4 Levels of political interest1

As mentioned earlier, the Chinese peasantry has historically been viewed as a conservative social and political force. It is often perceived as ill-informed and lacking the necessary cognitive knowledge about public affairs and political events.

To what degree are Chinese peasants interested in politics (that is, national and local political affairs) and what factors affect their political interest? These are the two central questions that will be addressed in this chapter. A study of these questions carries both theoretical and practical implications. The importance of political interest as psychological involvement in politics and public affairs has been well observed and documented by western scholarship.2 Psychological involvement in politics and public affairs is regarded as a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for active political participation. Verba and his associates observed in their empirical cross-national study that those who were more interested in politics out-participated those who were apathetic to politics.3 Similar findings were also reported by scholars studying the former Soviet Union.4 For example, in their empirical study of mass political participation of the former USSR, Bahry and Silver found that those who were more interested in politics were more likely to engage in conventional and/or unconventional political activities.5 Therefore, the theoretical implication is that such a linkage between the level of political interest and political participation may also exist in China, a transitional society. A practical implication is that if there is a high level of political interest among the Chinese peasantry found in this study, it may indicate a certain degree of political uneasiness on the part of the peasants and may lead to higher levels of peasant participation in conventional and/or unconventional political activities in southern Jiangsu province.

Given the intricate relationship between the level of political interest or psychological involvement in politics and likely participation in political activities, it becomes important that we understand who are more likely to have higher levels of political interest and what factors may lead someone to be psychologically involved in politics. Levels of political interest as a separate dependent variable have, unfortunately, not been sufficiently studied in an empirical fashion by China scholars both inside and outside China. In the limited number of empirical studies, political interest was either treated as an act of political participation6 or as an independent variable.7 Few of them explore the degree and sources of psychological involvement in China. A survey conducted by Chen and Zhong in the mid-1990s focused on mass political interest and apathy levels and contributing factors.8 They found that there was a relatively high level of political interest among Beijing residents, contrary to the prevalent perception that Chinese people were politically apathetic and shifted their attention to the pursuit of materialism after years of constant political campaigns between the 1950s and the 1970s. They further found that age, gender, income, political status, political efficacy, and life satisfaction had significant impacts on the levels of political interest among Beijing residents. However, this study was conducted in an urban setting and in the capital city of China.

Levels of political interest among peasants in southern Jiangsu province

How much do Chinese peasants still care about politics and public affairs in the reform era? Literature on Chinese political culture and participation often describes three relatively distinct stages with regard to mass political interest in contemporary China. The first stage was before the 1949 Chinese Communist revolution, when most Chinese seemed to be politically apathetic and ignorant.9 This stage was also characterized by one China scholar typified as a ‘popular isolation from politics’.10 The second stage between the 1950s and 1970s was marked by a ‘participation explosion’ due to the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) sustained mobilization efforts that led to unprecedented enthusiasm on the part of the population about public and political affairs, especially during the decade of the Cultural Revolution.11 In fact, political participation (in terms of private citizens’ efforts to influence public affairs) in the Chinese countryside was much more active than many people thought during this period. Peasants used various means to protect and voice their interest, including state institutions (such as local assemblies, mass organizations, elections, and media) and non-conventional activities (such as passive resistance and collective violence).12 During the third stage, which covers most of the post-Mao reform period and continues to the present, a popular perception among China observers is that the Chinese people are consumed with acquiring material goods and making money and have become increasingly apolitical and pragmatic.13 Deng Xiaoping's slogan ‘Getting rich is glorious’ carries the day in modern China. Is this a true picture? An advantage of survey research, if properly done, is that it enables us to describe people's attitudes, opinions, and orientations precisely.

