Chapter 42

Happiness as a Priority in Public Policy

RUUT VEENHOVEN

Introduction

Attempts to improve the human lot begin typically with treating compelling miseries, such as hunger and epidemics. When these problems are solved, attention shifts to broader and more positive goals; we can see this development in the history of social policy, the goal of which has evolved from alleviating poverty to providing a decent standard of living for everybody. The field of medicine has witnessed a similar shift from assisting people to survive to, in addition, promoting a good quality of life. This policy change has put some difficult questions back on the agenda, such as “What is a good life?” and “What good is the best?” The social sciences cannot provide good answers to these questions, since they have also focused on misery. Yet, a good answer can be found in a classic philosophy, and it is one that is worth reconsidering.

The Greatest Happiness Principle

Two centuries ago Jeremy Bentham (1789) proposed a new moral principle. He wrote that the goodness of an action should not be judged by the decency of its intentions, but by the utility of its consequences. Bentham conceived final utility as human happiness. Hence, he concluded that we should aim at the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Bentham defined happiness in terms of psychological experience, as “the sum of pleasures and pains.” This philosophy is known as utilitarianism, because of its emphasis on the utility of behavioral consequences. Happyism would have been a better name, since this utility is seen as contribution to happiness.

When applied at the level of individual choice, this theory runs into some difficulties. Often, we cannot foresee what the balance of effects on happiness will be. In addition the theory deems well-intended behavior to be amoral if it happens to pan out adversely. Imagine the case of a loving mother who saves the life of her sick child, a child who grows up to be a criminal; mothers can seldom foresee a child's future and can hardly be reproached for their unconditional motherly love.

The theory is better suited for judging general rules, such as the rule that mothers should care for their sick children. It is fairly evident that adherence to this rule will add to the happiness of a great number. Following such rules is then morally correct, even if consequences might be negative in a particular case. This variant is known as rule-utilitarianism.

Rule-utilitarianism has been seen as a moral guide for legislation and has played a role in discussions about property laws and the death penalty. The principle can also be applied to wider issues in public policy, such as the question of what degree of income inequality we should accept. The argument is that inequality is not bad in and of itself; it is only so if it reduces the happiness of the average citizen. The greatest happiness principle can also be used when making decisions about health care and therapy. Treatment strategies can be selected on the basis of their effects on the happiness of the greatest number of patients.

Objections Against the Principle

The greatest happiness principle is well-known, and it is a standard subject in every introduction to moral philosophy. Yet the principle is seldom put into practice. Why is this? The answer to this question is also to be found in most introductory philosophy books: Utilitarianism is typically rejected on pragmatic and moral grounds.

Pragmatic Objections

Application of the greatest happiness principle requires that we know what happiness is and that we can predict the consequences of behavioral alternatives on it. It also requires that we can check the results of applying this principle; that is, we can measure resulting gains in happiness. At a more basic level, the principle assumes that happiness can be affected by what we do. All of this is typically denied. It is claimed that happiness is an elusive concept and one that we cannot measure. As a consequence, we can only make guesses about the effects of happiness on behavioral alternatives and can never verify our suppositions. Some even see happiness as an immutable trait that cannot be influenced. Such criticism often ends with the conclusion that we would do better to stick to more palpable seasoned virtues, such as justice and equality.

Moral Objections

Another objection is that happiness is mere pleasure or an illusionary matter and hence not very valuable in and of itself. It is, therefore, not considered as the ultimate ethical value. Another moral objection is that happiness spoils; in particular, it fosters irresponsible consumerism and makes us less sensitive to the suffering of others. Still another objection holds that the goal of advancing happiness justifies amoral means, such as genetic manipulation, mind control, and dictatorship. Much of these ethical qualms are featured in Huxley's (1932) Brave New World.

Plan of This Chapter

The preceding discussion is armchair theorizing, mainly by philosophers and novelists. How do these objections stand up to empirical tests? I first introduce modern empirical research on happiness, then consider the qualms mentioned previously in the light of the findings.

Research on Happiness

Empirical research on happiness started in the 1960s in several branches of the social sciences. In sociology, the study of happiness developed from social indicators research. In this field, subjective indicators were used to supplement traditional objective indicators, and happiness became a main subjective indicator of social system performance (Andrews & Withey, 1976; Campbell, 1981).

In psychology, the concept was used in the study of mental health. Jahoda (1958) saw happiness as a criterion for positive mental health, and items on happiness figured in the pioneering epidemiological surveys on mental health by Gurin, Veroff, and Feld (1960) and Bradburn and Caplovitz (1965). At that time, happiness also figured in the groundbreaking cross-national study of human concerns by Cantril (1965) and came to be used as an indicator of successful aging in gerontology (Neugarten, Havighurst, & Tobin, 1961). Twenty years later, the questionnaires on health related to quality of life, such as the much-used SF-36 (Ware, 1996). Since 2000, economists such Frey and Stutzer (2002) have also picked up the issue and a first institute of happiness economics has been established.1

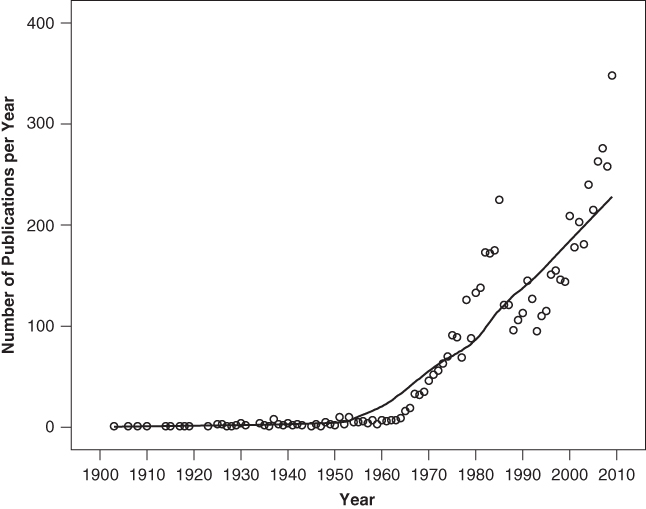

Most empirical studies on happiness are based on large-scale population surveys, but there are also many studies of specific groups, such as single mothers, students, or lottery winners. The bulk of these studies revolve around one-time questionnaire studies, but there are a number of follow-up studies and even some experimental studies. To date, some 7,000 research reports have been published, and the number of publications is increasing exponentially, as shown in Figure 42.1.

