3 Support for the market economy

China's dramatic economic transformation from a strict command central-planning economy to a by-and-large market economy in the past 30 years is nothing short of a miracle. After 30 years of double-digit economic growth, China has become the second largest economy after the United States and one of the top trading countries in the world. Obviously many factors have contributed to the rapid economic growth of China in the past three decades. This chapter focuses on the cultural aspect of economic growth in China. It has long been argued whether China's predominantly Confucian culture is conducive to a capitalist market economy. Max Weber might have turned in his grave to explain the flourishing market economy in China today. In fact, capitalism, as an economic system, had already been successfully adopted by other Confucian-influenced countries in East Asia, such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, before the 1970s when China started economic reform. China's capitalistic economic reforms have rekindled the debate about the relationship between Confucian culture and capitalism.

China's market-driven economic reform started in rural China in the late 1970s. Communes, which were set up in the 1950s, were abolished in the early 1980s and were replaced with the Household Responsibility System (HRS) or individual private farming. Not only did Chinese peasants become independent farmers under the new system, many of them also became entrepreneurs running their own businesses. Hundreds of millions of Chinese peasants have also become migrant workers in the cities. What is the attitude among southern Jiangsu peasants toward the market-driven economic reform? How supportive are they of the new economic system? How is their support or lack of it related to such factors as their perceived benefit from the new system, prospective evaluation of China's economic future, democratic orientation, and so on? How does their attitude toward market-driven economic reform compare with residents in Beijing? These questions will be answered in this chapter.

Chinese culture and economic development

Max Weber was one of the first scholars who linked culture to economic development. In his The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism,1 Weber explained why capitalism first emerged in predominantly Protestant countries and regions. Weber believed that the emergence of ascetic capitalism was an unnatural and painful experience. He wondered why people would be willing to go through such a painful process and what motivated them to overcome the hurdles of initial capitalist development.2 Weber did not believe that Protestants were necessarily more worldly than believers of other regions. Instead, the entrepreneurial spirit, the work ethic, and the pursuit of material gains and wealth among Protestants, particularly the Calvinists, are justified by religious rationalization. Hard work, in the mind of Protestant believers, is seen as dedication to God and material gains as reward from God. According to Weber, Calvinists in particular suffer from ‘salvation anxiety’ due to the concept of ‘predestination’ (one's fate in the future is sealed before one's birth). Due to the uncertainty and anxiety about their after-life, Calvinists look for signs of their salvation. Success in life, including material success, is considered a positive sign that they are among the ‘chosen’.3 In other words, Protestants work hard for a religious purpose, to please their God, instead of for material gain. This Protestant ethic coincides with the spirit of capitalism, namely, one works hard not because one has to or for material gain, but rather one enjoys the work.

Weber specifically singled out China as an unlikely candidate for capitalistic development due to its Confucian and Daoist culture and traditions. Confucianism is most concerned with the perfection of man through literary schooling and turning man into gentleman. Confucianism and Puritanism differ over rationalism. Confucian rationalism concerns rational adjustment to the world, while Puritan rationalism is about rational domination of the world.4 According to Confucius, young people should devote their life to formal education, and the goal of studying hard is to become public officials (xue er you ze shi). Traditional Confucianism, in general, looks down upon commercial activities and the acquisition of wealth. In Chinese history businessmen tended to do everything possible to make their children study hard in order to become prominent officials. In the traditional scholarly official system, officials were recruited through rigid examinations based on classical Chinese literature and Confucian teachings. Timothy Brook observes that many Chinese intellectuals are still ambiguous and even negative about profit even after more than two decades of market economic reform.5 Moreover, according to Weber, Confucianism and the Chinese traditional practice of ancestral worship are too concerned with family and clan ties; while Protestant sects believe in a community of faith beyond blood ties, which makes it easier for Protestants to engage in universal business practice.6 In addition, concepts such as salvation, freedom, natural law, and individual rights are all absent in Confucianism.7 In short, Confucianism is no Protestantism. Weber did not believe that Chinese Daoism was conducive to capitalism either since Daoism is most interested in escaping from this world.

