Chapter 9

A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Fostering Healthy Self-Regulation From Within and Without

KIRK WARREN BROWN AND RICHARD M. RYAN

Many theories view motivation as a unitary phenomenon that varies only in its strength. Yet a deeper analysis readily shows that individuals vary not only in how much motivation they possess but also in the orientation or type of motivation that energizes their behavior. For example, some people go to work each day because they find their jobs interesting, meaningful, even enjoyable, whereas others may do the same thing only because financial pressures demand it. Similarly, some students study out of a deep curiosity and an inner desire to learn, whereas others study only to obtain good grades or meet requirements. In these examples, both groups may be highly motivated, but the nature and focus of the motivation—that is, the “why” of the person's behavior—clearly varies, as do the consequences. For instance, the curious student may learn more than the required material, process it more deeply, talk more with others about it, and remember it more enduringly. This difference may not show up immediately on a test score, but it may have many ramifications for the student's emotional and intellectual development.

Self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000) argues that motivational orientations that guide behavior have important consequences for healthy behavioral regulation and psychological well-being. Self-determination theory distinguishes between various types of motivation based on the implicit or explicit reasons or goals that give impetus to behavior. Among the ways in which motivation varies, of primary consideration is the relative autonomy of an individual's activity. Autonomously motivated behavior is self-endorsed, volitional, and done willingly; that is, it is self-determined. In contrast, behavior that lacks autonomy is motivated by real or perceived controls, restrictions, and pressures, arising either from social contextual or internal forces.

The importance of the relative autonomy of motivated behavior is borne out by evidence suggesting that autonomy is endorsed as a primary need and source of satisfaction to people across diverse cultures (Sheldon, Elliot, Kim, & Kasser, 2001) and promotes positive outcomes in varied cultural contexts as well (e.g., Chirkov, Ryan, Kim, & Kaplan, 2003; Jang, Reeve, Ryan, & Kim, 2009). The fundamental nature of this motivational dimension is also seen at the level of social groups. Over the course of recorded history, autonomy and self-determination have often been rallying cries among those seeking social change in the midst of oppressive or restrictive political or economic climates. Most importantly for the present discussion, however, the relative autonomy of behavior has important consequences for the quality of experience and performance in every domain of behavior, from health care to religious practice, and from education to work. In this chapter, we discuss the nature of motivation in terms of its relative autonomy and review evidence in support of its role in positive psychological and behavioral outcomes. In accord with the theme of this volume, a central focus of this discussion is the practical implications of this work—specifically, how to foster autonomy. We begin by describing variations in the orientation of motivations as outlined within SDT. We then address factors that impact motivation at two levels:

- How motivators and social contexts can foster or undermine autonomous motivation.

- How individuals can best access and harness self-regulatory powers from within.

The Nature of Autonomous Regulation

For more than three decades, scholarship in motivation has highlighted the primary distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic reasons for behavioral engagement. Intrinsic motivation represents a natural inclination toward assimilation, exploration, interesting activity, and mastery. Activities are intrinsically motivated when they are done for the interest and enjoyment they provide. In contrast, extrinsically motivated activities are those done for instrumental reasons or performed as a means to some separable end. This basic motivational distinction has important functional value, but SDT takes a more nuanced view, postulating a spectrum model of regulation, wherein behavior can be guided by intrinsic motivation and by several forms of extrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). These extrinsic motivations can range from those that entail mere passive compliance or external control to those that are characterized by active personal commitment and meaningfulness. That is, even extrinsic motives vary in the degree to which they are autonomous or self-determined and, therefore, according to SDT, have different consequences for well-being and the quality and persistence of action.

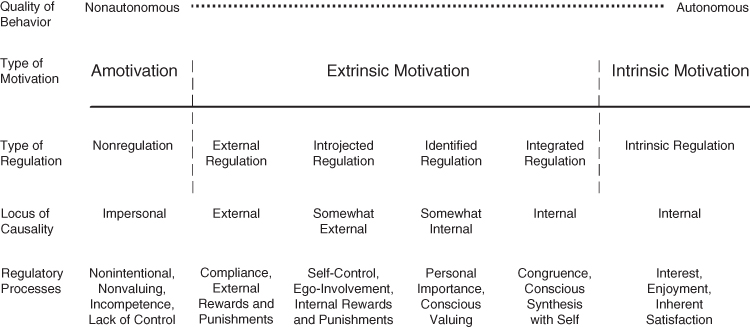

A subtheory within SDT, organismic integration theory (OIT), details this continuum of motivation and the contextual factors that either support or hinder internalization and integration of the regulation of behavior (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Figure 9.1 displays the taxonomy of motivational types described by OIT, arranged from left to right according to the extent to which behavior is externally or internally regulated. At the far left of the continuum is amotivation, representing a non-self-regulated state in which behavior is performed without intent or will or is not engaged in at all. Amotivation occurs when an individual can assign no meaning or value to the behavior, feels incompetent to perform it, or does not expect a desired outcome to result from performing it. The rest of the continuum displayed in Figure 9.1 outlines five conceptually and empirically distinct types of intentional behavioral regulation. At the far right is intrinsic motivation, the doing of an activity for its inherent enjoyment and interest. Such behavior is highly autonomous and represents a gold standard against which the relative autonomy of other forms of regulation are measured. Intrinsic motivation has been associated with a number of positive outcomes, including creativity (e.g., Amabile, 1996), enhanced task performance (Grolnick & Ryan, 1989; Murayama et al., in press), and higher psychological well-being (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

Figure 9.1 The autonomy continuum showing types of motivation and their corresponding regulatory styles, processes, and loci of causality.

On the spectrum between amotivation and intrinsic motivation lie four types of extrinsic motivation that vary in the degree of autonomy that each affords. Least autonomous among these types of extrinsic motivation is external regulation. Externally regulated behaviors are performed in accord with some external contingency—to obtain reward or avoid punishment or to otherwise comply with a salient demand. The phenomenology of external regulation is one of feeling controlled by forces or pressures outside the self, or, in attributional terms, behavior is perceived as having an external locus of causality (DeCharms, 1968; Ryan & Deci, 2004).