Figure 42.1 Rise of publications on happiness.

Source: World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2013a).

The study of happiness has been institutionalized rapidly over the past few years. Most investigators have joined forces and formed the International Society for Quality of Life Studies (ISQOLS).2 The topic is central in the Journal of Happiness Studies3 and in the International Journal of Happiness and Development4 and prominent in several other scientific journals on subjective well-being. The findings from this strand of research are gathered in the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013a).

This collaboration has created a considerable body of knowledge, which I use in the following discussion to determine the reality value of philosophical objections against the greatest happiness principle.

Is Happiness a Practicable Goal?

Pragmatic objections against the greatest happiness principle are many. The most basic objection is that happiness cannot be defined; therefore, all talk about happiness is mere rhetoric. The second objection is that happiness cannot be measured, so we can never establish an absolute degree and number for happiness. A third objection holds that lasting happiness of a great number is not possible; at best, we can find some relief in fleeting moments of delusion. The last claim is that we cannot bring about happiness. I next discuss these objections individually.

Can Happiness Be Defined?

The word happiness has different meanings, and these meanings are often mixed up, which gives the concept a reputation for being elusive. Yet, a confusion of tongues about a word does not mean that no substantive meaning can be defined. Let us consider what meanings are involved and which of these is most appropriate as an end goal.

Four Qualities of Life

When used in a broad sense, the word happiness is synonymous with quality of life or well-being. In this meaning, it denotes that life is good, but does not specify what is good about life. The word is also used in more specific ways, which can be clarified with the help of the classification of qualities of life presented in Table 42.1.

Table 42.1 Four Qualities of Life

| External | Internal | |

| Life chances | Livability of environment | Life-ability of the person |

| Life results | Usefulness of life | Satisfaction with life |

Source: Veenhoven (2000).

This classification of meanings depends on two distinctions. Vertically there is a difference between chances for a good life and actual outcomes of life. Chances and outcomes are related, but are certainly not the same. Chances can fail to be realized, because of stupidity or bad luck. Conversely, people sometimes make much of their life in spite of poor opportunities. This distinction is common in the field of public-health research. Preconditions for good health, such as adequate nutrition and professional care, are seldom confused with health itself. Yet means and ends are less well distinguished in the discussion on happiness.

Horizontally there is a distinction between external and internal qualities. In the first case the quality is in the environment; in the latter it is in the individual. Lane (2000) made this distinction clear by emphasizing “quality of persons.” This distinction is also commonly made in public health. External pathogens are distinguished from inner afflictions, and researchers try to identify the mechanisms by which the former produce the latter and the conditions in which this is more or less likely. Yet again this basic insight is lacking in many discussions about happiness.

Together, these two dichotomies mark four qualities of life, all of which have been denoted by the word happiness.

Livability of the Environment

The top left quadrant of Table 42.1 denotes the meaning of good living conditions. Often the terms quality of life and well-being are used in this particular meaning, especially in the writings of ecologists and sociologists. Economists sometimes use the term welfare for this meaning. Livability is a better word, because it refers explicitly to a characteristic of the environment and does not carry the connotation of paradise. Politicians and social reformers typically stress this quality of life.

Lifeability of the Person

The top right quadrant denotes inner life-chances, that is, how well we are equipped to cope with the problems of life. This aspect of the good life is also known by different names. Especially doctors and psychologists use the terms quality of life and well-being to denote this specific meaning. There are more names, however. In biology the phenomenon is referred to as adaptive potential. On other occasions it is denoted by the medical term health, in the medium variant of the word.5 Sen (1993) calls this quality of life variant capability. I prefer the simple term lifeability, which contrasts elegantly with livability. This quality of life is central in the thinking of therapists and educators.

Usefulness of Life

The bottom left quadrant represents the notion that a good life must be good for something more than itself. This presumes some higher value, such as ecological preservation or cultural development. In fact, there are myriad values on which the utility of life can be judged. There is no current generic for these external turnouts of life. Gerson (1976) referred to these kinds as transcendental conceptions of quality of life. Another appellation is meaning of life, which then denotes true significance instead of mere subjective sense of meaning. I prefer the more simple utility of life, admitting that this label may also give rise to misunderstanding.6 Moral advisers, such as a pastor, emphasize this quality of life.

Satisfaction with Life

Finally, the bottom right quadrant represents the inner outcomes of life, that is, the quality in the eye of the beholder. As we deal with conscious humans, this quality boils down to subjective appreciation of life, commonly referred to by terms such as subjective well-being, life-satisfaction, and happiness in a limited sense of the word.7 Life has more of this quality, the more and the longer it is enjoyed. In fairy tales this combination of intensity and duration is denoted with the phrase “They lived happily ever after.” There is no professional interest group that stresses this meaning, and this seems to be one of the reasons for the reservations surrounding the greatest happiness principle.

