6. How and Why They Spin: Inside Key Wheels

“God made man to go by motives, and he will not go without them, any more than a boat without steam or a balloon without gas.”

—Henry Ward Beecher

While there are millions of gears in America’s healthcare machine, four types stand out as being the most important politically and economically. Indeed, from the perspective of the cost and efficiency of healthcare, no other wheels even come close. These four entities are doctors and other healthcare providers, health insurers, government, and patients.

The contents of this chapter help explain why the entire machine behaves in what might seem to be an illogical and irrational fashion. It is often difficult for the average person to understand why different components of the healthcare system might be at odds. After all, we are taught from an early age that doctors are here to cure us, insurance companies are created to protect us, and the government is supposed to look after its citizens. How then is it possible for some or all of these missions to be at odds? The answer lies in the fact that the business model behind an economic entity can sometimes require it to take actions that would otherwise be contrary to its mission statement.

Doctors and Other Healthcare Providers*

* We will be using “healthcare providers” as a general term to represent all people within the healthcare system whose primary function is to care for patients. In practice, healthcare providers are numerous and diverse, ranging from highly specialized surgeons to home health providers. From a system perspective, the most important healthcare providers are those whose job requires them to make decisions about resource use. Physicians are the most important providers in this regard.

Doctors are the most important medical component of any healthcare system. There are about 820,000 active physicians in the United States. About one-third of these are generalists and two-thirds are specialists.† Collectively they influence about 80% of all healthcare spending. Relatively little of that money goes to them, however. In aggregate, physician and clinical services only account for 21% of all healthcare expenditures, or $448 billion in 2006.1 Instead, physicians account for the vast majority of healthcare spending via the decisions they make and transactions they initiate. Those decisions and transactions account for most everything we experience as patients—from what tests will be ordered, to surgeries or therapies to be performed, whether and what hospitals will be used, which other providers will see patients, what drugs will be used, and how often we’ll return for visits. The long, expensive and often arduous education and training that doctors go through makes them better qualified than anyone else to know whether and which transactions should be performed on behalf of a given patient. This does not mean that patients, families, insurers, administrators, or governments necessarily listen to physicians or do what doctors recommend. The situation is far more complex than that. Nevertheless, physicians as a group are terribly important to any healthcare analysis, and they generally behave in rational and predictable ways.

† “Generalists” are usually considered to be physicians practicing family practice, general medicine, and general pediatrics. Everyone else is considered to be a specialist.

As we saw in Figure 3.11, most doctors in the United States make more money than the average person, but generally less than or equal to the money made by the CEO of a small business.‡ Whether U.S. physicians deserve all the money they make is a common question. On one hand, the salary of the prototypical general practitioner is 3.4 times the median household income, and that of the average specialist is 4.8 times higher. On the other hand, training a physician requires a substantial amount of time, money, and dedication—including an undergraduate degree, four years of medical school, and then an additional three to seven years of internship and residency training. The average U.S. physician will be nearly thirty years old before entering the workforce as a fully qualified practitioner. By that time, 86.7% of them will have outstanding educational loans, with an average debt of $129,943.

‡ According to Salary.com’s 2007 Annual Small Business Executive Compensation Survey, the national median salary for a small-business CEO is $233,500. For a company with 500 to 5,000 employees, the average CEO salary is $500,000. For companies with more than 5,000 employees, the number increased to $849,375.

The combination of a shorter-than-average working life, higher-than-average educational debt, long training times, and declining job satisfaction suggest that high salaries are needed to train and keep good providers around. However, real physician income in the United States has been declining steadily since 1995.2 From 2004 to 2006 alone, physicians’ real income after inflation fell an average of 7.1%, despite seeing more patients.3 This inflation-adjusted decline is in contrast to dramatic increases in both medical inflation and smaller increases in the wages of nonmedical professionals. Physician income is clearly not the cause of escalating healthcare costs in the United States.

Regardless of salary levels, there is a relative shortage of physicians in the United States; a shortage that is guaranteed to get much worse as a result of the PPACA. One reason for the shortage is that all this training is relatively scarce and expensive. Estimates are that it costs about $250,000 to train a medical student, and then at least $110,000 per year to train a resident physician. This cost, plus the fact that the number of training positions is regulated by government and academia rather than market forces, means that the United States has fewer physicians per capita than the majority of economically developed countries: only 2.4 per 1,000 population, compared to an OECD average of 3.0 per 1,000 population. From 1980 to 2000, the yearly number of American medical school graduates remained unchanged at about 16,000, while the population as a whole increased by 71 million. As is the case with much of the U.S. economy, imports—in this case, of doctors—made up much of the difference. In 2005, “international medical graduates” (that is, foreign-trained doctors) made up 25.3% of practicing physicians in the United States.

The shortage is particularly severe—and getting worse each year—with respect to primary care physicians. These include family practitioners, internal medicine physicians, general pediatricians, and obstetricians, who serve as the primary care providers for pregnant women. Although the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that the supply of primary care physicians actually grew at a rate of about 1% per year between 1995 and 2006, this figure is deceptive.4 The GAO counted the total number of providers training in specific residency programs required for primary care—internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics—but did not take the additional step of determining whether these providers actually intended to enter general practice. In fact, the number of U.S. medical school graduates going into family practice declined by more than half from 1997 to 2005. In 2006, only 13% of first-year internal medicine residents said that they intended to pursue general practice.5

While the shortage of primary care physicians in the United States might seem like a minor problem now, it will become increasingly serious over the next ten years. When Massachusetts adopted its own law making healthcare coverage universal (the law that the 2010 “Obamacare” law is based upon), the average wait for a primary care appointment rose from 33 to 52 days almost immediately.6 Only half of the general internists were taking new patients at all. Practices closed to new patients are already becoming more common nationwide, especially for those with poor insurance coverage. In 2008, 45% of providers in Oregon had closed their practices to new Medicare patients.7 In the long term, the trend will be made substantially worse by the aging of the U.S. population. The American College of Physicians estimates that 40% more primary care physicians will be needed as a result of the aging population by 2020.

So we know that doctors are relatively scarce, hard and expensive to train, and are an essential key to most of the healthcare transactions that occur each day. Losing or discouraging them would probably be a bad thing. What do we know about they way they think and behave economically?

Physician Economics and Motivation

About half of the physicians in this country are small businessmen. Based upon surveys by the American Medical Association, the majority of medical practices in the United States are small—employing 10 or fewer physicians. The remaining clinicians work for larger clinics and institutions such as Kaiser Permanente, the Veterans Administration (VA), the military, medical schools and hospitals, and group practices. Collectively, small practices account for about 50% of all clinically active physicians nationwide, but have a disproportionately large impact on healthcare as a whole. That’s because small and independent practices handle the majority of private-pay patients in all parts of the country. In doing so, they have far more discretion with respect to what drugs will be used, what labs will be tapped and which additional resources will be devoted to any given case than their institutional counterparts in the military, VA, or health maintenance organizations (HMOs) such as Kaiser.

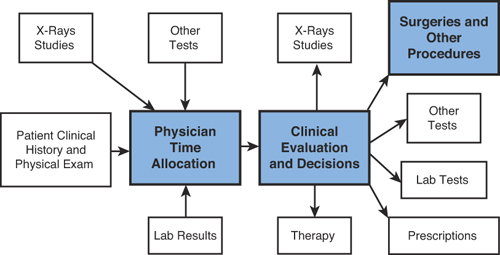

Because they are businessmen, physicians react to financial incentives and disincentives in a rational way based upon how they affect net income. Probably the easiest way to think of a medical practice is as a small factory or production line, with clinical data as the raw input, the physician’s time used as the processing tool, and clinical decisions leading to additional healthcare transactions as the output. In Figure 6.1, the things that doctors do are shown by the boxes labeled with bold type.