Political interest in this study is defined as an individual's degree of interest in and concern with government and public affairs. It should be noted that the concept of political interest in this study is different from the concept of political participation, even though the two concepts are somewhat related. Political interest is the psychological involvement for political and public affairs,14 while political participation is about a pattern of action or inaction in politics and public affairs.15 Although those who are more interested in politics are more likely to participate in politics, high levels of psychological involvement in politics and public affairs do not always translate into political participation because of institutional constraints and a lack of resources. Even in a democracy, as Dahl has noted, it is considerably easier to be merely interested, which demands only passive participation, than to be active in politics; interest costs little in terms of physical energy and time; and activity demands much more.16

I used four questions in the survey to measure levels of mass political interest among southern Jiangsu peasants. They were: ‘Are you interested in national affairs?’, ‘Are you interested in public affairs in your village and county?’, ‘How often do you talk about national affairs with others?’, and ‘How often do you talk about village affairs with others?’ The operationalization and measurements of political interest are derived from Almond and Verba's seminal study of civic and political culture. Their concept of ‘civic cognition’17 is equivalent to our dependent variable of ‘political interest’. According to Almond and Verba, political interest means ‘following governmental and political affairs and paying attention to politics’, which ‘represent the cognitive component of the civic orientation’.18 In their study they used two straightforward indicators to measure civic cognition: attention to political and governmental affairs in general and attention to major political events and activities such as a campaign in a democratic system. Questions three and four were designed as a supplement to the first two questions. As Inglehart notes, ‘[a] good indicator of political interest is whether or not people discuss politics with others.’19

For the first two questions, not interested at all is coded 1, not quite interested is 2, interested is 3, and very interested is 4. For the last two questions, never is 1, occasionally is 2, very often is 3, and whenever we see each other is 4. These four items were then combined to form an additive index to capture a collective profile of a respondent's political interest level. This index is used as the dependent variable in the multivariate analysis.

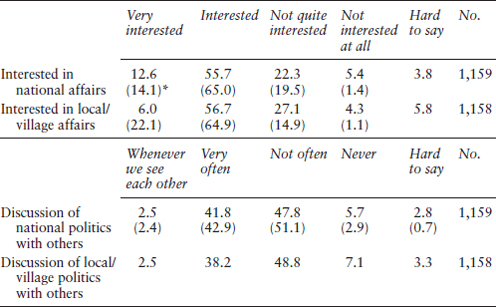

The survey shows that perception of low-level political interest is not the case among peasants in southern Jiangsu. As Table 4.1 shows, about two thirds (close to 70 percent) of the respondents were still interested or very interested in national affairs. This figure is surprisingly close to that found in two mass surveys conducted in the 1990s among Beijing residents. A slightly lower percentage (but still the majority) of the respondents (about 63 percent) cared about local and village affairs. Even though this figure is more than 25 percent lower than that found among urban residents in Beijing, the bottom line is that the majority of peasants in the survey showed some or strong interest in national as well as local and village affairs. These findings seem to contradict the popular perception that most Chinese people, especially most Chinese peasants, are apolitical and do not pay much attention to public affairs and politics.

Table 4.1 Levels of political interest among Jiangsu peasants (%)

Note

*Figures in parentheses are combined findings from surveys conducted in Beijing in 1995 and 1997.

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Even though most respondents were still interested in public affairs, the number of people who talked about politics with others was lower. Fewer than half of the respondents (close to 45 percent) in our survey said they talked about politics often with others (see Table 4.1). This figure, however, is almost identical to that found in the Beijing surveys, indicating that rural residents in Jiangsu are as active as urban residents in Beijing in talking about politics and public affairs. This is remarkable given the stereotype about peasant political apathy in China. A slight lower percentage of the respondents (around 40 percent) discussed local and village affairs often with others.

