Chapter 41

Balancing Individuality and Community in Public Policy

DAVID G. MYERS

We humans are social animals. We come with a need to belong, to connect, to bond. When those needs are met, through intimate friendships and equitable marriages, self-reported happiness runs high and children generally thrive. This chapter describes the need to belong, documents the links between close relationships and subjective well-being, identifies some benefits and costs of modern individualism, and suggests how communitarian public policies might respect both essential liberties and communal well-being.

Who Is Happy?

Who lives with the greatest happiness and life satisfaction? The last quarter-century has offered some surprising, and some not-so-surprising, answers. Self-reported well-being is not much predicted from knowing a person's age or gender (Myers, 1993, 2000). Despite a smoothing of the emotional terrain as people age, and contrary to rumors of midlife crises and later-life angst, happiness is about equally available to healthy men and women of all ages. At all of life's ages and stages, there are many happy people and fewer unhappy. Moreover, despite striking gender differences in ailments such as depression (afflicting more women) and alcoholism (afflicting more men), happiness does not have a favorite gender.

So, who are the relatively happy people?

- As Tay and Diener (2011) indicate, some cultures (especially those where people enjoy political freedom with basic needs met) are conducive to increased satisfaction with life.

- Certain traits and temperaments appear to predispose happiness. Some of these traits, such as extraversion, are genetically influenced. That helps explain Lykken and Tellegen's (1996) finding that about 50% of the variation in current happiness is heritable. Like cholesterol levels, happiness is genetically influenced but not genetically fixed.

- National Opinion Research Center surveys of 49,941 Americans over three decades indicate that people active in faith communities more often report being “very happy” (as have 48% of those attending religious services more than weekly and 26% of those never attending).

Money and Happiness

Does money buy happiness? Many people presume there is some connection between wealth and well-being. From 1970 to 2012, the number of entering American collegians who consider it “very important or essential” that they become “very well off financially” rose from 39% to 81% (UCLA Higher Education Research Institute's annual “American Freshman” reports).

Are people in rich nations, indeed, happier? National wealth does predict national well-being up to a certain point, with diminishing returns thereafter (Myers, 2000). But national wealth rides along with confounding factors such as civil rights, literacy, and years of stable democracy.

Within any nation, are rich people happier? Yes, again, especially in poor countries where low income threatens basic human needs (Argyle, 1999; Diener, Tay, & Oishi, 2013). Nevertheless, the human capacity for adaptation has made happiness nearly equally available to the richest Americans, to lottery winners, to middle income people, and to those who have adapted to disabilities (Myers, 2000).

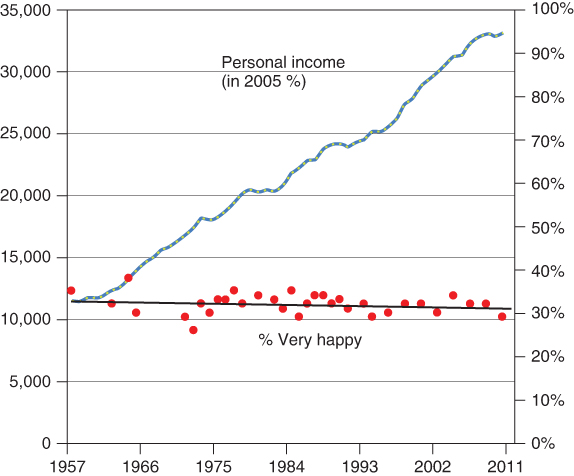

Does economic growth boost happiness? The happiness boost that comes with increased money has a short half-life. Over the past five decades, Americans' per person income, expressed in constant dollars, has more than doubled (thanks to increased real wages into the 1970s, the doubling of women's employment, and increasing nonwage income). Although income inequality has also increased, the rising economic tide has enabled today's Americans to own twice a many cars per person, to eat out more than twice as often, and to mostly enjoy (unlike their 1960 counterparts) dishwashers, clothes dryers, and air conditioning. So, believing that it is very important to be very well off financially and having seen their affluence ratchet upward, are Americans now happier? As Figure 41.1 indicates, their self-reports suggest not.

Figure 41.1 Economic growth and human morale.

Source: Happiness data from General Social Surveys, National Opinion Research Center (2012). Income data from Bureau of the Census (1975) and Economic Indicators.

Economists have recently debated whether economic growth in various countries has produced some increase in personal or social well-being (Easterlin, 1995; Frank, 2012; Stevenson & Wolfers, 2008). It appears that absolute income has some influence on well-being, but that people also adapt to changing income and assess their relative income (which may be steady, even if everyone's income rises).

Not only does wealth but modestly boost well-being, those individuals who strive the hardest for wealth tend to have lower-than-average well-being—a finding that “comes through very strongly in every culture I've looked at,” reported Richard Ryan (quoted in Kohn, 1999; see Kasser & Ryan, 1996). His collaborator, Tim Kasser, concludes from their studies that those who instead strive for “intimacy, personal growth, and contribution to the community” experience a higher quality of life (Kasser, 2000, p. 3; Kasser, Chapter 6, this volume). Ryan and Kasser's research echoes an earlier finding by H. W. Perkins: Among 800 college alumni surveyed, those with “Yuppie values”—who preferred a high income and occupational success and prestige to having very close friends and a close marriage—were twice as likely as their former classmates to describe themselves as “fairly” or “very” unhappy (Perkins, 1991).

