutional reform in the current political system.35 His explanation is that people who were less optimistic about the future of the Soviet national economy perceived the existing political regime as an obstacle in solving future economic problems.36 I hypothesize that rural peasants’ prospective evaluations of both economic and political conditions (the same independent variable used in Chapter 3) reinforced their support for the political system in China.

Table 5.6 Fear for socio-political chaos (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Level of political interest

Do people who pay more attention to public affairs tend to show more affective support for the existing political system? Public opinion studies conducted in the United States show that people's political awareness leads to support for the prevailing political system's norms and values.37 In the United States most people receive their political information from the mainstream media which rarely challenges the fundamental values of the American political system, even though it may be very critical of particular governmental policies. In their study of popular support for the Brazilian authoritarian system, Geddes and Zaller also found a positive relationship between political interest and support for authoritarian norms.38 Today in China almost all news media (including both the printed and electronic media) and political communications are still controlled by the government, although the internet might be becoming an alternative news source for some college students, intellectuals, and middle-class professionals. Yet for the vast majority, particularly the peasants, the main or only news source remains the state-controlled media. Indeed, my survey found that close to 93 percent of peasants in rural Jiangsu get their news mainly from state-controlled media: 66.5 percent from TV, 20.9 percent from newspapers and magazines, and 5.5 percent from radio.

Following the same logic, it is reasonable to speculate that people in China who receive their news and information primarily from the state-controlled media are heavily influenced by the content of the news and, therefore, tend to be more sympathetic or supportive of the official political system and norms in China. In their study of Beijing residents, Chen, Zhong, and Hillard did find that levels of political interest and support for the political regime are positively related.39 Hence, I hypothesize that peasants in southern Jiangsu province who were more interested in political affairs tended to be more supportive of the current political system and norms in China. The same four ‘political interest’ questions used in Chapter 4 (see Table 4.1), paying attention to national affairs, paying attention to local and village affairs, discussion of national affairs with others, and discussion of local and village affairs with others, are used here as the independent variable for levels of political interest.

Key demographic control variables

Finally I will look into whether and how some key demographic control variables, such as age, gender, education, and income in multivariate analysis, influence my survey respondents’ affective support for the political system in China. Studies of established democratic, non-democratic, and transitional countries suggest that these key demographic factors do influence people's attitudes toward the political regime and/or political changes.40 In addition, these demographic factors need to be controlled to capture the effect of the other independent variables in this chapter.

Age

A number of studies of the former Soviet Union and China have noted that while older people in those countries tend to be more supportive of the existing political system the younger people are more likely to challenge the authoritarian regime and are more prone to change. In their study of the former Soviet Union, Finifter and Mickiewicz observed that youth in the former Soviet Union belonged to the ‘modern sector’ and were often the active participants of social and political movements for change while the older generation tended to be more resistant to change.41 The same phenomenon has also been observed in China. For instance, Chan and Nesbitt-Larking found that the younger respondents in their survey study were more critical of the Chinese government than those who were older.42 Zheng also noted that Chinese youth were more ‘individualistic’ and open-minded toward fundamental political change.43 It should be pointed out that young people were the main participants of the 1989 Tiananmen democracy movement, the single biggest protest movement challenging the existing political system in the PRC's history. Therefore, I expect that young respondents in the southern Jiangsu survey were less supportive of the current political system in China.

Gender

It is hard to predict how gender affects my survey respondents’ affective support for the Chinese political system. On the one hand, despite Chairman Mao's efforts and rhetoric in creating gender equality in the new China, inequalities between the sexes have never been eliminated, even during Mao's time.44 As mentioned before, gender inequalities have widened during the market reform era in areas such as employment, pay, treatment in the workplace, family roles, and socio-political status, since the role of the government has been reduced in those areas.45 TVEs in southern Jiangsu province hire many peasant women. On the other hand, the Chinese government at all levels still remains the last resort on which Chinese women depend to protect them against discrimination and unequal treatment. However, Chinese women tend to be more obedient to political authorities than their male counterparts.46 Therefore, it remains to be seen whether gender is a factor in political system support among peasants in southern Jiangsu province.