Figure 6.1. Production Process in a Medical Practice

As you can see, doctors basically use their time to gather and process information from a wide variety of sources, and produce two billable types of output: (1) a clinical evaluation in which decisions dictate further actions; and/or (2) surgeries or other procedures that may or may not be done on the same visit. The only useful inventory any physician has is his or her time, exactly like attorneys, accountants, and business consultants of all types. However, unlike other professionals, doctors are not paid for their time on an hourly basis. Instead, they’re paid quite differently, according to a concept called “procedures.”

Procedures were invented as a way of bundling most or all the tasks associated with an episode of care into one flat fee. This structure is particularly convenient for two groups. The first is insurers, who can predetermine what any particular type of visit will cost them simply by fixing the price they’ll pay. This method allows both the individual and cumulative cost of nearly all surgeries or other invasive procedures to be predicted with some reliability. Paying for procedures also allows insurance companies to offload the risk of many procedures onto doctors by a process called “bundling.” A simple example of bundling is for an insurance company to say that it will pay a single fee for a specific surgery and all follow-up care associated with that procedure. If the patient develops a complication as a result of the surgery and must be seen multiple times, bundling forces the doctor to see the patient and manage those complications on his own dime. Because all surgeries are associated with a known risk of complication, this strategy allows the insurer to transfer the risk of caring for the complication to the provider.

The second group is a subset of doctors, including surgeons and radiologists, who perform procedures that are only loosely related to time. These specialists can, under certain circumstances, work quickly and churn out many procedures per day. This “crank-’em-out” option is not available to primary care doctors or those in the so-called “cognitive” specialties. These doctors must spend a substantial amount of time actually interacting with patients as a part of what they do. For these physicians, the value of a “procedure” is based mostly upon the time spent with the patient and the perceived complexity of the medical problem. A given doctor can see fewer sicker patients or more healthier patients and receive roughly the same compensation.

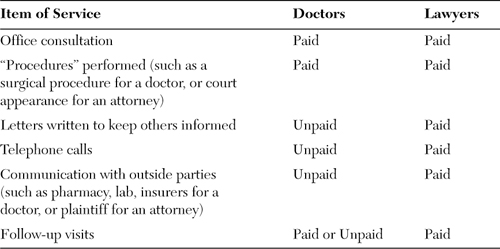

Although it might seem as if valuing office visits of different lengths as procedures is equivalent to providing doctors with an hourly rate, there are some key differences in how doctors are paid when compared to other professionals. As you can see in Table 6.1, the financial anatomy of a doctor’s visit is quite different from that of, for example, a visit to an attorney. Whereas attorneys and other professionals are paid for each and every use of their time, physicians are paid only for certain uses of their time.

Table 6.1. Comparison of Payment for Various Activities Performed by Physicians and Attorneys

Thus while time is money for everyone, a substantial portion of the time that doctors spend in the office is essentially uncompensated. The impact of these differences is actually quite important in the scheme of healthcare delivery, and its effects can be seen every day in the operation of clinics, as piles of prescriptions, lab requisitions, and referrals are processed.

Clearly the most sensitive and economically destructive use of physician time is performing administrative tasks that have little or nothing to do with actual patient care. Not only are physicians small business owners, but their personal time and skills are the only source of income for their business, and the only source of care for their customers—patients. Any unnecessary administrative burden on clinicians costs them money and deprives society of a scarce resource. As we’ll see, this is a major source of healthcare cost inefficiency.

Health Insurers

There are two major sources of health insurance in the United States: private health insurance companies, and government agencies, such as Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance has been the basis of U.S. healthcare coverage for the past 90 years, with the federal government only entering the picture in the 1960s. As a result, the vast majority of Americans are covered through private insurance. About 171 million Americans had private healthcare coverage in 2006, with about 158 million of them obtaining insurance through their workplace. This compares with 43 million Medicare enrollees, 36 million covered by Medicaid, and 44 million Americans with no insurance coverage at all in that year.8

Private health insurers hold sway over the lives of patients, providers, and payers as a result of the sheer numbers that they insure. Medicare and Medicaid exercise enormous influence because their policies are backed by the force and power of the federal government.

Private and public insurers differ considerably with respect to how they work as businesses. We’ll look at their business structure first, and then compare their similarities and differences as actors on the healthcare stage.

Private Insurers

Private insurers are either for-profit companies such as Aetna and Metropolitan Life, or nonprofit entities such as some of the Blue Cross/Blue Shield organizations. For all practical purposes, there is little or no difference between the two. For-profit and nonprofit insurers operate under the same business conditions and behave in exactly the same way with respect to their customers, patients, and providers. In the case of health insurance, being “nonprofit” is strictly a tax status rather than a business plan.

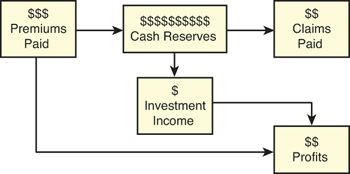

In theory, the business of private insurance is fairly simple. Like casinos, insurers basically engage in a legalized form of gambling. Insurers take the other side of a bet that their customer wishes to place. In the case of health insurance, insurance companies are willing to bet that: (1) a whole group of policyholders won’t all get sick at the same time; and (2) that the regular bets placed by their customers (in the form of premium payments) will more than cover whatever payouts do have to be made when illnesses do occur. Like “the house” in a casino, each insurance company has to weight the odds in its own favor if this mechanism is to work and a profit is to be made. And like casinos, health insurers make money in two ways. The first is by collecting “bets” (in this case, insurance premiums). The second is by investing the cash reserves that the companies must keep on hand in order to pay out when luck turns against the house. The business basis of any private insurer—including health insurers—is shown in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2. The Basic Insurance Business Model

There are several key elements that an insurance company can and must control if it’s going to make a profit. First, it can decide whose bet it will take, and whose it won’t. Just as known professional gamblers and card counters aren’t welcome in casinos because of the likelihood that they will cost the house money, people who are likely to receive more in medical benefits than they pay in premiums will be turned away by any insurance company allowed to do so. The selection of who an insurance company will and will not insure is a powerful tool wielded by the medical underwriting department of each insurer.

Second, an insurer can limit the amount that it pays out by adjusting the conditions under which it pays out its losses. This is similar to a casino adjusting both the amount and odds of the payout on a slot machine.

Third, both insurers and casinos can enhance or diminish their returns with the quality of their investment decisions. Whereas investment income is a secondary source of income for most businesses, it’s a major source of revenue for casinos, insurers, and other businesses that are required to keep large amounts of cash on hand at all times.

Of course, the comparison of an insurance company with a casino has its limitations. First, casinos have the benefit of knowing the exact mathematically determined odds for every bet they take. Dice, cards, roulette wheels, and slot machines don’t have the ability to influence their own outcomes, as people often do with their health. People can and do affect their own health in dozens of ways, from diet and exercise to taking (or not taking) medications and engaging in risky behavior. Second, living organisms show great variability in their susceptibility and response to illness. Even the best efforts to screen out high-risk individuals can be foiled by accidentally covering customers with a few bad genes. Third, there is the problem of “moral hazard,” in which relatively young and healthy people will avoid having to pay for healthcare insurance, while sicker individuals eagerly seek coverage. Fourth, new federal regulations will require insurance companies to write policies for anyone, no matter what their medical problems might be. This means that many people with potentially costly conditions will be entering the system. Finally, the cost of the bets insurers need to cover is affected by changes in the price of healthcare services themselves.