Which of these four meanings of the word happiness is most appropriate as an end goal? I think the last one. Commonly policy aims at improving life-chances by, for example, providing better housing or education, as indicated in the upper half of Table 42.1. Yet more is not always better, and some opportunities may be more critical than others. The problem is that we need a criterion to assign priorities among the many life-chances policy makers want to improve. That criterion should be found in the outcomes of life, as shown in the lower half of Table 42.1. There, utility provides no workable criterion, since external effects are many and can be valued differently. Satisfaction with life is a better criterion, since it reflects the degree to which external living conditions fit with inner life-abilities. Satisfaction is also the subjective experience Jeremy Bentham had in mind.

Four Kinds of Satisfaction

This brings us to the question of what satisfaction is precisely. This is also a word with multiple meanings we can elucidate. Table 42.2 is based on two distinctions: The vertical distinction is between satisfaction with parts of life versus satisfaction with life-as-a-whole, the horizontal distinction between passing satisfaction and enduring satisfaction. These two bipartitions yield again a fourfold taxonomy.

Table 42.2 Four Kinds of Satisfaction

| Passing | Enduring | |

| Life aspects | Pleasure | Domain satisfaction |

| Life-as-a-whole | Peak experience | Life satisfaction |

Pleasure

Passing satisfaction with a part of life is called pleasure. Pleasures can be sensory, such as a glass of good wine, or mental, such as the reading of this text. The idea that we should maximize such satisfactions is called hedonism.

Part-Satisfactions

Enduring satisfaction with a part of life is referred to as part-satisfaction. Such satisfactions can concern a domain of life, such as working life, and aspects of life, such as its variety. Sometimes the word happiness is used for such part-satisfactions, in particular for satisfaction with your career.

Top Experience

Passing satisfaction can be about life-as-a-whole, in particular when the experience is intense and oceanic. This kind of satisfaction is usually referred to as top-experience. When poets write about happiness they usually describe an experience of this kind. Likewise, religious writings use the word happiness often in the sense of a mystical ecstasy. Another word for this type of satisfaction is enlightenment.

Life Satisfaction

Enduring satisfaction with your life-as-a-whole is called life-satisfaction and also commonly referred to as happiness. This is the kind of satisfaction Bentham seems to have had in mind when he described happiness as the “sum of pleasures and pains.” I have delineated this concept in more detail elsewhere, and defined it as “the overall appreciation of one's life-as-a-whole” (Veenhoven, 1984, pp. 22–23).

Life-satisfaction is most appropriate as a policy goal. Enduring satisfaction is clearly more valuable than passing satisfactions, and satisfaction with life-as-a-whole is also of more worth than mere part-satisfaction. Moreover, life-satisfaction is probably of greater significance, since it signals the degree to which human needs are being met. I return to this point later.

In sum, happiness can be defined as the overall enjoyment of your life as-a-whole.

Can Happiness Be Measured?

A common objection to the greatest happiness principle is that happiness cannot be measured. This objection applies to most of the previously discussed meanings of the word, but does it apply to happiness in the sense of life-satisfaction?

Happiness in this sense is a state of mind, which cannot be assessed objectively in the same way as weight or blood pressure. Happiness cannot be measured with access to merit-goods, since the effect of such life-chances depends on life-abilities. Though there is certainly a biochemical substrate to the experience, we cannot as yet measure happiness using physical indicators. The hedometer awaits invention. Extreme states of happiness and unhappiness manifest in nonverbal behavior, such as smiling and body posture, but these indications are often not well visible. This leaves us with self-reports. The question is then whether happiness can be measured adequately in this way.

Self-Reports

There are many reservations about self-report measures of happiness: People might not be able to oversee their lives, self-defense might distort the judgment, and social desirability could give rise to rosy answers. Thus, early investigators experimented with indirect questioning. Happiness was measured by a clinical interview, by content analysis of diaries and using projective methods such as the Thematic Apperception Test. These methods are laborious and their validity is not beyond doubt. Hence, direct questions have also been used from the beginning. A careful comparison of these methods showed that direct questioning yields the same information at a lower cost (Wessman & Ricks, 1966).

Direct Questionioning

Direct questions on happiness are often framed in larger questionnaires, such as the much-used 20-item Life Satisfaction Index (LSI) of Neugarten et al. (1961). There are psychometric advantages with the use of multiple-item questionnaires, in particular a reduction of error due to difference in interpretation of key words. Yet, a disadvantage is that most of the happiness inventories involve items that do not quite fit the concept defined previously. For instance, the LSI contains a question on whether the individual has plans for the future, which is clearly something other than enjoying current life.

The use of multiple items is common in psychological testing because the object of measurement is mostly rather vague. For example, neuroticism cannot be sharply defined and is therefore measured with multiple questions about matters that are likely to be linked to that matter. Yet, happiness is a well-defined concept (overall enjoyment of life-as-a-whole) and can, therefore, be measured by one question. Another reason for the use of multiple items in psychological measurement is that respondents are mostly unaware of the state to be measured. For instance, most respondents do not know how neurotic they are, so neuroticism is inferred from their responses to various related matters. Yet, happiness is something of which the respondent is conscious. Hence, happiness can also be measured by single direct questions, which is common practice and one that works.

Common Survey Questions

Because happiness can be measured with single direct questions, it has become a common item in large-scale surveys among the general population in many countries. A common question reads:

Taken all together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you currently with your life as a whole?

Many more question-and-answer formats have been used. All acceptable items are documented in full detail in the collection of happiness measures of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013d).

Validity

Though these questions are fairly clear, responses can be flawed in several ways. Responses may reflect how happy people think they should be rather than how happy they actually feel, and it is also possible that people present themselves as happier than they actually are. These suspicions have given rise to numerous validation studies. Elsewhere I have reviewed this research and concluded that there is no evidence that responses to these questions measure something other than what they are meant to measure (Veenhoven, 1984, Chapter 3; 1998). Though this is no guarantee that research will never reveal a deficiency, we can trust these measures of happiness for the time being.

