Chapter 34

Wisdom-Related Knowledge Across the Life Span

UTE KUNZMANN AND STEFANIE THOMAS

The search for human strengths is a continuous journey with a long history. Since antiquity, one of the guideposts in this search has been the concept of wisdom (e.g., Assmann, 1994; Kekes, 1995). At the core of this concept is the notion of a perfect, perhaps utopian, integration of knowledge and character, mind and virtue.

Societal beliefs suggest that wisdom is an attribute of aging and old age (e.g., Clayton & Birren, 1980; Heckhausen, Dixon, & Baltes, 1989; Sternberg & Jordan, 2005). There are also suggestions in the literature that wisdom and old age are closely intertwined; for example, Erikson postulated in his personality theory of life-span development that generativity and wisdom constitute advanced stages in personality development (Erikson, 1959). Because wisdom has been considered an ideal end point of human development, psychological work on this concept has evolved in the context of life-span developmental psychology and the study of aging (e.g., Baltes, Smith, & Staudinger, 1992).

However, not only life-span and aging researchers value the investigation of human resources; the search for positive human functioning has also been a hallmark of positive psychology (e.g., Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). For at least two reasons, research in this area might benefit from considering wisdom. First, wisdom identifies the highest forms of expertise that humans can acquire. Certainly only few achieve wisdom in its higher form; yet it is those few who hold the key to what humans could be at their best. Second, although it surely takes a lifetime of experience and practice and an ensemble of supportive conditions to acquire wisdom in its higher form, empirical wisdom research suggests that wisdom can be conceptualized as a more-or-less (i.e., quantitative) phenomenon, and, even more to the point, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that even a little wisdom can make a substantial difference in our lives (e.g., Kramer, 2000). Thus, wisdom is a vital component of the three spheres of positive psychology suggested by Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000). That is, wisdom can be considered a positive person characteristic; it involves valuable subjective experiences; and it is a life orientation that contributes to productivity and well-being at the individual, social group, and societal levels.

It deserves note that the acquisition of wisdom during ontogenesis most likely is incompatible with a hedonic life orientation and a predominantly pleasurable and sheltered life (Kunzmann & Baltes, 2003a, 2003b; Staudinger & Kunzmann, 2005). Given their interest in maximizing a common good, wiser people are likely to partake in behaviors that contribute to, rather than consume, resources. In addition, an interest in understanding the significance and deeper meaning of phenomena, including the blending of developmental gains and losses, most likely is linked to emotional complexity and a tolerance for negative affective experiences (Labouvie-Vief, 1990, 2003) or to what has been called “constructive melancholy” (Baltes, 1997b).

Defining Wisdom

Because of its enormous cultural and historical heritage, a comprehensive psychological definition and operationalization of wisdom is extremely difficult, if not impossible. At least three types of conceptualizations of wisdom can be identified in the literature. In these conceptualizations, wisdom has been defined as a part of personality development in adulthood (e.g., Ardelt, 2003; Erikson, 1959; Wink & Helson, 1997), a form of postformal dialectic thinking (e.g., Kramer, 1990, 2000; Labouvie-Vief, 1990), and an expanded form of intelligence (e.g., Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Sternberg, 1998).

Despite their different origins, these three types of conceptualizations share several theoretical ideas. A first is that wisdom is different from other person characteristics in that it is integrative and involves cognitive, affective, and motivational elements. Second, wisdom is an ideal: Many people may strive for wisdom but only few, if any, will ever become truly wise. Third, wisdom sets high behavioral standards; it guides a person's behavior in ways that simultaneously optimize this person's own potential and that of fellow mortals (see also Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Sternberg, 1998). We return to these three ideas in the course of this chapter as we discuss the Berlin wisdom paradigm and the research initiated by this paradigm.

The Berlin Wisdom Paradigm

Informed by cultural-historical work, in the Berlin wisdom paradigm, wisdom has been defined as expert knowledge about fundamental questions regarding the meaning and conduct of life (e.g., Baltes & Kunzmann, 2003; Baltes & Smith, 1990; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000). Five criteria serve to describe this type of expert knowledge. The first two general, basic criteria (factual and procedural knowledge) are characteristic of all types of expertise. Applied to wisdom-related expertise, these criteria are rich factual knowledge about human nature and the life course and rich procedural knowledge about ways of dealing with fundamental questions about the meaning and conduct of life. The following three meta-criteria are considered to be specific for wisdom-related expertise: life-span contextualism, value relativism and tolerance, and an awareness and management of uncertainty. Life-span contextualism refers to a deep understanding about the many contexts of the given life problem, how these contexts are interrelated, and how they change over time. Value relativism and tolerance describes the acknowledgment of individual and cultural differences in values and life priorities. A person with high wisdom-related knowledge tolerates and even embraces the various and often opposing viewpoints on a life problem and has available heuristics on how to deal with them in a balanced fashion. Finally, the awareness and management of uncertainty refers to an understanding that life decisions, evaluations, or plans will never be free of uncertainty, but must be made as well as one can and not be avoided in a resigning manner. Expert knowledge about the meaning and conduct of life is said to approach wisdom, if it meets all five criteria.

As this definition of wisdom suggests, wisdom is neither technical nor intellectual knowledge. On the contrary, at the core of this body of knowledge is a deep understanding of human nature and the close intertwinement of the three faculties of the mind: cognition, emotion, and motivation. For example, outstanding knowledge about life's uncertainties and ways of dealing with them requires knowledge about the emotions that are associated with uncertainty. Value relativism and tolerance reflects a deep understanding about the causes and dynamics of human motives and goals. Life-span contextualism includes knowledge about normative and idiographic events that not only shape a person's future life but are also a source of deep emotional experiences (e.g., birth of a child, death of loved ones).

In the traditional empirical paradigm, participants read short vignettes about difficult life problems and think aloud about these problems. For example, a problem related to life review might be, “In reflecting over their lives, people sometimes realize that they have not achieved what they had once planned to achieve. What could they do and consider?” Another dilemma reads, “Somebody receives a phone call from a good friend. He or she says that he or she cannot go on anymore and has decided to commit suicide. What could one consider and do?” Trained raters evaluate responses to the Berlin wisdom tasks by using the five criteria that were specified as defining wisdom-related knowledge. As demonstrated in our past research, the assessment of wisdom-related knowledge on the basis of these criteria exhibits satisfactory reliability and validity (for reviews see Baltes & Kunzmann, 2003; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Staudinger & Glück, 2011).