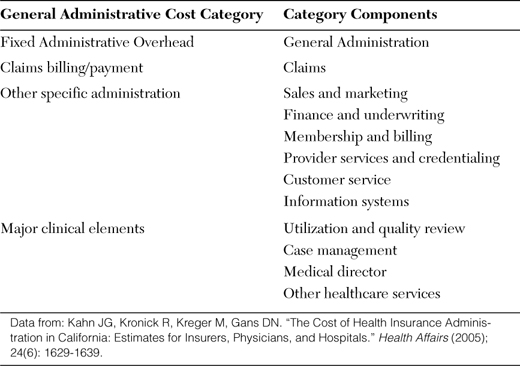

These differences between insurers and casinos account for a substantial difference in the way that casinos and insurers place their bets and spend their money. Although both casinos and insurers must spend money on sales and marketing, insurers must spend far more on people whose jobs are to set premium levels and minimize losses on lost bets. This is easily seen by looking at the administration cost categories of a typical commercial insurer in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2. Administration Cost Categories for Health Insurers9

Outflows of reserve dollars that are used to pay for healthcare goods and services are called “medical losses” in the industry, and the amount of money paid out in claims as a percentage of premiums is called the “medical loss ratio” (MLR). Medical loss ratios vary considerably from company to company and from year to year. In 2007, the medical loss ratios for a sample of 15 full-service health plans in California ranged from a low of 69.4% to a high of 95.3%, with an average of 84.7%.10 Money left over after paying for medical losses is used to pay for administration and company profits. It should be obvious that, from a shareholder perspective, private insurance companies should be obsessed with minimizing medical losses. Medical losses eat up profits, and the goal of every insurance employee hoping for a year-end bonus will be to reduce them at every opportunity.

The drive to reduce medical losses is the source of much of the resentment that average people feel toward the current healthcare system. It is also the source of much of the inefficiency that is now threatening to topple the system itself. From a business perspective, it’s important to realize that the structure, function, and behavior of private insurers are an inevitable result of the business model that we’ve just reviewed. Private insurance companies might want to provide healthcare coverage to everyone and work quickly and fairly with providers, but they can’t do so and still remain competitive with their less scrupulous counterparts. To understand this, we need to look at the tools and processes that private insurers have at their disposal to stay in business and earn a profit.

Private Insurance Economics and Motivation

Health insurance companies have four basic tools for increasing revenues and minimizing losses:

• Increase premiums, thereby increasing premium revenue

• Clever investment of reserve funds to increase investment revenue

• Prevent high-risk individuals from entering their insurance pool

• Minimize the benefits provided to patients

Each of these presents a challenge to company management and the healthcare system as a whole.

Premiums

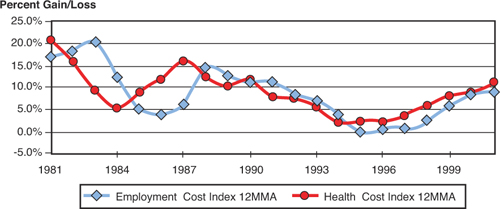

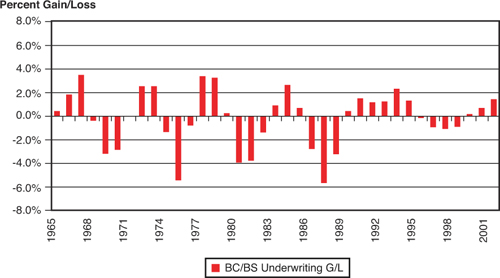

Setting prices would seem to be a relatively simple and straightforward way of ensuring adequate revenue for insurers. Unfortunately, it turns out to be very difficult to accurately predict what those premiums should be. The problem is that when premiums are fixed for the year to come, they are based upon cost information that is typically at least six months old. The result is an 18-month lag between increases and decreases in claims expenses and the time that those changes can be priced into premiums. This lag creates a regular and recurring imbalance between premiums and medical losses called the “health insurance underwriting cycle.” As shown in Figure 6.3, the health insurance underwriting cycle is characterized by a repeated pattern of several years of insurance company profitability followed by several years of losses.

From: Kipp R, Cookson JP, Mattie LL. “Health Insurance Underwriting Cycle Effect on Health Plan Premiums and Profitability.” Milliman USA Report, April 10, 2003.11

Figure 6.3. Blue Cross/Blue Shield Underwriting Gains and Losses from 1965 to 2001

The cause of the underwriting cycle is easy to understand with a good example. An excellent one is provided by Kipp, Cookson, and Mattie12, and the process can be summarized as follows:

- Health insurers have to set and publish their premium changes for each new year several months before those rates take effect. Because of the time lags involved with collecting and analyzing claims data, this means that the premium rates going into effect on January 1st will be based on data that is six months old. So if medical expenses had been rising at a rate of 5% per year, but doubled to 10% in the period from July to December of 2011, the premiums for 2012 would still increase by only 5%.

- By the time insurers get around to setting rates for 2013, they have already lost money for all of 2012 in addition to the money lost in the latter half of 2011. Based upon their recent claims experience, rates for 2013 will now be increased by the new base increase of 10%, plus an additional 8% or so to make up for the increases that should have been implemented in 2011 and 2012. This means that their new rate increase to employers and individuals for 2013 will be 18%, even though they are assuming that claims are rising at a 10% rate.

- If actual claims rates in the latter half of 2012 should rise again to 12%, the insurer is now even further behind in setting an adequate level of premiums. Eventually it will try to get ahead of the curve by raising premiums even higher than its estimates of the rate of increase in medical claims. Those paying the premiums will be horrified to see their premiums rising much faster than the perceived rate of medical inflation. They will not understand that their premiums were actually too low several years ago, and that insurers are making up for that shortfall.

- The same process will repeat itself in reverse if the rate of increase in medical claims should fall. Changes in premiums will again lag the changes occurring in medical claims by a period of several years. Premiums will be too high for a period of several years. The net result is a cycle in which insurers using time-lagged and imperfect information will tend to under- and over-charge when compared to the appropriate level of premiums.

The effect of this cycle on insurance premiums can be seen by comparing trends in the Health Cost Index with the Employment Cost Index for Health Insurance Premiums, as shown in Figure 6.4. As you can see, changes in premiums as measured by the Employment Cost Index consistently lag changes in the Health Cost by about 18 months.

From: Kipp R, Cookson JP, Lattie LL. “Health Insurance Underwriting Cycle Effect on Health Plan Premiums and Profitability.” Milliman USA Report, April 10, 2003.13

Figure 6.4. Health Cost Index Versus Employment Cost Index for Health Insurance Premiums

Because we already know that cycles are common in many types of business, why does the health insurance underwriting cycle matter with respect to controlling costs and improving the efficiency of the health care system? The problem caused by these gyrations is not any ill intent on the part of insurers, but that each cost recovery episode of the cycle places an enormous strain on every other part of the healthcare system. During each recovery period, insurers are forced to increase premiums at a rapid rate while doing everything possible to reduce exposure to risk and payouts for medical claims. The result is a general increase in friction throughout the healthcare machine. Purchasers of health insurance see sudden and rapid rate increases. Patients see higher co-pays and deductibles, more stringent screening by medical underwriting departments, and a general reduction of benefits. And providers encounter intense pressure to minimize treatment expense, more administrative hurdles, and delays in payment.

Because of the lag time between setting premiums and obtaining the cost data needed for accurate pricing, the existence of an underwriting business cycle is probably unavoidable. What is useful to consider is whether the amplitude of that cycle and the friction that it creates can be minimized. This will be one of the issues addressed when we look at solutions to the current mess.