Is Chinese culture or Confucianism necessarily resistant to capitalism? The phenomenal economic growth and development of a market economy in Confucian-influenced countries such as Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and mainland China apparently pose a serious challenge to Weber's theory and predictions. It seems that East Asians have embraced capitalism with open arms. Margaret Thatcher once said that the Chinese are ‘born capitalists’. Did the flourishing of capitalism in East Asian countries occur despite the oriental cultures and traditions or because of them? The answer lies in a combination of both. Certain aspects of Confucian values such as hard work, thrift, and emphasis on education facilitate capitalist development in East Asia,8 while some other aspects of Confucian culture as were pointed out by Weber pose as barriers to capitalist development in the region. Yu Ying-shih, a well-known Confucian scholar, observes that Confucians beginning in the late Ming dynasty were already receptive to commercial economic activities and elevated merchants’ status to the mainstream of society. Yu further boldly argues that the neo-Confucians since the Song dynasty have cherished the values of hard work, thrift, and honesty, all of which are conducive to commercial activity. In fact, contrary to Weber's negative perception of the relationship between Confucianism and capitalism, Yu believes that neo-Confucianism fostered commercialism in China.9 Not only has Confucianism positively contributed to China's economic development, the various versions of Confucianism have also been cited as facilitating factors to economic development in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.10

Even though peasants are often not specifically mentioned in the studies on the relationship between culture and capitalist market economic development in China, they are implicated as bearers of traditional Chinese culture. After all, China has been a predominantly peasant society. It certainly can be argued that China's predominantly peasant culture falls squarely on the traditional side of Talcott Parsons's five pattern variables that distinguish between traditional and modern values: affection vs. affection-neutral, collective-orientation vs. self-orientation, particularism vs. universalism, ascription vs. achievement, and functional diffuseness vs. functional specific.11 Marxism is also critical of the peasant class which is perceived to be backward and feudal. However, are Chinese peasants necessarily resistant to modernization and market economic development? According to Philip Huang, there are three different faces of Chinese peasants: the face of a subsistence farmer, the face of an entrepreneur, and the face of an agricultural producer supplying the consumption needs for the non-agricultural sectors.12 The peasant as an entrepreneur behaves very similarly to a businessman who is concerned with supply and demand and prices. The entrepreneur peasant is often neglected in the literature. In fact, rural commercialism was an integral part of the Chinese economy for centuries. In his study Bin Wong demonstrates that rural commercialization and market exchanges were facts of life in Chinese history even though Chinese officials and elites were uneasy and anxious about the ‘unbridled pursuit of profit’ and the ‘prominent display of extravagance’.13 The entrepreneurial spirit of the Chinese peasants is even more revealing and striking during the economic reform of the last three decades in China.

Chinese peasants and China's market reform

Interestingly enough, China's market-oriented economic reform started in the Chinese countryside. Throughout the reform era Chinese peasants have been active participants of the reform enterprise and have been a significant factor contributing to the success of China's market-driven reforms. After the Chinese communist takeover in 1949, Chairman Mao promised sweeping land reform by redistributing land from landlords to landless peasants between 1950 and 1953. However, Chinese farmers did not hold their land for long. Owing to industrial and ideological reasons, in 1953 Chairman Mao introduced programs to collectivize rural farmland in China. Chinese farmers were first organized into ‘mutual help teams’, which were later transformed into ‘elementary cooperatives’ and ‘advanced cooperatives’. The collectivization process was finally completed with the establishment of ‘people's communes’ all over the country in 1958. However, the legal and constitutional status of people's communes was only recognized by a new state constitution adopted in 1975.

A people’ commune was more than an agricultural collective organization. It was also a political and administrative unit. In fact, people's communes replaced township government to become the lowest level of government in rural China. Communization brought disastrous consequences for the Chinese peasants. It is estimated that between 10 million and 40 million Chinese died of starvation in the famine between 1959 and 1961 that resulted partly from the collectivization drive. Most of the dead were peasants. Despite the official propaganda, the collectivization process met a lot of active and passive resistance from Chinese peasants.14 Many peasants demanded to withdraw from the collective farm after they realized the promises made were not delivered. In fact, Chinese peasants never stopped trying to return to private farming during the commune period between the 1950s and 1970s.15

Communes were formally abolished and were replaced with the new baochan daohu (‘contracting production to the household') system or the ‘household responsibility system’ in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. It should be pointed out that the decollectivization drive was initiated by farmers in a small village in Anhui province in 1978 and the trend spread to other regions of rural China rapidly. The Chinese government first tried to stop the move and then attempted to restrict the new system only to the poorest rural areas. It was not until 1981 that the Chinese government finally allowed the new system be adopted nationwide.16 In the new baochan daohu system, each household was allocated a piece of land to cultivate and peasants were given much more freedom to grow what they liked and to price their products. However, the ownership of the land still belonged to the collective.