Personal Versus General Wisdom

As a conceptual refinement, Staudinger and colleagues have recently suggested a differentiation between general wisdom (i.e., insight into life in a generalized form that transcends self-related experience and evaluation) and personal wisdom (i.e., insight in to one's own life and self-related experiences; e.g., Staudinger & Glück, 2011). According to the authors, the traditional Berlin wisdom tasks that ask for knowledge about fundamental life problems in a largely decontextualized and generalized fashion are well-suited to assess general wisdom. Other expertise-based wisdom approaches such as Sternberg's balance theory of wisdom or neo-Piagetian conceptions of wisdom as postformal thought may be assigned to the approach of assessing general wisdom as well. By contrast, the idea of personal wisdom is closely linked to past approaches that have considered wisdom as a stage of personality development (e.g., Ardelt, 2003; Helson & Wink, 1987). Whereas approaches that conceptualize wisdom as part of personality have used self-report measures to assess the wise personality, Staudinger and colleagues developed a measure of personal wisdom that is in the tradition of performance-based testing (for a review of different approaches to assess wisdom, see Kunzmann & Stange, 2007). More specifically, participants are asked to think aloud about the self and the resulting think-aloud protocols are assessed on the basis of wisdom criteria that are similarly structured as the traditional Berlin wisdom criteria (e.g., Mickler & Staudinger, 2008). More specifically, two basic criteria are self-knowledge (the insight into oneself) and growth and self-regulation (heuristics to deal with challenges); three meta-criteria are interrelating the self (the insight into possible causes of one's own behavior), self-relativism (distance from the self), and tolerance of ambiguity (to recognize and manage uncertainties in one's own life).

For several reasons, personal wisdom and general wisdom do not necessarily coincide. For example, highly intellectual individuals who are interested in questions regarding human nature and the life course but who have had a difficult personal life history may be able to give valuable wise advice to others or to think about uncertain and difficult questions related to the meaning and conduct of life on a general and abstract level, but they may have a particularly hard time making sense of their own authentic experiences and feelings and, thus, gaining insight into what makes their own lives difficult. Other individuals, perhaps the majority of individuals, may have the personal requirements to acquire some wisdom as it pertains to their own life experiences and problems, but they may not be able or motivated to reflect about human nature on a more abstract level and to generalize and integrate their self-related insights what would bring them closer to wisdom in its ideal and higher form.

On a more general level, we believe that a conceptualization of wisdom as a concept that encompasses several distinct forms makes intuitive sense as soon as one considers individuals rather than cultural products as carriers of wisdom (Baltes & Kunzmann, 2004). Human beings are fallible (Baltes, 1997a), and it is impossible to nominate a truly wise individual, that is, an individual with only vices and no weaknesses. Empirical work provided by Mickler and Staudinger (2008) is consistent with this idea in that it suggests that only few individuals are high on both general wisdom and personal wisdom. These two types of wisdom are highly distinct and show only a low positive correlation.

The Assessment of Wisdom-Related Knowledge via Real-Life Rather Than Hypothetical Problems

Another recent refinement of the traditional Berlin paradigm has been the development of new wisdom tasks that present real-life problems rather than hypothetical dilemmas (Thomas & Kunzmann, 2013). With this approach, a major goal has been to address the concern that the traditional Berlin wisdom tasks are too cognitive in that they present life dilemmas in a highly abstract and condensed fashion so that the dilemmas hardly evoke any emotions and may not even require a deep understanding of emotions in order to be dealt with wisely (e.g., Ardelt, 2004; Redzanowski & Glück, 2013).

To address this concern and develop wisdom tasks that present real-life life problems, we have produced short film clips of couples as they discuss a real, long-lasting, and serious conflict in their marriage. Participants are asked to carefully watch a film and to then think aloud about what the couple might want to think and do to go about solving their problem. The development of these film-based tasks involved a multiple-step validation procedure, ensuring that the spouses, two experts in marital interaction research, and a sample of lay people consistently rated the films as highly authentic, the problems as serious and complex, and the couples' emotional distress as extremely high (Thomas, 2012; Thomas & Kunzmann, 2013). A first study with a heterogeneous sample of almost 200 adults spanning the adult life span provided initial support for the idea that these tasks elicit greater emotional reactions than the traditional hypothetical vignettes. Interestingly, however, the new film-based tasks and the traditional vignette-based tasks did not differ in terms of the degree to which they elicited concrete and practical rather than abstract and theoretical knowledge (Thomas, 2012).

Together our findings suggest that it is worth the effort to develop wisdom tasks that present real-life life dilemmas in more context-rich and natural ways than is possible via the traditional Berlin text vignettes. Our film-based tasks appear to be particularly well suited to elicit a wide range of emotions and, thus, to investigate the dynamic between emotional and cognitive processes inherent in wisdom.

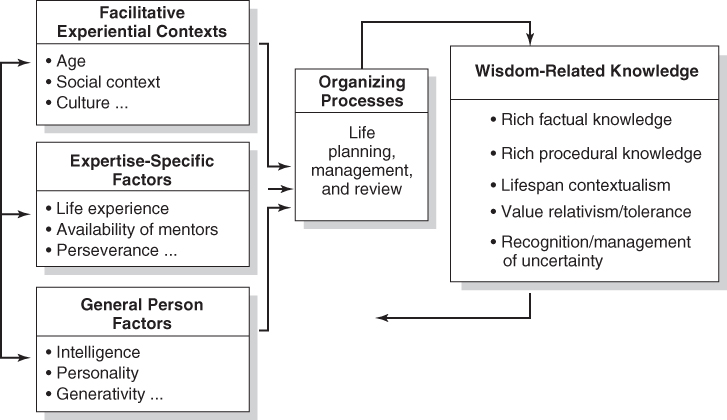

The Development of Wisdom-Related Knowledge: Theoretical Ideas

The conceptualization of wisdom as expertise suggests that wisdom can only be acquired through an extended and intensive process of learning and practice. According to the Berlin wisdom model (see Figure 34.1), this process requires multiple factors that can be subsumed under (a) facilitative experiential contexts, as determined for example by a person's age, social context, or culture; (b) expertise-specific factors such as life experience, professional practice, or receiving and providing mentorship; and (c) more general person-related factors such a certain degree of academic intelligence, certain personality traits, emotional dispositions, and motivational orientations. These three types of resources are thought to influence the ways in which individuals actually plan, manage, and evaluate important events in life (e.g., how they deal with a particular problem and how they evaluate the costs and benefits of the different solutions to it). These organizing processes are at the core of the Berlin model and are meant to highlight that wisdom-related knowledge can only be gained though accumulated experience and dealing with important and uncertain questions regarding the meaning and conduct of life. In this sense, wisdom-related knowledge has been thought to be “own” experience based; it cannot be acquired vicariously (e.g., by reading books) or by direct instruction (see also Sternberg, 1998).