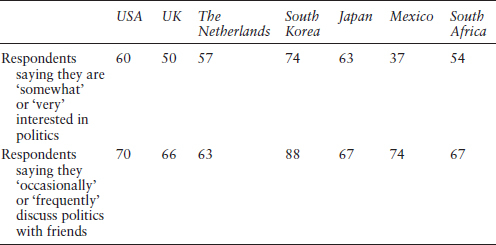

Levels of political interest among the southern Jiangsu rural population are comparable to or higher than those found in some other countries (see Table 4.2). For example, the Jiangsu peasants showed a higher level of political interest than those found in the United States, the United Kingdom, The Netherlands, Japan, Mexico, and South Africa. The figures indicating a high level of political interest among the rural respondents in southern Jiangsu province may not be surprising, considering that there are many national and local issues, such as corruption at various governmental levels, abuse of power by local and village government officials, and government rural policies about which the Chinese peasants are truly concerned. However, it is worth noting that fewer Chinese peasants (as well as Beijing residents, for that matter) talk about politics than people in the other countries mentioned. This probably because China does not have the freedoms that the other countries enjoy, and the Chinese are still somewhat hesitant to talk about politics and national affairs even though the political atmosphere has changed significantly since Mao's time.

Explaining levels of political interest in rural southern Jiangsu province

The association of socio-economic and political factors with one's political interest level has been explicitly studied in western political science literature.20 Chen and Zhong's study on levels of political interest in Beijing showed that a number of demographic, socio-economic and political factors contribute to Beijing residents’ interest in public affairs.21 For example, their study found that middle-aged males, Communist Party members, and people with a better economic standing tended to pay more attention to politics. In addition, their study also revealed a positive relationship between political efficacy and levels of political interest. Finally, they also found that people who were less satisfied with government performance in various policy areas were more interested in politics and public affairs. Drawing upon previous studies on this subject conducted in other countries and China, I will focus on the following demographic, socio-economic and political factors explaining the level of political interest among peasants in southern Jiangsu province: age, gender, education, income, party membership, life satisfaction, and a perceived need for political reform.

Table 4.2 Levels of political interest in USA, UK, The Netherlands, South Korea, Japan, Mexico, and South Africa (%)

Source: 1990 World Values Survey, Ronald Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Countries, pp. 308–9. The actual questions in the survey are: ‘How interested would you say you are in politics?’ and ‘When you get together with your friends, would you say you discuss political matters frequently, occasionally, or never?’.

Age

In western political science literature, a prevailing argument on the age relationship with political interest is that young people tend to show less political interest than the old owing to their preoccupation with other things such as establishing their career and forming a family.22 In their study conducted in Beijing, Chen and Zhong found that this relationship held true among Beijing residents, that is, older people paid more attention to politics than the young, and the age group that paid the closest attention to public affairs was middle-aged. Therefore I hypothesize that age influences levels of political interest among Jiangsu peasants in a positive way, that is, older people tended to pay a higher level of attention to politics and public affairs.

Gender

It has been well documented in western political science literature that there is a gender gap in regard to levels of political interest and political participation. Kent Jennings once noted, ‘a raft of research around the world has demonstrated that, by most standards, men are more politically active than women,’ and such a gap is narrower in more advanced societies and among people of higher socio-economic strata.23 The gap is in part due to the traditional value of women's roles in society and the perception that politics is a ‘man's business’.24

Promoting gender equality has been an official policy in the PRC since the 1950s. Chairman Mao was most vocal in creating equality between men and women in China between the 1950s and the 1970s. Indeed, both men and women were equally mobilized to participate in the various political campaigns launched by Mao during those years. However, gender equality in many areas was never completely achieved during that era due, in part, to deep-rooted Chinese traditional values that favored men over women and encouraged women to be socially passive.25 This situation has not changed in the post-Mao era. As mentioned in Chapter 2, women's status in China has arguably deteriorated during the reform era. Blatant discrimination against women is especially common in regard to employment and in the workplace. Women's roles in Chinese society are still perceived as taking care of the children and family. Women's status is particularly troublesome in rural China.26 Chen and Zhong's survey found that women were less attentive to politics than men in Beijing.27 Therefore, I hypothesize that men were more attentive to politics and public affairs than women were among the southern Jiangsu peasants.