Investment Income

It should be no surprise that insurance companies are susceptible to the same ups and downs with respect to investment as the rest of us. In good times, investment income can provide a cushion against increases in healthcare costs and help moderate the need for premium increases. On the flip side, in bad economic times, the loss of investment income will—other things being equal—cause an increase in premiums above and beyond what would normally be needed to account for medical losses alone. This is because of the need to maintain a steady level of both reserves and corporate profits. The enormous fall in asset value that occurred in 2008 and 2009 is only now being fully reflected in higher premiums. In a system that relies heavily upon businesses to pay for health insurance premiums, these increases will have an additional adverse effect on company profits, cash flow and employment, prolonging the recession.

Preventing High-Risk Individuals from Entering the Insurance Pool

One of the basic tools used by both casinos and health insurers to limit their downside risk is refusing to accept bets from people who are likely to cost them money. For private insurers, this is the job of the medical underwriting department. Prior to accepting any applicant who can be legally refused coverage, the medical underwriting department reviews the application information for evidence of pre-existing conditions, a family history of illness, or any other factor that might suggest a higher-than-average risk of future medical spending. It’s obvious that this behavior is just as rational for individual insurance companies as it is for individual casinos. The problem, of course, is that these are exactly the people who most need health insurance. To assist them in this effort, insurance companies have even asked physicians to help them ferret out patients who might otherwise slip through the screening process. In California, Blue Cross was recently taken to task for asking physicians to review the insurance applications of their patients and “immediately” report any discrepancies between their patient’s medical conditions and the information in their applications.14

What’s important for us to understand is that a noncustomer’s need for healthcare services is not the insurance company’s problem. The company’s duty is to win its bets, make money, and stay in business. Doing so requires that it avoids recruiting sick people whenever possible. It is also logical that customers who become ill be dropped from covered status as soon as possible. Doing so is the business equivalent of a casino asking a card counter to cash in her chips and leave the premises.15 It’s even possible for an insurer to claim the moral high ground as part of a program to exclude patients with medical conditions from its risk pool. Insurers can plausibly argue that it’s their responsibility to keep premiums as low as possible for its insured customers.

The tendency of commercial insurers to avoid patients with pre-existing conditions (or, better still, have them covered by a competitor) illustrates one of the major difficulties of a healthcare system based upon private insurers. From a business perspective, commercial insurance works best if one of two conditions exists. The first is if an insurance company is free to “cherry pick” its customers and drop the expensive ones. The second is if the population is universally required to have healthcare coverage and high-risk individuals are spread evenly among all private insurers. While premiums will inevitably be higher with mandated universal coverage, there is no other way to provide insurance for high-risk patients under a private insurance model.

Minimizing the Benefits Provided to Patients

Casinos have it easy compared to private insurers in their ability to refuse services to high-risk clients. Once a gambler starts to win, all any casino has to do is ask them to leave. State and federal regulations might require insurers to keep an expensive patient on the rolls for a variety of reasons, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act§ (PPACA) will make it virtually impossible to drop expensive patients or limit the liabilities that they incur.

§ This is the 2,409-page 2010 healthcare law popularly known as “Obamacare.”

On the other side of the coin, health insurers have far more flexibility than casinos in determining whether and how they will pay for a given episode of care. When a roulette wheel says that it will pay 35:1 on double zero, it’s difficult to modify the payout when the ball happens to drop in the wrong slot. In contrast, health insurers possess a wide range of tools to limit both downside risk and payouts. While some of these methods are open for all to see, in his excellent book Fixing American Healthcare, Dr. Richard Fogoros accurately describes many of these tools as a form of “covert rationing.”

Some of these corrective measures are directed at the patient, while others are directed specifically at the patient’s physician. Here are some examples:

• Raising deductibles and co-pays. One advantage that insurers have is that coverage contracts typically last only for a 12 month period. At the end of this period, premiums, deductibles and co-pays are all subject to change. In some cases, this might be adequate to induce a business or individual policyholder to switch insurers.

• Limiting access to physicians. Since the popularization of “managed care” as a concept in the 1990s, most insurance companies have made use of either health maintenance organizations (HMOs) or preferred provider organizations (PPOs). This allows insurers to limit access to care in two ways. First, limiting the pool of providers improves the chances of having patients wait for scheduled appointments. Because many conditions are self-limited (or fatal) and go away on their own, this reduces the chances of a patient requiring tests and medications. Second, tying a physician population to an insurance plan—either by paying salaries directly or by controlling the supply of patients—makes it far easier to minimize payments, as described later.

• Use of drug formularies. The vast majority of people purchasing health insurance coverage are completely unaware of what medications a particular insurance plan may choose to cover. Moreover, unlike many provisions of a health policy, an insurer can choose to change its formulary at any time. Limiting access to specific medications can greatly reduce the financial impact of developing a wide variety of diseases. Removing (or failing to add) expensive medications as choices that insurance will pay for can easily save hundreds or thousands of dollars per patient per month.**

** This is no exaggeration. Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and other debilitating and complex diseases of the immune system have relatively few effective drugs to choose from. Most of the newer (and more effective) agents are extremely expensive. Patients with MS on a common health plan in Portland, Oregon were recently notified that one very effective drug called Rebif (interferon beta-1a), would no longer be included in the approved formulary of drugs. Patients would have the choice of switching to drugs known to be less effective, or paying for the drug themselves. Rebif treatment currently costs more than $1,000 per month.

• Delaying payment for healthcare goods and services. Investment income is a function of three factors: the size of the reserve pool, the rate of return, and the duration of investment. Simply waiting to pay claims is a way of maximizing the latter. Delaying payment is such a tried and true business management tool for health insurers that 47 states have had to pass “prompt payment laws.” These laws limit the amount of time that insurers can delay payment on a so-called “clean claim”—a request for payment that is unambiguous and correct. Of course, laws are one thing, but enforcement is another. Texas has had to pass three separate prompt payment laws, yet payments from insurers to healthcare providers there and elsewhere still frequently stretch well beyond 45 days.†† In many states, healthcare laws are pre-empted by a federal law called the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). ERISA does not have any sort of prompt payment provision. In many of those cases, a majority of clean and accurate claims will routinely go unpaid after 90 days.16

†† Athenahealth’s PayerView website (http://athenapayerview.com/) regularly documents the performance (good and bad) of health insurance companies with respect to delayed payments, requests for medical documentation before payment, transparency in reasons for claims denial and other factors. In 2008, New York Medicaid had the worst record for delayed payments as measured by the number of “days in accounts receivable,” at 137.3 days. The median value for all insurers included in the measure was 35.41.

There are many other ways for the creative health insurer to get around prompt payment laws. One is to simply deny that a claim was received. It’s very likely that no action will be required for at least 90 days until an inquiry is made, whereupon the insurer can simply request that the claim be resubmitted. A second technique is to request more information about the claim, such as copies of the associated medical records. Simply making a request for more information stops the clock on prompt payment laws because the insurer is entitled to determine that they are “reasonably obligated” to pay for the services rendered and that no fraud is involved. A third technique is to reject an otherwise clean claim because of minor typographical errors. All these techniques are especially effective when the rejection comes at the end of a 45-day “prompt payment” window.

• Underpaying for healthcare goods and services. The amount that an insurer is obligated to pay on a given claim is specified in an elaborate contract that each insurer has with that provider for that particular service. Because there are thousands of insurers and a given provider might have to deal with dozens or even hundreds of them, each doctor’s billing office must deal with hundreds of different contracts. This provides an opportunity for insurers to shave the payments owed to providers, and there is a high probability that they won’t be caught because the vast majority of providers don’t have sophisticated billing or accounting systems.