Under the new system farmers in China became agricultural entrepreneurs again. The baochan daohu system provided significant material incentives for Chinese farmers to engage in efficient agricultural production and contributed to the impressive agricultural growth in China in the 1980s. The average annual growth rate for crops between 1978 and 1984 was 5.9 percent, compared to 2.5 percent between 1952 and 1978, and the average annual growth rate for husbandry jumped from 4 percent to 10 percent between 1978 and 1984.17 By using panel data from 28 of 29 Chinese provinces, Justin Yifu Lin convincingly demonstrated that the adoption of the baochan daohu system was the dominant factor in increasing agricultural output between 1978 and 1984.18 The agricultural reform was so successful that the Chinese government got rid of food rationing and became a net food exporting country in the 1980s.19

Another area in which Chinese peasants have exhibited tremendous entrepreneurial spirit is the ownership of various rural industries during the reform era. In fact, rural industries owned and run by communes and collective production brigades and teams already existed during the pre-reform period, mostly in wealthy provinces such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Shandong, as a result of Mao's irrational industrialization policy during the Great Leap Forward Movement. Rural industries or Township and Village Enterprises (TVEs) boomed and became one of the most vibrant economic forces in China between the 1980s and the 1990s. The number of rural enterprises quadrupled between 1979 and 1986 (from 1.48 million to 6.35 million) employing 47.6 million Chinese peasants and with a production of 23 percent of China's national industrial output in 1986.20 The ownership models of Chinese rural enterprises might vary across regions, for instance, the Sunan model (collective enterprises in southern Jiangsu province) and the Wenzhou model (private ownership in Wenzhou area in Zhejiang province). Both models succeeded. Chinese governmental officials, including Deng Xiaoping, were pleasantly surprised by the rapid development of rural enterprises since they were not planned.21 It should be noted that Chinese rural enterprises at the time had to compete with the state industries from a very disadvantageous position. They lacked funds and technology and had the added difficulties of getting raw materials and accessing the market.22 Why did rural enterprises in China flourish and succeed in the 1980s? There are many factors explaining their success. One of them is that rural enterprises, compared to the rigid and bureaucratic state industries, were flexible and adaptable to the market.

However, another major factor is Chinese peasants’ entrepreneurial spirit and work ethic. Chinese peasants obviously saw an opportunity to improve their lives in a more open economy and grabbed it. There are many rags-to-riches stories of Chinese peasant entrepreneurs. One of them was Yu Zuomin, a village official who successfully built his village, Daqiu near Tianjin, into the richest village in China in the 1980s.23 Born into a peasant family and barely literate, Yu became the face of Chinese peasant entrepreneurs between the mid-1980s and early 1990s. Tired of being very poor and of Mao's communist policies of the 1960s and the 1970s, Yu, encouraged by his villagers, started a strip mill in 1977 with $26,000, money from both the village collective fund and the county government. A steel pipe factory and a printing plant were built in 1979 and 1980 respectively. In the early 1980s Yu incorporated the factories and set up a conglomerate called the Daqiu Village Agriculture, Industry, and Commerce United Company.24 By the mid-1990s the conglomerate had 335 enterprises and 40 of them were joint ventures with foreign companies.25 Even though Yu Zuomin and several dozens of other Daqiu officials and villagers were sentenced to prison terms for alleged crimes such as stealing state secrets, harboring criminals, and obstructing justice in 1993, it does not take away the fact that Yu was one of the most successful peasant entrepreneurs in modern China.

Another group of successful peasant entrepreneurs was the Liu brothers: Liu Yongyan, Liu Yongxing, Liu Yonghao, and Chen Yuxin (who was given up by his birth parents at an early age) from China's Sichuan province.26 With their rural background, the Liu brothers started their business empire by initially setting up a feed mill (later called the Hope Group) in their village in 1982 after they decided to resign from their guaranteed state sector (or ‘iron rice bowl') jobs. They first dominated the feed market in Sichuan, the most populous province in China in the 1980s, and later set up feed mills all over China. By 1992, the Hope Group had grown so big that the Liu brothers decided to split it into four different companies along geographic lines covering a wide array of industries and sectors from power plants to finance, and from electronics to real estate. The Liu brothers, now worth billions, have become the richest family in China. It is worth mentioning that a number of business tycoons in Taiwan and Hong Kong also came from rural backgrounds.