Figure 34.1 Developmental of wisdom: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences

Note. The acquisition of wisdom-related knowledge is assumed to be dependent on an effective coalition of life-context, expertise-specific, and general person-related factors.

Three aspects of the model deserve special note. First, there most likely are several paths leading to wisdom rather than only one. Put differently, similar levels of wisdom may result from different combinations of facilitative resources and organizational processes. If a certain coalition of facilitative factors and processes is present, some individuals continue a developmental trajectory toward higher levels of wisdom-related knowledge. Second, the facilitating factors (e.g., a certain family background, critical life events, professional practice, or societal transitions) are thought to interact in complex additive, compensatory, and time-lagged ways. Third, wisdom-related knowledge is considered an outcome and precursor of the resources and organizational processes related to the meaning and conduct of life. For example, openness to new experience and wisdom-related knowledge most likely mutually influence each other.

Recently, Glück and colleagues have presented a developmental model of personal wisdom, the so-called MORE model (e.g., Glück & Bluck, 2013). Consistent with the Berlin wisdom model, the MORE model states that wisdom can only be gained through exposure to existential challenges and crises. Of course, it is not the amount of experience with critical life events per se that is thought to lead to wise thought and action, rather the ways experiences are perceived and dealt with. The acronym MORE refers to the person-related resources that are thought to support the development of wisdom: mastery, openness to experience, reflexivity, and empathy, including emotion regulation. According to the authors, a sense of mastery helps individuals going through hard times, trusting their own abilities and strengths while recognizing that many things in life are uncertain and out of personal control. Openness to experience facilitates tolerating life's challenges and enhances the motivation to learn from them. Reflexivity helps to recognize the multiple sides and meanings of a problem, including the critical questioning of one's own preferred ways of interpreting events. Finally, the authors elaborate two emotional competences that support the complex process of wisdom attainment. Empathy facilitates attention and emotional responsiveness to others' problems and concerns, while emotion regulatory skills help the wise advice giver to not become overwhelmed by others' problems, and it supports the constructive management of own and others' emotions in the face of serious and existential problems.

The two theoretical models about the ontogenesis of wisdom reviewed earlier obviously have many ideas in common. One aspect that is distinct refers to broadness of the models. More specifically, the MORE model focuses on the person-related resources for the attainment of wisdom and is less concerned with social and contextual factors that also contribute to wisdom. In this sense, the Berlin model is more comprehensive; it specifies contextual factors on micro and macro levels as one set of factors that is essential in the development of wisdom-related knowledge. From a life-span developmental perspective, one important implication of both models is the idea that, at least during adulthood, becoming older is neither sufficient nor necessary to develop higher levels of wisdom knowledge.

Age Differences in Wisdom-Related Knowledge: Empirical Evidence

Consistent with the two theoretical models of the ontogenesis of wisdom, in several cross-sectional studies utilizing the Berlin wisdom tasks, the association between age and wisdom-related knowledge was nonsignificant and virtually zero (reviews: Staudinger, 1999; Staudinger & Glück, 2011). This evidence is not surprising given that the way to higher wisdom is resource demanding and requires a deliberate, intensive, and extended dealing with difficult and uncertain life problems. In addition, a range of supportive person-related and contextual factors is likely involved in the development of wisdom. Some wisdom-facilitating resources have been shown to decline with age, others remain stable, and yet others increase, suggesting a zero-sum game and age-related stability in overall wisdom-related knowledge (e.g., Staudinger, 1999). As reviewed next, a differentiation between distinct forms of wisdom even suggests that there may be some facets of wisdom-related knowledge that decline with age. In addition, there is reason to believe that the development of wisdom-related knowledge may be better described as a process of sequential gain and loss rather than a process of cumulative growth.

Personal Versus General Wisdom: Multidirectional Age Differences?

In a cross-sectional study with a sample that covered most of the adult life span, Staudinger and colleagues recently found that, consistent with past cross-sectional evidence, general wisdom remained stable across the age groups studied; however, personal wisdom, as assessed by criteria such as self-relativism and tolerance of ambiguity, declined with age (Mickler & Staudinger, 2008). The authors have argued that this age-related decline may be associated with parallel age-related declines in openness to new experience (e.g., Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2011), making it increasingly unlikely that older individuals have to test previously established self-related insights against new evidence—a prerequisite to developing higher levels of personal wisdom. On a more general level, one could describe the aging process as one that involves an increase in social, cognitive, and health-related losses that ultimately makes it less and less likely that older adults come to make new experiences and question their previously proven and familiar ways of seeing the self and others. Adopting an environmental perspective, one could also argue that our society is still structured in a way that prevents older adults from making new and varied experiences with the outer world.

Before accepting this and related ideas, however, it certainly remains to be seen if the currently cross-sectional evidence for an age-related deficit in personal wisdom will be replicated in the context of longitudinal data. For example, it could well be that the decrease in personal wisdom across the age groups studied is at least partly the result of cohort rather than age effects, given that the members of earlier cohorts most likely are less used to talking and thinking about the self than later cohorts.

The Ontogenesis of Wisdom: A Sequence of Gain and Loss?