• Simply denying claims. Another extremely effective technique for limiting losses is to simply deny payment for claims, often based upon an interpretation of payment rules or a technicality. Many denials can be based solely upon an insurance company’s own interpretation of what it owes. Most of these denials are now computer-automated. Insurers use literally millions of rules (some of which are common to all insurers, and others that might be completely unique to a given insurer or even a given insurance policy) to match diagnoses, procedures, dates, authorizations, and a host of other factors.‡‡17 Clearly no provider is capable of knowing, much less adhering, to each of these. This imbalance has spawned an entirely new industry: “claims denial management.”

‡‡ A Wall Street Journal article on the growth of the “claims denial” industry documents these organized efforts: “Over the past decade, most insurers have adopted code-auditing software from companies such as McKesson and Ingenix. These advanced systems include several million coding rules to guard against overcharging, and are routinely updated with new rules to which claims must adhere.” It goes on to describe cases in which properly filed claims were automatically rejected by the software anyway.

It should be obvious that the claims denial management industry has nothing whatever to do with providing care. Instead, it’s entirely devoted to looking at each claim to be submitted to insurers to make sure that it passes all the tests necessary to get paid. Because these efforts try to use computers and software to anticipate and correct rules that will result in denials, the entire effort has been correctly labeled as a sort of “arms race.” The Center for Information Technology Leadership has estimated the annual cost of this computerized tug-of-war to be about $20 billion per year.§§

§§ According to Athenahealth, the worst claims denier in 2008 was Health Choice of Arizona, with an overall medical claims denial rate of 37.82%. The median value for insurers examined by Athenahealth for the same period was 8.64%. In the same survey, Wellcare of Georgia scored worst in terms of “denial transparency,” a measure of how clear it is as to why a given claim was denied, and what would have to be done to fix it. Only 63.23% of Wellcare’s denials were well explained. The survey median across all insurers for this measure was 83.11%.

• Manipulating physician incentives. If you’re covered by private insurance, the odds are that you’ve never looked at the contract that dictates whether and when they’ll pay for healthcare services. Few Americans ever do. There is an excellent chance that your policy contains a “managed care” component, such as enrollment in a Preferred Provider Organization (PPO), health maintenance organization (HMO), or Point-of-Service Plan (POS). Under these programs, the insurer can and does judge whether any particular treatment or diagnostic test meets its criteria of “medical necessity.” Its ruling on this issue usually determines whether the given treatment or test takes place. By inserting themselves directly into the healthcare process, health insurers are in a position to limit the resources used for each case if they wish. In practice, they do so both overtly and covertly.

Overt rationing is common, straightforward, and easy to understand. A primary care physician requests a referral to a specialist for a problem she doesn’t feel competent to handle, and the insurer’s referral coordinator says no. A surgeon requests permission to perform a liver transplant, and it’s denied. An endocrinologist recommends a newer drug to help manage a case of diabetes, and the drug is not covered by the formulary. Patients and providers might not like the ruling, but at least they know where they stand and can act accordingly.

Covert rationing is a completely different animal—one that is little known or understood by the general public. Dr. Richard Fogoros has written an entire book and maintains a blog on the subject of covert rationing, and is a keen observer of the subject.18 In describing the role of insurers in covert rationing, we will summarize some of his findings and observations.

Covert rationing is basically a situation in which insurers (or others) do not specifically deny access to care themselves, but coerce physicians or other healthcare providers into doing it for them.*** This coercion can take the form of positive incentives or negative incentives:

*** Covert rationing is not limited to private insurance. In its roles as a financier and regulator of healthcare services, the federal government also has a major role in covert rationing.

Example #1: “Bonus” pools. If the amount spent on patient care is less than projected, insurers can offer to share the savings with doctors. This, of course, gives those physicians a direct financial incentive to discourage their patients from consuming medical resources—either by not telling them about specific tests or treatments, or not prescribing them. This type of program is often operated by HMOs (now re-labeled “Accountable Care Organizations” (ACOs) under the PPACA), who contract with networks of independent primary care providers. The contract states that a certain amount will be paid to the doctors for their services, but that a portion of this will be withheld and paid out at the end of the year to clinicians whose average medical expenditures were below targeted levels. The extra money serves as a positive incentive for physicians to limit the cost of care wherever possible.

There is no question that these types of programs are effective in influencing physician behavior and reducing spending. A survey of primary care physicians in California found that 57% felt pressure to limit the number of referrals, and 17% believed that this pressure compromised the quality of care.19 An economic study found that these programs seemed to reduce medical utilization expenditures by about five percent.20

Example #2: Doctors can be “capitated.” Under capitation, each doctor in the managed care plan is paid a fixed amount to take care of each patient in their practice. The less each patient is seen (and the fewer resources used on their behalf), the more each physician gets to keep. This is also a positive incentive to limit the amount of care delivered.

Example #3: Doctors can be given payment contracts that forbid them from telling patients about certain treatment options. Until the late 1990s, many prominent insurers placed something called “gag clauses” into provider contracts. A gag clause is language that prohibits physicians from relaying certain types of information to patients. The primary purpose of gag clauses was to prohibit doctors from telling patients about expensive treatment options and incentives that HMOs might provide to doctors for limiting care. Although gag clauses have since been banned from organizations working with Medicare and Medicaid patients and by many state laws, they are a profound example of a negative form of covert rationing.†††

††† Interestingly enough, despite the absence of gag clauses, physicians still seem to be self-censoring what they tell patients based upon the doctor’s perception of what the insurer will allow. A survey of 720 physicians found that 31% reported deciding “not to offer a useful service to a patient because of health plan coverage rules.” (Wynia MK, VanGeest JB, Cummins DS, Wilson IB. “Do Physicians Not Offer Useful Services Because Of Coverage Restrictions?” Health Affairs (2003); 22 (4): 190-197.)

Example #4. “Peer” pressure. A universal tool currently employed by insurers is to compare clinicians with “peer groups” with respect to various aspects of their practice patterns. Doctors periodically receive letters—or even personal visits from insurance company representatives—in which their medical resource utilization is compared with an insurer-defined “peer group.” For example, a physician will be told that, of the top ten medications she prescribes, only two are generic, compared to five generic choices for her “peers.” She might then be told that she performs several expensive diagnostic procedures at a rate that is higher than other clinicians. The implication, of course, is that she is overprescribing the medications and procedures in question and should change her practice patterns accordingly.‡‡‡

‡‡‡ “Peer-pressure” comparison tactics can be quite effective in changing physician behavior, but we need to understand that this does not necessarily translate into good medical practice. The problem, of course, is that such comparisons are made without controlling for a number of important factors. First, are the patient populations being treated truly comparable? Certain specialists are often referred the toughest cases, including those in which generic treatments might have already failed. Second, generic equivalents simply do not exist for many newer drugs, and are therefore not comparable. Third, it might well be the case that the peer group is itself behind the times or is not providing optimal treatment.

Example #5: Physician “report cards.” Publishing data on the “quality” of physician performance is usually thought of as a public service meant to protect the public. However, as Dr. Fogoros has observed, what might initially seem to be a public service can also be an effective way of discouraging physician intervention in particularly expensive high-risk cases.21 His observations are based upon a study that looked at performing procedures on patients who had had heart attacks so severe that they were suffering from cardiogenic shock—a condition in which the heart is so severely damaged that it is not capable of supplying all the blood required by the body.22

New York has a system of reporting that publicizes the mortality rate of patients under the care of cardiologists and cardiovascular surgeons. This reporting does not, however, adjust the respective mortality scores of these physicians based upon the complexity of the cases they choose to treat. As a result, if you look at the treatment of high-risk cases—the cases that are most likely to result in mortality—New York heart doctors are now far more reluctant to intervene than doctors elsewhere.