Reliability

Research has also shown that responses are affected by minor variations in wording and ordering of questions and by situational factors, such as the race of the interviewer or the weather. As a result, the same person may score 6 in one investigation and 7 in another. This lack of precision hampers analyses at the individual level. It is less of a problem when average happiness in groups is compared, since random fluctuations tend to balance, typically the case when happiness is used in policy evaluation.

Comparability

The objection is made that responses on such questions are not comparable, because a score of 6 does not mean the same for everybody. A common philosophical argument for this position is that happiness depends on the realization of wants and that these wants differ across persons and cultures (Smart & Williams, 1973). Yet, it is not at all sure that happiness depends on the realization of idiosyncratic wants. The available data are more in line with the theory that it depends on the gratification of universal needs (Veenhoven, 1991, 2009). I will come back on this point in the later discussion on the signal function of happiness.

A second qualm is whether happiness is a typical Western concept that is not recognized in other cultures. Happiness appears to be a universal emotion that is recognized in facial expression all over the world (Ekman & Friesen, 1975) and for which words exist in all languages. A related objection is that happiness is a unique experience that cannot be communicated on an equivalent scale. Yet from an evolutionary point of view, it is unlikely that we differ very much. As in the case of pain, there will be a common human spectrum of experience.

Last, there is methodological reservation about possible cultural bias in the measurement of happiness, due to problems with translation of keywords and cultural variation in response tendencies. I have looked for empirical evidence for these distortions elsewhere, but did not find any (Veenhoven, 1993, Chapter 5). All these objections imply that research using these measures of happiness will fail to find any meaningful correlations. Later we see that this is not true.

In sum, happiness as life-satisfaction is measurable with direct questioning and well comparable across persons and nations. Hence, happiness of a great number can be assessed using surveys.

Is Happiness Possible?

Aiming at happiness for a great number has often been denounced as illusionary because long-term happiness, and certainly happiness for a great number, is a fantasy. This criticism has many fathers. In some religions the belief is that man has been expelled from Paradise: Earthly existence is not to be enjoyed; we are here to chasten our souls. Classic psychologists have advanced more profane reasons.

Freud (1929/1948) saw happiness as a short-lived orgasmic experience that comes forth from the release of primitive urges. Hence, he believed that happiness is not compatible with the demands of civilized society and that modern man is, therefore, doomed to chronic unhappiness. In the same vein, Adorno believed that happiness is a mere temporary mental escape from misery, mostly at the cost of reality control (Rath, 2002).

The psychological literature on adaptation is less pessimistic, but it, too, denies the possibility of enduring happiness for a great number. It assumes that aspirations follow achievements and, hence, concludes that happiness does not last. It is also inferred that periods of happiness and unhappiness oscillate over a lifetime, and the average level is, therefore, typically neutral. Likewise, social comparison is seen to result in a neutral average, and enduring happiness is possible only for a “happy few” (Brickman & Campbell, 1971).

Enduring Happiness

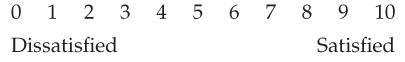

Figure 42.2 presents the distribution for responses to the 0-to-10-step question on life-satisfaction in the United States. The most frequent responses are between 7 and 10 and less than 5% scores below neutral. The average is 7.85.8 This result implies that most people must feel happy most of the time. That view has been corroborated by yearly follow-up studies over many years (Ehrhardt, Saris, & Veenhoven, 2000) and by studies that use the technique of experience sampling (Schimmack & Diener, 2003).

Figure 42.2 Life-satisfaction in the United States, 2007.

Source: Gallup World Poll (2007).

Happiness of a Great Number

The high level of happiness is not unique to the United States. Table 42.3 shows similar averages in other Western nations. In fact, average happiness tends to be above neutral in most countries of the world. So happiness for a great number is apparently possible.

Table 42.3 Life-Satisfaction in 12 Nations, 2000–2009

| Best | Middle | Worst | |||

| Costa Rica | 8.5 | South Korea | 6.0 | Benin | 3.0 |

| Denmark | 8.3 | Estonia | 6.0 | Burundi | 2.9 |

| Iceland | 8.2 | Tunisia | 5.9 | Tanzania | 2.8 |

| Switzerland | 8.0 | Turkey | 5.7 | Togo | 2.6 |

Note. Average scores on a 0–10 Scale.

Source: Happiness in Nations. World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013c).

Table 42.3 also shows that average happiness was below neutral in several African countries. All this is in flat contradiction to Freudian theory, which predicts averages below 4 everywhere and defies adaptation theory that predicts universal averages around 5.

Greater Happiness

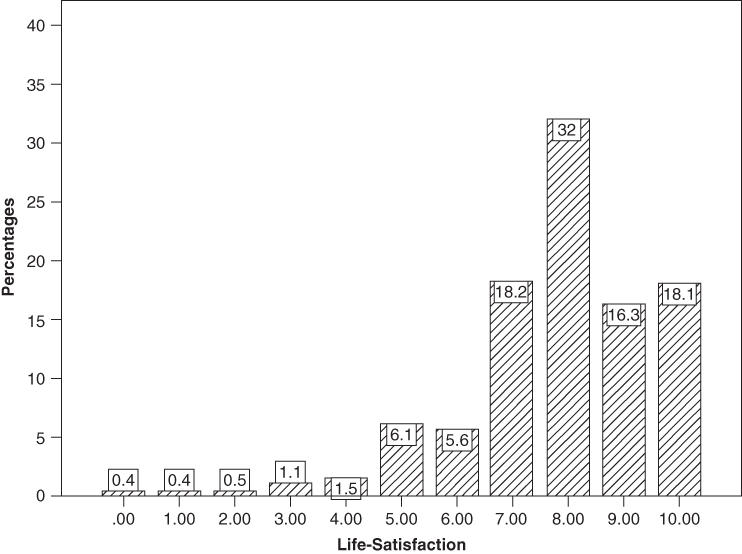

Average happiness in nations is not static, but has changed over the years, typically to the positive (see Figure 42.3). Particularly noteworthy is that average happiness has gone up in Denmark, where the level of happiness was already highest.