Most people seem to be aware that not everyone develops wisdom in old age and that wisdom—in a domain-general and ideal sense—may be a rare phenomenon regardless of age. And yet, it is still possible that many adults can gain some wisdom about some problems, namely, the problems that are particularly salient in their current life (Thomas & Kunzmann, 2013). Typically, the problems an individual has a high need to deal with and solve are at least partly influenced by this individual's age (Baltes, 1987; Erikson, 1968). For example, old age has been described as a period of loss during which individuals need to let go of many goals and find meaning in their lives as lived. Eventually because of their greater exposure to the theme of loss, older adults may be more likely to gain wisdom-related knowledge about the problems and challenges that surround this theme than their younger counterparts. This does not necessarily mean, however, that older adults generally have greater wisdom-related knowledge than younger people. There may be problem areas that are more familiar to young adults than to older adults and that may elicit greater wisdom-related knowledge in the young. In a recent study, we provided the first evidence for the idea that conflict in intimate relationships may be such a domain (Thomas & Kunzmann, 2013). In a study with 200 adults spanning the adult life span, we found that wisdom-related knowledge about marital conflict, a problem that is way more common in young adulthood than in old age (e.g., Birditt, Fingerman, & Almeida, 2005), was highest in the youngest age group studied (20 to 29 years of age) and linearly decreased across the subsequent age groups. A follow-up analysis revealed that young adults' greater exposure to serious conflicts and greater willingness to actively engage in conflicts partly accounted for the age differences in wisdom-related knowledge about marital conflict. In contrast, wisdom-related knowledge about suicide, a nonnormative life event that is not particularly likely to occur at a specific age during the adult life span, remained stable across age groups.

Taken together, this evidence is consistent with the idea that young adults can be wiser than older adults in some domains and that the development of wisdom-related knowledge may not be cumulative. Just as any type of knowledge, wisdom-related knowledge about a particular type of problem may only be available if it is regularly used (Förster, Liberman, & Higgins, 2005; Jarvis, 1987). In this sense, the development of wisdom may be described as a sequential process of gain and loss: most individuals are likely to gain a certain degree of wisdom-related knowledge about the problems that are highly salient in their current life; however, this knowledge may become less available and may even vanish if it is not adaptive anymore (i.e., if it is not used because it refers to developmental tasks and problems that are not salient anymore). Consistent evidence was reported by Glück and colleagues (Glück, Bluck, Baron, & McAdams, 2005; König & Glück, 2012). The authors asked their participants from different age groups to report situations in which they themselves thought, said, or did something wise. These situations were later classified according to the form of wisdom that they primarily require. There were systematic age differences in what people considered as instances of wisdom in their own life; and, more to the point, these age differences reflected the developmental tasks of each age group.

Summary

Taken together, past evidence from different laboratories has supported the view that wisdom does not automatically come with age. We all can learn lessons about the challenges and problems that are part of life regardless of whether we are in our 20s or 60s. Given that individuals have limited resources, however, they have to be selective and can neither acquire wisdom-related knowledge in all possible life domains nor maintain wisdom-related knowledge that they had previously acquired if this knowledge has lost its relevance. Only for very few individuals, and if a rare constellation of facilitating factors and processes is present, domain-specific wisdom-related knowledge may be a stepping-stone to wisdom-related knowledge in a more generalized sense that transcends a particular problem type. Seen in this light, the absence of a normative increase in wisdom-related knowledge with age, which the current cross-sectional evidence for a nonsignificant relationship between age and wisdom-related knowledge suggests, is not surprising. As long as wisdom-related knowledge is assessed by age-neutral and rather general life dilemmas, more domain-specific gains and losses in wisdom-related knowledge cannot be made visible. Notably, these ideas are consistent with several models of successful life-span development, particularly the model of selection, optimization, and compensation proposed by Baltes and his colleagues (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Freund & Baltes, 2002).

Wisdom as the Successful Integration of Cognition and Emotion

The definition of wisdom as an expert knowledge system about the meaning and conduct of life may suggest to some that the Berlin wisdom model is too cognitive and ignores emotional competencies—that are also central elements of wisdom. However, from a life-span developmental point of view, certain emotional experiences and dispositions have been considered to be fundamental to the acquisition of wisdom-related knowledge. In addition, the effectiveness of wisdom-facilitating factors that are not primarily emotional in nature (e.g., stimulating social environments or the availability of a high-quality education) not only depends on a person's intellectual functioning (e.g., ability to learn new things, abstract reasoning, or accuracy of information processing) but also on this person's social and affective competencies and dispositions (e.g., level of emotional balance, impulsivity, neuroticism, or social competence).

It is also likely that the expression of wisdom-related knowledge in a particular situation is moderated by certain emotional dispositions and competencies (e.g., Kunzmann & Baltes, 2005). An advice giver who is not able or willing to imagine how a person in need feels, for example, is not likely to make an effort and engage in wisdom-related thinking that would involve careful and detailed analysis of the advice seeker's problem, the weighting and moderation of different parts of the situation, and the consideration of multiple views. Similarly, during a mutual conflict with another person, being able to imagine how this person feels or how one would feel in the other's place may be one stepping-stone to value tolerance and a cooperative approach typical of wisdom.

At the same time, however, one can easily think of emotional reactions to difficult and potentially stressful situations that are likely to hinder a wisdom-like approach. Examples are self-centered feelings that indicate personal distress, especially if these negative feelings are intense and long lasting. Two examples: If people are not able or willing to control their feelings of anger, contempt, or jealousy, they are likely to hurt or enrage others rather than come up with a wise solution to the problem at hand. Strong and chronic feelings of anxiety might inhibit wisdom-related thinking, which requires distance from the immediate situation, balance, and elaboration. It is in this sense that cold cognition and hot emotion have been described as two forces that antagonize one another (see Keltner & Gross, 1999).

Taken together, when considering the adaptive value of (negative) emotions in the face of existential problems, it certainly is important to differentiate two dimensions referring to the self-centeredness of emotions (self-related vs. empathy-related) and the intensity of emotions (low vs. moderate vs. high).

Certainly, the links between emotion and cognition can take any direction. The idea that certain emotions hinder or facilitate the activation of wisdom-related knowledge and behavior may be less popular in the wisdom literature than the notion that it is wisdom that regulates a person's emotional experiences and reactions. In this vein, wisdom researchers have conceptualized wisdom as a resource or personal characteristic that encourages the experiencing of certain positive emotions such as sympathy and compassionate love, and decreases the experience of negative emotions (e.g., feelings of hostility, contempt, or personal distress; e.g., Ardelt, 2003). Although we are sympathetic to the idea that wisdom can involve emotional down-regulation in the face of difficult problems, in our own work we proceed from the idea that wisdom does not involve the total absence of negative emotions. Rather, in the face of a difficult and uncertain problem, it should facilitate emotional responses of moderate intensity (neither extremely high nor extremely low) through a balancing of two opposing emotion regulatory styles: emotional distancing and emotional responsiveness (for more details see later discussion).