Although it is unlikely that the creation of the physician-associated mortality ratings was originally intended to reduce healthcare expenses, it should be obvious that “report cards” can have important unintended consequences on physician behavior.

Self-Insured Businesses

Many larger companies self-insure, basically pooling risk among their employees, saving money to be used as reserves against claims, and acting as their own insurance agents. These businesses often employ third-party benefits administrators (TPAs) to run their health insurance operations. These TPAs are often commercial insurers. Nationwide, about 50 million Americans are currently covered by self-insured health benefits.

Self-insured operations differ from those of commercial insurers in several ways:

• Self-insured plans do not need to make a profit from their insurance operations.

• Unlike commercial insurers, self-insured plans are governed by federal laws rather than a combination of often overlapping and even conflicting state and federal laws. One important consequence is that these plans do not need to comply with state-mandated benefits regulations, and can offer the same plan across multiple states. This can dramatically reduce both the cost of benefits and administration.

• The employer is the beneficiary of investment income, rather than a third-party insurance company.

• Self-insured employers are not subject to state health insurance premium taxes. These are typically 2–3% of premiums paid.

• Employers can contract with any providers, and offer the same health plan and benefits to all of its employees regardless of locality.

• To limit their own downside risk, many employers purchase “stop-loss” insurance from commercial insurers. Stop-loss insurance is purchased to protect the business from claims beyond a given limit, (such as. $25,000), for a single incident/occurrence, or a series of occurrences that exceed a defined annual limit.

The nature of self-insured health plans vary as much the businesses themselves, with all degrees of coverage represented. The absence of a profit motive and state regulation allows this type of program to be more cost-efficient and less expensive to provide than conventional commercial insurance. They also have a great deal of flexibility with respect to the selection of covered providers, list of benefits covered, and payment terms. Many self-insured programs historically limited the risk to employers by specifying a lifetime benefit maximum for participants, as well as benefit caps for specific expensive procedures and illnesses, such as those requiring transplants.

Public Insurers

Public insurers are government institutions that provide insurance benefits to designated subsets of the general population. The most important of these are Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare was established in 1965 to provide care to those over 65 years old. Coverage for those who are disabled and under the age of 65 was added in 1972. Medicaid was likewise created in 1965, with the original intention of providing health insurance coverage to welfare recipients. Since then the Medicaid program has grown to become the predominant long-term care program for the elderly and those with disabilities, and of insurance for children in low-income families. The TRICARE program provides health insurance for military dependents.

Public insurers differ from private insurers in several important ways. Like self-insured businesses, they do not have to contend with making a profit, nor do they need to maintain specific reserve levels or comply with state insurance regulations. For the most part, public insurance funds are financed by taxes rather than premiums, although premiums and co-pays both exist for Medicare beneficiaries. Use of taxation means that public insurers are not constrained by the same types of financial constraints as commercial carriers—especially with respect to the balance between a patient’s ability to pay for premiums and co-pays and the benefits provided.

However, the most important difference between public and private insurance is that public insurers have the full weight of the government behind them. In the case of Medicare and Medicaid, this includes the power of laws made by Congress, the prosecutorial clout of U.S. attorneys, and the investigative resources of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. These powers place public insurers in a completely different league from private companies—one that can easily work its will on patients and providers through the use of carrots, sticks, and actual intimidation. Put simply, if you cross a private commercial insurer, they can cancel policies and deny payments. If you cross a public insurer, they can assess enormous financial penalties and put you in jail.

Why is this so important?

Unlike private companies whose means and motives can be readily understood in economic terms, public insurers are not only economic entities, but also instruments of political policy. The challenge to patients and providers is that political goals are inherently unpredictable. Instead of being rationally based upon the provision of care or economic criteria, political aims can vary at the whim of individuals, political parties, or interested lobbyists. Because everyone else in the healthcare system has clear motives and business needs, an arbitrary approach on the part of government—the only player with the full force and power of the state behind it—can cause serious problems for others with respect to planning, operations, and economic viability. Indeed, as we’ll see shortly, government’s lack of a thoughtful, broad-minded and consistent approach to healthcare has caused a considerable amount of friction for patients, providers, healthcare facilities, and even commercial insurers for the past 50 years.

Garnering Revenue

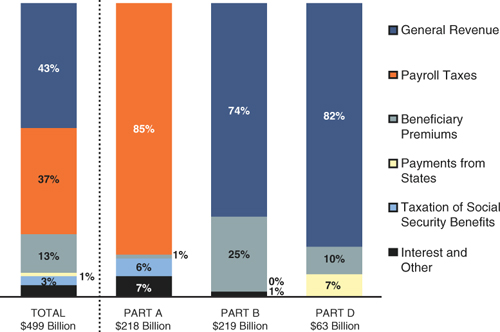

As with any insurer, public insurers need cash to provide benefits. In the case of Medicare and Medicaid, this cash comes from several different sources. As shown in Figure 6.5, Medicare is operated as several different programs, titled Parts A, B, C, and D.

• Part A pays for hospitalization expenses, including home health, which is partially funded under Part B.

• Part B pays for outpatient services, including physician visits, outpatient procedures, and durable medical equipment such as wheelchairs, oxygen tanks, and so on.

• Part C consists of the so-called “Medicare Advantage” plans, which is actually a program in which beneficiaries are enrolled in commercial insurance programs with Medicare basically paying the premiums. In this case, all benefits are provided by those third-party insurance programs.

• Part D is Medicare’s prescription drug benefit.

Figure 6.5. Estimated Sources of Medicare Revenue, 2010

From: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. “Medicare Fact Sheet—Medicare Spending and Financing.” August 2010.23

As you can see, the funding for each of these programs comes from a number of different sources and in different proportions. Medicaid funding is provided by a combination of state and federal taxation.

In practical terms, this means that the administrators who actually operate Medicare have little or no control over their sources of revenue. Changes in Medicare-related taxes must be made directly through Congress. Changes in premiums and patient co-pays are more flexible, but premiums account for no more than 12% of total Medicare revenue. This is clearly a problem. Increases in taxes and premiums are always politically unpopular—especially during times of economic recession. Because of this, the future of Medicare’s long-term solvency under its existing financial structure looks grim. Unless something is done to increase revenue or reduce expenses, current projections are that the Medicare Trust Fund will be exhausted by 2019.§§§

§§§ In reality, all the money earmarked for Medicare has already been spent. Medicare taxes are not held in some separate account, but are instead used to purchase U.S. government bonds. The cash is then used to pay for national defense, government salaries, overhead, and so on. Because the federal government is currently running fiscal deficits, there will be no surplus tax revenues available to buy back those bonds. The 2019 milestone simply marks the moment that the country has collectively spent more on Medicare than it has collected in taxes since the program began in 1965.

The net result is that Medicare and Medicaid administrators have little or no ability to manipulate revenue to balance their own budgets. The only tools that they have readily available are ways to minimize payouts.

Minimizing Expenditures

Public and private insurers have different constituencies and are operated by different types of people. Whereas private companies are accountable to shareholders and their executives are rated with respect to profitability, public insurers are accountable to politicians in legislatures and the executive branch. Public insurance managers are rated by two criteria: savings to taxpayers, and services delivered to patients and their families who vote.