Behavior arising from introjected regulation is similar to that which is externally regulated in that it is controlled, but in this second form of extrinsic motivation, behavior is performed to meet self-approval-based contingencies. Thus, when operating from introjection, a person behaves to attain ego rewards such as pride or to avoid guilt, anxiety, or disapproval from self or others. Introjection has also been described as contingent self-esteem (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1995; Ryan & Brown, 2003). A common manifestation of introjection is ego involvement (Ryan, 1982), in which an individual is motivated to demonstrate ability to maintain a sense of self-worth. Although ego involvement can be highly motivating under particular circumstances (e.g., Ryan, Koestner, & Deci, 1991), it is associated with a number of negative consequences, including greater stress, anxiety, self-handicapping, and unstable persistence.

Identified regulation is a more autonomous form of extrinsic motivation, wherein a behavior is consciously valued and embraced as personally important. For example, a person may write daily in a journal because he or she values the self-insight and clarity of mind that come from that activity. Identification represents, in attributional terms, an internal perceived locus of causality—it feels relatively volitional or self-determined. Thus, identified motivation is associated with better persistence and performance compared to behaviors motivated by external or introjected regulations, as well as more positive affect.

Finally, the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation. Behaviors that are integrated are not only valued and meaningful but also consciously assimilated into the self and brought into alignment with other values and goals. Like behaviors that are intrinsically motivated, integrated actions have an internal locus of causality and are self-endorsed, but because they are performed to obtain a separable outcome rather than as an end in themselves, they are still regarded as extrinsic.

Self-determination theory posits that as children grow older, most socialized behavior comes to be regulated in a more autonomous fashion because there is an overarching developmental tendency to seek the integration of behavioral regulation into the self (Chandler & Connell, 1987; Ryan, 1995). But this integrative process is not inevitable, and there are many factors that can disrupt or derail this tendency. Thus, the motivational model outlined in Figure 9.1 does not propose that individuals typically progress through the various forms of extrinsic motivation on their way to integrated or intrinsic regulation. Instead, when new behaviors are undertaken, any one of these motivational starting points may be predominant as a function of the content of the goal and the presence of social and situational supports, pressures, and opportunities.

The greater internalization and integration of regulation into the self, the more self-determined behavior is felt to be. Early empirical support for this claim was obtained by Ryan and Connell (1989) in a study of achievement behaviors among elementary school children. Assessing external, introjected, identified, and intrinsic reasons for engaging in academically related behaviors (e.g., doing homework), they found that the four types of regulation were intercorrelated in a quasi-simplex or ordered pattern that lent empirical support to the theorized continuum of relative autonomy. The children's differing motivational styles for academic work were also related to their achievement-related attitudes and psychological adjustment. Students whose work was done for external reasons showed less interest and weaker effort, and they tended to blame teachers and others for negative academic outcomes. Introjected regulation was related to effort expenditure but also to higher anxiety and maladaptive coping with failure. Identified regulation was associated with more interest and enjoyment of school, greater effort, and a greater tendency to cope adaptively with stressful circumstances.

Recent research has extended these findings on motivational style and outcome, showing, for example, that more autonomous extrinsic motivation is associated with greater academic engagement and performance, lower dropout rates, higher quality learning, and greater psychological well-being across cultures (see Deci & Ryan, 2012, for review). Positive outcomes linked with higher relative autonomy have also been found in the health care and psychotherapy domains, in which greater internalization of treatment protocols has been associated with higher levels of adherence and success. In fact, a number of clinical trials in areas such as obesity, medication adherence, smoking, dental hygiene, and other areas have demonstrated efficacy for SDT techniques in enhancing behavioral and health outcomes (Ryan, Patrick, Deci, &Wiliams, 2008). A number of studies relating autonomy and autonomy support to better outcomes in treatment of psychological issues have also emerged (e.g., Zuroff et al., 2007).

In fact, autonomous regulation of behavior has been associated with positive outcomes in a wide variety of life domains, including relationships (e.g., LaGuardia & Patrick, 2008), work (e.g., Ryan, Bernstein, & Brown, 2010), religion (e.g., Baard & Aridas, 2001), virtual worlds (e.g., Rigby & Ryan, 2011), and environmental practices (Pelletier, 2002), among others. These benefits include greater persistence in, and effectiveness of, behavior and enhanced well-being.

Facilitating Autonomous Functioning Through Social Support

Considerable research has been devoted to examining social conditions that promote autonomous regulation, including both intrinsic motivation and more autonomous forms of extrinsic motivation. Despite the fact that the human organism has evolved capacities and tendencies toward the autonomous regulation of behavior (Deci & Ryan, 2000), biological, social, and other environmental influences can facilitate or undermine those tendencies. An understanding of the nature of these influences is important because, as reviewed previously, autonomous versus heteronomous functioning has manifold personal consequences.

Supporting Intrinsic Motivation

As already noted, intrinsic motivation represents a distinctly autonomous form of functioning, in that behavior is performed for its own sake and is wholly self-endorsed. Cognitive evaluation theory (CET), another subtheory within SDT, was proposed by Deci and Ryan (1980, 1985) to specify the social contextual features that can impact, both positively and negatively, intrinsic motivational processes. Cognitive evaluation theory began with the assumption that although intrinsic motivation is a propensity of the human organism, it will be catalyzed or facilitated in circumstances that support its expression and hindered under social circumstances that undercut it. Among its major tenets, CET specifies that intrinsic motivation depends on conditions that allow (a) an experience of autonomy or an internal perceived locus of causality, and (b) the experience of effectance or competence. Factors that undermine the experiences of either autonomy or competence, therefore, undermine intrinsic motivation.