We know the perils of materialism, sort of. In a nationally representative survey, Princeton sociologist Robert Wuthnow found that 89% of more than 2,000 participants felt “our society is much too materialistic.” Other people are too materialistic, that is. For 84% also wished they had more money, and 78% said it was “very or fairly important” to have “a beautiful home, a new car and other nice things” (Wuthnow, 1994).

One has to wonder, what's the point? What's the point of accumulating music players full of unplayed music, closets full of seldom worn clothes, garages with luxury cars? What's the point of corporate and government policies that inflate the rich while leaving the working poor to languish? What's the point of leaving huge estates for one's children, as if inherited wealth could buy them happiness, when that wealth could do so much good in a hurting world? (If self-indulgence can't buy us happiness, and cannot buy it for our kids, why not leave any significant wealth we accumulate to bettering the human condition?)

In Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending, Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton (2013) offer practical principles for getting more happiness out of our money. Research has shown that the most expensive forms of leisure (sitting on a yacht) often provide less flow experience than gardening, socializing, or craft work. Money buys more happiness when spent on experiences that you can look forward to, enjoy, and remember than when spent on material stuff. Money spent on a luxury car buys less happiness than money spent on an equally satisfying economy car plus a memorably happy experience. And, surprisingly to many, money given to others often returns more happiness than money spent on self.

Our human capacities for adaptation to changing circumstance and for social comparison give us pause. They imply that the quest for happiness through material achievement requires continually expanding affluence. But the good news is that adaptation to simpler lives can also happen. If we shrink our consumption by choice or by necessity, we will initially feel a pinch, but the pain likely will pass. “Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes with the morning,” reflected the Psalmist. Indeed, thanks to our capacity to adapt and to adjust comparisons, the emotional impact of significant life events—losing a job or even a disabling accident—dissipates sooner than most people suppose.

The Need to Belong1

Aristotle would not be surprised that those who value intimacy and connection are happier than those who lust for money. He called us “the social animal.” Indeed, noted Baumeister and Leary (1995), we humans have a deep need to belong, to feel connected with others in enduring, close, supportive relationships. Soon after birth, we exhibit powerful attachments. We almost immediately prefer familiar faces and voices. By 8 months, we crawl after our caregivers and wail when separated from them. Reunited, we cling.

Adults, too, exhibit the power of attachment. Separated from friends or family—isolated in prison, alone at a new school, living in a foreign land—people feel their lost connections with important others. If, as Barbra Streisand sings, “people who need people are the luckiest people in the world,” then most people are lucky.

Aiding Survival

Social connections serve multiple functions. Social bonds boosted our ancestors' survival rate. By keeping children close to their caregivers, attachments served as a powerful survival impulse. As adults, those who formed attachments were more likely to come together to reproduce and to stay together to nurture their offspring to maturity. To be wretched literally means, in its Middle English origin (wrecche), to be without kin nearby.

Cooperation in groups also enhanced survival. In solo combat, our ancestors were not the toughest predators. But as hunters they learned that six hands were better than two. Those who foraged in groups also gained protection from predators and enemies. If those who felt a need to belong were also those who survived and reproduced most successfully, their genes would in time predominate. The inevitable result: an innately social creature. People in every society on earth belong to groups.

Wanting to Belong

The need to belong colors our thoughts and emotions. We spend a great deal of time thinking about our actual and hoped-for relationships. When relationships form, we often feel joy. Falling in mutual love, people have been known to feel their cheeks ache from their irrepressible grins. Asked, “What is necessary for your happiness?” or “What is it that makes your life meaningful?” most people mention—before anything else—close, satisfying relationships with family, friends, or romantic partners (Berscheid, 1985). Happiness hits close to home.

One study found that very happy university students are not distinguished by their money but by their “rich and satisfying social relationships” (Diener & Seligman, 2002, p. 83).

The need to belong runs deeper, it seems, than any need to be rich. When our need for relatedness is satisfied in balance with two other basic psychological needs—autonomy (a sense of personal control) and competence—the result is a deep sense of well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2002, 2009; Milyavskaya et al., 2009; Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). To feel connected, free, and capable is to enjoy a good life.

Acting to Increase Social Acceptance

When we feel included, accepted, and loved by those important to us, our self-esteem rides high. Indeed, say Leary, Haupt, Strausser, and Chokel (1998), our self-esteem is a gauge of how valued and accepted we feel. Much of our social behavior therefore aims to increase our belonging—our social acceptance and inclusion. To avoid rejection, we generally conform to group standards and seek to make favorable impressions. To win friendship and esteem, we monitor our behavior, hoping to create the right impressions. Seeking love and belonging, we spend billions on clothes, cosmetic products and surgeries, and diet and fitness aids—all motivated by our quest for acceptance.

Maintaining Relationships

For most of us, familiarity breeds liking, not contempt. We resist breaking social bonds. Thrown together at school, at summer camp, on a vacation cruise, people resist the group's dissolution. Hoping to maintain our relationships, we promise to call, to write, to come back for reunions. Parting, we feel distress.