Education

Education has long been used as a predictor of political attitudes and behaviors. In their study Almond and Verba found that educational attainment has the most important effect on levels of civic culture.47 Education was also found to be related to regime support in the former Soviet Union. Specifically, the better educated tended to be more critical of the communist regime, despite official indoctrination at school.48 As Silver noted, ‘Advanced education is likely to be intellectually liberating and to induce a more critical stance toward official dogma.’49 Many China scholars have argued that Chinese intellectuals tend to be regime challengers and have spearheaded many of the social and political movements in the twentieth century, noticeably the May 4th Movement.50 Based on the observations and arguments above I hypothesize that the better-educated peasants in southern Jiangsu province would be less supportive of the political system in China.

Income

Income is closely related to the variables life satisfaction and prospective evaluation of economic and political conditions. The rationale is the same, that is, people who are better off tend to be less likely to challenge the existing system. As the old saying goes, ‘if things are going well, why rock the boat?’ Indeed, as a number of empirical studies on Chinese political attitudes and behavior have found, people of a higher income bracket tend to be conservative in their political orientation. Therefore, I hypothesize that people with higher incomes tended to be more supportive of the current political system in China.

Multivariate analysis

Table 5.7 presents the results of multivariate analysis for political regime support among peasants in southern Jiangsu province. Taken together, evaluations of government policy performance, the level of political content with local officials, life satisfaction, fear of socio-political chaos, prospective evaluation of China's economic and political conditions, the level of political interest, and the key demographic attributes explain close to 20 percent of the variance in support of the political regime in China. Most of the independent variables are significant in explaining the level of affective support for the Chinese political system among rural residents in southern Jiangsu province. Findings in the study lend support to the performance or eudemonism-based legitimacy for the CCP.

Most noticeably, evaluations of central government policy performance and prospective evaluations of economic and political conditions are the strongest predictors of affective support for the existing political regime in China. As hypothesized, people who gave higher marks to central government policy performance tended to be more supportive of the political regime in China. It was also found that southern Jiangsu peasants who were more content with their local officials’ behavior gave more support to the Chinese political regime. These findings confirm the close relationship between instrumental support and affective support. Positive instrumental support strengthens people's affection for the political system.

Table 5.7 Multivariate model of popular support for China's political regime

Support for political regime |

|||

Unstandardized coefficient |

Standardized error |

Beta weight |

|

Independent variables |

|||

Evaluations of central government performance |

0.09 |

(0.01) |

0.24*** |

Level of political content with local officials |

0.07 |

(0.02) |

0.10*** |

Life satisfaction |

0.10 |

(0.07) |

0.05 |

Fear of socio-political chaos |

0.21 |

(0.09) |

0.07** |

Prospective evaluations of China's economic and political conditions |

0.51 |

(0.07) |

0.21*** |

Level of political interest |

0.07 |

(0.02) |

0.10*** |

Demographic variables |

|||

Age |

0.00 |

(0.02) |

0.04 |

Gender (female = 1, male = 2) |

–0.08 |

(0.13) |

–0.01 |

Education |

–0.02 |

(0.08) |

–0.01 |

Income |

0.04 |

(0.02) |

0.05* |

Constant |

5.70 |

(0.82) |

|

Multiple R |

0.445 |

||

R² |

0.198 |

||

Adjusted R² |

0.190 |

||

Note

In addition, people who felt more confident of prospective economic and political conditions also tended to show more affective support for the current political regime. Income is also a significant factor in affecting people's support for China's political system, even though life satisfaction did not turn out to be a predictive factor. These findings only partially confirm the eudemonism-based legitimacy for the CCP. It has to be recognized that the Chinese government has performed well economically since the 1980s. There is no doubt that people's living standards in China have improved substantially over that last three decades, although the gap between rich and poor has widened significantly. China has become the second largest economy in the world and a major trading power. The CCP's good performance has certainly improved its legitimacy since Tiananmen.

Moreover, it seems that there is a positive relationship between the fear of socio-political chaos and the level of regime support. Specifically, people who were more afraid of socio-political chaos tended to be more supportive of the political regime in China. This finding implies that the Chinese government's relentless effort to emphasize the theme of ‘stability first’ might have worked by increasing popular support for the current political regime. Also, as expected, interest in political and public affairs is also related to political regime support. Respondents in the survey who paid more attention to politics were more supportive of the existing political regime in China.