Among the most controversial implications of CET is the proposition that contexts in which rewards are used to control behavior undermine intrinsic motivation and yield many hidden costs that were unanticipated by reward-based theories of motivation. Although much debated, the most definitive summary of that research has shown that extrinsic rewards made contingent on task performance reliably weaken intrinsic motivation (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). Cognitive evaluation theory specifies that this occurs because contingent rewards, as typically employed, foster the recipient's perception that the cause of their behavior lies in forces external to the self. Individuals come to see themselves as performing the behavior for the reward or the rewarding agent and thus not because of their own interests, values, or motivations. Accordingly, behavior becomes reward dependent, and any intrinsic motivation that might have been manifest is undermined. However, rewards are not the only type of influence that undermines intrinsic motivation. When motivators attempt to move people through the use of threats, deadlines, demands, external evaluations, and imposed goals, intrinsic motivation is diminished (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Evidence also highlights factors that can enhance intrinsic motivation. Laboratory and field research show that the provision of choice and opportunities for self-direction and the acknowledgment of perspectives and feelings serve to enhance intrinsic motivation through a greater felt sense of autonomy. Such factors can yield a variety of salutary consequences. For example, evidence indicates that teachers who support autonomy (see Reeve, Bolt, & Cai, 1999, for specific teacher strategies) spark curiosity, a desire for challenge, and higher levels of intrinsic motivation in their students. In contrast, a predominantly controlling teaching style leads to a loss of initiative and less effective learning, especially when that learning concerns complex material or requires conceptual, creative processing (e.g., Jang et al., 2009). In a similar vein, children of parents who are more autonomy-supportive show a stronger mastery orientation, manifest in greater spontaneous exploration and extension of their capacities, than children of more controlling parents (Grolnick & Apostoleris, 2002).

The support of autonomy in fostering intrinsic motivation is thus very critical. Yet, although autonomy support is a central means by which intrinsic motivation is facilitated, CET specifies that supports for the other basic psychological needs proposed by SDT, namely competence and relatedness, are also important, especially when a sense of autonomy is also present. Deci and Ryan (1985) review evidence showing that providing optimal challenge, positive performance feedback, and freedom from controlling evaluations facilitate intrinsic motivation, whereas negative performance feedback undermines it. Vallerand and Reid (1984) found that these effects are mediated by the individual's own perceived competence.

Intrinsic motivation also appears to more frequently occur in relationally supportive contexts. This is so from the beginning of development. As Bowlby (1979) suggested and research has confirmed (e.g., Frodi, Bridges, & Grolnick, 1985), the intrinsic motivational tendencies evident in infants' exploratory behavior are strongest when a child is securely attached to a caregiver. Self-determination theory further argues that a sense of relatedness can facilitate intrinsic motivation in older children and adults, a claim also supported by research (e.g., Ryan, Stiller, & Lynch, 1994). Practically, when teachers, parents, managers, and other motivators convey caring and acceptance, the motivatee is freed up to invest in interests and challenges that the situation presents.

In sum, research has supported CET by demonstrating how the expression of intrinsic motivation is supported by social conditions that promote a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which together make up the triad of basic psychological needs specified within SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000). However, by definition, intrinsic motivation will be manifest only for activities that potentially offer inherent interest or enjoyment to the individual—for example, those that offer novelty, have aesthetic value, or produce excitement. For activities that do not carry such appeal, the principles of CET do not apply. However, the role of autonomy in positive experience is not limited to intrinsically motivated behavior, and, in fact, intrinsically motivated behavior may be comparatively rare in everyday life (Ryan & Deci, 2000). This brings us to a discussion of the wide range of behaviors that have an extrinsic motivational basis.

Supporting More Autonomous Extrinsic Motivation

Beginning in early childhood, the ratio of intrinsic to extrinsic motivation begins to shift dramatically in the direction of extrinsic activities. Indeed, as we grow older, most of us spend less and less time simply pursuing what interests us and more and more time pursuing goals and responsibilities that the social world obliges us to perform (Ryan, 1995). Given both the prevalence of extrinsic motivation and the positive consequences that accrue from autonomous functioning, an issue of key importance is how the self-regulation of these imposed activities can be facilitated by socializing agents such as parents, teachers, physicians, bosses, coaches, or therapists. Self-determination theory frames this issue in terms of how to foster the internalization and integration of the value and regulation of extrinsically motivated behavior. As noted already, internalization refers to the adoption of a value or regulation, and integration involves the incorporation of that regulation into the sense of self, such that the behavior feels self-endorsed and volitional.

Empirical research indicates that the presence of social supports for the psychological needs of competence, relatedness, and autonomy appears to foster not only the autonomous functioning seen in intrinsically motivated behavior but also the internalization and integration of behaviors focused on extrinsic goals. For example, when individuals do not have intrinsic reasons for engaging in a particular behavior, they do so primarily because the activity is prompted, modeled, or valued by another person or a group to which the individual feels, or wants to feel, in relationship. Organismic integration theory posits that internalization is more likely to occur when supports for feelings of relatedness or connectedness are present. For example, Ryan et al. (1994) found that children who felt securely attached to their parents and teachers showed more complete internalization of the regulation of academic behaviors.

There is a very close relationship between people's sense of relatedness, or secure attachment, and autonomy support. Ryan and Lynch (1989) found that adolescents who experienced their parents as accepting and noncontrolling were those who felt securely attached. In a more recent examination of within-person, cross-relationship variations in security of attachment, La Guardia, Ryan, Couchman, and Deci (2000) found that autonomy support was crucial to feeling securely attached or intimately related. Indeed, many studies support this connection, which itself is proposed in theories of attachment. As Bretherton (1987) argues, “In the framework of attachment theory, maternal respect for the child's autonomy is an aspect of sensitivity to the infant's signals” (p. 1075). Within SDT, this connection between autonomy support and intimacy is viewed as a lifelong dynamic, one evident across diverse cultures (Lynch, LaGuardia, & Ryan, 2009).

Research also indicates that perceived competence is important to the internalization of extrinsically motivated behaviors. Individuals who feel efficacious in performing an activity are more likely to adopt it as their own, and conditions that support the development of relevant skills, by offering optimal challenges and effectance-relevant feedback, facilitate internalization (Deci & Ryan, 2000). This analysis also suggests that activities that are too difficult for an individual to perform—those that demand a level of physical or psychological maturation that a child has not reached, for example—will likely be externally regulated or introjected at best.

Internalization also depends on supports for autonomy. Contexts that use controlling strategies such as salient rewards and punishments or evaluative, self-esteem-hooking pressures are least likely to lead people to value activities as their own. This is not to say that controls don't work to produce behavior—decades of operant psychology prove that they can. It is rather that the more salient the external control over a person's behavior, the more the person is likely to be merely externally regulated or introjected in his or her actions. Consequently, the person does not develop a value or investment in the behaviors, but instead remains dependent on external controls. Thus, parents who reward, force, or cajole their child to do homework are more likely to have a child who does so only when rewarded, cajoled, or forced. The salience of external controls undermines the acquisition of self-responsibility. Alternatively, parents who supply reasons, empathize with difficulties overcoming obstacles, and use a minimum of external incentives are more likely to foster a sense of willingness and value for work in their child (Grolnick & Apostoleris, 2002).

The internalization process depicted in Figure 9.1 can end at various points, and social contexts can facilitate or undermine the relative autonomy of an individual's motivation along this continuum. For instance, a teenager might initially introject the need to act a certain way in an attempt to enhance or maintain relatedness to a parent who values it. However, depending on how controlling or autonomy-supportive the context is, that introjection might evolve upward toward greater self-acceptance or integration, or downward toward external regulation. Similarly, a person who finds a behavior valuable and important, that is, regulated by identification, may, if contexts become too demanding, begin to feel incompetent and fall into amotivation.

The more integrated an extrinsic regulation, the more a person is consciously aware of the meaning and worth inherent in the conduct of a behavior and has found congruence, or an integral “fit” between that behavior and other behaviors in his or her repertoire. Integrated regulation reflects a holistic processing of circumstance and possibilities (Kuhl & Fuhrmann, 1998; Ryan & Rigby, in press; Weinstein, Przybylski, & Ryan, 2013) and is facilitated by a perceived sense of choice, volition, and freedom from social and situational controls to think, feel, or act in a particular way. It is also facilitated by the provision of meaning for an extrinsic action—a nonarbitrary rationale for why something is important. Such supports for autonomy encourage the active endorsement of values, perceptions, and overt behaviors as the individual's own and are essential to identified or integrated behavioral regulation.

A number of laboratory and field research studies provide support for this theorizing and concrete examples of the integrative process described here. An experimental study by Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, and Leone (1994) showed that offering a meaningful rationale for an uninteresting behavior, in conjunction with supports for autonomy and relatedness, promoted internalization and integration. Grolnick and Ryan (1989) found that parents who were autonomy-supportive of their children's academic goals but also positively involved and caring fostered greater internalization of those goals and better teacher- and student-rated self-motivation. These and related findings have implications for efforts aimed at enhancing student motivation (see also Grolnick & Apostoleris, 2002; Vallerand, 1997).

The role of supportive versus undermining conditions also has practical significance in the fields of health care and psychotherapy, in which issues of compliance with and adherence to treatment are of great concern, not only to frontline care providers with a vested interest in patients' health, but also to those attentive to the financial and other consequences associated with treatment (non)compliance. For example, Williams, Rodin, Ryan, Grolnick, and Deci (1998) found that patients who were more likely to endorse statements such as “My doctor listens to how I would like to do things” showed better adherence to prescription medication regimens than patients who regarded their physicians as more controlling of their treatment plans. The patients' own autonomous motivation for medication adherence mediated the relation between perception of physician autonomy support and actual adherence.

The theoretical perspective of SDT also finds convergence with clinical practices emphasized in Miller and Rollnick's (2002) Motivational Interviewing. Several investigators have suggested that some of the demonstrated clinical efficacy of motivational interviewing reflects the importance of this strategy's synergistic emphasis on autonomy support, relatedness, and competency building (e.g., Markland, Ryan, Tobin, & Rollnick, 2005).

Facilitating Autonomous Regulation From the Inside

To date, work on the promotion of autonomous functioning has been largely devoted to an examination of social contextual factors. That is, SDT has been preoccupied with the social psychology of motivation, or how supports for autonomy, competence, and relatedness facilitate self-motivation. Of equal importance is how processes within the psyche are associated with the promotion of autonomous regulation and how these processes can be facilitated. It is clear that even when environments provide an optimal motivational climate, autonomous regulation requires both an existential commitment to act congruently, as well as the cultivation of the potential possessed by almost everyone to reflectively consider their behavior and its fit with personal values, needs, and interests (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). We next discuss recent research on the role that internal resources centered in consciousness and pertaining to awareness can play in fostering more autonomous regulation. Discussion of this new research focuses particularly on the concept of mindfulness.

A number of influential organismic and cybernetic theories of behavioral regulation place central emphasis on attention, the capacity to bring consciousness to bear on events and experience as they unfold in real time (e.g., Carver & Scheier, 1981; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991). These perspectives agree that the power of awareness and attention lies in bringing to consciousness information and sensibilities necessary for healthy self-regulation to occur. The more fully an individual is apprised of what is occurring internally and in the environment, the more healthy, adaptive, and value-consistent his or her behavior is likely to be.

Just as social forces can both inhibit and enhance healthy behavioral regulation, so too can factors associated with the enhancement or diminishment of attention and awareness. As a regulatory tool, our usual day-to-day state of attention is limited in two important ways that have cognitive and motivational bases. First, the usual reach of attention is quite restricted. Under normal circumstances, we are consciously aware of only a small fraction of our perceptions and actions (Varela et al., 1991). Evidence for such attentional limits comes from research on automatic or implicit processes. Automatic cognitive and behavioral processes are those that are activated and guided without conscious awareness. Accumulating research shows that much of our cognitive, emotional, and overt behavioral activity is automatically driven (Bargh, 1997).

The second way in which attention is limited pertains to its motivated selectivity. Among the information that is allowed into awareness, a high priority is placed on that which is relevant to the self, with the highest priority given to information that is relevant to self-preservation, in both biological and psychological terms. In developed societies, where threats to the biological organism are not usually at the forefront of concern, self-concept preservation is a primary motivation, within which is implicated our general tendency to evaluate events and experiences as good or bad for the self (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Langer, 2002). Reviewing the self-regulation literature, Baumeister, Heatherton, and Tice (1994) noted that, in general, individuals give relatively low priority to accurate self-knowledge. Instead, they pay most attention to information that enhances and validates the self-concept. The invested nature of attention can thus lead to the defensive redirection of attention away from phenomena that threaten the concept of self.

Both attentional limits and selectivity biases can have adaptive value in many circumstances, but they also can hinder optimal regulation of behavior. Information we do not want to be conscious of can be actively and conveniently displaced from focal attention and even from the wider field of awareness, in favor of other information more agreeable to the self. Attentional limits and biases provide ripe conditions for compartmentalization or fracturing of the self, wherein some aspects of self are placed on the stage of awareness and play a role in an individual's behavior, whereas others are actively kept backstage, out of the spotlight of attention. For purposes of behavioral regulation, the cost of such motivated attentional limits and biases lies in the controlled nature of behavior that can result, in which the aim is to remain responsive to internal and external forces or pressures toward ego-enhancement and preservation, rather than the sense of valuing, interest, and enjoyment that characterizes autonomous functioning. An ego-invested motivational orientation uses attention to select and shape experiences or distort them in memory in a way that defends and protects against ego-threat and clings to experiences or an interpretation of them that affirms the ego (e.g., Brown, Ryan, Creswell, & Niemiec, 2008; Hodgins & Knee, 2002). The self-centered use of attention outlined here hinders the openness to events and experience that could allow for an integration of self-aspects that could permit fuller, more authentic functioning.

Mindfulness and the Enhancement of Behavioral Regulation

The limits and biases of attention discussed here are not immutable. Regarding automatic processes, research has provided a detailed cognitive specification of the conditions under which behavior can be implicitly triggered (see Bargh & Ferguson, 2000). But research has also begun to show how such behavior can be modified or overridden (e.g., Dijksterhuis & van Knippenberg, 2000; Macrae & Johnston, 1998). Ample evidence indicates that the enactment of automatic, habitual behavior depends on a lack of attention to one's behavior and the cues that activate it. As Macrae and Johnston note, habitual action can unfold when the “lights are off and nobody's home.” Similarly, automatic thought patterns thrive while they remain out of the field of awareness (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002).

Conversely, there is evidence to indicate that enhanced attention and awareness can interfere with the development and unfoldment of automatic, habitual responses. An early demonstration was provided by Hefferline, Keenan, and Harford (1959). Using a conditioning paradigm in which individuals were reinforced for a subtle hand movement, they demonstrated that those who were unaware that conditioning was taking place showed the fastest rates of learning. Individuals who were told in a vague way that they were being conditioned showed slower learning of the response. Those who were explicitly instructed to learn the movement response that was being reinforced displayed the slowest learning. Thus, the more conscious individuals were of the conditioning, the more difficult was the development of automatized behavior. More recently, Dijksterhuis and van Knippenberg (2000) compared the ease with which stereotypes about politicians, college professors, and soccer hooligans could be activated through priming, depending on whether subjects' attention to the prime-response situation and awareness of themselves in that situation were induced. Heightened attention and self-awareness were shown to override the behavioral effects of activation of all three stereotypes examined. Evidence also suggests that the enhancement of awareness through training can intervene between the initial activation of an implicit response and the consequences that would typically follow. For example, Gollwitzer (1999) describes research showing that individuals who were made aware of their automatic stereotypic reactions to elderly people and then trained to mentally counteract them when they arose through implementation intentions no longer showed an automatic activation of stereotypic beliefs.

Collectively, this research suggests that attention, when brought to bear on present realities, can introduce an element of self-direction in what would otherwise be nonconsciously regulated, controlled behavior. But if behavior is to be regulated in a self-directed or self-endorsed manner on an ongoing, day-to-day basis, a dispositionally elevated level of attention and awareness would seem essential. Several forms of trait self-awareness have been examined over the years, including self-consciousness (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Buss, 1975) and reflection (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999), but such “reflexive consciousness” constructs (Baumeister, 1999) reflect cognitive operation on the contents of consciousness, rather than a perceptual sensitivity to the mind's contents. Neither are they designed to tap attention to and awareness of an individual's behavior and ongoing situational circumstances.

Mindfulness

Deci and Ryan (1980) suggested that a quality of consciousness termed mindfulness can act as an ongoing conscious mediator between causal stimuli and behavioral responses to them, leading to dispositional resistance to shifts away from self-determined, autonomous functioning in the presence of salient primes and other behavioral controls. A decade ago, we began an intensive investigation of mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Although there is no single definition of mindfulness (Anālayo, 2014), the concept commonly concerns an open or receptive awareness of and attention to what is taking place in the present moment (Brown & Ryan, 2003). It has similarly been described in classical Buddhist scholarship as “an alert but receptive equanimous observation” (Anālayo, 2003, p. 60) and as “watchfulness, the lucid awareness of each event that presents itself on the successive occasions of experience” (Bodhi, 2011, p. 21). The construct has a long pedigree, having been discussed for centuries in Buddhist philosophy and psychology and more recently in Western psychology (e.g., Kabat-Zinn, 2013; Langer, 1989; Linehan, 1993; Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995). Aside from the apparent role of present attention and awareness in the “de-automatization” of behavior (Safran & Segal, 1990), Wilber (2000) notes that bringing this quality of consciousness to bear on facets of the self and its experience that have been alienated, ignored, or distorted is theorized by a number of personality traditions to convert “hidden subjects” into “conscious objects” that can be differentiated from, transcended, and integrated into the self. In this sense, the quality of consciousness that is mindfulness conduces to the view that “all the facts are friendly,” which Rogers (1961, p. 25) believed necessary for “full functioning.”

As a monitoring function, mindfulness creates a mental gap between the “I,” or self (cf., James, 1890/1999), and the contents of consciousness (thoughts, emotions, and motives), one's behavior, and the environment. One consequence of this observant stance, we argue, is enhanced self-awareness and the provision of a window of opportunity to choose the form, direction, and other specifics of action—that is, to act in an autonomous manner.