Figure 42.3 Trend average happiness in four nations.

Source: Happiness in Nations. World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013c).

In sum, enduring happiness for a great number of people is possible.

Can Happiness Be Manufactured?

The observation that people can be happy does mean that they can be made happier by public policy. Like the wind, happiness could be a natural phenomenon beyond our control. Several arguments have been raised in support of this view. A common reasoning holds that happiness is too complex a thing to be controlled. In this line, it is argued that conditions for happiness differ across cultures, and the dynamics of happiness are of a chaotic nature and one that will probably never be sufficiently understood. The claim that happiness cannot be created is also argued with a reversed reasoning. We understand happiness sufficiently well to realize that it cannot be raised. One argument is that happiness depends on comparison and that any improvement is, therefore, nullified by “reference drift” (VanPraag, 1993). Another claim in this context is that happiness is a trait-like matter and hence not sensitive to improvement in living conditions (Cummins, 2010). All this boils down to the conclusion that planned control of happiness is an illusion.

Can We Know Conditions for Happiness?

As in the case of health, conditions for happiness can be charted inductively using epidemiological research. Many such studies have been performed over the last decade. The results are documented in the earlier mentioned World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013a) and summarized in reviews by Argyle (2002); Diener, Suh, Lucas, and Smith (1999); and Veenhoven (1984, in press). What does this research teach us about conditions for happiness?

External Conditions

Happiness research has focused very much on social conditions for happiness. These conditions are studied at two levels: At the macro level, there are studies about the kind of society where people have the most happy lives, and at the micro level, there is much research about differences in happiness across social positions in society. As yet there is little research at the meso level. Little is known about the relation between happiness and labor organizations, for example.

Livability of Society

In Table 42.3, we have seen that average happiness differs greatly across nations. Table 42.4 shows that there is system in these differences. People live happier in rich nations than in poor ones, and happiness is also higher in nations characterized by rule of law, freedom, good citizenship, cultural plurality, and modernity. Not everything deemed desirable is related, however. Income equality in nations appears to be unrelated to average happiness.9

Table 42.4 Happiness and Society in 151 Nations in 2006

| Correlation with Happiness | |||

| Characteristics of Society | Zero Order | Controlled for Wealth | N |

| Affluence | +.61 | 136 | |

| Rule of Law | |||

|

+.49 | +.27 | 127 |

|

+.60 | +.24 | 145 |

|

+.15 | + .44 | 103 |

| Freedom | |||

|

+.54 | +.27 | 137 |

|

+.59 | +.36 | 131 |

|

+.46 | +.12 | 82 |

| Equality | |||

|

+.10 | –.21 | 119 |

|

+.78 | +.61 | 96 |

| Citizenship | |||

|

+.17 | +.15 | 145 |

|

+.61 | +.47 | 49 |

| Pluriformity | |||

|

+.27 | –.17 | 123 |

|

+.50 | +.35 | 81 |

| Modernity | |||

|

+.52 | +.24 | 145 |

|

+.61 | +.27 | 139 |

|

+.59 | +.32 | 136 |

| Explained variance (R2) | 84% | ||

Variables used: Happiness: HappinessLS10.11_2000s; Affluence: RGDP_2007; Civil rights: CivilLiberties_2004; Absence of corruption: Corruption3_2006; Murder rate: MurderRate_2004.09; Economic freedom: FreeEconIndex2_2007; Political freedom: DemocracyIndex5_2006; Personal freedom: PrivateFreedom_1990s; Income equality: IncomeInequality1_2005; Gender equality: GenderEqualIndex4_2007; Participation in voluntary associations: VolunteerActive2_2010; Preference for participative leadership: GoodLeaderParticip_1990s; % migrants: EthnicDiversity2_1955.2001; Tolerance towards minorities: Tolerance_1990s2; Schooling: EduEnrolGrossRatio_2000_04; Informatization: InternetUse_2005; Urbanization: UrbanPopulation_2005.

Source: States of Nations. World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013e).

There is much interrelation between the societal characteristics in Table 42.4; the most affluent nations are also the most free and modern ones. It is therefore difficult to estimate the effect of each of these variables separately. Still, it is evident that these variables together explain almost all the differences in happiness across nations; R2 is .84!