Wisdom as the Successful Integration of Cognition and Motivation

Does wisdom-related knowledge guide a person's behaviors in grappling with difficult problems and interacting with others? How do people use their wisdom-related knowledge in everyday life, and what is the motivational orientation that goes hand in hand with this type of knowledge? If wisdom-related knowledge were an end in itself and had no correspondence with what an individual wants and does in his or her life, it could hardly be considered a resource. This is at least the idea that was proposed by several modern philosophers influenced by the tradition of early Greek philosophy. This group of researchers has argued that wisdom as knowledge is closely linked to wisdom as manifested in an individual's everyday behavior. In this tradition, wisdom has been thought to be a resource facilitating behavior aimed at promoting a good life at both an individual and a societal level. For example, Ryan (1996) defined a wise person as follows: “A person S is wise if and only if (1) S is a free agent, (2) S knows how to live well, (3) S lives well, and (4) S's living well is caused by S's knowledge of how to live well” (p. 241). Kekes (1983) wrote, “Wisdom is a character trait intimately connected with self-direction. The more wisdom a person has the more likely it is he will succeed in living a good life” (p. 277).

Notably, a good life is not linked exclusively to self-realization and personal happiness but encompasses more, namely, the well-being of others. In this sense, Kekes (1995) has stressed that wisdom is knowledge about ways of developing oneself not only without violating others' rights but also with co-producing resources for others to develop. Thus, in these philosophical conceptualizations, a central characteristic of a wise person is the ability to translate knowledge into action geared toward the development of oneself and others.

Psychological wisdom researchers have begun to respond to the longstanding notion that wisdom-related knowledge requires and reflects certain motivational tendencies, which in turn shape the use of wisdom-related knowledge and guide its application in daily life (e.g., Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Kramer, 2000; Sternberg, 1998). Notably, however, wise persons have been described as being primarily concerned with other people's well-being rather than with their own (e.g., Ardelt, 2003; Holliday & Chandler, 1986). Consistent with this view, Helson and Srivastava (2002) provided evidence that wise persons tend to be benevolent, compassionate, caring, and interested in helping others. The idea that wisdom is different from prosocial behavior in that it involves a joint consideration of self- and other-related interests, however, has rarely been tested empirically. In the following section, we will discuss empirical studies from our lab that can be considered a first step in demonstrating that wisdom is inherently of an intra- and interpersonal nature.

Emotional-Motivational Elements of Wisdom: Empirical Evidence

In the following, we will review three empirical studies that examined various person characteristics as correlates of wisdom-related knowledge. By highlighting the role of wisdom-related knowledge in certain personality characteristics (e.g., openness to new experiences or psychological mindedness), affective experiences, value orientations, and preferences for certain conflict-management strategies, we aim to broaden our understanding of the concept of wisdom and the behavioral sphere in which it is embedded.

Wisdom: Intelligence, Personality, and Social-Cognitive Style?

To test parts of the Berlin developmental model of wisdom-related knowledge (see Figure 34.1), Staudinger, Lopez, and Baltes (1997) investigated three general person factors as correlates of wisdom-related knowledge. These factors were test intelligence, personality traits, and several facets of social-cognitive style. A central goal of this study was to empirically demonstrate that intelligence, as assessed by traditional psychometric tests, would be a relatively weak predictor of wisdom-related knowledge, whereas personality traits and especially social-cognitive style would be more important. This prediction was tested in a study with 125 adults. In a first individual interview session, wisdom-related knowledge was assessed by the traditional Berlin wisdom tasks. During a second session, the authors employed 33 measures to assess multiple indicators of intelligence (e.g., speed of information processing, logical thinking, practical knowledge), personality (e.g., neuroticism, extraversion, openness to new experiences), and social-cognitive style (e.g., social intelligence, creativity, interest in others' needs). Not all indicators were significant predictors. For example, unrelated to wisdom-related knowledge were speed of information processing and four of the five classic personality traits (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness); only openness to experience was positively related to wisdom-related knowledge. When analyzed separately, the significant intelligence measures accounted for 15% of the variance in wisdom-related knowledge, social-cognitive style accounted for 35% of the variance, and personality for 23%. The simultaneous analyses of all three sets of predictors in hierarchical multiple regression analyses revealed that the unique prediction of intelligence and personality was small (i.e., 2% each), whereas indicators of social-cognitive style contributed a larger share of unique variance, namely, 15%.

Together this evidence clearly supports the notion that wisdom-related knowledge, as operationalized via the Berlin wisdom tasks, is not simply a variant of intelligence. It deserves special note that neither academic intelligence nor basic personality dispositions such as neuroticism or extraversion show substantial relationships to wisdom-related knowledge. Our general life orientation, cognitive style, and social preferences—all aspects that individuals can and do shape during adult development—seem to be more closely related to wisdom-related knowledge.

Emotional and Motivational Dispositions as Correlates of Wisdom as Knowledge

Extending the study reviewed earlier, Kunzmann and Baltes (2003b) provided further evidence for the idea that wisdom-related knowledge is associated with certain motivational and emotional dispositions. These dispositions referred to affective experiences (pleasantness, interest/involvement, and negative affect), value orientations (pleasurable life, personal growth, insight, well-being of friends, environmental protection, societal engagement), and preferred modes of conflict management (dominance, submission, avoidance, cooperation). By highlighting the relations between wisdom-related knowledge and these indicators, our aim was to broaden our understanding of the emotional-motivational side of wisdom-related knowledge.

The main predictions were based on the notion that wisdom-related knowledge requires and reflects a joint concern for developing one's own and others' potential (see also Sternberg, 1998). In contrast, a predominant search for self-centered pleasure and comfort should not be associated with wisdom. Accordingly, people high on wisdom-related knowledge should report (a) an affective structure that is positive but process- and environment-oriented rather than evaluative and self-centered; (b) a profile of values that is oriented toward personal growth, insight, and the well-being of others rather than a pleasurable and comfortable life; and (c) a cooperative approach to managing interpersonal conflicts rather than a dominant, submissive, or avoidant style.