When something threatens or dissolves our social ties, negative emotions overwhelm us. The first weeks living on a college campus away from home distress many students. But if feelings of acceptance and connection build, so do self-esteem, positive feelings, and desires to help rather than hurt others (Buckley & Leary, 2001). When immigrants and refugees move, alone, to new places, the stress and loneliness can be depressing. After years of placing such families individually in isolated communities, today's policies encourage “chain migration” (Pipher, 2002). The second refugee Sudanese family that settles in a town generally has an easier time adjusting than the first.

For children, even a brief time-out in isolation can be an effective punishment. For adults as well as children, social ostracism can be even more painful. To be shunned—given the cold shoulder or the silent treatment, with others' eyes avoiding yours—is to have one's need to belong threatened, observes Williams (2007, 2009; Williams & Zadro, 2001). People often respond to social ostracism with depressed moods, initial efforts to restore their acceptance, and then withdrawal. “It's the meanest thing you can do to someone, especially if you know they can't fight back. I never should have been born,” said Lea, a lifelong victim of the silent treatment by her mother and grandmother. “I came home every night and cried. I lost 25 pounds, had no self-esteem and felt that I wasn't worthy,” reported Richard, after 2 years of silent treatment by his employer.

If rejected and unable to remedy the situation, people sometimes turn nasty. In a series of studies, Twenge and her collaborators (Baumeister, Twenge, & Nuss, 2002; Twenge, Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Bartels, 2007; Twenge, Baumeister, Tice, & Stucke, 2001; Twenge, Catanese, & Baumeister, 2002) either told people (based on a personality test) that they would have “rewarding relationships throughout life” or that “everyone chose you as someone they'd like to work with.” They told other participants that they were “the type likely to end up alone later in life” or that others whom they had met didn't want them in a group that was forming. Those excluded became much more likely to engage in self-defeating behaviors and underperform on aptitude tests. They also exhibited more antisocial behavior, such as by disparaging someone who had insulted them or aggressing (with a blast of noise) against them. “If intelligent, well-adjusted, successful university students can turn aggressive in response to a small laboratory experience of social exclusion,” noted the research team, “it is disturbing to imagine the aggressive tendencies that might arise from a series of important rejections or chronic exclusion from desired groups in actual social life.”

Most socially excluded teens do not commit violence, but some do. Charles “Andy” Williams, described by a classmate as someone his peers derided as “freak, dork, nerd, stuff like that,” went on a shooting spree at his suburban California high school, killing two and wounding 13 (Bowles & Kasindorf, 2001).

Exile, imprisonment, and solitary confinement are progressively more severe forms of punishment. The bereaved often feel life is empty, pointless. Children reared in institutions without a sense of belonging to anyone, or locked away at home under extreme neglect, become pathetic creatures—withdrawn, frightened, speechless. Adults denied acceptance and inclusion may feel depressed. Anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, and guilt all involve threatened disruptions of our need to belong. Even when bad relationships break, people suffer. In one 16-nation survey, separated and divorced people were only half as likely as married people to say they were “very happy” (Inglehart, 1990). After such separations, feelings of loneliness and anger—and sometimes even a strange desire to be near the former partner—are commonplace.

Close Relationships and Happiness

So far we have seen that age, gender, and a rising economic tide are but modest predictors of happiness. Valuing intimacy and connection more than increasing material possessions does predict well-being. It's no wonder, given our human need to belong. So, if that need is met, are people happier? Healthier?

Friendships and Well-Being

Attachments with intimate friends have two effects, believed Francis Bacon (1625): “It redoubleth joys, and cutteth griefs in half.” “I get by with a little help from my friends,” sang John Lennon and Paul McCartney (1967). Indeed, people report happier feelings when with others (Pavot, Diener, & Fujita, 1990).

Asked by National Opinion Research Center interviewers, “How many close friends would you say you have?” (excluding family members), 26% of those reporting fewer than five friends and 38% of those reporting five or more said they were “very happy.”

Marriage and Well-Being

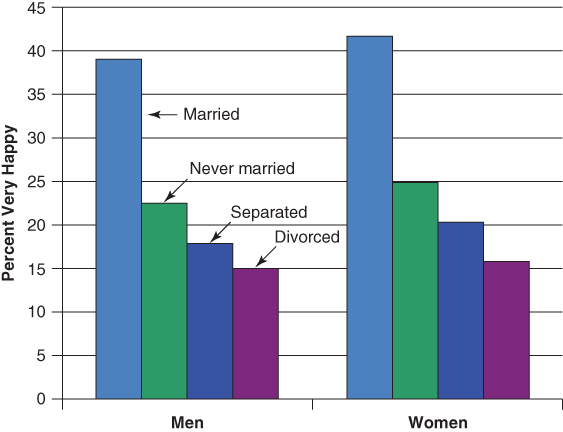

Mountains of data reveal that most people are happier attached. Compared with those who never marry, and especially compared with those who have separated or divorced, married people report greater happiness and life satisfaction. This marriage–happiness correlation extends across countries and (contrary to some pop psychology) both genders (see Figure 41.2).

Figure 41.2 National Opinion Research Center surveys of 35,535 ever-married Americans, 1972 to 2010.