This difference in perspective creates an important difference in the approaches taken by public and private insurers toward reducing claims-related expenditures. Private insurance executives see sick, expensive patients as a drag on earnings. If possible, eliminating those patients from the covered pool would reduce costs, increase shareholder value and maximize profits. Public insurance administrators have no choice but to retain any and all qualifying patients within their covered pool. As a result, their motivation must be to provide as much care as possible for constituents at the lowest possible cost. In real terms, this means that the savings must come from reducing payments to doctors, hospitals, and others who provide healthcare goods and services.

Minimizing Provider Outlays

Within the scope of limiting payments to providers, public insurers have different options than private carriers, partly as a result of their commitment to serving their constituents, and partly as a result of having the force of the government behind them. Unlike the case for private carriers, limiting access to providers is not an option for conventional Medicare. Medicare and Medicaid payments to providers are already so low that access to care for constituents is already a problem. There are no savings to be derived by steering patients to selected groups of providers under the conventional Medicare programs.

One option that public payers do have is to unilaterally reduce payments for healthcare services rendered to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. In fact, a provision to routinely and automatically reduce provider payments was built into the laws that fund Medicare in 1998. In a bizarre twist, these provider payment reductions have been rescinded by Congress each year since 2003. The rescissions have been necessary because Medicare and Medicaid payments are already so low that they threaten the financial viability of healthcare providers. If these cuts were to actually go through, large numbers of physicians would be forced to drop Medicare and Medicaid patients entirely.

Despite (or perhaps because of) perceived political limitations on overt rationing, governments can and do take advantage of covert rationing. Government efforts to covertly ration care have traditionally tended to rely on complexity and fear rather than manipulating or withholding provider payments.**** There are two main tools that are used in this regard: regulatory complexity and fear of being caught up in a “regulatory speed trap.”

**** Although this might be changing with the growth of so-called “pay-for-performance” programs.

Covert Rationing and Public Insurers24

Covert rationing efforts undertaken by private insurers are based upon efforts to align the financial and legal interests of physicians with those of insurance companies. In many cases, this places healthcare providers in a “no-win” situation. On one hand, the historical doctor-patient relationship dictates that a physician has the patient’s best interests in mind, first and foremost. On the other hand, financial and legal pressures applied by insurers are specifically designed to force doctors into placing the interests of carriers first.

The doctor-patient relationship is built on trust. It says that our doctors can be trusted to give us, as patients, the best possible advice with respect to what would be best for us as individuals and our own health. It should be obvious that asking doctors to consider the interests of insurers over the interests of patients poisons the doctor-patient relationship. However, this is exactly what covert rationing is designed to do.††††

†††† Overt rationing does not have this same destructive effect because all the information and considerations are out in the open. Whether the American people care about the doctor-patient relationship and wish to preserve it is beyond the scope of this book. Readers are referred to The Covert Rationing blog, The Road to Hellth blog, and others.

Public insurers’ covert rationing methods are somewhat different from those in the private sector. Instead of gag clauses, capitation, and sharing pools of leftover treatment money, governments covertly ration through three methods: regulatory complexity, unfunded mandates, and “standardization.”

Beginning with just a few public health measures in the 1900s, the number and complexity of the healthcare rules and regulations imposed on healthcare providers has now outgrown their ability to handle them. A wide range of state and federal rules suck up enormous amounts of provider time and overhead. As time is the only inventory clinicians have, more time spent on administration means that less time will be spent on providing services to patients. Less time with patients yields fewer services and lower total bills. The de facto result is a rationing of care.

Another side effect of healthcare’s regulatory complexity is fear—fear of inadvertently violating the enormous number of laws and regulations that no one can possibly keep up with and that even fewer can understand. Healthcare providers routinely fear being accused of fraud or some other form of criminality—a situation that Fogoros has labeled the “regulatory speed trap”:25

- Over a long period of time, regulators promulgate a confusing array of vague, disparate, poorly worded, obscure, and mutually incompatible rules, regulations, and guidelines.

- Individuals or companies, having to provide a service despite hard-to-interpret regulations, render their own interpretations (usually with assistance from attorneys, consultants, and the regulators themselves), and act according to those interpretations.

- By their apparent concurrence with (or at least by their failure to object to) the provider’s interpretation of the rules, over time regulators allow de facto standards of behavior to become established.

- After substantial time passes, regulators reinterpret (or “clarify”) the ambiguous regulations in such a way that the de facto standards now constitute grievous violations. They typically apply these clarifications retroactively.

- Regulators aggressively prosecute the newly felonious service providers.

Any practicing clinician can testify to the fear of running afoul of government rules and regulations in their everyday lives. This fear routinely leads to under-billing for services, avoiding patient discussions of therapies that might be experimental, not covered (or covered poorly) by Medicare, over-documentation, and a general sense of paranoia when it comes to clinical care interactions.

Another important difference between private and public institutions is the government’s ability to impose unfunded mandates. Unfunded mandates are requirements that healthcare providers provide additional services at the government’s behest, but at no charge to the government. One example is the mandate regarding the provision of language interpreters. In 2000, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services promulgated a rule requiring healthcare providers to provide translators for patients with limited English proficiency. The healthcare providers themselves were required to pay for the interpreter services, and neither the patient nor Medicare could be billed for the translation. This immediately led to many financially impossible situations, such as one physician having to pay $237 to an interpreter for a single patient visit. The physician’s own Medicaid reimbursement for the visit amounted to only $38.26

It’s not hard to imagine that this type of economic punishment would eventually force doctors to drop Medicare and Medicaid patients entirely. In 2002, physicians were forced to pay $156.9 million of the $267.6 million spent on medical interpreter services. Facing the prospect of having their constituents lose access to medical services entirely, in 2003 Medicare issued a “guideline” that largely dropped the interpreter provision requirement from Medicare Part B, but retained it for other areas of Medicare and Medicaid.

This type of mandate would be inconceivable for private insurers because physicians would refuse to bear expenses that—in some cases—were greater than their medical collections. In a short period of time, none of their covered patients would be seen by providers. In contrast, the government’s monopoly status, huge patient base, and the authority of state gives public insurers broad leeway. It is exceedingly easy for this power to create conditions that are expensive, economically unsustainable, and highly inefficient.

For its part, standardization is widely recognized to be one of the bases of modern industry and industrial production. In many applications, standardization has produced profound efficiencies. The standardization of weights and measures makes it simple and inexpensive to compare quantities and pricing. The standardization of computer communication brought by the Internet has reduced the cost and dramatically increased the speed and quality of shared information. It is only natural to think that the standardization of clinical care might produce enormous efficiencies in the provision of healthcare services. Some standardization has, and will have, many benefits to offer patients, providers, and the healthcare system as a whole. Like anything else, however, standardization can be taken too far.

To discuss the implications of standardization for healthcare, it is once again useful to refer to the observations of Dr. Fogoros. As he points out, “standardization is virtually a synonym for industry.”

In industry, standardization is the primary means of optimizing the two essential factors in any industrial process: quality and cost.

Let’s state this formally as the Axiom of Industry: The standardization of any industrial process will improve the outcome and reduce the cost of that process.

If you had a widget-making factory, you would break your manufacturing process down into discrete, reproducible, repeatable steps and then optimize the procedures and processes necessary to accomplish each step. To further improve the quality of your finished product (or to reduce the cost of producing it), you would re-examine the steps, one by one, seeking opportunities for improvement.... The beauty in such as system is that you only have to make one change—to the process itself—and every widget that comes off the line after you make that change will be improved.