The findings were consistent with these predictions. People with high levels of wisdom-related knowledge reported that they less frequently experience self-centered pleasant feelings (e.g., happiness, amusement) but more frequently experience process-oriented and environment-centered positive emotions (e.g., interest, inspiration). People with higher levels of wisdom-related knowledge also reported less preference for values revolving around a pleasurable and comfortable life. Instead, they reported preferring self-oriented values such as personal growth and insight as well as a preference for other-oriented values related to environmental protection, societal engagement, and the well-being of friends. Finally, people with high levels of wisdom-related knowledge showed less preference for conflict-management strategies that reflect either a one-sided concern with one's own interest (i.e., dominance), a one-sided concern with others' interests (i.e., submission), or no concern at all (i.e., avoidance). As predicted, they preferred a cooperative approach reflecting a joint concern for one's own and the opponent's interests.

Together, the evidence clearly supports the notion that wisdom-related knowledge is linked to certain motivational orientations (i.e., a joint concern for developing one's own potential and that of others) and affective dispositions (i.e., the tendency to experience positive, environment-oriented emotions rather than evaluative, self-centered feelings such as happiness or negative feelings such as anger, fear, sadness).

Emotional Reactions to Fundamental Life Problems: Wisdom Makes a Difference

A main goal of a third study that we recently completed in our laboratory was to provide evidence for the idea that wisdom-related knowledge facilitates a balanced emotion regulatory style that helps individuals at any age to react to negative emotion inducing events in a moderate fashion (Kunzmann & Thomas, in preparation). More specifically, we proceeded from the idea that individuals with high wisdom-related knowledge will neither become overwhelmed by existential problems nor will they remain emotionally unaffected because wisdom-related knowledge facilitates a balancing of two opposing emotion regulatory principles, emotional distance and emotional responsiveness.

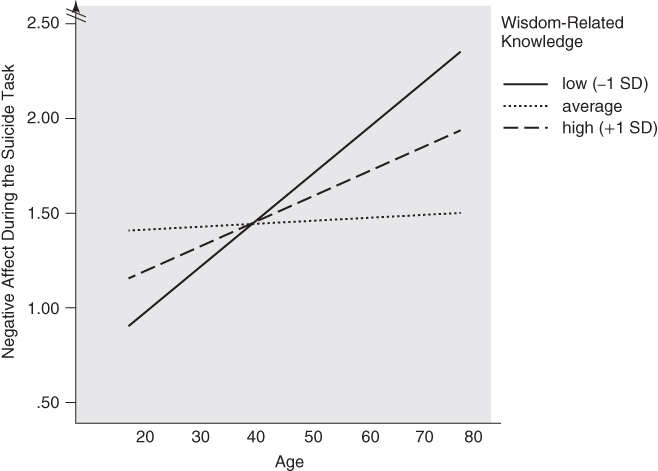

We began to test this idea in a study with almost 200 participants spanning the adult life span. As to the procedure, our participants were first presented with a traditional wisdom task (i.e., the suicide task) and asked to think about it silently for 2 minutes. They were then instructed to report their feelings during this silent phase on an emotion adjective list covering 18 positive and negative emotions. Finally, they thought aloud about the task and their think-aloud responses were later coded according to the three Berlin wisdom meta-criteria. Given that we were the first to assess emotional reactions to a traditional wisdom task, it may be worthwhile to report that the task elicited emotional reactions of moderate intensity, especially shock, sadness, and fear. This may be surprising given that the task presents the suicide problem in a highly abstract and decontextualized way. However, most of the participants were able to relate to the problem while thinking about it. In addition, in the entire sample, the association between wisdom-related knowledge and negative emotional reactivity was nonsignificant. At first sight, this evidence speaks against the idea that wisdom-related knowledge makes a difference for an individual's emotional reactions. This conclusion may be unwarranted, however, given that the main finding of this study was that age differences in the intensity of emotional reactions were dependent on an individual's level of wisdom-related knowledge. Our follow-up analyses revealed that the emotional reactions of people with high wisdom-related knowledge were of moderate size, independent of whether they were young or old and, thus, more or less concerned with an existential life problem related to death and dying. By contrast, the emotional reactions of people with low wisdom-related knowledge were dependent on age and, thus, arguably, by the degree to which the problem at hand was self-relevant: Older adults, for whom the task was highly self-relevant, reported the highest level of negative emotional reactivity, most likely because they had difficulties contextualizing the problem and considering it on an abstract level of analyses that would have helped them down-regulate their negative feelings; younger adults, for whom the task was of little self-relevance, reported the lowest level of negative reactivity, most likely because they had difficulties understanding the significance and implications of a problem that was not particularly self-relevant (the findings are graphically depicted in Figure 34.2).

Figure 34.2 Age differences in negative emotional reactivity are dependent on wisdom-related knowledge

Notes. To test our predictions regarding the effects of age and wisdom-related knowledge on negative emotional reactivity, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. The dependent variable referred to the level of negative affect during the suicide task. As to the independent variables, in the first step, negative affect experienced during a baseline period served as a predictor. In the second step, the main effects of age and wisdom-related knowledge were entered into the regression equation. In the third step, the interaction term (i.e., age by wisdom) were tested for significance. There was a main effect of age (ß = 21, t = 2.89, p < .01). The main effect of wisdom was nonsignificant (ß = –.05, t = .75). The interaction between age and wisdom became significant (ß = –.16, t = –2.18, p < .05).

Notably, the findings from this study oppose the view that individuals with high levels of wisdom-related knowledge generally are emotionally distant and detached (e.g., Erikson, 1959; Kross & Grossmann, 2012). Rather, wisdom-related knowledge appears to involve a balancing between emotional distance and emotional responsiveness, and, thus, emotional reactions of moderate intensity.