Due to a combination of factors such as poverty, relaxed population control policies, and opportunities presented by economic reform, hundreds of millions of Chinese peasants, both men and women, have migrated to the cities or developed rural areas to work in factories and other places. Migrant workers have become an indispensible labor force for any urban centers in China and one of the most important driving forces behind China's economic growth. In the meantime, the migration of farmers into the cities also partly solved the underemployment problem in the countryside for the Chinese government. In addition, migrant farmers sent much-needed cash back to their home villages. Many migrant peasants have gone back to their villages to start small businesses with the money they made in the cities. Most importantly, many migrant farmers’ values changed after working in the factories and being exposed to modernization. However, much like poor Mexican immigrant workers in the United States, Chinese peasant migrant laborers usually work in the jobs that few urban residents want to do. They work long hours, in poor working conditions and without job security, and suffer from discrimination by urban dwellers and periodic police harassment.27 There is little doubt that Chinese peasant migrant workers are the most exploited people in China. Owing to China's rigid bifurcated rural– urban household registration (hukou) system, peasant migrant workers have little chance to become legal permanent urban residents in China.

Considering that Chinese peasants have actively participated in the market-driven economic reforms in China and have been one of the major forces behind China's rapid economic growth in the past few decades, it is not surprising that peasants in the southern Jiangsu survey were mostly supportive of the market reform in China over the past three decades (see Table 2.5 in Chapter 2). The support for the market economy in southern Jiangsu province was evidently strong. Very few of the respondents supported either a totally planned economy or a partially planned economy. Hardly any supported a genuine mixed (half planned and half market) economy. The majority of our peasant respondents (56.6 percent) were in favor of a market-driven economy. The level of support for the market economy among southern Jiangsu peasants was even higher than that in Beijing. The level of support for a market economy among southern Jiangsu peasants was comparable to that of citizens in the former Soviet Union. A survey of Soviet citizens conducted in the European USSR in May 1990 showed that 54.3 percent supported market-driven reform when market reform in the former Soviet Union was just being introduced.28 Answers to the question concerning support for a market economy or a planned economy were tallied and added to form an additive index to be used as the dependent variable of support for market-driven economic reform in the multivariate analysis.

Independent variables

Who, among Chinese peasants, is more likely to support market-driven economic reforms? What factors affect Chinese peasants’ support for economic reform? When studying the support for market reforms among citizens in the former Soviet Union, Raymond Duch examined a number of explanatory factors, such as free-market culture, retrospective and prospective evaluations of the Soviet economy, democratic orientation, age, and level of education.29 Many of these factors can be applied to my study of southern Jiangsu peasants’ support for a market economy in China. Specifically, I will include free-market culture or value, satisfaction with socio-economic conditions, prospective evaluation of the Chinese economy, democratic orientation, political efficacy, and some socio-demographic variables (such as age, gender, and education) in the multivariate analyses.

Free-market value

Just as democratic political institutions can only survive in a mass democratic cultural environment, a market economy needs a hospitable culture for its sustainment. Preference for a market economy is supposed to go hand in hand with market culture or value. However, as Raymond Duch pointed out, support for a market economy is not synonymous with free-market value.30 The former concerns a preference for specific market-oriented institutions, mechanisms, and policies, while the latter involves a deeper free-market belief system or philosophy. A person may support a market system while favoring more egalitarian government distribution policies (such as higher taxes for the rich and/or more social welfare for the poor).