Why are married people happier? Does marriage breed happiness? Or are happy people more likely to marry and stay married? The marriage–happiness traffic appears to run both ways. First, happy people, being more good-natured, outgoing, and sensitive to others, may be more appealing as marital partners. Unhappy people experience more rejection. Misery may love company, but company does not love misery. An unhappy (and therefore self-focused, irritable, and withdrawn) spouse or roommate is generally not fun to be around (Gotlib, 1992; Segrin & Dillard, 1992). For such reasons, positive, happy people more readily form happy relationships.

Yet “the prevailing opinion of researchers,” noted Mastekaasa (1995), is that the marriage–happiness correlation is “mainly due” to the beneficial effects of marriage. Consider: If the happiest people marry sooner and more often, then as people age (and progressively less happy people move into marriage), the average happiness of both married and never-married people should decline. (The older, less happy newlyweds would pull down the average happiness of married people, leaving the unhappiest people in the unmarried group.) However, the data refute this prediction, which suggests that marital intimacy, commitment, and support do, for most people, pay emotional dividends. Marriage offers people new roles that produce new stresses, but it also offers new rewards and sources of identity and self-esteem. When marked by intimacy, marriage (friendship sealed by commitment) reduces loneliness and offers a dependable lover and companion (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1997).

Close Relationships and Health

Linda and Emily had much in common. When interviewed for a study conducted by UCLA psychologist Shelley Taylor (1989), both Los Angeles women had married, raised three children, suffered comparable breast tumors, and recovered from surgery and 6 months of chemotherapy. But there was a difference. Linda, a widow in her early 50s, was living alone, her children scattered in Atlanta, Boston, and Europe. “She had become odd in ways that people sometimes do when they are isolated,” reported Taylor. “Having no one with whom to share her thoughts on a daily basis, she unloaded them somewhat inappropriately with strangers, including our interviewer” (Taylor, 1989, pp. 139–142).

Interviewing Emily was difficult in a different way. Phone calls interrupted. Her children, all living nearby, were in and out of the house, dropping things off with a quick kiss. Her husband called from his office for a brief chat. Two dogs roamed the house, greeting visitors enthusiastically. All in all, Emily “seemed a serene and contented person, basking in the warmth of her family” (Taylor, 1989, pp. 139–142).

Three years later, the researchers tried to reinterview the women. Linda, they learned, had died 2 years before. Emily was still lovingly supported by her family and friends and was as happy and healthy as ever. Because no two cancers are identical, we can't be certain that different social situations led to Linda's and Emily's fates. But they do illustrate a conclusion drawn from several large studies: Social support—feeling liked, affirmed, and encouraged by intimate friends and family—promotes not only happiness, but also health.

Relationships can sometimes be stressful, especially in living conditions that are crowded and lack privacy (Evans, Palsane, Lepore, & Martin, 1989). “Hell is others,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre. Warr and Payne (1982) asked a representative sample of British adults what, if anything, had emotionally strained them the day before. Their most frequent answer? Family. Even when well-meaning, family intrusions can be stressful. And stress contributes to heart disease, hypertension, and a suppressed immune system.

On balance, however, close relationships more often contribute to health and happiness (Tay, Tan, Diener, & Gonzalez, 2012). Asked what prompted yesterday's times of pleasure, the same British sample, by an even larger margin, again answered, “Family.” For most of us, family relationships provide not only our greatest heartaches but also our greatest comfort and joy.

When Brigham Young University researchers combined data from 148 studies totaling more than 300,000 people worldwide, they confirmed a striking effect of social support (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). During the studies, those with ample social connections had survival rates about 50% greater than those with meager connections. The impact of meager connections appeared roughly equal to the effect of smoking 15 cigarettes a day or being alcohol dependent, and double the effect of not exercising or being obese.

Moreover, seven massive investigations, each following thousands of people for several years, revealed that close relationships affect health. Compared with those having few social ties, people are less likely to die prematurely if supported by close relationships with friends, family, fellow workers, members of a church, or other support groups (Cohen, 1988; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Nelson, 1988).

It has long been known that married people live longer, healthier lives than the unmarried. A seven-decade-long Harvard study found that a good marriage at age 50 predicts healthy aging better than does a low cholesterol level at 50 (Vaillant, 2002; see also Vaillant, Chapter 35, this volume). But why? Is it just that healthy people are more likely to marry and stay married? Two recent analyses conclude, after controlling for various possible explanations, that marriage does get under the skin. Marriage “improves survival prospects” (Murray, 2000) and “makes people” healthier and longer-lived (Wilson & Oswald, 2002). What also matters is marital functioning. Positive, happy, supportive marriages are conducive to health; conflict-laden ones are not (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001).

There are several possible reasons for the link between social support and health (Helgeson, Cohen, & Fritz, 1998). Perhaps after symptoms appear family members who offer social support also help patients to receive medical treatment more quickly. Perhaps people eat better and exercise more because their partners guide and goad them into adhering to treatment regimens. Perhaps they smoke and drink less. One study following 50,000 young adults through time found that such unhealthy behaviors drop precipitously after marriage (Marano, 1998). Perhaps supportive relationships also help us evaluate and overcome stressful events, such as social rejection. Perhaps they help bolster our self-esteem. When we are wounded by someone's dislike or by the loss of a job, a friend's advice, assistance, and reassurance may be good medicine (Cutrona, 1986; Rook, 1987).