Conclusion

Given the emotional and motivational benefits that come with wisdom-related knowledge, the question arises as to whether this type of knowledge can be taught in school (e.g., Sternberg, 2001) or in contexts of professional training and practice (e.g., Küpers & Pauleen, 2013). At one time or another in their career, most professionals have to struggle with one or more of the following questions: How can I coordinate my professional career and family development, balance my work load and leisure time, get along with my colleagues, identify my interests, and pursue those interests cooperatively? From a leadership perspective, one might add questions such as, How can I maximize a common good rather than optimize the interests of certain individuals or small groups of individuals, get employees involved and motivated, develop and communicate a useful and inspiring vision, and coordinate the long-term and short-term goals of my cooperation or institution?

What the problems mentioned here have in common is that they are fundamental, complex, and uncertain; they are poorly defined, have multiple yet unknown solutions, and require coordinating multiple and often conflicting interests within and among individuals. This is precisely why professional knowledge in the narrow sense is typically insufficient to deal with these problems effectively. In contrast, wisdom-related knowledge, as we have defined this concept, is designed to deal especially with problems of this kind. As emphasized earlier, wisdom-related knowledge encourages us to embed problems in temporal contexts (past, present, future) and thematic contexts (e.g., family, friends, work) and to consider problems from a broad perspective rather than in isolation. Wisdom-related knowledge also helps to acknowledge the relativity of individual and culturally shared values and to take other values and life priorities into account when thinking about possible problem solutions. Finally, wisdom-related knowledge facilitates an understanding of what one knows and does not know, as well as what can be known and cannot be known at a given time and place. Perhaps even more important, a small but growing body of evidence suggests that how we think and what we know influences how we feel and act. Wisdom-related knowledge facilitates a balancing of one's own interests and those of others, including institutional interests. It is incompatible with impulsive, mindless, or immoral judgments and rather facilitates behaviors that can maximize what has been called the common good. Participating in training programs on wisdom will surely inspire some people to deal in new and constructive ways with the difficulties of life that none of us can avoid.

Summary Points

- Several promising definitions of wisdom have been proposed in the psychological literature. The Berlin wisdom model focuses on one facet of wisdom, that is, knowledge. On the most general level, wisdom-related knowledge has been defined as deep and broad knowledge about difficult and uncertain problems related to the meaning and conduct of life. This type of knowledge can be specified on the basis of five wisdom criteria, including life-span contextualism, value relativism and tolerance, and uncertainty acknowledgement and management.

- The way to higher wisdom-related knowledge is resource demanding and requires a deliberate, intensive, and extended dealing with difficult and uncertain life problems. This process can be facilitated or hindered by a number of person-related and contextual factors. As a consequence, age per se is not sufficient for the acquisition and further development of wisdom-related knowledge.

- There is reason to believe that becoming older may not even be necessary for wisdom-related knowledge to develop during adulthood and old age. Some wisdom-facilitating resources have been shown to decline with age, others remain stable, and yet others increase, suggesting a zero-sum game and age-related stability in overall wisdom-related knowledge. Furthermore, a conceptualization of wisdom-related knowledge as domain-specific allows studying the idea that wisdom-related knowledge may not be constant across the adult life span, but better described as a process of sequential gain and loss. Given that all humans have limited resources, they may selectively acquire and maintain wisdom-related knowledge about only those life problems that are currently most salient. As a consequence, there may be problems that elicit greater wisdom-related knowledge in younger adults (i.e., problems that are typical and salient in young adulthood), whereas other problems elicit greater wisdom-related knowledge in older adults (i.e., problems that are more typical and salient in old age).

- Even if the way to higher wisdom is cumbersome and most adults only acquire some wisdom about some problems, it is worth the effort to strive for it. Certainly there are many competencies that people can bring to bear when dealing with life's challenges and problems—but no other capacity will be as integrative as wisdom is. Because of its integrative nature spanning cognitive, motivational, and emotional elements, wisdom can be seen as the most general framework that directs and optimizes human development.

- Proceeding from the definition of wisdom as knowledge, we have begun to explore the emotional and motivational characteristics of individuals with high wisdom-related knowledge. This endeavor can be seen as a first step in testing the idea that wisdom-related knowledge is a resource with emotional and motivational benefits. Proceeding from the general theoretical idea that wisdom involves balance, moderation, and reflectivity, we consider it likely that high wisdom-related knowledge is related to moderate affective experiences and to a balancing of opposing interests and concerns. Confirming this idea, empirical evidence suggests that individuals with higher wisdom-related knowledge report (a) higher affective involvement combined with lower negative and pleasant affect; (b) a value orientation that focuses conjointly on other-enhancing values and personal growth combined with a lesser tendency toward values revolving around a pleasurable life; (c) a preference for cooperative conflict-management strategies combined with a lower tendency to adopt submissive, avoidant, or dominant strategies; and (d) moderate emotional reactions to difficult and uncertain problems (i.e., emotional reactions that are neither extremely high nor extremely low).

References

- Ardelt, M. (2003). Empirical assessment of a three-dimensional wisdom scale. Research on Aging, 25, 275–324.

- Ardelt, M. (2004). Wisdom as expert knowledge system: A critical review of a contemporary operationalization of an ancient concept. Human Development, 47, 257–285.

- Assmann, A. (1994). Wholesome knowledge: Concepts of wisdom in a historical and cross-cultural perspective. In D. L. Featherman, R. M. Lerner, & M. Perlmutter (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol. 12, pp. 187–224). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23, 611–626.

- Baltes, P. B. (1997a). On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. American Psychologist, 52, 366–380.

- Baltes, P. B. (1997b). Wolfgang Edelstein: Über ein Wissenschaftsleben in konstruktivistischer [Wolfgang Edelstein: A scientific life in constructivist melancholy]. Reden zur Emeritierung von Wolfgang Edelstein. Berlin, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Human Devleopment.

- Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In P. B. Baltes & M. M. Baltes (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 27–34). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Baltes, P. B., & Kunzmann, U. (2003). Wisdom: The peak of human excellence in the orchestration of mind and virtue. The Psychologist, 16, 131–133.

- Baltes, P. B., & Kunzmann, U. (2004). The two faces of wisdom: Wisdom as a general theory of knowledge and judgment about excellence in mind and virtue vs. wisdom as everyday realization in people and products. Human Development, 47, 290–299.