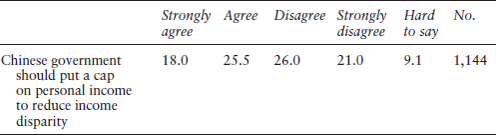

One of the questions in the survey was: ‘Should the government put a cap on people's personal income to prevent income disparity?’ This question taps into the survey respondents’ free-market value or belief. Are Chinese peasants still egalitarian in their economic outlook? After all, peasants in China lived in ‘people's communes’ with extreme egalitarian practices between the late 1950s and the early 1980s. Table 3.1 shows that the respondents were split almost in the middle as to whether the government should cap people's income to prevent a widening income gap. Close to half (47 percent) of them gave a negative answer to the question, while 43 percent favored an income cap. These findings have to be understood in the context of a widening income gap in China. During the reform era China has become a much more unequal society with differential incomes. According to World Bank, China's Gini coefficient was as high as 0.447 in 2001 (surpassing the warning line of 0.4), higher than that in all developed countries and most developing countries.31 Only two Asian countries, Malaysia and the Philippines, had a higher Gini co-efficient than China. The uncomfortable feeling about the increasing income gap was reflected in our survey. When the respondents were asked whether the income gap was growing too big, an overwhelming majority (82.9 percent) believed that it was. Despite the income gap, it is remarkable that close to half of the respondents were opposed to capping individuals’ incomes. It shows that many peasants in southern Jiangsu province, who had lived in people's communes for over 30 years and still had a predominantly collective economy when the survey was conducted, did not favor governmental intervention in controlling people's income. It is hypothesized that free-market value or belief system fosters support for a market-driven economy.

Table 3.1 Support for government intervention in controlling income (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Satisfaction of socio-economic conditions

It is reasonable to assume that Chinese peasants’ support for a market economy is related to whether they have benefited from the market-driven economic reforms during the reform era. Individuals are rational actors and tend to act on their own self interest. Economic self interest or ‘pocketbook’ considerations are often a determining factor in a citizen's choice for choosing an incumbent party/candidate or an opposition party/candidate in democracies. The oft-asked question is: ‘Are you better off today than four years ago?’ Dissatisfaction with personal socio-economic conditions is most likely to result in a voter's decision to opt for an alternative political party or candidate. Raymond Duch found that the former Soviet citizens who were less satisfied with the existing economic conditions tended to support market-driven economic reform.32 Since China was already undergoing market reform by 2000, it is hypothesized that peasants in southern Jiangsu province who were satisfied with improvement of their personal socio-economic conditions would be more supportive of a market economy. As shown in Table 2.3, most people (close to 90 percent) in our survey indicated that their living conditions had noticeably improved in the reform era and 65 percent of them said that their social status had also improved in the same period. Closely related to satisfaction in life is the income factor. Thus, it is also hypothesized that southern Jiangsu peasants with higher incomes would show more support for the market economy since they are the beneficiaries of the ongoing market-driven economic reforms.

Prospective evaluation of the Chinese economy

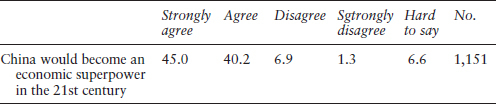

The same rationale also holds for the relationship between the prospective evaluation of the economic condition and support for the current existing economic system. If someone is optimistic about the future of the economy, he or she is likely to be positive about the current economic system. In the former Soviet Union, people who believed the planned economy would deteriorate tended to support the introduction of a market economy.33 Therefore, it is hypothesized that a positive relationship between confidence in China's economic future and support for a market economy among peasants in southern Jiangsu province would exist. Table 3.2 shows that around 85 percent of our respondents believed that China would become an economic superpower in the twenty-first century.

Democratic orientation

As demonstrated in Chapter 2, support for a free market economy and support for core democratic values are (positively) related among southern Jiangsu peasants. The positive relationship between the two has been well explained by scholars such as Schumpeter, Moore, Lindblom, and Almond.34 Free market belief and democratic belief share one inherent and fundamental principle: the principle of free choice. In a free market economy, consumers are free to choose products based on price and quality in a marketplace. In a similar fashion, democratic politics allows citizens or voters (the ‘consumers') to choose policies (the ‘products') represented and presented by politicians (the ‘producers') based on ideology and preferences in elections or referendums (the ‘market'). In addition, both the market economy and democratic politics are predicated on the rule of law, freedom of information, and freedom of movement. In his study of the former Soviet Union, Raymond Duch found that democratically oriented Soviet citizens were more supportive of market reform.35 It is, therefore, hypothesized that core democratic values (see Table 2.1 for core democratic values among survey respondents) are a strong predictor for preference for a market-driven economy.

Table 3.2 Prospective evaluation of Chinese economy (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Political efficacy

Political efficacy is the confidence that citizens have in their ability to influence or have an impact on the political process. Political efficacy and free-market belief share something in common: confidence in oneself. While political efficacy is concerned with one's ability and confidence in making a difference in the political world, the market economy requires its participants to be self reliant and to make independent decisions in the market place. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that political efficacy and support for a market economy are positively related. As shown in Table 2.6, answers to the two political efficacy questions were mixed in the survey. While most of the respondents believed that the well-being of the country should depend on the masses, not the leaders, most of them were also reluctant to argue with authorities even though they thought they were right. Answers to these two questions were summarized and formed the independent variable of political efficacy.