The success of standardization in industry has spawned many efforts to introduce similar processes into medicine. One example is the use of “critical pathways,” in which specific medical problems are treated according to a standard set of practices. These are often used for medical procedures such as hip or knee replacement surgery, in which the nature of the problem is elective, the scope of care is limited, and the processes involved are often mechanical. Everything from the admissions process to discharge is precisely scripted, including the questions asked, the medications given, site preparation, the way in which procedures are performed and the timing of physical therapy. Problems that seem to recur are systematically addressed, regardless of whether they are due to human or technical factors. The net result is often a progressive improvement in medical outcomes, fewer complications, shorter hospital stays and lower costs.

To the casual observer, this all seems perfect. What could possibly go wrong with such a logical and measured approach? Shouldn’t all healthcare be standardized, and isn’t it appropriate that both public and private insurers and government agencies of all types rapidly enforce this approach for every circumstance?

Unfortunately, there are several important problems that limit the utility of standardization in healthcare—and can even transform it into a tool of covert rationing and remarkable inefficiency.

First, as Dr. Fogoros has explained, not all medical processes are suitable for standardization. “The standardization tools of managed care work only when you’re dealing with a process that can be broken down into a series of predictable tasks that generate reproducible results. In other words, industrial management tools work best when the process of care is similar to the process of making widgets.”

Certain medical procedures clearly meet the criteria for standardization. Elective surgeries for hip and knee replacement have clear causes and mechanical solutions that can be broken down into a series of discrete steps. These procedures can also be reserved for otherwise healthy people admitted under controlled conditions. All these factors serve to minimize expense and potential complications.

The problem is that the vast majority of problems that doctors confront each year don’t have these nice, neat characteristics. When a new patient presents to the hospital complaining of shortness of breath, there are dozens of possible causes and courses of action to be considered. These range from heart problems to lung problems; from anemia, to growths, or foreign objects physically obstructing the airways. Correctly diagnosing and managing the problem is a highly customized process in which no two patients are alike, and no standard approach is possible. Attempting to implement standardized approaches under these circumstances is highly complex, and often does far more harm than good. In the real world, “cookbook” medicine is rarely good medicine.

Second, standardization does not always improve outcomes and reduce costs. Why? Because patients are not widgets.

If you’re a widget maker, deciding between two manufacturing processes is a matter of economics. Nobody expects you to consider the widget itself. The outcome by which you are judged has nothing to do with how many individual widgets get discarded during the manufacturing process or even the quality of the widgets that pass final inspection. Instead, it’s the bottom line: how much profit do you make with relation to whatever level of quality you put into the widget. So the quality of the widget is not necessarily maximized, instead it’s optimized, tuned to the optimal quality/cost ratio as determined by the market forces of the day....

If instead of running a widget company you’re running an HMO, the calculus is different. You’re supposed to be more interested in how things turn out for individual patients than you are in the bottom line. So an expensive process that yields a better clinical outcome is one most people (patients, at least) would expect you to use, even though it only gets you a healthier patient and doesn’t make your money back for you. A process that increases patients’ mortality rate by five percent is one you should disregard, even if it is substantially cheaper than the alternative. The clinical outcomes experienced by patients—the measure of success you’re supposed to be concerned about—might move in the same direction as costs, or in the opposite direction.27

It’s easy to see that any public insurer is going to be torn between using standardization to minimize cost, and using it to maximize health benefits to constituents. One can’t do both.

The third problem with medical standardization by public agencies is a problem that anyone who has ever dealt with government will immediately appreciate: bureaucracy.

Some standards need to last forever. Civilized life requires that we all drive on the same side of the road, use uniform measures and adhere to the same laws. But as we have just seen, many standards that can be applied to healthcare—such as critical pathways, medical guidelines and even formularies—must be living, flexible and ever-changing. Medicine should be based upon science, and that science changes as our knowledge grows over time.

In contrast, standards set by government agencies are notoriously inflexible and slow to change. Even worse, rigid standardization historically tends to stifle innovation and improvement. Guidelines and other standards promulgated by public insurers have the force and power of the state behind them. Violations and variances are, almost by definition, punishable events; otherwise insurers have no way of enforcing desired behavior and discouraging behaviors they wish to avoid. Healthcare providers who wish to maintain their licenses, income, and good standing in their professional communities will instinctively tend to toe the official line no matter what circumstances might present themselves. Second, bureaucracies are themselves notoriously slow to change. Anxious to avoid mistakes, eschewing controversy and reluctant to do anything that might have unforeseeable effects on the cost of care, their standards tend to change at a snail’s pace, if at all.

A final problem presented by mandated standards is one of politics: Namely, whose standard do you use? “Dueling” healthcare standards in healthcare are becoming increasingly common as a direct result of the importance being attached to them. As the government begins to pick winners and losers by virtue of its mandates, medical lobbying has begun to twist and distort healthcare, just as it has twisted much of the rest of government policy. Different factions of the medical establishment are now pushing to have their own guidelines accepted as the last word in patient care.28 Who is better qualified to dictate the standard for the management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children: pediatricians or psychiatrists? Who should determine what heart studies should be done and how they should be interpreted in ADHD patients about to begin therapy: pediatricians or cardiologists?

In the context of our current discussion, we are most interested in efficiency and the runaway cost of healthcare. Guidelines of care, critical pathways, and other managed care tools are widely seen as ways to reduce costs and increase efficiency. How is it possible for overuse and over-reliance on standards by public insurers to actually damage the economic efficiency and effectiveness of our healthcare system?

The answer is that many “standards” in healthcare rapidly make the transition from being flexible guidelines to rigid rules, regulations, and mandates. The existence and proliferation of these rules directly affects the budgets and performance of providers and insurers alike, just as well-intentioned over-regulation can destroy the viability of small businesses of all types. Regulations that add to administrative overhead are inflating the cost of every single healthcare good and service provided in the United States today:

• Standardization measures don’t implement themselves. Every guideline, critical path, and formulary requires time and money to create, disseminate, learn, and implement. The more numerous and specific they are, the more time and money is required—often diverting time and resources away from other aspects of patient care.

• Guidelines need to be maintained. Outmoded guidelines not only waste time but money and lives, as better (and sometimes less expensive) methods of care are found. Each time a guideline is altered, each of the costs incurred by its creation, dissemination, education, and implementation is repeated.

• Standards reduce clinical flexibility, and can actually incur additional costs with little or no benefit to the vast majority of people they affect. Part of this is a result of creating guidelines or other standards that simply cannot be practically implemented in the clinical setting, no matter how logical and beneficial they might be in theory.

• Standards have ways of proliferating, often beyond those relatively “widget-like” applications for which they can be most useful. Proliferating standards can overwhelm providers and their support systems.

• Under many circumstances, standards grow to become mandates. These divert resources from other elective uses that might have a much higher return on investment to the patients involved. One example is a formulary that will pay for an older, well-established, but relatively ineffective drug that is part of a treatment “standard,” but not for a newer and more effective drug that would be more cost-effective in a given patient.

The bottom line is that public insurers and other government agencies covertly ration healthcare by underpaying for services and creating so much overhead and complexity that administrative overhead simply overwhelms the actual provision of expensive healthcare services. But is covert rationing on the part of government intentional? Is it plausible that regulators and administrators periodically get together to purposely reduce the efficiency of healthcare and intimidate doctors into turning away patients with the riskiest conditions?

It simply doesn’t matter. The ultimate impact of these government initiatives is to reduce the amount of time and energy that clinicians can devote to providing actual healthcare services. Whether this occurs as the result of clever forethought or with absolutely no forethought at all, the end result is the same. The only way to stop this type of covert rationing and its adverse economic impact is to rethink any and all government healthcare regulations and limit the ways in which they are used and/or abused.

Government