Education

Like age and gender, education is often considered a major factor in affecting levels of political interest and participation.28 There are a number of reasons for the positive relationship between education and interest in politics and public affairs. For one thing, education equips a person with the cognitive capability to receive and digest political information. Education also increases the capacity to understand the personal implications of political events and affairs and one's confidence in one's ability to influence politics if given the opportunity. Empirical studies conducted in China show that education does indeed have an impact on individuals’ attitudes toward public affairs.29 For example, in their study of Beijing residents, Chen and Zhong found that education was positively related to one's level of attention to politics and public affairs.30 In a survey of the Chinese countryside, Jennings also found that peasants with a higher level of education were more active in public affairs.31 I, therefore, hypothesize that level of education, measured by the number of years of formal schooling, positively contributed to one's level of political interest among southern Jiangsu peasants.

Political status

Claiming a membership of 75 million, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is no doubt the world's largest political party. In addition, there are millions of young people who are members of the Chinese Communist Youth League (CYL), an affiliated youth organization of the CCP. One of the requirements for joining the CCP or the CYL is one's political consciousness or level of attention paid to current public affairs. CCP and CYL members are periodically organized in meetings and informed about party and government policies, and discuss political issues. Moreover, party members, who wish to be promoted and climb up the official ladder, have to pay close attention to both national and local political and public affairs. Thus, I expect that CCP and CYL members in this survey showed more interest in politics and public affairs.

Financial and social conditions

If we accept Maslow's theory of the hierarchy of human needs, we should assume that one's interest in politics and public affairs is positively related to one's financial conditions. Voting studies in the West suggest that people of a better economic standing tend to be more active in elections. Verba, Nie, and Kim hinted at another reason why economically better-off people are more likely to be involved in politics and public affairs: they have greater stakes in politics (vested economic interest).32 However, there is another argument suggesting that people with higher incomes are less interested in politics because they are busy making money.33 Some China watchers observe that people with higher incomes in China are preoccupied with grabbing business opportunities and they are less interested in politics and public affairs.34 Another possible reason why people with lower incomes might be more interested in politics and public affairs is that they have more problems and complaints about their poor economic conditions and hope that the government will address their concerns.

In their study of Beijing residents Chen and Zhong did find that the level of political interest was positively related to one's financial conditions.35 Therefore, I hypothesize that peasants with higher income and a higher level of life satisfaction tended to pay more attention to public affairs and be more concerned with political issues in southern Jiangsu province. The main reason is that southern Jiangsu province, being one of the most economically developed rural areas in China, has fewer problems needing urgent government help than the average Chinese countryside. I use two indicators to measure financial and social conditions: income and perceived improvement in economic condition and social status.

Perceived need for political reform

As mentioned in Chapter 2, Chinese reforms since the late 1970s, have been concerned with economic structural changes. Most of the so-called political reforms are primarily administrative or bureaucratic reforms. Even though it seems that most China scholars have recognized that China in the reform era has been transformed from a Maoist totalitarian system to an authoritarian system,36 the fundamentals of the communist political system have remained: the exclusive one-party rule, absolute political power of the CCP in governmental affairs, strict control of party and government personnel by the CCP, complete or near complete control of official media, and the lack of political freedoms and civil liberties. Meaningful and significant political reforms have either been discouraged or postponed in the name of ‘preserving the political stability’ of the country in order to allow economic growth and development to flourish. Yet political reform is still a very much talked about topic in conversations among Chinese people. Many people believe that only meaningful political reform can check or slow down the rampant official corruption and provide genuine political stability in the country. I suspect that one of the reasons why many people pay attention to political or public affairs is because they care for political reforms in China. Therefore, I hypothesize that southern Jiangsu peasants who perceived a need for political reform in China tended to be more interested in politics and public affairs.

Analysis and conclusion

Table 4.3 shows the multi-regression results predicting levels of political interest among southern Jiangsu peasants. Altogether the independent variables explain about 10 percent of the variance in mass political interest in the survey population. Apparently, the basic demographic variables (such as age, gender, and education) do matter in the levels of political interest in the southern Jiangsu peasant population. Specifically, older and better-educated men tended to be more interested in politics and public affairs than the young, the less educated and women. These findings are similar to those found among Beijing residents in the mid-1990s by Chen and Zhong, except for the education factor. They are also consistent with evidence in political interest and participation found in China and other countries.37

As was expected, CCP and CYL members tended to be more interested in politics and public affairs. As mentioned earlier, CCP and CYL members are expected or even required to pay attention to political events and public affairs. Moreover, many of the CCP and CYL members are village cadres whose job is politicking and who also have greater stakes in politics and public affairs.

Table 4.3 also shows that both life satisfaction with material and social status improvement and income are positively related to a person's political interest even though the impact of income is statistically insignificant. The multivariate analysis also shows that a level of political interest is positively related to one's perceived need for political reforms in China. In other words, people who believed that China needed urgent political reforms tended to be more interested in politics and public affairs. The implication is that peasants who are interested in politics and public affairs do care about political reforms in China. Many people believe that Chinese economic reforms have reached a bottleneck stage and only meaningful political reforms can sustain and allow for further economic development. Rampant corruption and social injustice owing to a lack of governmental transparency and official abuse have caused serious social instabilities in China, especially in the countryside. Significant political reforms along the lines of political liberalization and governmental transparency could at least lessen the problems.

Table 4.3 Multivariate analysis of rural political interest in southern Jiangsu province

Independent variables |

Level of political interest |

||

Unstandardized coefficient |

Standard error |

Beta weight |

|

Age |

0.013 |

0.006 |

0.08* |

Gender (female=0; male=1) |

0.704 |

0.141 |

0.17* |

Education |

0.377 |

0.094 |

0.17* |

Income |

0.001 |

0.025 |

0.00 |

Political status (CCP/CYL members=1, non members=0) |

0.521 |

0.173 |

0.12* |

Life satisfaction |

0.223 |

0.054 |

0.14* |

Perceived need for political reforms |

0.214 |

0.081 |

0.09* |

Constant |

6.612* |

0.565 |

|

R squared |

0.11 |

||

Adjusted R squared |

0.10 |

||

N |

740 |

||

Note

*p<.01

Once again, since the survey was conducted in southern Jiangsu province, which is not typical of the vast Chinese countryside, I do not intend to generalize the descriptive findings with regard to levels of political interest to other rural areas of China. Nonetheless, I do believe that the findings from this study are indicative of mass political interest among peasants in more economically developed rural areas of China. First of all, it is very clear from the descriptive findings that Chinese peasants in southern Jiangsu showed a high level of political interest and attention to public affairs. Economic growth and prosperity have not diverted their attention away from politics. The findings put a question mark over the Chinese government's strategy to induce the Chinese population to be apolitical and apathetic by promoting materialism and economic welfare. Moreover, if political interest is an indicator of an individual's potential political activity, the finding of relatively high levels of political interest among peasants in southern Jiangsu province from this survey may imply a great potential for mass political participation and activities in that part of the Chinese countryside.

Second, findings from this study also show that Chinese peasants are not that different from people in other parts of the world, including urban China, as far as the relationships between the level of political interest and some explanatory variables are concerned. The fact that the patterns of interactions between political interest and some determinants: age, education, gender, and perceived economic status, coincide with results from earlier studies in non-Chinese settings and urban China mean that these patterns are not uniquely western and may persist across cultural, political, and geographic divides. Further studies on political interest and its determinants should be carried out in other parts, especially in inland and poorer regions, of the Chinese countryside to gain a better and more comprehensive understanding of the Chinese peasants’ political interest.