Socio-demographic variables

A number of important socio-demographic variables were also included in the multivariate analyses. Raymond Duch did find that the better educated and the young were more in favor of market-oriented economic reform in the former Soviet Union.36

After all, a modern market economy is a competitive economy favoring the better educated, the more skilled, and the young. Using the same rationale, it was also expected that young respondents with a better education in the rural southern Jiangsu province would show more support for a market economy since they tended to benefit more from such an economy. It is hard to speculate how gender might play a role in favoring or disfavoring a market economy. It should be noted that rural China is still a male-dominated society and men are the main bread winners in the countryside. For this reason alone, it is possible that more men might favor the market economy than women among the survey respondents.

Multivariate results and conclusion

Table 3.3 displays the results of multivariate analyses. As expected, core democratic values have a strong positive impact on preference for a market economy. In other words, peasants in my survey who believed in core democratic values tended to be more supportive of a market economy. Similarly, peasants in southern Jiangsu province who showed more political efficacy were also more in favor of a market economy. The multivariate analyses also indicate that prospective evaluations of China's economy are positively related to the support for a market economy. People who were more positive about China's economic future showed more support for a market economy. Contrary to my expectations, satisfaction with one's socioeconomic status was not related to one's support for a market economy. However, people in the survey with higher incomes showed more support for a market economy. Also, contrary to my hypothesis, free-market value did not seem to have much impact on one's support for a market economy. It is worth pointing out that the free-market value was only measured through one question: Should the government put a cap on income to prevent the widening income disparity? It is possible that one survey question cannot capture people's deep belief or non-belief in free market economy. Among the socio-demographic variables, it seems that respondents with a better education tended to be more supportive of a market economy and men were more in favor of a market economy than women. However, age did not seem to be a factor in deciding one's preference for a market economy in the survey. It should be noted that the percentage of variance explained in the multiple regression model is small.

Studies have shown that even in history Chinese peasants exhibited extraordinary entrepreneurial spirit and had a long history of engagement in rural commercialism. Even during the height of the people's commune system, many Chinese peasants, often in a clandestine and disguised fashion, kept their small private farming lot and engaged in rural market exchanges. The entrepreneurial spirit among Chinese peasants is even more vividly demonstrated in the economic reform era. Throughout the reform era, peasants have been major participants in the evolving Chinese market economy. Peasants were the initiators and supporters of changing from the commune system to private farming. The new baochan daohu system was so successful that China became a net food exporting country in the 1980s. The successful rural economic reform also laid the foundation for China's double-digit economic growth in the last three decades. One area in which Chinese peasants have shown impressive entrepreneurial spirit is rural industries (both collective and private). TVEs have become an indispensable part of the Chinese economy today. Moreover, millions upon millions of Chinese peasants have moved to the cities to work in factories and construction sites, playing an important role in China's rapid industrialization drive.

Table 3.3 Multiple regression in support of a market economy

Independent variables |

Support for a market economy |

|

Non-standardized coefficient |

Standard error |

|

Free market value |

0.039 |

0.027 |

Socio-economic satisfaction |

0.027 |

0.025 |

Income |

0.029** |

0.010 |

Prospective evaluation of China's economy |

0.054* |

0.031 |

Democratic values |

0.024*** |

0.009 |

Political efficacy |

0.065*** |

0.020 |

Demographic attributes |

||

Age |

0.003 |

0.002 |

Education |

0.125*** |

0.036 |

Gender (female = 0; male = 1) |

0.101* |

0.057 |

Constant |

69.257*** |

0.853 |

Multiple R |

0.261 |

|

R2 |

0.068 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.060 |

|

Note

All of these seem to defy the conventional wisdom that Chinese culture and Chinese peasants are resistant to a market economy and capitalism. What are the attitudes of Chinese peasants toward a market economy? The survey data show that most of southern Jiangsu peasants (close to 60 percent) did support a complete or mainly market economy, while only less than 10 percent preferred either a complete or mainly planned economy. The level of support for a market economy among southern Jiangsu peasants was even higher than that among Beijing urban residents.

If a market economy is a crucial part of capitalism, it is hard to argue that Chinese culture or Chinese peasants are necessarily unreceptive to capitalism in light of the survey findings among southern Jiangsu peasants.