Among the demographic factors, it seems that older people, women, and people with a less formal education tended to be more supportive of the current political regime in the southern Jiangsu rural survey. However, the factors of age, gender, and education are not statistically significant. Overall, the multivariate analysis results suggest that popular support for the current Chinese political regime is most likely to be found among those who have positive evaluations of the central government's policy performance, who are more optimistic about the country's economic and political future, who are more satisfied with their local government officials, who are economically better off, who are more afraid of socio-political chaos, and who pay more attention to political and public affairs.

Conclusion

The Chinese Communist Party was carried to power partly by peasant support in the 1940s. The first group of people who benefited from the economic reforms in the 1980s were Chinese peasants. The support of the peasantry is likely to be important for the CCP's future, since 70 percent of the Chinese population are still peasants or residents with rural household registration. This chapter attempts to explore the level of support for the current political regime among southern Jiangsu peasants through a public opinion survey. Descriptive findings from this survey with regard to regime support may not be necessarily representative of the peasant population for the rest of China. However, the analytical findings have significant implications across China.

Descriptively, the level of support for the current Chinese political regime registers moderate to high among southern Jiangsu peasants. Most of the respondents in the survey said they were proud of living under the current socialist system, felt that their values were the same as those advocated by the Chinese government, believed that they had an obligation to support the political system in China, respected governmental institutions in China, and trusted the Chinese court system. It was also found that most of the peasants in southern Jiangsu province gave a passing to moderate grade to central government performance in most of the eleven policy areas, and they were modestly satisfied with local government officials’ performance. Obviously we should bear in mind that rural southern Jiangsu province is one of the most economically developed areas in China, and peasants there enjoy a much higher standard of living than their counterparts in other parts of China. Therefore, the above descriptive findings should not be generalized to the rest of the Chinese countryside.

Results from the multivariate analysis, however, are potentially applicable to the rest of rural China. We know from the findings that good Chinese government performance in public policy and local government officials’ behavior contribute to the CCP's legitimacy and popular support among Chinese peasants. It was also found that income level and prospective evaluations of political and economic conditions are significantly related to peasants’ support for the Chinese political regime. The findings suggest the CCP's strategy of improving its political legitimacy by good governance and improving people's living standards has been working. Furthermore, fear of socio-political instability is an important factor in increasing peasants’ affective support for the current political system in China. Since 1989, the CCP has been engaged in both positive and negative regime legitimization tactics. Positive legitimization refers to a regime's effort to increase its political legitimacy by making the regime more attractive through measures such as improving performance, adopting popular policies, and democratizing the political system. Negative legitimization refers to a regime's effort to increase its political legitimacy by painting the alternative as even more undesirable or even totally discrediting and delegitimizing it. 51 The result of the Chinese government's negative legitimization is that many people in China equate western-style democracy with a potential for chaos. The multivariate analysis shows that people who are more afraid of socio-political chaos tended to be more supportive of the current political regime in China.

Findings from the multivariate analysis do not paint a totally rosy picture for the Chinese government. Since the CCP's legitimacy is largely dependent on government public policy performance and continued economic improvement, bad government policy performance and stoppages or even a slowdown in improvements to living standards will no doubt seriously erode the legitimacy of the Chinese government. We already found in the survey that a substantial number of the respondents were not happy with the Chinese government's efforts at narrowing the widening gap between rich and poor and in fighting official corruption. The situation on these two fronts has become worse since the survey was done in 2000. The Chinese government is trying to achieve legitimacy ‘the hard way’ by relying heavily on economic performance. Obviously, no country can maintain a high level of economic growth forever. The pitfall of economic performance-based political legitimacy is that if the economy goes sour, the CCP may have little else to fall back on, since the regime lacks democratic legitimacy. It seems that the CCP has fallen into an intractable trap. The reform has become a process of both legitimation and delegitimation. On the one hand, to salvage its legitimacy to rule, the CCP had to shift its legitimacy basis, by and large, from ideology to economic performance. On the other hand, whatever legitimacy the CCP has gained through economic reforms has been undermined by the irreconcilable nature of the economic reforms with the official communist ideology and the negative consequences of the reforms (such as official corruption, a widening gap between rich and poor, and unemployment). A prolonged economic malaise will seriously erode the CCP's claim of exclusive power in China. That is why, for the CCP, maintaining a high economic growth rate is more of a political issue than an economic one, since it concerns the very survival of the regime. In fact, I would argue that legitimacy and relegitimation will be a constant struggle for the CCP as long as it does not significantly change its political system.