Environments that support our need to belong also foster stronger immune functioning. Social ties even confer resistance to cold viruses. Cohen, Doyle, Skoner, Rabin, and Gwaltney (1997) demonstrated this after putting 276 healthy volunteers in quarantine for 5 days after administering nasal drops laden with a cold virus. (The volunteers were paid $800 each to endure this experience.) The cold fact is that the effect of social ties is nothing to sneeze at. Age, race, sex, smoking, and other health habits being equal, those with the most social ties were least likely to catch a cold and they produced less mucus. More than 50 studies further reveal that social support calms the cardiovascular system, lowering blood pressure and stress hormones (Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996; Uchino, Uno, & Holt-Lunstad, 1999).

Close relationships also provide the opportunity to confide painful feelings, a social support component that has now been extensively studied (Frattaroli, 2006). In one study, Pennebaker and O'Heeron (1984) contacted the surviving spouses of people who had committed suicide or died in car accidents. Those who bore their grief alone had more health problems than those who could express it openly. Talking about our troubles can be open-heart therapy. Older people, many of whom have lost a spouse and close friends, are somewhat less likely to enjoy such confiding. So, sustained emotional reactions to stressful events can be debilitating. However, the toxic impact of stressful events can be buffered by a relaxed, healthy lifestyle and by the comfort and aid provided by supportive friends and family.

Does Radical Individualism Subvert Our Need to Belong?

We humans have a deep need to belong that, if met, helps sustain our happiness and health. Yet consider some contemporary mantras of Western pop psychology:

Do your own thing. If it feels good, do it. Shun conformity. Don't force your values on others. Assert your personal rights (to sell and buy guns, to sell and buy pornography). To love others, first love yourself. Listen to your own heart. Prefer solo spirituality to communal religion. Be self-sufficient. Expect others likewise to believe in themselves and to make it on their own.

Such sentiments define the heart of economic and social individualism, which finds its peak expression in modern America.

All post-Renaissance Western cultures to some extent express the triumph of individualism as what Fox-Genovese (1991, p. 7) calls “the theory of human nature and rights” (italics in original). But contemporary America is the most individualistic of cultures. One famous comparison of 116,000 IBM employees worldwide found that Americans, followed by Australians, were the most individualistic (Hofstede, 1980). We can glimpse America's individualism in its comparatively low tax rates. Taxes advance the common good through schools, roads, parks, and health, welfare, and defense programs that serve and protect all—but at a price to individuals. And in the contest among American values, individual rights trump social responsibilities.

Individualism is a two-sided coin. It supports democracy by fostering initiative, creativity, and equal rights for all individuals. But taken to an extreme it becomes egoism and narcissism—the self above others, one's own present above posterity's future. Shunning conformity, commitment, and obligation, modern individualists prefer to define their own standards and do as they please, noted Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, and Tipton (1985) in their discernment of American Habits of the Heart. And as Robert Putnam (2000) massively documented, we have become more, not less individualistic. Compared to a half century ago, we are more often “bowling alone,” and also voting, visiting, entertaining, car-pooling, trusting, joining, meeting, neighboring, and giving proportionately less. Social capital—the family and community networks that nurture civility and mutual trust—has waned.

The celebration and defense of personal liberty lies at the heart of the American dream. It drives our free market economy and underlies our respect for the rights of all. In democratic countries that guarantee basic freedoms, people live more happily than in those that don't. Migration patterns testify to this reality. Yet for today's radical individualism, we pay a price: a social recession that has imperiled children, corroded civility, and slightly diminished happiness. When individualism is taken to an extreme, individual well-being can become its ironic casualty.

Is Inequality Socially Toxic?

Individualism also supports inequality, and in both developed and emerging economies inequality has grown. In the 34 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2011) countries, the richest 10% now average 9 times the income of the poorest 10%. (The gap is less in the Scandinavian countries, and substantially greater in Israel, Turkey, the United States, Mexico, and Chile.) Countries with greater inequality not only have greater health and social problems, but also higher rates of mental illness (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2011). Likewise, American states with greater inequality have higher rates of depression (Messias, Eaton, & Grooms, 2011). And over time, years with more income inequality—and associated increases in perceived unfairness and lack of trust—correlate with less happiness among those with lower incomes (Oishi, Kesebir, & Diener, 2011).

Although people often prefer the economic policies in place, a national survey found that Americans overwhelmingly preferred an income distribution that just happened to be Sweden's. Moreover, people preferred (in an ideal world) the top 20% income share ranging between 30% and 40% (rather than the actual 84%), with modest differences between Republicans and Democrats and between those making less than $50,000 and more than $100,000 (Norton & Ariely, 2011).

Even in China, income inequality has grown. This helps explain why rising affluence has not produced increased happiness—there or elsewhere. Rising income inequality, notes Michael Hagerty (2000), makes for more people who have rich neighbors. Television's modeling of the lifestyles of the wealthy also serves to accentuate feelings of “relative deprivation” and desires for more (Schor, 1998).

A Vision of a More Connected Future

To counter radical individualism and the other forces of cultural corrosion, one can affirm the following:

- Liberals' indictment of the demoralizing effects of poverty and conservatives' indictment of toxic media models.

- Liberals' support for family-friendly workplaces and conservatives' support for committed relationships.