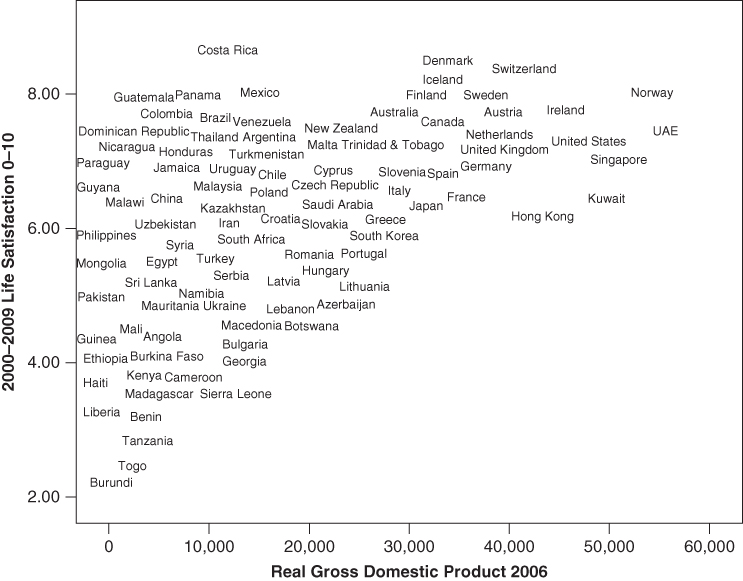

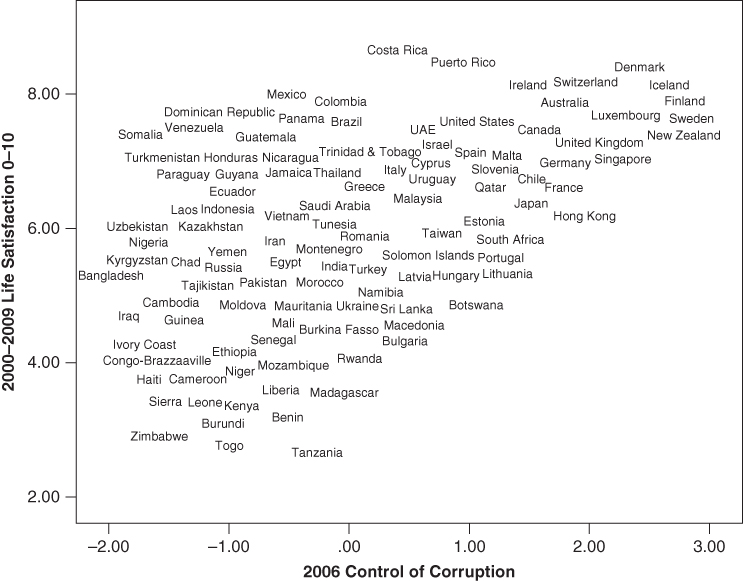

The relationship between happiness and material affluence is presented in more detail in Figure 42.4. Note that the relationship is not linear, but tends to a convex pattern. This indicates that economic affluence is subject to the economic law of diminishing returns, which means that economic growth will add less to average happiness in poor nations than in rich countries.10 This pattern of diminishing returns is not general. Figure 42.5 shows that the relationship with corruption is more linear, which suggests that happiness can be improved by combating corruption—even in the least corrupt countries.

Figure 42.4 Affluence and happiness in 123 nations in 2006.

Source: States of Nations. World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013e). Variables: HappinessLS10.11_2000s and RGDP_2007

Figure 42.5 Absence of corruption and happiness in 125 nations in 2006.

Source: States of Nations. World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013e). Variables: HappinessLS10.11_2000s and Corruption3_2006

These findings fit the theory that happiness depends very much on the degree to which living conditions fit universal human needs (livability theory). They do not fit the theory that happiness depends on culturally variable wants (comparison theory) or that happiness is geared by culturally specific ideas about life (folklore theory). I have discussed these theoretical implications in more detail elsewhere (Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, 1995).

Position in Society

Many studies have considered the relationship between happiness and position in society. The main results are summarized in Table 42.5. Happiness is moderately related to social rank in Western nations, and in non-Western nations, the correlations tend to be stronger. Happiness is also related to social participation, and this relationship seems to be universal. Being embedded in primary networks appears to be crucial to happiness, in particular, being married. This relationship is also universal. Surprisingly, the presence of offspring is unrelated to happiness, at least in present-day Western nations.

Table 42.5 Happiness and Position in Society

| Correlation within Western nationsa | Similarity of correlation across all nationsb | |

| Social rank | ||

| Income | + | – |

| Education | ± | – |

| Occupational prestige | + | + |

| Social participation | ||

| Employment | ± | + |

| Participation in associations | + | + |

| Primary network | ||

| Spouse | ++ | + |

| Children | 0 | ? |

| Friends | + | + |

a++ = Strong positive; + = Positive; 0 = No relationship; – = Negative; ? = Not yet investigated; ± = varying

b+ = Similar; – = Different; ? = No data

Source: Correlational Findings. World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013b).

These illustrative findings suggest that happiness can be improved by facilitating social participation and primary networks (see Myers, Chapter 41, this volume).

Internal Conditions

Happiness depends on the livability of the environment, and on the individual's ability to deal with that environment. What abilities are most crucial? Some findings are presented in Table 6. Research findings show that good health is an important requirement and that mental health is more critical to happiness than physical health. This pattern of correlations is universal. Intelligence appears to be unrelated to happiness, at least school intelligence as measured by common IQ tests.11 Happiness is strongly linked to psychological autonomy in Western nations. This appears in correlations with inner control, independence, and assertiveness. We lack data on this matter from non-Western nations.

Table 6 Happiness and Life-Abilities

| Correlation | Similarity of correlation | |

| within Western nationsa | across all nationsb | |

| Proficiencies | ||

| Physical health | + | + |

| Mental health | ++ | + |

| IQ | 0 | + |

| Personality | ||

| Internal control | + | + |

| Extraversion | + | + |

| Conscientiousness | + | ? |

| Art of living | ||

| Lust acceptance | + | + |

| Sociability | ++ | + |

a++ = Strong positive; + = Positive; 0 = No relationship; – = Negative; ? = Not yet investigated; ± = Varying;

b+ = Similar; – = Different; ? = No data

Source: Correlational Findings. World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2013b).

Happiness has also been found to be related to moral conviction. The happy are more acceptant of pleasure than the unhappy, and they are more likely to endorse social values such as solidarity, tolerance, and love. Conversely, the happy tend to be less materialistic than the unhappy. It is as yet unclear whether this pattern is universal.

From an evolutionary view, it is also unlikely that happiness is a trait-like matter. If so, happiness could not be functional and neither could the affective signals on which it draws. It is more plausible that happiness is part of our adaptive equipment and that it serves as a compass in life. Mobile organisms must be able to decide whether they are in the right pond or not, and hedonic experience is a main strand of information when determining the answer. If the animal is in a biotope that does not fit its abilities, it will feel bad and move away. This seasoned orientation system still exists in humans, who, moreover, can estimate how well they feel over longer periods and reflect on the possible reasons for their feeling. In this view, happiness is an automatic signal that indicates an organism or person's thriving. In addition, it is logical that we can raise happiness by facilitating conditions in which people thrive.