- Baltes, P. B., & Smith, J. (1990). Toward a psychology of wisdom and its ontogenesis. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 87–120). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Baltes, P. B., Smith, J., & Staudinger, U. M. (1992). Wisdom and successful aging. In T. B. Sonderegger (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 39, pp. 123–167). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Baltes, P. B., & Staudinger, U. M. (2000). Wisdom: A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. American Psychologist, 55, 122–136.

- Birditt, K. S., Fingerman, K. L., & Almeida, D. M. (2005). Age differences in exposure and reactions to interpersonal tensions: A daily diary study. Psychology and Aging, 20, 330–340.

- Clayton, V., & Birren, J. E. (1980). The development of wisdom across the lifespan: A reexamination of an ancient topic. In P. B. Baltes & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 103–135). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: International University Press.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York, NY: Norton.

- Freund, A. M., & Baltes, P. B. (2002). Life-management strategies of selection, optimization, and compensation: Measurement by self-report and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 642–662.

- Förster, J., Liberman, N., & Higgins, E. T. (2005). Accessibility from active and fulfilled goals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 220–239.

- Glück, J., & Bluck, S. (2013). The MORE life experience model: A theory of the development of personal wisdom. In M. Ferrari & N. M. Weststrate (Eds.), The scientific study of personal wisdom: From contemplative traditions to neuroscience (pp. 75–98). New York, NY: Springer.

- Glück, J., Bluck, S., Baron, J., & McAdams, D. P. (2005). The wisdom of experience: Autobiographical narratives across adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 197–208.

- Heckhausen, J., Dixon, R. A., & Baltes, P. B. (1989). Gains and losses in development throughout adulthood as perceived by different adult age groups. Developmental Psychology, 25, 109–121.

- Helson, R., & Srivastava, S. (2002). Creative and wise people: Similarities, differences, and how they develop. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1430–1440.

- Helson, R., & Wink, P. (1987). Two conceptions of maturity examined in the findings of a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 531–541.

- Holliday, S. G., & Chandler, M. J. (1986). Wisdom: Explorations in adult competence. In J. A. Meacham (Ed.), Contributions to human development (Vol. 17, pp. 1–96). Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

- Jarvis, P. (1987). Meaningful and meaningless experience: Towards an analysis of learning from life. Adult Education Quarterly, 37, 164–172.

- Kekes, J. (1983). Wisdom. American Philosophical Quarterly, 20, 277–286.

- Kekes, J. (1995). Moral wisdom and good lives. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Keltner, D., & Gross, J. J. (1999). Functional accounts of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 467–480.

- König, S., & Glück, J. (2012). Situations in which I was wise: Autobiographical wisdom memories of children and adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22, 512–525.

- Kramer, D. A. (1990). Conceptualizing wisdom: The primacy of affect–cognition relations. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 279–313). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Kramer, D. A. (2000). Wisdom as a classical source of human strength: Conceptualization and empirical inquiry. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 83–101.

- Kross, E., & Grossmann, I. (2012). Boosting wisdom: Distance from the self enhances wise reasoning, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 43–48.

- Kunzmann, U., & Baltes, P. B. (2003a). Beyond the traditional scope of intelligence: Wisdom in action. In R. J. Sternberg, J. Lautry, & T. I. Lubart (Eds.), Models of intelligence for the next millennium (pp. 329–343). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Kunzmann, U., & Baltes, P. B. (2003b). Wisdom-related knowledge: Affective, motivational, and interpersonal correlates. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1104–1119.

- Kunzmann, U., & Baltes, P. B. (2005). The psychology of wisdom: Theoretical and empirical challenges. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Jordan (Eds.), A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives (pp. 110–135). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Kunzmann, U., & Stange, A. (2007). Wisdom as a classical human strength: Psychological conceptualizations and empirical inquiry. In A. D. Ong & M. H. M. van Dulmen (Eds.), Oxford handbook of methods in positive psychology (pp. 306–322). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Kunzmann, U., & Thomas, S. (in preparation). Age differences in negative emotional reactions: Wisdom-related knowledge matters.

- Küpers, W., & Pauleen, D. (2013). A handbook of practical wisdom leadership, organization and integral business practice. Farnham, England: Ashgate.

- Labouvie-Vief, G. (1990). Wisdom as integrated thought: Historical and developmental perspectives. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 52–83). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Labouvie-Vief, G. (2003). Dynamic integration: Affect, cognition, and the self in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 201–206.

- Mickler, C., & Staudinger, U. M. (2008). Personal wisdom: Validation and age-related differences of a performance measure. Psychology and Aging, 23, 787–799.

- Redzanowski, U., & Glück, J. (2013). Who knows who is wise? Self and peer ratings of wisdom. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 391–394.

- Ryan, S. (1996). Wisdom. In K. Lehrer, B. J. Lum, B. A. Slichta, & N. D. Smith (Eds.), Knowledge, teaching, and wisdom (pp. 233–242). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer.

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

- Specht, J., Egloff, B., & Schmukle, S. C. (2011). Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 862–882.

- Staudinger U. M. (1999). Older and wiser? Integrating results on the relationship between age and wisdom-related performance. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23, 641–664.

- Staudinger, U. M., & Glück, J. (2011). Psychological wisdom research: Commonalities and differences in a growing field. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 215–241.

- Staudinger, U. M., & Kunzmann, U. (2005). Positive adult personality development: Adjustment and/or growth? European Psychologist, 10, 320–329.

- Staudinger, U. M., Lopez, D. F., & Baltes, P. B. (1997). The psychometric location of wisdom-related performance. Personality and Social Bulletin, 23, 1200–1214.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1998). A balance theory of wisdom. Review of General Psychology, 2, 347–365.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2001). Why schools should teach for wisdom: The balance theory of wisdom in educational settings. Educational Psychologist, 36, 227–245.

- Sternberg, R., & Jordan, J. (2005). A handbook of wisdom: psychological perspectives. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas, S. (2012). Wisdom-related knowledge about social conflict: Age differences and integration of cognition and affect (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Institute of Psychology, University of Leipzig, Germany.

- Thomas, S., & Kunzmann, U. (2013). Age differences in wisdom-related knowledge: Does the age relevance of the task matter? Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. Advanced online publication.

- Wink, P., & Helson, R. (1997). Practical and transcendent wisdom: Their nature and some longitudinal findings. Journal of Adult Development, 4, 1–15.