Evidence for the role of mindfulness in the autonomous regulation of behavior comes from several studies. For example, using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) to assess a basic form of “mindful presence,” Brown and Ryan (2003) examined the role of mindfulness in facilitating autonomous behavior in daily life. The authors asked students and working adults to complete the MAAS and then to record the relative autonomy of their behavior (based on the conceptual model in Figure 9.1) at the receipt of a pager signal. This occurred three times a day on a quasirandom basis over a 2-week (students) or 3-week (adults) period. In both groups, higher scores on the MAAS predicted higher levels of autonomous behavior on a day-to-day basis.

This study also included a state measure of mindfulness. Participants specifically rated how attentive they were to the activities that had also been rated for their relative autonomy. Individuals who were more mindfully attentive to their activities also experienced more autonomous motivation to engage in those activities. The effects of trait and state mindfulness on autonomy were independent in this study, indicating that the regulatory benefits of mindfulness were not limited to those with a mindful disposition. The fact that state mindfulness and autonomous behavior were correlated in these samples bears some similarity to the intrinsically motivated autotelic, or “flow” experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997), in which awareness and action merge. In fact, Csikszentmihalyi (1997) suggests that key to the autotelic personality is the individual's willingness to be present to his or her ongoing experience.

This view of the human capacity for autonomy stands in contrast to the position that most behavior is automatically driven and that conscious will may be illusory (e.g., Wegner, 2002). Although, as we noted, it is clear that much behavior is automatic, we believe this issue is more complex than it may appear (see Ryan, Legate, Niemiec, & Deci, 2012). Although automatic processes may activate behaviors in any given moment, we contend that mindfulness of motives and the actions that follow from them can lead to an overriding or redirection of such processes (see also Bargh, 1997; Deci, Ryan, Schultz, & Niemiec, in press).

For example, Levesque and Brown (2007) examined whether mindfulness could shape or override the behavioral effects of implicit, low levels of autonomy. As with other motivational orientations, such as achievement, intimacy, and power (McClelland, Koestner, & Weinberger, 1989), Levesque and Brown (2007) hypothesized that individuals would differ not only in self-attributed relative autonomy but also in the extent to which they implicitly or nonconsciously associate themselves with autonomy. Using the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998) to assess relative levels of implicit autonomy, Levesque and Brown (2007) found that MAAS-measured dispositional mindfulness moderated the degree to which implicit relative autonomy predicted day-to-day autonomy, as measured through experience-sampling. Specifically, among less mindful individuals, implicit-relative autonomy positively predicted day-to-day motivation for behavior. Among such persons, those who implicitly associated themselves with control and pressure manifested the same kind of behavioral motivation in daily life, whereas individuals with high levels of implicit autonomy behaved in accord with this automatic self-association. However, among more mindful individuals, the relation between the automatic motivational association and daily behavior was null. Mindfulness thus served an overriding functioning, such that it facilitated self-endorsed behavior, regardless of the type of implicit motivational tendency that individuals held.

Similarly, in a series of experimental studies, Niemiec et al. (2010) demonstrated that persons higher in mindfulness did not show the kind of defensive reactions reliably observed when people are threatened with mortality salience stimuli. Whereas less mindful individuals were ready to derogate out-group members when under threat, more mindful persons did not, in part because they more fully processed the threat experience.

In this vein, it is important to note that the effect of mindfulness lies not necessarily in creating psychological experiences, many of which are conditioned phenomena (Wegner, 2002) that arise spontaneously (Dennett, 1984), but in allowing for choicefulness in whether to endorse or veto the directives that consciousness brings to awareness, thereby permitting the direction of action toward self-endorsed ends (Libet, 1999; Ryan et al., 2012). Indeed, by definition, self-endorsement requires a consciousness of one's needs or values and the role of anticipated action in meeting or affirming them (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Relatedly, an individual may be aware of several competing motives at a given time, all of which cannot be satisfied. Mindfulness creates an opportunity for choices to be made that maximize the satisfaction of needs and desires within the parameters of the situation at hand (Deci & Ryan, 1980).

Mindfulness appears not only to foster self-endorsed activity at the level of day-to-day behavior, but also to encourage the adoption of higher order goals and values that reflect healthy regulation. Kasser and colleagues (e.g., Kasser & Ryan, 1996; Kasser, Chapter 6, this volume) have shown that intrinsic values—for personal development, affiliation, and community contribution, for example—have an inherent relationship to basic psychological need satisfaction; that is, they directly fulfill needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Extrinsic values, in contrast, including aspirations for wealth, popularity, and personal image, are pursued for their instrumental value and typically fulfill basic needs only indirectly, at best. Moreover, extrinsic goals are often motivated by introjected pressures or external controls (Kasser, 2002). Accordingly, accumulating research indicates that the relative centrality of intrinsic and extrinsic values has significant consequences for subjective well-being, risk behavior, and other outcomes (see Kasser, Chapter 6, this volume). It is thus noteworthy that recent research has shown that mindfulness is associated with a stronger emphasis on intrinsic aspirations, and this values orientation is in turn related to indicators of subjective well-being and healthy lifestyle choices (Brown & Kasser, 2005). Although mindfulness directly predicts higher well-being (see Brown, Creswell, & Ryan, in press), this research also shows that its salutary effects come by facilitating self-regulation.

Cultivating Mindfulness

Research conducted over the past 35 years indicates that mindfulness can be enhanced through training (Brown et al., in press). In such training, individuals learn, through daily practice, to sharpen their inherent capacities to attend to and be aware of presently occurring internal, behavioral, and environmental events and experience. Mindfulness training is associated with a variety of lasting positive psychological and somatic well-being outcomes (see Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010). Research has begun to show that such training may conduce to more self-determined behavior. For example, Brown, Kasser, Ryan, Linley, and Orzech (2009) found that meditation training-related increases in mindfulness, as assessed by two self-report measures (including the MAAS), were related to declines in wealth-related desires. Recently, Kirk, Brown, and Downer (2014) found that individuals trained in mindfulness meditation showed neural evidence of lower susceptibility to monetary rewards. Using the Monetary Incentive Delay task (Knutson, Adams, Fong, & Hommer, 2001) while undergoing functional brain imaging, mindfulness trainees and matched controls performed equally well on the task, but the meditators showed lower neural activations in brain regions involved in reward processing—both during monetary gain and loss anticipation and receipt—indicating that the former were less susceptible to monetary incentives but without task performance costs. Such training-related reduced susceptibilities to a powerful extrinsic reward may foster enhanced behavioral regulation, a proposition to be tested in future research.

Conclusion

This chapter has attempted to demonstrate that autonomous regulation of inner states and overt behavior is key to a number of positive outcomes that reflect healthy behavioral and psychological functioning. The practical value of autonomy has been demonstrated through research in a number of important life domains, including child development and education, health behavior, sport and exercise, and others. Decades of research also show that when people act autonomously, whether motivated intrinsically or extrinsically through more internalized and integrated regulation, their quality of action and sense of well-being benefits.

Judgment as to the practical utility of research on autonomy relies on evidence that this regulatory style can be promoted. We have shown here that autonomy can be facilitated both from without—through social supports—and from within, through the receptive attention and awareness to present experience that helps to characterize mindfulness. Although significant in themselves, these two sources of support are not necessarily separate and may, in fact, interact to enhance autonomous regulation. For example, an individual in a position to influence the motivation of another person or group may do so more effectively and positively when mindfulness about the effects of his or her communication style and behavior is present. Just as an individual seeking to change his or her regulatory style can benefit from greater awareness of self and attention to behavior, reason suggests that parents, teachers, supervisors, and others may draw on their own mindful capacities to facilitate the support of healthy, growth-promoting regulation in others.

Research reviewed here indicated that mindfulness can enhance self-knowledge and action that accords with the self, both of which are key to authentic action (Harter, 2002). Enhanced attention and awareness also appear to undermine the effects of past and present conditioning and the external control of behavior that it may entail. It might then be possible that a greater dose of mindfulness helps to inoculate individuals against social and cultural forces acting to inhibit or undermine choicefulness and the self-endorsement of values, goals, and behaviors. In fact, it may be difficult in today's society to live autonomously without mindfulness, considering the multitude of forces, internal and external, that often pull us in one direction or another. In a world where commercial, political, economic, and other messages seeking to capture attention, allegiance, and wallets have become ubiquitous, mindful reflection on the ways in which we wish to expend the limited resource of life energy that all of us are given seems more important than ever.

Summary Points

- Motivation varies according to the reasons or goals that energize behavior, and this “why” of behavior has significant emotional and intellectual consequences.

- Autonomously motivated or self-determined behavior is self-endorsed and done willingly, and promotes a variety of positive intrapersonal, interpersonal, and performance outcomes.

- Social supports for autonomy, both alone and when paired with relatedness (caring and acceptance) and the support of competence (e.g., providing optimal challenge), reliably foster autonomous behavior.

- Social supports for autonomy, competence, and relatedness also encourage the internalization and integration of behavior, thereby shifting it toward being autonomously regulated.

- Healthy behavior regulation is also facilitated by internal psychological supports, notably mindfulness.

- Mindfulness, a receptive attention to and awareness of ongoing events and experiences, can foster autonomously regulated behavior and self-endorsed, or intrinsic, goals and values.

- Training in mindfulness is associated with reduced susceptibility to extrinsic rewards that can undermine autonomy, and such training may thereby promote self-determined behavior and the manifold positive outcomes that attend it.

References

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context. New York, NY: Westview Press.

- Anālayo, B. (2003). Satipatthāna: The direct path to realization. Birmingham, England: Windhorse.

- Anālayo, B. (2014). Mindfulness in early Buddhism. Unpublished manuscript, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

- Baard, P. P., & Aridas, C. (2001). Motivating your church: How any leader can ignite intrinsic motivation and growth. New York, NY: Crossroad.

- Bargh, J. A. (1997). Automaticity in social psychology. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 169–183). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Bargh, J. A., & Ferguson, M. J. (2000). Beyond behaviorism: On the automaticity of higher mental processes. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 925–945.

- Baumeister, R. F. (1999). The nature and structure of the self: An overview. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), The self in social psychology (pp.1–20). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1994). Losing control: How and why people fail at self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Bodhi, B. (2011). What does mindfulness really mean? A canonical perspective. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 19–39.

- Bowlby, J. (1979). The making and breaking of affectional bonds. London, England: Tavistock.

- Bretherton, I. (1987). New perspectives on attachment relations: Security, communication and internal working models. In J. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development (pp. 1061–1100). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Brown, K. W., Creswell, J. D., & Ryan, R. M. (Eds.). (in press). Handbook of mindfulness: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research, 74, 349–368.

- Brown, K. W., Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Linley, P. A., & Orzech, K. (2009). When what one has is enough: Mindfulness, desire discrepancies, and subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 727–736.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

- Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., Creswell, J. D., & Niemiec, C. P. (2008). Beyond me: Mindful responses to social threat. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending self-interest: Psychological explorations of the quiet ego (pp. 75–84). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). Attention and self-regulation: A control theory approach to human behavior. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Chandler, C. L., & Connell, J. P. (1987). Children's intrinsic, extrinsic and internalized motivation: A developmental study of children's reasons for liked and disliked behaviors. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5, 357–365.

- Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., & Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 97–109.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- DeCharms, R. (1968). Personal causation. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., & Leone, D. R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62, 119–142.

- Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627–668.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1980). Self-determination theory: When mind mediates behavior. Journal of Mind and Behavior, 1, 33–43.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1995). Human autonomy: The basis for true self-esteem. In M. Kernis (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem (pp. 31–49). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 85–107). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Schultz, P. P., & Niemiec, C. P. (in press). Being aware and functioning fully: Mindfulness and interest-taking within self-determination theory. In K. W. Brown, J. D. Creswell, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Dennett, D. (1984). Elbow room: The varieties of free will worth wanting. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 355–391.

- Dijksterhuis, A. P., & van Knippenberg, A. D. (2000). Behavioral indecision: Effects of self-focus on automatic behavior. Social Cognition, 18, 55–74.

- Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 522–527.

- Frodi, A., Bridges, L., & Grolnick, W. S. (1985). Correlates of mastery-related behavior: A short-term longitudinal study of infants in their second year. Child Development, 56, 1291–1298.

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54, 493–503.

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464–1480.

- Grolnick, W. S., & Apostoleris, N. H. (2002). What makes parents controlling. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 161–181). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children's self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 143–154.

- Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43.

- Harter, S. (2002). Authenticity. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 382–394). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Hefferline, R. F., Keenan, B., & Harford, R. A. (1959). Escape and avoidance conditioning in human subjects without their observation of the response. Science, 130, 1338–1339.

- Hodgins, H. S., & Knee, C. R. (2002). The integrating self and conscious experience. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 87–100). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 169–183.

- James, W. (1890/1999). The self. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), The self in social psychology (pp. 9–77). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

- Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., & Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriented Korean students? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 644–661.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Bantam.

- Kasser, T. (2002). Sketches for a self-determination theory of values. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 123–140). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280–287.

- Kirk, U., Brown, K. W., & Downer, J. (2014). Mindfulness practitioners show attenuated neural activation to incentive delay: Evidence from brain imaging. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Knutson, B., Adams, C. M., Fong, G. W., & Hommer, D. (2001). Anticipation of increasing monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accembens. Journal of Neuroscience, 21, RC159.

- Kuhl, J., & Fuhrmann, A. (1998). Decomposing self-regulation and self-control. In I. Heckhausen & C. Dweck (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulation across the life span (pp. 15–49). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- La Guardia, J. G., & Patrick, H. (2008). Self-determination theory as a fundamental theory of close relationships. Canadian Psychology, 49, 201–209.

- La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 367–384.

- Langer, E. (1989). Mindfulness. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Langer, E. (2002). Well-being: Mindfulness versus positive evaluation. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 214–230). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Levesque, C. S., & Brown, K. W. (2007). Overriding motivational automaticity: Mindfulness as a moderator of the influence of implicit motivation on day-to-day behavior. Motivation and Emotion, 31, 284–299.

- Libet, B. (1999). Do we have free will? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6, 47–57.

- Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Lynch, M. F., La Guardia, J. G., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). On being yourself in different cultures: Ideal and actual self-concept, autonomy support, and well-being in China, Russia, and the United States. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 290–304.

- Macrae, C. N., & Johnston, L. (1998). Help, I need somebody: Automatic action and inaction. Social Cognition, 16, 400–417.

- Markland, D., Ryan, R. M., Tobin, V., & Rollnick, S. (2005). Motivational interviewing and Self-Determination Theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24, 811–831.

- McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96, 690–702.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Murayama, K., Matsumoto, M., Izuma, K., Sugiura, A., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. & Matsumoto, K. (in press). How self-determined choice facilitates performance: A key role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. doi:10.1093/cercor/bht317

- Niemiec, C. P., Brown, K. W., Kashdan, T. B., Cozzolino, P. J., Breen, W. E., Levesque-Bristol, C., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Being present in the face of existential threat: The role of trait mindfulness in reducing defensive responses to mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 344–365. doi:10.1037/a0019388

- Pelletier, L. G. (2002). A motivational analysis of self-determination for pro-environmental behaviors. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 205–232). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Reeve, J., Bolt, E., & Cai, Y. (1999). Autonomy-supportive teachers: How they teach and motivate students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 537–548.

- Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2011). Glued to games: The attractions, promise and perils of video games and virtual worlds. New York, NY: Praeger.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Ryan, R. M. (1982). Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 450–461.

- Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63, 397–427.

- Ryan, R. M., Bernstein, J. H., & Brown, K. W. (2010). Weekends, work, and wellbeing: Psychological need satisfactions and day of the week effects on mood, vitality, and physical symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 95–122. doi:10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.95

- Ryan, R. M., & Brown, K. W. (2003). Why we don't need self-esteem: On fundamental needs, contingent love, and mindfulness. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 71–76.

- Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 749–761.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic, motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Autonomy is no illusion: Self-determination theory and the empirical study of authenticity, awareness, and will. In J. Greenberg, S. Koole, & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 449–479). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Ryan, R. M., Koestner, R., & Deci, E. L. (1991). Ego-involved persistence: When free-choice behavior is not intrinsically motivated. Motivation and Emotion, 15, 185–205.

- Ryan, R. M., Legate, N., Niemiec, C. P., & Deci, E. L. (2012). Beyond illusions and defense: Exploring the possibilities and limits of human autonomy and responsibility through self-determination theory. In P. R. Shaver & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), Meaning, mortality, and choice: The social psychology of existential concerns (pp. 215–233). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Ryan, R. M., & Lynch, J. (1989). Emotional autonomy versus detachment: Revisiting the vicissitudes of adolescence and young adulthood. Child Development, 60, 340–356.

- Ryan, R. M., Patrick, H., Deci, E. L. & Williams, G. C. (2008). Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on Self-Determination Theory. European Health Psychologist, 10, 1–4.

- Ryan, R. M., & Rigby, C. S. (in press). Did the Buddha have a self? No-self, self and mindfulness in Buddhist thought and western psychologies. In K. W. Brown, J. D. Creswell, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Ryan, R. M., Stiller, J., & Lynch, J. H. (1994). Representations of relationships to teachers, parents, and friends as predictors of academic motivation and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence, 14, 226–249.

- Safran, J. D., & Segal, Z. V. (1990). Interpersonal process in cognitive therapy. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Segal, Z., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Kim, Y., & Kasser, T. (2001). What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 325–339.

- Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z., & Williams, J. M. G. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behavior Research and Therapy, 33, 25–39.

- Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 284–304.

- Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 271–360). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Vallerand, R. J., & Reid, G. (1984). On the causal effects of perceived competence on intrinsic motivation: A test of cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Sport Psychology, 6, 94–102.

- Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. doi:10.1037/a0032359

- Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wegner, D. M. (2002). The illusion of conscious will. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Weinstein, N., Przybylski, A. K., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). The integrative process: New research and future directions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 69–74.

- Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

- Williams, G. C., Rodin, G. C., Ryan, R. M., Grolnick, W. S., & Deci, E. L. (1998). Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychology, 17, 269–276.

- Zuroff, D. C., Koestner, R., Moskowitz, D. S., McBride, C., Marshall, M., & Bagby, M. (2007). Autonomous motivation for therapy: A new common factor in brief treatments for depression. Psychotherapy Research, 17, 137–147.