In sum, happiness of the great number can be raised, just like public health can be promoted. At best, there is an upper limit to happiness, analogous to the ceiling of longevity.

Is Happiness a Desirable Outcome?

The fact that public happiness can be raised does not mean that happiness should be raised. Several arguments have been brought against this idea. Happiness has been denounced as trivial and of less worth than other goal values. It has also been argued that happiness will spoil people and that the promotion of happiness requires objectionable means. Much of this criticism has been advanced in discussions about different concepts of happiness. The question here is whether these objections apply for happiness as life-satisfaction.

Is Happiness Really Desirable?

In his Brave New World, Huxley (1932) paints a tarnished picture of mass happiness. In this imaginary model society, citizens derive their happiness from uninformed unconcern and from sensory indulgence in sex and a drug called soma. This is indeed superficial enjoyment, but is this enjoyment happiness? It is not. This kind of experience was classified as pleasures on the top left in Table 2 and distinguished from life-satisfaction in the bottom right. Enduring satisfaction with life-as-a-whole cannot be achieved by mere passive consumption. Research shows that it is typically a byproduct of active involvement. Likewise, Adorno depicted happiness as a temporary escape from reality and rejected it for that reason (Rath, 2002). Here, happiness is mixed up with top-experience. Life-satisfaction is typically not escapism. Research shows that it is linked with reality control.

Happiness has also been equated with social success and, on that basis, rejected as conformist rat-race behavior. This criticism may apply to satisfaction in the domain of career (top right quadrant in Table 2), but not to satisfaction with life-as-a-whole (bottom right quadrant). In fact, happy people tend to be independent rather than conformist and tend not to be materialistic. Happiness has also been denounced on the basis of assumptions about its determinants. As noted earlier, it is commonly assumed that happiness depends on social comparison. In this view, happiness is merely thinking oneself to be better off than the Joneses. Likewise, it is assumed that happiness depends on the meeting of culturally determined standards of success, and that the happiness of present-day Americans draws on their ability to live up to the models presented in advertisements. Both these theories see happiness as cognitive contentment and miss the point that happiness is essentially an affective phenomenon that signals how well we thrive (Veenhoven, 2009).

In sum, there are no good reasons to denounce happiness as insignificant.

Is Happiness the Most Desirable Value?

Agreeing that happiness is desirable is one thing, but the tenet of utilitarianism is that happiness is the most desirable value. This claim is criticized on two grounds: First, it is objected that it does not make sense to premise one particular value, and second, there are values that rank higher than happiness. There is a longstanding philosophical discussion on these issues (Sen & Williams, 1982; Smart & Williams 1973), to which the newly gained knowledge about happiness can add the following points.

One new argument in this discussion is in the previously mentioned signal function of happiness. If happiness does indeed reflect how well we thrive, it concurs with living according to our nature. From a humanistic perspective, this is valuable.

Another novelty is in the insight that effect of external living conditions on happiness depends on inner life-abilities (Table 2). Democracy is generally deemed to be good, but it does not work well with anxious and uneducated voters. Likewise, conformism is generally deemed to be bad, but it can be functional in collectivist conditions. This helps us to understand that general end values cannot be found in the top quadrants. Instead, end values are to be found in the bottom quadrants, in particular, the bottom right quadrant. Happiness and longevity indicate how well a person's life-abilities fit the conditions in which that person lives, and as such, reflect more value than is found in each of the top quadrants separately. Happiness is a more inclusive merit than most other values, since it reflects an optimal combination.

A related point is that there are limits to most values, too much freedom leads into anarchy, and too much equality leads into apathy. The problem is that we do not know where the optimum level lies and how optima vary in different value combinations. Here again, happiness is a useful indicator. If most people live long and happily, the mix is apparently livable. In sum, if one opts for one particular end value, happiness is a good candidate.

Will Promotion of Happiness Take Place at the Cost of Other Values?

Even if there is nothing wrong with happiness in itself, maximization of it could still work out negatively for other valued matters. Critics of utilitarianism claim this will happen. They foresee that greater happiness will make people less caring and responsible and fear that the premise for happiness will legitimize amoral means. This state of affairs is also described in Brave New World, where citizens are concerned only with petty pleasures and the government is dictatorial.

Does Happiness Spoil?

Over the ages, preachers of penitence have glorified suffering. This sermonizing lives on in the idea that happiness does not bring out the best of us. Happiness is said to nurture self-sufficient attitudes and to make people less sensitive to the suffering of their fellows. Happiness is also seen to lead to complacency and thereby to demean initiative and creativeness. It is also said that happiness fosters superficial hedonism and that these negative effects on individuals will harm society in the long run. Hence, promotion of happiness is seen to lead into societal decay—Nero playing happily in a decadent Rome that is burning around him.

There is some literature on the positive effects of happiness, recently in the context of positive psychology. This writing suggests that happiness is an activating force and facilitates involvement in tasks and people. Happiness is seen to open us to the world, while unhappiness invites us to retreat (Fredrickson, 2000). This view fits the theory that happiness functions as a “go” signal. Research findings support this latter view of the consequences of happiness. Happiness is strongly correlated with activity and predicts sociable behaviors, such as helping. Happiness also has a positive effect on intimate relations. There is also good evidence that happiness lengthens life (Danner, Snowdon, & Friessen, 2001). Thus, happiness is clearly good for us. All this does not deny that happiness may involve some negative effects, but apparently the positive effects dominate.