- Liberals' advocacy for children in all sorts of families and conservatives' support for marriage and coparenting.

Without suppressing our differences do most people not share a vision of a better world? Is it not one that rewards initiative but restrains exploitative greed? That balances individual rights with communal well-being? That respects diversity while embracing unifying ideals? That is accepting of other cultures without being indifferent to moral issues? That protects and heals our degrading physical and social environments? In our utopian social world, adults and children will together enjoy their routines and traditions. They will have close relationships with extended family and with supportive neighbors. Children will live without fear for their safety or the breakup of their families. Fathers and mothers will jointly nurture their children; to say “He fathered the child” will parallel the meaning of “She mothered the child.” Free yet responsible media will entertain us with stories and images that exemplify heroism, compassion, and committed love. Reasonable and rooted moral judgments will motivate compassionate acts and enable noble and satisfying lives.

The Communitarian Movement

Supported by research on the need to belong, on the psychology of women, and on communal values in Asian and Third World cultures, many social scientists are expressing renewed appreciation for human connections. A late-20th-century communitarian movement offered a third way—an alternative to the individualistic civil libertarianism of the left and the economic libertarianism of the right. It implored us, in the words of Martin Luther King Jr., “to choose between chaos and community,” to balance our needs for independence and attachment, liberty and civility, me thinking and we thinking. The communitarian platform “recognizes that the preservation of individual liberty depends on the active maintenance of the institutions of civil society.”

Typically, conservatives are economic individualists and moral collectivists. Liberals are moral individualists and economic collectivists. Third-way communitarians have advocated moral and economic policies that balance rights with communal responsibility. “Democratic communitarianism is based on the value of the sacredness of the individual, which is common to most of the great religions and philosophies of the world,” explained Bellah (1995/1996, pp. 4–5). But it also “affirms the central value of solidarity…that we become who we are through our relationships.” Agreeing that “it takes a village to raise a child,” communitarians remind us of what it takes to raise a village.

Listen to communitarians talk about European-style child benefits, extended parental leaves, flexible working hours, campaign finance reform, and ideas for “fostering the commons,” and you'd swear they are liberals. Listen to them talk about covenant marriages, divorce reform, father care, and character education, and you'd swear they are conservatives.

Communitarians have welcomed incentives for individual initiative and appreciate why Marxist economies have crumbled. “If I were, let's say, in Albania at this moment,” said Communitarian Network cofounder Etzioni (1991, p. 35), “I probably would argue that there's too much community and not enough individual rights.” In communal Japan (where “the nail that sticks out gets pounded down”), Etzioni said he would sing a song of individuality. In the individualistic Western context, he has sung a song of social order, which in times of chaos (as in crime-plagued or corrupt countries) is necessary for liberty (Etzioni, 1994). Where there is chaos in a neighborhood, people may feel like prisoners in their homes.

Opposition to communitarians has come from civil libertarians of the left, economic libertarians of the right, and special interest libertarians (such as the American National Rifle Association in the 2013 debate over gun control). Much as these organizations differ, they are branches of the same tree—all valuing individual rights in the contest with the common good. Communitarians take on all such varieties of libertarians. Unrestrained personal freedom, they say, destroys a culture's social fabric; unrestrained commercial freedom exploits workers and plunders the commons. Etzioni (1998) sums up the communitarian ideal in his New Golden Rule: “Respect and uphold society's moral order as you would have society respect and uphold your autonomy” (p. xviii).

To reflect on your own libertarian versus communitarian leanings, consider what restraints on liberty you support: luggage scanning at airports? Smoking bans in public places? Speed limits on highways? Sobriety checkpoints? Drug testing of pilots and rail engineers? Prohibitions on leaf burning? Restrictions on TV cigarette ads? Regulations on stereo or muffler noise? Pollution controls? Requiring seat belts and motorcycle helmets? Disclosure of sexual contacts for HIV carriers? Outlawing child pornography? Background checks before gun purchases? Banning AK-47s and other nonhunting weapons of destruction? Required school uniforms? Wire taps on suspected terrorists? Fingerprinting checks to protect welfare, unemployment, and Social Security funds from fraud?

All such restraints on individual rights, most opposed by libertarians of one sort or another, aim to enhance the public good. When New York City during the 1990s took steps to control petty deviances—the panhandlers, prostitutes, and sex shops—it made the city into a more civil place, with lessened crime and fear. “It is better to live in an orderly society than to allow people so much freedom they can become disruptive,” two thirds of Canadians but only one half of Americans have agreed (Lipset & Pool, 1996, p. 42).

Libertarians often object to restraints on guns, panhandlers, pornography, drugs, or business by warning that such may plunge us down a slippery slope leading to the loss of more important liberties. If today we let them search our luggage, tomorrow they'll be invading our houses. If today we censor cigarette ads on television, tomorrow the thought police will be removing books from our libraries. If today we ban assault weapons, tomorrow's Big Brother government will take our hunting rifles. Communitarians reply that if we don't balance concern for individual rights with concern for the commons, we risk chaos and a new fascism. The true defenders of freedom, contends Etzioni, are those who seek to balance rights with responsibilities, individualism with community, and liberty with fraternity.

This broadly based social ecology movement affirms liberals' concerns about income inequality and their support for family-friendly workplaces and children in all family forms. It affirms conservatives' indictments of toxic media models and their support for marriage and coparenting. And it found encouragement in the recent subsiding of teen violence, suicide, and pregnancy.

Conclusion

To sum up, humans are social animals. We flourish when connected in close, supportive relationships.

Summary Points

- Human happiness is not much predicted by age or gender, but it does tend to be greater among those with certain traits, those in countries where basic needs are met and people experience freedom, and those active in supportive faith communities.

- People in rich (rather than poor) countries and rich (compared to poor) individuals do report greater happiness. Yet, unlike a rising tide, economic growth over time has not substantially lifted our emotions.

- People who prioritize intimacy and connection report greater quality of life than those who prioritize wealth and material possessions.

- The human need to belong is apparent from

- – The survival value of attachments and cooperative action.

- – Our desire for close, satisfying relationships with family, friends, and romantic partners.

- – Our efforts to gain acceptance, through tactics that range from conformity to cosmetic surgery.

- – Our distress over lost relationships, ostracism, or exile.

- Close relationships, such as intimate friendship and marriage, predict health as well as happiness.

- Western individualism fosters initiative, creativity, and human rights. But taken to an extreme it can also foster egoism, erode the communal social fabric, and increase inequality.

- Economic inequality is a predictor of increased social, emotional, and health problems.

- Communitarians seek to advance human flourishing with public policies that balance individual incentives and rights with communal solidarity and well-being.

For public policy makers these are important points to ponder—perhaps especially in my country, where

- The child poverty rate has increased (from 16% to 22% between 1999 and 2011, reports Child Trends, 2012).

- The gap between rich and poor also continues to increase. Between 1970 and 2011, the richest 1% of Americans' share of the national income pie more than doubled—from 9% to 20% (Kuziemko & Stantcheva, 2013).

Bipartisan voices recognize that liberals' social risk factors (poverty, inequality, hopelessness) and conservatives' social risk factors (early sexualization, unwed parenthood, family fragmentation) all come in the same package. For example, a 2013 “Call for a New Conversation on Marriage,” signed by 75 American leaders from across the political spectrum, “brings together gays and lesbians who want to strengthen marriage with straight people who want to do the same.” It asks, for example, “What economic policies strengthen marriage?” and “What marriage policies create wealth?” (Institute for American Values, 2013). Recognizing our need to belong and having a vision for positive communal life, practitioners of positive psychology may wish to ponder and explore such questions, and to join the effort to promote a social ecology that nurtures happiness, health, and civility.

References

- Argyle, M. (1999). Causes and correlates of happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwartz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 353–373). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Bacon, F. (1625). Of friendship. The essays or counsels, civil and moral. London, England: Iohn Haviland for Hanna Barret.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachment as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

- Baumeister, R. F., Twenge, J. M., & Nuss, C. K. (2002). Effects of social exclusion on cognitive processes: Anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent thought. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 817–827.

- Bellah, R. N. (1995/1996, Winter). Community properly understood: A defense of “democratic communitarianism.” The Responsive Community, 49–54.

- Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Berscheid, E. (1985). Interpersonal attraction. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 413–484). New York, NY: Random House.

- Bowles, S., & Kasindorf, M. (2001, March 6). Friends tell of picked-on but “normal” kid. USA Today, p. 4A.

- Buckley, K. E., & Leary, M. R. (2001, February). Perceived acceptance as a predictor of social, emotional, and academic outcomes. Paper presented at the Society of Personality and Social Psychology annual convention, San Antonio, TX.

- Bureau of the Census. (1975). Historical abstract of the United States: Colonial times to 1970. Washington, DC: Superintendent of Documents.

- Child Trends (2012, October). Children in poverty: Indicators on children and youth. Retrieved from www.ChildTrendsDataBank.org

- Cohen, S. (1988). Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology, 7, 269–297.

- Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Skoner, D. P., Rabin, B. S., & Gwaltney, J. M., Jr. (1997). Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. Journal of the American Medical Association, 277, 1940–1944.

- Cutrona, C. E. (1986). Behavioral manifestations of social support: A microanalytic investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 201–208.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Self-determination theory: A consideration of human motivational universals. In P. J. Corr & G. Matthews (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personality psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13, 81–84.

- Diener, E., Tay, L., & Oishi, S. (2013). Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 104(2), 267–276.

- Dunn, E., & Norton, M. (2013). Happy money: The science of smarter spending. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Easterlin, R. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 27, 35–47.

- Etzioni, A. (1991, May–June). The community in an age of individualism. Interview in The Futurist, 35–39.

- Etzioni, A. (1994). The spirit of community: The reinvention of American society. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Etzioni, A. (1998). The new golden rule. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Evans, G. W., Palsane, M. N., Lepore, S. J., & Martin, J. (1989). Residential density and psychological health: The mediating effects of social support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 994–999.

- Fox-Genovese, E. (1991). Feminism without illusions: A critique of individualism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Frank, R. H. (2012). The Easterlin paradox revisited. Emotion, 12, 1188–1191.

- Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 823–865.

- Gotlib, I. H. (1992). Interpersonal and cognitive aspects of depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1, 149–154.

- Hagerty, M. R. (2000). Social comparisons of income in one's community: Evidence from national surveys of income and happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 764–771.

- Helgeson, V. S., Cohen, S., & Fritz, H. L. (1998). Social ties and cancer. In J. C. Holland (Ed.), Psycho-oncology (pp. 730–742). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (1997). Love and satisfaction. In R. J. Sternberg & M. Hojjat (Eds.), Satisfaction in close relationships (pp. 56–78). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7, e1000316.

- House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545.

- Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Institute for American Values. (2013). A call for a new conversation about marriage. Retrieved from www.americanvalues.org

- Kasser, T. (2000). Two versions of the American dream: Which goals and values make for a high quality of life? In E. Diener & D. R. Rahtz (Eds.), Advances in quality of life: Theory and research (Vol. 1, pp. 3–12). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280–287.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Newton, T. L. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503.

- Kohn, A. (1999, February 2). In pursuit of affluence, at a high price. New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com

- Kuziemko, I., & Stantcheva, S. (2013, April 21). Our feelings about inequality: It's complicated. New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com

- Leary, M. R., Haupt, A. L., Strausser, K. S., & Chokel, J. T. (1998). Calibrating the sociometer: The relationship between interpersonal appraisals and state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1290–1299.

- Lennon, J., & McCartney, P. (1967). Sgt. Pepper's lonely hearts club band [Album].

- Lipset, S. M., & Pool, A. B. (1996, Summer). Balancing the individual and the community: Canada versus the United States. The Responsive Community, 37–46.

- Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7, 186–189.

- Marano, H. E. (1998, August 4). Debunking the marriage myth: It works for women, too. New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com

- Mastekaasa, A. (1995). Age variations in the suicide rates and self-reported subjective well-being of married and never married persons. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 5, 21–39.

- Messias, E., Eaton, W. W., & Grooms, A. N. (2011). Income inequality and depression prevalence across the United States: An ecological study. Psychiatric Services, 62, 710–712.

- Milyavskaya, M., Gingras, I., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Gagnon, H., Fang, J., & Bolché, J. (2009). Balance across contexts: Importance of balanced need satisfaction across various life domains. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1031–1045.

- Murray, J. E. (2000). Marital protection and marital selection: Evidence from a historical-prospective sample of American men. Demography, 37, 511–521.

- Myers, D. G. (1993). The pursuit of happiness. New York, NY: Avon.

- Myers, D. G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55, 56–67.

- National Opinion Research Center. (2012). General social survey data for 1972 to 2010. Retrieved from http://sda.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/hsda?harcsda+gss12

- Nelson, N. (1988). A meta-analysis of the life-event/health paradigm: The influence of social support (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Temple University, Philadelphia, PA.

- Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. (2011). Building a better America—one wealth quintile at a time. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 9–12.

- Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22, 1095–1100.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2011). An overview of growing income inequalities in OECD countries: Main findings. Paris: Author. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/49499779.pdf

- Pavot, W., Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1990). Extraversion and happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 1299–1306.

- Pennebaker, J. W., & O'Heeron, R. C. (1984). Confiding in others and illness rate among spouses of suicide and accidental death victims. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 473–476.

- Perkins, H. W. (1991). Religious commitment, Yuppie values, and well-being in post-collegiate life. Review of Religious Research, 32, 244–251.

- Pickett, K., & Wilkinson, R. (2011). The spirit level: Why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

- Pipher, M. B. (2002). The middle of everywhere: The world's refugees come to our town. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace.

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Rook, K. S. (1987). Social support versus companionship: Effects on life stress, loneliness, and evaluations by others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1132–1147.

- Schor, J. B. (1998). The overworked American. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Segrin, C., & Dillard, J. P. (1992). The interactional theory of depression: A meta-analysis of the research literature. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 11, 43–70.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Niemiec, C. P. (2006). It's not just the amount that counts: Balanced need satisfaction also affects well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 331–341.

- Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subject well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 39, 1–87.

- Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 354–365.

- Tay, L., Tan, K., Diener, E., & Gonzalez, E. (2012). Social relations, health behaviors, and health outcomes: A survey and synthesis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 5, 28–78.

- Taylor, S. E. (1989). Positive illusions: Creative self-deception and the healthy mind. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. J., & Bartels, J. M. (2007). Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 56–66.

- Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Stucke, T. S. (2001). If you can't join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 1058–1069.

- Twenge, J. M., Catanese, K. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Social exclusion causes self-defeating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 606–615.

- Uchino, B. N., Cacioppo, J. T., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (1996). The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 488–531.

- Uchino, B. N., Uno, D., & Holt-Lunstad, J. (1999). Social support, physiological processes, and health. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 145–148.

- Vaillant, G. E. (2002). Aging well: Surprising guideposts to a happier life from the landmark Harvard study of adult development. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Warr, P., & Payne, R. (1982). Experiences of strain and pleasure among British adults. Social Science and Medicine, 16, 1691–1697.

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 425–452.

- Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 275–313.

- Williams, K. D., & Zadro, L. (2001). Ostracism: On being ignored, excluded and rejected. In M. Leary (Ed.), Rejection (pp. 21–53). New New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, C. M., & Oswald, A. J. (2002). How does marriage affect physical and psychological health? A survey of the longitudinal evidence. Working paper, University of York and Warwick University.

- Wuthnow, R. (1994). God and Mammon in America. New York, NY: Free Press.