Does a Premise for Happiness Excuse Amoral Means?

The main objection against utilitarianism is that the greatest happiness principle justifies any way to improve happiness and hence permits morally rejectable ways, such as genetic manipulation, mind control, and political repression. It is also felt that the rights of minorities will be sacrificed on the altar of the greatest number.

The possibility of such undesirable consequences is indeed implied in the logic of radical utilitarianism, but is it likely to materialize? The available data suggest this is not true. In Table 4 we have seen that citizens are happiest in nations that respect human rights and allow freedom. It also appears that people are happiest in the most educated and informatized nations. Likewise, happy people tend to be active and independent. In fact, there is no empirical evidence for any real value conflict. The problem exists in theory, but not in reality.

In sum, there is no ground for the fear that maximizing of happiness will lead into consequences that are morally rejectable.

Conclusion

The empirical tests falsify all the theoretical objections against the greatest happiness principle. The criterion appears practically feasible and morally sound. Hence the greatest happiness principle deserves a more prominent place in policy making.

Summary Points

- Happiness can be defined as subjective enjoyment of one's life as a whole.

- This happiness of great numbers of people can be measured using surveys.

- Conditions for happiness can be identified inductively.

- Effects of policies on happiness can be assessed empirically.

- Hence, evidence-based happiness policy is possible.

- Happiness is a desirable policy goal in itself.

- The pursuit of greater happiness for a greater number does not interfere with other values.

References

- Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: Americans' perceptions of life quality. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Argyle, M. (2002). The psychology of happiness (3rd ed., rev.). London, England: Methuen.

- Bentham, J. (1789). Introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. London, England: Payne.

- Berg, M., & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. In B. Greve (Ed.), Social policy and happiness in Europe (pp. 174–194). Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

- Bradburn, N. M., & Caplovitz, D. (1965). Reports on happiness: A pilot study of behavior related to mental health. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation level theory: A symposium (pp. 287–302). London, England: Academic Press.

- Campbell, A. (1981). The sense of well-being in America. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concern. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Cummins, R. A. (2010). Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: A synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 1–17.

- Danner, D. D., Snowdon, D. A., & Friessen, W. V. (2001). Positive emotions in early life and longevity: Findings from the nun-study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 804–819.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–301.

- Ehrhardt, J. J., Saris, W. E., & Veenhoven, R. (2000). Stability of life-satisfaction over time: Analysis of ranks in a national population. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 177–205.

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, P. W. (1975). Unmasking the face. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevention and Treatment, 3, article 1a.

- Freud, S. (1948). Das Unbehagen mit der Kultur, Gesammte Werke aus den Jahren 1925–1931 [Culture and its discontents]. Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany: Fisher Verlag. (Original work published 1929)

- Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics: How the economy and institutions affect human well-being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gallup World Poll. (2007). Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/strategicconsulting/en-us/worldpoll.aspx

- Gerson, E. M. (1976). On quality of life. American Sociological Review, 41, 793–806.

- Gurin, G., Veroff, J., & Feld, S. (1960). Americans view their mental health. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Huxley, A. (1932). Brave new world. Stockholm, Sweden: Continental Books.

- Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Lane, R. E. (2000). The loss of happiness in market democracies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Neugarten, B. L., Havighurst, R. J., & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16, 134–143.

- Rath, N. (2002). The concept of happiness in Adorno's critical theory. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 1–21.

- Schimmack, U., & Diener, E. (Eds.). (2003). Experience sampling methodology in happiness research [Special Issue]. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–4.

- Sen, A. (1993). Capability and wellbeing. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 30–53). Oxford, England: Clarendon.

- Sen, A., & Williams, B. (Eds.). (1982). Utilitarianism and beyond. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Smart, J. J., & Williams, B. (1973). Utilitarianism, for and against. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- VanPraag, B. M. (1993). The relativity of welfare. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 362–385). Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

- Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24, 1–34.

- Veenhoven, R. (1993). Happiness in nations: Subjective appreciation of life in 56 nations 1946–1992. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Erasmus University Press, Center for Socio-Cultural Transformation, RISBO.

- Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life: Ordering concepts and measures of the good life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 1–39.

- Veenhoven, R. (2009). How do we assess how happy we are? In A. K. Dutt & B. Radcliff (Eds.), Happiness, economics and politics: Towards a multi-disciplinary approach (pp. 45–69). Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar.

- Veenhoven, R. (2013a). Archive of research findings on subjective enjoyment of life. World Database of Happiness. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Erasmus University Press. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl

- Veenhoven, R. (2013b). Correlational findings. World Database of Happiness. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_cor/cor_fp.htm

- Veenhoven, R. (2013c). Happiness in nations. World Database of Happiness. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_nat/nat_fp.php

- Veenhoven, R. (2013d). Measures of happiness. World Database of Happiness. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_quer/hqi_fp.htm

- Veenhoven, R. (2013e). States of nations: Data set for the cross-national analysis of happiness. World Database of Happiness. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl//statnat/statnat_fp.htm

- Veenhoven, R. (in press). Overall satisfaction with life. In W. Glatzer (Ed.), Global handbook of quality of life. New York, NY: Springer.

- Veenhoven, R., & Choi, Y. (2012). Does intelligence boost happiness? Smartness of all pays more than being smarter. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1, 5–27.

- Veenhoven, R., & Ehrhardt, J. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 43, 33–86.

- Veenhoven, R., & Vergunst, F. (in press). The Easterlin illusion: Economic growth does go with greater happiness. International Journal of Happiness and Development.

- Ware, J. E., Jr. (1996). The SF-36 Health Survey. In B. Spilker (Ed.), Quality of life and pharmaco-economics in clinical trials (pp. 337–345). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven.

- Wessman, A. E., & Ricks, D. F. (1966). Mood and personality. New York, NY: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston.